| Battle of the Narrow Seas | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585) & the Eighty Years' War | |||||||

The Battle in the Strait Between Calais and Dover on 3 and 4 October 1602 Between the Spanish Galleys of Federico Spinola and Dutch and English Warships Painting by Andries van Eertvelt | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

6 galleys

| 9 galleons, carracks, & galiots | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2 galleys sunk, 1 galley burnt, crew interned 2,000 killed, wounded, or captured[5] | Light | ||||||

The Battle of the Narrow Seas, also known as the Battle of the Goodwin Sands or Battle of the Dover Straits was a naval engagement that took place on 3–4 October 1602 during the Anglo-Spanish War of 1585 and part of the Dutch Revolt. An English fleet under Sir Robert Mansell intercepted and attacked six Spanish galleys under the command of Federico Spinola in the Dover Straits. The battle was fought initially off the coast of England and finally off the Spanish Netherlands. The English were soon joined by a Dutch fleet under Jan Adriaanszoon Cant, and they completed the destruction.[6][7]

Background

In 1602 Frederico Spinola, younger brother of Ambrogio Spinola, had distinguished himself greatly as a soldier in the Army of Flanders and had succeeded in 1599 going through the English Channel and passing the straits of Dover unmolested; this led to a panic called the invisible armada, as it encouraged suspicions that the attempt might be renewed and on a larger scale.[8] Buoyed by this achievement, he had indulged Philip III of Spain, the Duke of Lerma and Martín de Padilla, in a vision of a massive galley-borne invasion of England from Flanders. However, the council brought him down to a mere eight galleys, provided at Spinola's expense.[1] He was on his way from San Lucar to Lisbon but he was defeated by Sir Richard Leveson at Sesimbra Bay, which cost him two galleys.[4]

After this defeat Spinola took his remaining six galleys back to Lisbon and filled his vessels with pay chests for Flanders. During the sailing to Flanders he captured an English merchant ship, which he left at A Coruña.[9] At Santander he took on a further 400 troops to complete the tercio complement of 1,600 men. In England word had spread that Spinola was on his way in an attempt to run the English Channel again. The heading of the six galleys was for Sluis. Robert Cecil was well informed of their approach, even already when they arrived at Blavet, in Brittany, at the beginning of October.[10][11]: 386–387 Queen Elizabeth decided to act, so she appointed Sir Robert Mansell to join with a States fleet before Dunkirk and Sluis, to see what they could do to impede them.[12] Meanwhile, the States of Holland and West Frisia had sent a flotilla of nine ships under Vice-Admiral Jacob van Duyvenvoorde to intercept Spinola, but when this force arrived near Spain, Spinola had already escaped to the north. Van Duyvenvoorde, coping with an outbreak of smallpox by which he was himself afflicted, sent four of his ships back north under Jan Adriaanszoon Cant, known by the English as Jan van Cant.[13]

Engagement

Mansell, with three ships (the 30-gun Hope along with the 42-gun Victory and the Answer), departed and patrolled about Dungeness. Mansell's flag captain came up with the strategy on how to tackle Spinola; he predicted that Spinola would try to sail close to the English coast. Acting on this hunch, Mansell set each ship a good distance from the next using flyboats so that a good communication system was erected between themselves and the Dutch fleet off the Flemish coast under acting Vice-Admiral Jan Cant.[4] On the 3rd, Mansell was soon joined by two Dutch flyboats, Samson and the Moon to improve communication, and now Spinola was effectively sailing into a trap.[11]: 388

Action with the English

In the moonlight of 3 October, just before midnight, Mansell was on the lookout for Spinola's galleys, which were soon sighted. Mansell ordered an attack, and off Dungeness Moon, Samson, and the Answer charged at the galleys.[6][10] Spinola, seeing this, decided to swing his galleys round to face to the southeast, the direction of the Flanders coast, but in so doing the lead ship, San Felipe (St. Philip), ran straight into the Victory and Hope, forcing the galleys inadvertently further east.[10]

Sources differ on what happened when the Spanish galleys came under fire from the English ships: the English side asserted that the San Felipe was nearly battered into submission by Victory's guns and that she was able to escape only when the other galleys came up in support, drawing Victory's and Hope's fire.[11]: 392 In contrast, the Spanish have claimed that Spinola's galleys succeeded in passing almost unscathed between the English ships by rowing at full strength.[14] Mansell decided on creating as much damage as possible; instead of concentrating on one galley, he ordered his gunners to blaze away at anything they saw in the moonlight and as a result he believed that damage was inflicted on most of the galleys.[15] A number of galley slaves leapt into the sea from the damaged ships – a few even made it to shore where they were captured and interrogated at Dover Castle.[16] By the time both fleets reached Goodwin Sands the Spanish galleys started to retreat in desperation for the Flemish coast.[10] A gale was now blowing strongly from the west which favoured the pursuing English ships and soon the gunfire was a signal for the Dutch to engage.[6]

Dutch join the attack

The action continued across the Narrow Seas towards Dunkirk, Nieuwpoort, Gravelines, and Sluis.[7] The Dutch Admiral Jan Cant soon cut off the Spanish and the English waited outside of the Flemish road stead in case any tried to escape elsewhere. The States' ship Makreel came in sight and attacked the already damaged San Felipe, pouring in a broadside. Drawing off from this assailant, the galley found herself close to Vice-Admiral Cant's Halve Maene. The galley tried to evade discovery by remaining immobile in the darkness but this had disastrous results. The Halve Maene bore straight down upon the galley and struck at her amidships carrying off her mainmast and her poop.[5] Whilst extricating itself with difficulty from the wreck, Halve Maene sent a tremendous volley of cannon fire straight into the waist. Another State's galliot bore down to complete the work; San Felipe sank quickly, carrying with her all the galley slaves, sailors, and soldiers.[4][5]

The Lucera, trying the same evasive tactic, was the next galley attacked; a Dutch galiot, which drove under full sail, managed to ram her. The galley was struck between the mainmast and stern, with a blow which carried away the assailant's own bowsprit, but in return completely demolished the stern of the galley. Vice-Admiral Cant came up once more in the Halve Maene and finished Lucera (Morning Star) off by ramming, tearing the galley apart.[5] Meanwhile, Victory and two States' galiots were chasing two galleys: San Juan and Jacinto, which were already in a sinking state. With nowhere to escape and the gale blowing against them, the only option was for the commanders to run them aground near Nieuwpoort. In the end, both galleys succeeded in reaching the safety of this port.[14] Another galley managed to evade the Dutch and English long enough but it too ended up being wrecked on the French coast near Calais.[11]: 393 The galley San Luis, which bore Spinola himself and his thirty-six pay chests, attempted to reach Dunkirk, but as the tide was low, she was forced to wait beyond a sandbank. Ten Dutch ships fell upon San Luis, but Spinola succeeded in sailing between the Dutch vessels and reached Dunkirk.[14] With this the battle had ended and a Dutch blockade formed to prevent Spinola's escape.[1][11]: 395

Dutch Ships Ramming Spanish Galleys off the Flemish Coast in October 1602, Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom

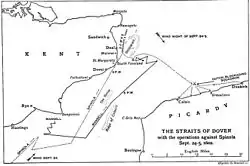

Dutch Ships Ramming Spanish Galleys off the Flemish Coast in October 1602, Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom Map of the battle

Map of the battle

Aftermath

Casualties were exceptionally heavy for the Spanish; as two galleys sank with all hands, with perhaps over 2,000 killed, wounded, or captured. At Calais the wrecked galley was chopped up and used as firewood by the French, the Spanish crew were interned and the galley slaves freed.[10] Casualties for the Dutch and English were light with some ships suffering no casualties at all. Two Dutch ships were damaged in the ramming that took place but the rest of the Dutch ships suffered only minor damage.[5] The English ships suffered no damage at all except for a broken mast on Samson due to the gale.[5] The battle clearly showed the difference between galleons and galleys, in particular the uselessness of a Mediterranean-type galley in northern waters.[15] The transition in warfare, along with the introduction of much cheaper cast iron guns in the 1580s, proved the "death knell" for the war galley as a significant military vessel.[11]: 395 [17]

Mansell was rewarded for his part in the victory and was named Vice-Admiral of the Narrow Seas in commemoration of the name of the battle.[6] Van Duyvenvoorde and Cant both received honorary golden chains from the States of Holland. As for Spinola, he managed to save half of the galleys, as the two which had reached Nieuwpoort were soon able to join San Luis in Dunkirk.[14][18] From there, the three ships sailed unmolested to Sluis, where Spinola with his five galleys still represented a threat to the English and Dutch shipping.[9][14] Both the English and the Dutch were gradually able to gain supremacy in the seas not just in and around the English Channel but in all the European waters.[1] As a result, Spinola would be defeated again and mortally wounded at the Battle of Sluis by the blockading Dutch forces in an attempt to escape.[4][11]: 395 Spinola's death and the subsequent surrender of Sluis to the Dutch in 1604 ended his and Philip III's dreams, and English fears, of a galley-borne invasion of England from Flanders.[1]

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wernham pp. 400–401

- ↑ Graham p. 270

- ↑ Wernham, English and Dutch Fleets Commanding the Seas Both off the Spanish Coast and the Narrow Seas, p. 401.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gray, Randal (1978). "Spinola's Galleys in the Narrow Seas 1599–1603". The Mariner's Mirror. 64 (1): 79–81. doi:10.1080/00253359.1978.10659067.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Motley pp. 114–116

- 1 2 3 4 . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- 1 2 Jaques p. 714

- ↑ Wernham pp. 269–72

- 1 2 Fernández Duro, Cesáreo: El Gran Duque de Osuna y su marina: jornadas contra turcos y venecianos. Spain: Renacimiento, 2006. ISBN 84-8472-126-4, p. 296

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bicheno pp. 298–99

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Corbett pp. 386–95

- ↑ Lemon, Robert (1870). Calendar of State Papers: Preserved in the State Paper Department of Her Majesty's Public Record Office. Reign of Elizabeth: 1601–1603. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 243.

- ↑ J. P. Sigmond, 2013, Zeemacht in Holland en Zeeland in de zestiende eeuw, Hilversum, Verloren, pp. 301–303

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rodríguez Villa, Antonio: Ambrosio Spínola, Primer Marqués de los balbases. Madrid: Estab. tip. de Fortanet, 1905, pp. 36–37

- 1 2 Archibald, Edward H. H. (1968). The wooden fighting ship in the Royal Navy, A.D. 897–1860. Blandford P. pp. 17 & 96. ISBN 9780713704921.

- ↑ "Sir Thomas Mansell routing of 6 Spanish galleys. 1602". Margaret's History Catalogue. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ↑ Guilmartin p. 254

- ↑ Fernández Duro, Cesáreo: Armada española desde la unión de los reinos de Castilla y de Aragón. Vol. III. Instituto de Historia y Cultura Naval, p. 222

Bibliography

- Bicheno, Hugh. (2012). Elizabeth's Sea Dogs: How England's Mariners Became the Scourge of the Seas. Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-174-3.

- Corbett, Julian Stafford (2012). The Successors of Drake. HardPress. ISBN 9781290266758.

- Graham, Winston (1976). The Spanish Armadas. Fontana. ISBN 978-0-88029-168-2.

- Guilmartin, John Francis (2002). Galleons and Galleys. Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35263-0.

- Jaques, Tony (2006). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8500 Battles from Antiquity Through the Twenty-first Century. Vol. 2. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33536-5.

- Motley, John Lothrop. History of the United Netherlands from the Death of William the Silent to the Twelve Year's Truce, 1602–03. pp. 114–16.

- Wernham, R.B. (1994). The Return of the Armadas: The Last Years of the Elizabethan Wars Against Spain 1595–1603. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820443-5.

External links

- Debasing Shakespeare – An exercise in logic, open-mindedness, and Shakespeare – Federigo Spinola

- "BATTLE OF THE GOODWIN SANDS 1602". Historic England. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016.