| Siege of Ostend | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War & the Anglo–Spanish War | |||||||||

Siege of Ostend by Peter Snayers, oil on canvas. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

2,500–8,000 (peak) Total: ~50,000 (by rotation)[Note B] |

9,000–20,000 (peak) Total: ~80,000 (by rotation)[1] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

30,000[2] – 45,000[3] killed, wounded or succumbed to disease 3,000 surrendered[4][5] | 60,000[2] – 70,000[6][7] killed, wounded or succumbed to disease | ||||||||

The siege of Ostend was a three-year siege of the city of Ostend during the Eighty Years' War and the Anglo–Spanish War. A Spanish force under Archduke Albrecht besieged the fortress being held initially by a Dutch force which was reinforced by English troops under Francis Vere, who became the town's governor.[8] It was said "the Spanish assailed the unassailable; the Dutch defended the indefensible."[9][10] The commitment of both sides in the dispute over the only Dutch-ruled area in the province of Flanders, made the campaign continue for more than any other during the war. This resulted in one of the longest and bloodiest sieges in world history: more than 100,000 people were killed, wounded, or succumbed to disease during the siege.[3]

Ostend was resupplied via the sea and as a result held out for three years.[11] A garrison did a tour of duty before being replaced by fresh troops, normally 3,000 at a time keeping casualties and disease to a minimum.[12] The siege consisted of a number of assaults by the Spanish, including a massive unsuccessful assault by 10,000 Spanish infantry in January 1602 when governed by Vere.[13] After suffering heavy losses, the Spanish replaced the Archduke with Ambrosio Spinola and the siege settled down to one of attrition with the strong points gradually being taken one at a time.[4]

Ostend was eventually captured by the Spanish on 20 September 1604 but the city was completely destroyed and the overall strategy had changed since the siege had started.[4][14] The loss of Ostend was a severe blow strategically for the Republic but Spanish propaganda and strategic objectives were frustrated by the Dutch and English conquest of Sluis to the northeast a few weeks before the surrender of Ostend.[15][16] In addition, the economic cost of such a long campaign and the enormous number of casualties sustained turned the result into a Spanish pyrrhic victory[17][18] and effectively the siege contributed largely to Spanish bankruptcy three years later which was followed by the Twelve Years' Truce.[19][20]

Background

In 1568, during the reign of Philip II of Spain, the Netherlands, until then under the rule of the Spanish Empire, took up arms against the Spanish crown.[21] The first phase of the war began with two unsuccessful invasions of the provinces by mercenary armies under Prince William I of Orange (1568 and 1572) and foreign-based raids by the Geuzen or Sea Beggars, (irregular Dutch land and sea forces).[22] By the end of 1573 the Beggars had captured the bulk of the provinces of Holland and Zeeland as well as converted the populace to Calvinism, and secured against Spanish attack. The other provinces joined in the revolt in 1576, and a general union was formed.[23]

In 1579 the union was fatally weakened by the defection of the Roman Catholic Walloon provinces in the Union of Arras.[24] By 1588 the Spanish, under Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, had reconquered the southern Low Countries leaving only Ostend as a major rebel enclave along the coast and stood poised for a death blow against the nascent Dutch Republic in the north.[25] Spain's concurrent enterprises against England and France at this time, however, allowed the Republic to begin a highly successful counter-offensive under Maurice of Orange which lasted from 1590–1600, known as the Ten Glory Years.[26][27]

In 1599 the Archduke Albert of Austria and Isabel Clara Eugenia, brother and sister of Philip III, ruled as joint sovereigns of the Netherlands through the will of the dying Philip II.[28] By 1600 Maurice of Nassau was stadtholder and Johan van Oldenbarnevelt was Grand pensionary of the States General of the Netherlands.[11]

In 1601, Spain, now under King Philip III with his favourite the Duke of Lerma, despite maintaining its hegemony in the world, was economically weakened with war and bankruptcy.[29] Starting with the bankruptcy of the Royal Treasury in 1575; operations against the Ottomans in the Mediterranean, thirty years of war in Flanders against the rebel forces of the United Provinces and a war with England which had waged from 1585.[7] Spain had also only just finished a costly and unsuccessful war with France.[24] The wars were a great burden for the Spanish Empire and meant that financially Spain depended entirely on the treasure fleet brought from the colonies.[7] Nevertheless, Philip pursued a highly aggressive set of policies, aiming to deliver a 'great victory' against both Holland and England.[30] The situation of the United Provinces was similar; more than thirty years of war, and foreign trade blocked by Spain had caused a financial drain. The Dutch tried to relieve their precarious finances by commercially expanding into the East Indies with the birth of the Dutch East India Company (VOC).[31] England was in the same position and was fighting now in Ireland.[24] Like the Dutch they too had just set up their own East India Company.[31]

In 1600 the Dutch and English Army under the command of Maurice of Nassau and Francis Vere respectively used Ostend as a base to invade Flanders, in an attempt to conquer the city of Dunkirk after their victory in the Battle of Nieuwpoort.[32] This never happened however as disputes in the Dutch command meant that taking Spanish-occupied cities in the rest of the Netherlands took over priority as the opportunity arose.[33] Maurice concurred and had his forces evacuated by sea leaving Ostend to be preoccupied by the Spanish.[12]

Ostend

Founded five hundred years earlier, the city of Ostend (translated into English meaning East – End) in the mid-16th century was a fishing village of about 3,000 inhabitants.[11] Ostend's strategic position in the province of West Flanders, along the North Sea and accessible to Dutch sea power, was fortified by the Dutch and English between 1583 and 1590, and turned into a major military port.[34] In the view of the State of Flanders; Ostend in the hands of the Protestant Dutch and English was a huge thorn in their side.[35] Ostend unlike other places in the Netherlands had never been taken by the Spanish and the garrison had even repelled an attack by Parma in 1583.[33] In 1587, during preparations for the invasion of England by the Spanish Armada, Parma had rejected the idea of a conquest of Ostend by considering it a reckless enterprise after the capture of Sluis.[36] The garrison had also made frequent incursions into the adjacent country.[33] Ostend was the only possession of the Dutch Republic in Flanders and its capture was of strategic importance for the Spanish.[24]

Defenses

The reason why Parma was so cautious to attack was not just for its defences, but also its place right near the sea.[12][37] The old church and town faced the seas, but in 1583 the new town, further inland, was fortified with ramparts, counterscarps, and two broad ditches.[24] The dunes were cut away, and the sea was allowed to fill the ditches and surround the town.[14] A canal called the Geule had begun to form a new harbour on the east side; it was wide, deep, and navigable and served the maritime traffic to the city.[11] To the south a framework of often flooded streams and wetlands would have made the area difficult to place heavy siege guns.[12] Where the land rose slightly towards the dunes, on either side of the town; the besiegers would be able to approach with their parallels and batteries and as such were vulnerable points.[37]

On the West side of Ostend another canal, the Old Haven, was more of a defensive moat which was barely navigable but could not be easily waded except for four hours at low tide.[37] A ditch passed between the old and new towns, which were connected by bridges, and round the new town, parallel to the Geule on one side, and to the old harbour and Yperlet stream on the other.[14] The Guele itself had ramparts and bulwarks on one side, and a counter scarp with ravelins on the other, while the water level for both canals could be adjusted from the lock located in the city.[12]

In the old town, closer to the mouth of the old harbour, a fort called the Sandhill had been constructed. The old town was protected by strong palisades forming bastions with connecting curtains, and a succession of three small forts; the Schottenburgh (next to the Sand-hill), the Moses Table, and the Flamenburg all defending a cut from the town ditch into the Geule, at the eastern corner.[12] On the eastern side of the town facing the Geule, the defences consisted of a range of bulwarks (or bastions) North Bulwark, East Bulwark or Pekell, Spanish Bulwark at the southeast angle, with an outwork called the Spanish Half-moon.[35] To the South and West an extensive outwork, the Polder, which had formerly been a field from which the water had been pumped by means of windmills near the point where the Yperlet stream flowed into the old harbour.[14] Flanking the Polder at both points were the South bulwark and the West bulwark, in front of each were two further outworks; the inner stronger Polder, South and West Bulwark's which then linked the Polder, South and West Ravelins. This then linked to the Polder, South and West square's; Ostend's most outer defensive works.[14]

At the northwest angle, near the mouth of the fordable old harbour, the walls consisted of a strong ravelin in the counter scarp called the Porcepic, and a bastion in its rear known by the name of the Helmund.[14][38] This was considered the most important area to defend as an attempt on the walls could be made on firm ground.[11][12]

The north area was open to the sea, where Ostend could receive reinforcements and supplies during the high tide.[35][36]

Forces

Armies during this period of warfare utilized pikes, arquebuses, swords, daggers, rudimentary (and unpredictable) explosives; early forms of hand grenades as well as artillery.[37] As there were more wounded than deaths in battle, amputations were the common solution for treating wounds. At this time poor sanitation spread infections and fever, causing more deaths than combat itself.[37]

The tercios, the regiments of the Spanish army, were regarded at the time as the elite of the military corps, and were key to Spain's European hegemony in the 16th century and the first half of the seventeenth century, and are seen by historians as a major development of early modern combined arms warfare.[38] The quality of their organization and strict discipline made them efficient but certain circumstances such as long delays in pay sometimes escalated into violent mutinies.[39] The tercios consisted of recruited soldiers of all domains of the Spanish Habsburg empire; Spaniards, Portuguese, Italians, Germans, Walloons, Swiss, Burgundians loyal to Spain, and dissident Catholic Irish, along with mercenaries from other countries.[40] They were led by the Archduke Albrecht who was military commander of the Spanish forces in the Low Countries.[7]

The defending forces of Ostend were the army of the United Provinces, reorganized by Maurice of Nassau who also played a part in the development of early modern warfare. The Dutch had large support from their Protestant ally England whose pike men and arquebusiers were clad in red cassocks (amongst the earliest English redcoats).[41][42] The English, having distinguished themselves highly in battles such as Turnhout and Nieupoort where they had faced and beaten the Spanish tercios, were considered the veterans, and the elite of the army as a whole.[14][43] They did have a reputation however as being thieves, pillaging friend and foe alike during and after battle.[38] Other Protestant troops from Scotland, France, and Germany took their side amongst Maurice's army.[35]

Siege

On 5 July 1601, the Archduke Albert opened the siege of Ostend with 12,000 men and 50 siege-guns in position; while the small garrison of under 2,000 was commanded by Governor Charles van der Noot.[14] The States General held that the defence of this outlying post was a matter of vital importance.[44] With this in mind they looked round for the ablest commander in their service.[45] Sir Francis Vere, the hero of Nieuwpoort, was chosen not as governor, but as general of the army along with ample powers.[33]

The Spanish besiegers soon rose to 20,000, a number which was one of the Archduke's preliminary objectives.[45] As the Spanish cannonaded the city, some soldiers tried to wade the moat but this failed and a number drowned.[44] The Count of Bucquoy, commanding forces east of Ostend, had been unable to do the same due over Geule, and began the construction of a dike from the sea up to the city; artillery was placed with which to fire at the boats coming and going from the North.[14] These works were constantly interrupted by the rising sea, evolving under fire from the city and in addition the superiority of the Dutch and English at sea.[35] In addition, the failure of the Spanish closing the north side of Ostend enabled it to receive reinforcements and supplies.[11]

Vere first proceeded to England to obtain the approval of Queen Elizabeth, and to raise a body of recruits – these were subsequently raised in East Anglia while some were pressed into service in London.[46] Vere's brother Horace was detached from Maurice's army with eight English companies to reinforce the Ostend garrison.[14][32]

Arrival of Vere

On 9 July, Sir Francis landed with these troops on the sands opposite Ostend.[47] Van der Noot met him at the water's edge, and delivered up the keys of Ostend.[37] The garrison then consisted of thirty companies of Netherlanders in two regiments of 2,600 men to which Vere added his eight companies of 100 men each, which brought up the total to 3,500 men.[14] Another 1,500 English troops under Edward Cecil arrived on 23 July to build up the garrison.[42]

On 27 July English troops led by Edward Cecil made a sortie and gained a large segment of trenches from the Spanish whom they put to flight; pursuing them to the sand hills with support from the town's artillery.[42] Casualties inflicted were heavy; around 600 including many prisoners. Amongst the killed was Don Diego Idiaquez, son of a former secretary of state to Philip II.[42]

On 4 August the Spaniards kept up a tremendous fire on the town from all their batteries, and Sir Francis Vere was severely wounded in the head.[47] Vere went to Middelburg to be treated for his wound, and in a few weeks he was convalescent.[44] In September he returned to Ostend along with more recruits from Holland, England, and Scotland.[48]

Meanwhile, the fire from the besiegers continued and the soldiers of the garrison dug underground quarters in the marketplace near the "Pekel" bastion, for protection against the hail of shot.[33][49]

The States General at this time demanded that Maurice should march to relieve the city; to take on the besiegers.[45] Vere was himself frustrated at both the lack of Dutch response from the States General and from Maurice; particularly when a few veteran companies including Edward Cecil's, were taken out of Ostend to join Maurice's forces back in the field.[42][50]

Maurice however knowing the futility in making a direct attack, chose to campaign in the surrounding areas in an attempt to block the Spanish supplies and divert the attention of the besiegers.[51] He laid siege to and retook Rheinberg and then continued to Spanish-held Meurs in August which was also captured.[45] Maurice hoped to take 's-Hertogenbosch but plans for the siege were cancelled and so withdrew to winter quarters.[49]

The spy

Albert had taken on a traitor; a Catholic Englishman by the name of Conisby, who went to England and then procured letters to Vere before he crossed over to Ostend.[52] He began to convey intelligence to the besiegers under an agreement with Albert.[53] A boat was sunk in the mud, on the banks of the Old haven, near the South square; Conisby was to deposit letters there from which a Spanish soldier then took them during the night. Conisby however grew bolder, and tried to bribe a sergeant to blow up the powder magazine.[54] The sergeant revealed the plot and Conisby confessed to everything, and was sentenced to be publicly executed but in an act of clemency was whipped out of the town.[52][55]

Assault on the Sandhill & South Bulwark

In December 1601 the number of defenders of the garrison was down to less than 3,000 but the besiegers suffered terribly and had only 8,000 men fit for duty out of 25,000.[56]

For the first six months and generally throughout the siege there were fired on average a thousand shots a day.[57] It was not until the end of November that the Spaniards had been at work advancing their batteries, forming foundations in the haven by sinking huge baskets of wicker-work filled with sand, and building floating platforms, on which guns were mounted in the "Geule".[58]

On 4 December a breach was made in between the Porcespic and the Helmund and the Archduke was prepared to storm.[56]

Vere made sure it was heavily guarded and placed Sir John Ogle's company there but was awoken by the alarm and rushed to the ramparts to discover the Spanish were assaulting the breach.[58] A force of 3 – 4,000 Spanish attempted to storm the position; the phalanx of Spanish pikemen managed to gain the breach but were forced out by a counterattack.[47] The Spanish then launched further attacks but were repelled again.[56] A fierce struggle ensued, and the besiegers were driven back while Vere ordered wisps of straw to be set alight and fixed on the ends of the pikes, so that the retreating Spaniards might be fired upon with effect as they fell back.[59] The assault never made it past the breach as the Spanish found the rubble almost impossible to fight on and suffered heavy casualties.[56] In the end the attack was a disaster and after half an hour the Spanish had lost over 500 men, nearly a quarter of the attacking force.[57][58]

Parley stratagem

The position in Ostend by the turn of winter was perilous; after nearly five and a half months siege and after two months without reinforcements.[50] Furthermore, the outer works such as the Polder had to be temporarily abandoned because of storms and exposed icy conditions.[60]

On 23 December, Vere learned from a deserter that the Spanish were in preparation for a large impending assault on the city; he realized he had no hope except to hold for time.[58] Vere's frustration with the Dutch continued, writing many letters and complaining about the lack of support, in addition he demanded reinforcements.[50] He therefore proposed a parley to the Spaniards for negotiations; but this was a ploy hoping to gain time to await the arrival of the reinforcements.[47][58] The Spanish accepted and Vere sent two of his captains, John Ogle and Charles Fairfax, as hostages to the Spanish camp, while the Spanish sent in return Mateo Antonio, quartermaster general of the Spanish army, and Matteo Serrano, Governor of Sluis, to negotiate terms of possible surrender.[58][61]

Vere then construed as much time as possible frustrating Spanish 'negotiations'; he ordered his men to beat to quarters even though there was no attack.[58][60] Vere then expressed anger at Serrano and Antonio as to why the Spanish had intended to attack and then refused to speak with them.[62] Vere then ordered them to stay put because of the dark and high tide, and flagons of English ale were given as compensation.[58] The next day they arrived back at Albert's headquarters; but he immediately sent them back.[61] While all this was going on vital repair work was carried out on the defences.[50]

Negotiations had been held off for twenty-four hours and Vere stated that the incident was a total misunderstanding and apologized.[62] Vere told Serrano and Antonio that the archduke must withdraw from Ostend or surrender his forces; the reply was the Archduke was to see the surrender of the town.[56] Vere then broke off the discussions again and both were invited to a banquet as it was Christmas Eve which they accepted with more time wasted.[59]

Rumours began to circulate outside that Ostend had fallen and the Archduke and Isabella had dressed in their best to await the surrender.[62] In the town however both Serano and Antonio were about to resume talks but during the night three ships arrived with 600 Zeelanders as reinforcements.[56] Vere's plan had worked, after which, he immediately broke off all negotiations.[50] The Spanish, in particular the archduke, were outraged; reluctantly they released Ogle and Fairfax once Serrano and Antonio had returned.[61] Albert refused to see any of his generals for several days blaming them for recommending to call off the assault and allowing the negotiations to go ahead.[62]

1602

.jpg.webp)

In early January two of the besieging batteries, consisting of eighteen cannon, sent balls of forty to forty-six pounds weight, which kept up a crushing fire on the Porcespic, Helmund and Sandhill.[63] The Spaniards had by that time sent 163,200 shot into the town, and scarcely a whole house was left standing.[64] Several houses, which had been ruined by the cannon fire, were pulled down for the sake of the beams and spars to be used as palisades.[65]

Great Spanish Assault

Vere soon after received intelligence from deserters and scouts that the Spanish were preparing for a general assault; and began to prepare for it.[66]

Preparations

At high tide, Vere shut the west sluice, which let the water into the town ditch from the Old haven in the rear of "Helmund", in order to retain as much water as possible.[67] Horace Vere and Charles Fairfax, with 12 companies armed with pikes and muskets, were stationed in the "Sand-hill".[68] Vere took his stand with six of his veteran English and Scots companies close by.[65] Two more companies, one English and one Dutch, occupied the Schottenburgh redoubt and from there to the destroyed church were 300 Zeelanders who had arrived on the 26th.[67] Ten Dutch companies occupied positions from the church, "Moses Table", North ravelin, and "Flamenburgh", while four large guns protected the harbour and the old town.[63]

The two most important works, flanking the breach, the "Porcespic" and the "Helmund", held ten Dutch and English companies along with nine guns loaded with grape shot.[64][66] In the "West Bulwark" two demi-culverins were placed to sweep the old haven.[63] Along the curtain of the old town, and on the breach which had been made under the "Sandhill", stones and bricks from the ruins of the old church, hoops bound with squibs, fireworks, ropes of pitch, and hand-grenades were ready to be poured on the attackers.[65][66]

By the evening the Spanish army had marshalled for a huge assault and were seen bringing down scaling ladders and ammunition.[66] Count Farnese, with 2,000 Spanish and Italian troops, were ordered to attack the "Sandhill" and the curtain of the old town wall.[67] The governor of Dixmunde, with 2,000 Spaniards, was to assault "Helmund" and the Porcespic; a force of 500 men was to scale the west ravelin, while a similar number attacked the "South Square".[66] On the east side Count Bucquoy was to deliver an assault, specially attacking the east ravelin and the defences of the new haven; in all the assault totalled some 10,000 men.[63]

Assault

Vere ordered his engineers to get on the breach to rapidly throw up a small breastwork, driving in palisades.[63] The Archduke fired a gun as a signal to Bucquoy, and the besiegers rushed to the assault from all points just as the darkness of night set in.[59] Vere's engineers immediately discovered Count Farnese wading across with his 2,000 Italians, and drawing them up in battalions on the Ostend side.[68][69] Vere then went to the top of the "Sandhill" and issued orders to have everything in readiness, but not to fire until he gave the signal, and then to open with both ordnance and small shot.[67]

As the Spanish approached ever closer Vere at once ordered a heavy fire on to the Spanish battalions heading towards the foot of the "Sandhill".[70] Along the curtain of the old town, the Spaniards rushed into the breach but as they climbed up they were met by ordnance fire from the bulwarks. Burning ash, stones, and rubble were hurled at them, before the flaming hoops were cast.[69][71] The Spanish no sooner climbed to the crest of the "Sandhill" and the "Schottenburgh" but were repelled three times with heavy losses after rallying to the charge, while the struggle on the breach continued during the space of an hour.[59][65]

Similar assaults were made on the Western ravelin, and on the "South Square", while on the east side three strong battalions of the Spanish were formed on the margin of the "Geule".[69] They then attacked the "Spanish Half-moon" outwork which was taken after heavy fighting.[61] Vere ordered its recovery and heavy fire was opened from the bulwarks and then an English company drove them out with a loss of 300 men, mostly captured.[70]

By midnight the Spanish were repulsed at all points having suffered heavily in the assault[59] and were milling about in the ford in confusion.[71] Vere saw an opportunity he could not miss, and ordered the west sluice to be opened, through which the waters that had been stored in the town ditch and had been closed at high tide now rushed down the haven in a huge torrent while the Spanish were wading across.[69] The damage inflicted by this torrent was tremendous and carried many of the assailants away into the sea.[61]

Once the waters had subsided the defenders then launched a counterattack, poured over the walls and secured an immense amount of plunder.[70] The Spanish retreated in complete disorder throwing away everything they had. The English were first into the fray; Spanish pistols, priest's cassocks, swords, gold chains, pendants, and enamelled shields were all taken from the dead and dying.[70] There were heaps of Spanish and Italian dead under the "Sandhill" and along the wall of the old town, amidst broken siege equipment.[65] Among the dead and wounded was the discovery of a young Spanish girl in male attire, who had fallen in the assault and under her dress was a chain of gold set with precious stones, along with other jewels and silver.[64][69]

Aftermath

Casualties from the assault were enormous; between 1,500 and 2,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, drowned, or captured,[71] which at the time represented at least a quarter of the whole besieging army.[69] Many noblemen, chiefs, and commanders were killed or missing; the extremely wealthy Italian Count d'Imbero was slain by an English private soldier of Fairfax's company; so too was Don Durango Maistro del Campo, also known as Colonel Don Alvarez Suarez (Knight of the Order of Santiago), the hostage during the parley Colonel Simon Antonio and the Lieutenant Governor of Antwerp.[72][73] The loss of the garrison was forty killed and 100 wounded;[59] Horace Vere was wounded in the leg with a splinter while two captains and four other officers were killed.[68][70]

After the failure of this assault, many of the Spanish soldiers mutinied to protest the high number of casualties and no gains, blaming their commanders for having led them to certain death.[69] Albert however took no sympathy and ordered the ringleaders, of which there were several, executed.[71]

Departure of Vere

The besiegers had had enough supplies and food to last them for some time and Vere remained for a few months longer, when he was called away by the States General to assume an important command in the field. Vere's parley in December was met with muted criticism however but the repulse of the assault had overshadowed this.[74] Vere left Ostend on 7 March, accompanied by his brother Horace and John Ogle as well as the majority of his English companies,[68][75] but the remaining English troops continued to fight for the Dutch until the end.[76] Colonel Zelandés Frederic van Dorp, the new governor, arrived with a fresh rotation of eight Dutch and Frisian companies and by June more reinforcements put the garrison at 5,000 men in total.[35][77]

In July 1602 Maurice launched an offensive, who after being joined by Francis Vere besieged Grave.[76] A slow siege was conducted and after forcing away a Spanish relief attempt took the surrender of the town on 18 September, and continued their advance through Brabant.[78]

There were no more assaults on Ostend throughout the rest of 1602, but there was an outbreak of pestilence during the summer for both armies causing loss of life and disease.[79] Another thirty six Dutch infantry companies arrived in November 1602 on a rotation replacing those who had stayed the longest.[78] Spanish attempts to prevent the passage of the ships entering Ostend by bombardment failed.[77] The Spanish had built a large platform near the Western dunes and contented themselves with bombarding the town from there.[72]

On the last day of the year in 1602 a huge fleet arrived with provisions to last many more months and again the Spanish failed to stop the ships entering.[74] The relief included cows, sheep, wine, bread, and other foodstuffs enough to supply one of the largest cities in Europe.[80] As a result, the market provisions were cheaper in Ostend than any other place in Europe at the time.[81]

1603

The siege continued on in 1603 with both sides exchanging artillery; in the first few months the Spanish had unsuccessfully tried again to stop Ostend from being provisioned by Dutch and English ships.[68]

Diplomacy

Queen Elizabeth I died in March 1603, and the subsequent succession of James I led to diplomatic talks.[82] Both the ambassadors of Spain, Juan de Acuña Tassis and Juan Fernández de Velasco, congratulated the new monarch but also hoped to seek truces and mutual good faith.[83] James at the same time discouraged the levy of English soldiers to help defend Ostend and declared a ceasefire at sea, in an effort to start peace talks with Spain. The ascension of James I to power effectively ended the Anglo-Spanish war, but this didn't deter English soldiers fighting for the United Provinces.[84] John Ogle, who had been knighted at Woodstock in 1603, continued to recruit English troops to send to Flanders. He would later become the commander of the English forces at Ostend the same year.[85] Meanwhile, Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, heading the delegation of the States, tried to attract the complicity of the new English monarch in the conflict in Flanders, of which the focus was Ostend.[75]

England's answer would not be effective until the signing of the Treaty of London of 1604, in which England and Spain made peace, agreeing not to assist the Dutch rebels.[7] However, as a way to implement honor, the clause of the treaty would only take place once the siege of Ostend ended, with English and Scottish troops still both active in the field fighting with Maurice and in the garrison itself.[59][82]

Assault on the Porcespic & the Squares

On the night of 13 April 1603 a storm raged and tides were dangerously high causing more damage in the town and on the defences.[86] As soon as the storm had passed away the Spanish launched another attack, this time on the "Porcespic" by a force of nearly 8,000 Spanish and Italians.[80] The position though was well defended by a mixture of Dutch, English, and Scots and the attackers were repelled despite managing to gain a foothold on the ramparts.[59][79]

The attack on the redoubt had been a feint however; the Spaniards were at that very moment swarming all over the three external forts, the South Square, the West Square, and the Polder Square.[87] The Spanish had planted rope-ladders, swung themselves over the walls while the fight had been going on at the Porcespic.[86] The three positions were in the hands of the Spanish by the time the fight at the Porcespic was over.[80] Dorp did his best to rally the fugitives, and to encourage those who had remained.[87] The next day the Spaniards consolidated their new positions and they turned the newly captured guns upon the main counterscarp of the town. The cost had been heavy on both sides, around fifteen hundred were casualties – besiegers and besieged- during the assault.[86]

Despite the loss, the besieged strengthened their inner works making sure the Spanish did not exploit the success.[87] The conclusion that another assault had failed despite the capture of the squares had been costly.[80] By taking them at heavy cost and over a long period of time and with more positions to take, some in the Spanish camp began to doubt the military effectiveness of the Archduke and it was decided to replace him as commander in the field.[86][87]

The Spinolas

_Rijksmuseum_SK-A-3953.jpeg.webp)

Genoese brothers Federico and Ambrosio Spinola offered their services to the King of Spain: Federico Spinola had arrived at the Spanish court in Valladolid, where Philip III made available to him six galleys, with which he was to go to Sluis in a potential for galley borne invasion of England as well as a blockade of Ostend.[88] His fleet of galleys though was attacked by the English at Sesimbra Bay losing two galleys, and with the remaining six sailed towards Sluis but was defeated by an Anglo-Dutch squadron in the English Channel losing another three.[89] Frederico would be defeated again and killed in a final battle off Sluis with the Dutch a year later ending any dream of Ostend being blockaded, let alone England invaded.[90]

Meanwhile, Ambrosio Spinola, together with the Count of Fuentes, governor of Milan, recruited 8,000 men in Italy.[91] These were at the expense of their own assets and lending by Genoese bankers, who proceeded to Ostend to reinforce the troops of the Archduke.[92]

After two years of campaigning, Archduke Albert's progress in the siege were scarce: attempts to attack the Old Haven in the west had not had the desired result, and the dike held by Bucquoy in the east had failed stop the boats from entering the city harbour.[79] The only positions captured were the three external squares but the siege by this time had been enormously costly in terms of money and troops.[91][93]

In October 1603, Ambrosio Spinola succeeded the Archduke in the command of the Spanish forces.[91] This replacement initially raised some doubts amongst the commanders since the Genoese aristocrat had very little military experience beyond the study of appropriate books.[94] However, in the field his relations with the soldiers and commanders of the Army of Flanders were soon appreciated; his personal involvement in the conflict and charismatic personality serving as an incentive to the troops.[92] He improved morale and hoped to introduce innovative and inventive ways to take Ostend.[95] One of these was an inventor; Pompeo Targone, a Venetian engineer in the service of the Pope who devised and constructed a number of devices.[92]

The Dutch command also changed; Charles van der Noot was replaced due to ill health by Peter van Gieselles in late 1603.[80]

1604

Attrition

Ambrosio Spinola hoped to avoid the bloody and futile full-scale assaults of his predecessor and instead had his troops provided with a system of field fortification works that slowly advanced towards the northwestern part of Ostend.[96] Although this procedure was costly, it proved to be successful for the Spanish.[95]

He ordered troops to throw up causeways of earth and fascines across the Yperlet stream which was shielded by constructed gabions.[95] The inventions were not helping the Spanish however as Targone's mobile drawbridge mounted on four ten-foot wheels was damaged and immobilized by a single cannon shot; it was then destroyed by more fire from the besieged after which it was abandoned.[92]

Between February and March 1604 the city was badly damaged by severe storms and the Spanish continued to dig trenches ever closer and began constructing a mine under Porcepisc and the West Bulwark.[96]

On 12 March the Spanish launched a determined effort to carry the lesser Polder bulwark. The little fort was soon overwhelmed and the defenders were at last driven out of it and forced to take refuge in the next work; the first attrition success had been registered for Spinola.[97] Gieselles was killed soon after observing the captured position, and was succeeded by Colonel John van Loon, who died just four days later by the impact of a cannonball, his provisional substitute Jacques de Bievry was wounded and evacuated to Zealand.[79]

Jacob van der Meer was next to be appointed as commander of Ostend 1 April, but the next day the Polder ravelin was assaulted by the Spanish.[96] In a bloody action lasting many hours the position was taken but again the cost had been heavy, the defenders were all killed and very few escaped.[97]

On 18 April Spinola ordered another assault this time on the Western ravelin. After a hand to hand action in which great numbers of officers and soldiers were lost on both sides, the fort was eventually carried.[96] This was an important success for the Spanish who had now worked their way with galleries and ditches along the whole length of the counterscarp till they were nearly up with the Porcepsic.[97] Soon after the Spanish assaulted the main Porcepsic itself but were repelled with further losses, but despite this Spinola then undertook a formal siege of the enceinte.[96]

Siege of Sluis

Maurice received the news of the capture of the West and Polder ravelins with astonishment and harboured first fears about the fate of Ostend. He decided to launch an attack at either Ostend or Sluis; the latter was chosen hoping to draw out the Spanish or to capture Sluis, an inland port similar to Ostend as a backup plan.[75][98]

Maurice and his cousin William Louis of Nassau, at the head of a Dutch and English army of 11,000 rising to 18,000 men entered Flanders in April 1604, and laid siege to Sluis on 25 April.[99] Luis de Velasco, General of the Spanish horse, and later Spinola himself attempted to come to the aid of the city but Maurice's forces stood firm and defeated both Velasco and Spinola.[1] As a result, they could not prevent its loss on 19 August, when the governor of the city Mateo Serrano surrendered to the Dutch and English.[98]

New Troy

As a result of the threat that the old counterscarp could be taken or demolished, van der Meer ordered a new one built.[96] A plan for this work had already been sent into the place, and the distinguished English engineer Ralph Dexter arrived with his assistants to carry out the heavy task. He estimated that the labour would take three weeks.[100] The new defensive positions would cut the town in two and whole foundations of houses reduced to rubble by the bombardment were removed.[97]

Meer was told there was a lack of earth so he ordered dead bodies from both sides to be used to shore up the ramparts of this final refuge; heads and bones were used like fascines but they could not offer adequate resistance to cannon fire.[97] Nova Troia: meaning New Troy or Little Troy was bestowed on the last entrenchment of the besieged since they announced that they would hold out there for as long as the ancient Trojans had defended Ilium.[92][101] The new defences were named after old ones including New Helmund, New Polder and New West Bulwark.[100]

By 11 May the Spanish had effected a lodgement in a corner of the Porcepsic and from that point would threaten the new counterscarp before it could be completed.[96] Van der Meer warned the Hague that the garrison was close to exhaustion and was not sure how long he could sustain the defence of the main rampart. He died shortly after however by a musket wound; his position would be taken by Colonel Uytenhoove.[68][95]

On 29 May the long prepared mine was sprung effectively beneath the Porepsic.[102] The Spanish then launched a two-pronged assault, one on the breach and the other on the Polder bulwark.[103] The Spanish soon crowded into the breach and ferocious fighting ensued. After a long and desperate struggle with heavy losses on both sides the Porepsic was at last carried and held by the Spanish. However, the assault on the Polder bulwark was repelled and further attempts to take the position were called off.[99]

On 2 June the mine which he had constructed beneath the Polder bulwark was sprung. A breach forty feet wide was made and the Spanish launched another assault and leaped into the crater.[102] Emerging from the crater and carrying the Polder at last to their surprise were new defences. The besiegers had worked out where the mine was being dug, withdrew from the Polder, and built a new set of defences (known as the New Polder) directly behind with flanking batteries for the impending assault.[103] The musketeers and pikemen protected by their new works were ready and after giving heavy fire then counterattacked towards the shocked and confused assailants.[75] After they reeled back from a brief but severe struggle, the Spanish retreated suffering yet more heavy losses.[102] Spinola called off further assaults for two weeks while the work on another mine under the Western bulwark continued but he knew that he had to take Ostend before Maurice could take Sluis.[101] On 7 June, further reinforcements arrived at the stronghold – five companies in all: two English, two Scottish, and one from Friesland, all of them under the command of Charles Fairfax.[104]

On 17 June the Spanish sprang the mine under the Western bulwark.[103] The assailants attacked the breach and were met again by heavy fire from the besieged with Governor Uytenhoove clad in armour leading his troops. The besieged then launched a counterattack and after an hour of desperate fighting the Spanish were repulsed with heavy loss; Uytenhoove however was severely wounded in the melee.[102] With the repulse in the West Bulwark the Spanish had launched another attack on the Polder. Here too was savage hand-to-hand combat with pikes and clubs pulled from the fascines but the besiegers finally overwhelmed the Polder bulwark, whilst the besieged withdrew to their inner entrenchments.[103] Losses to both sides were high with 1,200 men in total lost in the struggle.[102] Uytenhoove would be replaced by Daniel d'Hertaing; the 5th replacement within the year and the last.[101]

On 25 July a convoy managed to get into Ostend with reinforcements of 800 Zealanders which was some compensation but it was to be the last major reinforcement the garrison would get.[101] Soon after unseasonable storms played havoc on the defences of Ostend and with it Dutch supply ships were finding it difficult to make their way into Ostend.[92]

On 22 August two days after the surrender of Sluis, a combination of high tide and another storm swept away a significant proportion of the New Troy shrinking the defenders position further; the Northern defences were abandoned leaving only the Helmund and Sandhill lightly guarded.[103] Eventually this was abandoned as the position could barely be defended and on 13 September the Spanish took possession that had defied them for nearly three years and began to bombard the walls in front of the Old Haven.[101] The position was now untenable, the besieged were now holding out in the rubble strewn old town.[1] The bloody war of attrition had at last succeeded and the garrison sent messengers to Maurice to try and assist.[1]

Surrender

Maurice's capture of Sluis, however, had made it less essential for the Republic to hold on to Ostend; he and the States-General had assessed the situation with William Lodewijk pointing out that any such relief would be difficult.[105] A decision thus was made to grant the Ostend garrison permission to surrender. Daniel d'Hertaing thus decided to send away all the Spanish deserters, heretical preachers, and other potential troublemakers that might have caused problems during the surrender.[72][101] Fighting, however, continued during the days preceding the capitulation; Charles Fairfax, the commander of the English companies still fighting at Ostend, was killed in battle on 17 September.[106]

Finally, an accord was signed on 20 September; d'Hertaing surrendered the city to the forces of Ambrosio Spinola.[4] The articles of capitulation granted the defenders full military honours.[105]

Aftermath

The garrison of no more than 3,000[4] to 3,500[107] marched out with flags flying and drums beating and were allowed to go to Flushing without harm while Spinola entertained the officers at a banquet.[108] At this point the Spaniards and their empire troops had lost between 60,000 and 70,000 men in the fighting.[2][105] The Dutch and their allies had lost in the region of 30,000 to 40,000; records state that nearly 1,000 healthy soldiers were needed every month to replace the injured, dead and sick.[75] Between July 1601 and June 1604 a total of 151 Dutch and English companies served in Ostend alongside to the figure of 2,800.[109]

After the surrender, the Spanish army entered a completely devastated city that shocked many; Isabella wept at the desolation.[108][110] Three years, two months and two weeks of siege under almost constant fire of artillery as well as defence efforts to rebuild the walls at the expense of the buildings had left Ostend but a wasteland of rubble.[111]

Of the 3,000 civilians in Ostend, the majority had left en masse during the early part of the siege, and by the end only two civilians remained: the wife of a freebooter and her paramour, a journeyman blacksmith.[108]

After the eventual capture, Ambrosio Spinola was appointed field marshal general and supreme commander of the army in Flanders while Juan de Ribas, was made the new Governor of Ostend.[112]

Meanwhile, the garrison arrived at the newly captured Sluis, and Maurice received them with the pomp and ceremony and both officers and private men were promoted or otherwise rewarded.[108][113]

The Habsburg authorities considered the capture of Ostend as a propaganda incentive, but the time, money and heavy casualties invested in the siege turned this into a propaganda failure.[108] The economic and military fatigue from the long siege would force both sides to maintain a small truce during the winter of 1604–1605.[79] By the end of that year however, Spinola seized the initiative, bringing the war north of the great rivers for the first time since 1594.[114] Under Spinola, the Spanish made major advances into Dutch territory, capturing Oldenzaal, Lingen, Rijnberk and Groenlo despite the efforts of Maurice.[115] The Spanish did not repeat the success that Maurice had achieved from 1590–1600, but Spinola had made significant gains in a short time and had caused panic in the Republic when he invaded the Zutphen quarter of Gelderland, showing that the interior of the Republic was still vulnerable to Spanish attack.[116][117] However, Spinola was satisfied with the psychological effect of his incursion and did not press the attack. Maurice decided on a rare autumn campaign in an attempt to close the apparent gap in the Republic's eastern defences. He retook Lochem, but his siege of Oldenzaal failed in November 1606. This was the last major campaign on both sides before the truce that was concluded in 1609. The strategic result of the Spanish gains of 1605–06 was that the Twenthe and Zutphen quarters were to remain a kind of no man's land right down to 1633, during which they were forced to pay tribute to the Spanish forces that often roamed there at will.[118]

The Spanish strategic intent to wrest from the Dutch their only military port in the western part of the North Sea, was offset by the conquest of Sluis by Maurice,[107] which thereafter came to replace Ostend as a base of operations for the Dutch military.[119][120] In 1605 the Dutch East India Company (VoC) made serious inroads into the Portuguese spice trade, by setting up bases in the Moluccas.[121] These advances signalled a potential threat that the conflict might spread further in the Spanish overseas empire. That threat became more apparent when the Dutch scored a major naval victory over the Spanish fleet intended to find the merchant ships of the VoC at Gibraltar in 1607.[114] In addition, the scale of the Ostend siege and Spinola's subsequent campaign had exhausted the Spanish treasury so much that in November 1607 Philip III announced a suspension of payments after the Spanish Royal Treasury had declared bankruptcy.[7][122] The balance of power had led to a balance of exhaustion and after decades of war, both sides were finally prepared to open negotiations leading to the Twelve Years' Truce.[1][119] As a result, the draining Ostend siege has been accounted a Pyrrhic victory for Spain.[111][116][123][124]

Analysis

The siege of Ostend was the longest military campaign of the Eighty Years' War, and one of the longest and bloodiest sieges in world history: more than 100,000 people were killed, wounded or succumbed to disease; on each side, a precise number of casualties is impossible to pin down.[1][10] Four hundred years after the siege, in the refurbishment of the city, human remains were still being discovered.[125]

The siege involved people of different lands and religions. Pope Clement VIII had supported the Spanish cause, sending money and military advisers to the siege. Emanuel van Meteren, one of the chroniclers of the siege, defined Ostend as "a potpourri of nationalities".[95]

Military engineering

With Ostend being supplied from the sea, regular siege warfare techniques were infeasible. The royal army's military engineers were forced to devise new methods to facilitate the capture of the town.[72] The Italian architect Pompeo Targone had many devices designed for this purpose but in the end they were largely ineffective.[126]

School of war

According to American historian John Lothrop Motley and others, the siege of Ostend became progressively known as a 'great academy' in which the science and the art of war taught by the most skilful practitioners to all of Europe.[127] Many names were given to the siege by pamphlets such as Military school of Europe, War College and the New Troy.[127]

Distinguished families in Europe flocked to the inside and outside of Ostend. Many from Scotland and France as well as England and Holland went to learn of the art of war under Francis Vere whom they considered a distinguished veteran, despite the act that he was considerably annoyed by all the attention.[128]

Legacy and anecdotes

- The Ostend campaign was widely covered in the media of the time. The newspaper "Belägerung der Statt Ostende" (siege of Ostend by Anonymous), circulated throughout Europe and was translated into several languages.[129]

- Sebastian Vrancx, Cornelis de Wael, Peter Snayers created paintings and prints of the siege.

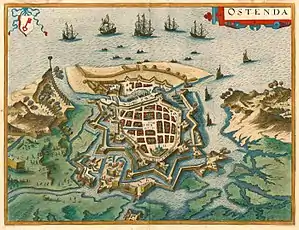

- Cartographers Floris Balthasar and Joan Blaeu, drew maps of the siege.

- Don Giovanni de' Medici reported extensively about Pompeo Targoni's military devices and accompanied his letters with sketches and models of the siege of Ostend. Medici ordered his draughtsman to make a huge scale model of the town and defences.[130]

- Guido Bentivoglio, Emanuel van Meteren, Hugo Grotius notable historians of the time, were among the witnesses who recorded their experiences. The Leiden printer and publisher, Hendrick van Haestens provided accounts of the fighting in three publications.[131]

- Cyril Tourneur who was at Ostend from 1601–02 – references the parley stratagem employed by Francis Vere in The Atheist's Tragedy[129]

- The Dutch dead included Hendrick van Rensselaer the father of Kiliaen van Rensselaer, ancestor of the prominent American political family – the van Rensselaer family of New York.[132]

- According to legend, the Archduchess Isabella Clara Eugenia promised not to change her underwear until the city of Ostend had been conquered. The long duration of the siege led to the colour of her clothes white to dark.[133][134]

- In 1603 the Dutch minted a commemorative medal to the siege of Ostend with a satirical theme, on the obverse of the coin, a fox, representing Spain, looking up at a rooster in a tree, symbolizing Ostend. On the reverse, a map of the city. The obverse of this jeton refers to Aesop's fable of the Fox and the Crow/rooster. This fable warns against listening to flattery.[135]

- Jeroni Desclergue, born in Montblanc, Tarragona, Spain, stemmed from the family who lived at the Casal dels Desclergues on the town square, was a member of the Corts of Barcelona in 1599, and was killed during the Siege of Ostend in 1604.[136] His son, Antoni Desclergue, born in Barcelona, equally had a military career.[137]

- The artillery fire against the city became so numerous and intense that the cannonballs fired by the Spanish guns were piled on the outside of the city walls by the defenders. The new cannon shots made them bounce like marbles.[12]

Cornelis de Wael's depiction of the siege of Ostend

Cornelis de Wael's depiction of the siege of Ostend pamphlets regarding the siege

pamphlets regarding the siege Reconstruction of siege material

Reconstruction of siege material Dutch commemorative coin of the siege

Dutch commemorative coin of the siege

References

Notes

- ^ Note A: The battle has been noted as a Pyrrhic victory for Spain[17][138]

- Moltey, (1869) p 754 For three years Ostend had occupied the entire Spanish army exhausting entirely the resources of Spain while leaving the Dutch free to increase their wealth and power by trade and commerce. It had paid to defend Ostend

- Simoni, (2003) p 10 A pyrrhic victory

- Sandler, (2002) p 650 was at best a pyrrhic victory

- ^ Note B: van Nimwegen p 143 these were refreshed by rotation via the North Sea

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Motley, John Lothrop (1898). The Rise of the Dutch Republic, Entire 1566–74. Harvard University: Harper & brothers. pp. 751–54.

- 1 2 3 Tucker p 13

- 1 2 van Nimwegen p 189

- 1 2 3 4 5 Motley, John Lothrop (1869). History of the United Netherlands from the death of William the silent to the Synod of Dort, with a full view of the English-Dutch struggle against Spain, and of the origin and destruction of the Spanish armada, Volume 4. Oxford University. pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Bertodano, Joseph (1740). Coleccion De Los Tratados. p. 479.

- ↑ Keightley, Thomas (1830). Outlines of History Cabinet cyclopaedia. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green; and John Taylor. p. 351.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cooper pp 263–65

- ↑ Knight, Charles Raleigh: Historical records of The Buffs, East Kent Regiment (3rd Foot) formerly designated the Holland Regiment and Prince George of Denmark's Regiment. Vol I. London, Gale & Polden, 1905, p 50

- ↑ Simoni p.10

- 1 2 Belleroche p 14

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 van Nimwegen pp 171–73

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Duffy p 85

- ↑ Fissel p 188

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Markham pp 308–10

- ↑ Edmundson pp 102–03

- ↑ Israel (1998), p.260

- 1 2 Cortés, Manuel Lomas (2008). La expulsión de los moriscos del Reino de Aragón: política y administración de una deportación (1609–1611). Centro de Estudios Mudéjares. p. 38. ISBN 9788496053311.

- ↑ Malland p 31 It was in many respects a Pyrrhic victory

- ↑ Ghelderode p 5

- ↑ Motley p. 754

- ↑ Tracy, pp 75–78

- ↑ Israel (1997), pp 180–81

- ↑ Israel (1997) p 191

- 1 2 3 4 5 Belleroche pp 23–26

- ↑ Israel, p 213

- ↑ Glete pp 155–56

- ↑ Naphy p 107

- ↑ Wedgwood p 55

- ↑ Munck p 51

- ↑ Williams p 125

- 1 2 Parthesius p 11

- 1 2 Borman pp 224–25

- 1 2 3 4 5 Knight p 49

- ↑ Duffy p 59

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Motley pp 57–59

- 1 2 Parker/Martin pp 126–127

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fissel pp 184–85

- 1 2 3 Belleroche pp 29–33

- ↑ Allen p 123

- ↑ Belleroche p 15

- ↑ Walton, Clifford Elliot (1894). History of the British Standing Army. A.D. 1660 to 1700. Harrison and Sons. p. 362. ISBN 9785879426748.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dalton pp 75–76

- ↑ Fissel p 170

- 1 2 3 Belleroche pp 40–42

- 1 2 3 4 Motley pp 60 – 61

- ↑ Dunthorne p 223

- 1 2 3 4 Lee, Sidney, ed. (1899). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 58. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 232–33.

- ↑ Dunthorne p 62

- 1 2 van Nimwegen pp 174–76

- 1 2 3 4 5 Borman pp 230- 32

- ↑ Belleroche p 43

- 1 2 Belleroche pp 49–50

- ↑ Edelman p 338

- ↑ Markham pp 317–18

- ↑ Nicholas, A. H. (1835). The Republic of Letters: A Republication of Standard Literature, Volume 4. Pennsylvania State University: G. Dearborn. pp. 66–67.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Belleroche pp 51–53

- 1 2 Motley pp 69–70

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Markham pp 318–23

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Knight pp 51–52

- 1 2 Motley pp 72 – 74

- 1 2 3 4 5 van Nimwegen pp 178–80

- 1 2 3 4 Motley pp 75- 81

- 1 2 3 4 5 Markham pp 323–5

- 1 2 3 Simoni pp 97–8

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fissel pp 186

- 1 2 3 4 5 Motley pp 82 – 83

- 1 2 3 4 Belleroche pp 54-56-

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Trim, D. J. B. (2004). Vere, Horace, Baron Vere of Tilbury (1565–1635) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Motley pp 84 – 86

- 1 2 3 4 5 Markham pp 326–29

- 1 2 3 4 Belleroche pp 58–60

- 1 2 3 4 5 Duffy p 86

- ↑ Firth, Charles Harding (1693). Stuart Tracts, 1603–1693 Volume 7 of English garner. E. P. Dutton and Company Limited. p. 209.

- 1 2 Belleroche pp 61–62

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fissel pp 186–87

- 1 2 Williams 1998, p. 380.

- 1 2 van Nimwegen pp 180–82

- 1 2 Motley pp 104–05

- 1 2 3 4 5 Markham pp 330–32

- 1 2 3 4 5 Belleroche pp 65–66

- ↑ Motley p 109

- 1 2 Rowse p 413

- ↑ van Nimwegen p 187

- ↑ Hammer, Paul (2003). Elizabeth's Wars: War, Government and Society in Tudor England, 1544–1604. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 234. ISBN 0230629768.

- ↑ Arshagouni Papazian, Mary (2003). ""Souldiers of one army" John Donne and the Army of the States General as an international Protestant crossroads, 1595–1625". John Donne and the Protestant Reformation: New Perspectives. Wayne State University Press. p. 166. ISBN 0814337597.

- 1 2 3 4 Motley pp 111–13

- 1 2 3 4 van Nimwegen pp 183–84

- ↑ Belleroche p 67

- ↑ Motley pp 106–09

- ↑ Wernham pp 400–01

- 1 2 3 van Nimwegen p 185

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Duffy pp 88–9

- ↑ Motley pp 118

- ↑ Belleroche p 70

- 1 2 3 4 5 Motley pp 171–72

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Belleroche pp 72–73

- 1 2 3 4 5 Motley pp 175–77

- 1 2 Motley (1869) pp 189–98

- 1 2 Knight p 53

- 1 2 Simoni pp 189–90

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 van Nimwegen pp 185–87

- 1 2 3 4 5 Motley (1869) pp 180–81

- 1 2 3 4 5 Belleroche pp 75–76

- ↑ "Reports". Great Britain. Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts: 117. 1936.

- 1 2 3 Belleroche pp 77–78

- ↑ Arshagouni Papazian, Mary (2003). ""Souldiers of one army" John Donne and the Army of the States General as an international Protestant crossroads, 1595–1625". John Donne and the Protestant Reformation: New Perspectives. Wayne State University Press. p. 187. ISBN 0814337597.

- 1 2 Knight p 54

- 1 2 3 4 5 Motley pp 201–02

- ↑ van Nimwegen p 143

- ↑ Young, Alexander (1895). History of the Netherlands (Holland and Belgium). The Werner school and family library: Werner Company. p. 483.

- 1 2 Belleroche pp. 78

- ↑ De Montpleinchamp, M (1870). Histoire de l'archiduc Albert: gouverneur général puis prince souverain de la Belgique Volume 34. Ghent University: Société de l'histoire de Belgique. p. 234.

- ↑ Astley, Terry (1795). An Historical Account of the British Regiments Employed Since the Reign of Queen Elizabeth and King James I. in the Formation and Defence of the Dutch Republic. University of Michigan: T. Kay. p. 14.

- 1 2 Allen p 233

- ↑ Belleroche pp 82–83

- 1 2 Malland p 31

- ↑ Markham p 331-32

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 261–2

- 1 2 Parker p 232

- ↑ Edmundson p 102-03

- ↑ Israel (1982) pp 5–9

- ↑ Alcalá-Zamora p 30

- ↑ Edmundson p 102-03 Albert and Isabella entered Ostend in triumph, but it was a Pyrrhic victory

- ↑ Degroot 2018, p. 185.

- ↑ "Archaeology in Flanders". Marine Biology Research group. Ghent University.

- ↑ Simoni p 154

- 1 2 Motley pp 63 – 64

- ↑ Dunthorne p 75

- 1 2 Hoenselaars pp 27–8

- ↑ Cools, Keblusek & Noldus p 92

- ↑ Simoni p 8

- ↑ Spooner (1907), p. 6

- ↑ Maerz p 49

- ↑ disraeli p 94–95

- ↑ Jeton1603 (Dordrecht)

- ↑ Declercq, Nico F. (2021). "Chapter 18: Jeroni Desclergue y Cortes (DC05) & Felipa de Montoya". The Desclergues of la Villa Ducal de Montblanc. Nico F. Declercq. pp. 193–288. ISBN 9789083176901.

- ↑ Declercq, Nico F. (2021). "Chapter 23: Antoni Desclergue y de Montoya (DC06)". The Desclergues of la Villa Ducal de Montblanc. Nico F. Declercq. pp. 315–372. ISBN 9789083176901.

- ↑ Castellón, Enrique López (1985). Historia de Castilla y León. 6, La crisis del siglo XVII: de Felipe III a Carlos II, Volume 6. Ediciones Reno. p. 66. ISBN 9788486155063.

Bibliography

- Allen, Paul C. (2000). Philip III and the Pax Hispanica, 1598–1621: The Failure of Grand Strategy. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07682-7.

- Belleroche, Edward (2012). The Siege of Ostend; Or the New Troy, 1601–1604. General Books. ISBN 978-1151203199.

- Cools, Keblusek & Noldus, Hans, Marika & Badeloch (2006). Your Humble Servant: Agents in Early Modern Europe. Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 9789065509086.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Borman, Tracy (1997). Sir Francis Vere in the Netherlands, 1589–1603: A Re-evaluation of His Career as Sergeant Major General of Elizabeth I's Troops. University of Hull.

- Cooper, J. P (1979). The Decline of Spain and the Thirty Years War, 1609–59, Volume 4 of The New Cambridge Modern History. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521297134.

- Dalton, Charles (2012). Life and Times of General Sir Edward Cecil, Viscount Wimbledon, Colonel of an English Regiment in the Dutch Service, 1605–1631, and One of His Majesty. HardPress. ISBN 9781407753157.

- Degroot, Dagomar (2018). The Frigid Golden Age Climate Change, the Little Ice Age, and the Dutch Republic, 1560-1720. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108419314.

- Declercq, Nico F. (2021). "Chapter 18.3.27: His Participation in the Siege of Ostend 1602-1604 & Chapter 20: The Siege of Ostend". The Desclergues of la Villa Ducal de Montblanc. Nico F. Declercq. ISBN 9789083176901.

- Duerloo, Luc (2013). Dynasty and Piety: Archduke Albert (1598–1621) and Habsburg Political Culture in an Age of Religious Wars. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 9781409483069.

- Duffy, Christopher (2013). Siege Warfare: The Fortress in the Early Modern World 1494–1660, Volume 1 of Siege warfare. Routledge. ISBN 9781136607875.

- Dunthorne, Hugh (2013). Britain and the Dutch Revolt 1560–1700. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107244313.

- D'Israeli, Isaac (1823). "Anecdotes of Fashion". Curiosities of Literature. Vol. II (7th ed.). London: John Murray.

- Edelman, Charles (2004). Shakespeare's Military Language: A Dictionary. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9780826477774.

- Edmundson, George (2013). History of Holland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107660892.

- Esser, Raingard (2012). The Politics of Memory: The Writing of Partition in the Seventeenth-Century Low Countries. BRILL. ISBN 9789004208070.

- Fissel, Mark Charles (2001). English warfare, 1511–1642; Warfare and history. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21481-0.

- Ghelderode, Michel de (1990). The Siege of Ostend: The Actor Makes His Exit; Transfiguration in the Circus. Host Publications. ISBN 9780924047039.

- Glete, J (2002). War and the State in Early Modern Europe. Spain, the Dutch Republic and Sweden as Fiscal-Military States, 1500–1660. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22645-7.

- Hoenselaars, A. J. (1994). Reclamations of Shakespeare Volume 15 of DQR studies in literature. Rodopi. ISBN 9789051836394.

- Hume & Armstrong, Martin Andrew Sharp & Edward (1925). Spain: Its Greatness and Decay, 1479–1788 (Cambridge historical series). CUP Archive.

- van der Hoeven, Marco (1997). Exercise of Arms: Warfare in the Netherlands, 1568–1648, Volume 1. Brill. ISBN 9789004107274.

- Israel, Jonathan Irvine (1997). Conflicts of Empires: Spain, the Low Countries and the Struggle for World Supremacy, 1585–1713. Continuum. ISBN 9780826435538.

- Israel, Jonathan Irvine (1998). The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness and Fall, 1477–1806 Oxford history of early modern Europe. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198207344.

- Israel, Jonathan Irvine (1982). The Dutch Republic and the Hispanic World, 1606–1661. Clarendon. ISBN 978-0-19-821998-9.

- Maland, David (1980). Europe at war 1600–1650. Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 9780847662135.

- Maerz, Aloys John; Paul, Morris Rea (1930). A Dictionary of Color. McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 49 Plate 13 Color Sample K7, 197.

- Markham, C. R (2007). The Fighting Veres: Lives Of Sir Francis Vere And Sir Horace Vere. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1432549053.

- Munck, Thomas (1990). Seventeenth-Century Europe: State, Conflict and Social Order in Europe 1598–1700. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403936196.

- Naphy, William G. (2011). The Protestant Revolution: From Martin Luther to Martin Luther King Jr. Random House. ISBN 9781446416891.

- Nolan, Cathal J. (2006). The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000–1650: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313337338.

- Martin/Parker, Colin/Geoffrey (1989). The Spanish Armada: Revised Edition. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1901341140.

- Parker, Geoffrey (1989). España y la rebelión de Flandes. NEREA. ISBN 9788486763268.

- Parthesius, Robert (2014). Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters: The Development of the Dutch East India Company (Voc) Shipping Network in Asia 1595–1660). Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-9053565179.

- Rowse, A. L (1973). The Expansion of Elizabethan England. Cardinal Books. ISBN 978-0351180644.

- Sandler, Stanley (2002). Ground Warfare: An International Encyclopaedia, Volume 1. ABC Clio. ISBN 9781576073445.

- Simoni, Anna E. C (2003). Ostend Story: Early Tales of the Great Siege and the Mediating Role of Henrick Van Haestens (III ed.). Hes & De Graaf Pub B V. ISBN 9789061941590.

- Tucker, Spencer C (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851096725.

- van Nimwegen, Olaf (2010). The Dutch Army and the Military Revolutions, 1588–1688 Volume 31 of Warfare in History Series. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781843835752.

- Wedgwood, C. V (2005). The Thirty Years War. New York Review Books Classics. ISBN 978-1590171462.

- Wernham, R.B (1994). The Return of the Armadas: The Last Years of the Elizabethan Wars Against Spain 1595–1603. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820443-5.

- Williams, Patrick. (2006). The Great Favourite: the Duke of Lerma and the court and government of Philip III of Spain, 1598–1621. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719051371.

- Williams, Penry (1998). The Later Tudors: England, 1547–1603. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192880446.

- van der Hoeven, Marco (1997). Exercise of Arms: Warfare in the Netherlands, 1568–1648 Volume 1. BRILL. ISBN 9789004107274.

- Alcalá-Zamora, José N. (2005). La España y el Cervantes del primer Quijote – Volume 18 of Serie Estudios / Real Academia de la Historia / Real Academia de la Historia Madrid: Serie Estudios. Real Academia de la Historia. ISBN 9788495983633.

Journals

- Gardham, Julie (March 2004). "Belägerung der Statt Ostende". University of Glasgow's Special Collections Department.