বাঙ্গালী হিন্দু | |

|---|---|

| |

Durga Puja, the most notable Hindu festival for Bengali Hindus. | |

| Total population | |

| c. 80 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 65,700,000–67,200,000, including 55,000,000 in West Bengal,[1] 6,000,000-7,500,000 in Assam,[2][3] 2,500,000 in Jharkhand and 2,200,000 in Tripura | |

| 13,130,109 (2022 census)[4] | |

| 200,000 | |

| 135,000[5][6] | |

| 50,000[7][8][9][10] | |

| 15,000[11][12][13] | |

| 3,000[14] | |

| 1,500[15] | |

| Languages | |

| Bengali (mother tongue), Sanskrit (liturgical), Hindi (official and second language in India), English and numerous other languages in the Indian diaspora | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism (Shaktism and Vaishnavism) | |

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Bengalis |

|---|

|

Bengali Hindus (Bengali: বাঙ্গালী হিন্দু/বাঙালি হিন্দু, romanized: Bāṅgālī Hindu/Bāṅāli Hindu) are an ethnoreligious population who make up the majority in the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Jharkhand, and Assam's Barak Valley region. In Bangladesh, they form the largest minority. They are adherents of Hinduism and are native to the Bengal region in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent. Comprising about one-thirds of the global Bengali population, they are the second-largest ethnic group among Hindus after Hindustani Hindus. Bengali Hindus speak Bengali, which belongs to the Indo-Aryan language family and adhere to Shaktism (majority, the Kalikula tradition) or Vaishnavism (minority, Gaudiya Vaishnavism and Vaishnava-Sahajiya) of their native religion Hinduism with some regional deities. [16][17][18] There are significant numbers of Bengali-speaking Hindus in different Indian states.[19][20] According to the census in 1881, 12.81 per cent of Bengali Hindus belonged to the three upper castes while the rest belonged to the Shudra and Dalit castes.[21]

Around the 8th century, the Bengali language branched off from Magadhi Prakrit, a derivative of Sanskrit that was prevalent in the eastern region of the Indian Subcontinent at that time.[22] During the Sena period (11th – 12th century) the Bengali culture developed into a distinct culture, within the civilisation. Bengali Hindus were at the forefront of the Bengal Renaissance in the 19th century, the Bengal region was noted for its participation in the struggle for independence from the British rule.[23][24] At the time of the independence of India in 1947, the province of Bengal was partitioned between India and East Pakistan, part of the Muslim-majority state of Pakistan. Millions of Bengali Hindus numbering around 25,19,557 (1941–1951) have migrated from East Bengal (later Bangladesh) and settled in West Bengal and other states of India. The migration continued in waves through the fifties and sixties, especially as a results of the 1950 East Pakistan riots, which led to the migration of 4.5 million Hindus to India, according to one estimate.[25] The 1964 East-Pakistan riots caused an estimated 135,000 Hindus to migrate to India.[26] The massacre of East Pakistanis in the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971 led to exodus of millions of Hindus to India.[27]

Ethnonym

The Hindus are a religious group,[28][29][30] native to the Indian subcontinent, speaking a broad range of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages and adhering to the native belief systems, rooted in the Vedas. The word Hindu is popularly believed to be a Persian exonym for the people native to the Indian subcontinent. The word is derived from Sindhu,[31] the Sanskrit name for the river Indus and it initially referred to the people residing to the east of the river. The Hindus are constituted into various ethno-linguistic subgroups, which in spite of being culturally diverse, share a common bond of unity.[32]

The word Bengali is derived from the Bengali word bangali. The English word Bengali denoting the people as well as the language is derived from the English word Bengal denoting the region, which itself is derived ultimately from the Bengali word Vanga which was one of the five historical kingdoms of Eastern India. According to Harivamsa, Bali, the king of the asuras had five sons from his wife Sudeshna through sage Dirghatama. The five sons namely Anga, Vanga, Kalinga, Pundra and Sumha went on to found five kingdoms of the same name in the eastern region of the Indian subcontinent. In ancient times Vanga proper consisted of the deltaic region between Bhagirathi, Padma and Madhumati, but later on extended to include the regions which now roughly comprise Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal.

In India, they tend to identify themselves as Bengalis[33] while in Bangladesh they tend to identify themselves as Hindus.[34] In the global context, the terms Indian Bengali[35] and Bangladeshi Hindu[36] are respectively used. In India, Bengali generally refers to Bengali Hindus, excluding a significant number of Bengali Muslims who are also ethnically Bengalis.[37] The 'other' is usually identified as 'non-Bengali', a term that generically refers to the Hindu people who are not Bengali speaking, but sometimes specifically used to denote the Hindi speaking population.

Ethnology

The Bengali Hindus constitute of numerous endogamous castes, which are sometimes further subdivided into endogamous subgroups. The caste system evolved over centuries and became more and more complex with time. In the medieval period, several castes were boycotted by the ruling classes from time to time and this isolation continued till the 19th century. These social boycotts were somewhat discriminatory in nature. After the Renaissance, the rigidity of the caste system ceased to a great extent, so much so that the first celebrated intercaste marriage took place as early as in 1925.

The Bengali Hindu families are patriarchal as well as patrilocal and traditionally follow a joint family system. However, due to the Partition and subsequent urbanisation, the joint families have given way to the nuclear families. The Bengali Hindus were traditionally governed by the Dāyabhāga school of law, as opposed to the Mitākṣarā school of law, which governed the other Hindu ethno-linguistic groups. In India, after the promulgation of the Hindu code bills, the Bengali Hindus along with other Hindus are being governed by a uniform Hindu law.

There are two major social subgroups among the Bengali Hindus – the ghotis and the bangals. The Bengali Hindus who emigrated from East Bengal (Bangladesh) at the wake of the Partition and settled in West Bengal, came to known as the bangals, while the native Bengali Hindus of West Bengal came to known as ghotis. For several decades after partition, these two social subgroups possessed marked difference in their accents and their rivalry was manifested in many spheres of life, most notably in the support for the football clubs of East Bengal and Mohun Bagan respectively. Several such differences have eased with passing years.

History

Prehistoric period

20,000-year-old stone weapons including small axes, potteries and charcoal remains have been unearthed from Chandthakurer Danga in Haatpara mouza, 8 km northeast of Sagardighi in Murshidabad.[38] Microliths dating to 10000 BC has been excavated from Birbhanpur, situated in Paschim Bardhaman district on the Damodar River valley near Durgapur. Microliths, potteries, copper fishhooks and iron arrowheads have been found at Pandu Rajar Dhibi.[39]

Ancient period

.jpg.webp)

In the ancient times, some of the Bengali Hindus were seafaring people as evident from Vijay Singha's naval conquest of Lanka,[40][41] the tales of merchants like Chand Sadagar and Dhanapati Saudagor whose ships sailed to far off places for trade and establishment of colonies in South East Asia. By the 3rd century B.C.E. they were united into a powerful state, known to the Greeks as Gangaridai, whose military prowess demoralised Alexander from further expedition to the east.[42][43] Later the region of Bengal came under Maurya, Shunga and Gupta rule. In the 7th century, Shashanka became the independent ruler of Gauda. He successfully fought against his adversaries Harshavardhana and Bhaskaravarmana and protected the sovereignty of his kingdom.[44]

Medieval period

In the middle of the 8th century, the Bengali Hindu nobility democratically elected Gopala as the ruler of Gauda, ushering in an era of peace and prosperity in Bengal, ending almost a century of chaos and confusion. The Buddhist Pala rulers unified Bengal into a single political entity and expanded it into an empire, conquering a major portion of North India. During this time, the Bengali Hindus excelled in art, literature, philosophy, mathematics, sciences and statecraft. The first scriptures in Bengali Charyapada was composed during the Pala rule. The Pala were followed by the Senas who made far reaching changes in the social structure of Bengali Hindus, introducing 36 new castes and orthodox institutions like Kulinism.

The literary progress of the Pala and Sena period came to a halt after the Turkish conquest in the early 13th century. Except for Haridas Datta's Manasar Bhasan no significant literary work was composed for about a century after the conquest.[45] Even though the ruling classes resisted the invaders, Gauda, the centre of Bengal polity, fell to the Islamic invaders. During this period hundreds of temples and monasteries were desecrated. The next attack on the society came from the Islamic missionaries.[46] Local chieftains like Akananda, Dakshin Ray and Mukut Ray, resisted the missionary activities.

During the Pathan occupation of Bengal, some regions were held in sway by different Bengali Hindu rulers. Islam religion gradually spread throughout the Bengal region, and many Bengali Hindus converted to Islam.[47] When the Delhi-based Mughals tried to bring Bengal under their direct rule, the Bengali chiefs along with some Bengali Muslims consolidated themselves into confederacies and resisted the Mughals. After the fall of the confederacies, the Mughals brought a major part of Bengal under their control, and constituted a subah.

Early modern period

During the decline of the Mughal Empire, Nawabs of Bengal (who were Muslim) ruled a large part of Bengal. During the reign of Alivardi Khan. a Nawab, the severe taxation and frequent Maratha raids made the life miserable for the ordinary Bengali Hindus.[48] A section of the Bengali Hindu nobility helped the British East India Company in overthrowing the Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah regime. After obtaining the revenue rights, the East India Company imposed more oppressive taxation. In the famine of 1770, approximately one third of the Bengali population died.[49]

The British began to face stiff resistance in conquering the semi-independent Bengali Hindu kingdoms outside the pale of Muslim occupied Bengal. In some cases, even when their rulers have been captured or killed, the ordinary people began to carry on the fight.[50] These resistances took the form of Chuar (Chuar is a derogatory term used by the Britishers and local zamindars to denote the Bhumij peoples) and Paik Rebellion. These warring people were later listed as criminal tribes[51] and barred from recruitment in the Indian army. In 1766, the British troops were completely routed by the sanyasis and fakirs or the warrior monks at Dinhata, where the latter resorted guerrilla warfare. Bankim Chandra's Anandamath is based on the Famine and consequential Sannyasi Rebellion.[52]

British rule

According to author James Jeremiah Novak, as British rulers took power from Bengal's ruling Muslim class, they strategically catered to Bengali Hindus (a majority in Bengal region at that time).[53] The British rule destroyed the bases of Bengali Muslim society.[53] Bengali Hindus got favours from the British rulers, and experienced development in education and social mobility. In the 19th century, the elite class of Bengali Hindu people underwent radical social reforms and rapid modernisation; the phenomenon came to be known as the Bengal Renaissance.

Public media like press and theatres became vents of nationalist sentiments, apolitical organisations had given way to political platforms, secret revolutionary societies emerged and the society at large became restive.

With rising nationalism among Bengalis, the British rulers applied divide and rule policy, and started to make favours to Bengali Muslims.[53] To keep the rising Bengali Hindu aspirations at bay, the British partitioned the province in 1905 and along with some additional restructuring came up with two provinces – Eastern Bengal & Assam and Bengal itself, in each of which the Bengali Hindus were reduced to minorities. The Bengalis, however, opposed to the Partition tooth and nail, embarked on a political movement of Swadeshi, boycott and revolutionary nationalism. On 28 September 1905, the day of Mahalaya, 50,000 Bengali Hindus resolved before the Mother at Kalighat to boycott foreign goods and stop employing foreigners.[54][55] The British Raj finally annulled the Partition in 1911. The Raj, however, carried out some restructuring, and carved out Bengali Hindu majority districts like Manbhum, Singbhum, Santal Pargana and Purnia awarding them to Bihar and others like Cachar that were awarded to Assam, which effectively made the Bengali Hindus a minority in the united province of Bengal. The Britishers also transferred the capital from Calcutta to New Delhi.

The revolutionary movement gained momentum after the Partition. Bengali revolutionaries collaborated with the Germans during the War to liberate British India. Later the revolutionaries defeated the British army in the Battle of Jalalabad and liberated Chittagong. During the Quit India Movement, the revolutionaries liberated the Tamluk and Contai subdivision of Midnapore district from British rule and established the Tamralipta National Government.[56]

The British, unable to control the revolutionary activities, decided to hinder the Bengali Hindu people through administrative reforms. The Government of India Act 1919 introduced in the 144 member Bengal Legislative Assembly, 46 seats for the Muslims, 59 for the institutions, Europeans & others and left the rest 39 as General,[N 1] where the Bengali Hindus were to scramble for a representation. The situation worsened with the Communal Award of 1932, where in the 250 member Bengal Legislative Assembly a disproportionate 119 seats were reserved for the Muslims, 17 for Europeans, Anglo-Indians & Indian Christians, 34 for the institutions, and the rest 80 were left as General.[57] The Communal Award further divided the Hindus into Scheduled Caste Hindus and Tribal Hindus.[57] Out of the 80 General seats, 10 were reserved for the Scheduled Castes.[N 2] In response the leading Bengali Hindu landholders, lawyers and professionals signed the Bengal Hindu Manifesto on 23 April 1932 rejecting the justification of reservation of separate electorates for Muslims in the Bengal Legislative Assembly.[58] They joined hands with Sikhs and non-Bengali Hindus in attacking Muslims and ultimately it turned out to be a violent reprisal that resulted in heavy casualties of Muslims, finally forcing the government to stop the mayhem.[59] Later in the year, the Muslim League government orchestrated the infamous Noakhali genocide.

After the failure of the United Bengal plan, it became evident that either all of Bengal would go to Pakistan, or it would be partitioned between India and Pakistan. Direct Action Day and the Noakhali genocide prompted the Bengali Hindu leadership to vote for the Partition of Bengal to create a Hindu-majority province.[60] In late April 1947, the Amrita Bazar Patrika published the results of an opinion poll, in which 98% of the Bengali Hindus favoured the creation of a separate homeland.[61] The proposal for the Partition of Bengal was moved in the Legislative Assembly on 20 June 1947, where the Hindu members voted 58–21 in favour of the Partition with two members abstaining.[N 3]

The Boundary Commission awarded the Bengali Hindus a territory far less in proportion to their population which was around 46% of the population of the province, awarding the Bengali Hindu majority district of Khulna to Pakistan. However, some Bengali Muslim majority districts such as Murshidabad and Malda were handed to India.

Post-partition period

After the Partition, the majority of the urban upper class and middle class Bengali Hindu population of East Bengal immigrated to West Bengal. The ones who stayed back were the ones who had significant landed property and believed that they will be able to live peacefully in an Islamic state. However, after the genocide of 1950, Bengali Hindus fled East Bengal in thousands and settled in West Bengal. In 1964, tens of thousands of Bengali Hindus were massacred in East Pakistan and most of the Bengali Hindu owned businesses and properties of Dhaka were permanently destroyed.[62] During the Bangladesh Liberation War, large number of Bengali Hindus were massacred. The Enemy Property Act of the Pakistan regime which is still in force in the new incarnation of Vested Property Act, has been used by successive Bangladeshi governments to seize the properties of the Hindu minorities who left the country during the Partition of India and Bangladesh liberation war. According to Professor Abul Barkat of Dhaka University, the Act has been used to misappropriate 2,100,000 acres (8,500 km2) of land from the Bengali Hindus, roughly equivalent to the 45% of the total landed area owned by them.[63]

In Assam's, Assamese dominated Brahmaputra Valley region Bongal Kheda movement (which literally means drive out Bengalis) was happened in the late 1948-80s, where several thousands of Hindu Bengalis was massacred by jingoists Assamese nationalists mob in various parts of Assam and as a result of this jingoist movement, nearly 5 lakh Bengali Hindus were forced to flee from Assam to take shelter in neighbouring West Bengal particularly in Jalpaiguri division in seek for safety.[64][65][66] In the Bengali dominated Barak Valley region of Assam, violence broke out in 1960 and 1961 between Bengali Hindus and ethnic Assamese police over a state bill which would have made Assamese mandatory in the secondary education curriculum. On 19 May 1961, eleven Bengali protesters were killed by Assamese police fired on a demonstration at the Silchar railway station.[67][68][69] Subsequently, the Assam government allowed Bengali as the medium of education and held it as an official position in Barak Valley.[68] The United Liberation Front of Asom, National Democratic Front of Bodoland, Muslim United Liberation Tigers of Assam and National Liberation Front of Tripura militants have selectively targeted the Bengali Hindu people, prompting the latter to form the Bengali Tiger Force.[70]

Discrimination against refugee Bengali Hindu population is not limited to the North East. In Odisha, in a family of ten individuals, only half of them has been recognised as Indians while the rest were branded as Bangladeshis.[71]

The Bengali refugees who had settled in Bihar after the partition of India are denied land owning rights, caste certificates and welfare schemes. However, the Nitish Kumar government had promised to solve this problems and also to raise the status of Bangla as a language in the state.[72]

Geographic distribution

Bengali Hindus constitute a minority ethnic group of the total population in both Bangladesh and India,[73] forming less than 10% of the population in both countries.

West Bengal

Hinduism has existed in Bengal before the 16th century BC and by the third century, Buddhism has also gain popularity in Bengal.[74][75] West Bengal was created in 1947 as an act of Bengali Hindu Homeland Movement to save guard the political, economical, cultural, religious, demographic and land owning rights of Bengali Hindus of undivided Bengal region and as a result predominantly Hindu majority West Bengal became a part of Indian union. The vast majority of Hindus in West Bengal are Bengali Hindus numbering around 5.5 crore out of the total estimated state population of 10 crore,[76][77] but a notable section of non-Bengali Hindus also exist, particularly among Marwaris, Biharis, Odias, Gurkhas, Punjabis, Sindhis, Gujaratis and various tribal communities such as Koch Raj bongshi, Santals, Munda and particularly Adivadis numbering around 1.557 crore comprising rest 15% of the state population.[77][78][79][80]

Bangladesh

Hinduism has been existed in what is now called Bangladesh since the ancient times. In nature, the Bangladeshi Hinduism closely resembles the ritual and customs of Hinduism practised in the Indian state of West Bengal, with which Bangladesh (at one time known as East Bengal) was united until the partition of India. While in Bangladesh, Bengali Hindus are the second largest community with a population of 12.8 million out of 149.77 million people constituting (8.5%) of the country as per 2011 year census.[81][82] But distinct Hindu population also exist among indigenous tribes like Garo, Khasi, Jaintia, Santhal, Bishnupriya Manipuri, Tripuri, Munda, Oraon, Dhanuk etc. In terms of population, Bangladesh is the third largest Hindu populated country in the world after India and Nepal.[83][84][85]

Out of 21 million population of Dhaka as far estimated by 2020, Bengali Hindus are at present the second largest community just after Bengali Muslims in Dhaka numbering around at 1,051,167 (5% of population) and are mainly concentrated in Shankhari Bazaar.[86]

Indian States other than West Bengal

Assam

The Barak Valley comprising the present districts of Cachar, Karimganj and Hailakandi is contiguous to Sylhet (Bengal plains), where the Bengali Hindus, according to historian J.B. Bhattacharjee, had settled well before the colonial period, influencing the culture of Dimasa Kacharis.[87] Bhattacharjee describes that the Dimasa kings spoke Bengali and the inscriptions and coins written were in Bengali script.[87] Migrations to Cachar increased after the British annexation of the region.[87] Bengalis in plains of Cachar valley were a significant, and sometimes dominant tribe/group/demographic for at least a period since the reign of Dhanya Manikya in the 15th century who hosted several Bengali Brahmin scholars in his court during his reign/rule.[88] The Bengalis have been living in Barak Valley for at least 1,500 years, settling there much earlier than the Koch, Dimasa and the Tripuris.[89] The Koches settled in Barak Valley in the 16th century, while the Dimasas settled in the late 16th - early 17th century A.D respectively.[89] The Muslim population of the Cachar was in majority before it was annexed to the Bengal Presidency of British India in 1832. Mostly farmers, the population of Muslims in the Barak Valley decreased in the late 19th century largely because the fertile lands were occupied by earlier settlers of the region, later those Muslims have immigrated to Un-divided Nagaon region of Assam.[90] A population 85,522 of diverse backgrounds including hill tribes, in 1851, Muslims and Hindus, 30,708 and 30,573 receptively mostly Bengalis, constituted 70% of the total population of Cachar Valley, followed by 10,723 Manipuris, 6,320 Kukis, 5,645 Naga and 2,213 Cachari.[90] Bengali Hindus first came into Assam's Brahmaputra valley during the time of British era of 1826 from neighbouring Bengal region as colonial official workers, bankers, railway employees, bureaucrats and later on during the time Partition of Bengal in 1947.[91] Between the period of first patches (1946-1951), around 274,455 Bengali Hindu refugees have arrived from what is now called Bangladesh (former East Pakistan) in various locations of Assam as permanent settlers and again in second patches between (1952-1958) of the same decade, around 212,545 Bengali Hindus from Bangladesh took shelter in various parts of the state permanently.[92][93] After the 1964 East Pakistan riots many Bengali Hindus have poured into Assam as refugees and the number of Hindu migrants in the state rose to 1,068,455 in 1968 (sharply after 4 years of the riot).[94] The fourth patches numbering around 347,555 have just arrived after Bangladesh liberation war of 1971 as refugees and most of them being Bengali speaking Hindus have decided to stay back in Assam permanently afterwards.[95] Bengali Hindus are now the third largest community in Assam after Assamese people and Bengali Muslims with a population of 6,022,677 (million), comprising (19.3%) of state population as of 2011 census.[96] They are highly concentrated in the Barak Valley region where they a form a slide majority and the population of Bengali Hindus in Barak Valley is 2 million, constituting 55% of the total population of the region.[97][98][99] In Assam's Brahmaputra valley region, their numbers are 4 million covering up 14.5% of the valley population respectively and are mainly concentrated in Hojai District where Bengali are spoken by (53%) of the district population, Goalpara District, Nagaon district, Bongaigaon district, Barpeta District, Kamrup District, Darrang district, Dhubri District, Morigaon district, Tinsukia district, Karbi Anglong, Guwahati, BTAD, Dibrugarh district, Jorhat district, Sonitpur district with percentage ranging 15-25% in all those districts mentioned above.[100]

In January 2019, the Leftist organisation Krishak Mukti Sangram Samiti (KMSS) claimed that there are around 2 million Hindu Bangladeshis in Assam who would become Indian citizens if the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill is passed. BJP, however claimed that only eight lakh Hindu Bangladeshis will get citizenship.[101] The number of Hindu immigrants from Bangladesh in Barak Valley has varied estimates. According to the Assam government, 1.3 lakh such people residing in the Barak Valley are eligible for citizenship if the Citizenship Amendment Act of 2019 becomes a law.[102]

Jharkhand

Most Bengali Hindus came into Jharkhand during the colonial period, brought up by the British as colonial workers mainly from the western part of Bengal.[103] In Jharkhand, the Bengali Hindu population is over 2.5 million comprising 8.09% but the overall Bengali speaking population are a slight majority there and the percentage of Bengali speakers ranges from 38%–40%.[104]

Tripura

The non-tribal population of Tripura, the mostly Bengali-speaking Hindus and Muslims, constitute more than two-thirds of the state's population. The resident and the migrant Bengali population benefitted from the culture and language of the royal house of Tripura thanks to embracement of Hinduism and adoption of Bengali as the state language by the Maharajahs of Tripura much before Indian independence.[105] Since the partition of India, many Bengali Hindus have migrated to Tripura as refugees fleeing religious persecution in Muslim-majority East Pakistan, especially after 1949 and this is primarily attributed by the immigration of 610,000 Bengalis — the figure almost equal to the State's total population in 1951 — from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) between 1947 and 1951.[106] Settlement by Hindu Bengalis increased during the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, where around at that time, nearly 1,381,649 Bengalis (mostly Hindus) have came into various parts of Tripura to take refugees and most of them have settled here permanently afterwards.[107] Parts of the state were shelled by the Pakistan Army during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. Following the war, the Indian government reorganised the North East region to try to improve control of the international borders – three new states came into existence on 21 January 1972: Meghalaya, Manipur, and Tripura.[108] Before independence, most of the population was indigenous.[109] In Tripura, now Bengali Hindus form a clear majority due to immigration from neighbouring East Pakistan during 1947 and 1971 and as a result Tripura has become a Bengali dominant state with Bangla as its official language along with Kokborok and English. Bengali Hindus comprise nearly 60% of the state population which is around 2.2 million whereas native Tripuris are 30% of the state population which is around 1.2 million as of 2011 census.[110][111]

Andaman and Nicobar islands

There is also a significant number of Bengali Hindus residing in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, estimated approximately 100,000 comprising 26%–28% of the population. Bengali is also the most widely spoken language in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, despite it lacking official status.[112]

Myanmar

The Bengali Hindus in Myanmar are present from long back historical times, when they were brought from Bengal region to Arakan region by many Arakanese Kings, especially the Brahmins for the worship and teaching purpose in the Pagoda.[113] Then afterwards 1920, most of them start settling to the urban areas and main cities, mainly in Yangon, Mandalay and in urban areas of Rakhine State. In modern times, they have faced persecution which was mainly started after 1962 coup by Ne Win.

Outside Indian Subcontinent

Both the United States and United Kingdom have large immigrant Bengali Hindu populations, who are mostly from the professional classes and have migrated through education and employment. Former Cricketer Isa Guha and Rhona Mitra are prominent descendants of the Bengali Hindu diaspora.

Culture

Cuisine

Bengali cuisine is mainly influenced by the diet habits similar to the Hindus and includes a very large variety of sweets and dishes.[114] The Bengali sweets includes desserts made by milk, includes Rasgulla, Sandesh, Cham cham, etc.[115] In Hinduism, the consumption of meat is often avoided in diets due to the Hindu principle of ahimsa which prohibits meat consumption. However, Bengali Hindus adore eating meat of goat, chicken, duck and lamb.[116] Most of the Hindus refrain from eating beef. Meat, especially beef is readily consumed in Bangladesh and where it is considered the meal's main course and the Fish curry (or Machher Jhol) with rice is considered as one of the most staple food by both Hindus and Muslims in Bengal.[117]

In West Bengal and Bangladesh, the Bengali Hindu cuisine is mainly based on the geographical basis like rice, which is grown there mostly and fish, which was there because of good water source.[118]

Wedding

Society

Bengali Hindu society used to be caste-oriented throughout centuries and the professional status of men depended exclusively on the hierarchical caste divisions.[119] In traditional Bengali Hindu society, nearly every occupation is carried on by a ranked hierarchy of specialised caste groups such as weaving, pottery, carpentry and blacksmithing. However, with the introduction of British rule and appearance of urban civilisation, the former rural agrarian and artisan economy gradually crumbled and gave way to modern middle class economy. However, agriculture, land tenure, farming and fishing form the predominant economic activity in most of the rural area till now.[119][120]

Economy

Literature

The proper Bengali literary history begins with the early Vaishnava literature like the Shreekrishna Kirtana and the Vaishnava padavalis followed by translation literatures like Ramayana and Srikrishna Vijaya. In the medieval period literary works on the life and teachings of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu were composed. This period saw the emergence of Shakta padavalis.[121] The characteristic feature of Bengali Hindu literature in the middle age are the mangalkavyas, that glorify various Hindu gods and goddesses often using folkloristic backgrounds.

The early modern period saw a flurry in the literary activity especially after the emergence of the Bengali press. The first Bengali prose Raja Pratapaditya Charitra was written during this time. The Renaissance saw a rapid development in modern Bengali literature.[122] Most of the epics, poems, novels, short stories and dramas of the modern classical literature were written during this period. The Bengal Literary Society that later came to be known as Bangiya Sahitya Parishad was founded. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee wrote commentaries on Krishna Charita, Dharmattatva, Bhagavad Gita. The literary development during the Renaissance culminated in Tagore's Nobel prize for literature.[123]

In the Post-Partition period, the Bengali Hindus pioneered the Hungry generation, Natun Kabita and the little magazine movements. Of late, some of them have made their mark in contemporary English literature.[124]

Art

The Kalighat school of painting flourished in Bengal in the early modern period, and especially after the first paper mill was set up in 1809.[125] During the rise of nationalism in the early 20th century, the Bengali Hindus pioneered the Bengal school of art.[126] It provided the artistic medium of expression to the Hindu nationalist movement.[127] Though the Bengal school later gave way to modernist ideas, it left an enduring legacy. In the post-liberalisation phase of India, modern art acquired a new dimension as young artists like Devajyoti Ray, Sudip Roy and Paresh Maity started gaining international recognition. Devajyoti Ray is known for introducing Pseudorealism, which is one of the most original genres of Indian art today.

Religion

The Bengali Hindus generally follow the beliefs and practices that fall under the broad umbrella of Hinduism.[128] Majority of them follow either Shaktism (the Kalikula tradition) or Vaishnavism (Gaudiya Vaishnavism, Vaishnava-Sahajiya, Bauls), and some follow a synthesis of the two. The Shaktas belong to the upper castes as well as lowest castes and tribes, while the lower middle castes are Vaishnavas.[16] The minor traditions include Shaivites. A small minority is atheist who do not follow any rituals.[129] Brahmoism is also found among Bengali Hindus.[130]

A part of the parent tradition, the Bengali Hindus usually affiliate themselves to one of the many sects that have come to be established as institutionalised forms of the ancient guru-shishya traditions.[131] Major amongst them include the Ramakrishna Mission, Bharat Sevashram Sangha, Bijoy Krishna Goswami, Anukul Thakur, Matua, ISKCON, Gaudiya Mission, Ananda Marga, Ram Thakur etc.[132]

The main devis of the Shakta Kalikula tradition are Kali, Chandi, Jagaddhatri, Durga, as well as regional goddesses such as Bishahari and Manasa, the snake goddesses, Shashthi, the protectress of children, Shitala, the smallpox goddess,Annapurna and Umā (the Bengali name for Parvati).[16]

Festivals

Durga Puja, the largest festival of Bengali Hindus

Durga Puja, the largest festival of Bengali Hindus Kali Puja, a major Hindu festival of Bengal

Kali Puja, a major Hindu festival of Bengal Rath Yatra at Dhamrai in Dhaka district, Bangladesh

Rath Yatra at Dhamrai in Dhaka district, Bangladesh A traditional Durga idol with Chalchitra

A traditional Durga idol with Chalchitra The Bengali Hindu diaspora celebrate Durga Puja all over the world.

The Bengali Hindu diaspora celebrate Durga Puja all over the world.

According to a famous Bengali proverb, there are thirteen festivals in twelve months (Bengali: বারো মাসে তেরো পার্বণ, romanized: Bārō māsē tērō pārbaṇa).[133] Bengali Hindus celebrate all major Indian festivals. The year begins with the Bengali New Year's Day or Pohela Boishakh which usually falls on 15 April. Traditional business establishment commence their fiscal year on this day, with the worship of Lakshmi and Ganesha and inauguration of the halkhata (ledger). People dress in ethnic wear and enjoy ethnic food. Poila Baishakh is followed by Rabindra Jayanti, Rath Yatra and Janmashtami before the commencement of the Pujas.[134]

The puja season begins with the Vishwakarma Puja and is followed up by Durga Puja—the last four days of Navaratri—the greatest and largest Bengali Hindu festival.[16][135][136] It is the commemoration of the victory that teaches none is good and none is evil. Each and every war starts, continues and ends with an objective to fulfill their own minimum demands that is required to exist. The defeated always have to accept the dictations of the victors and the defeated becomes free from the guilt of having defeated in the war and again both victors and defeated become friends. According to Chandi Purana, goddess Durga killed Mahishasura, the demon-like asura and saved the devas. Rama the prince of Ayodhya invoked the blessings of goddess Durga in a battle against Ravana of Lanka. Durga Puja is the commemoration of Rama's victory over Ravana and it ends in Bijoya Dashami. Durga Puja is followed by Kojagari Lakshmi Puja, Kali Puja, Bhai phonta, Jagaddhatri Puja.[137]

The winter solstice is celebrated a Paush Sankranti in mid January, followed by Netaji Jayanti and Saraswati Pooja, a puja dedicated to Goddess of Knowledge and music Goddess Saraswati.[138]

The spring is celebrated in the form of Dolyatra or Holi. The year ends with Charak Puja and Gajan.[139]

Durga Puja became the main religio-cultural celebration within the Bengal diaspora in the West (together with Kali and Saraswati Pujas, if a community is large and prosperous enough).[140]

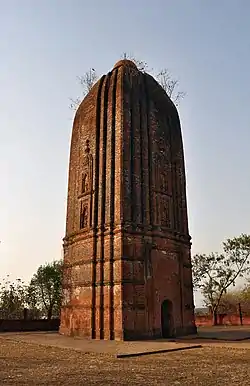

Temple

As per David J. McCutchion, historically the religious architecture in Bengal may be divided into three periods: the early Hindu period (up to the end of the 12th century, or may be a little later in certain areas), the Sultanate period (14th to early 16th century), the Hindu revival period (16th to 19th century).[141] A lot of Odia culture, the Bengal temple architecture has also very much by the Odia architecture.[142]

Dhakeshwari Temple in Dhaka. (Bangladesh)

Dhakeshwari Temple in Dhaka. (Bangladesh) Baro-chala Buro Shiva temple at Jalshara in Paschim Medinipur, West Bengal. (India)

Baro-chala Buro Shiva temple at Jalshara in Paschim Medinipur, West Bengal. (India)

See also

Notes

- ↑ There were no separate electorates for Hindus, in spite of them being minorities in the province.

- ↑ The Caste Hindus were supposed to contest in the 70 General seats. However as per the Poona Pact between Gandhi and Ambedkar, 20 General seats were reserved for Scheduled Castes.

- ↑ Rup Narayan Roy and Jyoti Basu, the two Communist Party MLAs abstained.

References

Citations

- ↑ Datta, Romita (13 November 2020). "The great Hindu vote trick". India Today. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

Hindus add up to about 70 million in Bengal's 100 million population, of which around 55 million are Bengalis.

- ↑ Ali, Zamser (5 December 2019). "EXCLUSIVE: BJP Govt plans to evict 70 lakh Muslims, 60 lakh Bengali Hindus through its Land Policy (2019) in Assam". Sabrang Communications. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

Hence, about 70 lakh Assamese Muslims and 60 lakh Bengali-speaking Hindus face mass evictions and homelessness if the policy is allowed to be passed in the Assembly.

- ↑ "Bengali speaking voters may prove crucial in the second phase of Assam poll". April 2021. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ↑ "Census 2022: Number of Muslims increased in the country". Dhaka Tribune. 27 July 2022. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ↑ "Bengali, Bangla-Bhasa of United Kingdom". Joshua Project. U.S. Center for World Mission. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ "What Are London Kalibari's Aims for the Future?". London Kalibari. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ↑ "Bengali of United States". Joshua Project. U.S. Center for World Mission. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ Terrazas, Aaron (July 2008). "Indian Immigrants in the United States". Migration Policy Institute. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ "Rich & Famous in the US | Padma Rao Sundarji". Outlookindia.com. 22 May 1996. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Lemley, Brad (1 October 2004). "Discover Dialogue: Amar G. Bose". Discover Magazine. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ↑ "Ethnic Origin (247), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census – 20% Sample Data". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ Goa, David J.; Coward, Harold G. "Hinduism". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 July 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ↑ Coward, Harold G.; Hinnells, John R.; Williams, Raymond Brady, eds. (1 February 2012). The South Asian Religious Diaspora in Britain, Canada, and the United States. SUNY series in religion. SUNY Press. p. 153. ISBN 9780791493021. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ Jupp, James, ed. (2001). The Australian people: an encyclopedia of the nation, its people and their origins. Cambridge University Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-521-80789-0. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

Bengali speakers in Australia in 1996 numbered 6553, of whom about half have originated from West Bengal and half from Bangladesh. In addition, there are some who speak English as a mother tongue ... There are no figures for those from West Bengal, but Bangladesh-born numbered 5077 ... there was a Christian minority of about one in ten and a smaller number of Hindus. Indian Bengalis, in contrast, are mainly Hindus.

- ↑ "Indian Associations and portals in Sweden". GaramChai.com. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 McDermott 2005, p. 826.

- ↑ Frawley, David (18 October 2018). What Is Hinduism?: A Guide for the Global Mind. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 26. ISBN 978-93-88038-65-2.

- ↑ Tagore, Rabindranath (1916). The Home and the World ঘরে বাইরে [The Home and the World] (in Bengali). Dover Publications. p. 320. ISBN 9-780-486-82997-5.

- ↑ B.P. Syam Roy (28 September 2015). "Bengal's topsy-turvy population growth". The Statesman. Archived from the original on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ↑ Government of India (2012), "Population by religious community: West Bengal", 2011 Census of India, vol. 36, archived from the original on 10 September 2016, retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ↑ Seal, Anil (1968). The emergence of Indian nationalism: competition and collaboration in the later nineteenth century. London: Cambridge U.P. p. 43. ISBN 9780521096522.

- ↑ Chakrabarti, Kunal; Chakrabarti, Shubhra (22 August 2013). Historical Dictionary of the Bengalis. Scarecrow Press. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-8108-8024-5.

- ↑ "Muslim freedom martyrs of India". Two Circles. 2 October 2009. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "Role of Muslims in the Freedom Movement-II". Radiance Weekly. Archived from the original on 25 December 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ Roy, A. (1980). Genocide of Hindus & Buddhists in East Pakistan (Bangladesh). Delhi: Kranti Prakashan. p. 94. OCLC 13641966.

- ↑ Brady, Thomas F. (5 April 1964). "Moslem-Hindu Violence Flares Again". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ↑ University of Dhaka: 1971 Dhaka University Massacre, 1971 Killing of Bengali Intellectuals, Academic Divisions of University of Dhaka, Aparajeyo Bangl. General Books. September 2013. ISBN 978-1-230-82794-0.

- ↑ Tagore, Rabindranath. "Atmaparichay". Society for Natural Language Technology Research. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ↑ "Hindu (ethnicity)". Indopedia. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ↑ "Hindus ethnic groups". The Hindu. Fairlex. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ↑ Garg, Ganga Ram (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu world (Volume I). Concept Publishing Company. p. 3. ISBN 81-7022-374-1. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ↑ Sharma, Arvind (1 January 2002). "ON HINDU, HINDUSTĀN, HINDUISM, AND HINDUTVA". Numen. 49 (1): 1–36. doi:10.1163/15685270252772759. ISSN 1568-5276.

- ↑ Sandipan Deb (30 August 2004). "In Apu's World". Outlook. Archived from the original on 26 January 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ↑ Ghosh, Shankha (2002). ইছামতীর মশা (Ichhamatir Masha) (in Bengali). Swarnakshar Prakashani. p. 80.

- ↑ Ghosh, Sutama (2007). ""We Are Not All the Same":The Differential Migration, Settlement Patterns and Housing Trajectories of Indian Bengalis and Bangladeshis in Toronto" (PDF). Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ↑ "Bengali Hindu Migrant: Ashim Sen – Bradford". Bangla Stories. Archived from the original on 26 October 2010. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ↑ Bose, Neilesh (2009). Anti-colonialism, regionalism, and cultural autonomy: Bengali Muslim politics, c.1840s – 1952 (PhD). Tufts University. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ↑ Sarkar, Sebanti (28 March 2008). "History of Bengal just got a lot older". The Telegraph. Kolkata. Archived from the original on 1 April 2008. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ↑ Sultana 2003, p. 44.

- ↑ Sen 1993, p. 54.

- ↑ Sengupta, Subodhchandra (1998). Sansad Bangali Charitabhidhan. Vol. 1. Calcutta: Sahitya Samsad. ISBN 978-81-85626-65-9. OCLC 59521727.

- ↑ "When he (Alexander) moved forward with his forces certain men came to inform him that Porus, the king of the country, who was the nephew of that Porus whom he had defeated, had left his kingdom and fled to the nation of Gandaridai... He had obtained from Phegeus a description of the country beyond the Indus: First came a desert which it would take twelve days to traverse; beyond this was the river called the Ganges which had a width of thirty two stadia, and a greater depth than any other Indian river; beyond this again were situated the dominions of the nation of the Prasioi and the Gandaridai, whose king, Xandrammes, had an army of 20,000 horse 200,000 infantry, 2,000 chariots and 4,000 elephants trained and equipped for war".... "Now this (Ganges) river, which is 30 stadia broad, flows from north to south, and empties its water into the ocean forming the eastern boundary of the Gandaridai, a nation which possesses the greatest number of elephants and the largest in size." –Diodorus Siculus (c.90 BC – c.30 BC). Quoted from The Classical Accounts of India, Majumdar 2017, pp. 170–172, 234.

- ↑ Bosworth, A. B (1996). Alexander and the East. Internet Archive. Clarendon Press. pp. 192. ISBN 978-0-19-814991-0.

- ↑ Agrawala, Vasudeva Sharana; Parishad, Bihāra Rāshṭrabhāshā (1969). The Deeds of Harsha: Being a Cultural Study of Bāṇa's Harshacharita. Prithivi Prakashan.

- ↑ Sarkar, Jagadish Narayan (1981). Banglay Hindu-Musalman Samparka (Madhyayuga). Kolkata: Bangiya Sahitya Parishad. p. 53.

- ↑ "When the Islamic missionaries arrived they found in several instances that the conquering armies had destroyed both the temples of revived Hinduism and the monasteries of the older Buddhism; in their place—often on the same sites—they built new shrines. Moreover, they very frequently transferred ancient Hindu and Buddhist stories of mir." Quoted in The Interaction of Islam and Hinduism Archived 11 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ "GlobalFront Homepage". www.globalfront.com. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ↑ Chaudhuri, B.B. (2008). Peasant history of late pre-colonial and colonial India. Pearson Education India, p. 184.

- ↑ Chaudhuri, B. (1983). "Regional Economy (1757–1857): Eastern India, II". In Kumar, Dharma; Desai, Meghnad (eds.). The Cambridge Economic History of India. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-521-22802-2.

- ↑ Sengupta, Nitish K. (2001). History of the Bengali-speaking people. New Delhi: UBS Publishers' Distributors. ISBN 81-7476-355-4. OCLC 49326692.

- ↑ Sinha, Narendra Krishna (1967). The History of Bengal, 1757–1905. University of Calcutta.

- ↑ Bangali Charitabhidhan Volume I. Sansad, p. 489.

- 1 2 3 Novak, James Jeremiah (1993). Bangladesh: Reflections on the Water. Indiana University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-253-34121-1.

- ↑ Das, S.N.(ed). The Bengalis: The People, their History and Culture. Genesis Publishing, p. 214.

- ↑ Beck, Sanderson. Ethics of Civilization Volume 20: South Asia 1800–1950. World Peace Communications

- ↑ Chatterjee, Pranab Kumar (1982). "Quit India Movement of 1942 and the Nature of Urban Response in Bengal". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 43: 687–694. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44141311. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- 1 2 "Constitution of India". Constitution of India. Ch: 2. Government of India. p. 254. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Mitra, N. N., ed. (1932). "The Hindu Polity". The Indian Annual Register. I: 323.

- ↑ Dastidar 2008, p. 189.

- ↑ Fraser, Bashabi; Sengupta, Sheila, eds. (2008). Bengal Partition Stories: An Unclosed Chapter. Anthem Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-1-84331-225-3.

- ↑ Roy 2002, p. 131.

- ↑ Ghosh Dastidar, Sachi (2008). Empire's Last Casualty: Indian Subcontinent's vanishing Hindu and other Minorities. Kolkata: Firma KLM. pp. 131–134. ISBN 978-81-7102-151-2.

- ↑ Barkat, Abul; Zaman, Shafique uz; Khan, Md. Shahnewaz; Poddar, Avijit; Hoque, Saiful; Uddin, M Taher (February 2008). Deprivation of Hindu Minority in Bangladesh: Living With Vested Property. Dhaka: Pathak Shamabesh. pp. 73–74. ASIN B005MXLO3M.

- ↑ Bhattacharjee, Manash Firaq. "We foreigners: What it means to be Bengali in India's Assam". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ "Opinion | Antipathy Towards Bengalis Prime Mover Of Assam Politics | Outlook India Magazine". Outlook. 4 February 2022. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ "Assam protests due to politics of xenophobia". www.asianage.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ↑ Baruah, Sanjib (1999). India Against Itself: Assam and the Politics of Nationality. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 105. ISBN 0-8122-3491-X.

The most notorious 'language riots' in Assam were in 1960 and 1961, before and after the passing of the Official Language Bill by the state Assembly ... There were violent conflicts between ethnic Assamese and Hindu Bengalis ... On the Bengali side, for instance, Paritosh Pal Choudhury's book Cacharer Kanna (The Cry of Cachar) has a frontispiece with pictures of eleven garlanded dead bodies of people killed in 1961 as a result of police firing on a demonstration in support of Bengali in Silchar.

- 1 2 "Silchar rly station to be renamed soon". The Times of India. Silchar. 9 June 2009. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ Ganguly, M. (20 May 2009). "All for love of language". The Telegraph. Ranchi. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ "Now Bengali militants raise heads in Assam". The Indian Express. India. 18 August 1998. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ "Indians, Bangladeshis in same Orissa family!". The Indian Express. Kendrapara. 29 January 2009. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ Kumar, Madhuri (26 October 2010). "JD(U) Bangla bait for Bengalis in Bihar". The Times of India. Patna. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ Togawa, Masahiko (2008). "Hindu Minority in Bangladesh – Migration, Marginalization and Minority Politics in Postcolonial South Asia" (PDF). Discussion Paper Series. Hiroshima University. 6: 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ↑ Mukherjee, Ishan. "The historical roots of Hindu majoritarianism in West Bengal". The Caravan. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "The rich history of Buddhism in Bengal". Dhaka Tribune. 8 October 2017. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ Datta, Romita (13 November 2020). "The great Hindu vote trick". India Today. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- 1 2 "Great Hindu Voting Trick-Nation News". India Today- Get the Latest India news. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ↑ "Population of West Bengal-West Bengal Population 2021". India Guide- Festivals, Culture, City Guide, Weddings, Population,Indianonlinepages.com. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ↑ "Opinion divided on most non-Bengali voters favouring BJP in West Bengal". National Herald: Live News Today,India News,Top Headlines,Political and World News. 3 April 2021. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ↑ "THE GREAT HINDU VOTE TRICK". Magzter. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ "Population & Housing Census-2011: Union Statistics" (PDF). Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. March 2014. p. xiii. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ↑ "Bangladesh Population 1950-2021". www.macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ↑ Haider, M. Moinuddin; Rahman, Mizanur; Kamal, Nahid (6 May 2019). "Hindu Population Growth in Bangladesh: A Demographic Puzzle". Journal of Religion and Demography. 6 (1): 123–148. doi:10.1163/2589742X-00601003. ISSN 2589-7411. S2CID 189978272. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ↑ "Do Hindus feel threatened in Bangladesh?". Do Hindus feel threatened in Bangladesh?. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "Why Narendra Modi's visit to Bangladesh led to 12 deaths". BBC News. 31 March 2021. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ↑ Pramanik 2005, pp. 54–57.

- 1 2 3 Baruah, Professor of Political Studies Sanjib; Baruah, Sanjib (29 June 1999). India Against Itself: Assam and the Politics of Nationality. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-8122-3491-6. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ↑ Chadha, Vivek (4 March 2005). Low Intensity Conflicts in India: An Analysis - Vivek Chadha - Google Books. SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9788132102014. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- 1 2 "The Assam narrative~II". The Statesman. 13 January 2020. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- 1 2 Barbhuiya, Atiqur Rahman (27 January 2020). Indigenous People of Barak Valley. Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-64678-800-2.

- ↑ Khalid, Saif. "'We're sons of the soil, don't call us Bangladeshis'". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ↑ India (1951). "Annual Arrival of Refugees in Assam in 1946–1951". Census of India. XII, Part I (I-A): 353 – via web.archive.org.

- ↑ http://iussp2005.princeton.edu Archived 29 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine › ...PDF The Brahmaputra valley of India can be compared only with the Indus ...

- ↑ "iussp2005". iussp2005.princeton.edu. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "Adelaide Research & Scholarship: Home". digital.library.adelaide.edu.au. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "EXCLUSIVE: BJP Govt plans to evict 70 lakh Muslims, 60 lakh Bengali Hindus through its Land Policy (2019) in Assam". SabrangIndia. 5 December 2019. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "Citizenship Amendment Act: BJP chasing ghosts in Assam; Census data shows number of Hindu immigrants may have been exaggerated". Firstpost. 18 December 2019. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "Assam Elections: Why Stakes Are High for BJP in Bengali-speaking Barak Valley". www.news18.com. 1 April 2021. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "The role of language and religion in Assam battle". Hindustan Times. 24 March 2021. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ Kalita, Kangkan (14 February 2020). "'Bengalis in Assam uncertain over Assamese people tag' | Guwahati News". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 31 December 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "20 lakh Bangladeshi Hindus to become Indians if Citizenship Bill is passed: Krishak Mukti Sangram Samiti". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "Bengali Hindu refugees in Assam's Barak Valley hope for CAB's passage in RS". Hindustan Times. 11 December 2019. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ Ghosh, Arunabha (1993). "Jharkhand Movement in West Bengal". Economic and Political Weekly. 28 (3/4): 121–127. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4399308. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Sengupta 2002, p. 98.

- ↑ Dikshit, K. R.; Dikshit, Jutta K. (2013). North-East India: Land, People and Economy. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 352. ISBN 978-94-007-7055-3. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ↑ Karmakar, Rahul (27 October 2018). "Tripura, where demand for Assam-like NRC widens gap between indigenous people and non-tribal settlers". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "When Indira Gandhi said: Refugees of all religions must go back – Watch video". www.timesnownews.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ Wolpert, Stanley A. (2000) [First published 1977]. A new history of India (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 390–1. ISBN 978-0-19-512876-5.

- ↑ Tripura Human Development Report 2007 (PDF). Government of Tripura. 2007. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ↑ "BJP eyes 2.2 m Bengali Hindus in Tripura quest". The Pioneer. Archived from the original on 14 September 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "Tripura election 2018: What prompted Bengali-majority Tripura to forgive BJP | India News". The Times of India. 4 March 2018. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "Andaman Nicobar population - a description". Population mix of Andaman and Nicobar. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "Islam in Arakan: An interpretation from the Indian perspective: History and the Present - Kaladan Press Network". www.kaladanpress.org. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Pearce, Melissa (10 July 2013). "Defining Bengali Cuisine: The Culinary Differences of West Bengal and Bangladesh". Culture Trip. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Krondl, Michael (1 August 2010). "The Sweetshops of Kolkata". Gastronomica. 10 (3): 58–65. doi:10.1525/gfc.2010.10.3.58. ISSN 1529-3262. JSTOR 10.1525/gfc.2010.10.3.58. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Sengupta 2002Ch-XII

- ↑ "Machha [ Fish Curries ] | Authentic Odia Cuisines & Recipes". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Sen 1993, p. 18.

- 1 2 Ghosh, Anjan (1981). "Review of Caste Dynamics Among the Bengali Hindus". Sociological Bulletin. 30 (1): 96–99. doi:10.1177/0038022919810109. ISSN 0038-0229. JSTOR 23619215. S2CID 220049219. Archived from the original on 15 May 2023. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ↑ Bose, Nirmal Kumar (1958). "Some Aspects of Caste in Bengal". The Journal of American Folklore. 71 (281): 397–412. doi:10.2307/538569. ISSN 0021-8715. JSTOR 538569. Archived from the original on 27 October 2023. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ↑ "Chaitanya Mahaprabhu: A relook at the saint and reformer". Telegraph India. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Sultana 2003, pp. 183–184.

- ↑ Bengali literature at the Encyclopædia Britannica. pp. 2.

- ↑ Clark, T. W. (1955). "Evolution of Hinduism in Medieval Bengali Literature: Śiva, Caṇḍī, Manasā". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 17 (3): 503–518. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00112418. ISSN 0041-977X. JSTOR 609593. S2CID 161974582. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Nambiar, Sridevi (March 2017). "A Brief History of Kalighat Paintings in Kolkata, India". Culture Trip. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ↑ Chatterjee, Partha (1975). "Bengal: Rise and Growth of a Nationality". Social Scientist. 4 (1): 67–82. doi:10.2307/3516391. ISSN 0970-0293. JSTOR 3516391.

- ↑ "Nationalism and Art in India". The Heritage Lab. 9 September 2018. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ↑ "Hinduism in Bengal and Surrounding Areas". obo. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Aquil, Raziuddin (17 January 2019). "History of a distinct culture". Frontline. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ "Studying religion". OpenLearn. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ "A documentary on India's guru-shishya parampara". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ↑ "Celebrating the 'essence of Hinduism': How 19th century Brahmo Samaj altered Bengali society". The Indian Express. 17 April 2021. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ ঘোষ, দীপঙ্কর. বারো মাসে তেরো পার্বণ. www.anandabazar.com (in Bengali). Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Ghosh, Bishwanath (22 January 2020). "In Bengal, significant hike in the number of holidays for Hindu festivals". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Durga Puja.org Archived 10 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Durga Puja festival". www.durgapuja.net. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Durga Puja at the Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ "Bengal celebrates Saraswati Puja". Outlook India. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ "Religious power in Bengal". ari.nus.edu.sg. Archived from the original on 19 November 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ McDermott 2005, p. 830.

- ↑ McCutchion, David J. (1993). Late Mediaeval Temples of Bengal: Origins and Classification. Asiatic Soc. pp. 14, 19–22. ISBN 978-93-81574-65-2.

- ↑ Norenzayan, Ara (25 August 2013). Big Gods: How Religion Transformed Cooperation and Conflict. Princeton University Press. pp. 55. ISBN 978-1-4008-4832-4.

Bibliography

- Bhattacharyya, S. K. (1987). Genocide in East Pakistan/Bangladesh: A Horror Story. A. Ghosh. ISBN 978-0-9611614-3-9.

- Chaudhuri, Rachita (2008). Buddhist Education in Ancient India. Punthi Pustak. pp. 243–345. ISBN 978-81-86791-77-6.

- Dastidar, Sachi G (2008). Empire's last casualty: Indian subcontinent's vanishing Hindu and other minorities. Kolkata: Firma KLM. ISBN 978-81-7102-151-2. OCLC 220925148.

- Ghosh, Binoy (1950). Paschimbanger Sanskriti. Press & People Republic.

- Inden, Ronald B.; Nicholas, Ralph W. (2005). Kinship in Bengali culture. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-8028-018-4.

- Kamra, A. J (2000). The prolonged partition and its pogroms. New Delhi: Voice of India. ISBN 978-81-85990-63-7. OCLC 47168311.

- Majumdar, R. C (2017) [1977]. Ancient India History. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120804357.

- McDermott, Rachel Fell (2005). "Bengali religions". In Lindsay Jones (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion: 15 Volume Set. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Detroit, Mi: MacMillan Reference USA. pp. 824–832. ISBN 0-02-865735-7.

- Mitra, Satish Chandra (2015). Jashor Khulnar Itihash. Deys Publishers.

- Pramanik, Bimal (2005). Endangered Demography: Nature and Impact of Demographic Changes in West Bengal. G.C. Modak. ISBN 978-1-4985-3742-1.

- Ray, Niharranjan (1994). History of the Bengali People: Ancient Period. Orient Longman. ISBN 978-0-86311-378-9.

- Roy, Tathagata (2002). My People, Uprooted: A Saga of the Hindus of Eastern Bengal. Kolkata: Ratna Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-85709-67-3.

- Sen, Dinesh Chandra (1993). Brihatbanga. Dey Publishers. ISBN 978-8170791867.

- Sengupta, Nitish (2002). History of the Bengali-Speaking People. UBS Publishers. ISBN 978-8174763556.

- Sultana, Jasmin (2003). Islam, Sirajul (ed.). Banglapedia: Kotalipara. Vol. 6. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 978-984-32-0581-0.

External links

Media related to Bengali Hindus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bengali Hindus at Wikimedia Commons- Bengali Hindu modern history