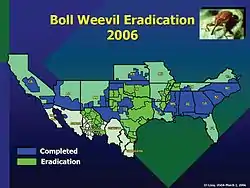

The Boll Weevil Eradication Program is a program sponsored by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) which has sought to eradicate the boll weevil in the cotton-growing areas of the United States. It's one of the world's most successful implementations of integrated pest management. The program has enabled cotton farmers to reduce their use of pesticides by between 40-100%, and increase their yields by at least 10%, since its inception in the 1970s. By the autumn of 2009, eradication was finished in all US cotton regions with the exception of less than one million acres still under treatment in Texas.[1]

History

Since its migration from Mexico in the late 19th century, the boll weevil had been the single most destructive cotton pest in the United States, and possibly the most destructive agricultural pest in the United States. The cost of its crop depredations has been estimated at $300 million per year.[2] The control measures used have included a wide range of pesticides, including calcium arsenate, DDT, toxaphene, aldrin, dieldrin, endrin, heptachlor, malathion, and parathion. In 1958, the National Cotton Council garnered the Congressional support to create the USDA Boll Weevil Research Lab.

In 1959 J. R. Brazzel and L. D. Newsom published a paper outlining the winter dormancy (diapause) behavior of the boll weevil.[3] Brazzel published the results of his first diapause control insecticide treatment trial in 1959, finding that methyl parathion treatments in the fall significantly reduced the overwintering population, especially when combined with plowing of the stalks into the ground. More sophisticated trapping and monitoring devices were developed over the next decade. Further progress was made when the male boll weevil pheromone was identified in the 1960s; the insects could be lured into traps baited with this pheromone, further reducing their reproduction, and enhancing the monitoring system.

The first full-scale eradication trial began in 1978 in southern Virginia and eastern North Carolina. After initial success, the USDA's APHIS (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service) agency established an eradication plan. The cost of the program was borne both by APHIS (30%) and by the producer (70%). Since the weevil can travel long distances quickly, it was important to implement the program on a regional basis. Expansion of the program usually required cotton producers within the area of proposed expansion to pass a referendum with at least a two-thirds majority. Some states passed legislation to help growers pay their share of program costs.

The program was extended into the southeast and southwest during the 1980s. Eradication is now complete in all cotton growing states except Texas, where problems along the Mexican border have halted the program there. Eradication was not complete in Texas as of 2022.[4]

Operation

USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) provides technical support and limited Federal funds. The state departments of agriculture provide regulatory support, and USDA’s Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Services help in disseminating program information.

Three main techniques are employed over a 3-5-year period: pheromone traps for detection, cultural practices to reduce the weevil’s food supply, and malathion treatments. During the first year, applications of malathion are made every five to seven days starting in late summer. The frequency is reduced to every 10 days during the later part of the growing season until the first frost. The cotton stalks are shredded and plowed into the ground to eliminate their use as a winter shelter. During years 2 through 5, the automatic spraying is supplemented by an intensive trapping program (one trap per 1–2 acres), and malathion applications are made only in those fields where weevils are detected. This phase begins in late spring and continues until the first killing frost. The final phase of the program involves monitoring and trapping at a density of one trap per 10 acres (40,000 m2), with spot spraying as required. The program has become more high-tech in recent years, employing GPS mapping technology and bar code readers that transmit trap data electronically.

In portions of its range, the program has been bolstered by the spread of the red imported fire ant, which attacks the larvae and pupae of the boll weevil.[5]

Impacts

At one time, cotton growers applied more than 41 percent of all insecticides in agricultural use; they regularly sprayed their cotton as many as 15 times a season. In contrast, under this program, only two applications are made by the third year, and this number may be reduced to nearly zero when the nationwide program is completed. The benefit-cost ratio is estimated by the USDA at 12:1, and the research that built the program will be used in other projects. The program may be used as a model for control of the sea lamprey infestation of the Great Lakes.[6]

The ecological benefits of the program are manifold; in addition to reducing pesticide use in the US, the fumigation of exported U.S. cotton bales with methyl bromide has also been significantly reduced. Fewer pesticide applications enable other insects to survive, including those that naturally prey on the boll weevil.

References

- ↑ Current Status of Boll Weevil Eradication Program, National Cotton Council, Fall 2009

- ↑ Boll weevil economic impacts

- ↑ Brazzel, J. R.; Newsom, L. D. (1959-08-01). "Diapause in Anthonomus grandis Boh". Journal of Economic Entomology. 52 (4): 603–611. doi:10.1093/jee/52.4.603. ISSN 1938-291X.

- ↑ "Welcome". Texas Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

- ↑ US EPA - Cotton pesticide considerations Archived 2004-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Boll weevil eradication: a model for sea lamprey control? Journal of Great Lakes Research 2003