| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

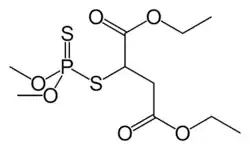

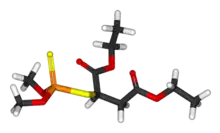

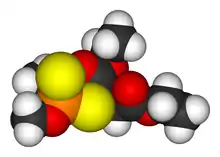

| IUPAC name

Diethyl 2-[(dimethoxyphosphorothioyl)sulfanyl]butanedioate | |

| Other names

2-(Dimethoxyphosphinothioylthio) butanedioic acid diethyl ester Malathion Carbofos Maldison Mercaptothion Ortho malathion | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.089 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C10H19O6PS2 | |

| Molar mass | 330.358021 |

| Appearance | Clear colorless liquid |

| Density | 1.23 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 2.9 °C (37.2 °F; 276.0 K) |

| Boiling point | 156 to 157 °C (313 to 315 °F; 429 to 430 K) at 0.7 mmHg |

| 145 mg/L at 20 °C[1] | |

| Solubility | Soluble in ethanol and acetone; very soluble in ethyl ether |

| log P | 2.36 (octanol/water)[2] |

| Pharmacology | |

| P03AX03 (WHO) QP53AF12 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| Flash point | 163 °C; 325 °F; 436 K (greater than)[3] |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

290 mg/kg (rat, oral) 190 mg/kg (mouse, oral) 570 mg/kg (guinea pig, oral)[4] |

LC50 (median concentration) |

84.6 mg/m3 (rat, 4 hr)[4] |

LCLo (lowest published) |

10 mg/m3 (cat, 4 hr)[4] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 15 mg/m3 [skin][3] |

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 10 mg/m3 [skin][3] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

250 mg/m3[3] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Malathion is an organophosphate insecticide which acts as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. In the USSR, it was known as carbophos, in New Zealand and Australia as maldison and in South Africa as mercaptothion.

Pesticide use

Malathion is a pesticide that is widely used in agriculture, residential landscaping, public recreation areas, and in public health pest control programs such as mosquito eradication.[5] In the US, it is the most commonly used organophosphate insecticide.[6]

A malathion mixture with corn syrup was used in the 1980s in Australia and California to combat the Mediterranean fruit fly.[7] In Canada and the US starting in the early 2000s, malathion was sprayed in many cities to combat west Nile virus.[8] Malathion was used over the last couple of decades on a regular basis during summer months to kill mosquitoes, but homeowners were allowed an exemption for their properties if they chose..

Mechanism of action

Malathion is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, a diverse family of chemicals. Upon uptake into the target organism, it binds irreversibly to the serine residue in the active catalytic site of the cholinesterase enzyme. The resultant phosphoester group is strongly bound to the cholinesterase, and irreversibly deactivates the enzyme which leads to rapid build-up of acetylcholine at the synapse.[9]

Production method

Malathion is produced by the addition of dimethyl dithiophosphoric acid to diethyl maleate or diethyl fumarate. The compound is chiral but is used as a racemate.

Medical use

Malathion in low doses (0.5% preparations) is used as a treatment for:

- Head lice and body lice. Malathion is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of pediculosis.[10][11] It is claimed to effectively kill both the eggs and the adult lice, but in fact has been shown in UK studies to be only 36% effective on head lice, and less so on their eggs.[12] This low efficiency was noted when malathion was applied to lice found on schoolchildren in the Bristol area in the UK, and it is assumed to be caused by the lice having developed resistance against malathion.

- Scabies[13]

Preparations include Derbac-M, Prioderm, Quellada-M[14] and Ovide.[15]

Safety

General

Malathion is of low toxicity. In arthropods it is metabolized into malaoxon[16] which is 61x more toxic,[17] being a more potent inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase.[18] According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, no reliable information is available on adverse health effects of chronic exposure.[19]

In 1981, Malathion was sprayed over a 1,400 sq mi (3,600 km2) area to control an outbreak of Mediterranean fruit flies in California. In order to demonstrate the chemical's safety, B. T. Collins, director of the California Conservation Corps, publicly swallowed a mouthful of dilute malathion solution.[20]

Carcinogenicity

Malathion is classified by the IARC as probable carcinogen (group 2A). Malathion is classified by US EPA as having "suggestive evidence of carcinogenicity".[17] This classification was based on the occurrence of liver tumors at excessive doses in mice and female rats and the presence of rare oral and nasal tumors in rats that occurred following exposure to very large doses. Exposure to organophosphates is associated with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Malathion used as a fumigant was not associated with increased cancer risk. Between 1993 and 1997, as part of the Agricultural Health Study, no clear association between malathion exposure and cancer was reported.[21]

Amphibians

Malathion is toxic to leopard frog tadpoles.[22]

Risks

General

Malathion is of low toxicity; however, absorption or ingestion into the human body readily results in its metabolism to malaoxon, which is substantially more toxic.[23] In studies of the effects of long-term exposure to oral ingestion of malaoxon in rats, malaoxon has been shown to be 61 times more toxic than malathion,[23] and malaoxon is 1,000 times more potent than malathion in terms of its acetylcholinesterase inhibition.[18] Indoor spillage of malathion can thus be more poisonous than expected, as malathion breaks down in a confined space into the more toxic malaoxon. It is cleared from the body quickly, in three to five days.[24]

Resistance

Because it is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, this resistance is a type of AChEI resistance.[16] Malathion resistance is thought to always be due to either increased carboxylesterase concentrations or altered acetylcholinesterases.[16] COE because it metabolizes malathion but into non-malaoxon products, altered AChEs because we mean specifically those altered to be less sensitive to malathion and malaoxon.[16]

See also

References

- ↑ Tomlin, C.D.S. (ed.). The Pesticide Manual - World Compendium, 11th ed., British Crop Protection Council, Surrey, England 1997, p. 755

- ↑ Hansch, C., Leo, A., D. Hoekman. Exploring QSAR - Hydrophobic, Electronic, and Steric Constants. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society., 1995., p. 80

- 1 2 3 4 NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0375". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- 1 2 3 "Malathion". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ Malathion for mosquito control, US EPA

- ↑ Bonner MR, Coble J, Blair A, et al. (2007). "Malathion Exposure and the Incidence of Cancer in the Agricultural Health Study". American Journal of Epidemiology. 166 (9): 1023–1034. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm182. PMID 17720683.

- ↑ Edwards JW, Lee SG, Heath LM, Pisaniello DL (2007). "Worker exposure and a risk assessment of malathion and fenthion used in the control of Mediterranean fruit fly in South Australia". Environ. Res. 103 (1): 38–45. Bibcode:2007ER....103...38E. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2006.06.001. PMID 16914134.

- ↑ Shapiro, H.; Micucci, S. (2003-05-27). "Pesticide use for West Nile virus". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 168 (11): 1427–1430. PMC 155959. PMID 12771072.

An extensive re-evaluation of malathion was completed by the US Environmental Protection Agency in 2000. The PMRA has also re-evaluated malathion and approved its use as a mosquito adulticide.

- ↑ Colovic, Mirjana B.; Krstic, Danijela Z.; Lazarevic-Pasti, Tamara D.; Bondzic, Aleksandra M.; Vasic, Vesna M. (2013). "Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors: Pharmacology and Toxicology". Current Neuropharmacology. 11 (3): 315–335. doi:10.2174/1570159X11311030006. PMC 3648782. PMID 24179466.

- ↑ "Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pediculosis capitis (head lice) in children and adults 2008". National Guideline Clearinghouse. Archived from the original on 2013-02-26. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- ↑ Amy J. McMichael; Maria K. Hordinsky (2008). Hair and Scalp Diseases: Medical, Surgical, and Cosmetic Treatments. Informa Health Care. pp. 289–. ISBN 978-1-57444-822-1. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ↑ Downs AM, Stafford KA, Harvey I, Coles GC (1999). "Evidence for double resistance to permethrin and malathion in head lice". Br. J. Dermatol. 141 (3): 508–11. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03046.x. PMID 10583056. S2CID 25087526.

- ↑ Julia A. McMillan; Ralph D. Feigin; Catherine DeAngelis; M. Douglas Jones (1 April 2006). Oski's pediatrics: principles & practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-7817-3894-1. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ↑ British National Formulary 54th Ed. Sept 2007. ISBN 978-0-85369-736-7. ISSN 0260-535X

- ↑ "AHFS Drug Information". American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 13 January 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Lebwohl, Mark; Clark, Lily; Levitt, Jacob (2007). "Therapy for Head Lice Based on Life Cycle, Resistance, and Safety Considerations". Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). 119 (5): 965–974. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-3087. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 17473098. S2CID 30758188.

- 1 2 Keigwin Jr RP (May 2009). "Reregistration Eligibility Decision for Malathion (Revised)" (PDF). US Environmental Protection Agency - Prevention, Pesticides and Toxic Substances EPA 738-R-06-030 Journal: 9.

- 1 2 Rodriguez, O. P.; Muth, G. W.; Berkman, C. E.; Kim, K.; Thompson, C. M. (February 1997). "Inhibition of various cholinesterases with the enantiomers of malaoxon". Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 58 (2): 171–176. doi:10.1007/s001289900316. ISSN 0007-4861. PMID 8975790. S2CID 29903092.

- ↑ "US Department of Health and Human Services: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry - Medical Management Guidelines for Malathion". Archived from the original on October 21, 2002. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ↑ Bonfante, Jordan (1990-01-08). "Medfly Madness". TIME. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- ↑ "Active Ingredient Fact Sheets". npic.orst.edu.

- ↑ "Low Concentrations Of Pesticides Can Become Toxic Mixture For Amphibians". Science Daily. November 18, 2008. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- 1 2 Edwards D (July 2006). "Reregistration Eligibility Decision for Malathion" (PDF). US Environmental Protection Agency - Prevention, Pesticides and Toxic Substances EPA 738-R-06-030 Journal: 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-21.

- ↑ Maugh II, Thomas H. (16 May 2010). "Study links pesticide to ADHD in children". Los Angeles Times.

External links

- Malathion Technical Fact Sheet - National Pesticide Information Center

- Malathion General Fact Sheet - National Pesticide Information Center

- Malathion Pesticide Information Profile - Extension Toxicology Network

- ATSDR ToxFAQs

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Re-evaluation of Malathion by the Pest Management Regulatory Agency of Canada

- Malathion in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)