| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Colombo |

| Namesake | Christopher Columbus |

| Launched | 1865 |

| Commissioned | 4 July 1866 |

| Decommissioned | 4 February 1875 |

| Fate | Scrapped |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Cabral-class ironclad |

| Displacement | 1,069 metric tons (1,052 long tons) |

| Length | 48.76 m (160 ft 0 in) |

| Beam | 10.6 m (34 ft 9 in) |

| Draft | 3.23 m (10.6 ft) |

| Installed power | 750 ihp (560 kW) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts, 2 steam engines |

| Speed | 10.5 knots (19.4 km/h; 12.1 mph) |

| Complement | 125 officers and men |

| Armament | 8 × rifled 70 and 68-pounder guns |

| Armor | |

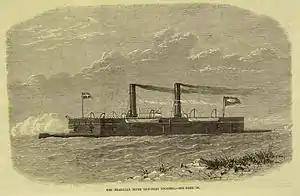

The Brazilian ironclad Colombo was a Cabral-class armored corvette-type ironclad operated by the Imperial Brazilian Navy between 1866 and 1875. The vessel was built in the shipyard in Greenwich, England, by the British company J. and G. Rennie, along with her sister ship Cabral. It was launched in 1865 being commissioned on 4 July 1866. The battleship was entirely made of iron, displacing 1,069 tons. It had two steam engines that developed up to 750 HP of power, propelling the vessel at about 20 km/h. Its structure comprised a double casemate with eight gunports. The Brazilian navy had great difficulties with this ship, which was hard to navigate and, due to the casemate's model, had an unprotected section, which was vulnerable to diving projectiles.

A few months after its arrival in Brazil, Colombo was sent to the front in the Paraguayan War. The first obstacle faced by the ship was the Fortress of Curupayty, which, together with several other ships of the imperial fleet, it bombed heavily on 2 February 1867. On 15 August, Colombo successfully forced the passage of this fort, a maneuver that lasted about two hours. In July 1868, Colombo participated in the bombardment of the Fortress of Humaitá. On 5 October, Colombo carried out an aggressive reconnaissance of the Angostura Fortress.

In the last years of the war, the ship was no longer in needed and returned to Rio de Janeiro, where it underwent repair works. In 1873, it was assigned to the third naval division, with the mission of patrolling the Brazilian coast between Mossoró, in Rio Grande do Norte, to the limits with French Guiana. The Brazilian navy decommissioned it on 4 February 1875.

Design and description

Colombo was built in Greenwich, England, by the company J. and G. Rennie, in 1865. On 4 July 1866, it was incorporated into the Imperial Brazilian Navy, undergoing an armament display on 7 July, when it received the badge number 13. It was named Colombo in honor of Genoese navigator Christopher Columbus. Colombo was designated as an ironclad corvette and belonged to the Cabral-class.[1]

The ship was iron plated, had a displacement of 1,069 tons, measured 48.76 m in length, 10.6 m in beam, 3.05 m in depth and 3.23 m in draft. Its machines consisted of two steam engines that developed 240 hp, according to the Brazilian navy, or 750 hp, according to naval writer Gardiner, which drove two shafts and propelled the ship to a maximum speed of 10.5 knots (19.44 km/h). Colombo had two chimneys, a rudder, a small mast for signals, a casemate and was armed with eight 70 and 68-pounder Withworth cannons. Its crew consisted of 125 enlisted men and officers. The navy considered it a ship with poor nautical qualities, and even dangerous. Added to this was the fact that the ship was built with a system of double casemates that left, amidships, an unprotected area over the boilers, vulnerable to diving shots. Colombo arrived in Brazil on 25 June 1866.[1][2][3]

History

Actions in Curupayty

In August 1866, Colombo was sent to the front in the Paraguayan War, and docked on September 2 at Desterro, present-day Florianópolis. On 2 February 1867, already in Paraguayan territory, Colombo and other ships bombarded the Fortress of Curupayty, which was on the banks of the Paraguay River.[4] At the time, the ironclad was part of the fleet formed by the ships Bahia, Barroso, Cabral (its sister ship), Herval, Mariz e Barros, Silvado and Tamandaré, the corvettes Parnaíba and Beberibe, the gunboat Forte de Coimbra and two artillery barges, under the command of vice admiral Joaquim José Inacio.[5]

This fleet bombarded the fortress together with the battery of the Forte de Curuzu, already taken by the Brazilians, the snipers of the 48th Battalion of Volunteers of the Homeland and with the fleet of the chief Elisiário dos Santos, which included the gunboats Araguari and Iguatemi, Lindóia steamer, Pedro Afonso bomber, Mercedes barge and João das Botas launch. A total of 874 bombs were fired on the fort, killing countless Paraguayans, in addition to seriously injuring its commander, General Díaz. On the Brazilian side, there were about 14 casualties, including the death of the commander of Silvado.[1][5]

The imperial navy was studying a way to force the passage of this fortress, but considered the feat practically impossible.[6] Curupayty was a set of fortifications and trenches that formed part of the defensive complex of Humaitá.[7] It had 35 artillery pieces aimed at the river,[7] and included the 80-caliber El Cristiano cannon,[8] one of the largest made in the 19th century.[9] Still, the navy chose to force the passage, choosing the 15th of August for the action. Before that, however, the fortress was bombarded on 29 May and 5 August.[5]

On 15 August, Colombo forced the passage of Curupayty, towing the barge Cuevas. According to a Brazilian historian, “Curupaiti resisted with all the powers of despair, filling the air with a hideous roar, and not being able to hold back the gallant ships that followed their destiny with strings of bullets. Not even the projectiles of rifles saw fit to dispense with. They were thrown back with huge bombs and shallow 68 bullets, which made a dent, few of which actually did damage.” Columbus, battleship Brazil, monitor Lima Barros and seven other battleships from the fleet that had bombed the fortress on February 2, took about two hours to cross the pass, with little damage to Columbus, who claimed to have received only one impact.[4][5][10][11][12]

Actions in Humaitá, Angostura and Manduvirá

The allied naval high command decided to transpose Humaitá again with the objective of strengthening the position of the ships that had already passed the fortress on 19 February, and to increase the naval force that would act in the Tebicuarí region, where another Paraguayan fortification was already known.[13] To carry out this passage, three battleships were designated, Cabral, Silvado and Piauí, who would force the pass, and two who would act in their protection, Lima Barros and Brasil.[14] Colombo, Herval, Lima Barros and Mariz e Barros would act as support fire. The transposition took place in the early hours of 21 July 1868, with some problems caused by Cabral's poor navigability. After the passage, Humaitá was abandoned by the Paraguayans days later.[15]

During October 1868, the ironclads Tamandaré, Bahia, Silvado, Barroso, Brasil, Alagoas, Lima Barros and Rio Grande, in that order, forced the passage of Angostura, a fortress on the Paraguay River heavily defended by several batteries. On the 5th, Colombo, under the command of Marques Guimarães, carried out an aggressive reconnaissance of the batteries that protected the fort. On the 28th, Cabral and Piauí began a long and strong bombardment of these batteries. On 19 November, the fort was again violently bombarded by the same squadron with the support of Colombo, Herval and Mariz e Barros, with captain Mamede Simões directing the fire.[16] A week later, Brasil, Cabral, Piauí and the steamer Triunfo made the crossing of Angostura, a fort that would continue to be bombarded throughout December, until its complete surrender on the 30th.[17][18]

On 16 April 1869, Colombo was assigned by the new Brazilian naval commander, chief of squadron Elisiário Antônio dos Santos, to compose the squadron that would carry out the second expedition on the Manduvirá River with the goal of chasing the Paraguayan ships that were there. The ironclad's mission, together with the corvette Belmonte, was to block the river. The second expedition ended on the 30th.[19] On 17 May, Colombo served as a transport ship for the troops of general José Antônio Correia da Câmara, who was in pursuit of Solano López, to the village of Rosario.[4]

Last years

Since the conquest of Asunción, on 1 January 1869, the already worn out large battleships, such as Colombo, were no longer as useful in the conflict, with naval combats taking place, from then on, in small, very narrow streams, only Tamandaré and the six Pará-class monitors remained in Asunción. Colombo still participated in some missions earlier that year, however, this and other battleships were recalled to Rio de Janeiro, where they underwent major repair works. In 1870, the imperial naval command began to distribute the battleships to the various naval districts for the defense of ports in Brazil.[4][19][20] This year, in a volley of gunfire, one of the cannons exploded and killed an Imperial sailor and wounded another.[4]

In the first district, which ran from the extreme south of Brazil to the border between Rio de Janeiro and Espírito Santo, the ironclads Brasil, Lima Barros, Silvado and Bahia were allocated. In the second, which started on the limits of the first until the city of Mossoró, in Rio Grande do Norte, the Herval and Mariz e Barros were anchored. Finally, in mid-1873, Colombo and her sister ship Cabral were assigned to the third district, which ran from Mossoró to French Guiana.[21]

By Notice of 20 February 1874, Colombo was given the display of half armament; on the other hand, on 5 January 1875, the ship underwent a disarmament show to go into repairs at the Arsenal of Rio de Janeiro. On 4 February 1875, the navy decommissioned the ironclad, with the hull being handed over to be scrapped on 26 June 1880.[4]

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 Marinha do Brasil-A, p. 1.

- ↑ Lyon 1979, p. 406.

- ↑ Martini 2014, pp. 127–128.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Marinha do Brasil-A, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 Donato 1996, p. 276.

- ↑ Maestri 2017, p. 357.

- 1 2 Fragoso 1956, p. 212.

- ↑ Donato 1996, p. 277.

- ↑ Santos 2018, p. 5.

- ↑ Marinha do Brasil-B, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Rio Branco 2012, p. 463.

- ↑ Costa 1870, p. 305.

- ↑ Barros 2018, p. 48.

- ↑ Barros 2018, p. 50.

- ↑ Donato 1996, p. 307.

- ↑ Donato 1996, pp. 185–186.

- ↑ Marinha do Brasil-B, p. 2.

- ↑ Donato 1996, pp. 186–187.

- 1 2 Barros 2016, pp. 78, 79, 84.

- ↑ Martini 2014, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Martini 2014, p. 149.

Bibliography

- Barros, Aldeir Isael Faxina (2016). "A Marinha Imperial Brasileira no Manduvirá" (PDF). Revista Marítima Brasileira. Vol. 136, no. 4/06. ISSN 0034-9860.

- Barros, Aldeir Isael Faxina (2018). "A Segunda Passagem de Humaitá" (PDF). Navigator. 14 (27): 45–57. ISSN 0100-1248. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-02-12. Retrieved 2022-09-18.

- Costa, Francisco Felix Pereira da (1870). Historia da guerra do Brasil contra as Republicas do Uruguay e Paraguay. Vol. 3. Rio de Janeiro: Livraria de A.G. Guimãraes & C.

- Donato, Hernâni (1996). Dicionário das Batalhas Brasileiras (2 ed.). São Paulo: Instituição Brasileira de Difusão Cultural. ISBN 8534800340. OCLC 36768251.

- Fragoso, Tasso (1956). História da Guerra entre a Tríplice Aliança e o Paraguai. Vol. III (2nd ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Livraria Freitas Bastos S.A.

- Lyon, Hugh (1979). "Brazil". In Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Maestri, Mário (2017). Guerra Sem Fim (1 ed.). Brasil: Clube de Autores. ISBN 978-8567542164.

- Marinha do Brasil-A. "Colombo Corveta" (PDF). Diretoria do Patrimônio Histórico e Documentação da Marinha.

- Marinha do Brasil-B. "Cabral Corveta" (PDF). Diretoria do Patrimônio Histórico e Documentação da Marinha.

- Martini, Fernando Ribas de (2014). "Construir navios é preciso, persistir não é preciso: a construção naval militar no Brasil entre 1850 e 1910, na esteira da Revolução Industrial" (PDF). Biblioteca Digital USP. Universidade de São Paulo. doi:10.11606/D.8.2014.tde-23012015-103524.

- Rio Branco, Barão do (2012). Obras do Barão do Rio Branco: Efemérides Brasileiras. Brasília: Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão. ISBN 978-85-7631-357-1. OCLC 842885255.

- Santos, Wellington Corlet dos (2018). "A questão do canhão El Cristiano: Reflexões" (PDF). Ahimtb/Rs (264).