Burkina Faso | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Unité–Progrès–Justice" (French) ("Unity–Progress–Justice") | |

| Anthem: "Une Seule Nuit" / "Ditanyè" (French) ("One Single Night" / "Hymn of Victory") | |

.svg.png.webp)

| |

| Capital and largest city | Ouagadougou 12°22′N 1°32′W / 12.367°N 1.533°W |

| Recognised national languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2010 est.)[1] | |

| Demonym(s) | Burkinabè |

| Government | Unitary republic under a military junta[2][3][4] |

| Ibrahim Traoré | |

| Apollinaire Joachim Kyélem de Tambèla | |

| Legislature | Transitional Legislative Assembly |

| History | |

• Republic of Upper Volta proclaimed | 11 December 1958 |

• Independence from France | 5 August 1960 |

| 3 January 1966 | |

| 28 October – 3 November 2014 | |

| 23–24 January 2022 | |

| 30 September 2022 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 274,223[5] km2 (105,878 sq mi) (74th) |

• Water (%) | 0.146% |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 22,489,126[5] (60th) |

• Density | 64/km2 (165.8/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2020) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | low · 184th |

| Currency | West African CFA franc[9] (XOF) |

| Time zone | UTC+00:00 |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +226 |

| ISO 3166 code | BF |

| Internet TLD | .bf |

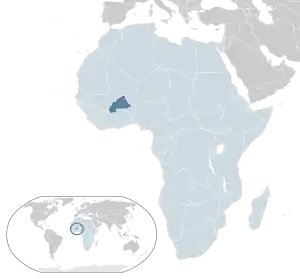

Burkina Faso (UK: /bərˌkiːnə ˈfæsoʊ/ bər-KEE-nə FASS-oh, US: /-ˈfɑːsoʊ/ ⓘ -FAH-soh;[10] French: [buʁkina faso], Mossi: [bùɾkĩná fà.só], Fula: 𞤄𞤵𞤪𞤳𞤭𞤲𞤢 𞤊𞤢𞤧𞤮) is a landlocked country in West Africa with an area of 274,223 km2 (105,878 sq mi),[5] bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana to the south, and Ivory Coast to the southwest. As of 2021, the country had an estimated population of 20,321,378.[11] Previously called Republic of Upper Volta (1958–1984), it was renamed Burkina Faso by President Thomas Sankara. Its citizens are known as Burkinabè (/bɜːrˈkiːnəbeɪ/ bur-KEE-nə-bay), and its capital and largest city is Ouagadougou. Its name is often translated into English as the "Land of Honest Men".[12]

The largest ethnic group in Burkina Faso is the Mossi people, who settled the area in the 11th and 13th centuries. They established powerful kingdoms such as the Ouagadougou, Tenkodogo, and Yatenga. In 1896, it was colonized by the French as part of French West Africa; in 1958, Upper Volta became a self-governing colony within the French Community. In 1960, it gained full independence with Maurice Yaméogo as president. Since it gained its independence, the country was subject to instability, droughts, famines and corruption. Various coups have also taken place in the country, in 1966, 1980, 1982, 1983, 1987, and twice in 2022, in January and September, as well as an attempt in 1989 and another in 2015.

Thomas Sankara came to power following a successful coup in 1982. As president, Sankara embarked on a series of ambitious socioeconomic reforms which included a nationwide literacy campaign, land redistribution to peasants, providing vaccinations to over 2 million children, railway and road construction, equalized access to education, and the outlawing of female genital mutilation, forced marriages, and polygamy. He served as the country's president until 1987 when he was deposed and assassinated in a coup led by Blaise Compaoré, who became president and ruled the country until his removal on 31 October 2014.

Burkina Faso has been severely affected by the rise of Islamist terrorism in the Sahel since the mid-2010s. Several militias, partly allied with the Islamic State (IS) or al-Qaeda, operate in Burkina Faso and across the border in Mali and Niger. More than one million of the country's 21 million inhabitants are internally displaced persons. Burkina Faso's military seized power in a coup d'état on 23–24 January 2022, overthrowing President Roch Marc Kaboré. On 31 January, the military junta restored the constitution and appointed Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba as interim president, who was himself overthrown in a second coup on 30 September and replaced by military captain Ibrahim Traoré.[13]

Burkina Faso is one of the least developed countries in the world, with a GDP of $16.226 billion. Approximately 63.8 percent of its population practices Islam, while 26.3 percent practice Christianity.[14] The country's official language of government and business was formerly French; French was relegated to a "working language" by a bill of December 2023 which awaits ratification by the legislative assembly.[15] There are 60 indigenous languages officially recognized by the Burkinabè government, with the most common language, Mooré, spoken by over half the population.[16][17] The country has a strong culture and is geographically biodiverse, with plentiful reserves of gold, manganese, copper and limestone. Burkinabè art has a rich and long history, and is globally renowned for its orthodox style.[18] The country is governed as a semi-presidential republic with executive, legislative and judicial powers. Burkina Faso is a member of the United Nations, La Francophonie and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. It is currently suspended from ECOWAS and the African Union.

Etymology

Formerly the Republic of Upper Volta, the country was renamed "Burkina Faso" on 4 August 1984 by then-President Thomas Sankara. The words "Burkina" and "Faso" stem from different languages spoken in the country: "Burkina" comes from Mooré and means "upright", showing how the people are proud of their integrity, while "Faso" comes from the Dioula language (as written in N'Ko: ߝߊ߬ߛߏ߫ faso) and means "fatherland" (literally, "father's house"). The "-bè" suffix added onto "Burkina" to form the demonym "Burkinabè" comes from the Fula language and means "women or men".[19] The CIA summarizes the etymology as "land of the honest (incorruptible) men".[20]

The French colony of Upper Volta was named for its location on the upper courses of the Volta River (the Black, Red and White Volta).[21]

History

Early history

The northwestern part of present-day Burkina Faso was populated by hunter-gatherers from 14,000 BCE to 5000 BCE. Their tools, including scrapers, chisels and arrowheads, were discovered in 1973 through archaeological excavations.[22] Agricultural settlements were established between 3600 and 2600 BCE.[22] The Bura culture was an Iron-Age civilization centred in the southwest portion of modern-day Niger and in the southeast part of contemporary Burkina Faso.[23] Iron industry, in smelting and forging for tools and weapons, had developed in Sub-Saharan Africa by 1200 BCE.[24][25] To date, the oldest evidence of iron smelting found in Burkina Faso dates from 800 to 700 BC and form part of the Ancient Ferrous Metallurgy World Heritage Site.[26] From the 3rd to the 13th centuries CE, the Iron Age Bura culture existed in the territory of present-day southeastern Burkina Faso and southwestern Niger. Various ethnic groups of present-day Burkina Faso, such as the Mossi, Fula and Dioula, arrived in successive waves between the 8th and 15th centuries. From the 11th century, the Mossi people established several separate kingdoms.

8th century to 18th century

There is debate about the exact dates when Burkina Faso's many ethnic groups arrived to the area. The Proto-Mossi arrived in the far Eastern part of what is today Burkina Faso sometime between the 8th and 11th centuries,[27] the Samo arrived around the 15th century,[28] the Dogon lived in Burkina Faso's north and northwest regions until sometime in the 15th or 16th centuries[29] and many of the other ethnic groups that make up the country's population arrived in the region during this time.

During the Middle Ages, the Mossi established several separate kingdoms including those of Tenkodogo, Yatenga, Zandoma, and Ouagadougou.[30] Sometime between 1328 and 1338 Mossi warriors raided Timbuktu but the Mossi were defeated by Sonni Ali of Songhai at the Battle of Kobi in Mali in 1483.[31]

During the early 16th century the Songhai conducted many slave raids into what is today Burkina Faso.[28] During the 18th century the Gwiriko Empire was established at Bobo Dioulasso and ethnic groups such as the Dyan, Lobi, and Birifor settled along the Black Volta.[32]

From colony to independence (1890s–1958)

Starting in the early 1890s during the European Scramble for Africa, a series of European military officers made attempts to claim parts of what is today Burkina Faso. At times these colonialists and their armies fought the local peoples; at times they forged alliances with them and made treaties. The colonialist officers and their home governments also made treaties among themselves. The territory of Burkina Faso was invaded by France, becoming a French protectorate in 1896.[33]

The eastern and western regions, where a standoff against the forces of the powerful ruler Samori Ture complicated the situation, came under French occupation in 1897. By 1898, the majority of the territory corresponding to Burkina Faso was nominally conquered; however, French control of many parts remained uncertain.[22]

The Franco-British Convention of 14 June 1898 created the country's modern borders. In the French territory, a war of conquest against local communities and political powers continued for about five years. In 1904, the largely pacified territories of the Volta basin were integrated into the Upper Senegal and Niger colony of French West Africa as part of the reorganization of the French West African colonial empire. The colony had its capital in Bamako.

The language of colonial administration and schooling became French. The public education system started from humble origins. Advanced education was provided for many years during the colonial period in Dakar.

The indigenous population was highly discriminated against. For example, African children were not allowed to ride bicycles or pick fruit from trees, "privileges" reserved for the children of colonists. Violating these regulations could land parents in jail.[34]

Draftees from the territory participated in the European fronts of World War I in the battalions of the Senegalese Rifles. Between 1915 and 1916, the districts in the western part of what is now Burkina Faso and the bordering eastern fringe of Mali became the stage of one of the most important armed oppositions to colonial government: the Volta-Bani War.[35]

The French government finally suppressed the movement but only after suffering defeats. It also had to organize its largest expeditionary force of its colonial history to send into the country to suppress the insurrection. Armed opposition wracked the Sahelian north when the Tuareg and allied groups of the Dori region ended their truce with the government.

French Upper Volta was established on 1 March 1919. The French feared a recurrence of armed uprising and had related economic considerations. To bolster its administration, the colonial government separated the present territory of Burkina Faso from Upper Senegal and Niger.

The new colony was named Haute Volta for its location on the upper courses of the Volta River (the Black, Red and White Volta), and François Charles Alexis Édouard Hesling became its first governor. Hesling initiated an ambitious road-making program to improve infrastructure and promoted the growth of cotton for export. The cotton policy – based on coercion – failed, and revenue generated by the colony stagnated. The colony was dismantled on 5 September 1932, being split between the French colonies of Ivory Coast, French Sudan and Niger. Ivory Coast received the largest share, which contained most of the population as well as the cities of Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso.

France reversed this change during the period of intense anti-colonial agitation that followed the end of World War II. On 4 September 1947, it revived the colony of Upper Volta, with its previous boundaries, as a part of the French Union. The French designated its colonies as departments of metropolitan France on the European continent.

On 11 December 1958 the colony achieved self-government as the Republic of Upper Volta; it joined the Franco-African Community. A revision in the organization of French Overseas Territories had begun with the passage of the Basic Law (Loi Cadre) of 23 July 1956. This act was followed by reorganization measures approved by the French parliament early in 1957 to ensure a large degree of self-government for individual territories. Upper Volta became an autonomous republic in the French community on 11 December 1958. Full independence from France was received in 1960.[36]

Upper Volta (1958–1984)

The Republic of Upper Volta (French: République de Haute-Volta) was established on 11 December 1958 as a self-governing colony within the French Community. The name Upper Volta related to the nation's location along the upper reaches of the Volta River. The river's three tributaries are called the Black, White and Red Volta. These were expressed in the three colors of the former national flag.

Before attaining autonomy, it had been French Upper Volta and part of the French Union. On 5 August 1960, it attained full independence from France. The first president, Maurice Yaméogo, was the leader of the Voltaic Democratic Union (UDV). The 1960 constitution provided for election by universal suffrage of a president and a national assembly for five-year terms. Soon after coming to power, Yaméogo banned all political parties other than the UDV. The government lasted until 1966. After much unrest, including mass demonstrations and strikes by students, labor unions, and civil servants, the military intervened.

Lamizana's rule and multiple coups

The 1966 military coup deposed Yaméogo, suspended the constitution, dissolved the National Assembly, and placed Lt. Col. Sangoulé Lamizana at the head of a government of senior army officers. The army remained in power for four years. On 14 June 1976, the Voltans ratified a new constitution that established a four-year transition period toward complete civilian rule. Lamizana remained in power throughout the 1970s as president of military or mixed civil-military governments. Lamizana's rule coincided with the beginning of the Sahel drought and famine which had a devastating impact on Upper Volta and neighboring countries. After conflict over the 1976 constitution, a new constitution was written and approved in 1977. Lamizana was re-elected by open elections in 1978.

Lamizana's government faced problems with the country's traditionally powerful trade unions, and on 25 November 1980, Col. Saye Zerbo overthrew President Lamizana in a bloodless coup. Colonel Zerbo established the Military Committee of Recovery for National Progress as the supreme governmental authority, thus eradicating the 1977 constitution.

Colonel Zerbo also encountered resistance from trade unions and was overthrown two years later by Maj. Dr. Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo and the Council of Popular Salvation (CSP) in the 1982 Upper Voltan coup d'état. The CSP continued to ban political parties and organizations, yet promised a transition to civilian rule and a new constitution.[37][38]

1983 coup d'état

Infighting developed between the right and left factions of the CSP. The leader of the leftists, Capt. Thomas Sankara, was appointed prime minister in January 1983, but was subsequently arrested. Efforts to free him, directed by Capt. Blaise Compaoré, resulted in a military coup d'état on 4 August 1983.

The coup brought Sankara to power and his government began to implement a series of revolutionary programs which included mass-vaccinations, infrastructure improvements, the expansion of women's rights, encouragement of domestic agricultural consumption, and anti-desertification projects.[39]

Burkina Faso (since 1984)

On 2 August 1984, on President Sankara's initiative, the country's name changed from "Upper Volta" to "Burkina Faso", or land of the honest men; (the literal translation is land of the upright men.)[40][41][42][43] The presidential decree was confirmed by the National Assembly on 4 August. The demonym for people of Burkina Faso, "Burkinabè", includes expatriates or descendants of people of Burkinabè origin.

Sankara's government comprised the National Council for the Revolution (CNR – French: Conseil national révolutionnaire), with Sankara as its president, and established popular Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs). The Pioneers of the Revolution youth programme was also established.

Sankara launched an ambitious socioeconomic programme for change, one of the largest ever undertaken on the African continent.[39] His foreign policies centred on anti-imperialism, with his government rejecting all foreign aid, pushing for odious debt reduction, nationalising all land and mineral wealth and averting the power and influence of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. His domestic policies included a nationwide literacy campaign, land redistribution to peasants, railway and road construction and the outlawing of female genital mutilation, forced marriages and polygamy.[39][44]

Sankara pushed for agrarian self-sufficiency and promoted public health by vaccinating 2,500,000 children against meningitis, yellow fever, and measles.[44] His national agenda also included planting over 10,000,000 trees to halt the growing desertification of the Sahel. Sankara called on every village to build a medical dispensary and had over 350 communities build schools with their own labour.[39][45]

In the 1980s, when ecological awareness was still very low, Thomas Sankara was one of the few African leaders to consider environmental protection a priority. He engaged in three major battles: against bush fires "which will be considered as crimes and will be punished as such"; against cattle roaming "which infringes on the rights of peoples because unattended animals destroy nature"; and against the anarchic cutting of firewood "whose profession will have to be organized and regulated". As part of a development program involving a large part of the population, ten million trees were planted in Burkina Faso in fifteen months during the revolution. To face the advancing desert and recurrent droughts, Thomas Sankara also proposed the planting of wooded strips of about fifty kilometers, crossing the country from east to west. He then thought of extending this vegetation belt to other countries. Cereal production, close to 1.1 billion tons before 1983, was predicted to rise to 1.6 billion tons in 1987. Jean Ziegler, former UN special rapporteur for the right to food, said that the country "had become food self-sufficient."[46]

Compaoré presidency

On 15 October 1987, Sankara, along with twelve other officials, was assassinated in a coup d'état organized by Blaise Compaoré, Sankara's former colleague, who would go on to serve as Burkina Faso's president from October 1987 until October 2014.[47] After the coup and although Sankara was known to be dead, some CDRs mounted an armed resistance to the army for several days. A majority of Burkinabè citizens hold that France's foreign ministry, the Quai d'Orsay, was behind Compaoré in organizing the coup. There is some evidence for France's support of the coup.[48]

Compaoré gave as one of the reasons for the coup the deterioration in relations with neighbouring countries.[49] Compaoré argued that Sankara had jeopardised foreign relations with the former colonial power (France) and with neighbouring Ivory Coast.[50] Following the coup Compaoré immediately reversed the nationalizations, overturned nearly all of Sankara's policies, returned the country back into the IMF fold, and ultimately spurned most of Sankara's legacy. Following an alleged coup-attempt in 1989, Compaoré introduced limited democratic reforms in 1990. Under the new (1991) constitution, Compaoré was re-elected without opposition in December 1991. In 1998 Compaoré won election in a landslide. In 2004, 13 people were tried for plotting a coup against President Compaoré and the coup's alleged mastermind was sentenced to life imprisonment.[51] As of 2014, Burkina Faso remained one of the least-developed countries in the world.[52]

In 2000, the constitution was amended to reduce the presidential term to five years and set term limits to two, preventing successive re-election. The amendment took effect during the 2005 elections. If passed beforehand, it would have prevented Compaoré from being reelected. Other presidential candidates challenged the election results. But in October 2005, the constitutional council ruled that, because Compaoré was the sitting president in 2000, the amendment would not apply to him until the end of his second term in office. This cleared the way for his candidacy in the 2005 election. On 13 November 2005, Compaoré was reelected in a landslide, because of a divided political opposition.

In the 2010 presidential election, President Compaoré was re-elected. Only 1.6 million Burkinabè voted, out of a total population 10 times that size. In February 2011, the death of a schoolboy provoked the 2011 Burkinabè protests, a series of popular protests, coupled with a military mutiny and a magistrates' strike, that called for the resignation of Compaoré, democratic reforms, higher wages for troops and public servants and economic freedom.[53][54][55] As a result, governors were replaced and wages for public servants were raised.[56][57] In April 2011, there was an army mutiny; the president named new chiefs of staff, and a curfew was imposed in Ouagadougou.[58]

Compaoré's government played the role of negotiator in several West-African disputes, including the 2010–11 Ivorian crisis, the Inter-Togolese Dialogue (2007), and the 2012 Malian Crisis.

Kafando presidency

Starting on 28 October 2014 protesters began to march and demonstrate in Ouagadougou against President Compaoré, who appeared ready to amend the constitution and extend his 27-year rule. On 30 October some protesters set fire to the parliament building[59] and took over the national TV headquarters.[60] Ouagadougou International Airport closed and MPs suspended the vote on changing the constitution (the change would have allowed Compaoré to stand for re-election in 2015). Later in the day, the military dissolved all government institutions and imposed a curfew.[61]

On 31 October 2014, President Compaoré, facing mounting pressure, resigned after 27 years in office.[62] Lt. Col. Isaac Zida said that he would lead the country during its transitional period before the planned 2015 presidential election, but there were concerns over his close ties to the former president.[63] In November 2014 opposition parties, civil-society groups and religious leaders adopted a plan for a transitional authority to guide Burkina Faso to elections.[64] Under the plan Michel Kafando became the transitional President of Burkina Faso and Lt. Col. Zida became the acting Prime Minister and Defense Minister.

On 16 September 2015, the Regiment of Presidential Security (RSP) carried out a coup d'état, seizing the president and prime minister and then declaring the National Council for Democracy the new national government.[65] However, on 22 September 2015, the coup leader, Gilbert Diendéré, apologized and promised to restore civilian government.[66] On 23 September 2015 the prime minister and interim president were restored to power.[67]

Kaboré presidency and Jihadist insurgency (2015-2023)

General elections took place on 29 November 2015. Roch Marc Christian Kaboré won the election in the first round with 53.5% of the vote, defeating businessman Zéphirin Diabré, who took 29.7%.[68] Kaboré was sworn in as president on 29 December 2015.[69] Kaboré was re-elected in the general election of 22 November 2020, but his party Mouvement du Peuple pour le Progrès (MPP), failed to reach absolute parliamentary majority. It secured 56 seats out of a total of 127. The Congress for Democracy and Progress (CDP), the party of former President Blaise Compaoré, was distant second with 20 seats.[70]

A Jihadist insurgency began in August 2015, part of the Islamist insurgency in the Sahel. Between August 2015 and October 2016, seven different posts were attacked across the country.[71][72] On 15 January 2016, terrorists attacked the capital city of Ouagadougou, killing 30 people. Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and Al-Mourabitoune, which until then had mostly operated in neighbouring Mali, claimed responsibility for the attack.[73][74]

In 2016, attacks increased after a new group Ansarul Islam, led by imam Ibrahim Malam Dicko, was founded.[75][76] Its attacks focused particularly on Soum province[75][77] and it killed dozens of people in the attack on Nassoumbou on 16 December.[78]

Between 27 March – 10 April 2017, the governments of Mali, France, and Burkina Faso launched a joint operation named "Operation Panga," composed of 1,300 soldiers from the three countries, in Fhero forest, near the Burkina Faso-Mali border, considered a sanctuary for Ansarul Islam.[79][80] The head of Ansarul Islam, Ibrahim Malam Dicko, was killed in June 2017 and Jafar Dicko became leader.[81]

On 2 March 2018, Jama'at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin attacked the French embassy in Ouagadougou as well as the general staff of the Burkinabè army. Eight soldiers and eight attackers were killed, and a further 61 soldiers and 24 civilians were injured.[82] The insurgency expanded to the east of the country[83][84][85] and, in early October, the Armed Forces of Burkina Faso launched a major military operation in the country's East, supported by French forces.[86][87][88] According to Human Rights Watch, between mid-2018 to February 2019, at least 42 people were murdered by jihadists and a minimum of 116 mostly Fulani civilians were killed by military forces without trial.[89] The attacks increased significantly in 2019. According to the ACLED, armed violence in Burkina Faso jumped by 174% in 2019, with nearly 1,300 civilians dead and 860,000 displaced.[90] Jihadist groups also began to specifically target Christians.[91][92][93][94]

On 8 July 2020, the United States raised concerns after a Human Rights Watch report revealed mass graves with at least 180 bodies, which were found in northern Burkina Faso where soldiers were fighting jihadists.[95] On 4 June 2021, the Associated Press reported that according to the government of Burkina Faso, gunmen killed at least 100 people in Solhan village in northern Burkina Faso near the Niger border. A local market and several homes were also burned down. A government spokesman blamed jihadists. Heni Nsaibia, senior researcher at the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project said it was the deadliest attack recorded in Burkina Faso since the beginning of the jihadist insurgency.[96]

From 4–5 June 2021, unknown militants massacred over 170 people in the villages of Solhan and Tadaryat. Jihadists killed 80 people in Gorgadji on 20 August.[97] On 14 November, the Jama'at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin attacked a gendarmerie in Inata, killing 53 soldiers, the heaviest loss of life by the Burkinabe military during the insurgency, and a major morale loss in the country.[98] In December Islamists killed 41 people in an ambush, including the popular vigilante leader Ladji Yoro. Yoro was a central figure in the Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP) a pro-government militia that had taken a leading role in the struggle against Islamists.[99]

In 2023, shortly after the murder of a Catholic priest at the hands of insurgents, the bishop of Dori, Laurent Dabiré, claimed in an interview with Catholic charity Aid to the Church in Need that around 50% of the country was in the hands of Islamists.[100]

2022 coups d'état

In a successful coup on 24 January 2022, mutinying soldiers arrested and deposed President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré following gunfire.[101] The Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration (MPSR) supported by the military declared itself to be in power,[102][103] led by Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba.[104] On 31 January, the military junta restored the constitution and appointed Damiba interim president. In the aftermath of the coup, ECOWAS and the African Union suspended Burkina Faso's membership.[105][106] On 10 February, the Constitutional Council declared Damiba president of Burkina Faso.[107] He was sworn in as president on 16 February.[108] On 1 March 2022, the junta approved a charter allowing a military-led transition of 3 years.[109] The charter provides for the transition process to be followed by the holding of elections.[110] President Kaboré, who had been detained since the military junta took power, was released on 6 April 2022.[111]

The insurgency continued following the coup, with about 60% of the country under government control.[112] The Siege of Djibo began in February 2022[113][114] and continues as of June 2023.[115][116] Between 100 and 165 people were killed in Seytenga Department, Séno Province on 12–13 June and around 16,000 people fled their homes.[117][118] In June, the Government announced the creation of "military zones", which civilians were required to vacate so that the country's Armed and Security Forces could fight insurgents without any "hindrances".[119][120]

On 30 September, Damiba was ousted in a military coup led by Capt. Ibrahim Traoré.[121][122] This came eight months after Damiba seized power. The rationale given by Traore for the coup d'état was the purported inability of Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba to deal with an Islamist insurgency.[123] Damiba resigned and left the country.[124] On 6 October 2022, Captain Ibrahim Traore was officially appointed as president of Burkina Faso.[125] Apollinaire Joachim Kyélem de Tambèla was appointed interim Prime Minister on 21 October 2022.[126]

On 13 April 2023, authorities in Burkina Faso declared a mobilisation in order to give the nation all means necessary to combat terrorism and create a "legal framework for all the actions to be taken" against the insurgents in recapturing 40 percent of the national territory from Islamist insurgents.[127] On 20 April, the Rapid Intervention Brigade committed the Karma massacre, rounding up and executing civilians en masse. Between 60 and 156 civilians were killed.[128][129][130][131]

Government

The constitution of 2 June 1991 established a semi-presidential government: its parliament could be dissolved by the President of the Republic, who was to be elected for a term of seven years. In 2000, the constitution was amended to reduce the presidential term to five years and set term limits to two, preventing successive re-election. The amendment took effect during the 2005 elections.

The parliament consisted of one chamber known as the National Assembly, which had 111 seats with members elected to serve five-year terms. There was also a constitutional chamber, composed of ten members, and an economic and social council whose roles were purely consultative. The 1991 constitution created a bicameral parliament, but the upper house (Chamber of Representatives) was abolished in 2002.

The Compaoré administration had worked to decentralize power by devolving some of its powers to regions and municipal authorities. But the widespread distrust of politicians and lack of political involvement by many residents complicated this process. Critics described this as a hybrid decentralisation.[132]

Political freedoms are severely restricted in Burkina Faso. Human rights organizations had criticised the Compaoré administration for numerous acts of state-sponsored violence against journalists and other politically active members of society.[133][134]

The prime minister is head of government and is appointed by the president with the approval of the National Assembly. He is responsible for recommending a cabinet for appointment by the president.[135]

Constitution

In 2015, Kaboré promised to revise the 1991 constitution. The revision was completed in 2018. One condition prevents any individual from serving as president for more than ten years either consecutively or intermittently and provides a method for impeaching a president. A referendum on the constitution for the Fifth Republic was scheduled for 24 March 2019.[136]

Certain rights are also enshrined in the revised wording: access to drinking water, access to decent housing and a recognition of the right to civil disobedience, for example. The referendum was required because the opposition parties in Parliament refused to sanction the proposed text.[137]

Following the January 2022 coup d'état, the military dissolved the parliament, government and constitution.[138] On 31 January, the military junta restored the constitution,[139] but it was suspended again following the September 2022 coup d'état.[140]

Foreign relations

Burkina Faso is a member of the G5 Sahel, Community of Sahel–Saharan States, La Francophonie, Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, and United Nations. It is currently suspended from ECOWAS and the African Union.

Military

The army consists of some 6,000 men in voluntary service, augmented by a part-time national People's Militia composed of civilians between 25 and 35 years of age who are trained in both military and civil duties. According to Jane's Sentinel Country Risk Assessment, Burkina Faso's Army is undermanned for its force structure and poorly equipped, but has wheeled light-armour vehicles, and may have developed useful combat expertise through interventions in Liberia and elsewhere in Africa.[141]

In terms of training and equipment, the regular Army is believed to be neglected in relation to the élite Regiment of Presidential Security (French: Régiment de la Sécurité Présidentielle – RSP). Reports have emerged in recent years of disputes over pay and conditions.[142] There is an air force with some 19 operational aircraft, but no navy, as the country is landlocked. Military expenses constitute approximately 1.2% of the nation's GDP.

Law enforcement

Burkina Faso employs numerous police and security forces, generally modeled after organizations used by French police. France continues to provide significant support and training to police forces. The Gendarmerie Nationale is organized along military lines, with most police services delivered at the brigade level. The Gendarmerie operates under the authority of the Minister of Defence, and its members are employed chiefly in the rural areas and along borders.[143]

There is a municipal police force controlled by the Ministry of Territorial Administration; a national police force controlled by the Ministry of Security; and an autonomous Regiment of Presidential Security (Régiment de la Sécurité Présidentielle, or RSP), a 'palace guard' devoted to the protection of the President of the Republic. Both the gendarmerie and the national police are subdivided into both administrative and judicial police functions; the former are detailed to protect public order and provide security, the latter are charged with criminal investigations.[143]

All foreigners and citizens are required to carry photo ID passports, or other forms of identification or risk a fine, and police spot identity checks are commonplace for persons traveling by auto, bush-taxi, or bus.[144][145]

Administrative divisions

The country is divided into 13 administrative regions. These regions encompass 45 provinces and 301 departments. Each region is administered by a governor.

Geography

Burkina Faso lies mostly between latitudes 9° and 15° N (a small area is north of 15°), and longitudes 6° W and 3° E.

It is made up of two major types of countryside. The larger part of the country is covered by a peneplain, which forms a gently undulating landscape with, in some areas, a few isolated hills, the last vestiges of a Precambrian massif. The southwest of the country, on the other hand, forms a sandstone massif, where the highest peak, Ténakourou, is found at an elevation of 749 meters (2,457 ft). The massif is bordered by sheer cliffs up to 150 m (492 ft) high. The average altitude of Burkina Faso is 400 m (1,312 ft) and the difference between the highest and lowest terrain is no greater than 600 m (1,969 ft). Burkina Faso is therefore a relatively flat country.

The country owes its former name of Upper Volta to three rivers which cross it: the Black Volta (or Mouhoun), the White Volta (Nakambé) and the Red Volta (Nazinon). The Black Volta is one of the country's only two rivers which flow year-round, the other being the Komoé, which flows to the southwest. The basin of the Niger River also drains 27% of the country's surface.

The Niger's tributaries – the Béli, Gorouol, Goudébo, and Dargol – are seasonal streams and flow for only four to six months a year. They still can flood and overflow, however. The country also contains numerous lakes – the principal ones are Tingrela, Bam, and Dem. The country contains large ponds, as well, such as Oursi, Béli, Yomboli, and Markoye. Water shortages are often a problem, especially in the north of the country.

Burkina Faso lies within two terrestrial ecoregions: Sahelian Acacia savanna and West Sudanian savanna.[146]

Climate

Burkina Faso has a primarily tropical climate with two very distinct seasons. In the rainy season, the country receives between 600 and 900 mm (23.6 and 35.4 in) of rainfall; in the dry season, the harmattan – a hot dry wind from the Sahara – blows. The rainy season lasts approximately four months, May/June to September, and is shorter in the north of the country. Three climatic zones can be defined: the Sahel, the Sudan-Sahel, and the Sudan-Guinea. The Sahel in the north typically receives less than 600 mm (23.6 in)[147] of rainfall per year and has high temperatures, 5–47 °C (41–117 °F).

A relatively dry tropical savanna, the Sahel extends beyond the borders of Burkina Faso, from the Horn of Africa to the Atlantic Ocean, and borders the Sahara to its north and the fertile region of the Sudan to the south. Situated between 11° 3′ and 13° 5′ north latitude, the Sudan-Sahel region is a transitional zone with regards to rainfall and temperature. Further to the south, the Sudan-Guinea zone receives more than 900 mm (35.4 in)[147] of rain each year and has cooler average temperatures.

.jpg.webp)

Geographic and environmental causes can also play a significant role in contributing to Burkina Faso's food insecurity.[148] As the country is situated in the Sahel region, Burkina Faso experiences some of the most radical climatic variation in the world, ranging from severe flooding to extreme drought.[149] The unpredictable climatic shock that Burkina Faso citizens often face results in strong difficulties in being able to rely on and accumulate wealth through agricultural means.[150]

Burkina Faso's climate also renders its crops vulnerable to insect attacks, including attacks from locusts and crickets, which destroy crops and further inhibit food production.[151] Not only is most of the population of Burkina Faso dependent on agriculture as a source of income, but they also rely on the agricultural sector for food that will directly feed the household.[152] Due to the vulnerability of agriculture, more and more families are having to look for other sources of non-farm income,[153] and often have to travel outside of their regional zone to find work.[152]

Natural resources

Burkina Faso's natural resources include gold, manganese, limestone, marble, phosphates, pumice, and salt.

Wildlife

Burkina Faso has a larger number of elephants than many countries in West Africa. Lions, leopards and buffalo can also be found here, including the dwarf or red buffalo, a smaller reddish-brown animal which looks like a fierce kind of short-legged cow. Other large predators live in Burkina Faso, such as the cheetah, the caracal or African lynx, the spotted hyena and the African wild dog, one of the continent's most endangered species.[154]

Burkina Faso's fauna and flora are protected in four national parks:

- The W National Park in the east which passes Burkina Faso, Benin, and Niger

- The Arly Wildlife Reserve (Arly National Park in the east)

- The Léraba-Comoé Classified Forest and Partial Reserve of Wildlife in the west

- The Mare aux Hippopotames in the west

and several reserves: see List of national parks in Africa and Nature reserves of Burkina Faso.

Economy

.svg.png.webp)

The value of Burkina Faso's exports fell from $2.77 billion in 2011 to $754 million in 2012.[155] Agriculture represents 32% of its gross domestic product and occupies 80% of the working population. It consists mostly of rearing livestock. Especially in the south and southwest, the people grow crops of sorghum, pearl millet, maize (corn), peanuts, rice and cotton, with surpluses to be sold. A large part of the economic activity of the country is funded by international aid, despite having gold ores in abundance.

The top five export commodities in 2017 were, in order of importance: gems and precious metals, US$1.9 billion (78.5% of total exports), cotton, $198.7 million (8.3%), ores, slag, ash, $137.6 million (5.8%), fruits, nuts: $76.6 million (3.2%) and oil seeds: $59.5 million (2.5%).[156]

A December 2018 report from the World Bank indicates that in 2017, economic growth increased to 6.4% in 2017 (vs. 5.9% in 2016) primarily due to gold production and increased investment in infrastructure. The increase in consumption linked to growth of the wage bill also supported economic growth. Inflation remained low, 0.4% that year but the public deficit grew to 7.7% of GDP (vs. 3.5% in 2016). The government was continuing to get financial aid and loans to finance the debt. To finance the public deficit, the Government combined concessional aid and borrowing on the regional market. The World Bank said that the economic outlook remained favorable in the short and medium term, although that could be negatively impacted. Risks included high oil prices (imports), lower prices of gold and cotton (exports) as well as terrorist threat and labour strikes.[157]

Burkina Faso is part of the West African Monetary and Economic Union (UMEOA) and has adopted the CFA franc. This is issued by the Central Bank of the West African States (BCEAO), situated in Dakar, Senegal. The BCEAO manages the monetary and reserve policy of the member states, and provides regulation and oversight of financial sector and banking activity. A legal framework regarding licensing, bank activities, organizational and capital requirements, inspections and sanctions (all applicable to all countries of the Union) is in place, having been reformed significantly in 1999. Microfinance institutions are governed by a separate law, which regulates microfinance activities in all WAEMU countries. The insurance sector is regulated through the Inter-African Conference on Insurance Markets (CIMA).[158]

In 2018, tourism was almost non-existent in large parts of the country. The U.S. government (and others) warn their citizens not to travel into large parts of Burkina Faso: "The northern Sahel border region shared with Mali and Niger due to crime and terrorism. The provinces of Kmoandjari, Tapoa, Kompienga, and Gourma in East Region due to crime and terrorism".[159]

The 2018 CIA World Factbook provides this updated summary. "Burkina Faso is a poor, landlocked country that depends on adequate rainfall. Irregular patterns of rainfall, poor soil, and the lack of adequate communications and other infrastructure contribute to the economy's vulnerability to external shocks. About 80% of the population is engaged in subsistence farming and cotton is the main cash crop. The country has few natural resources and a weak industrial base. Cotton and gold are Burkina Faso's key exports ...The country has seen an upswing in gold exploration, production, and exports.

While the end of the political crisis has allowed Burkina Faso's economy to resume positive growth, the country's fragile security situation could put these gains at risk. Political insecurity in neighboring Mali, unreliable energy supplies, and poor transportation links pose long-term challenges." The report also highlights the 2018–2020 International Monetary Fund program, including the government's plan to "reduce the budget deficit and preserve critical spending on social services and priority public investments".[20]

A 2018 report by the African Development Bank Group discussed a macroeconomic evolution: "higher investment and continued spending on social services and security that will add to the budget deficit". This group's prediction for 2018 indicated that the budget deficit would be reduced to 4.8% of GDP in 2018 and to 2.9% in 2019. Public debt associated with the National Economic and Social Development Plan was estimated at 36.9% of GDP in 2017.[160]

Burkina Faso is a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).[161] The country also belongs to the United Nations, International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and World Trade Organization.[162]

Mining

There is mining of copper, iron, manganese, gold, cassiterite (tin ore), and phosphates.[163] These operations provide employment and generate international aid. Gold production increased 32% in 2011 at six gold mine sites, making Burkina Faso the fourth-largest gold producer in Africa, after South Africa, Mali and Ghana.[164]

A 2018 report indicated that the country expected record 55 tonnes of gold in that year, a two-thirds increase over 2013. According to Oumarou Idani, there is a more important issue. "We have to diversify production. We mostly only produce gold, but we have huge potential in manganese, zinc, lead, copper, nickel and limestone".[165]

Food insecurity

According to the Global Hunger Index, a multidimensional tool used to measure and track a country's hunger levels,[166] Burkina Faso ranked 65 out of 78 countries in 2013.[167] It is estimated that there are currently over 1.5 million children who are at risk of food insecurity in Burkina Faso, with around 350,000 children who are in need of emergency medical assistance.[167] However, only about a third of these children will actually receive adequate medical attention.[168] Only 11.4 percent of children under the age of two receive the daily recommended number of meals.[167] Stunted growth as a result of food insecurity is a severe problem in Burkina Faso, affecting at least a third of the population from 2008 to 2012.[169] Additionally, stunted children, on average, tend to complete less school than children with normal growth development,[168] further contributing to the low levels of education of the Burkina Faso population.[170]

The European Commission expects that approximately 500,000 children under age 5 in Burkina Faso will suffer from acute malnutrition in 2015, including around 149,000 who will suffer from its most life-threatening form.[171] Rates of micronutrient deficiencies are also high.[172] According to the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS 2010), 49 percent of women and 88 percent of children under the age of five suffer from anemia.[172] Forty percent of infant deaths can be attributed to malnutrition, and in turn, these infant mortality rates have decreased Burkina Faso's total work force by 13.6 percent, demonstrating how food security affects more aspects of life beyond health.[167]

These high rates of food insecurity and the accompanying effects are even more prevalent in rural populations compared to urban ones, as access to health services in rural areas is much more limited and awareness and education of children's nutritional needs is lower.[173]

An October 2018 report by USAid stated that droughts and floods remained problematic, and that "violence and insecurity are disrupting markets, trade and livelihoods activities in some of Burkina Faso's northern and eastern areas". The report estimated that over 954,300 people needed food security support, and that, according to UNICEF, an "estimated 187,200 children under 5 years of age will experience severe acute malnutrition". Agencies providing assistance at the time included USAID's Office of Food for Peace (FFP) working with the UN World Food Programme, the NGO Oxfam Intermón and ACDI/VOCA.[174]

Approaches to improving food security

World Food Programme

The United Nations' World Food Programme has worked on programs that are geared towards increasing food security in Burkina Faso. The Protracted Relief and Recovery Operation 200509 (PRRO) was formed to respond to the high levels of malnutrition in Burkina Faso, following the food and nutrition crisis in 2012.[175] The efforts of this project are mostly geared towards the treatment and prevention of malnutrition and include take home rations for the caretakers of those children who are being treated for malnutrition.[175] Additionally, the activities of this operation contribute to families' abilities to withstand future food crises. Better nutrition among the two most vulnerable groups, young children and pregnant women, prepares them to be able to respond better in times when food security is compromised, such as in droughts.[175]

The Country Programme (CP) has two parts: food and nutritional assistance to people with HIV/AIDS, and a school feeding program for all primary schools in the Sahel region.[176] The HIV/AIDS nutrition program aims to better the nutritional recovery of those who are living with HIV/AIDS and to protect at-risk children and orphans from malnutrition and food security.[176] As part of the school feeding component, the Country Programme's goals are to increase enrollment and attendance in schools in the Sahel region, where enrollment rates are below the national average.[175] Furthermore, the program aims at improving gender parity rates in these schools, by providing girls with high attendance in the last two years of primary school with take-home rations of cereals as an incentive to households, encouraging them to send their girls to school.[175]

The WFP concluded the formation of a subsequently approved plan in August 2018 "to support the Government's vision of 'a democratic, unified and united nation, transforming the structure of its economy and achieving a strong and inclusive growth through patterns of sustainable consumption and production.' It will take important steps in WFP's new strategic direction for strengthened national and local capacities to enable the Government and communities to own, manage, and implement food and nutrition security programmes by 2030".[177]

World Bank

The World Bank was established in 1944, and comprises five institutions whose shared goals are to end extreme poverty by 2030 and to promote shared prosperity by fostering income growth of the lower forty percent of every country.[178] One of the main projects the World Bank is working on to reduce food insecurity in Burkina Faso is the Agricultural Productivity and Food Security Project.[179] According to the World Bank, the objective of this project is to "improve the capacity of poor producers to increase food production and to ensure improved availability of food products in rural markets."[179] The Agricultural Productivity and Food Security Project has three main parts. Its first component is to work towards the improvement of food production, including financing grants and providing 'voucher for work' programs for households who cannot pay their contribution in cash.[179] The project's next component involves improving the ability of food products, particularly in rural areas.[179] This includes supporting the marketing of food products, and aims to strengthen the capabilities of stakeholders to control the variability of food products and supplies at local and national levels.[179] Lastly, the third component of this project focuses on institutional development and capacity building. Its goal is to reinforce the capacities of service providers and institutions who are specifically involved in project implementation.[179] The project's activities aim to build capacities of service providers, strengthen the capacity of food producer organizations, strengthen agricultural input supply delivery methods, and manage and evaluate project activities.[179]

The December 2018 report by the World Bank indicated that the poverty rate fell slightly between 2009 and 2014, from 46% to a still high 40.1%. The report provided this updated summary of the country's development challenges: "Burkina Faso remains vulnerable to climatic shocks related to changes in rainfall patterns and to fluctuations in the prices of its export commodities on world markets. Its economic and social development will, to some extent, be contingent on political stability in the country and the subregion, its openness to international trade, and export diversification".[180]

Infrastructure and services

Water

While services remain underdeveloped, the National Office for Water and Sanitation (ONEA), a state-owned utility company run along commercial lines, is emerging as one of the best-performing utility companies in Africa.[181] High levels of autonomy and a skilled and dedicated management have driven ONEA's ability to improve production of and access to clean water.[181]

Since 2000, nearly 2 million more people have access to water in the four principal urban centres in the country; the company has kept the quality of infrastructure high (less than 18% of the water is lost through leaks – one of the lowest in sub-Saharan Africa), improved financial reporting, and increased its annual revenue by an average of 12% (well above inflation).[181] Challenges remain, including difficulties among some customers in paying for services, with the need to rely on international aid to expand its infrastructure.[181] The state-owned, commercially run venture has helped the nation reach its Millennium Development Goal (MDG) targets in water-related areas, and has grown as a viable company.[181]

However, access to drinking water has improved over the last 28 years. According to UNICEF, access to drinking water has increased from 39 to 76% in rural areas between 1990 and 2015. In this same time span, access to drinking water increased from 75 to 97% in urban areas.[182]

Electricity

A 33-megawatt solar power plant in Zagtouli, near Ouagadougou, came online in late November 2017. At the time of its construction, it was the largest solar power facility in West Africa.[183]

Other

The growth rate in Burkina Faso is high although it continues to be plagued by corruption and incursions from terrorist groups from Mali and Niger.[184]

Transport

Transport in Burkina Faso is limited by relatively underdeveloped infrastructure.

As of June 2014 the main international airport, Ouagadougou Airport, had regularly scheduled flights to many destinations in West Africa as well as Paris, Brussels and Istanbul. The other international airport, Bobo Dioulasso Airport, has flights to Ouagadougou and Abidjan.

Rail transport in Burkina Faso consists of a single line which runs from Kaya to Abidjan in Ivory Coast via Ouagadougou, Koudougou, Bobo Dioulasso and Banfora. Sitarail operates a passenger train three times a week along the route.[185]

There are 15,000 kilometres of roads in Burkina Faso, of which 2,500 kilometres are paved.[186]

Science and technology

In 2009, Burkina Faso spent 0.20% of GDP on research and development (R&D), one of the lowest ratios in West Africa. There were 48 researchers (in full-time equivalents) per million inhabitants in 2010, which is more than twice the average for sub-Saharan Africa (20 per million population in 2013) and higher than the ratio for Ghana and Nigeria (39). It is, however, much lower than the ratio for Senegal (361 per million inhabitants). In Burkina Faso in 2010, 46% of researchers were working in the health sector, 16% in engineering, 13% in natural sciences, 9% in agricultural sciences, 7% in the humanities and 4% in social sciences.[187] Burkina Faso was ranked 124th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[188][189]

In January 2011, the government created the Ministry of Scientific Research and Innovation. Up until then, management of science, technology and innovation had fallen under the Department of Secondary and Higher Education and Scientific Research. Within this ministry, the Directorate General for Research and Sector Statistics is responsible for planning. A separate body, the Directorate General of Scientific Research, Technology and Innovation, co-ordinates research. This is a departure from the pattern in many other West African countries where a single body fulfils both functions. The move signals the government's intention to make science and technology a development priority.[187]

In 2012, Burkina Faso adopted a National Policy for Scientific and Technical Research, the strategic objectives of which are to develop R&D and the application and commercialization of research results. The policy also makes provisions for strengthening the ministry's strategic and operational capacities. One of the key priorities is to improve food security and self-sufficiency by boosting capacity in agricultural and environmental sciences. The creation of a centre of excellence in 2014 at the International Institute of Water and Environmental Engineering in Ouagadougou within the World Bank project provides essential funding for capacity-building in these priority areas.[187]

A dual priority is to promote innovative, effective and accessible health systems. The government wishes to develop, in parallel, applied sciences and technology and social and human sciences. To complement the national research policy, the government has prepared a National Strategy to Popularize Technologies, Inventions and Innovations (2012) and a National Innovation Strategy (2014). Other policies also incorporate science and technology, such as that on Secondary and Higher Education and Scientific Research (2010), the National Policy on Food and Nutrition Security (2014) and the National Programme for the Rural Sector (2011).[187]

In 2013, Burkina Faso passed the Science, Technology and Innovation Act establishing three mechanisms for financing research and innovation, a clear indication of high-level commitment. These mechanisms are the National Fund for Education and Research, the National Fund for Research and Innovation for Development and the Forum of Scientific Research and Technological Innovation.[187]

Demographics

.jpg.webp)

| Population[190][191] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1950 | 4.3 | ||

| 2000 | 11.6 | ||

| 2021 | 22.1 | ||

Burkina Faso is an ethnically integrated, secular state where most people are concentrated in the south and centre, where their density sometimes exceeds 48 inhabitants per square kilometre (120/sq mi). Hundreds of thousands of Burkinabè migrate regularly to Ivory Coast and Ghana, mainly for seasonal agricultural work. These flows of workers are affected by external events; the September 2002 coup attempt in Ivory Coast and the ensuing fighting meant that hundreds of thousands of Burkinabè returned to Burkina Faso. The regional economy suffered when they were unable to work.[192]

In 2015, most of the population belonged to "one of two West African ethnic cultural groups: the Voltaic and the Mandé. Voltaic Mossi make up about 50% of the population and are descended from warriors who moved to the area from Ghana around 1100, establishing an empire that lasted over 800 years".[11]

The total fertility rate of Burkina Faso is 5.93 children born per woman (2014 estimates), the sixth highest in the world.[193]

In 2009 the U.S. Department of State's Trafficking in Persons Report reported that slavery in Burkina Faso continued to exist and that Burkinabè children were often the victims.[194] Slavery in the Sahel states in general, is an entrenched institution with a long history that dates back to the trans-Saharan slave trade.[195] In 2018, an estimated 82,000 people in the country were living under "modern slavery" according to the Global Slavery Index.[196]

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ouagadougou  Bobo-Dioulasso |

1 | Ouagadougou | Centre | 1,475,223 |  Koudougou  Banfora | ||||

| 2 | Bobo-Dioulasso | Hauts-Bassins | 489,967 | ||||||

| 3 | Koudougou | Centre-Ouest | 88,184 | ||||||

| 4 | Banfora | Cascades | 75,917 | ||||||

| 5 | Ouahigouya | Nord | 73,153 | ||||||

| 6 | Pouytenga | Centre-Est | 60,618 | ||||||

| 7 | Kaya | Centre-Nord | 54,365 | ||||||

| 8 | Tenkodogo | Centre-Est | 44,491 | ||||||

| 9 | Fada N'gourma | Est | 41,785 | ||||||

| 10 | Houndé | Hauts-Bassins | 39,458 | ||||||

Ethnic groups

Burkina Faso's 17.3 million people belong to two major West African ethnic cultural groups: the Voltaic and the Mandé (whose common language is Dioula). The Voltaic Mossi make up about one-half of the population. The Mossi claim descent from warriors who migrated to present-day Burkina Faso from northern Ghana around 1100 AD. They established an empire that lasted more than 800 years. Predominantly farmers, the Mossi kingdom is led by the Mogho Naba, whose court is in Ouagadougou.[192]

Languages

Burkina Faso is a multilingual country. The official language is French, which was introduced during the colonial period. French is the principal language of administrative, political and judicial institutions, public services, and the press. It is the only language for laws, administration and courts. Altogether, an estimated 69 languages are spoken in the country,[198] of which about 60 languages are indigenous. The Mooré language is the most spoken language in Burkina Faso, spoken by about half the population, mainly in the central region around the capital, Ouagadougou.

According to the 2006 census, the languages spoken natively in Burkina Faso were Mooré by 40.5% of the population, Fula by 29.3%, Gourmanché by 6.1%, Bambara by 4.9%, Bissa by 3.2%, Bwamu by 2.1%, Dagara by 2%, San by 1.9%, Lobiri with 1.8%, Lyélé with 1.7%, Bobo and Sénoufo with 1.4% each, Nuni by 1.2%, Dafing by 1.1%, Tamasheq by 1%, Kassem by 0.7%, Gouin by 0.4%, Dogon, Songhai, and Gourounsi by 0.3% each, Ko, Koussassé, Sembla, and Siamou by 0.1% each, other national languages by 5%, other African languages by 0.2%, French (the official language) by 1.3%, and other non-indigenous languages by 0.1%.[199]

In the west, Mandé languages are widely spoken, the most predominant being Dioula (also known as Jula or Dyula), others including Bobo, Samo, and Marka. Fula is widespread, particularly in the north. Gourmanché is spoken in the east, while Bissa is spoken in the south.

Health

In 2016, the average life expectancy was estimated at 60 for males and 61 for females. In 2018, the under-five mortality rate and the infant mortality rate was 76 per 1000 live births.[200] In 2014, the median age of its inhabitants was 17 and the estimated population growth rate was 3.05%.[193]

In 2011, health expenditures was 6.5% of GDP; the maternal mortality ratio was estimated at 300 deaths per 100000 live births and the physician density at 0.05 per 1000 population in 2010. In 2012, it was estimated that the adult HIV prevalence rate (ages 15–49) was 1.0%.[201] According to the 2011 UNAIDS Report, HIV prevalence is declining among pregnant women who attend antenatal clinics.[202] According to a 2005 World Health Organization report, an estimated 72.5% of Burkina Faso's girls and women have had female genital mutilation, administered according to traditional rituals.[203]

Central government spending on health was 3% in 2001.[204] As of 2009, studies estimated there were as few as 10 physicians per 100,000 people.[205] In addition, there were 41 nurses and 13 midwives per 100,000 people.[205] Demographic and Health Surveys has completed three surveys in Burkina Faso since 1993, and had another in 2009.[206]

A Dengue fever outbreak in 2016 killed 20 patients. Cases of the disease were reported from all 12 districts of Ouagadougou.[207]

Religion

The government of Burkina Faso's 2019 census reported that 63.8% of the population practice Islam, and that the majority of this group belong to the Sunni branch,[14][208] while a small minority adheres to Shia Islam.[209] A significant number of Sunni Muslims identify with the Tijaniyah Sufi order.

The 2019 census also found that 26.3% of the population are Christians (20.1% being Roman Catholics and 6.2% members of Protestant denominations) and 9.0% follow traditional indigenous beliefs such as the Dogon religion, 0.2% have other religions, and 0.7% have none.[14][208]

Animists are the largest religious group in the country's Sud-Ouest region, forming 48.1% of its total population.[14]

Education

Education in Burkina Faso is divided into primary, secondary and higher education.[210] High school costs approximately CFA 25,000 (US$50) per year, which is far above the means of most Burkinabè families. Boys receive preference in schooling; as such, girls' education and literacy rates are far lower than their male counterparts. An increase in girls' schooling has been observed because of the government's policy of making school cheaper for girls and granting them more scholarships.

To proceed from primary to middle school, middle to high school or high school to college, national exams must be passed. Institutions of higher education include the University of Ouagadougou, The Polytechnic University of Bobo-Dioulasso, and the University of Koudougou, which is also a teacher training institution. There are some small private colleges in the capital city of Ouagadougou but these are affordable to only a small portion of the population.

There is also the International School of Ouagadougou (ISO), an American-based private school located in Ouagadougou.

The 2008 UN Development Program Report ranked Burkina Faso as the country with the lowest level of literacy in the world, despite a concerted effort to double its literacy rate from 12.8% in 1990 to 25.3% in 2008.[211]

Culture

Literature in Burkina Faso is based on the oral tradition, which remains important. In 1934, during French occupation, Dim-Dolobsom Ouedraogo published his Maximes, pensées et devinettes mossi (Maxims, Thoughts and Riddles of the Mossi), a record of the oral history of the Mossi people.[212]

The oral tradition continued to have an influence on Burkinabè writers in the post-independence Burkina Faso of the 1960s, such as Nazi Boni and Roger Nikiema.[213] The 1960s saw a growth in the number of playwrights being published.[212] Since the 1970s, literature has developed in Burkina Faso with many more writers being published.[214]

The theatre of Burkina Faso combines traditional Burkinabè performance with the colonial influences and post-colonial efforts to educate rural people to produce a distinctive national theatre. Traditional ritual ceremonies of the many ethnic groups in Burkina Faso have long involved dancing with masks. Western-style theatre became common during colonial times, heavily influenced by French theatre. With independence came a new style of theatre inspired by forum theatre aimed at educating and entertaining Burkina Faso's rural people.

Slam poetry is increasing in popularity in the country, in part due to the efforts of slam poet Malika Outtara.[215] She uses her skills to raise awareness around issues such as blood donation, albinism and the impact of COVID-19.[216][217]

Arts and crafts

In addition to several rich traditional artistic heritages among the peoples, there is a large artist community in Burkina Faso, especially in Ouagadougou. Much of the crafts produced are for the country's growing tourist industry.

Burkina Faso also hosts the International Art and Craft Fair, Ouagadougou. It is better known by its French name as SIAO, Le Salon International de l' Artisanat de Ouagadougou, and is one of the most important African handicraft fairs.

Cuisine

Typical of West African cuisine, Burkina Faso's cuisine is based on staple foods of sorghum, millet, rice, maize, peanuts, potatoes, beans, yams and okra.[218] The most common sources of animal protein are chicken, chicken eggs and freshwater fish. A typical Burkinabè beverage is Banji or Palm Wine, which is fermented palm sap; and Zoom-kom, or "grain water" purportedly the national drink of Burkina Faso. Zoom-kom is milky-looking and whitish, having a water and cereal base, best drunk with ice cubes. In the more rural regions, in the outskirts of Burkina, you would find Dolo, which is drink made from fermented millet.[219] In times of crisis, one legume native to Burkina, Zamnè, can be served as a main dish or in a sauce.[220]

Cinema

The cinema of Burkina Faso is an important part of the West African film industry and African film as a whole.[221] Burkina's contribution to African cinema started with the establishment of the film festival FESPACO (Festival Panafricain du Cinéma et de la Télévision de Ouagadougou), which was launched as a film week in 1969. Many of the nation's filmmakers are known internationally and have won international prizes.

For many years the headquarters of the Federation of Panafrican Filmmakers (FEPACI) was in Ouagadougou, rescued in 1983 from a period of moribund inactivity by the enthusiastic support and funding of President Sankara. (In 2006 the Secretariat of FEPACI moved to South Africa, but the headquarters of the organization is still in Ouagadougou.) Among the best known directors from Burkina Faso are Gaston Kaboré, Idrissa Ouedraogo and Dani Kouyate.[222] Burkina produces popular television series such as Les Bobodiouf. Internationally known filmmakers such as Ouedraogo, Kabore, Yameogo, and Kouyate make popular television series.

Sports

Sport in Burkina Faso is widespread and includes football, basketball, cycling, rugby union, handball, tennis, boxing and martial arts. Football is the most popular sport in Burkina Faso, played both professionally, and informally in towns and villages across the country. The national team is nicknamed "Les Etalons" ("the Stallions") in reference to the legendary horse of Princess Yennenga.

In 1998, Burkina Faso hosted the Africa Cup of Nations for which the Omnisport Stadium in Bobo-Dioulasso was built. Burkina Faso qualified for the 2013 African Cup of Nations in South Africa and reached the final, but then lost to Nigeria 0–1. The country has never qualified for a FIFA World Cup.[223]

Basketball is another sport which enjoys much popularity for both men and women.[224] The country's men's national team had its most successful year in 2013 when it qualified for the AfroBasket, the continent's prime basketball event.

At the 2020 Summer Olympics, the athlete Hugues Fabrice Zango won Burkina Faso's first Olympic medal, winning bronze in the men's triple jump.[225] Cricket is also picking up in Burkina Faso with Cricket Burkina Faso running a 10 club league.[226]

Music

The music of Burkina Faso includes the folk music of 60 different ethnic groups. The Mossi people, centrally located around the capital, Ouagadougou, account for 40% of the population while, to the south, Gurunsi, Gurma, Dagaaba and Lobi populations, speaking Gur languages closely related to the Mossi language, extend into the coastal states. In the north and east the Fulani of the Sahel preponderate, while in the south and west the Mande languages are common; Samo, Bissa, Bobo, Senufo and Marka. Burkinabé traditional music has continued to thrive and musical output remains quite diverse. Popular music is mostly in French: Burkina Faso has yet to produce a major pan-African success.

Media

The nation's principal media outlet is its state-sponsored combined television and radio service, Radiodiffusion-Télévision Burkina (RTB).[227] RTB broadcasts on two medium-wave (AM) and several FM frequencies. Besides RTB, there are privately owned sports, cultural, music, and religious FM radio stations. RTB maintains a worldwide short-wave news broadcast (Radio Nationale Burkina) in the French language from the capital at Ouagadougou using a 100 kW transmitter on 4.815 and 5.030 MHz.[228]

Attempts to develop an independent press and media in Burkina Faso have been intermittent. In 1998, investigative journalist Norbert Zongo, his brother Ernest, his driver, and another man were assassinated by unknown assailants, and the bodies burned. The crime was never solved.[229] However, an independent Commission of Inquiry later concluded that Norbert Zongo was killed for political reasons because of his investigative work into the death of David Ouedraogo, a chauffeur who worked for François Compaoré, President Blaise Compaoré's brother.[230][231]

In January 1999, François Compaoré was charged with the murder of David Ouedraogo, who had died as a result of torture in January 1998. The charges were later dropped by a military tribunal after an appeal. In August 2000, five members of the President's personal security guard detail (Régiment de la Sécurité Présidentielle, or RSP) were charged with the murder of Ouedraogo. RSP members Marcel Kafando, Edmond Koama, and Ousseini Yaro, investigated as suspects in the Norbert Zongo assassination, were convicted in the Ouedraogo case and sentenced to lengthy prison terms.[230][231]

Since the death of Norbert Zongo, several protests regarding the Zongo investigation and treatment of journalists have been prevented or dispersed by government police and security forces. In April 2007, popular radio reggae host Karim Sama, whose programs feature reggae songs interspersed with critical commentary on alleged government injustice and corruption, received several death threats.[232]

Sama's personal car was later burned outside the private radio station Ouaga FM by unknown vandals.[233] In response, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) wrote to President Compaoré to request his government investigate the sending of e-mailed death threats to journalists and radio commentators in Burkina Faso who were critical of the government.[229] In December 2008, police in Ouagadougou questioned leaders of a protest march that called for a renewed investigation into the unsolved Zongo assassination. Among the marchers was Jean-Claude Meda, the president of the Association of Journalists of Burkina Faso.[234]

Cultural festivals and events

Every two years, Ouagadougou hosts the Panafrican Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO), the largest African cinema festival on the continent (February, odd years).

Held every two years since 1988, the International Art and Craft Fair, Ouagadougou (SIAO), is one of Africa's most important trade shows for art and handicrafts (late October-early November, even years).

Also every two years, the Symposium de sculpture sur granit de Laongo takes place on a site located about 35 kilometres (22 miles) from Ouagadougou, in the province of Oubritenga.

The National Culture Week of Burkina Faso, better known by its French name La Semaine Nationale de la culture (SNC), is one of the most important cultural activities of Burkina Faso. It is a biennial event which takes place every two years in Bobo Dioulasso, the second-largest city in the country.

The Festival International des Masques et des Arts (FESTIMA), celebrating traditional masks, is held every two years in Dédougou.

See also

References

- ↑ "Burkina Faso". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 December 2019. (Archived 2019 edition)

- ↑ Ndiaga, Thiam; Mimault, Anne (30 September 2022). "Burkina Faso soldiers announce overthrow of military government". Ouagadougou. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

Traore appeared on television surrounded by soldiers and announced the government was dissolved, the constitution suspended and the borders closed.

- ↑ "Appolinaire Jean Kyelem de Tembela : "j'ai toujours voulu faire un livre sur la révolution"". thomassankara.net (in French). 4 April 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ↑ Sylvestre-Treiner, Anna; Wendpouiré Nana, Michel (25 October 2022). "Burkina Faso: Apollinaire Kyélem de Tambèla, Captain Traoré's surprise prime minister". The Africa Report. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Burkina Faso". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (BF)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ↑ "Distribution of family income – Gini index". The World Factbook. CIA. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- ↑ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ↑ CFA Franc BCEAO. Codes: XOF / 952 ISO 4217 currency names and code elements Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine. ISO.

- ↑ "burkina-faso noun – Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes | Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com". www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- 1 2 "Burkina Faso Population 2021 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)". worldpopulationreview.com.

- ↑ "Burkina Faso country profile". BBC News. 13 April 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ↑ "Burkina Faso restores constitution, names coup leader president". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Aib, Az (1 July 2022). "Burkina: 48,1% de la population du Sud-ouest pratique l'Animisme (officiel)". AIB - Agence d'Information du Burkina (in French). Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ↑ "Burkina abandons French as an official language". 7 December 2023.

- ↑ Brion, Corinne (November 2014). "Global voices Burkina Faso: Two languages are better than one". Phi Delta Kappan. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ↑ "Burkina Faso § People and Society". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 11 March 2020. (Archived 2020 edition)

- ↑ Roy, Christopher D. "Countries of Africa: Burkina Faso," Art and Life in Africa, "Countries Resources". Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.