Calhoun County | |

|---|---|

Calhoun County Courthouse in Hardin | |

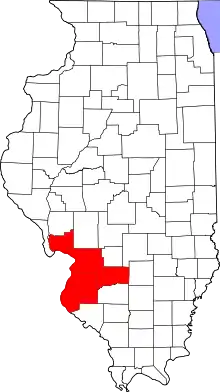

Location within the U.S. state of Illinois | |

Illinois's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 39°10′N 90°40′W / 39.16°N 90.67°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1825 |

| Named for | John C. Calhoun |

| Seat | Hardin |

| Largest village | Hardin |

| Area | |

| • Total | 284 sq mi (740 km2) |

| • Land | 254 sq mi (660 km2) |

| • Water | 30 sq mi (80 km2) 10.5% |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 4,437 |

| • Density | 16/sq mi (6.0/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 15th |

Calhoun County is a county in the U.S. state of Illinois. As of the 2020 census, the population was 4,437,[1] making it Illinois’ third-least populous county. Its county seat and biggest community is Hardin, with a population of 801.[2] Its smallest incorporated community is Hamburg, with a population of 99. Calhoun County is at the tip of the peninsula formed by the courses of the Mississippi and Illinois rivers above their confluence and is almost completely surrounded by water. Calhoun County is sparsely populated; it has just five municipalities, all of them villages.[3]

Calhoun County is part of the Metro-East portion of the St. Louis, MO-IL Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

Calhoun County was settled by Americans during the very early 19th century, and officially organized in 1825. It was named for Vice President John C. Calhoun, in addition to the Calhoun family that was prominent in the area at the time. The southern side of the county, covered in thick forest, was untouched until the population began to expand in the late 1840s with the arrival of German immigrants. Land was cleared for farming, exporting lumber, and constructing spacious log barns, typically 200 square feet (19 m2) in size, which were a "trademark of successful German farmers."[4]

The territory was originally settled by indigenous people who occupied the resource-rich river valleys near waterways. The remains of their occupation have provided some of the most valuable archaeological information in the country. The county's archaeological record chronicles more than 10,000 years of continuous human occupation by Native Americans.

In 1680, French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle recorded in his diary historic Native American raids by the Iroquois against the Illinois tribes along the Illinois River. La Salle recounts the aftermath of a massacre of the Illinois by the Iroquois in South Calhoun County writing, "As the French drew near to the mouth of the Illinois, they saw a meadow to the right, and, on the farthest verge, several human figures erect, yet motionless. They landed and cautiously examined the place. The long grass was trampled down and all around were strewn the relics of the hideous orgies which formed the ordinary sequel of an Iroquois victory. The figures they had seen were the half consumed bodies of women still bound to the stakes where they had been tortured. Other sights there were, too revolting for record. All the remains were of women and children; the men, it seems, had fled, and left them to their fate. The French descended the river and soon came to the mouth."[5] The massacre is noted as taking place in the last week of November, 1680, about a mile above the site of the Deer Plain Ferry which is no longer in operation, at a place now known as Marshall's Landing. Many skulls, parts of skeletons, and weapons have still been found near this spot by farmers during plowing.[5]

The first European settler to make his home in what is now Calhoun County was a man only known today by his last name, O'Neal. He came in the year 1801 and settled in the south part of the county at Point Precinct at what has been called "Two Branches". Although his name might have one assume differently, O'Neal was a French trapper and had made his way there from Acadia. O'Neal lived in Point Precinct a number of years before any other European settlers came to that region, and when they did come he refused to mingle with them. He lived in a small cave which he had dug, and which was located about a quarter of a mile from the Mississippi River. He continued to live in this cave until his death in 1842, and after that he was referred to as "The Hermit" due to the fact that he would not visit the other settlers or allow them to come to his place. In 1850, Soloman Lammy, who then owned the farm upon which the cave was located.

The next settlers to come to the area were French trappers and people of mixed ancestry, who started a community about a mile above what was called the Deep Plain Ferry, on the Illinois River, in the southern part of the county. They remained until about 1815 when they were driven out by the very high water. Another French settlement was located at Cap au Gris (which means Cape of Grit or Grindstone). This place was located at the site of what was once the West Point Ferry, in Richwoods Precinct. The French settlers who lived here came sometime after 1800 and by the year 1811 there were 20 families, who had a small village on the bank of the river, and cultivated a common field of about 500 acres. The field was located on the level land about a mile from the site of their town. One writer said that these families were driven away by the Native Americans in 1814, but there is some doubt as to the accuracy of the statement as John Shaw who took part in battles with the natives in the region and was a community leader at the time does not mention in his writings any harm coming to the settlers at Cap au Gris.

As early pioneers continued to settle in Calhoun County there is evidence of troubled relations between the European settlers and the Native Americans. There are two known cases on kidnapping of settler's children. One being the three-year-old son of Jacob Pruden. Mr. Pruden settled in the county in 1829 near what was called the old Seuier place, about five miles below the present site of Hardin. The boy was recaptured from the Native Americans five days after he had been taken, and had not been harmed. The second case was the kidnapping of Joe DeGerlia, the son of Antoine DeGerlia Sr., the first settler in the French Hollow area. Mr. DeGerlia had not yet finished building his home, when his small son, Joe, was taken, however the family oral history may suggest Joe was bartered or sold. Nearly thirty years later a man who was acquainted with the history of the DeGerlia family was traveling among the tribes of the Indian Territory, and there he heard the story of a boy that had been kidnapped many years before from a place not far from where the Illinois River flows into the Mississippi. He investigated the story and found that the boy was Joe DeGerlia of a family in Calhoun. Joe had been taught the Native's language and had grown to manhood among the remnants of the tribe that had taken him southwest. Joe returned to Calhoun, married, and lived in the French Hollow area. The descendants of the DeGerlia family are still living on the same land Antoine DeGerlia settled over 200 years ago.[5]

The most well-known historical event to impact Calhoun County is likely the Great Flood of 1993. Calhoun County is a peninsula nestled between the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers, which both saw record flooding during 1993. The Great Flood of 1993, the name it is now known as, impacted several villages in Calhoun and completely destroyed the village of East Hardin which once sat across the Joe Page Bridge when the Nutwood levee broke in August 1993. The flood also closed all crossings over the rivers in the county including the bridge in Hardin and all ferries, leaving residents without access to groceries, gasoline, or other supplies. All supplies needed had to be flown in via helicopter or retrieved on a 2 hour long drive north via the only road existing Calhoun without a water passage or was not covered by flood water. The Great Flood of 1993 was devastating to Calhoun County because it destroyed homes, infrastructure, and caused many residents to leave. The population of the county has yet to recover.

Marquette and Joliet Exploration

In the town of Grafton, IL, downriver from Calhoun County, a statue was placed to mark where Marquette and Joliet are claimed to have landed during their famous exploration. Historians base claims upon one of Marquette's diary entries. In the entry Marquette mentions that they entered the mouth of the Illinois River early in the morning, which would mean that the party had camped somewhere below the mouth during the previous evening. The territory about Grafton is high and a desirable place to camp, while the land opposite, on the Missouri side is low and swampy and would have made an undesirable camping place. However, local historians in Calhoun County claim that the true stopping point of the expedition is a place now called "Perrin's Ledge", located several miles above Kampsville, IL. Their claims seem to be much better supported by Marquette's diary where he writes, "We entered the mouth of the Illinois River very early in the morning", and further on he says: "We spent the night with some friendly Indians." From other parts of the diary we find that the party was traveling about twenty -five miles a day up the Mississippi River, but it is likely that they made better time on the Illinois River because there would be less current. If they were traveling at a rate of slightly better than twenty-five miles a day and entered the river early in the morning (this was the last week in August) they would have been in the Kampsville area by evening. At the place now called "Perrin's Ledge" several large Indian mounds are to be found and the first settlers in this part of the county found evidences to show that a small Indian village had been located here. Here at the ledge, the bluff is very near to the water and the rocks project themselves in such a manner that they can be seen for miles down the river. From a distance they have the appearance of the walls of a castle. There can be little doubt that it was at this place that the Marquette-Joliet party stopped for the night.[5]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 284 square miles (740 km2), of which 254 square miles (660 km2) is land and 30 square miles (78 km2) (10.5%) is water.[6]

Calhoun County is a narrow 37-mile (60 km)-long peninsula of mostly high, rolling ground located between the Mississippi River and the Illinois River. The rolling hills escaped the leveling of glaciers.

County transportation is served by two state-operated, free ferries crossing the Illinois River (the Brussels Ferry in the south and the Kampsville ferry in the north). The Golden Eagle ferry, which is privately operated and charges a toll, crosses the Mississippi River to St. Charles County, Missouri. A bridge spans the Illinois River at Hardin. Land routes connect to the north to bordering Pike County.

When transportation was mainly by river, the county had many prosperous farms and orchards. It still produces a major portion of the peach crop of Illinois, and farmers raise corn and other commodities. The hotel in Brussels dates from 1847, when it was a stagecoach stop.

Tourists visit the area for the natural environment of the Illinois River valley and for its proximity to the Great River Road on the Illinois side. It includes part of the Two Rivers National Wildlife Refuge and attracts thousands of birds in migration seasons as part of the Mississippi Flyway. The county has several designated historic districts in the villages and properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Calhoun County was added to the St. Louis Metropolitan Statistical Area in 2003, along with Bond and Macoupin counties in Illinois, and Washington County, Missouri.

The Center for American Archeology is located in Kampsville in the northern part of the county. It has been the center for study of prehistoric indigenous culture in the area. It has created educational opportunities for children and adults to participate in its archaeological digs.

Adjacent counties

- Greene County – northeast

- Jersey County – east

- St. Charles County, Missouri – south

- Lincoln County, Missouri – west

- Pike County, Illinois – north

- Pike County, Missouri – northwest

National protected area

Major highways

Climate and weather

| Hardin, Illinois | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In recent years, average temperatures in the county seat of Hardin have ranged from a low of 19 °F (−7 °C) in January to a high of 90 °F (32 °C) in July, although a record low of −24 °F (−31 °C) was recorded in January 1979 and a record high of 116 °F (47 °C) was recorded in July 1954. Average monthly precipitation ranged from 2.01 inches (51 mm) in January to 4.10 inches (104 mm) in May.[7]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1830 | 1,090 | — | |

| 1840 | 1,740 | 59.6% | |

| 1850 | 3,231 | 85.7% | |

| 1860 | 5,144 | 59.2% | |

| 1870 | 6,562 | 27.6% | |

| 1880 | 7,467 | 13.8% | |

| 1890 | 7,652 | 2.5% | |

| 1900 | 8,917 | 16.5% | |

| 1910 | 8,610 | −3.4% | |

| 1920 | 8,245 | −4.2% | |

| 1930 | 8,034 | −2.6% | |

| 1940 | 8,207 | 2.2% | |

| 1950 | 6,898 | −15.9% | |

| 1960 | 5,933 | −14.0% | |

| 1970 | 5,675 | −4.3% | |

| 1980 | 5,867 | 3.4% | |

| 1990 | 5,322 | −9.3% | |

| 2000 | 5,084 | −4.5% | |

| 2010 | 5,089 | 0.1% | |

| 2020 | 4,437 | −12.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[8] 1790-1960[9] 1900-1990[10] 1990-2000[11] 2010[12] | |||

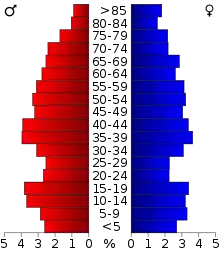

As of the 2010 census, there were 5,089 people, 2,085 households, and 1,447 families residing in the county.[13] The population density was 20.0 inhabitants per square mile (7.7/km2). There were 2,835 housing units at an average density of 11.2 per square mile (4.3/km2).[6] The racial makeup of the county was 98.9% white, 0.2% Asian, 0.2% American Indian, 0.1% black or African American, 0.2% from other races, and 0.4% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 0.8% of the population.[13] In terms of ancestry, 46.2% were German, 14.7% were American, 12.4% were Irish, and 9.5% were English.[14]

Of the 2,085 households, 28.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 59.2% were married couples living together, 7.0% had a female householder with no husband present, 30.6% were non-families, and 27.3% of all households were made up of individuals. The average household size was 2.40 and the average family size was 2.90. The median age was 44.6 years.[13]

The median income for a household in the county was $44,891 and the median income for a family was $57,627. Males had a median income of $42,917 versus $34,514 for females. The per capita income for the county was $23,109. About 7.2% of families and 11.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 12.3% of those under age 18 and 13.2% of those age 65 or over.[15]

Communities

Villages

Unincorporated communities

Population ranking

The population ranking of the following table is based on the 2020 census of Calhoun County.

† county seat

| Rank | Place | Municipal type | Population (2020 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | † Hardin | Village | 801 |

| 2 | Kampsville | Village | 310 |

| 3 | Batchtown | Village | 170 |

| 4 | Brussels | Village | 116 |

| 5 | Hamburg | Village | 99 |

Politics

For two generations following the Civil War, Calhoun County was typical of the German counties on the Illinois side of the Mississippi River in being heavily Democratic as it had opposed the “Yankee” American Civil War. However, many citizens of Calhoun County enlisted in military on the side of Union during the war. The people of Calhoun generally were not sympathetic to the Confederate cause, as there are accounts of Calhoun citizens harassing Confederate sympathizers and Calhoun was often the target of Confederate desperados who would steal horses, burn barns, and generally terrorize the locals. Only when German-Americans were offended at Woodrow Wilson's policies towards Germany did the county vote Republican for the first time in 1920, and it narrowly repeated that in the GOP landslides of 1924 and 1928. The county did turn strongly Republican due again to opposition to war involvement in 1940, and remained Republican-leaning for three decades. Between 1970 and 2008 Calhoun turned Democratic once more – George Bush senior in 1992 won a smaller proportion of the vote than Alf Landon in 1936 or William Howard Taft in 1912. The county leaned heavily Republican during the 2010s, so that Joe Biden’s 2020 vote percentage is the worst ever by a Democrat. Interestingly, despite Donald Trump defeating Hillary Clinton by almost 40 points in 2016, Calhoun County concurrently voted Democratic in the Senate race, narrowly supporting Tammy Duckworth over Mark Kirk.[16]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 2,046 | 73.78% | 677 | 24.41% | 50 | 1.80% |

| 2016 | 1,721 | 66.94% | 739 | 28.74% | 111 | 4.32% |

| 2012 | 1,440 | 55.90% | 1,080 | 41.93% | 56 | 2.17% |

| 2008 | 1,221 | 45.12% | 1,423 | 52.59% | 62 | 2.29% |

| 2004 | 1,317 | 48.67% | 1,367 | 50.52% | 22 | 0.81% |

| 2000 | 1,229 | 47.23% | 1,310 | 50.35% | 63 | 2.42% |

| 1996 | 941 | 31.23% | 1,676 | 55.63% | 396 | 13.14% |

| 1992 | 745 | 26.58% | 1,519 | 54.19% | 539 | 19.23% |

| 1988 | 1,238 | 44.37% | 1,544 | 55.34% | 8 | 0.29% |

| 1984 | 1,648 | 53.04% | 1,443 | 46.44% | 16 | 0.51% |

| 1980 | 1,591 | 54.96% | 1,208 | 41.73% | 96 | 3.32% |

| 1976 | 1,364 | 46.35% | 1,549 | 52.63% | 30 | 1.02% |

| 1972 | 1,705 | 56.51% | 1,299 | 43.06% | 13 | 0.43% |

| 1968 | 1,542 | 49.12% | 1,329 | 42.34% | 268 | 8.54% |

| 1964 | 1,288 | 41.64% | 1,805 | 58.36% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 1,654 | 50.63% | 1,608 | 49.22% | 5 | 0.15% |

| 1956 | 1,892 | 55.79% | 1,498 | 44.18% | 1 | 0.03% |

| 1952 | 1,915 | 56.81% | 1,454 | 43.13% | 2 | 0.06% |

| 1948 | 1,526 | 52.21% | 1,377 | 47.11% | 20 | 0.68% |

| 1944 | 1,956 | 60.35% | 1,271 | 39.22% | 14 | 0.43% |

| 1940 | 2,516 | 60.51% | 1,625 | 39.08% | 17 | 0.41% |

| 1936 | 1,883 | 45.90% | 2,058 | 50.17% | 161 | 3.92% |

| 1932 | 1,239 | 35.36% | 2,229 | 63.61% | 36 | 1.03% |

| 1928 | 1,594 | 50.16% | 1,551 | 48.80% | 33 | 1.04% |

| 1924 | 1,136 | 48.12% | 1,115 | 47.23% | 110 | 4.66% |

| 1920 | 1,367 | 64.82% | 703 | 33.33% | 39 | 1.85% |

| 1916 | 1,168 | 48.40% | 1,181 | 48.94% | 64 | 2.65% |

| 1912 | 373 | 30.62% | 602 | 49.43% | 243 | 19.95% |

| 1908 | 735 | 42.58% | 905 | 52.43% | 86 | 4.98% |

| 1904 | 730 | 42.77% | 815 | 47.74% | 162 | 9.49% |

| 1900 | 873 | 41.99% | 1,175 | 56.52% | 31 | 1.49% |

| 1896 | 795 | 40.03% | 1,176 | 59.21% | 15 | 0.76% |

| 1892 | 563 | 35.68% | 840 | 53.23% | 175 | 11.09% |

Education

- Brussels Community Unit School District 42

- Calhoun Community Unit School District 40

See also

References

- Specific

- ↑ "Calhoun County, Illinois". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Visitors Guide to Calhoun County". greatriverroad.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- ↑ Price, H. Wayne (Summer 1980). "The Double-Crib Log Barns of Calhoun County". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 73 (2): 140–160.

- 1 2 3 4 "History of Calhoun County and its people up to the year 1910". 1933.

- 1 2 "Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- 1 2 "Monthly Averages for Hardin, Illinois". The Weather Channel. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ↑ "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ↑ "DP02 SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ↑ "DP03 SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ↑ "Illinois Election Results 2016: Senate Live Map by County, Real-Time Voting Updates". Politico.

- ↑ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- General