|

|---|

Canadian federalism (French: fédéralisme canadien) involves the current nature and historical development of the federal system in Canada.

Canada is a federation with eleven components: the national Government of Canada and ten provincial governments. All eleven governments derive their authority from the Constitution of Canada. There are also three territorial governments in the far north, which exercise powers delegated by the federal parliament, and municipal governments which exercise powers delegated by the province or territory. Each jurisdiction is generally independent from the others in its realm of legislative authority.[1] The division of powers between the federal government and the provincial governments is based on the principle of exhaustive distribution: all legal issues are assigned to either the federal Parliament or the provincial Legislatures.

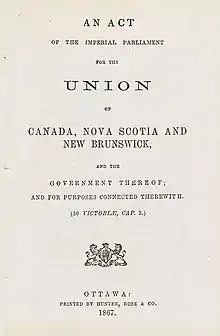

The division of powers is set out in the Constitution Act, 1867 (originally called the British North America Act, 1867), a key document in the Constitution of Canada. Some amendments to the division of powers have been made in the past century and a half, but the 1867 act still sets out the basic framework of the federal and provincial legislative jurisdictions. The divvying of power is reliant upon the "division" of the unitary Canadian Crown and, with it, of Canadian sovereignty, among the country's 11 jurisdictions.

The federal nature of the Canadian constitution was a response to the colonial-era diversity of the Maritimes and the Province of Canada, particularly the sharp distinction between the French-speaking inhabitants of Lower Canada and the English-speaking inhabitants of Upper Canada and the Maritimes. John A. Macdonald,[2] Canada's first prime minister, originally favoured a unitary system.[3]

History

Origins

The foundations of Canadian federalism were laid at the Quebec Conference of 1864. The Quebec Resolutions were a compromise between those who wanted sovereignty vested in the federal government and those who wanted it vested in the provinces. The compromise based the federation on the constitution of the British Empire, under which the legal sovereignty of imperial power was modified by the conventions of colonial responsible government, making colonies of settlement (such as those of British North America) self-governing in domestic affairs. A lengthy political process ensued before the Quebec Resolutions became the British North America Act of 1867. This process was dominated by John A. Macdonald, who joined British officials in attempting to make the federation more centralized than that envisaged by the Resolutions.[4]

The resulting constitution was couched in more centralist terms than intended. As prime minister, Macdonald tried to exploit this discrepancy to impose his centralist ideal against chief opponent Oliver Mowat. In a series of political battles and court cases from 1872 to 1896,[lower-alpha 1] Mowat reversed Macdonald's early victories and entrenched the co-ordinated sovereignty which he saw in the Quebec Resolutions.[6] In 1888, Edward Blake summarized that view: "[It is] a federal as distinguished from a legislative union, but a union composed of several existing and continuing entities ... [The provinces are] not fractions of a unit but units of a multiple. The Dominion is the multiple and each province is a unit of that multiple ..."[7] The accession of Wilfrid Laurier as prime minister inaugurated a new phase of constitutional consensus, marked by a more-egalitarian relationship between the jurisdictions. The federal government's quasi-imperial powers of disallowance and reservation, which Macdonald abused in his efforts to impose a centralised government, fell into disuse.

1914–1960

During World War I, the federal Crown's power was extended with the introduction of income taxes and passage of the War Measures Act, the scope of which was determined by several court cases.[lower-alpha 2] The constitution's restrictions of parliamentary power were affirmed in 1919 when, in the Initiatives and Referendums Reference, a Manitoba act providing for direct legislation by way of initiatives and referendums was ruled unconstitutional by the Privy Council on the grounds that a provincial viceroy (even one advised by responsible ministers) could not permit "the abrogation of any power which the Crown possesses through a person directly representing it".[nb 11] Social and technological changes also worked their way into constitutional authority; the Radio Reference found that federal jurisdiction extended to broadcasting,[nb 12] and the Aeronautics Reference found the same for aeronautics.[nb 13]

In 1926, the King–Byng Affair resulted in a constitutional crisis which was the impetus for changes in the relationship between the governor general and the prime minister. Although its key aspects were political in nature, its constitutional aspects continue to be debated.[8] One result was the Balfour Declaration issued later that year, whose principles were eventually codified in the Statute of Westminster 1931. It, and the repeal of the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865, gave the federal parliament the ability to make extraterritorial laws and abolish appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Criminal appeals were abolished in 1933,[na 1] but civil appeals continued until 1949.[na 2] The last Privy Council ruling of constitutional significance occurred in 1954, in Winner v. S.M.T. (Eastern) Limited.[nb 14] After that, the Supreme Court of Canada became the final court of appeal.

In 1937, Lieutenant Governor of Alberta John C. Bowen refused to give Royal Assent to three Legislative Assembly of Alberta bills. Two would have put the province's banks under the control of the provincial government; the third, the Accurate News and Information Act, would have forced newspapers to print government rebuttals to stories the provincial cabinet considered "inaccurate". All three bills were later declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of Canada in Reference re Alberta Statutes, which was upheld by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.[nb 15]

World War II's broader scope required passage of the National Resources Mobilization Act to supplement the powers in the War Measures Act to pursue the national war effort. The extent to which wartime federal power could expand was further clarified in the Chemicals Reference (which held that Orders in Council under the War Measures Act were equivalent to acts of parliament)[nb 16] and the Wartime Leasehold Regulations Reference, which held that wartime regulations could displace provincial jurisdiction for the duration of an emergency.[nb 17] Additional measures were required in order to secure control of the economy during that time. Jurisdiction over unemployment insurance was transferred permanently to the federal sphere;[na 3] the provinces surrendered their power to levy succession duties and personal and corporate income taxes for the duration of the war (and for one year afterwards) under the Wartime Tax Rental Agreement;[9] and labour relations were centralized under federal control with the Wartime Labour Relations Regulations (lasting until 1948), in which the provinces ceded their jurisdiction over all labour issues.[10]

Canada emerged from the war with better cooperation between the federal and provincial governments. This led to a welfare state, a government-funded health care system and the adoption of Keynesian economics. In 1951 section 94A was added to the British North America Act, 1867 to allow the Canadian parliament to provide for pensions.[na 4] This was extended in 1964 to allow supplementary benefits, including disability and survivors' benefits.[na 5] The era saw an increase in First Ministers' Conferences to resolve federal-provincial issues. The Supreme Court of Canada became the court of final appeal after the 1949 abolition of appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council and the federal parliament received the power to amend the constitution, limited to non-provincial matters and subject to other constraints.[na 6]

1960–1982

1961 saw the last instance of a lieutenant governor reserving a bill passed by a provincial legislature. Frank Lindsay Bastedo, Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan, withheld Royal Assent and reserved Bill 5, An Act to Provide for the Alteration of Certain Mineral Contracts, to the Governor-in-Council for review. According to Bastedo, "[T]his is a very important bill affecting hundreds of mineral contracts. It raises implications which throw grave doubts of the legislation being in the public interest. There is grave doubt as to its validity". The act was upheld in an Order in Council by the federal government.[11][na 7]

Parliament passed the Canadian Bill of Rights, the first codification of rights by the federal government. Prime Minister Lester Pearson obtained passage of major social programs, including universal health care (a federal-provincial cost-sharing program), the Canada Pension Plan and Canada Student Loans. Quebec's Quiet Revolution encouraged increased administrative decentralization in Canada, with Quebec often opting out of federal initiatives and instituting its own (such as the Quebec Pension Plan). The Quebec sovereignty movement led to the victory of the Parti Québécois in the 1976 Quebec election, prompting consideration of further loosening ties with the rest of Canada; this was rejected in a 1980 referendum.

During the premiership of Pierre Trudeau, the federal government became more centralist. Canada experienced "conflictual federalism" from 1970 to 1984, generating tensions with Quebec and other provinces. The National Energy Program and other petroleum disputes sparked bitterness in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland toward the federal government.[12]

Patriation

Although Canada achieved full status as a sovereign nation in the Statute of Westminster 1931, there was no consensus on a process to amend the constitution; attempts such as the 1965 Fulton–Favreau formula and the 1971 Victoria Charter failed to receive unanimous approval from both levels of government. When negotiations with the provinces again stalled in 1980, Trudeau threatened to take the case for patriation to the British parliament "[without] bothering to ask one premier". According to the federal cabinet and Crown counsel, if the British Crown (in council, in parliament, and on the bench) exercised sovereignty over Canada, it would do so only at the request of the federal ministers.[13]

Manitoba, Newfoundland and Quebec posed reference questions to their respective courts of appeal, in which five other provinces intervened in support. In his ruling, Justice Joseph O'Sullivan of the Manitoba Court of Appeal held that the federal government's position was incorrect; the constitutionally-entrenched principle of responsible government meant that "Canada had not one responsible government but eleven."[13] Officials in the United Kingdom indicated that the British parliament was under no obligation to fulfill a request for legal changes desired by Trudeau, particularly if Canadian convention was not followed.[14] All rulings were appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada. In a decision later known as the Patriation Reference, the court ruled that such a convention existed but did not prevent the federal parliament from attempting to amend the constitution without provincial consent and it was not the role of the courts to enforce constitutional conventions.

The Canadian parliament asked the British parliament to approve the Constitution Act, 1982, which it did in passage of the Canada Act 1982. This resulted in the introduction of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the transfer of constitutional amendment to a Canadian framework and the addition of section 92A to the Constitution Act, 1867, giving the provinces more jurisdiction over their natural resources.

After 1982

The Progressive Conservative Party under Joe Clark and Brian Mulroney favoured the devolution of power to the provinces, culminating in the failed Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords. After merging in 2003 with the heavily devolutionist Canadian Alliance, the Conservative Party under Stephen Harper has maintained the same stance. When Harper was appointed prime minister in 2006, the frequency of First Ministers' conferences declined significantly; inter-provincial cooperation increased with meetings of the Council of the Federation, established by the provincial premiers, in 2003.

After the 1995 Quebec referendum on sovereignty, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien limited the ability of the federal government to spend money in areas under provincial jurisdiction. In 1999 the federal government and all provincial governments except Quebec's agreed to the Social Union Framework Agreement, which promoted common standards for social programmes across Canada.[15] Former Prime Minister Paul Martin used the phrase "asymmetrical federalism" to describe this arrangement.[16][17] The Supreme Court upholds the concepts of flexible federalism (where jurisdictions overlap) and cooperative federalism (where they can favourably interact),[18] as noted in Reference re Securities Act.

The Crown

As a federal monarchy, the Canadian Crown is present in all jurisdictions in the country,[nb 18] with the headship of state a part of all equally.[19] Sovereignty is conveyed not by the governor general or federal parliament, but through the Crown itself as a part of the executive, legislative and judicial branches of Canada's 11 (one federal and 10 provincial) legal jurisdictions; linking the governments into a federal state,[20] the Crown is "divided" into 11 "crowns".[21] The fathers of the Canadian Confederation viewed the constitutional monarchy as a bulwark against potential fracturing of the Canadian federation,[22] and the Crown remains central to Canadian federalism.[23]

.jpg.webp)

The Senate

The Senate The House of Commons

The House of Commons

Distribution of legislative powers

Division of powers

The federal-provincial distribution of legislative powers (also known as the division of powers) defines the scope of the federal and provincial legislatures. These have been identified as exclusive to the federal or provincial jurisdictions or shared by all. Section 91 of the Constitution Act, 1867, lists the major federal parliament powers, based on the concepts of peace, order, and good government; while Section 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867 enumerates those of the provincial governments.

The Act puts remedial legislation on education rights, uniform laws relating to property and civil rights (in all provinces other than Quebec), creation of a general court of appeal and other courts "for the better Administration of the Laws of Canada," and implementing obligations arising from foreign treaties, all under the purview of the federal legislature in Section 91. Some aspects of the Supreme Court of Canada were elevated to constitutional status in 1982.[nb 19]

The Act lists the powers of the provincial parliaments (subject to the federal parliament's authority to regulate inter-provincial movement) in Section 92. These powers include the exploration, development and export to other provinces of non-renewable natural resources, forestry resources and electrical energy. Education is under provincial jurisdiction, subject to the rights of separate schools.

Old-age pensions, agriculture and immigration are shared by federal and provincial jurisdictions. One prevails over the other in cases of conflict, however: for pensions, federal legislation will not displace provincial laws, and for agriculture and immigration it is the reverse.

The Constitution Act, 1871 allowed parliament to govern any territories not forming part of any province, and the Statute of Westminster 1931, gave parliament the ability to pass extraterritorial laws.

Doctrines

To rationalize how each jurisdiction may use its authority, certain doctrines have been devised by the courts: pith and substance, including the nature of any ancillary powers and the colourability of legislation; double aspect; paramountcy; inter-jurisdictional immunity; the living tree; the purposive approach; and charter compliance (most notably through the Oakes test). Additionally, there is the implied Bill of Rights.

Jurisdiction over public property

Jurisdiction over Crown property is divided between the provincial legislatures and the federal parliament, with the key provisions Sections 108, 109, and 117 of the Constitution Act, 1867. Public works are the property of the federal Crown, and natural resources are within the purview of the provinces.[nb 20] Title to such property is not vested in one jurisdiction or another, however, since the Canadian Crown is indivisible.[24][25] Section 109 has been given a particularly-broad meaning;[26] provincial legislation regulating labour used to harvest and the disposal of natural resources does not interfere with federal trade and commerce power,[nb 21][27][nb 22][27] and royalties have been held to cover the law relating to escheats.[nb 23] Canada cannot unilaterally create Indian reserves, since the transfer of such lands requires federal and provincial approval by Order in Council (although discussion exists about whether this is sound jurisprudence).[26][nb 24]

The provincial power to manage Crown land did not initially extend to Manitoba, Alberta and Saskatchewan when they were created from part of the Northwest Territories, since the land was vested in the federal Crown. It was vacated on some land (the Railway Belt and the Peace River Block) by British Columbia when it entered the confederation. Title to this land was not vested in those provinces until the passage of the Natural Resources Acts in 1930. The power is not absolute, however; provincial Crown land may be regulated or expropriated for federal purposes.[nb 25][nb 26] The administration of crown land is also subject to the rights of First Nations[nb 27] (since they are a relevant interest),[nb 28] and provincial power "is burdened by the Crown obligations toward the Aboriginal people in question".[nb 29] Debate exists about whether such burdens apply in the same manner in the Western provinces under the Natural Resources Acts.[28]

Management of offshore resources is complex; although management of the beds of internal waters is vested in the provincial Crowns, management of beds of territorial seas is vested in the federal Crown (with management of the continental shelf and the exclusive economic zone).[nb 30][nb 31][29] The beds and islands of the waters between Vancouver Island and mainland British Columbia have been declared the property of the Crown in right of British Columbia.[nb 32] Federal-provincial management agreements have been implemented concerning offshore petroleum resources in the areas around Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova Scotia.[na 8][na 9]

Taxation and spending

Taxation is a power of the federal and provincial legislatures; provincial taxation is more restricted, in accordance with sections 92(2) and 92(9) of the Constitution Act, 1867. In Allard Contractors Ltd. v. Coquitlam (District), provincial legislatures may levy an indirect fee as part of a valid regulatory scheme.[nb 33] Gérard La Forest observed obiter dicta that section 92(9) (with provincial powers over property and civil rights and matters of a local or private nature) allows for the levying of license fees even if they constitute indirect taxation.[30]

Parliament has the power to spend money on public debt and property. Although the Supreme Court of Canada has not ruled directly about constitutional limits on federal spending power,[nb 34][31] parliament can transfer payments to the provinces.[lower-alpha 3] This arises from the 1937 decision of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council on the Unemployment Insurance Reference, where Lord Atkin observed: "Assuming the Dominion has collected by means of taxation a fund, it by no means follows that any legislation which disposes of it is necessarily within Dominion competence ... If on the true view of the legislation it is found that in reality in pith and substance the legislation invades civil rights within the Province, or in respect of other classes of subjects otherwise encroaches upon the provincial field, the legislation will be invalid".[nb 36] In Re Canada Assistance Plan, Justice Sopinka held that the withholding of federal money previously granted to fund a matter within provincial jurisdiction does not amount to the regulation of that matter.[nb 37]

Federal legislative power

Much distribution of power has been ambiguous, leading to disputes which have been decided by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council and (after 1949) the Supreme Court of Canada. The nature of the Canadian constitution was described by the Privy Council in 1913 as not truly federal (unlike the United States and Australia); although the British North America Act, 1867, states in its preamble that the colonies had expressed "their desire to be federally united into one Dominion", "the natural and literal interpretation of the word [federal] confines its application to cases in which these States, while agreeing on a measure of delegation, yet in the main continue to preserve their original Constitutions". The Privy Council determined that the Fathers of Confederation desired a "general Government charged with matters of common interest, and new and merely local Governments for the Provinces". Matters other than those listed in the British North America Act, 1867, as the responsibility of the federal or provincial parliaments fell to the federal legislature (the reverse of the arrangement between the federal and state congresses in the United States).[nb 38]

National and provincial concerns

The preamble of Section 91 of the Constitution Act, 1867 states: "It shall be lawful for the Queen ... to make laws for the Peace, Order, and good Government of Canada, in relation to all Matters not coming within the Classes of Subjects by this Act assigned exclusively to the Legislatures of the Provinces". In addition to assigning powers not stated elsewhere (which has been narrowly interpreted), this has led to the creation of the national-emergency and national-concern doctrines.

The national-emergency doctrine was described by Mr Justice Beetz in Reference re Anti-Inflation Act.[nb 39][lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5] The national-concern doctrine is governed by the principles stated by Mr Justice Le Dain in R. v. Crown Zellerbach Canada Ltd..[nb 41][lower-alpha 6]

The federal government is partially limited by powers assigned to the provincial legislatures; for example, the Canadian constitution created broad provincial jurisdiction over direct taxation and property and civil rights. Many disputes between the two levels of government revolve around conflicting interpretations of the meaning of these powers.

In the Local Prohibition Case of 1896, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council arrived at a method of interpretation, known as the "four-departments doctrine", in which jurisdiction over a matter is determined in the following order:[nb 42]

- Does it fall under Section 92, classes 1–15?

- Can it be characterized as falling under Section 91, classes 1–29?

- Is it of a general nature, bringing it within Section 91's residuary clause?

- If not, it falls under Section 92, class 16.[32]

By the 1930s, as noted in the Fish Canneries Reference and Aeronautics Reference, the division of responsibilities between federal and provincial jurisdictions was summarized by Lord Sankey.[lower-alpha 7]

Although the Statute of Westminster 1931 declared that the Parliament of Canada had extraterritorial jurisdiction, the provincial legislatures did not achieve similar status. According to s. 92, "In each Province the Legislature may exclusively make Laws ...".

If a provincial law affects the rights of individuals outside the province:

- If it is, in pith and substance, provincial, ancillary effects on the rights of individuals outside the province are irrelevant[nb 43] but

- Where it is, in pith and substance, legislation in relation to the rights of individuals outside the province, it will be ultra vires the province[nb 5][nb 44]

In The Queen (Man.) v. Air Canada, it was held that the s. 92(2) power providing for "direct taxation within the province" does not extend to taxing sales on flights passing over (or through) a province, but the question of how far provincial jurisdiction can extend into a province's airspace was left undecided.[nb 45] However, the property and civil rights power does allow for determining rules with respect to conflict of laws in civil matters.[na 10]

National dimension

Federal jurisdiction arises in several circumstances:

- Under the national-emergency doctrine for temporary legislation (the War Measures Act)

- Under the national-concern doctrine for:

- Matters not existing at confederation (radio and television)

- Matters of a local or private nature in a province which have become matters of national concern, such as what can accrue to the regulation of trade and commerce

- Matters where the grant is exclusive under Section 91 (criminal law)

- Matters where authority may be assumed (as with works for the general advantage of Canada)

The gap approach, employed sparingly, identifies areas of jurisdiction arising from oversights by the drafters of the constitution; for example, federal jurisdiction to incorporate companies is inferred from the power provinces have under Section 92 for "The Incorporation of Companies with Provincial Objects".

Uniformity of federal law

Section 129 of the Constitution Act, 1867 provided for laws in effect at the time of Confederation to continue until repealed or altered by the appropriate legislative authority. Similar provisions were included in the terms of union of other territories that were subsequently incorporated into Canada.

The uniformity of laws in some areas of federal jurisdiction was significantly delayed. Offences under the Criminal Code were not made uniform until 1892, when common-law criminal offences were abolished.[33] Divorce law was not made uniform until 1968, Canadian maritime law not until 1971 and marriage law not until 2005. Provisions of the Civil Code of Lower Canada, adopted in 1865 by the former Province of Canada, affecting federal jurisdiction continued to be in force in Quebec (if they had not been displaced by other federal Acts) until their repeal on 15 December 2004.[na 11][34]

Interplay of jurisdictions

According to the Supreme Court of Canada, "our Constitution is based on an allocation of exclusive powers to both levels of government, not concurrent powers, although these powers are bound to interact in the realities of the life of our Constitution."[nb 46] Chief Justice Dickson observed the complexity of that interaction:

The history of Canadian constitutional law has been to allow for a fair amount of interplay and indeed overlap between federal and provincial powers. It is true that doctrines like interjurisdictional and Crown immunity and concepts like "watertight compartments" qualify the extent of that interplay. But it must be recognized that these doctrines and concepts have not been the dominant tide of constitutional doctrines; rather they have been an undertow against the strong pull of pith and substance, the aspect doctrine and, in recent years, a very restrained approach to concurrency and paramountcy issues.[nb 47]

Notable examples include:

- Although the provinces have the power to create criminal courts, only the federal government has the power to determine criminal procedure. Criminal procedure includes prosecution, and federal law can determine the extent of federal and provincial involvement.[nb 48] The provinces' power under s. 92(14) over the administration of justice includes the organization of courts and police forces, which determines the level of law enforcement. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police, as the federal police, contracts for the provision of many provincial and municipal police forces.

- Although the federal power to regulate fisheries does not override provincial authority to require a permit for catching fish in waters under provincial control,[nb 49] the regulation of recreational fisheries has been partially delegated under the Fisheries Act[na 12] to the provinces for specified species in specific provinces.[na 13]

- Works affecting navigation are subject to federal approval under the Navigable Waters Protection Act[35] and provincial approval, since the beds of navigable waters are generally reserved to the Crown in right of the province.[36][37][38]

- Although federal jurisdiction over broadcasting and most telecommunications is exclusive, the provinces may regulate advertising[nb 50] and cable installation (above or underground).[nb 51][39]

- Although the concept of marriage is under federal jurisdiction, the solemnization of marriages is controlled by the provinces.

- The provincial power to regulate security interests under the property and civil-rights power will be displaced by security interests created under a federal head of power – most notably under the banking power – but only to the extent that federal law has covered the field.[nb 52]

- Laws arising from the property and civil-rights power will be used to complement the interpretation of federal legislation where the federal Act has not provided otherwise, but federal power cannot be used to create rules of private law in areas outside its jurisdiction.[nb 53][na 14]

- In insolvency law, provincial statutes operate by federal incorporation into the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act and the Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act. However, where a stay under federal law has been lifted in order to allow proceedings to take place, a province can impose a moratorium on proceedings falling under provincial law.[nb 54]

Delegation and cooperation

In 1899, Lord Watson asserted during the argument in CPR v Bonsecours[nb 55] that neither the federal parliament nor the provincial legislatures could give legislative authority to the other level.[40] Subsequent attempts to dovetail federal and provincial legislation to achieve certain ends met with difficulty, such as an attempt by Saskatchewan to ensure enforcement of a federal statute[na 15] by enacting a complementary Act[na 16] declaring that the federal Act would continue in force under provincial authority if it was ruled ultra vires. The Saskatchewan Court of Appeal ruled a federal and provincial Act ultra vires, voiding both as an attempt by the province to vest powers in parliament unauthorized by the BNA Act.[41][nb 56]

The matter was addressed in 1950 by the Supreme Court,[42] which held ultra vires a proposed Nova Scotia Act which would have authorized the inter-delegation of legislative and taxation authority between Parliament and the Nova Scotia legislature.[nb 57] In that decision, Justice Rand explained the distinction between delegation to a subordinate body and that to a legislative body.[lower-alpha 8]

Later attempts to achieve federal-provincial coordination have succeeded with other types of legislative schemes[43] involving:

- Conditional legislation (such as a federal Act, providing that it will not apply where a provincial Act has been enacted in a given matter). As Justice Rand declared in 1959, "That Parliament can so limit the operation of its own legislation and that it may do so upon any such event or condition is not open to serious debate".[nb 58]

- Incorporation by reference or adoption (for example, a federal regulation prohibiting vehicles from operating on a federal highway except "in accordance with the laws of the province and the municipality in which the highway is situated")[na 17]

- Joint schemes with administrative cooperation, such as the administrative authority granted by federal law to provincial transport boards to license extraprovincial transport[na 18]

Power to implement treaties

To understand how treaties can enter Canadian law, three significant cases must be considered: the Aeronautics Reference, the Radio Reference and the Labour Conventions Reference.[nb 59] Although the reasoning behind the judgments is complex,[44] it is considered to break down as follows:

- Aeronautics were held by the Aeronautics Reference to be within the authority of the Parliament of Canada under s. 132 governing treaties entered into by the British Empire. After that treaty was replaced, it was held in Johannesson v. West St. Paul that in accordance with Ontario v. Canada Temperance Federation the field continued to be within federal jurisdiction under the power relating to peace, order and good government.

- Although an international agreement governing broadcasting was not a treaty of the British Empire, the Radio Reference held that it fell within federal jurisdiction; Canada's obligations under its agreements in this field required it to pass legislation applying to all Canadian residents, and the matter could be seen as analogous to telegraphs (already in the federal sphere).

- The Labour Conventions Reference dealt with labour relations (clearly within provincial jurisdiction); since the conventions were not treaties of the British Empire and no plausible argument could be made for the field attaining a national dimension or becoming of national concern, the Canadian Parliament was unable to exercise new legislative authority.

Although the Statute of Westminster 1931 had made Canada fully independent in governing its foreign affairs, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council held that s. 132 did not evolve to take that into account. As noted by Lord Atkin at the end of the judgment,

It must not be thought that the result of this decision is that Canada is incompetent to legislate in performance of treaty obligations. In totality of legislative powers, Dominion and Provincial together, she is fully equipped. But the legislative powers remain distributed and if in the exercise of her new functions derived from her new international status she incurs obligations they must, so far as legislation be concerned when they deal with provincial classes of subjects, be dealt with by the totality of powers, in other words by co-operation between the Dominion and the Provinces. While the ship of state now sails on larger ventures and into foreign waters she still retains the watertight compartments which are an essential part of her original structure.

This case left undecided the extent of federal power to negotiate, sign and ratify treaties dealing with areas under provincial jurisdiction, and has generated extensive debate about complications introduced in implementing Canada's subsequent international obligations;[45][46] the Supreme Court of Canada has indicated in several dicta that it might revisit the issue in an appropriate case.[47]

Limits on legislative power

Outside the questions of ultra vires and compliance with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, there are absolute limits on what the Parliament of Canada and the provincial legislatures can legislate. According to the Constitution Act, 1867:

- S. 96 has been construed to hold that neither the provincial legislatures nor Parliament can enact legislation removing part of the inherent jurisdiction of the superior courts.[nb 60]

- S. 121 states, "All Articles of the Growth, Produce, or Manufacture of any one of the Provinces shall, from and after the Union, be admitted free into each of the other Provinces". This amounts to a prohibition of inter-provincial tariffs.

- S. 125 states, "No Lands or Property belonging to Canada or any Province shall be liable to Taxation".

- Under s. 129, limits have been placed on the ability of the legislatures of Ontario and Quebec to amend or repeal Acts of the former Province of Canada. Where such an act created a body corporate operating in the former Province, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council held that such bodies cannot have "provincial objects" and only the Parliament of Canada had power to deal with such acts.[nb 61] It has been held that this restriction exists for any Act applying equally to Upper and Lower Canada,[lower-alpha 9] which became problematic when the Civil Code of Lower Canada was replaced by the Civil Code of Quebec.[50]

While the Parliament of Canada has the ability to bind the Crown in right of Canada or of any province, the converse is not true for the provincial legislatures, as "[p]rovincial legislation cannot proprio vigore [ie, of its own force] take away or abridge any privilege of the Crown in right of the Dominion."[nb 63]

Notes

- ↑ The federal regulation of trade and commerce was circumscribed by the provincial property and civil rights power as a result of Citizen's Insurance Co. v. Parsons,[nb 1] disallowance and reservation of provincial statutes was curtailed as a political consequence of McLaren v. Caldwell,[nb 2][5] and the double aspect doctrine was introduced into Canadian jurisprudence via Hodge v. The Queen.[nb 3] Not all rulings, however, went in the provinces' favour. Russell v. The Queen established the right of the federal parliament to make laws applicable in the provinces if those laws relate to a concern that exists in all jurisdictions of the country[nb 4] and in Royal Bank of Canada v. The King the provinces were held not to possess the power to affect extraprovincial contract rights.[nb 5] Pith and substance, used to determine under which crown a given piece of legislation falls, was introduced in Cushing v. Dupuy.[nb 6]

- ↑ The Board of Commerce case affirmed that only a national emergency warranted the curtailment of citizens' rights by the federal parliament,[nb 7] subsequently reaffirmed by Fort Frances Pulp and Paper v. Manitoba Free Press,[nb 8] and was held to even include amending Acts of Parliament through regulations.[nb 9] However, Toronto Electric Commissioners v. Snider,[nb 10] held that such emergencies could not be used to unreasonably intrude on the provinces' property and civil rights power.

- ↑ The Alberta Court of Appeal in Winterhaven Stables Limited v. Canada (Attorney General) characterized that as possessing the following nature: "[The federal parliament] is entitled to spend the money that it raises through proper exercise of its taxing power in the manner that it chooses to authorize. It can impose conditions on such disposition so long as the conditions do not amount in fact to a regulation or control of a matter outside federal authority. The federal contributions are now made in such a way that they do not control or regulate provincial use of them. As well there are opting out arrangements that are available to those provinces who choose not to participate in certain shared-cost programs.[nb 35]

- ↑ "But if one looks at the practical effects of the exercise of the emergency power, one must conclude that it operates so as to give to Parliament for all purposes necessary to deal with the emergency, concurrent and paramount jurisdiction over matters which would normally fall within exclusive provincial jurisdiction. To that extent, the exercise of that power amounts to a temporary pro tanto amendment of a federal Constitution by the unilateral action of Parliament. The legitimacy of that power is derived from the Constitution: when the security and the continuation of the Constitution and of the nation are at stake, the kind of power commensurate with the situation 'is only to be found in that part of the Constitution which establishes power in the State as a whole'."[nb 40]

- ↑ "The extraordinary nature and the constitutional features of the emergency power of Parliament dictate the manner and form in which it should be invoked and exercised. It should not be an ordinary manner and form. At the very least, it cannot be a manner and form which admits of the slightest degree of ambiguity to be resolved by interpretation. In cases where the existence of an emergency may be a matter of controversy, it is imperative that Parliament should not have recourse to its emergency power except in the most explicit terms indicating that it is acting on the basis of that power. Parliament cannot enter the normally forbidden area of provincial jurisdiction unless it gives an unmistakable signal that it is acting pursuant to its extraordinary power. Such a signal is not conclusive to support the legitimacy of the action of Parliament but its absence is fatal."

- ↑

- The national concern doctrine is separate and distinct from the national emergency doctrine of the peace, order and good government power, which is chiefly distinguishable by the fact that it provides a constitutional basis for what is necessarily legislation of a temporary nature;

- The national concern doctrine applies to both new matters which did not exist at Confederation and to matters which, although originally matters of a local or private nature in a province, have since, in the absence of national emergency, become matters of national concern;

- For a matter to qualify as a matter of national concern in either sense it must have a singleness, distinctiveness and indivisibility that clearly distinguishes it from matters of provincial concern and a scale of impact on provincial jurisdiction that is reconcilable with the fundamental distribution of legislative power under the Constitution;

- In determining whether a matter has attained the required degree of singleness, distinctiveness and indivisibility that clearly distinguishes it from matters of provincial concern it is relevant to consider what would be the effect on extra‑provincial interests of a provincial failure to deal effectively with the control or regulation of the intra‑provincial aspects of the matter.

- ↑ Aeronautics Reference at p. 8: # The legislation of the Parliament of the Dominion, so long as it strictly relates to subjects of legislation expressly enumerated in section 91, is of paramount authority, even if it trenches upon matters assigned to the Provincial Legislature by section 92.

- The general power of legislation conferred up on the Parliament of the Dominion by section 91 of the act in supplement of the power to legislate upon the subjects expressly enumerated must be strictly confined to such matters as are unquestionably of national interest and importance, and must not trench on any of the subjects enumerated in section 92, as within the scope of Provincial legislation, unless these matters have attained such dimensions as to affect the body politic of the Dominion.

- It is within the competence of the Dominion Parliament to provide for matters which though otherwise within the legislative competence of the Provincial Legislature, are necessarily incidental to effective legislation by the Parliament of the Dominion upon a subject of legislation expressly enumerated in section 91.

- There can be a domain in which Provincial and Dominion legislation may overlap, in which case, neither legislation will be ultra vires if the field is clear, but if the field is not clear and the two legislations meet, the Dominion legislation must prevail.

- ↑ "In the generality of actual delegation to its own agencies, Parliament, recognizing the need of the legislation, lays down the broad scheme and indicates the principles, purposes and scope of the subsidiary details to be supplied by the delegate: under the mode of enactment now being considered, the real and substantial analysis and weighing of the political considerations which would decide the actual provisions adopted, would be given by persons chosen to represent local interests. Since neither is a creature nor a subordinate body of the other, the question is not only or chiefly whether one can delegate, but whether the other can accept. Delegation implies subordination and in Hodge v. The Queen, the following observations ... appear: Within these limits of subjects and area the local legislature is supreme, and has the same authority as the Imperial Parliament, or the parliament of the Dominion, would have had under like circumstances to confide to a municipal institution or body of its own creation authority to make by-laws or resolutions as to subjects specified in the enactment, and with the object of carrying the enactment into operation and effect.... It was argued at the bar that a legislature committing important regulations to agents or delegates effaces itself. That is not so. It retains its powers intact, and can, whenever it pleases, destroy the agency it has created and set up another, or take the matter directly into his own hands. How far it shall seek the aid of subordinate agencies, and how long it shall continue them, are matters for each legislature, and not for Courts of Law, to decide."

- ↑ Ex parte O'Neill, RJQ 24 SC 304,[48] where it was held that the Legislative Assembly of Quebec was unable to repeal the Temperance Act, 1864,[na 19] but it could pass a concurrent statute for regulating liquor traffic within the Province.[49] However, it has also been held that the Parliament of Canada could not repeal that Act with respect only to Ontario.[nb 62]

References

- ↑ Banting, Keith G.; Simeon, Richard (1983). And no one cheered: federalism, democracy, and the Constitution Act. Toronto: Methuen. pp. 14, 16. ISBN 0-458-95950-2.

- ↑ "Biography – MACDONALD, Sir JOHN ALEXANDER – Volume XII (1891-1900) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ↑ "John A. Macdonald on the Federal System". The Historica-Dominion Institute. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2012., quoting Parliamentary Debates on the Subject of the Confederation of the British North American Provinces—3rd Session, 8th Provincial Parliament of Canada. Quebec: Hunter, Rose & Co. 1865. pp. 29–45.

- ↑ Romney 1999, pp. 100–102.

- ↑ Lamot 1998, p. 125.

- ↑ Romney, Paul (1986). Mr Attorney: The Attorney-General for Ontario in court, cabinet and legislature, 1791-1899. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 240–281.

- ↑ Edward Blake (1888). The St. Catharine's Milling and Lumber Company v. the Queen: Argument of Mr. Blake, of counsel for Ontario. Toronto: Press of the Budget. p. 6. ISBN 9780665001642.

- ↑ Forsey, Eugene (1 October 2010), Forsey, Helen (ed.), "As David Johnson Enters Rideau Hall...", The Monitor, Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, retrieved 8 August 2012

- ↑ Bélanger, Claude. "Canadian federalism, the Tax Rental Agreements of the period of 1941–1962 and fiscal federalism from 1962 to 1977". Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ↑ "Ontario Labour Relations Board: History". Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ↑ Mallory, J. R. (1961). "The Lieutenant-Governor's Discretionary Powers: The Reservation of Bill 56". Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science. 27 (4): 518–522. doi:10.2307/139438. JSTOR 139438.

- ↑ Dyck 2012, pp. 416–420

- 1 2 Romney 1999, pp. 273–274

- ↑ Heard, Andrew (1990). "Canadian Independence". Vancouver: Simon Fraser University. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ↑ Noël, Alain (November 1998). "The Three Social Unions" (PDF). Policy Options (in French). Institute for Research on Public Policy. 19 (9): 26–29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ "Flexible federalism". The Free Library. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ↑ Douglas Brown (July 2005). "Who's afraid of Asymmetrical Federalism?". Optimum Online. 35 (2): 2 et seq. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ↑ Hunter, Christopher. "Cooperative Federalism & The Securities Act Reference: A Rocky Road". The Court. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ↑ Roberts, Edward (2009). "Ensuring Constitutional Wisdom During Unconventional Times" (PDF). Canadian Parliamentary Review. Ottawa: Commonwealth Parliamentary Association. 23 (1): 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- ↑ MacLeod, Kevin S. (2012), A Crown of Maples (PDF) (2012 ed.), Ottawa: Department of Canadian Heritage, p. 17, ISBN 978-1-100-20079-8, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2016, retrieved 23 August 2012

- ↑ Jackson, Michael D. (2003). "Golden Jubilee and Provincial Crown" (PDF). Canadian Monarchist News. Toronto: Monarchist League of Canada. 7 (3): 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- ↑ Smith, David E. (1995). The Invisible Crown. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-8020-7793-5.

- ↑ Smith, David E. (10 June 2010), The Crown and the Constitution: Sustaining Democracy? (PDF), Kingston: Queen's University, p. 6, archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2013, retrieved 18 May 2010

- ↑ Romney 1999, p. 274.

- ↑ Cabinet Secretary and Clerk of the Executive Council (April 2004), Executive Government Processes and Procedures in Saskatchewan: A Procedures Manual (PDF), Regina: Queen's Printer for Saskatchewan, p. 10, retrieved 30 July 2009

- 1 2 Bowman, Laura. "Constitutional "Property" and Reserve Creation: Seybold Revisited" (PDF). Manitoba Law Journal. University of Manitoba, Robson Hall Faculty of Law. 32 (1): 1–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- 1 2 Hogg 2007, par. 29.2.

- ↑ Lambrecht, Kirk (30 July 2014). "The Importance of Location and Context to the Future Application of the Grassy Narrows Decision of the Supreme Court of Canada" (PDF). ABlawg.ca.

- ↑ Fisheries and Oceans Canada. "Canada's Ocean Estate – A Description of Canada's Maritime Zones". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 14 June 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ La Forest, G.V. (1981). The Allocation of Taxing Power Under the Canadian Constitution (2nd ed.). Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation. p. 159. ISBN 0-88808006-9.

- ↑ Richer, Karine. "RB 07-36E: The Federal Spending Power". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ↑ for example, Claude Bélanger. "Theories and Interpretation of the Constitution Act, 1867". Marianopolis College. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ↑ Criminal Code, 1892, SC 1892, c 29

- ↑ "Backgrounder: A Third Bill to Harmonize Federal Law with the Civil Law of Quebec". Department of Justice (Canada). Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ↑ "NWPA Regulatory Framework". Transport Canada. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ "Policy PL 2.02.02 – Ownership determinations – Beds of navigable waters" (PDF). Ministry of Natural Resources of Ontario. 26 February 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ "Procedure PL 2.02.02 – Ownership determinations – Beds of navigable waters" (PDF). Ministry of Natural Resources of Ontario. 26 February 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ "Dams, Water Crossings and Channelizations – The Lakes and Rivers Improvement Act". Ministry of Natural Resources of Ontario. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ "Canadian Municipalities and the Regulation of Radio Antennae and their Support Structures — III. An Analysis of Constitutional Jurisdiction in Relation to Radiocommunication". Industry Canada. 6 December 2004. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ↑ La Forest 1975, p. 134.

- ↑ La Forest 1975, p. 135.

- ↑ La Forest 1975, pp. 135–137.

- ↑ La Forest 1975, p. 137–143.

- ↑ Cyr, Hugo (2009). "I – The Labour Conventions Case". Canadian Federalism and Treaty Powers: Organic Constitutionalism at Work. Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang SA. ISBN 978-90-5201-453-1. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ↑ Zagros Madjd-Sadjadi, Winston-Salem State University. "Subnational Sabotage or National Paramountcy? Examining the Dynamics of Subnational Acceptance of International Agreements" (PDF). Southern Journal of Canadian Studies, vol. 2, 1. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ↑ H. Scott Fairley (1999). "External Affairs and the Canadian Constitution". In Yves Le Bouthillier; Donald M. McRae; Donat Pharand (eds.). Selected Papers in International Law: Contribution of the Canadian Council on International Law. London: Kluwer International. pp. 79–91. ISBN 90-411-9764-8.

- ↑ "Canadian Interpretation and Construction of Maritime Conventions". Archived from the original on 9 September 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ↑ Lefroy, Augustus Henry Frazer (1918). A short treatise on Canadian constitutional law. Toronto: The Carswell Company. p. 189.

- ↑ Lefroy, Augustus Henry Frazer (1913). Canada's Federal System. Toronto: The Carswell Company. pp. 162–163.

- ↑ Leclair, Jean (1999). "Thoughts on the Constitutional Problems Raised by the Repeal of the Civil Code of Lower Canada". The Harmonization of Federal Legislation with the Civil Law of the Province of Quebec and Canadian Bijuralism. Ottawa: Department of Justice. pp. 347–394.

Acts and other instruments

- ↑ Criminal Code Amendment Act, S.C. 1932–33, c. 53, s. 17

- ↑ Supreme Court Amendment Act, S.C. 1949 (2nd. session), c. 37, s. 3

- ↑ British North America Act, 1940, 3–4 Geo. VI, c. 36 (U.K.)

- ↑ British North America Act, 1951, 14–15 Geo. VI, c. 32 (U.K.)

- ↑ British North America Act, 1964, 12–13 Eliz. II, c. 73 (U.K.)

- ↑ British North America (No. 2) Act, 1949, 13 Geo. VI, c. 81 (U.K.)

- ↑ "Order in Council P.C. 1961-675", Canada Gazette, 13 May 1961, retrieved 19 August 2012

- ↑ "Canada-Newfoundland Atlantic Accord Implementation Act (S.C. 1987, c. 3)". Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ "Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Resources Accord Implementation Act (S.C. 1988, c. 28)". Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ for example, "Court Jurisdiction and Proceedings Transfer Act, SBC 2003, c. 28". Queen's Printer of British Columbia. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ↑ "Federal Law-Civil Law Harmonization Act, No. 1, S.C. 2001, c. 4, s. 3". Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ↑ "Fisheries Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. F-14)". Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ "Recreational Fishing Regulations". Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 16 November 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ "Interpretation Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. I-21)". 26 February 2015. codifies the general rule at s. 8.1.

- ↑ Live Stock and Live Stock Products Act, R.S.C. 1927, c.120

- ↑ Live Stock and Live Stock Products Act, R.S.S. 1930, c. 151

- ↑ Government Property Traffic Regulations, C.R.C. 1977, c. 887, s. 6(1)

- ↑ Motor Vehicle Transport Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 29 (3rd Supp.), s. 7

- ↑ An Act to amend the laws in force respecting the Sale of Intoxicating Liquors and the issue of Licenses therefor, and otherwise for repression of abuses resulting from such sale, S.C. 1864, c. 18

Case citations

- ↑ The Citizens Insurance Company of Canada and The Queen Insurance Company v Parsons [1881] UKPC 49, (1881) 7 A.C. 96 (26 November 1881), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ Caldwell and another v McLaren [1884] UKPC 21, (1884) 9 A.C. 392 (7 April 1884), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ Hodge v The Queen (Canada) [1883] UKPC 59 at pp. 9–10, 9 App Cas 117 (15 December 1883), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Ontario)

- ↑ Charles Russell v The Queen (New Brunswick) [1882] UKPC 33 at pp. 17–18, [1882] 7 App Cas 829, 8 CRAC 502 (23 June 1882), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Canada)

- 1 2 The Royal Bank of Canada and others v The King and another [1913] UKPC 1a, [1913] A.C. 212 (31 January 1913), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Alberta)

- ↑ Cushing v Dupuy [1880] UKPC 22 at pp. 3–4, (1880) 5 AC 409 (15 April 1880), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Quebec)

- ↑ The Attorney General of Canada v The Attorney General of Alberta and others ("Board of Commerce case") [1921] UKPC 107 at p. 4, [1922] 1 A.C. 191 (8 November 1921), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ The Fort Frances Pulp and Paper Company Limited v The Manitoba Free Press Company Limited and others [1923] UKPC 64 at p. 6, [1923] A.C. 695 (25 July 1923), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Ontario)

- ↑ In Re George Edwin Gray, 1918 CanLII 86 at pp. 167–173, 180–183, 57 SCR 150 (19 July 1918), drawing on R v Halliday [1917] UKHL 1, [1917] AC 260 (1 May 1917)

- ↑ The Toronto Electric Commissioners v Colin G. Snider and others [1925] UKPC 2, [1925] AC 396 (20 January 1925), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Ontario)

- ↑ In the matter of The Initiative and Referendum Act being Chapter 59 of the Acts of Legislative Assembly of Manitoba 6 George V. [1919] UKPC 60, [1919] AC 935 (3 July 1919), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Manitoba)

- ↑ The Attorney General of Quebec v The Attorney General of Canada and others ("Radio Reference") [1932] UKPC 7, [1932] A.C. 304 (9 February 1932), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ The Attorney-General Canada v The Attorney-General of Ontario and others ("Aeronautics Reference") [1931] UKPC 93, [1932] A.C. 54 (22 October 1931), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ Israel Winner (doing business under the name and style of Mackenzie Coach Lines) and others v. S.M.T. (Eastern) Limited and others [1954] UKPC 8 (22 February 1954), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ Attorney General of Alberta v Attorney General of Canada [1938] UKPC 46 (14 July 1938), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ Reference as to the Validity of the Regulations in Relation to Chemicals Enacted by Order in Council and of an Order of the Controller of Chemicals Made Pursuant Thereto (The "Chemicals Reference"), 1943 CanLII 1, [1943] SCR 1 (1 May 1943), Supreme Court (Canada)

- ↑ Reference re Wartime Leasehold Regulations, 1950 CanLII 27, [1950] SCR 124 (1 March 1950), Supreme Court (Canada)

- ↑ Attorney-General of Canada v. Higbie, 1944 CanLII 29, [1945] SCR 385 (23 March 1944), Supreme Court (Canada)

- ↑ Reference re Supreme Court Act, ss. 5 and 6, 2014 SCC 21 (21 March 2014)

- ↑ The Attorney General for the Dominion of Canada v The Attorneys General for the Provinces of Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia ("Fisheries Case") [1898] UKPC 29, [1898] AC 700 (26 May 1898), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ Smylie v. The Queen (1900), 27 O.A.R. 172 (C.A.)

- ↑ Attorney-General for British Columbia and the Minister of Lands v. Brooks-Bidlake and Whitall, Ltd., 1922 CanLII 22, 63 SCR 466 (2 July 1922)

- ↑ The Attorney General of Ontario v Mercer [1883] UKPC 42, [1883] 8 AC 767 (8 July 1883), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ The Ontario Mining Company Limited and The Attorney General for the Dominion of Canada v The Attorney General for the Province of Ontario ("Ontario Mining Co. v. Seybold") [1902] UKPC 46, [1903] AC 73 (12 November 1902) (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ Reference re Waters and Water-Powers, 1929 CanLII 72, [1929] SCR 200 (2 May 1929), Supreme Court (Canada)

- ↑ The Attorney General of Quebec v The Nipissing Central Railway Company and another ("Railway Act Reference") [1926] UKPC 39, [1926] AC 715 (17 May 1926), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ R. v. Sparrow, 1990 CanLII 104, [1990] 1 SCR 1075 (31 May 1990), Supreme Court (Canada)

- ↑ St. Catherines Milling and Lumber Company v The Queen [1888] UKPC 70, [1888] 14 AC 46 (12 December 1888), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ Grassy Narrows First Nation v. Ontario (Natural Resources), 2014 SCC 48 at par. 50 (11 July 2014)

- ↑ Reference Re: Offshore Mineral Rights, 1967 CanLII 71, [1967] SCR 792 (7 November 1967), Supreme Court (Canada)

- ↑ Reference re Newfoundland Continental Shelf, 1984 CanLII 132, [1984] 1 SCR 86 (8 March 1984), Supreme Court (Canada)

- ↑ Reference re: Ownership of the Bed of the Strait of Georgia and Related Areas, 1984 CanLII 138, [1984] 1 SCR 388 (17 May 1984), Supreme Court (Canada)

- ↑ Allard Contractors Ltd. v. Coquitlam (District), CanLII 45, [1993] 4 SCR 371 (18 November 1993)

- ↑ Finlay v. Canada (Minister of Finance), 1993 CanLII 129 at par. 29, [1993] 1 SCR 1080 (25 March 1993)

- ↑ Winterhaven Stables Limited v. Canada (Attorney General), 1988 ABCA 334 at par. 23, 53 DLR (4th) 413 (17 October 1988)

- ↑ The Attorney General of Canada v The Attorney General of Ontario and others [1937] JCPC 7, [1937] AC 355 (28 January 1937) (Canada)

- ↑ Reference Re Canada Assistance Plan (B.C.), 1991 CanLII 74 at par. 93, [1991] 2 SCR 525 (15 August 1991)

- ↑ The Attorney-General for Commonwealth of Australia and others v The Colonial Sugar Refining Company Limited and others [1913] UKPC 76, [1914] AC 237 (17 December 1913), P.C. (on appeal from Australia), and stated again in The Bonanza Creek Gold Mining Company Limited v The King and another [1916] UKPC 11, [1916] 1 AC 566 (24 February 1916), Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ Reference re Anti-Inflation Act, 1976 CanLII 16, [1976] 2 SCR 373 (12 July 1976), Supreme Court (Canada), 463–464

- ↑ Viscount Haldane in Fort Frances, p. 704

- ↑ R. v. Crown Zellerbach Canada Ltd., 1988 CanLII 63 at par. 33, 49 DLR (4th) 161; [1988] 3 WWR 385 (24 March 1988), Supreme Court (Canada)

- ↑ The Attorney General for Ontario v The Attorney General for the Dominion of Canada, and the Distillers and Brewers’ Association of Ontario [1896] UKPC 20, [1896] AC 348 (9 May 1896), P.C. (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ Edgar F. Ladore and others v George Bennett and others [1939] UKPC 33, [1939] 3 D.L.R. 1, [1939] AC. 468 (8 May 1939), P.C. (on appeal from Ontario)

- ↑ Re Upper Churchill Water Rights Reversion Act, 1984 CanLII 17, [1984] 1 SCR 297 (3 May 1984), Supreme Court (Canada)

- ↑ The Queen (Man.) v. Air Canada, 1980 CanLII 16, [1980] 2 SCR 303 (18 July 1980), Supreme Court (Canada)

- ↑ Canadian Western Bank v. Alberta, 2007 SCC 22, [2007] 2 SCR 3 (31 May 2007), par. 32

- ↑ Ontario (Attorney General) v. OPSEU, 1987 CanLII 71, [1987] 2 SCR 2 (29 July 1987) at par. 27

- ↑ Attorney General of Canada v. Canadian National Transportation, Ltd., 1983 CanLII 36, [1983] 2 SCR 206, Supreme Court (Canada)

- ↑ The Attorney General for the Dominion of Canada v The Attorneys General for the Provinces of Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia ("Fisheries Reference") [1898] UKPC 29, [1898] A.C. 700 (26 May 1898), P.C. (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ Attorney General of Quebec v. Kellogg's Co. of Canada, 1978 CanLII 185, [1978] 2 SCR 211 (19 January 1978), Supreme Court (Canada)

- ↑ The Corporation of the City of Toronto v The Bell Telephone Company of Canada [1904] UKPC 71 (11 November 1904), P.C. (on appeal from Ontario)

- ↑ Bank of Montreal v. Innovation Credit Union, 2010 SCC 47, [2010] 3 SCR 3 (5 November 2010)

- ↑ Clark v. Canadian National Railway Co., 1988 CanLII 18, [1988] 2 SCR 680 (15 December 1988)

- ↑ Abitibi Power and Paper Company Limited v Montreal Trust Company and others [1943] UKPC 37, [1943] AC 536 (8 July 1943) (on appeal from Ontario), upholding The Abitibi Power and Paper Company Limited Moratorium Act, 1941, S.O. 1941, c. 1

- ↑ Canadian Pacific Railway Company v The Corporation of the Parish of Notre Dame De Bonsecour [1899] UKPC 22, [1899] AC 367 (24 March 1899), P.C. (on appeal from Quebec)

- ↑ R. v. Zaslavsky, 1935 CanLII 142, [1935] 3 DLR 788 (15 April 1935), Court of Appeal (Saskatchewan, Canada)

- ↑ Attorney General of Nova Scotia v. Attorney General of Canada (the "Nova Scotia Inter-delegation case"), 1950 CanLII 26, [1951] SCR 31 (3 October 1950)

- ↑ Lord's Day Alliance v. Attorney-General of British Columbia, 1959 CanLII 42, [1959] SCR 497 (28 April 1959)

- ↑ The Attorney General of Canada v The Attorney General of Ontario and others ("Labour Conventions Reference") [1937] UKPC 6, [1937] A.C. 326 (28 January 1937), P.C. (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ MacMillan Bloedel Ltd. v. Simpson, 1995 CanLII 57, [1995] 4 SCR 725 (14 December 1995); Re Residential Tenancies Act, 1981 SCC 24, [1981] 1 SCR 714 (28 May 1981); Crevier v. A.G. (Québec) et al., 1981 CanLII 30, [1981] 2 SCR 220 (20 October 1981); Trial Lawyers Association of British Columbia v. British Columbia (Attorney General), 2014 SCC 59 (2 October 2014)

- ↑ Rev. Robert Dobie v The Board for Management of the Presbyterian Church of Canada [1882] UKPC 4, 7 App Cas 136 (21 January 1882), P.C. (on appeal from Quebec)

- ↑ The Attorney General for Ontario v The Attorney General for the Dominion of Canada, and the Distillers and Brewers’ Association of Ontario (The "Local Prohibition Case") [1896] UKPC 20, [1896] AC 348 (9 May 1896), P.C. (on appeal from Canada)

- ↑ per Fitzpatrick CJ, in Gauthier v The King, 1918 CanLII 85 at p. 194, [1918] 56 SCR 176 (5 March 1918), Supreme Court (Canada)

Other sources

- Dyck, Rand (2012). Canadian Politics: Critical Approaches (Concise) (5th ed.). Toronto, Ontario: Nelson Education. ISBN 978-0-17-650343-7. OCLC 669242306.

- Morris J. Fish (2011). "The Effect of Alcohol on the Canadian Constitution ... Seriously" (PDF). McGill Law Journal. 57 (1): 189–209. doi:10.7202/1006421ar. ISSN 1920-6356. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- Hogg, Peter W. (2007). Constitutional Law of Canada (loose-leaf) (5th ed.). Toronto: Carswell. ISBN 978-0-7798-1337-7. ISSN 1914-1262. OCLC 398011547.

- Gérard V. La Forest (1975). "Delegation of Legislative Power in Canada" (PDF). McGill Law Journal. 21 (1): 131–147. ISSN 1920-6356. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- Lamot, Robert Gregory (1998). The Politics of the Judiciary: The S.C.C. and the J.C.P.C. in late 19th Century Ontario (PDF) (M.A.). Carleton University. ISBN 0-612-36831-9.

- J. Noel Lyon (1976). "The Central Fallacy of Canadian Constitutional Law" (PDF). McGill Law Journal. 22 (1): 40–70. ISSN 1920-6356. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- Oliver, Peter C. (2011). "The Busy Harbours of Canadian Federalism: The Division of Powers and Its Doctrines in the McLachlin Court". In Dodek, Adam; Wright, David A. (eds.). Public Law at the McLachlin Court: the First Decade. Toronto, Ontario: Irwin Law. pp. 167–200. ISBN 978-1-55221-214-1. OCLC 774694912.

- Rocher, François; Smith, Miriam (2003). New Trends in Canadian Federalism (2nd ed.). Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press. ISBN 1551114143. OCLC 803829702.

- Romney, Paul (1999). Getting it wrong: how Canadians forgot their past and imperilled Confederation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-8105-3.

- Stevenson, Garth (2003). Unfulfilled union: Canadian federalism and national unity (4th ed.). McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2744-3. OCLC 492159067.

Unfulfilled union: Canadian federalism and national unity.

External links

- Federalism - The canadian encyclopedia

- Federalism in Canada: Basic Framework and Operation

- Federalism-e – published by Queen's University Institute of Intergovernmental Relations

- Canadian Federalism

- Studies on the Canadian Constitution and Canadian Federalism

- Constitutional Law professor Hester Lessard on the Downtown Eastside and Jurisdictional Justice

- Canadian Governments Compared – ENAP

.jpg.webp)