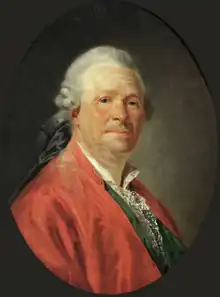

Christoph Willibald (Ritter von) Gluck (German: [ˈkʁɪstɔf ˈvɪlɪbalt ˈɡlʊk]; 2 July 1714 – 15 November 1787) was a composer of Italian and French opera in the early classical period. Born in the Upper Palatinate and raised in Bohemia,[1] both part of the Holy Roman Empire, he gained prominence at the Habsburg court at Vienna. There he brought about the practical reform of opera's dramaturgical practices for which many intellectuals had been campaigning. With a series of radical new works in the 1760s, among them Orfeo ed Euridice and Alceste, he broke the stranglehold that Metastasian opera seria had enjoyed for much of the century. Gluck introduced more drama by using orchestral recitative and cutting the usually long da capo aria. His later operas have half the length of a typical baroque opera. Future composers like Mozart, Schubert, Berlioz and Wagner revered Gluck.

The strong influence of French opera encouraged Gluck to move to Paris in November 1773. Fusing the traditions of Italian opera and the French (with rich chorus) into a unique synthesis, Gluck wrote eight operas for the Parisian stage. Iphigénie en Tauride (1779) was a great success and is often considered to be his finest work. Though he was extremely popular and widely credited with bringing about a revolution in French opera, Gluck's mastery of the Parisian operatic scene was never absolute, and after the poor reception of his Echo et Narcisse (1779), he left Paris in disgust and returned to Vienna to live out the remainder of his life.

Life and career

Ancestry and early years

Gluck's earliest known ancestor is his great-grandfather, Simon Gluckh von Rockenzahn, whose name is recorded in the marriage contract (1672) of his son, the forester Johann (Hans) Adam Gluck (c. 1649–1722) and grandfather of Christoph.[2][3] 'Rockenzahn' is believed to be Rokycany (German: Rokitzan), located in the central part of western Bohemia (about 70 km southwest of Prague and 16 km east of Pilsen).[4] The family name Gluck (also spelled Gluckh, Klugh, Kluch, etc.) likely comes from the Czech word for boy (kluk).[2] In its various spellings, it is repeatedly found in the records of Rokycany.[3] Around 1675 Hans Adam moved to Neustadt an der Waldnaab in the service of Prince Ferdinand August von Lobkowitz, who possessed extensive landholdings in Bohemia as well as the county of Störnstein-Neustadt in the Upper Palatinate.[2][3]

Gluck's father, Alexander, was born in Neustadt an der Waldnaab on 28 October 1683,[5] one of four sons of Hans Adam Gluck who became foresters or gamekeepers.[6] Alexander served in a contingent of about 50 soldiers under Philipp Hyazinth von Lobkowitz, the son of Ferdinand August von Lobkowitz, during the War of Spanish Succession,[7] and, according to Gluck family tradition, rose to the level of gunbearer to the great general of the imperial forces, Eugene of Savoy.[8] In 1711 Alexander settled outside Berching as a forester and hunter in the service of the monastery Seligenporten, Plankstetten Abbey, and the mayors of Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz.[9] He took the vacant position of hunter in Erasbach in 1711 or 1712 (his predecessor had been found shot in the forest).[10]

About Gluck's mother, Maria Walburga, almost nothing is known, including her surname, but she probably grew up in the same area as she was named after Saint Walburga, the sister of Saint Willibald, the first bishop of nearby Eichstätt.[9] The couple probably married around 1711.[2] In 1713 Alexander built a house in Erasbach and by 12 September had taken possession of it.[12]

Although there is no documentary record with Gluck's birthdate at the time of his birth, he himself gave it as 2 July 1714 on an official document requested by Paris that he signed in 1785 in Vienna in the presence of the French ambassador Emmanuel Marie Louis de Noailles. This has long been the commonly accepted date.[13] He was baptized Christophorus Willibaldus on 4 July 1714 in the village of Weidenwang,[14] a parish that at that time also included Erasbach.[2] Gluck himself never used the name Willibald. The church in Weidenwang was consecrated to Saint Willibald (as was the entire Eichstätt diocese to which it belonged), and the name Willibald is frequently found in the baptismal register, often as a second name. No documents contemporary with Gluck's life use the name Willibald. Only in the 19th century did scholars begin using it to distinguish the composer from his father's brother Johann Christoph, born in 1700, whose baptism had earlier been confused with that of the composer.[15]

In the year of Gluck's birth, the Treaty of Rastatt and the Treaty of Baden ended the War of Spanish Succession and brought Erasbach under Bavarian control.[16] Gluck's father had to reapply to retain his position and received no salary until after 1715, when he began receiving 20 gulden. He obtained additional employment in the vicinity of Weidenwang in 1715 as a forester in the service of Seligenporten Monastery, and after 1715, also with Plankstetten Abbey. In 1716 Alexander Gluck was cited for poor performance and warned he might be terminated.[17] He sold his house in August 1717 and voluntarily left Erasbach near the end of September to take up employment as head forester in Reichstadt, serving the Duchess of Tuscany,[18] the wealthy Anna Maria Franziska of Saxe-Lauenburg, since 1708 separated from her husband Gian Gastone de' Medici, the last duke of Tuscany.[19]

On 1 April 1722 Alexander Gluck took a position as forest-master under Count Philipp Joseph von Kinsky in Böhmisch Kamnitz, where Kinsky had increased his domains.[20] The family moved to the forester's house in nearby Oberkreibitz.[21]

In 1727 Alexander moved with his family to Eisenberg (Jezeří in Horní Jiřetín) to take his final post, head forester to Prince Philipp Hyazinth von Lobkowitz.[22] It is not sure if Christoph was sent to the Jesuit college in Chomutov, 20 km southwest.[23]

The Alsatian painter Johann Christian von Mannlich relates in his memoirs, published in 1810, that Gluck told him about his early life in 1774. He quotes Gluck as saying:

My father was forest master at N... in Bohemia and he planned that eventually I should succeed him. In my homeland everyone is musical; music is taught in the schools, and in the tiniest villages the peasants sing and play different instruments during High Mass in their churches. As I was passionate about the art, I made rapid progress. I played several instruments and the schoolmaster, singling me out from the other pupils, gave me lessons at his house when he was off duty. I no longer thought and dreamt of anything but music; the art of forestry was neglected.[24]

In 1727 or 1728, when Gluck was 13 or 14, he went to Prague.[25] A childhood flight from home to Vienna is included in several contemporary accounts of Gluck's life, including Mannlich's,[26] but some scholars have cast doubt on Gluck's picturesque tales of earning food and shelter by his singing as he travelled. Most now feel it is more likely that the object of Gluck's travels was not Vienna but Prague.[27] Gluck's German biographer Hans Joachim Moser claimed in 1940 to have found documents showing Gluck matriculated in logic and mathematics at the University of Prague in 1731.[28] Gerhard and Renate Croll find this astonishing,[29] and other biographers have been unable to find any documents supporting Moser's claim.[30] At the time the University of Prague boasted a flourishing musical scene that included performances of both Italian opera and oratorio.[2] Gluck sang and played violin and cello, and also the organ at Týn Church.[31]

Gluck eventually left Prague without taking a degree, and vanishes from the historical record until 1737.[2] Nevertheless, the memories of his family and indirect references to this period in later documents give good grounds for believing Gluck arrived in Vienna in 1734, where he likely was employed by the Lobkowitz family at their palace in the Minoritenplatz. Philipp Hyazinth Lobkowitz, Gluck's father's employer, died on 21 December 1734, and his successor, his brother Johann Georg Christian Lobkowicz, is thought to have been Gluck's employer in Vienna from 1735 to 1736. Two operas with texts Gluck himself was later to set were performed during this period: Antonio Caldara's La clemenza di Tito (1734) and Le cinesi (1735). It is likely that the Lobkowitz family introduced Gluck to the Milanese nobleman Prince Antonio Maria Melzi, who engaged Gluck to become a player in his orchestra in Milan. The 65-year-old prince married the 16-year-old Maria Renata, Countess of Harrach, on 3 January 1737, and not long after returned with Gluck to Milan.[32]

Question of Gluck's native language

According to the music historian Daniel Heartz, there has been considerable controversy concerning Gluck's native language. Gluck's protégé in Vienna, the Italian-born Antonio Salieri, wrote in his memoirs (translated into German by Ignaz von Mosel), that "Gluck, whose native tongue was Czech, expressed himself in German only with effort, and still more so in French and Italian."[33] Salieri also mentions that Gluck mixed several languages when speaking: German, Italian and French, like Salieri himself.[34] Gluck's first biographer, Anton Franz Schmid, wrote that Gluck grew up in a German-speaking area, and that Gluck learned to speak Czech, but did not need it in Prague and in his later life.[35] Heartz writes: "More devious manoeuvres have been attempted by Gluck's German biographers of this [the 20th] century, while the French ones have, without exception, taken Salieri at his word. His German biographer Max Arend objected that not a single letter written in Czech can be found, to which Jacques-Gabriel Prod'homme countered that "no letters written by Liszt in Hungarian were known either, but does this make him a German?"[36] Hans Joachim Moser wanted a lyric work in Czech as proof.[37] In fact, the music theorist Laurent Garcin, writing in 1770 (published 1772) before Gluck arrived in Paris, included Gluck in a list of several composers of Czech opéras-comiques (although such a work by Gluck has yet to be documented).[38] A presentation by Irene Brandenburg classifying Gluck as a Bohemian composer was considered controversial by her German colleagues.[39]

Italy

In 1737 Gluck arrived in Milan, and was introduced to Giovanni Battista Sammartini, who, according to Giuseppe Carpani, taught Gluck "practical knowledge of all the instruments".[40] Apparently, this relationship lasted for several years. Sammartini was not, primarily, a composer of opera, his main output being of sacred music and symphonies, but Milan boasted a vibrant opera scene, and Gluck soon formed an association with one of the city's up-and-coming opera houses, the Teatro Regio Ducale. There his first opera Artaserse was performed on 26 December 1741, dedicated to Otto Ferdinand von Abensberg und Traun. Set to a libretto by Metastasio, the opera opened the Milanese Carnival of 1742. According to one anecdote, the public would not accept Gluck's style until he inserted an aria in the lighter Milanese manner for contrast.

Nevertheless, Gluck composed an opera for each of the next four Carnivals at Milan, with renowned castrato Giovanni Carestini appearing in many of the performances, so the reaction to Artaserse was likely to have been reasonably favorable. He also wrote operas for other cities of Northern Italy in between Carnival seasons, including Turin and Venice, where his Ipermestra was given during November 1744 at the Teatro San Giovanni Crisostomo. Nearly all of his operas in this period were set to Metastasio's texts, despite the poet's dislike for his style of composition.

Travels: 1745–1752

In 1745 Gluck accepted an invitation from Lord Middlesex to become house composer at London's King's Theatre, probably travelling to England via Frankfurt and in the company of the violinist Ferdinand Philipp Joseph von Lobkowitz, the son of Phillip Hyacinth. The timing was unfortunate, as the Jacobite Rebellion had caused much panic in London, and for most of the year, the King's Theatre was closed. Six trio sonatas were the immediate fruits of his time. Gluck's two London operas (La caduta de' giganti and Artamene), eventually performed in 1746, borrowed much from his earlier works. Gluck performed works by Galuppi and Lampugnani, who both had worked in London. A more long-term benefit was exposure to the music of Handel – whom he later credited as a great influence on his style – and the naturalistic acting style of David Garrick, an English theatrical reformer. On 25 March, shortly after the production of Artamene, Handel and Gluck together gave a concert in the Haymarket Theatre consisting of works by Gluck and an organ concerto by Handel, played by the composer. On 14 April Gluck played on a glassharmonica in Hickford's Rooms, a concert hall in Brewer Street, Soho.[41] Handel's own experience of Gluck pleased that composer less: Charles Burney reports Handel as saying that "he [Gluck] knows no more of contrapunto, as my cook, Waltz".[41]

The years 1747 and 1748 brought Gluck two highly prestigious engagements. First came a commission to produce an opera for Pillnitz, performed by Pietro Mingotti's troupe, to celebrate a royal double wedding that would unite the ruling families of Bavaria and Saxony. Le nozze d'Ercole e d'Ebe, a festa teatrale, borrowed heavily from earlier works, and even from Gluck's teacher Sammartini. The success of this work brought Gluck to the attention of the Viennese court, and, ahead of such a figure as Johann Adolph Hasse, he was selected to set Metastasio's La Semiramide riconosciuta to celebrate Maria Theresa's birthday. Vittoria Tesi took the title role. On this occasion Gluck's music was completely original, but the displeasure of the court poet, Metastasio, who called the opera "archvandalian music", probably explains why Gluck did not remain long in Vienna despite the work's enormous popular success (it was performed 27 times to great acclaim). For the remainder of 1748 and 1749 Gluck travelled with Mingotti's troupe, contracting a venereal disease from the prima donna and composing the opera La contesa de' numi for the court at Copenhagen, where he repeated his concert on the glassharmonica.

In 1750 he abandoned Mingotti's group for another company established by a former member of the Mingotti troupe, Giovanni Battista Locatelli. The main effect of this was that Gluck returned to Prague on a more consistent basis. For the Prague Carnival of 1750 Gluck composed a new opera, Ezio (again set to one of Metastasio's works, with the manuscript located at the Lobkowicz Palace). His Ipermestra was also performed in the same year. The other major event of Gluck's stay in Prague was, on 15 September 1750, his marriage to Maria Anna Bergin, aged 18 years old, the daughter of a rich (but long-dead) Viennese merchant.[42] Gluck seems to have spent most of 1751 commuting between Prague and Vienna.

The year 1752 brought another major commission to Gluck, when he was asked to set Metastasio's La clemenza di Tito (the specific libretto was the composer's choice) for the name day celebrations of King Charles VII of Naples. The opera was performed on 4 November at the Teatro di San Carlo, and the world-famous castrato Caffarelli took the role of Sextus. For Caffarelli Gluck composed the famous, but notoriously difficult, aria "Se mai senti spirarti sul volto", which provoked admiration and vituperation in equally large measures. Gluck later reworked this aria for his Iphigénie en Tauride. According to one account, the Neapolitan composer Francesco Durante claimed that his fellow composers "should have been proud to have conceived and written [the aria]". Durante simultaneously declined to comment whether or not it was within the boundaries of the accepted compositional rules of the time.

Vienna

.jpg.webp)

Gluck finally settled in Vienna, where he became Kapellmeister invited by Prince Joseph of Saxe-Hildburghausen. He wrote Le cinesi for a festival in 1754 and La danza for the eighth birthday of the future Emperor Leopold II the following year. After his opera Antigono was performed in Rome in February 1756, Gluck was made a Knight of the Golden Spur by Pope Benedict XIV. From that time on, Gluck used the title "Ritter von Gluck" or "Chevalier de Gluck".

Gluck turned his back on Italian opera seria and began to write opéra comiques. In 1761 Gluck produced the groundbreaking ballet-pantomime Don Juan in collaboration with the choreographer Gasparo Angiolini; the more radical Jean-Georges Noverre was involved for the first time? The climax of Gluck's opéra comique writing was La rencontre imprévue (1764). By that time, Gluck created musical drama, based on Greek tragedy, with more compassion, influencing the latest style Sturm und Drang.

Under the teaching of Gluck, Marie Antoinette developed into a good musician. She learned to play the harp,[43] the harpsichord and the flute. She sang during the family's evening gatherings, as she had a beautiful voice.[44] All her brothers and sisters were involved in playing Gluck's music; on 24 January 1765 her brother Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor directed one of Gluck's compositions, Il Parnaso confuso.

In Spring 1774, she took under her patronage her former music teacher and introduced him to the Paris public. For that purpose, she asked him to compose a new opera, Iphigénie en Aulide. "Mindful of the Querelle des Bouffons between adherents of Italian and French opera, she asked the composer to set the libretto in French." To get to her goals she was assisted by the singers Rosalie Levasseur and Sophie Arnould. Gluck had gruff ways, demanding strict adherence from the cast when rehearsing. Gluck told the bass-bariton Henri Larrivée to change his ways. The soprano Arnould was replaced. He insisted that the chorus, too, had to act and become a part of the drama – that they could no longer just stand there posing stiffly and without expression while singing their lines. Gluck was assisted by François-Joseph Gossec, director of the Concert Spirituel. The Chevalier de Saint-Georges attended the first performance on 19 April; Jean-Jacques Rousseau was delighted with Gluck melodic style. Marie Antoinette received a large share of the credit.[45]

Operatic reforms

Gluck had long pondered the fundamental problem of form and content in opera. He thought both of the main Italian operatic genres, opera buffa and opera seria, had strayed too far from what opera should really be and seemed unnatural. Opera buffa had long lost its original freshness. Its jokes were threadbare and the repetition of the same characters made them seem no more than stereotypes. In opera seria, the singing was devoted to superficial effects and the content was uninteresting and fossilised. As in opera buffa, the singers were effectively absolute masters of the stage and the music, decorating the vocal lines so floridly that audiences could no longer recognise the original melody. Gluck wanted to return opera to its origins, focusing on human drama and passions and making words and music of equal importance.

Francesco Algarotti's Essay on the Opera (1755) proved to be an inspiration for Gluck's reforms. He advocated that opera seria had to return to basics and that all the various elements—music (both instrumental and vocal), ballet, and staging—must be subservient to the overriding drama. Several composers of the period, including Niccolò Jommelli and Tommaso Traetta, attempted to put these ideals into practice (and added more ballets).

In Vienna, Gluck met like-minded figures in the operatic world: Count Giacomo Durazzo, the head of the court theatre, and one of the primary instigators of operatic reform in Vienna ; the librettist Ranieri de' Calzabigi, who wanted to attack the dominance of Metastasian opera seria; the innovative choreographer Gasparo Angiolini; and the London-trained castrato Gaetano Guadagni.

The first result of the new thinking was Gluck's reformist ballet Don Juan, but a more important work was soon to follow. On 5 October 1762, Orfeo ed Euridice was given its first performance, on a libretto by Calzabigi, set to music by Gluck. Gluck tried to achieve a noble, Neo-Classical or "beautiful simplicity". The dances were arranged by Angiolini and the title role was taken by Guadagni, a catalytic force in Gluck's reform, renowned for his unorthodox acting and singing style. Orfeo, which has never left the standard repertory, showed the beginnings of Gluck's reforms. His idea was to make the drama of the work more important than the star singers who performed it, and to do away with dry recitative (recitativo secco, accompanied only by continuo) that broke up the action. In 1765, Melchior Grimm published "Poème lyrique", an influential article for the Encyclopédie on lyric and opera librettos.[46][47][48][49][50]

Gluck and Calzabigi followed Orfeo with Alceste (1767) and Paride ed Elena (1770), dedicated to his friend João Carlos de Bragança (Duke de Lafões), an expert on music and mythology, pushing their innovations even further. Calzabigi wrote a preface to Alceste, which Gluck signed, setting out the principles of their reforms:

- no da capo arias

- no opportunity for vocal improvisation or virtuosic displays of vocal agility or power

- no long melismas

- a more predominantly syllabic setting of the text to make the words more intelligible

- far less repetition of text within an aria

- a blurring of the distinction between recitative and aria, declamatory and lyrical passages, with altogether less recitative

- accompanied rather than secco recitative

- simpler, more flowing melodic lines

- an overture that is linked by theme or mood to the ensuing action

Joseph von Sonnenfels praised Gluck's tremendous imagination and the setting after attending a performance of Alceste.[51] In 1769 Gluck performed his operas in Parma.

On 2 September 1771 Charles Burney visited Gluck, living in Sankt Marx. Burney thought Gluck's preface, in which Gluck gives his “reasons for deviating from the beaten track”, important enough to give it almost in its entirety: "It was my intention to confine music to its true dramatic province, of assisting poetical expression, and of augmenting the interest of the fable; without interrupting the action, or chilling it with useless and superfluous ornaments; for the office of music, when joined to poetry, seemed to me, to resemble that of colouring in a correct and well disposed design, where the lights and shades only seem to animate the figures, without altering the out-line."[52] On 11 September Burney went to see Gluck to say goodbye; Gluck was still in bed, as he used to work in the night.

Paris

As his operas were not appreciated by Frederick II of Prussia, Gluck began to focus on France.[53] Under the patronage of Marie Antoinette, who had married the future French King Louis XVI in 1770, Gluck signed a contract for six stage works with the management of the Paris Opéra. He began with Iphigénie en Aulide. The premiere on 19 April 1774 sparked a huge controversy, almost a war, such as had not been seen in the city since the Querelle des Bouffons. Gluck's opponents brought the leading Italian composer Niccolò Piccinni to Paris to demonstrate the superiority of Neapolitan opera, and the "whole town" engaged in an argument between "Gluckists" and "Piccinnists". The composers themselves took no part in the polemics, but when Piccinni was asked to set the libretto to Roland, on which Gluck was also known to be working, Gluck destroyed everything he had written for that opera up to that point.

On 2 August 1774 the French version of Orfeo ed Euridice was performed, more Rameau-like,[54] with the title role transposed from the castrato to the tenor voice. This time Gluck's work was better received by the Parisian public. In the same year, Gluck returned to Vienna, where he was appointed composer to the imperial court (18 October 1774) after 20 years serving as Kapellmeister. Over the next few years, the now internationally famous composer would travel back and forth between Paris and Vienna. He became friends with the poet Klopstock in Karlsruhe. On 23 April 1776, the French version of Alceste was given.

During the rehearsals for Echo et Narcisse in September 1779, Gluck became dangerously ill.[55] Since the opera itself was a failure, running for only 12 performances, Gluck decided to return to Vienna within two weeks. In that city Die unvermuthete Zusammenkunft or Die Pilgrime von Mekka (1772), a German version of La rencontre imprévue, had been performed 51 times.[56]

His musical heir in Paris was the composer Antonio Salieri, who had been Gluck's protégé since he arrived in Vienna in 1767, and later had made friends with Gluck. Gluck brought Salieri to Paris with him and bequeathed him the libretto for Les Danaïdes by François-Louis Gand Le Bland Du Roullet and baron de Tschudi. The opera was announced as a collaboration between the two composers; however, after the overwhelming success of its premiere on 26 April 1784, Gluck revealed to the prestigious Journal de Paris that the work was wholly Salieri's.

Last years

In Vienna Gluck wrote a few more minor works, spending the summer with his wife in Perchtoldsdorf, famous for its wine (Heuriger). Gluck suffered from melancholy and high blood pressure.[55] In 1781, he brought out a German version of Iphigénie en Tauride. Gluck dominated the season's proceedings with 32 performances.[57] On 23 March 1783 he seems to have attended a concert by Mozart who played KV 455, variations on La Rencontre imprévue by Gluck (Wq. 32).[58]

On 15 November 1787, lunching with friends, Gluck suffered a heart arrhythmia and died a few hours later, at the age of 73. Usually, it is mentioned Gluck had several strokes and became paralyzed on his right side. Robl, a family doctor, had doubts as Gluck was still able to play his clavicord or piano in 1783.[59] At a formal commemoration on 8 April 1788, his friend, pupil and successor Salieri conducted Gluck's De profundis, and a requiem by the Italian composer Niccolò Jommelli was given. His death opened the way for Mozart at court, according to H. C. Robbins Landon. Gluck was buried in the Matzleinsdorfer Friedhof. On 29 September 1890,[60] his remains were transferred to the Zentralfriedhof; a tomb was erected containing the original plaque.[61][62]

Legacy

Although only half of his work survived after a fire in 1809,[63] Gluck's musical legacy includes approximately 35 complete full-length operas plus around a dozen shorter operas and operatic introductions, as well as numerous ballets and instrumental works. His reforms influenced Mozart, particularly his opera Idomeneo (1781).[54] He left behind a flourishing school of disciples in Paris, who would dominate the French stage throughout the Revolutionary and Napoleonic period. As well as Salieri, they included Sacchini, Cherubini, Méhul and Spontini. His greatest French admirer would be Hector Berlioz, whose epic Les Troyens may be seen as the culmination of the Gluckian tradition. Though Gluck wrote no operas in German, his example influenced the German school of opera, particularly Carl Maria von Weber and Richard Wagner, whose concept of music drama was not so far removed from Gluck's own.

Works

| External audio | |

|---|---|

Here on Archive.org |

Notes

- ↑ Brown & Rushton 2001, Introduction and "1. Ancestry, early life and training."; Heartz 1988, pp. 517–526. Sources differ concerning Gluck's nationality: Kuhn 2000, p. 272, and Croll 1991, p. 308, said he was German, while Brown & Rushton 2001 and Howard 2003 (p. xi) gave Bohemian; Hayes et al. 1992, p. 453, Bohemian-Austrian; and Harewood & Peattie 1997, p. 261, Austrian; G. Banat, p. 144 recognized him as Bavarian.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Brown & Rushton 2001, "1. Ancestry, early life and training."

- 1 2 3 Croll & Croll 2014, p. 13.

- ↑ Heartz 1988, p. 517; Croll & Croll 2014, p. 13.

- ↑ Prod'homme 1948 (1985), p. 17;Heartz 1988, p. 518; Brown & Rushton 2001; Croll2 & Croll 2014, p. 13.

- ↑ Prod'homme 1948 (1985), p. 17; Brown & Rushton 2001.

- ↑ Brown & Rushton 2001; Heartz 1988, p. 518.

- ↑ Schmid 1854, p. 11; Prod'hommme 1948 (1985), p. 18; Heartz 1988, p. 518; Brown & Rushton 2001.

- 1 2 Robl 2015.

- ↑ Croll & Croll 2014, p. 14.

- ↑ Croll & Croll 2014, p. 15. The record of ownership from the time it was built to the present is unbroken, and, although the house has been remodeled and modernized, it is believed to retain much of its original appearance. There is a plaque on the side of the house which reads: "Hier wurde am 2.7.1714 der Komponist Christoph Willibald Gluck geboren" ("Here was born on 7/2/1714 the composer Christoph Willibald Gluck"); see a picture of the plaque at Commons.

- ↑ Croll & Croll 2014, p. 15. In the cited document he is named as "Jäger Alexander Gluck zu Erasbach". According to Croll & Croll, a different house, located in Weidenwang, also designated by many as Gluck's birthplace is well documented and was built about ten years after his birth.

- ↑ Croll & Croll 2010, p. 12. Other sources giving this date include Einstein 1936, p. 3; Brown & Rushton 2001. The authenticity of the 1785 document has been disputed by Robl 2015, pp. 141–147.

- ↑ Croll & Croll 2014, p. 12.

- ↑ See also Schmid 1854, p. 11.

- ↑ Croll & Croll 2014, p. 16; Heartz 1988, p. 518.

- ↑ Croll & Croll 2014, p. 16.

- ↑ Croll & Croll 2014, p. 17.

- ↑ During the Lauenburg war of succession (1690–1693) the Habsburg emperor banned Anna Maria Franziska of Saxe-Lauenburg and her sister to Reichstadt and forced them to marry one of his generals in order to pay his debts to them. Franziska refused to marry Eugene of Savoy, accepted the next candidate Gian Gastone, who came to the conclusion Reichstadt was a boring place to live. She refused to follow him to Florence, being more interested in horses and hunting than in him.

- ↑ Prod'homme 1948 (1985), p. 20; Howard 1995, p. 1; Croll & Croll 2014, p. 18.

- ↑ Croll & Croll 2014, p. 18; Brown & Rushton 2001.

- ↑ Howard 1995, p. 1.

- ↑ Daniel Heartz relates that this assertion has been the subject of much debate. Gluck himself does not appear in the list of students, although one of his younger brothers does. All instruction was in Latin, and Gluck's failure to learn Latin, which he had to study later in life, argues against it (Heartz 1988, p. 520).

- ↑ Quoted and translated by Heartz 1988, p. 521, who cites and provides the French original: "Gluck à Paris en 1774", La Revue musicale (1934), p. 260: "Mon père, nous disoit-il, étoit maître des eaux et forêts à N... en Bohème; il m'avoit destiné à le remplacer un jour dans son poste. Dans mon pays tout le monde est musicien; on enseigne la musique dans les écoles et dans les moindres villages les paysans chantent et jouent des différens instrumens pendant la grand-messe dans leurs églises. Comme j'étois passionné pour cet art, je fis des progrès rapides. Je jouois de plusieurs instrumens, et le maître, en me distinguant des autres écoliers, me donna des leçons chez lui dans ses moments de loisir.

- ↑ Heartz 1988, p. 521.

- ↑ Howard 1995, pp. 2–3, provides commentary and an English translation of the entire excerpt from Mannlich.

- ↑ Heartz 1988, p. 522; Brown & Rushton, 2001; Croll & Croll 2014, p. 24.

- ↑ Moser 1940, p. 24.

- ↑ Croll & Croll 2014, p. 25.

- ↑ Howard 1995, p. 6; Heartz 1988, p. 522, citing Arnošt Mahler "Glucks Schulzeit. Zweifel und Widerspruche in den biographischen Daten," Die Musikforschung, vol. 27 (1974), pp. 457–460.

- ↑ Howard 1995, p. 6.

- ↑ Howard 1995, pp. 8–9; Croll & Croll 2014, p. 27.

- ↑ Quoted and translated by Heartz 1988, pp. 524–525, citing Mosel 1827, p. 93: "Gluck, dessen Muttersprache die böhmisch war, drückte sich in der deutschen, und noch mehr in der französischen und italienischen, nur mit Mühe aus... ."

- ↑ Mosel 1827, p. 93.

- ↑ Schmid 1854, pp. 389–390; cited by Heartz 1988, p. 525.

- ↑ Heartz 1988, p. 525; Arend 1920, p. 20; Prod'homme 1948, chapter 1.

- ↑ Moser 1940, pp. 20–21, cited by Heartz 1988, p. 525.

- ↑ Garcin 1772, p. 115; reproduced by Heartz 1988, p. 527; cited by Brown & Rushton 2001.

- ↑ Mitteilungen der Internationalen Gluck-Gesellschaft Nr. 2, July 1997 (in German)

- ↑ Brown & Rushton 2001.

- 1 2 William Zeitler (2009), "The Glass Armonica, Benjamin Franklin's Magical Musical Invention: C.W. Gluck", at glassarmonica.com. Retrieved 8 June 2019 .

- ↑ Wien Geschichte Wiki on Gluck.

- ↑ Cronin 1989, p. 45.

- ↑ Cronin 1989, p. 46.

- ↑ Banat, Gabriel (2006). The Chevalier de Saint-Georges : virtuoso of the sword and the bow. Hillsdale, N.Y.: Pendragon Press. ISBN 1-57647-109-8., p. 146-150.

- ↑ Encyclopédie Larousse en ligne – Melchior baron de Grimm, Éditions Larousse, http://www.larousse.fr.

- ↑ Thomas, 1995, p. 148

- ↑ Heyer (ed.) 2009, p. 248

- ↑ Lippman 2009, p. 171

- ↑ "Position Papers: Seminar 1. Music: universal, national, nationalistic" Archived 18 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine Faculty of Arts and Humanities, King's College London

- ↑ Historische Drucke mit URN (Verbundkatalog mit Lokalbestand) / Briefe über die wienerische... [36], sammlungen.ulb.uni-muenster.de.

- ↑ Charles Burney on Gluck's Reform of Opera Seria (1773)

- ↑ Mueller von Asow 1962.

- 1 2 Opera – From the “reform” to grand opera. Encyclopædia Britannica online.

- 1 2 Robl 2013, p. 48.

- ↑ The Mozart Compendium, p. ?

- ↑ Otto Mitchner (1970) Das alte Burgtheater als Opernbühne, p. 99

- ↑ H. C. Robbins Landon (1990) The Mozart Compendium

- ↑ Robl 2013, pp. 50–54

- ↑ ANNO, Neue Freie Presse, 1890-09-29, p. 2, http://www.anno.onb.ac.at.

- ↑ Brown & Rushton 2001, "7. Final years in Vienna.".

- ↑ "Gluck, Christoph Willibald Ritter von", at Wikisource from Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, 1879 (in German).

- ↑ Daniela Philippi (2012), "Zur Überlieferung der Werke Christoph Willibald Glucks in Böhmen, Mähren und Sachsen", p. 75.

Sources

- Arend, Max (1920). Gluck, eine Biographie. Berlin: Schuster & Loeffler. Copy at HathiTrust.

- Brown, Bruce Alan (1991). Gluck and the French Theatre in Vienna. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-316415-4.

- Brown, Bruce Alan; Rushton, Julian (2001). "Gluck, Christoph Willibald, Ritter von", Grove Music Online, edited by L. Macy (accessed 11 November 2007), grovemusic.com (subscription access).

- Croll, Gerhard (1991). "Gluck, Christoph", vol. 5, pp. 308–10, in The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th edition. Chicago. ISBN 978-0-85229-553-3.

- Croll, Gerhard; Croll, Renate (2010). Gluck. Sein Leben, seine Musik (in German). Kassel; New York: Bärenreiter. ISBN 978-3-7618-2166-4.

- Croll, Gerhard; Croll, Renate (2014). Gluck. Sein Leben, seine Musik (2nd edition, in German). Kassel; New York: Bärenreiter. ISBN 978-3-7618-2378-1.

- Cronin, Vincent (1989). Louis and Antoinette. Collins Harvill ISBN 978-0-00-272021-2.

- Einstein, Alfred (1936). Gluck, English translation by Eric Blom, 1964. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-019530-1 (1972 paperback edition).

- Garcin, Laurent (1772). Traité du mélo-drame. Paris: Chez Vallat-la-Chapelle. OCLC 764008429. Copy at Gallica.

- Harewood, The Earl of; Peattie, Antony, editors (1997). The New Kobbé's Opera Book. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. London: Ebury Press. ISBN 0-09-181410-3.

- Hayes, Jeremy; Brown, Bruce Alan; Loppert, Max; Dean, Winton (1992). "Gluck, Christoph Willibald", vol. 2, pp. 453–64, in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, edited by Stanley Sadie. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-56159-228-9.

- Heartz, Daniel (1988). "Coming of Age in Bohemia: The Musical Apprenticeships of Benda and Gluck", The Journal of Musicology, vol. 6, no. 4 (Autumn, 1988), pp. 510–27. JSTOR 763744. Also available here.

- Howard, Patricia (1995). Gluck: An Eighteenth-Century Portrait in Letters and Documents. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816385-5.

- Howard, Patricia (2003). Christoph Willibald Gluck. A Guide to Research, Second Edition. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-94072-6

- Kuhn, Laura (2000). Baker's Dictionary of Opera. New York: Schirmer. ISBN 978-0-02-865349-5.

- Mosel, Ignaz Franz von (1827). Ueber das Leben und die Werke des Anton Salieri, K.k. Hofkapellmeister. Vienna: Wallishausser. Copy at Bavarian State Library website.

- Moser, Hans Joachim (1940). Christoph Willibald Gluck : die Leistung, der Mann, das Vermächtnis. Stuttgart: Cotta. OCLC 10663283.

- Mueller von Asov, Hedwig and E. H., editors (1963). Collected correspondence and papers of Christoph Willibald Gluck, translated by Stewart Thomson (copy at Internet Archive). New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Prod'homme, Jacques-Gabriel (1948; revised 1985). Gluck. Paris: Société de'Éditions Françaises et Internationales. OCLC 5652892, 692250253. 1985 revision by Marie Fauquet: Paris: Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-01575-0.

- Robl, Werner (2013). Christoph Willibald Gluck wurde doch in Weidenwang geboren (in German).

- Robl, Werner (2015). Auf den Spuren der Familie Gluck in den Dörfern Weidenwang und Erasbach Fallstricke und Lösungen der regionalen Gluck-Forschung. Berching.

- Schmid, Anton Franz (1854). Christoph Willibald Ritter von Gluck. Dessen Leben und tonkünstlerishes Wirken. Leipzig: Friedrich Fleischer. Copy at Google Books.

Further reading

- Abert, A. A., Christoph Willibald Gluck (in German) (Munich, 1959) OCLC 5996991

- Felix, W., Christoph Willibald Gluck (in German) (Leipzig, 1965) OCLC 16770241

- Heartz, D., "From Garrick to Gluck: the Reform of Theatre and Opera in the Mid-Eighteenth Century", Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, xciv (1967–68), pp. 111–27. ISSN 0080-4452.

- Gibbons, W. Building the Operatic Museum: Eighteenth-Century Opera in Fin-de-siècle Paris. University of Rochester Press, 2013. ISSN 1071-9989

- Howard, P., Gluck and the Birth of Modern Opera. London, 1963 OCLC 699685

- Howard, P., "Orfeo and Orphée", The Musical Times, cviii (1967), pp. 892–94. ISSN 0027-4666

- Howard, P., "Gluck"s Two Alcestes: a Comparison", The Musical Times, cxv (1974), pp. 642–93. ISSN 0027-4666

- Howard, P., "Armide: a Forgotten Masterpiece", Opera, xxx (1982), 572–76. ISSN 0030-3526

- Kerman, Joseph, Opera as Drama. New York, 1956, 2/1989. Revised 1989 edition ISBN 978-0-520-06274-0.

- Noiray, M., Gluck's Methods of Composition in his French Operas "Iphigénie en Aulide", "Orphée", "Iphigénie en Tauride". Dissertation, University of Oxford, 1979

- Rushton, J., "Iphigénie en Tauride: the Operas of Gluck and Piccinni", Music & Letters, liii (1972), pp. 411–30. ISSN 0027-4224

- Rushton, J., "The Musician Gluck", The Musical Times, cxxvi (1987), pp. 615–18. ISSN 0027-4666

- Rushton, J., "'Royal Agamemnon': The Two Versions of Gluck's Iphigénie en Aulide", Music and the French Revolution, ed. M. Boyd (Cambridge, 1992), pp. 15–36. ISBN 978-0-521-08187-0.

- Saloman, O. F., Aspects of Gluckian Operatic Thought and Practice in France (diss., Columbia University, 1970)

- Sternfeld, F. W., "Expression and Revision in Gluck's Orfeo and Alceste, Essays Presented to Egon Wellesz" (Oxford, 1966), pp. 114–29

- Youell, Amber Lynne (2012) "Opera at the Crossroads of Tradition and Reform in Gluck's Vienna", PhD dissertation, Columbia University

External links

- Free scores by Christoph Willibald Gluck in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free scores by Christoph Willibald Gluck at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Digital catalogue raisoné

- Gluck the Reformer. William Christie & John Eliot Gardiner feature in this documentary on the operas of Christoph Willibald Gluck