| Church of St Giles | |

|---|---|

St. Giles, Stoke Poges | |

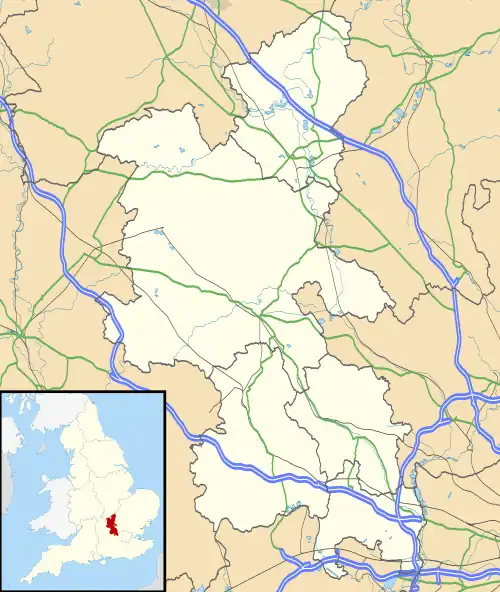

Church of St Giles Location in Buckinghamshire | |

| 51°32′06″N 0°35′42″W / 51.535°N 0.595°W | |

| Location | Stoke Poges, Buckinghamshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Website | |

| History | |

| Dedication | Saint Giles |

| Associated people | Rev. Natasha Brady |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Church of England parish church |

| Heritage designation | Grade I |

| Designated | 23 September 1955 |

| Architectural type | Church |

St Giles' Church is an active parish church in the village of Stoke Poges, Buckinghamshire, England. A Grade I listed building, it stands in the grounds of Stoke Park, a late-Georgian mansion built by John Penn. It is famous as the apparent inspiration for Thomas Gray's poem Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard; Gray is buried in the churchyard.

History and architecture

The origins of the church are Anglo-Saxon and Norman.[1] The tower dates from the 13th century.[2] The adjacent Hastings chapel was constructed in 1558 by Edward Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings of Loughborough, owner of the manor of Stoke Poges, who also undertook a substantial enlargement of the neighbouring manor house.[3][4]

St Giles comprises a "battlemented" tower,[5] a nave, a chancel and the Hastings Chapel.[3] The church is built mainly of flint and chalk stone, with tiled roofs.[6] The exception is the Hastings Chapel which is constructed of red brick.[3] The style of the chapel is later than the Gothic of the church; Simon Jenkins, the writer and former chairman of the National Trust, describes it as "Tudor".[5] The church has extensions to either side, a vestry of the early 20th century, and an entrance and vestibule installed in the Victorian period to provide private access to the church for the owners of the adjacent manor house. Elizabeth Williamson, in the 2003 revised edition, Buckinghamshire, of the Pevsner Buildings of England series, considered the Victorian porch an "excrescence".

During the Victorian era, a restoration was carried out by George Edmund Street.[7] Jenkins, in his volume England's Thousand Best Churches, thought that the exterior was treated more sympathetically than the interior. Of the latter, he describes the removal of the plasterwork in the nave, together with the replacement of the Norman chancel arch and the opening up of the hammerbeam roof, as giving the church the appearance of "a barn".[5]

St Giles remains an active parish church in the Church of England, administered as part of the Diocese of Oxford.[8][9] The churchyard has been used as a filming location. In the opening sequence of the James Bond movie, For Your Eyes Only, Bond enters the churchyard through the lychgate to pay his respects at the grave of his wife, Teresa.[10] The churchyard also features in Judy Garland's final film, I Could Go On Singing.[11][12]

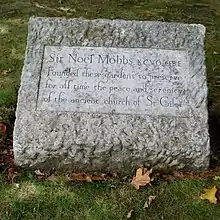

Adjacent to the church are the Stoke Poges Memorial Gardens, founded in 1935 by Sir Noel Mobbs to ensure "the maintenance in perpetuity of the peace, quietness and beauty of the ancient church and churchyard".[13][14] The gardens were landscaped by Edward White[15] and contain a number of private plots for the interment of ashes, within a larger, Grade I listed park.[16][17][18] The ashes of the film director Alexander Korda and the broadcaster Kenneth Horne, among others, are interred in the garden.[17]

St Giles is a Grade I listed building.[19] Gray's tomb is designated Grade II.[20] The Gray Monument (adjacent to St Giles' church and owned by the National Trust)[21] is listed at Grade II*.[22] The lychgate is by John Oldrid Scott and is a Grade II listed structure.[23] The churchyard also contains war graves of six British armed services personnel, four of World War I and two of World War II.[24]

Thomas Gray and Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard

Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree's shade,

Where heaves the turf in many a mouldering heap,

Each in his narrow cell for ever laid,

The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep.

Gray's Elegy (1750)[25]

Thomas Gray was a regular visitor to Stoke Poges, which was home to his mother and an aunt,[26] and the churchyard at St Giles is reputed to have been the inspiration for his Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, though this is not universally accepted.[27] Some scholars suggest that much, or all, of the poem was written in Cambridge, where Gray lived.[28][29] Other commentators have identified as alternative possibilities St Mary's, Everdon, Northamptonshire; and St Laurence's Church, Upton-cum-Chalvey, Berkshire.[30] The poem certainly had a long gestation,[31] but it was completed at Stoke Poges in 1750. In June of that year, Gray wrote to his friend and supporter, Horace Walpole; "I have been here at Stoke a few days and having put an end to a thing, whose beginning you have seen long ago, I immediately send it to you."[32] A. L. Lytton Sells writes that there is "no doubt" about the identification of St. Giles as the churchyard of Gray's Elegy,[33] and Robert L. Mack calls it "very close to irrefutable".[25]

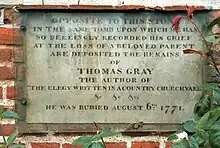

In 1771 Gray was buried (in accordance with his instructions) in the churchyard, in the vault erected for his mother and aunt.[26] The tomb above records the names, ages and dates of death of Gray's mother and aunt, and his own tribute to his mother ("the careful tender mother of many children, one of whom alone had the misfortune to survive her")[34] but no reference to Gray himself. Instead, his death and burial are recorded on a plaque set into the adjacent, external wall of the Hastings Chapel.

Gray's Monument, a sarcophagus set on a pedestal inscribed with stanzas from the Elegy,[22] was commissioned by John Penn as a memorial to Gray himself, as a tribute to the Elegy, and as an eye-catcher for Penn’s Stoke Park estate.[21]

Gallery

Gray's tomb, to the left

Gray's tomb, to the left Plaque set into the wall of the Hastings Chapel opposite Gray's tomb

Plaque set into the wall of the Hastings Chapel opposite Gray's tomb Gray's Monument

Gray's Monument Watercolour of St Giles by John Constable, (1834)

Watercolour of St Giles by John Constable, (1834) Memorial to Noel Mobbs in the Stoke Poges Memorial Gardens

Memorial to Noel Mobbs in the Stoke Poges Memorial Gardens

References

- ↑ "Restoration of St Giles' Church". Stoke Poges Parish Council. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ "Stoke Poges St Giles". National Churches Trust. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- 1 2 3 Pevsner & Williamson 2003, p. 651.

- ↑ "Edward Hastings (1519-1572)". History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- 1 2 3 Jenkins 1999, p. 37.

- ↑ Page, William (1925). "A History of the County of Buckingham". Victoria County History. British History Online. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ Pevsner & Williamson 2003, p. 652.

- ↑ "Stoke Poges St Giles". Church of England. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ "Stoke Poges: St Giles". Church of England Heritage Database. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ "Picturesque Lych Gate with links to James Bond and famous Thomas Gray poem listed". Historic England. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ "I Could Go on Singing (1963)". Reelstreets. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ Houston, Penelope. "I Could Go On Singing". BFI (via Sight and Sound). Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ↑ "Unforgettable Gardens – Stoke Poges Memorial Gardens". Buckinghamshire Gardens Trust. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ "Sir Noel Mobbs". Mobbs Memorial Trust. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ↑ "Gardens of Remembrance, Stoke Poges - Slough". Parks & Gardens UK. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Stoke Poges Gardens of Remembrance (Grade I) (1001255)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- 1 2 "Stoke Poges Memorial Garden". Buckinghamshire Culture. 25 August 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ "Stoke Poges Memorial Gardens" (PDF). Buckinghamshire County Council. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Church of St Giles, Stoke Poges (Grade I) (1164966)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Tomb of Thomas Gray, his mother Dorothy Gray and his aunt Mary Antrobus in churchyard of St Giles Church, Stoke Poges (Grade II) (1124345)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- 1 2 "Gray's Monument and Gray's Field Stoke Poges, Buckinghamshire". National Trust. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- 1 2 Historic England. "Gray's Monument, Stoke Poges (Grade II*) (1124346)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Lych gate and attached stone and flint wall, Church of St Giles, Stoke Poges (Grade II) (1475583)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ "Stoke Poges (St Giles) Churchyard". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- 1 2 Mack 2000, p. 12.

- 1 2 Lambton, Lucinda. "My elegy for a country church memorial". The Oldie. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ Watkins, Jack (23 September 2022). "In Focus: The enduring beauty of Thomas Gray's Elegy Written In A Country Churchyard". Country Life. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ Rumens, Carol (17 January 2011). "Poem of the week". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ↑ Minns, Walker (2 March 2022). "Tombstone views - Picturing Gray's Elegy". Apollo Magazine. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ↑ Page, William (1925). "A History of the County of Buckingham". Victoria County History. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ↑ Miller, John J. (17 May 2013). "Meditation on Mortality". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ↑ Mack 2000, p. 390.

- ↑ Sells & Sells 1980, p. 176.

- ↑ Mack 2000, p. 7.

Sources

- Jenkins, Simon (1999). England's Thousand Best Churches. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-713-99281-6. OCLC 42004142.

- Mack, Robert (2000). Thomas Gray: A Life. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08499-3.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Williamson, Elizabeth (2003). Buckinghamshire. The Buildings of England. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09584-5.

- Sells, A. Lytton; Sells, Iris Esther Robertson (1980). Thomas Gray, His Life and Works. London: G. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-049-28043-4.