College Hill | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Arch visible in background with Bissell Water Tower, October 2013 | |

Location (red) of College Hill within St. Louis | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Missouri |

| City | St. Louis |

| Wards | 21, 3 |

| Government | |

| • Aldermen |

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.39 sq mi (1.0 km2) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

| • Total | 1,243 |

| • Density | 3,200/sq mi (1,200/km2) |

| ZIP code(s) | Part of 63107 |

| Area code(s) | 314 |

| Website | stlouis-mo.gov |

College Hill is a neighborhood of the City of St. Louis, Missouri. The name College Hill was given to this area because it was the location of the Saint Louis University College Farm. This area, bounded generally by Warne Ave., O'Fallon Park, I-70, Grand Boulevard, and W. Florissant Ave., was acquired by the University for garden and recreation purposes in 1836. It was subdivided in the early 1870s.

The Bissell Mansion, the Old Water Tower at 20th Street and East Grand Avenue, and the Red Water Tower at Bissell Street and Blair Avenue are mainstays in this old Northside neighborhood and are testimony of a rich historical heritage. The housing of this neighborhood dates back between 1880 and 1920. Townhouses and four family flats predominate the neighborhood, with a mixture of single-family brick dwellings. The houses have large yards and are ideal for landscaping. The homes located near the crest of the hillside bluff enjoy a view of the river and its valleys. Nearly half of the housing dwellings are owner-occupied. Historically the area's commercial center has been concentrated along East Grand around the Old Water Tower with a strip along W. Florissant Avenue.

History

College Hill Farm

Much of what is presently identified as College Hill grew out of a 300-acre farmstead purchased by Saint Louis University in 1836. At that time, the university was engaged in transferring the location of its seminary from Florissant to the City of St. Louis. Although the university constructed a building for such purposes on Washington Avenue by the early 1830s, residential development in and around the area prompted trustees to search for a more suitable location, which would provide ample space for growth. What soon became known as College Hill Farm (in relation to the university’s ownership) was partially developed when plans were laid out in 1836. During the initial phases of construction, the project’s contractor died, and plans were placed on hold. Though Saint Louis University intended to continue the College Hill campus project, this was abandoned when in 1843, plans turned toward developing a central downtown campus. A second attempt by the university to use the College Hill property arose in 1858, when at least one building was constructed to support a theological school. The effort was abandoned two years later when the theology program transferred to Boston. In 1867, the university purchased what became its current campus, a parcel measuring 400 feet on Grand Avenue by 360 feet on Lindell Avenue for a cost of $52,600. The acquisition was funded through the subdivision and sale of the university’s College Hill property.[2]

Lowell

Prior to its associations with Saint Louis University, for which College Hill was named, a portion of the neighborhood was the Town of Lowell, platted in 1849 by E.C. Hutchinson, Josephine Hall, Edward F. Pittman, Robert Hall, and Wm. Garnett. Lowell consisted of a 40-block area between the Mississippi River and Bellefontaine Road, from Grand Avenue to Adelaide, formerly O’Fallon Avenue. The university’s holdings (College Hill Farm) adjoined Lowell at the west, extending south from O’Fallon Park between the Bellefontaine Road and Penrose, formerly Belle Street, and E. Prairie, formerly Bryan, and Adelaide, formerly O’Fallon Avenue.[3]

In 1876, the City of St. Louis expanded its boundaries, incorporating Lowell, by which time the university farmstead had been subdivided and sold for development. By the early 1880s, all but a single parcel bounded by Bellefontaine Road (east), E. Linton Avenue (north), Blair Street (west; formerly Henry Street) and DeSoto Avenue (south) had been subdivided into small lots. The larger undivided parcel remained under the ownership of Saint Louis University and supported a single building (likely constructed for the theological school).[4][5]

The street grid for Lowell follows the Mississippi River, and is at a slightly different angle than the grid in Hyde Park. The Lowell grid extends into the O'Fallon Park and Walnut Part East neighborhoods, but eventually intersects with the St. Charles Rock Road grid. Streets on the Lowell grid include College Avenue and Obear Street.

Architecture

O'Fallon Park

The largest land owner in the area was Colonel John O'Fallon, whose holdings of over 600 acres (2.4 km2) embraced the present O'Fallon Park. This was the site of the mansion. It was said that during excavations for its foundations during the 1850s that Indian and mound builder's artifacts were discovered. The house was quite large and contained more than fifty rooms in its four stories. Colonel O'Fallon was born in Kentucky in 1791 and came to St. Louis as a young man to work as an Indian agent under his uncle, General William Clark.

After making a fortune in the Indian trade, O'Fallon purchased the large tract on Bellfontaine Road. He chose the highest point on the property for the location of his mansion which he named "Athlone" after his father's Irish birthplace. Keeping the present park sit as his estate, O'Fallon sold off the remainder at a large profit. He augmented his fortune in railroading and banking and later donated one million dollars to local schools and colleges. Following Colonel O'Fallon's death in 1865, the estate was sold to the city for a park in 1875 for $260,000. The mansion was partially burned in the same year and was razed in 1893.

O'Fallon Park became popular as a driving park and picnic grounds in the late decades of the nineteenth century. During the 1890s the lake was constructed and an observatory for sight seeing was erected. An island was placed in the lake in 1904 and retaining walls were erected around it to hold its earthen banks. Boating was introduced on the lake following the erection of the boat house in 1908. Electric lighting came to the park in 1914 and some plaster statuary was placed there after the World's Fair. The statues have long since disappeared.

The park originally covered 150 acres (0.61 km2) and was expanded in 1917 when the Catholic Archdiocese donated an adjacent area of eight and a half acres. This was a former cemetery which became a bird sanctuary after its acquisition by the City. The park's area was reduced by five and a half acres in 1954 when the State Highway Department acquired the right of way for the Mark Twain Expressway.[6]

Bissell Point Water Works

The vicinity of East Grand Avenue is tied to the development of the City Water Works system. The need for a new waterworks became apparent in 1863, when the City's existing facility had become incapable of furnishing a plentiful water supply. In that year the state passed an act for the new waterworks, creating a Board of Commissioners to administer it and authorizing insurance of $3,000,000 in bonds for construction.

In 1865, the Board appointed James P. Kirkwood as Chief Engineer. Mr. Kirkwood devised a plan to locate a low service pumping station, settling basins, filter beds at Chain of Rocks, with a high service station at Baden and reservoirs at Compton Hill and near Wellston. This plan was rejected in 1866 in favor of a plant at Bissell Point, with basins but no filtering works. The site at Bissell Point was originally a portion of the Lewis and Bissell estate. In 1867, Kirkwood was succeeded as engineer by Thomas J. Whitman, who supervised construction of the Bissell Point plant (Whitman was a brother of the poet Walt Whitman).

Upon completion in 1869 the Bissell Point high service pumping station consisted of handsome, one and two story buildings of brick with cut stone trim. On a pediment above the main entrance were two sculptured figures symbolizing the "Union of the Waters" of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. The plan included an engine room and boiler house with an ornamental smokestack 134 feet (41 m) high. Large settling basins were located on the site.[6]

Water Towers

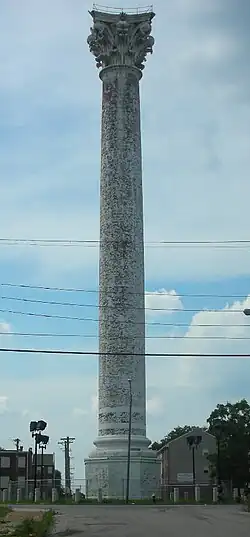

Two standpipe water towers which were connected to the Bissell Point plant are on the National Register of Historic Places. The Grand Avenue Water Tower, built in 1871, and the Bissell Tower, built in 1887.

The Bissell Point plant included a standpipe, which is the present Grand Avenue Water Tower at 20th Street and East Grand Avenue, and the reservoir at Compton Hill. Designed by George I. Barnett, the first architect to receive training abroad,[7] the tower on East Grand was placed in service in 1871, and was considered to be the largest perfect Corinthian column in existence, reaching a height of 154 feet (47 m). In the late 1920s lights were placed on top of the Corinthian tower to serve as aviation beacons. They were extinguished in World War II as a security precaution and were reactivated in 1949 to guide flyers to Lambert Field. The lights are presently not in use and the tower itself has not been used for its original purpose for many years.

Another water tower landmark in the area is the Red Water Tower or Bissell Tower. The 206-foot (63 m) high tower was built in 1887 at a cost of $79,789, and designed by architect William S. Eames, who was then the assistant city water commissioner. Sometimes called the "New Red" tower, it was erected as a stand pipe to augment the "Old Water Tower" on Grand, and help counter the water surge from the new high service pumps at Bissell Point. Named for its red brick construction, it was described in the 1980 RCGA commerce magazine, "Also visible from Interstate 70 is the minaret-like Bissell Water Tower, built in 1887 at the intersection of Bissell and Blair sts. in the center of a populous northside residential area. At the top of the square tower, brick is corbelled out to support a round observation deck with a pitched roof. An elaborate cornice and terra cotta balustrade (baked clay moulded into decorative patterns) expand on the decor of the tower."[8] Standpipe water towers were made obsolete by new pumping technology within the next decades, and the Bissell Tower was taken out of service in 1913.[8][9]

After Bissell Point plant was retired from service in 1960, its site was sold and subsequently became the location of the Metropolitan Sewer District's north sewage treatment plant, which began operations in 1970. A portion of the site is occupied by a city incinerator and garage.

The two north side water towers, as well as 1898's Compton Hill Tower, have been declared to be local and national landmarks and represent nearly half of all such surviving structures in the nation. Admirers of the north side towers have successfully resisted action to raze them and some funds are reported to be available for their restoration. In 1997 the Gateway Foundation had lighting added to the towers to light them at night. The effect has been stunning. The towers are now visible at night from the interstates and from many vantage points in their respective neighborhoods.[6]

Schools

The public schools which serve the area are Bryan Hill School at 2128 Gano Avenue, which was erected in 1912, and Lowell School at 1409 Linton Avenue, built in 1926 (now home to KIPP St. Louis Triumph Academy Charter School).

In September 2001, 1 of the 3 St. Louis Academies opened in College Hill at East Linton Avenue and 21st Street; this was the site of the former Perpetual Help Catholic School.[10]

Transportation

The College Hill area is currently served by four Bi-State bus lines. They are the Sarah Line, West Florissant Line, Grand Avenue Line, Vandeventer Line, and Broadway Line. The Sarah and Vandeventer Lines serve the western part of the City, including access to both St. Louis and Washington Universities. The West Florissant line provides transportation to North St. Louis County and Downtown St. Louis. The Broadway bus also provides transportation to parts of North County, Downtown, and South City. Once Downtown, passengers can transfer to the St. Louis Metro for access to the Airport, Clayton, and the East Side (Illinois). The Grand Avenue Line will provide transportation to points along Grand Avenue, including Grand Center, St. Louis University, and access to Grand Avenue stop of Metro.

Quick and easy access to Interstate 70, College Hill's northern border, is also available at the Adelaide Avenue, West Florissant, Broadway, and East Grand entrances and exits. Within minutes you can access the Downtown, the airport, and Interstates 55, 44 and 170. This quick access makes arriving at urban and outlying suburban destination convenient.[11]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 5,439 | — | |

| 2000 | 2,917 | −46.4% | |

| 2010 | 1,871 | −35.9% | |

| 2020 | 1,243 | −33.6% | |

| Sources:[12][13] | |||

In 2020, College Hill's racial makeup was 92.2% Black, 4.3% White, 0.5% Native American, 1.7% Asian, 1.6% two or more races, and 0.2% some other races. 0.6% of College Hill's population was of Hispanic or Latino origin.[14]

Crime

In 2015, The Guardian declared College Hill the most dangerous neighborhood in St. Louis.[15]

References

- ↑ "2020 Census Neighborhood Results".

- ↑ "Neighborhood Development and Early History, 1836 – 1890" (PDF). Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- ↑ "Neighborhood Development and Early History, 1836 – 1890" (PDF). Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- ↑ "Early (Pre 1900) St. Louis Places of Worship".

- ↑ "Neighborhood Development and Early History, 1836 – 1890" (PDF). Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- 1 2 3 "College Hill - Some Historic Elements". Archived from the original on 2011-06-07.

- ↑ History American Buildings Survey: North Grand Water Tower, North Grand & 20th Streets, Saint Louis, Saint Louis City County (sic), MO

- 1 2 Harris, NiNi (January 1986). "Treasured Towers". In Hannon, Robert E. (ed.). St. Louis: Its Neighborhoods and Neighbors, Landmarks and Milestones. St. Louis, MO: Buxton & Skinner Printing Co.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ↑ History American Buildings Survey: Red Water Tower, Blair & Bissell Streets, Saint Louis, Saint Louis City County (sic), MO

- ↑ "College Hill Schools". Archived from the original on 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "College Hill Transit". Archived from the original on 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "Baden Neighborhood Statistics". St Louis, MO. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ↑ "Neighborhood Census Data". City of St. Louis. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ↑ City of St. Louis (PL 94-171)

- ↑ Kendizor, Sarah (August 19, 2015). "'We're surrounded by murders': a day in St Louis's most dangerous neighborhood". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2015-08-19.