Lafayette Square | |

|---|---|

French style houses in a row face Lafayette Square Park | |

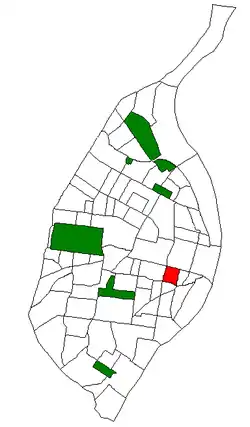

Location (red) of Lafayette Square within St. Louis | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Missouri |

| City | St. Louis |

| Wards | 6, 7 |

| Government | |

| • Aldermen |

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.34 sq mi (0.9 km2) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

| • Total | 2,164 |

| • Density | 6,400/sq mi (2,500/km2) |

| ZIP code(s) | Part of 63104 |

| Area code(s) | 314 |

| Website | lafayettesquare.org |

Lafayette Square is a neighborhood in St. Louis, Missouri, which is bounded on the north by Chouteau Avenue, on the south by Interstate 44, on the east by Truman Parkway, and on the west by South Jefferson Avenue.[2] It surrounds Lafayette Park (see below), which is the city's oldest public park — created by local ordinance in 1836.

The neighborhood is one of the oldest in St. Louis. When it was developed, it was one of the most fashionable places to live. It declined after a tornado devastated the area in 1896. Later, industrial encroachment and highway construction further weakened the neighborhood.

Since the 1970s, St. Louis residents have been buying and renovating the older homes in Lafayette Square. As of 2006, most of the homes have been restored and there are many shops and restaurants.

History

Since St. Louis’s beginning as a French village in 1764, the land which is now Lafayette Square had been a common pasture for village livestock and had never been privately owned. These commons became encampments for bands of criminals who would attack and rob area travelers. In 1835, now under American rule, Mayor Darby gained permission from the state legislature to begin selling the commons to drive the criminals out. When the city began to sell the common pasture, the Board of Aldermen set aside about 30 acres (120,000 m2) for community recreation. The square park was bordered by a street on each side, with the southern street called Lafayette in honor of Revolutionary War General Marie-Joseph-Paul-Roch-Yves-Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette, who had visited Saint Louis a few years previous during his famous 1824-25 tour of the United States.

In 1837 a real estate panic forced many who had bought land surrounding the Square to cease their payments, thereby causing the land to revert to the City. In the early 1850s, after courts had adjudicated the ownership of these properties, several prominent Saint Louisans bought most of the land bordering the southern end of the Park. These families built expensive homes along on Lafayette Avenue and secured state legislation preventing “any nuisance within a distance of 600 feet from the Park.” On November 12, 1851, the park was dedicated as “Lafayette Square” by City Ordinance 2741. By 1856, real estate developers had begun to sell lots on the western edge of the park—along Missouri Avenue—and by 1858 lots on the east side—Mississippi Avenue—were being sold. On Park Avenue—running along the north edge of the Square—the lots were developed by the 1870s.

From the 1850s to the 1870s money from neighborhood residents and city coffers went toward improvements of the Square. These included “trees, shrubbery, graveling, fencing[,]” and outdoor concerts. One newspaper called for more funds for improvement, writing that the Square “only needs to be properly improved to be one of the most attractive places in the United States.” During the American Civil War, Lafayette Square was spared from the riots that plagued other city parks. With the end of the war, martial law also ended, and lot purchasing picked up.

The first bandstand was constructed in 1867 coinciding with the opening of Benton Place—a private street (or, in the local terminology, "private place") off Park Avenue. In 1868, an historic crowd of 25,000 to 40,000 gathered to witness the unveiling of a bronze statue of Senator Thomas Hart Benton. The next year the park received one of the six casts of Houdon’s life-size marble sculpture of George Washington, who had fought alongside Lafayette. In the late 1860s, architect Francis Tunica’s design won a competition to build an iron fence—completed in 1869—around the Square. The newspaper the DAILY DEMOCRAT, June 27, 1870 wrote:

"In looking about the city and noting its improvements, we have been struck with the great progress attained in the vicinity of Lafayette Park. Within two years some of the finest residences in the city have been erected and the work is still going on. The beauty of the grounds, the elevation above the city, the character of the buildings, the beautiful shade trees, wide streets, and accessibility to the city by two lines of horse cars, the restrictions (by Statute) upon the erection of objectionable buildings or the carrying on of objectionable business, all combined should make this quarter the most desirable in the city for residence."

The 1870s was a time of flourishing for the Square marked by the continuing development of Benton Place on the north, and regular concerts on Thursdays and Sundays routinely attracting concertgoers numbering in the thousands and sometimes more than ten thousand. At one point, the park was tended to by thirteen gardeners. The 1880s and early 1890s were marked by organic growth of the neighborhood and increased importance of local churches and schools.

On May 27, 1896, Lafayette Square was largely destroyed by a tornado. The tornado did millions of dollars worth of damage, and killed many. The tornado uprooted nearly all of the trees in the Park as well as the trees on Benton Place, damaged the fence, destroyed the bandstand, destroyed the Union Club and the Methodist church at Jefferson and Lafayette Avenues, crippled the Presbyterian and Methodist churches, tore the roof off the Unitarian church, and crippled or destroyed many homes on the Square. Although some residents gave up on the neighborhood and moved away, others began to rebuild and by 1904 the Square had improved enough “to earn special commendation from foreign landscape architects who were visiting the World’s Fair.”

In 1923, the Missouri Supreme Court declared the 1918 residential zoning ordinance unconstitutional (see City of St. Louis v. Evraiff, 256 S.W. 489 (Mo. 1923)) and businesses began to purchase lots in the area. What the tornado of 1896 had begun, and the encroachment of gas stations and grocery stores continued, the Great Depression accelerated.

Lafayette Park

The 29.95-acre (121,200 m2) park was created by city ordinance 2741 in 1838. The park was named in honor of the Marquis de Lafayette (1757–1834), a French statesman who served as a volunteer under General George Washington in the Continental Army during the American Revolution.

The land was part of the St. Louis Common. When the Common was divided in 1836, an ordinance preserved the 29.95 acres for public use as a park. It was separated from the Commons in 1844 but it wasn't until 1851 that it was formally dedicated as Lafayette Square, the name that became associated with the neighborhood that grew up around the park. The park was renamed Lafayette Park in 1854. It also has cannons that were part of a British warship that bombarded Ft. Moultire in Charleston Harbor in June, 1776 during the Revolutionary War. The guns were placed in the park by the Missouri Commendry of the American Legion. In 1972, Lafayette Square was declared a historic district by Saint Louis. It has a few walking and biking trails, a duck pond with fountain, children's playground, various decorative plantings, and a gazebo that can be rented for picnics and events.[3]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 1,962 | — |

| 2000 | 1,761 | −10.2% |

| 2010 | 2,078 | +18.0% |

| 2020 | 2,164 | +4.1% |

| [4] | ||

In 2020 Lafayette Square's racial makeup was 77.7% White, 11.4% Black, 2.4% Asian, 7.3% Two or More Races, and 1.2% Some Other Race. 3.3% of the population was of Hispanic or Latino origin.[5]

| Racial composition | 1990[6] | 2000[7] | 2010[8] | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 74.8% | 68.4% | 80.5% | 77.7% |

| Black or African American | 24.2% | 28.1% | 13.5% | 11.4% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 1.4% | 3.0% | 3.3% | |

| Asian | 1.0% | 2.6% | 2.4% |

See also

- Lafayette Square Historic District (St. Louis)

- LaSalle Park, neighborhood between the Lafayette area and Soulard neighborhood

- Peabody–Darst–Webbe, St. Louis, neighborhood to the east of Lafayette Square

- Soulard, St. Louis, nearby area with a large public market

- Streetcars in St. Louis, Missouri, an early means of mass transit, to and from Lafayette Square

- Tower Grove Park, the large park constructed on private land, now public, a short distance west of Lafayette Square

References

- ↑ "2020 Census Neighborhood Results".

- ↑ Neighborhood Data Profile for Lafayette Square Archived 2007-11-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Lafayette Park, stlouis-mo.gov

- ↑ "Census".

- ↑ "City of St. Louis" (PDF). Retrieved 2021-09-16.

- ↑ "Lafayette Square Neighborhood Statistics". City of St. Louis.

- ↑ "The City of St. Louis Missouri". City of St. Louis.

- ↑ "The City of St. Louis Missouri". City of St. Louis.

Sources

- David T. Beito, "The Private Places of St. Louis," in Beito, Peter Gordon and Alex Tabarrok, The Voluntary City: Choice, Community, and Civil Society (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002), p. 47-75.

- John Albury Bryan, Lafayette Square: The Most Historic Old Neighborhood in St. Louis (2d ed. rev. Landmarks Assn. of St. Louis, Inc. 1969) (Lafayette Square Press 1962).

- Timothy G. Conley, Lafayette Square: An Urban Renaissance. Photography by Barbara Elliott Martin (Lafayette Square Press 1974).

- DAILY DEMOCRAT, June 27, 1870.

- Where We Live: A Guide To St. Louis Communities (Tim Fox ed. Missouri Historical Society Press 1995)

- Russell Kirk short story "Lex Talionis" which appears in Ancestral Shadows: An Anthology of Ghostly Tales

- National Register of Historic Places - Nomination Forms

- "Lafayette Square" (PDF). Missouri Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- "Lafayette Square Historic District" (PDF). Missouri Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

External links

- Lafayette Square - Lafayette Square website.

- Lafayette Square Photograph Collection at St. Louis Public Library