.jpg.webp)

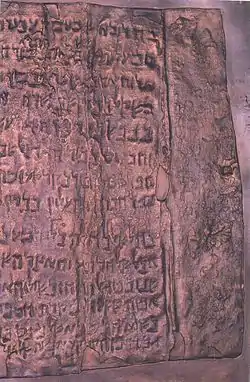

The Copper Scroll (3Q15) is one of the Dead Sea Scrolls found in Cave 3 near Khirbet Qumran, but differs significantly from the others. Whereas the other scrolls are written on parchment or papyrus, this scroll is written on metal: copper mixed with about 1 percent tin, although no metallic copper remained in the strips; the action of the centuries had been to convert the metal into brittle oxide.[1] The so-called 'scrolls' of copper were, in reality, two separated sections of what was originally a single scroll about 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) in length. Unlike the others, it is not a literary work, but a list of 64 places where various items of gold and silver were buried or hidden. It differs from the other scrolls in its Hebrew (closer to the language of the Mishnah than to the literary Hebrew of the other scrolls, though 4QMMT shares some language characteristics), its orthography, palaeography (forms of letters) and date (c. 50–100 CE, possibly overlapping the latest of the other Qumran manuscripts).[2]

Since 2013, the Copper Scroll has been on display at the newly opened Jordan Museum in Amman[3] after being moved from its previous home, the Jordan Archaeological Museum on Amman's Citadel Hill.

A new facsimile of the Copper Scroll by Facsimile Editions of London[4] was announced as being in production in 2014.[5]

History

While most of the Dead Sea Scrolls were found by Bedouins, the Copper Scroll was discovered by an archaeologist.[6] The scroll, on two rolls of copper, was found on March 14, 1952[7] at the back of Cave 3 at Qumran. It was the last of 15 scrolls discovered in the cave, and is thus referred to as 3Q15.[8] The corroded metal could not be unrolled by conventional means and so the Jordanian government sent it to Manchester University's College of Technology in England on the recommendation of English archaeologist and Dead Sea Scrolls scholar John Marco Allegro for it to be cut into sections, allowing the text to be read. He arranged for the university's Professor H. Wright Baker to cut the sheets into 23 strips in 1955 and 1956.[9] It then became clear that the rolls were part of the same document. Allegro, who had supervised the opening of the scroll, transcribed its contents immediately.

The first editor assigned for the transcribed text was Józef Milik. He initially believed that the scroll was a product of the Essenes but noted that it was likely not an official work of theirs. At first, he believed that it was not an actual historical account; he believed it was that of folklore. Later however, Milik's view changed. Since there was no indication that the scroll was a product of the Essenes from the Qumran community, he changed his identification of the scroll. He now believes that the scroll was separate from the community, although it was found at Qumran in Cave 3, it was found further back in the cave, away from the other scrolls. As a result, he suggested the Copper Scroll was a separate deposit, separated by a "lapse in time."[7]

Although the text was assigned to Milik, in 1957 the Jordanian Director of Antiquities approached Allegro to publish the text. After a second approach by a new director of Jordanian Antiquities,[10] Allegro, who had waited for signs of Milik of moving to publish, took up the second request and published an edition with translation and hand-drawn transcriptions from the original copper segments in 1960. Milik published his official edition in 1962, also with hand-drawn transcriptions, though the accompanying black-and-white photographs were "virtually illegible".[11] The scroll was re-photographed in 1988 with greater precision.[12] From 1994 to 1996, extensive conservation efforts by Electricité de France (EDF) included evaluation of corrosion, photography, x-rays, cleaning, making a facsimile and a drawing of the letters. Emile Puech's edition had the benefit of these results.[13]

Dating

Scholarly estimates of the probable date range of the Copper Scroll vary. Frank Moore Cross proposed the period of 25–75 CE[14] on palaeographical grounds, while William F. Albright suggested 70–135 CE.[15] Manfred Lehmann put forward a similar date range to Albright, arguing that the treasure was principally the money accumulated between the First Jewish–Roman War and the Bar Kokhba revolt, while the temple lay in ruins. P. Kyle McCarter Jr., Albert M. Wolters, David Wilmot and Judah Lefkovits all agree that the scroll originated around 70 CE.[7] Contrarily, Emile Puech argues that the Copper Scroll could not have been deposited behind 40 jars after they were already in place, so the scroll "predates 68 CE."[16]

Józef Milik proposed that the scroll was written around 100 CE.[7] If this dating is correct, it would mean that the scroll did not come from the Qumran community because the settlement had been destroyed by the Romans decades earlier.[14]

Language and writing style

The style of writing is unusual, different from the other scrolls. It is written in a style similar to Mishnaic Hebrew. While Hebrew is a well-known language, the majority of ancient Hebrew text in which the language is studied is generally biblical in nature, which the Copper Scroll is not. As a result, "most of the vocabulary is simply not found in the Bible or anything else we have from ancient times."[17] The orthography is unusual, the script having features resulting from being written on copper with hammer and chisel. There is also the anomaly that seven of the location names are followed by a group of two or three Greek letters, thought by some to represent numerical values.[18] Also, the "clauses" within the scroll mark intriguing parallels to that of Greek inventories, from the Greek temple of Apollo.[19] This similarity to the Greek inventories, would suggest that scroll is in fact an authentic "temple inventory."[19]

Some scholars believe that the difficulty in deciphering the text is perhaps due to it having been copied from another original document by an illiterate scribe who did not speak the language in which the scroll was written, or at least was not well familiar. As Milik puts it, the scribe "uses the forms and ligature of the cursive script along with formal letters, and often confuses graphically several letters of the formal hand."[20] As a result, it has made translation and understanding of the text difficult.

Contents

The text is an inventory of 64 locations; 63 of which are treasures of gold and silver, which have been estimated in the tons. For example, one single location described on the copper scroll describes 900 talents (868,000 troy ounces) of buried gold. Tithing vessels are also listed among the entries, along with other vessels, and three locations featured scrolls. One entry apparently mentions priestly vestments. The final listing points to a duplicate document with additional details. That other document has not been found.

The following English translation of the opening lines of the first column of the Copper Scroll shows the basic structure of each of the entries in the scroll. The structure is 1) general location, 2) specific location, often with distance to dig, and 3) what to find.

1:1 In the ruin that is in the valley of Acor, under

1:2 the steps, with the entrance at the East,

1:3 a distance of forty cubits: a strongbox of silver and its vessels

1:4 with a weight of seventeen talents. KεN[21][lower-alpha 1]

There is a minority view that the Cave of Letters might have contained one of the listed treasures,[22] and, if so, artifacts from this location may have been recovered. Although the scroll was made of alloyed copper in order to last, the locations are written as if the reader would have an intimate knowledge of obscure references. For example, consider column two, verses 1–3, "In the salt pit that is under the steps: forty-one talents of silver. In the cave of the old washer's chamber, on the third terrace: sixty-five ingots of gold."[23] As noted above, the listed treasure has been estimated in the tons. There are those who understand the text to be enumerating the vast treasure that was 'stashed,' where the Romans could not find it. Others still suggest that the listed treasure is that which Bar Kokhba hid during the Second Revolt.[14] Although it is difficult to estimate the exact amount, "it was estimated in 1960 that the total would top $1,000,000 U.S."[24]

Translation

Selected excerpts

[1] "In the ruin in the Valley of Achor, beneath the staircase that ascends towards the east [at a distance of] forty brick tiles there is a silver chest and its vessels, weighing seventeen talents"[lower-alpha 2]

According to Eusebius' Onomasticon, "Achor" – perhaps being a reference to an ancient town - is located to the north of Jericho.[25] However, in relation to the "Valley of Achor", Eusebius' view is rejected by most historical geographers, who place the "Valley of Achor" to the south of Jericho, either at the modern el-Buqei'ah, or at Wâdi en-Nu'eimeh.[26] Elsewhere, Eusebius places Emekachor (the Valley of Achor) near Galgal.[27] The "ruin in the valley of Achor" could be one of a number of sites: the ancient Beth-ḥagla,[lower-alpha 3] or what is also known as the "threshing floor of the Aṭad",[28] the most famous of all the ruins associated with the nation of Israel and being about two miles from the Jordan River, or else the ancient Beth Arabah,[29] and which John Marco Allegro proposed to be identified with 'Ain Gharabah,[30] while Robertson Smith proposed that it be identified with the modern 'Ain al-Feshkha,[31] or else Khirbet es-Sŭmrah, or Khirbet Qumrân. Another ruin at that time was the fortress Hyrcania, which had been destroyed some years earlier.

The Hebrew word אריח, translated here as "brick tiles", is used also in the Babylonian Talmud (BT) Megillah 16b and Baba Bathra 3b. The Hebrew word for "talents" is kikkarīn (ככרין). The weight of a talent varied with time and place. Amongst Jews in the early 2nd century CE, the kikkar was synonymous with the word maneh, a unit of weight that exceeds all others, divided equally into 100 parts.[32][lower-alpha 4] According to Epiphanius of Salamis, the centenarius (קנטינרא), a Latin loanword used in Hebrew classical sources for the biblical talent (kikkar), is said to have been a weight corresponding to 100 Roman librae.[33][lower-alpha 5][lower-alpha 6] The Hebrew word used for "chest" is שדה, a word found in Mishnah Keilim 15:1, ibid. 18:1, Mikva'ot 6:5, and explained by Hai Gaon in Mishnah Keilim 22:8 as meaning "an [ornamental] chest or trunk."[34]

[2] "In the [burial] monument, on the third course of stones there are one-hundred golden ingots"[lower-alpha 7]

There were several monuments of renown during the waning years of the Second Temple: that of Queen Helena, that of Yoḥanan the High Priest, both of which were in Jerusalem, or else outside the walls of the ancient Old City, etc. The Hebrew word used for "burial monument" is nefesh (נפש), which same word appears in Mishnah Sheqalim 2:5; Ohelot 7:1, and Eruvin 5:1, and which Talmudic exegete Hai Gaon explained as meaning "the building built over the grave; the same marker being a nefesh."[35][lower-alpha 8] The Hebrew word for "ingots" is 'ashatot (עשתות), its only equivalent found in Mishnah Keilim 11:3, and in Ezekiel 27:19, and which has the general meaning of "gold in its rawest form; an unshaped mass."[36][lower-alpha 9] Since no location is mentioned, most scholars think that this is a continuation of the previous section.[34]

[3] "In the great cistern within the courtyard of the peristyle, along the far-side of the ground, there are sealed-up within the hole [of the cistern's slab] (variant reading: within the sand), opposite its upper opening, nine-hundred talents."[lower-alpha 10]

The Hebrew word פרסטלון is taken from the Greek word περιστύλιον, meaning, "peristyle," a row of columns surrounding a space within a building. The word variantly read as ḥala (Imperial Aramaic: חלא, meaning "sand")[37] or ḥūliyya (חליא, meaning "small hole in the slab of stone that is laid over the mouth of a cistern"), is - in the latter case - a word found in BT Berakhot 3b and Sanhedrin 16a. The Hebrew word, as explained by Maimonides in his Judeo-Arabic Commentary of the Mishnah (Shabbat 11:2), connotes in Arabic, ḫarazat al-be'er – meaning, the round stone slab laid upon the cistern's mouth with a hole in the middle of the stone.[38] Since no specific location is mentioned, this section is thought to be a continuation of the previous two sections. Allegro surmised that this place may have been Khirbet Qumrân, where archaeologists have uncovered a watchtower, a water aqueduct, a conduit, and a very noticeable earthquake fissure which runs right through a large reservoir, besides also two courtyards, one of which containing a cistern.[39][34]

[4] "In the mound at Kuḥlith there are [empty] libation vessels, [contained] within a [larger] jar and new vessels (variant rendering: covered with ashes), all of which being libation vessels [for which a doubtful case had occurred], as well as the Seventh-Year store [of produce],[40] and the Second Tithe, lying upon the mouth of the heap, the entrance of which is at the end of the conduit towards its north, [there being] six cubits till [one reaches] the cavern used for immersion XAG"[lower-alpha 11]

The place-name Kuḥlith is mentioned in the Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 66a, being one of the towns in "the wilderness" that was conquered by Alexander Jannaeus (Yannai), whose military exploits are mentioned by Josephus in his Antiquities of the Jews (13.13.3–13.15.5). Its identification remains unknown, although Israeli archaeologist Boaz Zissu suggests that it is to be sought after in the Desert of Samaria.[41][lower-alpha 12]

Libation vessels, (כלי דמע, kelei dema', has the connotation of empty libation vessels that were once used to contain either vintage wine or olive oil, and given either to the priests or used in the Temple service, but which same produce was inadvertently mixed with common produce, and which rendered the whole unfit for the priests' consumption. The vessels themselves, however, remained in a state of ritual cleanness (Cf. Maimonides, Commentary on the Mishnah, Terumah 3:2; Hagigah 3:4). The word lagin (לגין) is a Greek loanword that found its way into the Hebrew language, derived from the Greek λάγηνος, and meaning simply an earthenware jar with handles. It is used in Mishnah Shabbat 20:2, Ohelot 5:5, Parah 10:2, Tevul Yom 4:4, et al. As for the word אפורין, it has been suggested that the word is a corruption of אנפורין, meaning "new vessels," just as it appears in Mishnah Baba Metzia 2:1, and explained in BT Baba Metzia 24a. If so, it is a loanword derived from the Greek έμπορία. The word may variantly be explained as "covered with ash." Others read the same text as a corruption of אפודם, "ephods". Though inconclusive, the idea of covering over such vessels with ashes was perhaps to distinguish these vessels from the others, so that the priests will not inadvertently eat of such produce, similar to the marking of a Fourth-year vineyard with clods of earth during the Seventh Year, so as not to cause unsuspecting people to transgress by eating forbidden produce when, normally, during that same year, all fruits that are grown become ownerless property.[lower-alpha 13][34]

[7] "In the old [burial] cave of Beit Ḥemdah (variant reading: Beit Hamara),[42] on the third stratum, [there are] sixty-five golden ingots."[lower-alpha 14]

In old Jewish parlance, as late as the Geonic period, the Hebrew word מערה (ma'arah, lit. "cave") signified a burial cave.[43][lower-alpha 15][44] Its linguistic use here, which is written in the construct state, i.e. "burial cave of…", points to that of a known place, Beit Ḥemdah (variant reading: Beit Hamara). The burial cave has yet to be identified. By "golden ingots" is meant "gold in its rawest form; an unshaped mass."[34]

[9] "In the cistern opposite the Eastern Gate, at a distance of nineteen cubits, therein are vessels and in the channel thereof are ten talents."[lower-alpha 16]

The "Eastern Gate" may be referring to what is now called the Golden Gate, a gate leading into the Temple Mount enclosure (cf. Mishnah, Middot 1:3),[45][lower-alpha 17] or it may be referring to the Eastern Gate, also known as the Nicanor Gate (and which some scholars hold to be the same as the "Corinthian gate" described by Josephus,[46] and alluded to in his Antiquities of the Jews),[47][lower-alpha 18][48][lower-alpha 19] in the Inner Court of the Temple precincts (cf. Mishnah, Berakhot 9:5).[50][lower-alpha 20]

In either case, the cistern was located on the Temple Mount, at a distance of 19 cubits from the gate (approximately 10 meters). The cistern may have been in disuse and was most-likely filled-in with stones and sealed. At present, there is no cistern shown at that distance from the Golden Gate on the maps listing the cisterns of the Temple Mount,[51][lower-alpha 21] which suggests that the cistern may have been concealed from view by filling it in with earth and stones. In contrast, if the sense is to the Nicanor Gate (which has since been destroyed), the cistern would have been that which is now called Bir er-rummâneh (Arabic: بئر الرمان, "the Pomegranate well"), being a large cistern situated on the southeast platform (nave) of the Dome of the Rock, measuring 55 by 4.5 metres (180 ft × 15 ft) and having a depth of 16 metres (52 ft), based on its proximity to the place where the Inner Court and its Eastern Gate once stood. The cistern, one of many in the Temple Mount, is still used today for storing water, and which Claude R. Conder and Conrad Schick connected with the "Water Gate" of the Inner Court mentioned in Mishnah Middot 1:4.[52] Entrance to the cistern is from its far eastern side, where there is a flight of stairs descending in a southerly direction. By "channel" (מזקא) is meant the conduit that directs water into the cistern.[53] Both Charles Warren and Conder noted the presence of a channel 5 ft (1.5 m) below the present surface layer of the Temple Mount, and which leads to the cistern now known as Bir el Warakah, situated beneath the Al-Aqsa mosque,[54] and which discovery suggests that the channel in question has been covered over by the current pavement. The end of the entry is marked by two Greek letters, ΔΙ (DI.[34]

[17] "Between the two houses (variant reading: two olive presses)[lower-alpha 22] that are in the Valley of Achor, in their very midst, buried to a depth of three cubits, there are two pots full of silver."[lower-alpha 23]

The term "the two houses" used here is unclear; it can be surmised that it may have meant an exact place between the two most famous towns that begin with the name "Beit", Beit Arabah[lower-alpha 24] and Beit-ḥagla.[lower-alpha 25] Both ancient places are in the Valley of Achor. Alternatively, Bethabara[lower-alpha 26] may have been intended as one of the "houses". The word that is used for "pots" (דודין, dūdīn) is the same word used in the Aramaic Targum for 'pots'.[59][34]

[21] "At the head of the aqueduct [that leads down to] Sekhakha, on its north side, be[neath a] large [stone],[lower-alpha 27] dig down [to a depth of [thr]ee cubits [and there are] seven silver talents."[lower-alpha 28]

A description of the ancient aqueducts near Jericho is brought down in Conder's and Herbert Kitchener's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP, vol. 3, pp. 206–207).[60] According to them, the natives knew of no such aqueducts south of Rujm el-Mogheifir. According to Lurie, the largest riverine gulch near Jericho with an aqueduct was Wadi Qelt (Wadi el Kelt), and which ran in an eastward direction, passing near Khirbet Kâkûn, whence it went down southwards about 4 km (2.5 mi) towards the end of Wadi Sŭweid.[61] Since the "head of the aqueduct" is mentioned, the sense here could imply the beginning of the aqueduct, which former takes its source from 'Ain Farah, 'Ain Qelt and 'Ain Fawâr and their surroundings, between Jerusalem and Jericho.[62] Conversely, the reference may have been to one of two other aqueducts built during the Second Temple period (and subsequently refurbished) and which take their beginnings from a water source at 'Ain el Aûjah ("the crooked spring"), the one termed Ḳanât el Manîl ("the canal of el Manil") which bears east towards an outlet in the Jordan valley north of Jericho, and the other termed Ḳanât Far'ûn ("Pharaoh's canal").[63][lower-alpha 29] Though inconclusive, the town of Sekhahka is thought by some scholars to be Khirbet Qumrân, which, too, had an aqueduct.[65][66][lower-alpha 30][34]

[24] "In the tomb that is in the riverine gulch of Ha-Kafa, as one goes from Jericho towards Sekhakha, there are buried talents [at a depth of] seven cubits."[lower-alpha 31]

The riverine gulch (נחל) that was once called Ha-Kafa has yet to be identified with complete certainty. The town Sekhakha, mentioned first in Joshua 15:61[29] and belonging to the tribe of Judah, also remains unidentified, although the Israeli Government Naming Committee has named a watercourse that rises from Khirbet es-Sumra and connects with Wadi Qumrân after its namesake. Scholars have suggested that Khirbet Qumrân is to be identified with the biblical Sekhakha.[65][67][66][34]

[26] "[In the ca]ve of the Column, which out of the two entranceways[lower-alpha 32] as one faces east, [at] the northern entrance, dig down three cubits, there is a [stone] jar in which is laid up one Book [of the Law], beneath which are forty-two talents."[lower-alpha 33]

Although the text is partially defaced, scholars have reconstructed it. The Hebrew word מערה (ma'arah, most likely used here in its most common sense, lit. "cave") is called here the "Cave of the Column", being a column that was well-known. The Hebrew word for "column" עמוד ('amūd) has not changed over the years, and is the same word used to describe a Gate of Jerusalem's Old City which stood in Roman times, although a newer Gate is now built above it with the same Arabic name, Bāb al-'Amoud (Damascus Gate), and which, according to Arabic legend/tradition, was called such in reference to a 14-metre (46 ft) high black marble column, which was allegedly placed in the inner courtyard of the door in the Roman and Byzantine period.[68] The 6th-century Madaba Map depicts in it artistic vignettes, showing what appears to be a black column directly within the one northern gate of the walled city. Both the old Roman Gate at Damascus Gate and Zedekiah's Cave are on the north-west side of the city. Although inconclusive, the cave that is referenced here may have actually been Zedekiah's Cave (a misnomer, being merely a meleke limestone quarry thought to have been used by Herod the Great), and may have been called such because of its proximity to the black marble column. Others, however, date the erection of this black marble column in that gate to Hadrian, when he named the city Aelia Capitolina. Nevertheless, the same cave is also known to have pillars (columns) that project from some of the rock to support a ceiling.[69] Today, Zedekiah's Cave lies between Damascus Gate and Herod's Gate, or precisely, some 152 metres (499 ft) to the left of Damascus Gate as one enters the Old City. The cave descends to a depth of 9.1 metres (30 ft) below the Old City, opening into a large antechamber, which is divided further on between two primary passageways. The leftmost passageway when entering the cave is the entranceway that faces "north" and which opens into a small recess. The identification here remains highly speculative, as Conder and Kitchener in their SWP also mention another place bearing the name Mŭghâret Umm el 'Amûd (Cave of the Pillars), along the south bank of Wadi Far'ah.[70] The Hebrew word for "jar" is קלל (qallal), and which Hai Gaon explains as meaning: "like unto a cask or jar that is wide [at its brim]."[71][lower-alpha 34] Such jars were, most-likely, made of stone, since they were also used to contain the ashes of the Red Heifer and which vessels could not contract uncleanness.[34]

[27] "In the queen's palace on its western side, dig down twelve cubits [and] there are twenty-seven talents."[lower-alpha 35]

Line 27 speaks about a queen (מלכה), rather than a king (מלך).[72] It is uncertain which queen is here intended, but the most notable of queens amongst the Jewish people during the late Second Temple period, and who had a palace built in Jerusalem, in the middle of the residential area known as Acra, was Queen Helena of Adiabene. The historian Josephus mentions this queen and her palace, "the palace of queen Helena," in his work The Jewish War (6.6.3.). The Hebrew word used here for "palace" is mishkan (משכן), literally meaning "dwelling place".[lower-alpha 36] Allegro incorrectly interpreted the word to mean "tomb," thinking it to be the queen's burial place.[73] As for the precise number of talents, Allegro, in his revised edition, reads there 7½, instead of 27, because of the unusual shape of the last numerical character.[74][34]

[32] "In Dok, beneath the corner of the eastern-most levelled platform [used for spreading things out to dry] (variant reading: guard-post), dig down to a depth of seven cubits, there are concealed twenty-two talents."[lower-alpha 37]</ref>

The ancient site of Dok is generally accepted to be the fortress Dok or Duq, mentioned in the First Book of Maccabees,[75] and which same name appears as Dagon in Josephus' Antiquities of the Jews (xiii, viii, 1), and in his book The Jewish War (i, ii, 3). Today, the site is more commonly known by its Arabic name, Jabal al-Quruntul, located about 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) west of Jericho and rising to an elevation of 366 metres (1,201 ft) above the level of the plain east of it. The site has been built and destroyed several times. In the year 340 CE, a Byzantine monastery named Duqa was built on the ruins of the old site, but it too was destroyed and has remained in ruins ever since.[76] According to Lurie, a town by the same name has existed at the foothills of the mountain, built alongside a natural spring.[77] Today, the site is known as Duyuk and is located roughly 2 km (1.2 mi) north of Jericho.[34]

[33] "At the source of the fountain head belonging to the Kuzeiba,[lower-alpha 38] (variant reading: Ḥaboba)[78] dig down [to a depth of] three cubits unto the bedrock (variant reading: toward the overflow tank),[79] [there are laid up] eighty [silver] talents [and] two golden talents."[lower-alpha 39]</ref>

The location of the Kuzeiba has yet to be positively identified, although there exists an ancient site by its name, now known as Khŭrbet Kûeizîba, a ruin that is described by Conder and Kitchener in ' 'SWP (vol. 3),[80][lower-alpha 40] a place situated to the south of Beit Fajjar and north of Siaîr, almost in their middle. A natural spring called 'Ain Kûeizîba is located nearby on the north-east side of the ruin.[34]

[35] "Within the heap of stones at the mouth of the ravine of the Kidron [brook] there are buried seven talents [at a depth of] three cubits."[lower-alpha 41]

The Kidron valley extends from Jerusalem to the Dead Sea, and its banks become more precipitous, in some places, as it progresses. The Hebrew word designating "heap of stones" is יגר (singular) and happens to be same word used by Jonathan ben Uzziel in his Aramaic Targum of Jeremiah 51:37, יגרין (plural).[34]

[43] "In the subterranean shaft that is on the north side of the mouth of the ravine belonging to Beth-tamar, as one leaves the 'Dell of the Labourer' (variant reading: as one leaves the small dale)[81] are [stored-away items] from the Temple Treasury made-up of things consecrated."[lower-alpha 42]

The sense of "mouth of the ravine" (פי הצוק) is generally understood to be the edge of a ravine. Beth-tamar has yet to be identified; although, in the days of Eusebius and Jerome, there was still a place by the name of Beththamar in the vicinity of Gaba, and which name was originally associated with Baal-tamar of Judges 20:33.[82][83] To this present day, towards the east of Gaba, there are still precipitous cliffs and a number of ancient sites (now ruins), one of which may have once borne the name Beth-tamar.[lower-alpha 43] Félix-Marie Abel thought to place Beth-tamar at Râs eṭ-Ṭawîl (grid position 172/137 PAL), a summit to the northeast of Tell el-Ful.[84] Others suggest that Beth-tamar is to be sought after around Jericho and Naaran, north of Jabal Kuruntul.[85]

It is to be noted that the old Aramaic Targum on Judges 20:33 translates Baal-tamar as "the plains of Jericho". The Hebrew word פלע has been translated here as "labourer," based on the cognate Hebrew-Aramaic-Arabic languages and the Hebrew linguistic tradition of sometimes interchanging ḥet (ח) with 'ayin (ע), as in ויחתר and ויעתר in BT, Sanhedrin 103a (see Minchat Shai on 2 Chronicles 33:13; Leviticus Rabba, sec. 30; Jerusalem Talmud, Sanhedrin 10:2). The word felaḥ (פלח) in Aramaic/Syriac has the connotation of "a worker; a labourer; an artisan; a husbandman; a vine-dresser; a soldier."[86] Lurie understood the same word as meaning "small", as in "the small dale".[81] The word for "things consecrated" is חרם and has the general connotation of things dedicated to the Temple, for which there is a penalty of death for one who committed sacrilege on these objects. An unspecified consecrated object belongs to the priests of Aaron's lineage, while consecrated things given to the Temple's upkeep (בדק הבית) are not the property of the priests.[87][34]

[44] "In the dovecote that is at the fortress of Nābaḥ which ... south, on the second storey as one descends from above, [there are] nine talents."[lower-alpha 44]

In the Land of Israel, dovecotes (columbariums) were usually constructed in wide, underground pits or caves with an air opening at the top, with geometric compartments for nesting pigeons built into the inner-walls and plastered over with lime. These were almost always built at a distance outside the city, in this case near the walled citadel or fort of Nabaḥ, a place that has yet to be identified. In Tosefta (Menachot 9:3), it is mentioned that, during the Second Temple period, fledglings of pigeons (presumably raised in dovecotes) were principally brought from the King's Mountain, meaning, from the mountainous regions of Judea and Samaria.[lower-alpha 45][34]

[45] "In the cistern [within] the dale of irrigation channels that are fed by the great riverine brook, in its ground floor [are buried] twelve talents."[lower-alpha 46]

Cisterns were large, bottle-shaped underground storage facilities[88] usually carved out of the limestone and used to store water. The large riverine brook can be almost any large gully or gorge (נחל) that drained the run-off winter rains into a lower region. The largest riverine brook nearest Jerusalem is Wadi Qelt, formerly known as Wadi Faran. The impression here is of a place that branches off from a larger brook, and where there are several irrigation channels that pass through it. Gustaf Dalman mentions several riverine brooks flowing, both, eastward and westward towards the Jordan River valley and irrigating large tracts of land along the Jordan valley.[89] The nearest place to Jerusalem that meets this description is the area known as the King's Garden, on the southern extremity of the City of David, where is the confluence of the Kidron Valley with a dale known as the Tyropoeon.[lower-alpha 47][34]

[46] "In the pool which is [in] Beit ha-kerem, as you approach on its left side, [buried] ten cubits, are sixty-two talents of silver."[lower-alpha 48]

French scholar A. Neubauer, citing the Church Father Jerome, writes that from Bethlehem one could see Bethacharma, thought to be the Beit HaKerem of Jeremiah,[90] and what is widely thought to have been near to Tekoa. Conder and Kitchener, however, both from the Palestine Exploration Fund, surmised that the site of Beth-haccerem was probably to be identified with 'Ain Kârim.[91] The Mishnah (compiled in 189 CE), often mentions Beit ha-kerem in relation to its valley, "the valley of Beit ha-kerem."[92] Today, the ancient site's identification remains disputed.[34]

[47] "In the lower millstone [of an olive press] belonging to the 'Dale of Olive' (variant reading: 'Dale of Provisions')[93][lower-alpha 49] on its western side, there are black stones [that] (variant reading: is a stone whose holes) [measure in depth] two cubits, being the entranceway, [in which are laid-up] three-hundred talents of gold and ten atonement vessels."[lower-alpha 50]

The Hebrew word yam (ים) denotes the "lower millstone" used in a stationary olive press. Its usage is found throughout the Mishnah.[lower-alpha 51] "Dale of the Olive" (גי זת, Gei Zayt, the word zayt meaning "olive") being written here in defective scriptum. Other texts write גי זוד instead of גי זת. Allegro was uncertain of its reading.[lower-alpha 52] Although there may have been several places by the name Gei Zayt in the 1st century CE, until the early 20th century, there still existed a place by this name in its Arabic form, "Khallat ez-Zeitūna," meaning, the "Dale of Olives," and it can only be surmised whether or not the Arabic name has preserved the original representation of the older Hebrew appellation, as there were likely other dales bearing the same name. "Khallat ez-Zeitūna" is shown on one of the old British Mandate maps of the region[94] and is located on the extreme eastern end of the Valley of Elah, where the western edge of the dale exits into the valley. Today, it is a narrow strip of farm land, flanked on both sides by hills, situated on the left-hand side of Moshav Aviezer as one enters the Moshav. Others read the text as "Dale of Provisions". The "black stones" are thought to be either basalt stones, which were carried there from far off, or "stones of bitumen."[95][34]

[51] "Beneath the corner of the [stone] bench projecting from the wall on the southside of Zadok’s tomb, underneath the stone column of the exedra, are found libation vessels [and] clothing [(the rest of the text is illegible)]"[lower-alpha 53]

According to Josephus (Antiquities 8.1.3.), Zadok was the first high priest during the reign of King David, and he continued to officiate in the Temple during Solomon’s reign.[96] The walled city of Jerusalem, at that time, occupied the site of the City of David. Since the burial custom of Israel was to bury outside the walls of the city, this would most-likely place the tomb of Zadok in or near the Kidron Valley, and perhaps even in the Tyropoeon Valley which, some years later, was incorporated within the city walls when it was encompassed by a wall (making it now a built-up area), or else in the Valley of Hinnom (Wadi er-Rababi), to the southwest of the City of David. The Hebrew word used for "stone-bench projecting from the wall" is esṭān, a variant spelling of esṭab (אסטאב), which same word appears in the Babylonian Talmud (Kiddushin 70a) as [אצטבא], explained there as a scholium, meaning "a bench," but of the kind traditionally made to project from a wall. After the words "libation vessels," the Hebrew word sūḥ [סוח] appears, and which Lurie believes refers to defiled things by reason of the images of the rulers (hence: אצלם) embossed on the coins offered to the Temple treasury.[97][34] The word sūḥ is derived from Isaiah 5:25, s.v. כסוחה. Milik, however, read the same word as sūth (סות), which Hebrew word is used in Genesis 49:11 to denote "clothing" or a "garment."[98] The remainder of the text is illegible in its current form. The second word, senaḥ (variant: senat) is left by Lurie without an explanation.

[60] "In the subterranean shaft that is [(incomprehensible text)][lower-alpha 54] on the north side of Kuḥlith, its northern entrance, there are buried at its mouth a copy of this writing and its interpretation and their measures, with a detailed description of each and every thing."[lower-alpha 55]

The words "subterranean shaft" (שית) appear under their Hebrew name in the Mishnah (Middot 3:3 and Me'ilah 3:3) and Talmud (Sukkah 48b),[lower-alpha 56] and where one of which was built near the sacrificial altar on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, down which flowed the blood and drink libations. The Hebrew word משחותיהם (meaning "their measures") is derived from the Aramaic word משחתא, being a translation of the Hebrew מדה in Exodus 26:8, among other places.[34]

Claims

The treasure of the scroll has been assumed to be treasure of the Jewish Temple, presumably the Second Temple, among other options.

The theories of the origin of the treasure were broken down by Theodor H. Gaster:[99]

- First, the treasure could be that of the Qumran community. The difficulty here is that the community is assumed to be an ascetic brotherhood, with which vast treasures are difficult to reconcile. (Yet community, as opposed to individual, wealth for a future hoped-for temple is possible. Such is proposed by, among others, André Dupont-Sommer, Stephen Goranson, and Emile Puech.)

- Second, the treasure could be that of the Second Temple. However, Gaster cites Josephus as stating that the main treasure of the Temple was still in the building when it fell to the Romans, and also that other Qumranic texts appear to be too critical of the priesthood of the Temple for their authors to have been close enough to take away their treasures for safekeeping. (The Arch of Titus shows some Temple items taken to Rome.)

- Third, the treasure could be that of the First Temple, destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon, in 586 BCE. This would not seem to fit with the character of the other scrolls, unless perhaps the scroll was left in a cave during the Babylonian Exile, possibly with a small community of caretakers who were precursors of the Dead Sea Scrolls community. (The scroll was written too late for this proposal.)

- Fourth, Gaster's own favourite theory is that the treasure is a hoax.

There are other options besides those listed by Gaster.[lower-alpha 57] For instance, Manfred Lehmann considered it Temple contributions collected after 70 CE.

Scholars are divided as to what the actual contents are. However, metals such as copper and bronze were a common material for archival records. Along with this, "formal characteristics" establish a "line of evidence" that suggest this scroll is an authentic "administrative document of Herod's Temple in Jerusalem."[19] As a result, this evidence has led a number of people to believe that the treasure really does exist. One such person is John Allegro, who in 1962 led an expedition. By following some of the places listed in the scroll, the team excavated some potential burial places for the treasure. However, the treasure hunters turned up empty handed,[14] and any treasure is yet to be found.

Even if none of the treasures comes to light, 3Q15, as a new, long ancient Hebrew text has significance; for instance, as comparative Semitic languages scholar Jonas C. Greenfield noted, it has great significance for lexicography.[100]

It is more than plausible that the Romans discovered the treasure. Perhaps, when the temple of Herod was destroyed, the Romans went looking for any treasure and riches the temple may have had in its possession.[19] The Romans might easily have acquired some or all of the treasure listed in the Copper Scroll by interrogating and torturing captives, which was normal practice. According to Josephus, the Romans had an active policy regarding the retrieval of hidden treasure.[19]

Another theory is that, after the Roman army left after the siege, Jewish people used the Copper Scroll to retrieve the valuables listed, and spent the valuables on rebuilding Jerusalem.[101]

Media

- A Long Way to Shiloh (known as The Menorah Men in the US) is a thriller by Lionel Davidson, published in 1966, whose plot follows the finding and contents of a similar treasure scroll.

- The denouement of Edwin Black's Format C: included using the Copper Scroll to find the Silver Scroll, giving the protagonists the information they needed to find and defeat the main threat of the book.

- The Copper Scroll is the subject of a political thriller, The Copper Scroll, by Joel C. Rosenberg, published in 2006. The book uses Rosenberg's theory that the treasures listed in the Copper Scroll (and the Ark of the Covenant) will be found in the End Times to refurnish the Third Temple.

- The Copper Scroll also features in Sean Young's historical novel, Violent Sands, in which Barabbas is the sworn protector of the Copper Scroll and the treasure it points to.

- The scroll—and a search for its treasures—was featured in a 2007 episode of the History Channel series Digging for the Truth. The program gives a basic knowledge of the research of the Copper Scroll and all the major theories of its interpretation.

Gallery

Strips of the Copper Dead Sea Scroll at the Jordan Museum, from Qumran Cave 3, 1st century CE

Strips of the Copper Dead Sea Scroll at the Jordan Museum, from Qumran Cave 3, 1st century CE Strip 11 of the Copper Dead Sea Scroll, from Qumran Cave 3, Jordan Museum

Strip 11 of the Copper Dead Sea Scroll, from Qumran Cave 3, Jordan Museum Strip 13 of the Copper Dead Sea Scroll, from Qumran Cave 3, Jordan Museum

Strip 13 of the Copper Dead Sea Scroll, from Qumran Cave 3, Jordan Museum Strip 15 of the Copper Dead Sea Scroll, from Qumran Cave 3, Jordan Museum

Strip 15 of the Copper Dead Sea Scroll, from Qumran Cave 3, Jordan Museum Strip 18 of the Copper Dead Sea Scroll, from Qumran Cave 3, Jordan Museum

Strip 18 of the Copper Dead Sea Scroll, from Qumran Cave 3, Jordan Museum

See also

Notes

- ↑ The three letters at the end are Greek.

- ↑ Original Hebrew: בחרובהא שבעמק עכור תחת המעלות הבואת למזרח אמות אריח ארבעין שדת כסף וכליה משקל ככרין שבעשרה ΚΕΝ

- ↑ The name has been variously interpreted. James Elmer Dean, editor of the Syriac version of Epiphanius' Treatise On Weights and Measures interprets it as meaning "the place of the circuit," in recognition of the circuits made there by Joseph and his brothers who stopped there while en route to the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron. E.H. Palmer of the Palestine Exploration Fund, on the other hand, interprets it as meaning - based on the Arabic - "the house of the partridge."

- ↑ s.v. ככר כסף; cf. Epiphanius of Salamis (c. 310–403), who explains the sense of certain Hebrew weights and measures and writes: "The talent is called Maneh (mina) among the Hebrews," the equivalence of 100 coins in specie. See: Epiphanius (1935). James Elmer Dean (ed.). Epiphanius' Treatise on Weights and Measures - The Syriac Version. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 60 (§ 51), 65. OCLC 123314338.

- ↑ The weight of the Roman libra is estimated at anywhere from 322–329 g (11.4–11.6 oz). One-hundred Roman libra would have come to 32.89 kilograms (72.5 lb), roughly the same figure proposed by Shelley Neese of The Copper Scroll Project for the weight of the talent. Lefkovits (1994,37) supposed that the weight of the talent in the late Second Temple period was equal to about 21.3 kilograms (47 lb). Adani (1997), p. 17b, claims that for every talent there were 6,000 denaria, having a total weight of 27.338 kilogram.

- ↑ Jerusalem Talmud (Sanhedrin, end of chapter 1, s.v. שאל אנטינונס הגמון לרבן יוחנן בן זכאי); ibid, Commentary of Moses Margolies entitled Pnei Moshe. Here, centenarius (קנטינרא) is used interchangeably with the Hebrew "talent" (kikkar). Compare Josephus, Antiquities 3.6.7. (3.144) "Over against this table, near the southern wall, was set a candlestick of cast gold, hollow within, being of the weight one-hundred [pounds], which the Hebrews call Chinchares (Ancient Greek: κίγχαρες) (Hebrew: קינטרא); if it be turned into the Greek language, it denotes a talent."

- ↑ Original Hebrew: בנפש בנדבך השלישי עשתות זהב מאה

- ↑ s.v. נפש אטומה (Ohelot 7:1)

- ↑ s.v. העשת (Keilim 11:3), where Hai Gaon writes: "ha-'ashet, meaning, a large piece of [unshaped] metal, as it is written (Ezekiel 27:19): Dan and Yavan gave yarn for thy wares, [unshaped] smelted iron."

- ↑ Original Hebrew: בבור הגדול שבחצר הפרסטלון בירכ קרקעו סתומ בחלא נגד הפתח העליון ככרין תשע מאת

- ↑ Original Hebrew: בתל של כחלת כלי דמע בלגין ואפורין הכל של דמע והאוצר השבוע ומעסר שני בפי גל פתחו בשולי האמא מן הצפון אמות שש עד ניקרת הטבילה ΧΑΓ

- ↑ Zissu's identification is based on a similarity of its name with Wadi Kuḥeila, a watercourse that empties into the larger watercourse by the name of Wādi Sāmiya, from its north side. The watercourse appears in the Palestine Open Maps, and although no ruin by that name has been found, there is a possibility that its old appellation was changed in later time by a newer name. A nearby ruin along the watercourse is Kh. Samiya, near the confluence of Wadi Samiya and Wadi Siya.

- ↑ Cf. BT Baba Kama 69a.

- ↑ במערת בין חמדה הישן ברובד השלישי עשתות זהב ששין וחמש ΘΕ

- ↑ s.v. מערה

- ↑ Original Hebrew: בבור שנגד השער המזרחי רחוק אמות תשעסרא בו כלין ובמזקא שבו ככרין עסר ΔΙ

- ↑ s.v. Middot 1:3.

- ↑ Cf. Mishnah Shekalim 6:3; Sotah 1:5; Middot 1:4, 2:6; Tosefta Yom ha-kippurim 2:4

- ↑ s.v. קלנתיא. See also a discussion on this subject in the Jewish Virtual Library, s.v. Nicanor's Gate.[49]

- ↑ s.v. Berakhot 9:5. See Maimonides' commentary there.

- ↑ The closest cistern at present to the Golden Gate, if it were indeed the Eastern Gate under discussion here, lies at a distance of some 30–40 m (98–131 ft) to its west, northwest.

- ↑ Allegro (1960), p. 39, renders these words as שני הבדין, meaning "two olive presses." In Allegro's revised second edition, published in 1964, p. 22, he wrote for the same words "two buildings".

- ↑ Original Hebrew: בין שני הבתין שבעמק עכון באמצענ חפון אמות שלוש שמ שני דודין מלאין כסף

- ↑ Beit Arabah, although mentioned three times in the Hebrew Scriptures, has not yet been positively identified. Some think that it may have been where is now 'Ain el-Gharabeh, a site that has not yielded archaeological artifacts any earlier than the Byzantine period, while others think that it is to be identified with Rujm el-Bahr.[55]

- ↑ Beit-ḥagla (ΒΗΘΑΓΛΑ) is shown on the Madaba Map a little south-east of Jericho. Eusebius, in his Onomasticon, wrote of the site being located at "three milestones from Jericho and about two milestones from the Jordan".[56] The old site of Beit-ḥagla may have been near the adjacent natural spring by the name 'Ein Ḥajla, located a little more than 1 km (0.62 mi) to the north-east of the monastery Deir Hajla.[57]

- ↑ Bethabara is a site shown on the Madaba Map (ΒΕΘΑΒΑΡΑ) on the west bank of the Jordan River, not far from the place where it empties into the Dead Sea. Some identify this site with the modern Tell Medes, and others with Makhadet el Hajla, not far from Beit-ḥagla.[58]

- ↑ Allegro, in his revised second edition (1964, p. 23), leaves this space blank, as it is clearly defaced in the original copper scroll. There is no evidence what the reference may have been, whether to a large stone, or large tree, etc.

- ↑ Original Hebrew: ברוש אמת המימ [... ]סככא מן הצפון ת[...] הגדולא חפור אמ[...]ש כספ ככ שבעה

- ↑ Wadi el Aujah is shown on the Palestine Exploration Fund map (SWP map no. XV.[64]

- ↑ The number "seven" is represented in the original text by the symbols of seven vertical lines, although part of the original text of the Copper Scroll was defaced at the end of the seventh vertical line.

- ↑ Original Hebrew: בקבר שבנחל הכפא בבואה מירחו לסככא חפון אמות שבע ככ

- ↑ Follows Lurie's interpretation. Allegro (1964), p. 23, writes here "Double Gate," which is clearly a mistranslation. The Hebrew word for city gate is sha'ar (שער), whereas the word used here is פתחין petaḥīn, meaning, "entranceways".

- ↑ Original Hebrew: ...רת העמוד של שני ...פתחין צופא מזרח ...פתח הצפוני חפור ...מות שלוש שמ קלל בו ספר אחד תחתו ככ ॥ᑎᑎ

- ↑ Mishnah Parah 3:3, s.v. קלל של חטאת

- ↑ Original Hebrew: במשכן המלכא בצד המערבי חפר אמות שתימ עסרה ככ ᑎ।।।।।।।

- ↑ Cf. Saadia Gaon's Judeo-Arabic translation of the Pentateuch (Numbers 24:5), where the Hebrew word משכנתיך, meaning משכנות, plural of משכן, is explained by him as meaning "dwellings; houses", and being equivalent to the Arabic word منازل. The Hebrew word is said to be derived from the Phoenician škn (meaning "dwelling place"), and from the Akkadian maškanu (meaning "place"), and related to the Aramaic/Syriac mškn (meaning "tent; dwelling").

- ↑ Original Hebrew: בדוק תחת פנת המשטח המזרחית חפור אמות שבע ככ שתימ ועשרים. In the original Hebrew, the number "twenty-two" is represented by the ancient numerical symbols: ।।э

- ↑ Lefkovits, J. (1994), p. 534, holds this to be the correct reading, following the opinion of Józef Milik, Bargil Pixner and Thorion. In Allegro's first edition of his translation of the Copper Scroll (1960, p. 45), he assumed that the word referenced here was "drain pipe." In Allegro's second revised edition (1964, p. 24) he corrected his translation to read "Kozibah" (Kuzeiba).

- ↑ Original Hebrew: על פי יציאת המימ של הכוזבא חפור אמות שלוש עד הסור ככ ээээ זהב ככרינ שתימ. In the original Hebrew, the number "eighty" is represented by three ancient numerical symbols: ээээ

- ↑ Khŭrbet Kûeizîba is described as the "ruins of a small town with a good spring. The buildings stand on terraces on the side of the valley, and some of the walls remain to a height of 10 feet. In the upper part of the ruin is a tower of good sized masonry, some of the stones 4 feet long. The masonry is good, and has the appearance of antiquity; the ruin is unusually well preserved."

- ↑ Original Hebrew: ביגר של פי צוק הקדרון חפור אמות שלוש ככ שבעה

- ↑ Original Hebrew: בשית שו בצפון פי הצוק שלבית תמר בצהיאת גי פלע מלשכת חרמ

- ↑ Jeba (Gaba) and its topography were described in the late 19th-century by Conder and Kitchener of the Palestine Exploration Fund, in SWP (vol. 3, p. 9) as such: "...on the east [of Jeba] is a plain extending for about 1½ miles, and about ½ mile wide north and south. This plain is open arable land, extending to the brink of the precipitous cliffs on the north". These cliffs are seen on the maps of Palestine produced in the 1940s and are called 'Irāq el Husn, which rise from the banks of Wadi es Suweinit.

- ↑ Original Hebrew: בשובך שבמצד נאבח ה... דרומ בעליאה השנית ירידתו מלמעלא ככ תשעה

- ↑ The number "nine" is represented in the original text by the symbols of nine vertical lines.

- ↑ Original Hebrew: בבור גי מזקות שרוי מהנחל הגדול בקרקעו ככ ᑊᑊᐣ

- ↑ The number "twelve" is represented in the original text by two vertical lines.

- ↑ Original Hebrew: באשוח שו [ב]בית הכרמ בבואך לסמולו אמות עסר כסף ככרין ששין ושנין

- ↑ According to Lurie, the word which appears in the text is זוד), having the sense of "provisions" or "victuals" taken by a traveller on their journey.

- ↑ Original Hebrew: בימ של גי זת בצדו המערבי אבן שחורות אמות שתין הו הפתח ככרין שלש מאות זהב וכלין כופרין עסרה

- ↑ Cf. ים, yam, as explained by Mishnaic exegetes Hai Gaon (939–1038) on Mishnah (Taharot 10:8); Maimonides on Mishnah Baba Bathra 4:5 and in his Mishne Torah (Hil. Mekhirah 25:7) as pointed out by Rabbi Vidal of Tolosa; and by Nathan ben Jehiel (1035–1106) in his Sefer ha-Arukh, s.v. ממל; Obadiah Bartenura in his commentary on Mishnah (Maaserot 1:7), as well as by Moses Margolies (1715–1781) in his commentary P'nei Moshe on the Jerusalem Talmud (Baba Bathra 4:5), and by Nissim of Gerona on Rav Alfasi's commentary on Avodah Zarah 75a, among others. See also Amar, Z., Flora and Fauna in Maimonides' Teachings, Makhon ha-torah we-ha-aretz shavei darom, Kfar Darom 2015, p. 74 (in Hebrew), s.v. זית

- ↑ In Allegro's first translation of the Copper Scroll (1960, p. 51), he wrote "vat of the olive press." In his second revised edition (1964, p. 25), he wrote simply "Valley of [...]", leaving the word blank.

- ↑ Original Hebrew: מתחת פנת האסטאן הדרוימית בקבר צדוק תחת עמוד האכסדרן כלי דמע סוח דמע סנח ותכן אצלמ

- ↑ Allegro (1960), p. 55, renders this word שכינה as "adjoining," although there is no parallel to its usage in rabbinic writings that show for it a lineal reference to distance. What is more, the word is partially defaced in the original scroll.

- ↑ Original Hebrew: בשית שבינח בצפון כחלת פתחא צפון וקברין על פיה משנא הכתב הזה ופרושה ומשחותיהמ ופרוט כל אחד ואחד

- ↑ See also Maimonides, Mishne Torah (Hil. Ma'aseh Korbanot 2:1)

- ↑ See Wolters in Bibliography pp. 15–17 for a more up-to-date list

References

- ↑ J.T. Milik, The Copper Document from Cave III, Qumran, p. 61

- ↑ "The Bible and Interpretation – On the Insignificance and the Abuse of the Copper Scroll". Bibleinterp.com. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- ↑ "Новости – Библейский альманах "Скрижали"". Luhot.ru. 2013-07-29. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- ↑ "Dead Sea Scrolls". Facsimile Editions. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- ↑ "Copied copper scroll is one to treasure". The Jewish Chronicle. 5 September 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ↑ Lundberg, Marilyn J. "The Copper Scroll (3Q15)". West Semitic Research Project. Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Wise, Michael (2005). A New Translation: The Dead Sea Scrolls. New York: Harper Collins Publisher. pp. 211–223. ISBN 978-0-06-076662-7.

- ↑ Archived February 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Allegro 1960, pp. 22–24, 27.

- ↑ Allegro, 1960, p. 6.

- ↑ Al Wolters, article on the "Copper Scroll", in Schiffman, 2000a (Vol.2), p.146.

- ↑ George J. Brooke; Philip R. Davies (2004). Copper Scroll Studies. A&C Black. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-567-08456-9. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- ↑ See Poffet, et al. 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 VanderKam, James C. (2010). The Dead Sea Scrolls Today. Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-8028-6435-2.

- ↑ Al Wolters, article on the "Copper Scroll", in Schiffman, 2000a (Vol.2), p.146.

- ↑ Puech, "Some Results of the Restoration of the Copper Scroll by EDF Mecenat", in Schiffman, 2000b, p.893.

- ↑ Lundberg, Marilyn J. "The Copper Scroll (3Q15)". West Semitic Research Project. Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ Lefkovits (1994), p. 123

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wise, Abegg, and Cook, Michael, Martin, and Edward (2005). A New Translation: The Dead Sea Scrolls. New York: Harper Collins Publisher. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-06-076662-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Milik, J.T (September 1956). "The Copper Document from Cave III, Qumran". The Biblical Archaeologist. 19 (3): 60–64. doi:10.2307/3209219. JSTOR 3209219. S2CID 165466511.

- ↑ Wise, Abegg, and Cook, Michael, Martin, and Edward (2005). A New Translation: The Dead Sea Scrolls. New York: Harper Collins Publisher. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-06-076662-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "NOVA | Ancient Refuge in the Holy Land". Pbs.org. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- ↑ Wise, Abegg, and Cook, Michael, Martin, and Edward (2005). A New Translation: The Dead Sea Scrolls. New York: Harper Collins Publisher. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-06-076662-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Lundber, Marilyn. "The Copper Scroll (3Q15)". West Semitic Research Project. Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ Chapmann III, R.L.; Taylor, J.E., eds. (2003). Palestine in the Fourth Century A.D.: The Onomasticon by Eusebius of Caesarea. Translated by G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville. Jerusalem: Carta. pp. 19, 169. ISBN 965-220-500-1. OCLC 937002750.

- ↑ Chapmann III, R.L.; Taylor, J.E., eds. (2003). Palestine in the Fourth Century A.D.: The Onomasticon by Eusebius of Caesarea. Translated by G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville. Jerusalem: Carta. p. 104. ISBN 965-220-500-1. OCLC 937002750.

- ↑ Chapmann III, R.L.; Taylor, J.E., eds. (2003). Palestine in the Fourth Century A.D.: The Onomasticon by Eusebius of Caesarea. Translated by G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville. Jerusalem: Carta. p. 50. ISBN 965-220-500-1. OCLC 937002750.

- ↑ Genesis 50:10

- 1 2 Joshua 15:61

- ↑ Allegro (1964), p. 63

- ↑ Jewish Encyclopedia (1906), s.v. Beth-Arabah

- ↑ Pesikta de-Rav Kahana (1949). Salomon Buber (ed.). Pesikta de-Rav Kahana. New York: Mekitze Nirdamim. p. 19a (P. Sheqalīm). OCLC 122787256.

- ↑ Epiphanius (1935). James Elmer Dean (ed.). Epiphanius' Treatise on Weights and Measures - The Syriac Version. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 57. OCLC 123314338.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Lurie, Benzion, ed. (1964). The Copper Scroll from the Judean Desert (megīllat ha-neḥoshet mimidbar yehūdah) (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: The Society for biblical research in Israel, in affiliation with Kiryat Sefer Publishing House. OCLC 233295816.

- ↑ Hai Gaon (1921–1924), "Hai Gaon's Commentary on Seder Taharot", in Epstein, J.N. (ed.), The Geonic Commentary on Seder Taharot - Attributed to Rabbi Hai Gaon (in Hebrew), vol. 2, Berlin: Itzkowski, p. 85, OCLC 13977130

- ↑ Hai Gaon (1921–1924), "Hai Gaon's Commentary on Seder Taharot", in Epstein, J.N. (ed.), The Geonic Commentary on Seder Taharot - Attributed to Rabbi Hai Gaon (in Hebrew), vol. 1, Berlin: Itzkowski, p. 20, OCLC 13977130

- ↑ Lurie, B. (1964), p. 61

- ↑ Maimonides (1963). Mishnah, with Maimonides' Commentary (in Hebrew). Vol. 1. Translated by Yosef Qafih. Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook. p. 38 (part II). OCLC 741081810.

- ↑ Allegro (1964), pp. 64–65

- ↑ Lehman, Manfred R. (1964). "Identification of the Copper Scroll Based on its Technical Terms". Revue de Qumrân. Peeters Publishers. 5 (1): 97–105. JSTOR 24599088.

- ↑ Zissu, Boaz [in Hebrew] (2001). "The Identification of the Copper Scroll's Kaḥelet at 'Ein Samiya in the Samarian Desert". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 133 (2): 145–158. doi:10.1179/peq.2001.133.2.145. S2CID 162214595.

- ↑ Lurie, B. (1964), p. 68

- ↑ Ratzaby, Yehuda [in Hebrew] (1978). Dictionary of the Hebrew Language used by Yemenite Jews (Osar Leshon Haqqodesh shellivne Teman) (in Hebrew). Tel-Aviv. p. 166. OCLC 19166610.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Lurie, B. (1964), p. 93 (note 204)

- ↑ Danby, H., ed. (1933), The Mishnah, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 590, ISBN 0-19-815402-X

- ↑ Josephus, The Jewish War 5.204

- ↑ 15.11.5.

- ↑ Jastrow, M., ed. (2006), Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature, Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers, p. 1379, OCLC 614562238

- ↑ Jewish Virtual Library

- ↑ Danby, H., ed. (1933), The Mishnah, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 10, ISBN 0-19-815402-X

- ↑ Schiller, Eli [in Hebrew], ed. (1989). The Temple Mount and its Sites (הר הבית ואתריו) (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Ariel. pp. 129–134 (Cisterns on the Temple Mount). OCLC 741174009. (Reproduced from Ariel: A Journal for the Knowledge of the Land of Israel, volumes 64-65).

- ↑ Schiller, Eli [in Hebrew], ed. (1989). The Temple Mount and its Sites (הר הבית ואתריו) (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Ariel. p. 131 (Cisterns on the Temple Mount). OCLC 741174009. (Reproduced from Ariel: A Journal for the Knowledge of the Land of Israel, volumes 64-65).

- ↑ Wolters, A. (1989). "The 'Copper Scroll' and the Vocabulary of Mishnaic Hebrew". Revue de Qumrân. Leuven (Belgium): Peeters. 14 (3 (55)): 488. JSTOR 24608995., items 2:9 and 10:3

- ↑ London 1884, p. 220

- ↑ Chapmann III, R.L.; Taylor, J.E., eds. (2003). Palestine in the Fourth Century A.D.: The Onomasticon by Eusebius of Caesarea. Translated by G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville. Jerusalem: Carta. p. 121. ISBN 965-220-500-1. OCLC 937002750.

- ↑ Chapmann III, R.L.; Taylor, J.E., eds. (2003). Palestine in the Fourth Century A.D.: The Onomasticon by Eusebius of Caesarea. Translated by G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville. Jerusalem: Carta. pp. 14, 179. ISBN 965-220-500-1. OCLC 937002750.

- ↑ Marcos, Menahem (1979). "'Ain Hajla". In Ben-Yosef, Sefi (ed.). Israel Guide - The Judean Desert and The Jordan Valley (A useful encyclopedia for the knowledge of the country) (in Hebrew). Vol. 5. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, in affiliation with the Israel Ministry of Defence. p. 169. OCLC 745203905.

- ↑ Chapmann III, R.L.; Taylor, J.E., eds. (2003). Palestine in the Fourth Century A.D.: The Onomasticon by Eusebius of Caesarea. Translated by G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville. Jerusalem: Carta. p. 120. ISBN 965-220-500-1. OCLC 937002750.

- ↑ Cf. II Kings 4:38, Zechariah 14:20, et al.

- ↑ Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund., pp. 206–207

- ↑ Lurie (1964), p. 85

- ↑ Ben-Yosef, Sefi (1979). "Wadi Qelt". In Yitzhaki, Arieh (ed.). Israel Guide - The Judean Desert and The Jordan Valley (A useful encyclopedia for the knowledge of the country) (in Hebrew). Vol. 5. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, in affiliation with the Israel Ministry of Defence. pp. 76–82. OCLC 745203905.

- ↑ Ben-Yosef, Sefi (1979). "Wadi Auja". In Yitzhaki, Arieh (ed.). Israel Guide - The Judean Desert and The Jordan Valley (A useful encyclopedia for the knowledge of the country) (in Hebrew). Vol. 5. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, in affiliation with the Israel Ministry of Defence. pp. 73–74. OCLC 745203905.

- ↑ XV

- 1 2 Allegro (1960), pp. 68–74, 144–145

- 1 2 Ben-Yosef, Sefi (1979). "Ḥorvat Chariton". In Yitzhaki, Arieh (ed.). Israel Guide - The Judean Desert and The Jordan Valley (A useful encyclopedia for the knowledge of the country) (in Hebrew). Vol. 5. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, in affiliation with the Israel Ministry of Defence. p. 88. OCLC 745203905.

- ↑ Allegro (1964), pp. 63–70 (Chapter Seven)

- ↑ cf. Le Strange (1965), Palestine under the Moslems: a Description of Syria and the Holy Land from AD 650 to 1500, p. 214, who cites Idrisi (1154) over this tradition.

- ↑ Quarrying History in Jerusalem, The New York Times (December 1, 1985)

- ↑ Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. p. 243.

- ↑ Hai Gaon (1924), "Hai Gaon's Commentary on Seder Taharot", in Epstein, J.N. (ed.), The Geonic Commentary on Seder Taharot - Attributed to Rabbi Hai Gaon (in Hebrew), vol. 2, Berlin: Itzkowski, p. 103, OCLC 13977130

- ↑ Høgenhaven (2015), p. 277, s.v. item 6:11

- ↑ Allegro (1964), p. 23 (item no. 28); Allegro (1960), p. 43 (item no. 28)

- ↑ Allegro (1964), p. 23 (item no. 28)

- ↑ 1 Maccabees 16:15

- ↑ Ben-Yosef, S. (1979), p. 55

- ↑ Lurie, B. (1964), p. 97.

- ↑ Lurie, B. (1964), p. 97

- ↑ Allegro (1964), p. 24

- ↑ Conder, C.R; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. p. 358.

- 1 2 Lurie (1964), p. 111

- ↑ Judges 20:33

- ↑ Chapmann & Taylor (2003), pp. 37, 117, s.v. Baalthamar

- ↑ Allegro (1960), p. 158 (note 222)

- ↑ Lefkovits (1994), p. 114

- ↑ Payne Smith, R. (1903). Jessie Margoliouth (ed.). A Compendious Syriac Dictionary (in Syriac and English). Oxford. p. 448.

ܦܠܚ a labourer, a husbandman, a vine-dresser

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Nathan ben Abraham (1955), "Perush Shishah Sidrei Mishnah - A Commentary on the Six Orders of the Mishnah", in Sachs, Mordecai Yehudah Leib (ed.), The Six Orders of the Mishnah: with the Commentaries of the Rishonim (in Hebrew), Jerusalem: El ha-Meqorot, OCLC 233403923, s.v. Tractate Nedarim

- ↑ Dalman, Gustaf (2013). Work and Customs in Palestine. Vol. I/2. Translated by Nadia Abdulhadi Sukhtian. Ramallah: Dar Al Nasher. pp. 541–543. ISBN 9789950385-01-6. OCLC 1040774903.

- ↑ Dalman (2020), p. 277.

- ↑ Neubauer's Geography: Adolphe Neubauer, La Géographie du Talmud, Paris 1868, pp. 131 – 132, s.v. Jerome, Comm. ad Amos, VI, 1

- ↑ Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. p. 20.

- ↑ Mishnah Middot 3:4; Niddah 2:7.

- ↑ Lurie (1964), p. 115.

- ↑ Palestine Open Maps, Palestine 1940s. The dale passes between the upper Kh. Umm er Rūs and the lower Kh. Umm er Rūs.

- ↑ Lurie (1964), p. 115

- ↑ Josephus (Antiquities 10.8.6.)

- ↑ Lurie (1964), pp. 118–119

- ↑ Targum Onkelos on Gen. 49:11; Midrash ha-Hefez on Gen. 49:11

- ↑ Theodor H. Gaster (1976). The Dead Sea Scriptures. Peter Smith Publishing Inc. ISBN 0-8446-6702-1.

- ↑ See Greenfield's review of Milik "The Small Caves of Qumran" in Journal of the American Oriental Society Vol. 89, No. 1 (Jan.–Mar., 1969), pp. 128–141).

- ↑ British TV program: Channel 5, 21 April 2018, "The Dead Sea Treasure Map Mystery", 4/6

Works cited

- Adani, Samuel ben Joseph (1997). Sefer Naḥalat Yosef (in Hebrew). Ramat-Gan: Makhon Nir David. p. 17b (chapter4). OCLC 31818927. (reprinted from Jerusalem editions, 1907, 1917 and 1988)

- Allegro, John M. (1960). The Treasure of the Copper Scroll. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. OCLC 559692466.

- Allegro, John M. (1964). The Treasure of the Copper Scroll (2 ed.). Garden City, NY: Doubleday. OCLC 917557044.

- Ben-Yosef, Sefi (1979). "Dagon (Dok)". In Yitzhaki, Arieh (ed.). Israel Guide - The Judean Desert and The Jordan Valley (A useful encyclopedia for the knowledge of the country) (in Hebrew). Vol. 5. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, in affiliation with the Israel Ministry of Defence. pp. 54–55. OCLC 745203905.

- Brooke, George J.; Philip R. Davies, eds. (2002). Copper Scroll Studies. Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha Supplement Series, Vol. 40. New York: Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 0-8264-6055-0.

- Dalman, Gustaf (2020). Nadia Abdulhadi-Sukhtian (ed.). Work and Customs in Palestine, volume II. Vol. 2 (Agriculture). Translated by Robert Schick. Ramallah: Dar Al Nasher. ISBN 978-9950-385-84-9.

- Chapmann III, R.L.; Taylor, J.E., eds. (2003). Palestine in the Fourth Century A.D.: The Onomasticon by Eusebius of Caesarea. Translated by G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville. Jerusalem: Carta. ISBN 965-220-500-1. OCLC 937002750.

- Feather, Robert (2003). The Mystery of the Copper Scroll of Qumran: The Essene Record of the Treasure of Akhenaten. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781591438571.

- Gaster, Theodor (1976). The Dead Sea Scriptures (3rd ed.). New York: Anchor Books, Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385088596.

- García Martínez, Florentino; Tigchelaar, Eibert J. C., eds. (1999). The Dead Sea Scrolls: Study Edition, Vol.1 (2nd ed.). Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 9789004115477.

- Høgenhaven, Jesper (2015). "The Language of the Copper Scroll: A Renewed Examination". Revue de Qumrân. Peeters. 27 (2 (106)): 271–301. JSTOR 26566326.

- Lefkovits, Judah K. (1994). The Copper Scroll 3-Q15 a new reading, translation and commentary [Thesis (Ph.D.)--New York University, 1993] (in English and Hebrew). Ann Arbor, Mich: University Microfilms International (UMI). OCLC 233980235.

- Lefkovits, Judah K. (2000). The Copper Scroll 3Q15: A Reevaluation: A New Reading, Translation, and Commentary. Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah, Vol. 25. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-10685-5.

- Lurie, Benzion, ed. (1964). The Copper Scroll from the Judean Desert (megīllat ha-neḥoshet mimidbar yehūdah) (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: The Society for biblical research in Israel, in affiliation with Kiryat Sefer Publishing House. OCLC 233295816.

- Milik, J.T. (1960). "The Copper Document from Cave III of Qumran: Translation and Commentary". Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 4-5. Amman: Department of Antiquities (Jordan). pp. 147–148. OCLC 1063927215.

- Parry, Donald W. (2005). Tov, Emanuel (ed.). The Dead Sea Scrolls Reader, Vol. 6: Additional Genres and Unclassified Texts. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 250–261. ISBN 90-04-12646-5.

- Puech, Emile; Poffet, Jean-Michel; et al. (2006). Le rouleau de cuivre de la grotte 3 de Qumrân (3Q15): expertise, restoration, epigraphie (2 vol.). Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah, Vol. 55. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, École biblique et archéologique française de Jérusalem, EDF Foundation. ISBN 978-90-04-14030-1. Puech had access to the cleaned artifact and scans; Vol. 1, pp. 169–216 has his text, commentary and French and English translations.

- Shanks, Hershel, ed. (1992). Understanding the Dead Sea Scrolls. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-41448-7.

- Schiffman, Lawrence H.; VanderKam, James C., eds. (2000a). Encyclopedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513796-5.

- Schiffman, Lawrence H.; Tov, Emanuel; VanderKam, James C., eds. (2000b). The Dead Sea Scrolls Fifty Years After Their Discovery. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. ISBN 978-965-221-038-8.

- Wolters, Albert (1996). The Copper Scroll: Overview, Text and Translation. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9781850757931.

Further reading

- Brooke, George J.; Davies, Philip R., eds. (2004). "Copper Scroll Studies". Academic Paperbacks. London: T & T Clark. OCLC 746927982. (papers delivered at the 1996 Copper Scroll Symposium)

- Milik, J.T. (1956). "The Copper Document from Cave III, Qumran". The Biblical Archaeologist. 19 (3): 60–64. doi:10.2307/3209219. JSTOR 3209219. S2CID 165466511.

- Puech, Émile; Lacoudre, Noël; Mébarki, Farah; Grenache, Claude (2000). "The Mysteries of the "Copper Scroll"". Near Eastern Archaeology. The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The American Schools of Oriental Research. 63 (3): 152–153. doi:10.2307/3210763. JSTOR 3210763. S2CID 164103947. (Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls: Discoveries, Debates, the Scrolls and the Bible)