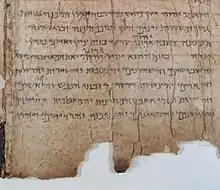

The Isaiah Scroll, designated 1QIsaa and also known as the Great Isaiah Scroll, is one of the seven Dead Sea Scrolls that were first discovered by Bedouin shepherds in 1946 from Qumran Cave 1.[1] The scroll is written in Hebrew and contains the entire Book of Isaiah from beginning to end, apart from a few small damaged portions.[2] It is the oldest complete copy of the Book of Isaiah, being approximately 1000 years older than the oldest Hebrew manuscripts known before the scrolls' discovery.[2] 1QIsaa is also notable in being the only scroll from the Qumran Caves to be preserved almost in its entirety.[3]

The scroll is written on 17 sheets of parchment. It is particularly large, being about 734 cm (24 feet) long and ranges from 25.3 to 27 cm high (10 to 10.6 inches) with 54 columns of text.[4]

History to discovery

.jpg.webp)

The exact authors of 1QIsaa are unknown, as is the exact date of writing. Pieces of the scroll have been dated using both radiocarbon dating and palaeographic/scribal dating. These methods resulted in calibrated date ranges between 356 and 103 BCE and 150–100 BCE respectively.[5][6] This seemingly fits with the theory that the scroll(s) was a product of the Essenes, a mystic Jewish sect, first mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History,[7] and later by Josephus[8] and Philo Judaeus.[9] Further supporting this theory are the number of Essene sectarian texts found in the surrounding Qumran Caves, and the lining up of recorded beliefs to artifacts or structures at the Qumran site (like communal meals and the obsession with ritual purity lining up with rooms with hundreds of plates and many ritual baths found at the site).[10] This theory is the most accepted in scholarly discourse. Further evidence that 1QIsaa was used by the sectarian community at Qumran is that scholars Abegg, Flint, and Ulrich argue that the same scribe who copied the sectarian scroll Rule of the Community (1QS) also made a correction to 1QIsaa.[11] The reason for the placement of 1QIsaa in Qumran Cave 1 is still unknown, though it has been speculated that it was placed, along with the other scrolls, by Jews (Essene or not) fleeing the Roman forces during the First Jewish–Roman War (c. 66–73 CE).[12]

The scroll was discovered in Qumran Cave 1, by a group of three Ta'amireh shepherds, near the Ein Feshkha spring off the northwest shore of the Dead Sea between late 1946 and early 1947; initially discovered when one of the shepherds heard the sound of shattering pottery after throwing a rock while searching for a lost member of his flock.[1] Once the shepherds agreed to return in a few days, the youngest one, Muhammed edh-Dhib returned alone before them, finding a cave filled with broken and whole jars and fragments of scrolls.[13] Of the intact jars, edh-Dhib found all but two empty; one was filled with reddish earth, and the other with a parchment scroll (later found to be the Great Isaiah Scroll) and two oblong items covered in a black wax or pitch (later found to be the Habakkuk Commentary (1QpHab) and the Community Rule (1QS)).[1] Edh-Dhib returned with the three scrolls to the displeasure of the other shepherds for his solo journey, and the scrolls were transferred to a Ta'amireh site southeast of Bethlehem where they were kept in a bag suspended on a tent pole for several weeks. During this time, the front cover of 1QIsaa broke off.[13] The three scrolls were brought to an antiques dealer in Bethlehem for appraisal.[14]

Publication

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

The scroll first came into the possession of Khalil Iskander Shahin, better known as Kando, an antiques dealer who was a member of the Syrian Church.[15] Kando was unable to make anything of the writing on the scroll, and sold it to Anastasius Yeshue Samuel (better known as Mar Samuel), the Syrian Archbishop of the Syrian Orthodox Church in East Jerusalem, who was anxious to have it authenticated.[16] The Archbishop consulted many scholars in Jerusalem to determine the nature and significance of the documents, and in July 1947, he finally consulted the École Biblique and came in contact with the visiting Dutch scholar Professor J. van der Ploeg of Nijmegen University. Van der Ploeg identified one of the manuscripts at the monastery as a copy of the Book of Isaiah in Hebrew, but was met with skepticism, as a fellow scholar at the École Biblique believed that the scrolls must be fakes due to their antiquity.[16]

In January 1948, Professor Eleazar Sukenik of the Chair of Palestinian Archaeology in the Hebrew University arranged to meet with a member of the Syrian community in the Y.M.C.A building of Jerusalem to see the scrolls and borrow them for a few days, after hearing of their existence at the monastery.[16] Upon realizing their authenticity, Sukenik copied several chapters of the Book of Isaiah from the manuscript and distributed copies to the Constituent Assembly of the State of Israel.[16]

On 18 February 1948, Father Butrus Sowmy of St. Mark's Monastery called the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) to contact William Brownlee, a Fellow at the ASOR, about publishing the Great Isaiah Scroll, the Habakkuk Commentary, and the Community Rule. Brownlee was away from the school temporarily, so Sowmy was put in contact with Dr. John Trever, photographer and temporary director of the school.[17] Trever photographed the scrolls and sent the photographs to palaeographer and dean of American archaeologists, Professor William Albright of Johns Hopkins University, who dated the manuscript of Isaiah at around 100 BCE.[17]

Early in 1949, Mar Samuel, Syrian Archbishop–Metropolitan of Jerusalem, brought the scroll to the United States, hoping to sell it and the three others he had in his possession.[16] Samuel permitted ASOR to publish them within a limit of three years, and so Dr. Millar Burrows, director of ASOR, along with Dr. John Trever and Dr. William Brownlee prepared the scrolls for publication.[16] The scrolls initially purchased by Samuel were published by the American Schools of Oriental Research in 1950, and included 1QIsaa, 1QpHab, and 1QS.[17] The scrolls were advertised for sale in the Wall Street Journal in June, 1954 under the "miscellaneous" columns, but were eventually bought by Israeli archeologist Yigael Yadin for $250,000 in 1954 and brought back to Israel, although the purchase was not announced until February 1955.[15] The scroll, along with over 200 fragments from the Dead Sea Scrolls, is now housed in Jerusalem at the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum. Recently, the Israel Museum, in a partnership with Google, created the Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Project, and has digitized 1QIsaa, the Great Isaiah Scroll, providing a high-quality image of the entire scroll. The digitized scroll provides an English translation alongside the original text,[18] and can be viewed here.

Scribal profile and textual variants

The text of the Great Isaiah Scroll is generally consistent with the Masoretic version and preserves all sixty-six chapters of the Hebrew version in the same sequence.[2] There are small areas of damage where the leather has cracked off and a few words are missing.[4] The text displays a scribal hand typical of the period of 125–100 BCE.[4] The scroll also displays a tendency towards longer spellings of words which is consistent with this period.[4] There is evidence of corrections and insertions by later scribes between the date of original writing and 68 CE.[4] A unique feature of the scroll is that it is divided into two halves, each with 27 columns and 33 chapters, unlike later versions, suggesting that this may be the earliest dividing point for the book of Isaiah.[3] There is some debate among scholars over whether the entire original scroll was copied by a single scribe, or by two scribes mirroring each other's writing styles. A 2021 analysis by researchers at the University of Groningen applied artificial intelligence and pattern recognition tools to determine that it was highly likely that two scribes copied the scroll, each contributing one of the two halves.[19][20]

The scroll contains scribal errors, corrections, and more than 2600 textual variants when compared with the Masoretic codex.[2] This level of variation in 1QIsaa is much greater than other Isaiah scrolls found at Qumran, with most, such as 1QIsab, being closer to the Masoretic Text.[3] Some variants are significant and include differences in one or more verses or in several words. Most variants are more minor and include differences of a single word, alternative spellings, plural versus single usage, and changes in the order of words.[11]

Some of the major variants are notable as they show the development of the book of Isaiah over time or represent scribal errors unique to 1QIsaa. Abegg, Flint and Ulrich argue that the absence of the second half of verse 9 and all of verse 10 in chapter 2 of 1QIsaa indicates that these are slightly later additions.[11] These verses are found in other Qumran Isaiah scrolls, the Masoretic Text, and the Septuagint.[11] In chapter 40, a shorter version of verse 7 is found, matching the Septuagint. In the same verse there is also an insertion by a later scribe showing a longer version that is consistent with the Masoretic Text.[3] There are also several examples of likely scribal error in the scroll, such as Isaiah 16:8–9. Most of 16:8 is missing and the first part of verse 9 is missing when compared to the Masoretic Text and Septuagint, suggesting that the scribe's eye may have skipped over part of the text.[11] Abegg, Flint, and Ulrich note that there are a number of errors of this nature that may represent a degree of carelessness on the part of the scribe.[11]

In some cases, the variants from 1QIsaa have been incorporated in modern bible translations. An example is Isaiah 53:11 where 1QIsaa and Septuagint versions match and clarify the meaning, while the Masoretic Text is somewhat obscure.[3] Dr. Peter Flint notes that better readings from the Qumran scrolls such as Isaiah 53:11 have been adopted by the New International Version translation and Revised Standard Version translation.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Ulrich, Eugene; Flint, Peter W.; Abegg, Jr., Martin G. (2010). Qumran Cave 1: II: The Isaiah Scrolls. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-19-956667-9.

- 1 2 3 4 The Digital Dead Sea Scrolls: The Great Isaiah Scroll dss.collections.imj.org

- 1 2 3 4 5 Flint, Peter W. (2013). The Dead Sea Scrolls. Nashville: Abingdon Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-0-687-49449-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ulrich, Eugene; Flint, Peter W.; Abegg, Jr., Martin G. (2010). Qumran Cave 1: II : the Isaiah scrolls. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 59–65, 88. ISBN 978-0-19-956667-9.

- ↑ dead-sea-scrolls-2 Allaboutarchaeology.org

- ↑ Jull, Timothy A. J.; Donahue, Douglas J.; Broshi, Magen; Tov, Emanuel (1995). "Radiocarbon Dating of Scrolls and Linen Fragments from the Judean Desert". Radiocarbon. 37 (1): 14. Bibcode:1995Radcb..37...11J. doi:10.1017/S0033822200014740. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder. Historia Naturalis. V, 17 or 29; in other editions V, (15).73. "Ab occidente litora Esseni fugiunt usque qua nocent, gens sola et in toto orbe praeter ceteras mira, sine ulla femina, omni venere abdicata, sine pecunia, socia palmarum. in diem ex aequo convenarum turba renascitur, large frequentantibus quos vita fessos ad mores eorum fortuna fluctibus agit. ita per saeculorum milia — incredibile dictu — gens aeterna est, in qua nemo nascitur. tam fecunda illis aliorum vitae paenitentia est! infra hos Engada oppidum fuit, secundum ab Hierosolymis fertilitate palmetorumque nemoribus, nunc alterum bustum. inde Masada castellum in rupe, et ipsum haut procul Asphaltite. et hactenus Iudaea est." cf. English Translation"

- ↑ Josephus. (c.75 CE). The Wars of the Jews 2.119

- ↑ Philo. Quad Omnis Probus Liber. XII.

- ↑ Flint, Peter W. (2013). The Dead Sea Scrolls. Nashville: Abingdon Press. pp. 137–151.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Abegg, Martin G.; Flint, Peter; Ulrich, Eugene (1999). The Dead Sea scrolls Bible : the oldest known Bible, translated for the first time into English. Abegg, Martin G., Jr.; Flint, Peter W.; Ulrich, Eugene (1st ed.). San Francisco, California. pp. 214, 268–270. ISBN 9780060600648. OCLC 41076443.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Writing the Dead Sea Scrolls". July 2010. National Geographic Channel. TV Movie, approx. 39:00–.

- 1 2 Flint, Peter W. "The Dead Sea Scrolls". Abingdon Press, Nashville, 2013, p. 2

- ↑ "The Dead Sea Scrolls – Discovery and Publication". www.deadseascrolls.org.il. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- 1 2 Cross, Frank Moore (1995). The Ancient Library of Qumran (3rd ed.). Minneapolis: Fortress Press. pp. 20–24. ISBN 0-8006-2807-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bruce, F. F. (1964). Second Thoughts on the Dead Sea Scrolls. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 13–19.

- 1 2 3 LaSor, William Sanford (1956). Amazing Dead Sea Scrolls. Chicago: Moody Press. pp. 13–19.

- ↑ "Digital Dead Sea Scrolls at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem – The Project". dss.collections.imj.org.il. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- ↑ Ouellette, Jennifer (21 April 2021). "More than one scribe wrote the text of a Dead Sea Scroll, handwriting shows". Ars Technica. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ↑ Popović, Mladen; Dhali, Maruf A.; Schomaker, Lambert (2021). "Artificial intelligence based writer identification generates new evidence for the unknown scribes of the Dead Sea Scrolls exemplified by the Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa)". PLOS One. 16 (4): e0249769. arXiv:2010.14476. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1649769P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0249769. PMC 8059865. PMID 33882053.