| Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities | |

|---|---|

| Autonomous region of Mexico | |

| 1994–2023 | |

Flag

| |

Territory fully or partially controlled by the Zapatistas in Chiapas | |

| Anthem | |

| Himno Zapatista | |

| Capital | None (de jure) Oventik (Tiamnal, Larráinzar) (de facto)[1] |

| Area | |

| • Coordinates | 16°55′33″N 92°45′37″W / 16.92583°N 92.76028°W |

• 2018 | 24,403 km2 (9,422 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2018 | 300,000[2][3] |

| Status | Former de facto autonomous region of Chiapas |

| Government | Councils of Good Government |

| • Type | Municipal council |

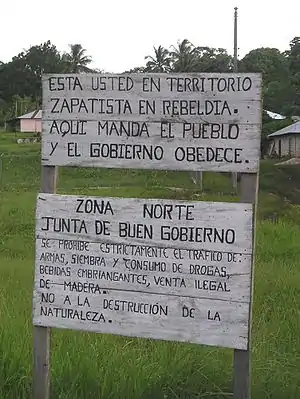

| • Motto | Aquí manda el Pueblo y el Gobierno Obedece (Spanish) "Here the people rule and the government obeys" |

| History | |

| 1 January 1994 | |

• Caracoles established[4] | 9 August 2003 |

• Sixth Declaration of the Selva Lacandona[5] | 30 June 2005 |

• Dissolution and restructuring[6] | 5 November 2023 |

The Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities (Spanish: Municipios Autónomos Rebeldes Zapatistas, MAREZ) were the de facto autonomous territories controlled by the neo-Zapatista support bases in the Mexican state of Chiapas. They were founded following the Zapatista uprising which took place in 1994[7] and were part of the wider Chiapas conflict. Despite attempts at negotiation with the Mexican government which resulted in the San Andrés Accords in 1996, the region's autonomy remained unrecognized by that government.[8]

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) did not hold formal political power in the autonomous municipalities. According to its constitution, no commander or member of the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee may take positions of authority or government in these spaces.[9]

These places were found within the official municipalities, and several were even within the same municipality, as in the case of San Andrés Larráinzar and Ocosingo. The MAREZ were coordinated by autonomous Zapatista Councils of Good Government (Spanish: Juntas de Buen Gobierno) and their main objectives were to promote education and health in their territories. They also fought for land rights, labor and trade, housing, and fuel-supply issues, promoting arts (especially indigenous language and traditions), and administering justice.[10]

On 17 August 2019, the Zapatistas announced a significant increase of autonomous municipalities, and a new term for centers of Zapatista autonomy. In most cases these Centers of Autonomous Resistance and Zapatista Rebellion (Spanish: Centros de Resistencia Autónoma y Rebeldía Zapatista, CRAREZ) include a Caracol (English: "Snail"), a Council of Good Government, and a Rebel Autonomous Zapatista Municipality (MAREZ). The Zapatistas credited this growth primarily to the efforts of "women, men, children, and elders of the Zapatista bases of support" and secondarily to a backfiring counter-insurgency strategy of the Mexican state, which "generate[s] conflict and demoralization" among non-Zapatistas.[11] Eleven new Centers of Autonomous Resistance and Zapatista Rebellion (CRAREZ) were declared; specifically, four new autonomous municipalities and seven new Caracoles (each accompanied by a Council of Good Government). This raised the total number of Caracoles from five to twelve, and brought the total number of autonomous Zapatistas centers to 43, including 27 original autonomous Zapatista municipalities, 5 original Caracoles, and the 11 autonomous Zapatista centers newly declared.[11]

In November 2023, after increased cartel violence, the EZLN announced the dissolution of the MAREZ, with only the Caracoles remaining open to locals. Later that month, they announced the reorganisation of the MAREZ into thousands of "Local Autonomous Governments" (GAL) which form area-wide "Zapatista Autonomous Government Collectives" (CGAZ) and zone-wide "Assemblies of Collectives of Zapatista Autonomous Governments" (ACGAZ).[12]

Background

On 1 January 1994, thousands of EZLN members occupied towns and cities in Chiapas, burning down police stations, occupying government buildings, and skirmishing with the Mexican army. The EZLN demanded "work, land, housing, food, health care, education, independence, freedom, democracy, justice, and peace" in their communities.[13] The Zapatistas seized over a million acres from large landowners during their revolution.[14]

Distribution

Since 2003, the Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities (MAREZ) coordinated in very small groups called caracoles (English: "snails" or "seashells"). Before that, the Neo-Zapatistas used the title of Aguascalientes after the site of the EZLN-organized National Democratic Convention on 8 August 1994;[15] this name alluded to the Convention of Aguascalientes during the Mexican Revolution where Emiliano Zapata and other leaders met in 1914 and Zapata made an alliance with Francisco Villa.

| MAREZ | Caracol | Former Name (Aguascalientes) | Indigenous Groups | Area and municipalities in which they were found |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mother of the sea snails of our dreams | La Realidad | Tojolabales, Tzeltales, and Mames | Selva Fronteriza. "Ocosingo, Marques de Comillas" |

|

Whirlwind of our words | Morelia | Tzeltales, Tzotziles, and Tojolabales | Tzots Choj Altamirano, Comitán |

|

Resistance toward a new dawn | La Garrucha | Tzeltales | Selva Tzeltal "Ocosingo, Altamirano" |

|

That speaks for all | Roberto Barrios | Choles, Zoques, and Tzeltales | Zona Norte de Chiapas San Andrés Larrainzar, El Bosque, Simojovel de allende |

|

Resistance and rebellion for humanity | Oventic | Tzotziles, and Tzeltales | Altos de Chiapas, San Andrés Larrainzar, Teopisca. |

| Hope of Humanity | Ejido Santa María | Chicomuselo | ||

| Ernesto Che Guevara | El Belén | Motozintla | ||

| Planting consciousness in order to harvest revolutions for life | Tulan Ka’u | Amatenango del Valle | ||

| December 21 | K’anal Hulub | Chilón | ||

| CRAREZ | Caracol | Former Name (Aguascalientes) | Area and municipalities in which they were found |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steps of History, for the life of Humanity | The heart of rebellious seeds collective, memory of Comrade Galeano | La Unión | San Quintín |

| Seed that flourishes with the conscience of those who struggle forever | Dignified spiral weaving the colors of humanity in memory of the fallen ones | ||

| New Dawn in resistance and rebellion for life and humanity | Flourishing the rebellious seed | El Poblado Patria Nueva | Ocosingo |

| The rebellious thinking of the original peoples | In honor of the memory of Comrade Manuel | Dolores Hidalgo | Ocosingo |

| The light that shines on the world | Resistance and rebellion, a new horizon | El Poblado Nuevo Jerusalén | Ocosingo |

| Heart of our lives for the new future | Root of the resistances and the rebellions for humanity | Ejido Jolj’a | Tila |

| Flower of our word and light of our people that reflects for all | Jacinto Canek | Comunidad del CIDECI-Unitierra | San Cristóbal de las Casas |

Government

At a local level, people attended a popular assembly of around 300 families in which anyone over the age of twelve could participate in decision-making. These assemblies strove to reach a consensus, but were willing to fall back to a majority vote. The communities formed a federation with other communities to create an autonomous municipality, which formed further federations with other municipalities to create a region.[18]

Each community had three main administrative structures: (1) the commissariat, in charge of day-to-day administration; (2) the council for land control, which dealt with forestry and disputes with neighboring communities; and (3) the agencia, a community police agency.[19]

Public services

Education

The Zapatistas ran hundreds of schools with thousands of teachers. They were modeled around the principles of democratic education in which students and communities collectively decide on school curriculum and students weren't graded.[20]

Healthcare

The Zapatistas maintained a universal healthcare service which was provided free of charge. However, patients still had to pay for medications to cover restocking costs.[21] Residents of Zapatista communities believed their health services were better staffed and equipped, and less racist towards indigenous people than most services in Chiapas. The healthcare service of the Zapatistas worked with surrounding hospitals and freely took in patients from other communities who needed to use the medical facilities that only the Zapatistas had.[22] Since 1994, the Zapatistas built two new hospitals and 18 health clinics in the region.[20] One 2014 study indicated the following achievements in Zapatista healthcare:

- In 2005, 84.2% of Zapatista children were fully vaccinated, while that figure stood at 74.8% in pro-government communities.[23]

- In regions where there were previously significantly high rates of death during childbirth, there has now been a period of eight years or more where no maternal deaths have been recorded.

- The manufacture and consumption of alcohol has been banned, which is directly linked to the reduction in many illnesses and infections including ulcers, cirrhosis, malnutrition, and surgical wounds.[24] Banning the consumption of alcohol was a collective decision. Nayely, a Zapatista representative, stated that alcohol is “not good for one’s health, and just wastes money”.[25]

According to one account of Oventic from 2016:

In Oventic, there was a small yet seemingly fully-functional medical clinic, which appeared to offer basic healthcare. A sign on the door said general consultations, gynecology, optometry and laboratory services were all available five days a week. Emergency services were available 24 hours, seven days a week. They appeared to have a shiny new ambulance at their disposal. Other services offered a few days a week included dentistry and ultrasounds.[26]

Water

Many Zapatista communities were in rural areas with little access to running water. Projects were undertaken to supply Zapatista communities with fresh water. In one case, Roberto Arenas, a small Tzeltal community, built its own water service with the help of solidarity activists. Such projects were coordinated democratically. An account by Ramor Ryan noted:[27]: 10

The good government committee of the autonomous municipality refer the case to their elected water commission and the options are weighed. The commission consults various parties including the local EZLN commander and clandestine committee members, and so, in the end, after the issue has been bandied around what seems like half the inhabitants of this particular region of the jungle, the community of Roberto Arenas is notified about the eligibility of their request. It’s a process similar to what happens anywhere in the world at a local council level, except for one significant difference: the state authorities have no involvement whatsoever; this is an autonomous process overseen by the communities’ people. There is no separation between who is governed and who is governing—they are one and the same.

Ryan described the process of finishing the water project:[27]: 179

We’re getting lots of little bits and pieces done, fine tuning this and that. Helping people construct their family tap stands, digging here and there, testing the pressure, tightening valves. A group of women come together during the morning to put together a tap stand for the collective clothes washing area. We earmark a bag of cement—the very last one—for the later construction of a large concrete washbasin. The day is punctuated by minor moments of crisis—people coming up and saying that the water isn’t arriving to their house—but it is usually just a blocked pipe or a faulty connection. Really, the system is almost flawless and works perfectly fine; it’s been an exemplary project.

Environmental protection

The Zapatistas took on many projects to protect and restore the damaged ecosystems of the Lacandon Jungle, including the banning of chemical fertilisers and pesticides, as well as resisting the extraction of oil and metal through mining.[28] According to one person who stayed in the town of Oventic in 2016:

There was also something else — something which took me a long time to put my finger on. Then it finally hit me: there was no litter; not even a stray chocolate bar wrapper.[26]

The Zapatistas also embarked on beekeeping and reforestation efforts, including planting over 30,000 trees in order to protect water sources (especially important given the increasing water scarcity in Chiapas),[29] reverse deforestation in the rainforests and provide sources of food, fuel and construction material.[30] Beekeepers aimed to reverse much of the collapse of the bee population and produce honey, for food, ecological regeneration, and candles.[31] American eco-socialist scholar Joel Kovel praised the efforts of the Zapatistas to construct an ecological society.[32]

Dissolution

In early November 2023, a communique signed by Subcomandante Moises announced the dissolution of the Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities,[6][33][34][35] along with their Councils of Good Government.[33][34][35] The announcement declared that, effective immediately, all positions and documents related to the MAREZ would be considered invalid.[34] The statement clarified that the Caracoles (Zapatista community centres) would continue providing their services to locals, but would be "closed to outsiders".[6][33][34][35]

Although he did not specify reasons for the dissolution, Moises cited rising cartel violence along the Guatemala–Mexico border, where many of its municipalities are located.[6][33][34] The state of Chiapas had already been experiencing a rise in people smuggling, drug trafficking and open conflict between the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel.[6][34] In September 2021, the EZLN had described the situation in the state as a "civil war".[35] The Zapatistas reported that the cartels, which they linked with the Mexican government, had carried out "road blockades, robberies, kidnappings, extortion, forced recruitment, [and] shootouts" in the region.[6][33][34][35] The statement described the cities of Chiapas as being in "complete chaos",[33][34][35] and that many (including San Cristóbal de las Casas, Comitán, Las Margaritas and Palenque) were controlled by the cartels.[33][34] They also reported that the Mexican Army and National Guard, which had deployed thousands of troops to the region, had not combatted criminal violence; they claimed that the Mexican state's troops were only there to prevent illegal immigration to the United States.[6][33][34][35]

According to the statement, the decision to dissolve the MAREZ had been discussed for months prior to the announcement.[33][34] It has been speculated that the decision had been taken due to the upcoming 2024 Mexican general election. According to Mexican anthropologist Gaspar Morquecho, the Zapatistas had also become "increasingly isolated", cutting ties with other organisations. Morquecho claimed this had caused many in the younger generation to leave the Zapatista municipalities, in order to seek work or education.[6]

Moises promised that future statements would clarify the reasons for the decision, as well as details on the restructuring of "Zapatista autonomy". The statement also stated the Zapatistas' intention to celebrate the 30th anniversary of their uprising, inviting people to come, while also warning that Chiapas was no longer safe.[6][33]

See also

References

- ↑ "Caracoles y Juntas de Buen Gobierno". Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Vidal, John (17 February 2018). "Mexico's Zapatista rebels, 24 years on and defiant in mountain strongholds". The Guardian. ISSN 1756-3224. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ↑ Innes, Erin (17 February 2018). ""We don't need permission to be free": Women Zapatistas and the "modernization" of NAFTA". Briarpatch. ISSN 0703-8968. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ↑ Gonzlez Casanova, Pablo (11 September 2003). "Los caracoles zapatistas: Redes de resistencia y autonoma". La Jornada (in Spanish). Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ↑ "Sixth Declaration of the Selva Lacandona". Enlace Zapatista. 30 June 2005. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Clemente, Édgar H. (6 November 2023). "Mexico's Zapatista rebel movement says it is dissolving its 'autonomous municipalities'". Associated Press. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ↑ Reyes Godelmann, Iker (30 July 2014). "The Zapatista Movement: The Fight for Indigenous Rights in Mexico". Australian Institute of International Affairs. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ↑ Villegas, Paulina (26 August 2017). "In a Mexico 'Tired of Violence,' Zapatista Rebels Venture Into Politics". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Gloria Muñóz Ramírez (2003). 20 y 10 el fuego y la palabra. Revista Rebeldía y Demos, Desarrollo de Medios, S.A. de C.V. La Jornada Ediciones.

- ↑ Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos (July 2003). "Chiapas: La treceava estela". Cartas y comunicados del EZLN.

- 1 2 Moisés, Subcomandante Insurgente (17 August 2019). "Communique from the EZLN's CCRI-CG And, We Broke the Siege". Enlace Zapatista. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ↑ "Novena Parte: La Nueva Estructura de la Autonomía Zapatista". Enlace Zapatista (in Spanish). 13 November 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ↑ Muñóz Ramírez, Gloria (2008). The Fire and the Word: A History of the Zapatista Movement. Translated by Carlsen, Laura; Reyes Arias, Alejandro. City Lights. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-87286-488-7. LCCN 2007052477.

- ↑ Grubačić, Andrej; O'Hearn, Denis (2016). "Zapatistas". Living at the Edges of Capitalism: Adventures in Exile and Mutual Aid. University of California Press. p. 129. ISBN 9780520287303. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctv1xxx8z. LCCN 2015036704.

- ↑ "Los Aguascalientes: Centros Culturales en el Corazón de la Selva Lacandona y en las montañas y rincones zapatistas". itzcuintli rebelde. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- 1 2 Hidalgo, Onésimo; Castro Soto, Gustavo (2003). "Cambios en el EZLN". Chiapas al Día. Boletín de CIEPAC. San Cristóbal de las Casas.

- 1 2 Oikonomakis, Leonidas (19 August 2019). "Zapatistas announce major expansion of autonomous territories". ROAR Magazine. ISSN 2468-1695. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ↑ Flood, Andrew (1999). "The Zapatistas, anarchism and 'Direct democracy'". Anarcho-Syndicalist Review. No. 27. ISSN 1069-1995.

- ↑ Barmeyer, Niels (2009). "Who is Running the Show? The Workings of Zapatista Government". Developing Zapatista Autonomy: Conflict and NGO Involvement in Rebel Chiapas. University of New Mexico Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-8263-4584-4. LCCN 2008045276.

- 1 2 Zibechi, Raúl (2012). Territories in Resistance: A Cartography of Latin American Social Movements. AK Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-84935-107-2. LCCN 2012937110.

- ↑ Cuevas, J.H. (March 2007). "Health and Autonomy: the case of Chiapas" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2021.

- ↑ Resistencia Autónoma: Cuaderno de texto de primer grado del curso de "La Libertad según l@s Zapatistas. p. 19.

- ↑ Castellanos, Laura (4 January 2014). "El suicidio ronda en San Andrés". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ↑ Warfield, Cian (October 2014). Understanding Zapatista Autonomy: An Analysis of Healthcare and Education.

- ↑ Contreras Baspineiro, Alex (8 May 2004). "The Zapatistas Reject the War on Drugs". Narco News. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- 1 2 Mallett-Outtrim, Ryan (13 August 2016). "Two decades on: A glimpse inside the Zapatista's capital, Oventic". Links: International Journal of Socialist Renewal. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- 1 2 Ryan, Ramor (2011). Zapatista Spring: Anatomy of a Rebel Water Project & the Lessons of International Solidarity. AK Press. ISBN 978-1-84935-072-3. LCCN 2011925323.

- ↑ Gobierno Autónomo I: Cuaderno de texto de primer grado del curso de "La Libertad según l@s Zapatistas". p. 19.

- ↑ ""Development" and Extraction: Water Scarcity in Chiapas". Schools for Chiapas. 9 July 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ↑ "Neem: The People's Pharmacy". Schools for Chiapas. 20 February 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ↑ "The Other Bee: Reviving a Mayan Tradition". Schools for Chiapas. 19 February 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ↑ Kovel, Joel (2007) [2002]. Enemy of Nature: The End of Capitalism or the End of the World?. Zed Books. pp. 252–253. ISBN 978-1-84277-870-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Henríquez, Elio (5 November 2023). "Anuncia EZLN desaparición de sus municipios autónomos". La Jornada (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Flores, Miguel (7 November 2023). "Así fue como el EZLN perdió el control de municipios autónomos en Chiapas frente al CJNG y el Cártel de Sinaloa". Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ferri, Pablo (6 November 2023). "El EZLN anuncia la desaparición de su estructura civil: "Las ciudades de Chiapas están en caos"". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 November 2023.

Bibliography

Books

- Barmeyer, Niels (2009). "Who is Running the Show? The Workings of Zapatista Government". Developing Zapatista Autonomy: Conflict and NGO Involvement in Rebel Chiapas. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-4584-4. LCCN 2008045276.

- Cerullo, Margaret (2009). "The Zapatistas Other Politics: The Subjects Of Autonomy". In Fasenfest, David (ed.). Engaging Social Justice: Critical Studies of 21st Century Social Transformation. Studies in Critical Social Sciences. Vol. 13. Brill Publishers. pp. 289–299. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004176546.i-350.94. ISBN 978-90-04-17654-6.

- Chabot, Sean; Vinthagen, Stellan (2020). "One no against violence, many yeses beyond violence: Zapatista dignity, autonomy, counter-conduct". In Jackson, Richard; Llewellyn, Joseph; Manawaroa Leonard, Griffin; Gnoth, Aidan; Karena, Tong (eds.). Revolutionary Nonviolence: Concepts, Cases and Controversies. Zed Books. pp. 107–131. ISBN 978-1-78699-825-5.

- Eldredge Fitzwater, Dylan (2019). Autonomy Is in Our Hearts: Zapatista Autonomous Government through the Lens of the Tsotsil Language. PM Press. ISBN 978-1-62963-580-4. LCCN 2018931534.

- Grubačić, Andrej; O'Hearn, Denis (2016). "Zapatistas". Living at the Edges of Capitalism: Adventures in Exile and Mutual Aid. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520287303. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctv1xxx8z. LCCN 2015036704.

- Halkin, Alexandra (2008). "Outside the Indigenous Lens: Zapatistas and Autonomous Videomaking". In Wilson, Pamela; Stewart, Michelle (eds.). Global Indigenous Media: Cultures, Poetics, and Politics. Duke University Press. pp. 160–180. ISBN 9780822388692.

- Kovel, Joel (2007) [2002]. "Ecosocialism". Enemy of Nature: The End of Capitalism or the End of the World?. Zed Books. pp. 242–275. ISBN 978-1-84277-870-8.

- Muñóz Ramírez, Gloria (2008). The Fire and the Word: A History of the Zapatista Movement. Translated by Carlsen, Laura; Reyes Arias, Alejandro. City Lights. ISBN 978-0-87286-488-7. LCCN 2007052477.

- Ryan, Ramor (2011). Zapatista Spring: Anatomy of a Rebel Water Project & the Lessons of International Solidarity. AK Press. ISBN 978-1-84935-072-3. LCCN 2011925323.

- Speed, Shannon (2014). "Zapatista Autonomy, Local Governance, and an Organic Theory of Rights". In Warrior, Robert (ed.). The World of Indigenous North America. Routledge. pp. 82–102. ISBN 978-0-415-87952-1. LCCN 2013039796.

- Stahler-Sholk, Richard (2014). "Mexico: Autonomy, Collective Identity, and the Zapatista Social Movement". In Stahler-Sholk, Richard; Vanden, Harry E.; Becker, Marc (eds.). Rethinking Latin American Social Movements: Radical Action from Below. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 187–207. ISBN 978-1-4422-3567-0. LCCN 2014030142.

- Zibechi, Raúl (2012). Territories in Resistance: A Cartography of Latin American Social Movements. AK Press. ISBN 978-1-84935-107-2. LCCN 2012937110.

Journal articles

- Chatterton, Paul; Ryan, Ramor (2008). "¡Ya Basta! The Zapatista struggle for autonomy revisited". City. 12 (1): 115–125. doi:10.1080/13604810801933800. ISSN 1360-4813.

- Cortez Ruiz, Carlos (2004). "Social Strategies and Public Policies in an Indigenous Zone in Chiapas, Mexico" (PDF). IDS Bulletin. 35 (2): 76–83. ISSN 0265-5012.

- Dinerstein, Ana Cecilia (2013). "The Speed of the Snail: The Zapatistas' Autonomy De Facto and the Mexican State". Bath Papers in International Development and Wellbeing (20): 1–17. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2401859. ISSN 2040-3151.

- Earle, Duncan; Simonelli, Jeanne (2004). "The Zapatistas and Global Civil Society: Renegotiating the Relationship". European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies (76): 119–125. ISSN 0924-0608. JSTOR 25676076.

- Forbis, Melissa M. (2016). "After autonomy: the zapatistas, insurgent indigeneity, and decolonization". Settler Colonial Studies. 6 (4): 365–384. doi:10.1080/2201473X.2015.1090531. ISSN 2201-473X.

- Fox, Jonathan (2007). "Rural democratization and decentralization at the state/society interface: What counts as 'local' government in the mexican countryside?". The Journal of Peasant Studies. 34 (3–4): 527–559. doi:10.1080/03066150701802934. ISSN 0306-6150.

- Maldonado-Villalpando, Erandi; Paneque-Gálvez, Jaime; Demaria, Federico; Napoletano, Brian M. (2022). "Grassroots innovation for the pluriverse: evidence from Zapatismo and autonomous Zapatista education". Sustainability Science. 17 (4): 1301–1316. doi:10.1007/s11625-022-01172-5. ISSN 1862-4065. PMC 9261257.

- González Casanova, Pablo (2005). "The Zapatista "caracoles": Networks of resistance and autonomy". Socialism and Democracy. 19 (3): 79–92. doi:10.1080/08854300500257963. ISSN 0885-4300.

- Guillén, Diana (2017). "Societies in Movement vs. Institutional Continuities? Insights from the Zapatista Experience". Latin American Perspectives. 44 (4): 114–138. doi:10.1177/0094582X16635292. ISSN 0094-582X.

- Harvey, Neil (2005). "Inclusion Through Autonomy: Zapatistas and Dissent". NACLA Report on the Americas. 39 (2): 12–17. doi:10.1080/10714839.2005.11722353. ISSN 1071-4839.

- Harvey, Neil (2016). "Practicing autonomy: Zapatismo and decolonial liberation". Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies. 11 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1080/17442222.2015.1094872. ISSN 1744-2222.

- Mora, Mariana (2003). "The Imagination to Listen: Reflections on a Decade of Zapatista Struggle". Social Justice. 30 (3): 17–31. ISSN 1043-1578. JSTOR 29768206.

- Mora, Mariana (2007). "Zapatista Anticapitalist Politics and the "Other Campaign": Learning from the Struggle for Indigenous Rights and Autonomy". Latin American Perspectives. 34 (2): 64–77. doi:10.1177/0094582X06299086. ISSN 0094-582X.

- Mora, Mariana (2015). "The Politics of Justice: Zapatista Autonomy at the Margins of the Neoliberal Mexican State". Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies. 10 (1): 87–106. doi:10.1080/17442222.2015.1034439. ISSN 1744-2222.

- Reyes, Alvaro; Kaufman, Mara (2011). "Sovereignty, Indigeneity, Territory: Zapatista Autonomy and the New Practices of Decolonization". South Atlantic Quarterly. 110 (2): 505–525. doi:10.1215/00382876-1162561. hdl:10161/10650. ISSN 0038-2876.

- Stahler-Sholk, Richard (2007). "Resisting Neoliberal Homogenization: The Zapatista Autonomy Movement". Latin American Perspectives. 34 (2): 48–63. doi:10.1177/0094582X06298747. ISSN 0094-582X. JSTOR 27648009.

- Stahler-Sholk, Richard (2010). "The Zapatista Social Movement: Innovation and Sustainability". Alternatives: Global, Local, Political. 35 (3): 269–290. doi:10.1177/030437541003500306. ISSN 0304-3754.

- van der Haar, Gemma (2004). "The Zapatista Uprising and the Struggle for Indigenous Autonomy". European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies (76): 99–108. ISSN 0924-0608. JSTOR 25676074.

- Zugman, Kara (2005). "Autonomy in a Poetic Voice: Zapatistas and Political Organizing in Los Angeles". Latino Studies. 3 (3): 325–346. doi:10.1057/palgrave.lst.8600157. ISSN 1476-3435.