Relationships (Outline) |

|---|

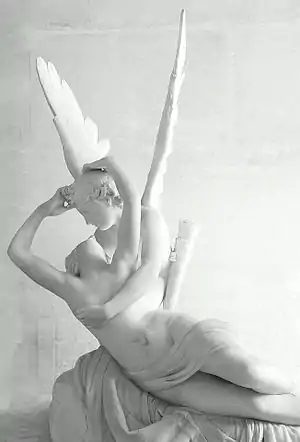

| Part of a series on |

| Love |

|---|

Red-outline heart icon |

Limerence is a state of mind which results from romantic or non-romantic feelings for another person, and typically includes intrusive, melancholic thoughts, or tragic concerns for the object of one's affection as well as a desire to form or maintain a relationship with the object of love and to have one's feelings reciprocated. Limerence can also be defined as an involuntary state of intense desire for someone, marked by intrusive thoughts and a desire for a relationship and reciprocation.

Psychologist Dorothy Tennov coined the term "limerence" for her 1979 book, Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love, to describe a concept that had grown out of her work in the mid-1960s, when she interviewed over 500 people on the topic of love.[1]

Limerence, which is not exclusively sexual, has been defined in terms of its potentially inspirational effects and relation to attachment theory. It has been described as being "an involuntary potentially inspiring state of adoration and attachment to a limerent object (LO) involving intrusive and obsessive thoughts, feelings and behaviors from euphoria to despair, contingent on perceived emotional reciprocation".[2] Willmott and Bentley remark that limerence has received little attention in the scientific literature.[3]

Attachment theory emphasizes that "many of the most intense emotions arise during the formation, the maintenance, the disruption, and the renewal of attachment relationships".[4] It has been suggested that "the state of limerence is the conscious experience of sexual incentive motivation" during attachment formation, "a kind of subjective experience of sexual incentive motivation"[5] during the "intensive ... pair-forming stage"[6] of human affectionate bonding.

Characteristics

The concept of limerence "provides a particular carving up of the semantic domain of love",[7] and represents an attempt at a scientific study of the nature of love. Limerence is considered as a cognitive and emotional state of being emotionally attached to or even obsessed with another person, and is typically experienced involuntarily and characterized by a strong desire for reciprocation of one's feelings—a near-obsessive form of romantic love.[8] For Tennov, "sexual attraction is an essential component of limerence ... LO, in order to become LO, must stand in relation to the limerent as one for whom the limerent is a potential sex partner".[9]

Willmott and Bentley define limerence as an acute onset, unexpected, obsessive attachment to one person (the limerent object). Limerence is characterised by internal experiences such as ruminative thinking, anxiety and depression, temporary fixation, and the disintegration of the self, and Willmott and Bentley found in their case studies that these themes find relation to unresolved earlier experiences and attempts at self-actualization.[3]

Limerence is sometimes also interpreted as infatuation, or what is colloquially known as a "crush". However, in common speech, infatuation includes aspects of immaturity and extrapolation from insufficient information, and is usually short-lived. Tennov notes how limerence "may dissolve soon after its initiation, as in an early teenage buzz-centered crush",[10] but she is more concerned with the point when "limerent bonds are characterized by 'entropy' crystallization as described by Stendhal in his 1821 treatise On Love, where a new love infatuation perceptually begins to transform ... [and] attractive characteristics are exaggerated and unattractive characteristics are given little or no attention ... [creating] a 'limerent object'".

According to Tennov, there are at least two types of love: "limerence", which she describes as, among other things, "loving attachment"; and "loving affection", the bond that exists between an individual and their parents and children.[11] She notes that one form may evolve into the other: "Those whose limerence was replaced by affectional bonding with the same partner might say ... 'We were very much in love when we married; today we love each other very much'".[12] The distinction is comparable to that drawn by ethologists "between the pair-forming and pair-maintaining functions of sexual activity",[6] just as "the attachment of the attachment theorists is very similar to the emotional reciprocation longed for in Tennov's limerence, and each is linked to sexuality".[13]

Nicky Hayes describes limerence as "a kind of infatuated, all-absorbing passion" which is unrequited. Tennov equated it to the type of love Dante felt towards Beatrice—an individual he met twice in his life and who served as inspiration for La Vita Nuova and the Divine Comedy. It is this unfulfilled, intense longing for the other person which defines limerence, where the individual becomes "more or less obsessed by that person and spends much of their time fantasising about them". Limerence may only last if conditions for the attraction leave it unfulfilled; therefore, occasional, intermittent reinforcement is required to support the underlying feelings. Hayes notes that "it is the unobtainable nature of the goal which makes the feeling so powerful", and that it is not uncommon for those to remain in a state of limerence over someone unreachable for months and even years.[14]: 457 A famous literary example of limerence is provided by the unrequited love of Werther for Charlotte in the novel The Sorrows of Young Werther by Goethe.

Limerence is characterized by intrusive thinking and pronounced sensitivity to external events that reflect the disposition of the limerent object towards the individual. It can be experienced as intense joy or as extreme despair, depending on whether the feelings are reciprocated. It is the state of being completely carried away by unreasoned passion or love, even to the point of addictive-type behavior. Usually, one is inspired with an intense passion or admiration for someone. Limerence can be difficult to understand for those who have never experienced it, and it is thus often dismissed by non-limerents as ridiculous fantasy or a construct of romantic fiction.[1]

Tennov differentiates between limerence and other emotions by asserting that love involves concern for the other person's welfare and feeling. While limerence does not require it, those concerns may certainly be incorporated. Affection and fondness exist only as a disposition towards another person, irrespective of whether those feelings are reciprocated, whereas limerence deeply desires reciprocation, but it remains unaltered whether or not it is returned. Physical contact with the object is neither essential nor sufficient to an individual experiencing limerence, unlike with one experiencing sexual attraction.[15] Where early, unhealthy attachment patterns or trauma influence limerence, the limerent object may be construed as an idealization of the figure or figures involved in the original unhealthy attachment or trauma. Lack of reciprocation may in such instances serve to reinforce lessons learned in earlier, unhealthy bonding experiences, and hence strengthen the limerence.

Components

Limerence involves intrusive thinking about the limerent object.[1] Other characteristics include acute longing for reciprocation, fear of rejection, and unsettling shyness in the limerent object's presence. In cases of unrequited limerence, transient relief may be found by vividly imagining reciprocation from the limerent object. Tennov suggests that feelings of limerence can be intensified through adversity, obstacles, or distance—'Intensification through Adversity'.[16] A limerent person may have acute sensitivity to any act, thought, or condition that can be interpreted favorably. This may include a tendency to devise, fabricate, or invent "reasonable" explanations for why neutral actions are a sign of hidden passion in the limerent object.

A person experiencing limerence has a general intensity of feeling that leaves other concerns in the background. In their thoughts, such a person tends to emphasize what is admirable in the limerent object and to avoid any negative or problematic attributes.

Intrusive thinking and fantasy

During the height of limerence, thoughts of the limerent object (or person) are at once persistent, involuntary, and intrusive. Such "intrusive thoughts about the LO ... appear to be genetically driven":[17] indeed, limerence is first and foremost a condition of cognitive obsession. This may be caused by low serotonin levels in the brain, comparable to those of people with obsessive–compulsive disorder.[18] All events, associations, stimuli, and experiences return thoughts to the limerent object with unnerving consistency, while conversely the constant thoughts about the limerent object define all other experiences. If a certain thought has no previous connection with the limerent object, immediately one is made. Limerent fantasy is unsatisfactory unless rooted in reality,[1] because the fantasizer may want the fantasy to seem realistic and somewhat possible. At their most severe, intrusive limerent thoughts can occupy an individual's waking hours completely, resulting—like severe addiction—in significant or complete disruption of the limerent's normal interests and activities, including work and family. For serial limerents, this can result in debilitating, lifelong underachievement in school, work, and family life.

Fantasies that are concerned with far-fetched ideas are usually dropped by the fantasizer.[1] Sometimes fantasizing is retrospective: actual events are replayed from memory with great vividness. This form predominates when what is viewed as evidence of possible reciprocation can be re-experienced (a kind of selective or revisionist history). Otherwise, the long fantasy is anticipatory; it begins in the everyday world and climaxes at the attainment of the limerent goal. A limerent fantasy can also involve an unusual, often tragic, event.

The long fantasies form bridges between the limerent's ordinary life and that intensely desired ecstatic moment. The duration and complexity of a fantasy depend on the availability of time and freedom from distractions. The bliss of the imagined moment of consummation is greater when events imagined to precede it are possible (though they often represent grave departures from the probable). It isn't always entirely pleasant, and when rejection seems likely the thoughts focus on despair, sometimes to the point of suicide. The pleasantness or unpleasantness of the state seems almost unrelated to the intensity of the reaction. Although the direction of feeling, i.e., happy versus unhappy, shifts rapidly, with 'dramatic surges of buoyancy and despair',[17] the intensity of intrusive and involuntary thinking alters less rapidly, and only in response to an accumulation of experiences with the particular limerent object.

Fantasies are occasionally dreamed by the one experiencing limerence. Dreams give out strong emotion and happiness when experienced, but often end with despair when the subject awakens. Dreams can reawaken strong feelings toward the limerent object after the feelings have declined.

Fear of rejection

Along with an emphasis on the perceived exceptional qualities, and devotion to them, there is abundant doubt that the feelings are reciprocated: rejection. Considerable self-doubt is encountered, leading to "personal incapacitation expressed through unsettling timidity in the presence of the person",[19] something which causes misery and galvanizes desire.

In most cases, what destroys limerence is a suitably long period of time without reciprocation. Although it appears that limerence advances with adversity, personal discomfort may foul it. This discomfort results from a fear of the limerent object's opinions.

Hope

Limerence develops and is sustained when there is a certain balance of hope and uncertainty. The basis for limerent hope is not in objective reality but in reality as it is perceived. The inclination is to sift through nuances of speech and subtleties of behavior for evidence of limerent hope. "Lovers, of course, are notoriously frantic epistemologists, second only to paranoiacs (and analysts) as readers of signs and wonders."[20] "Little things" are noticed and endlessly analyzed for meaning. Such excessive concern over trivia may not be entirely unfounded, however, as body language can indicate reciprocated feeling. What the limerent object said and did is recalled with vividness. Alternative meanings for the behaviors recalled are sought. Each word and gesture is permanently available for review, especially those interpreted as evidence in favor of reciprocated feeling. When objects, people, places or situations are encountered with the limerent object, they are vividly remembered, especially if the limerent object interacted with them in some way.

The belief that the limerent object does not and/or will not reciprocate can only be reached with great difficulty. Limerence can be carried quite far before acknowledgment of rejection is genuine, especially if it has not been addressed openly by the limerent object.

Loneliness

Shaver and Hazan observed that those suffering from loneliness are significantly more susceptible to limerence,[21] arguing that "if people have a large number of unmet social needs, and are not aware of this, then a sign that someone else might be interested is easily built up in that person's imagination into far more than the friendly social contact that it might have been. By dwelling on the memory of that social contact, the lonely person comes to magnify it into a deep emotional experience, which may be quite different from the reality of the event."[14]: 460

Effects

Physical

The physiological effects of intense limerence can include shortness of breath, perspiration, and heart palpitations.[22]

If there is extensive anxiety, incorrect behaviour may torpedo the relationship, which may cause physical responses to manifest intensely. Some people keenly feel these effects either immediately upon or after contact with the limerent object. What gets emotionally blended is blissful ecstasy and acute despair, depending on the turn of events.

Psychological

Awkwardness, stuttering, shyness, and confusion predominate at the behavioral level. Sufferers complain of abandonment, despair, and diabolically humiliating disappointment. A sense of paralyzing ambiguity predominates, punctuated by pining. Intermittent or nonreciprocal responses lead to labile vacillation between despair and ecstasy. This limbo is the threshold for mental prostration.

The sensitivity that stems from fear of rejection can darken perceptions of the limerent object's body language. Conflicted signs of desire may be displayed causing confusion. Often, the limerent object is involved with another or is in some other way unavailable.[23]

A condition of sustained alertness, a heightening of awareness and an enormous fund of energy to deploy in pursuit of the limerent aim is developed. The sensation of limerence is felt in the midpoint of the chest, bottom of the throat, guts, or in some cases in the abdominal region.[1] This can be interpreted as ecstasy at times of mutuality, but its presence is most noticeable during despair at times of rejection.

Sexuality

Awareness of physical attraction plays a key role in the development of limerence,[24] but is not enough to satisfy the limerent desire, and is almost never the main focus; instead, the limerent focuses on what could be defined as the "beneficial attributes". Nevertheless, Tennov stresses that "the most consistent desired result of limerence is mating, not merely sexual interaction but also commitment".[25]

Limerence can be intensified after a sexual relationship has begun, and with more intense limerence there is greater desire for sexual contact. However, while sexual surrender at one time indicated the end of uncertainty felt by the limerent object – because in the past, a sexual encounter more often led to a feeling of obligation to commit – in modern times this is not necessarily the case.

The sexual aspect of limerence is not consistent from person to person. Most limerents experience limerent sexuality as a component of romantic interest. Some limerents, however, may experience limerence as a consequence of hyperarousal. In such cases, limerence may form as a defense mechanism against the limerent object, who is not perceived initially as a romantic ideal, but as a physical threat to the limerent.

Sexual fantasies are distinct from limerent fantasies. Limerent fantasy is rooted in reality and is intrusive rather than voluntary. Sexual fantasies are under more or less voluntary control and may involve strangers, imaginary individuals, and situations that could not take place. Limerence elevates body temperature and increases relaxation,[26] a sensation of viewing the world with rose-tinted glasses, leading to a greater receptiveness to sexuality, and to daydreaming.[27]

People can become aroused by the thought of sexual partners, acts, and situations that are not truly desired, whereas every detail of the limerent fantasy is passionately desired actually to take place.[28] Limerence sometimes increases sexual interest in other partners when the limerent object is unreceptive or unavailable.[29]

Limerent duration

Tennov estimates, based on both questionnaire and interview data, that the average limerent reaction duration, from the moment of initiation until a feeling of neutrality is reached, is approximately three years. The extremes may be as brief as a few weeks or as long as several decades. When limerence is brief, maximum intensity may not have been attained. According to David Sack, M.D., limerence lasts longer than romantic love, but is shorter than a healthy, committed partnership.[30]

Others suggest that "the biogenetic sourcing of limerence determines its limitation, ordinarily, to a two-year span",[31] that limerence generally lasts between 18 months and three years; but further studies on unrequited limerence have suggested longer durations. In turn, a limerent may only experience a single limerent episode, or may experience "serial" episodes, in which nearly one's entire mature life, from early puberty through late adulthood, can be consumed in successive limerent obsessions.

Bond varieties

Once the limerent reaction has initiated, one of three varieties of bonds may form, defined over a set duration of time, in relation to the experience or non-experience of limerence.[32] The constitution of these bonds may vary over the course of the relationship, in ways that may either increase or decrease the intensity of the limerence.

The basis and interesting characteristic of this delineation made by Tennov, is that based on her research and interviews with people, all human bonded relationships can be divided into three varieties being defined by the amount of limerence or non-limerence each partner contributes to the relationship.[1]

With an affectional bond, neither partner is limerent. With a limerent–nonlimerent bond, one partner is limerent. In a limerent–limerent bond, both partners are limerent.

Affectional bonding characterize those affectionate sexual relationships where neither partner is limerent; couples tend to be in love, but do not report continuous and unwanted intrusive thinking, feeling intense need for exclusivity, or define their goals in terms of reciprocity. These types of bonded couples tend to emphasize compatibility of interests, mutual preferences in leisure activities, ability to work together, and in some cases a degree of relative contentment.

The bulk of relationships, however, according to Tennov, are those between a limerent person and a nonlimerent other, i.e. limerent–nonlimerent bonding. These bonds are characterized by unequal reciprocation.

Lastly, those relationship bonds in which there exists mutual reciprocation are defined as limerent–limerent bondings. Tennov argues that since limerence itself is an "unstable state", mutually limerent bonds would be expected to be short-lived; mixed relationships probably last longer than limerent-limerent relationships. Some limerent-limerent relationships evolve into affectional bondings over time as limerence declines. Tennov describes such couples as "old marrieds" whose interactions are typically both stable and mutually gratifying.

Mitigation

In her study Tennov identified three ways in which limerence subsides:

- Consummation (reciprocation)

- Each limerent has a slightly different view of acceptable reciprocation, and the reactions to reciprocation vary. Some limerents remain limerent (as documented by Tennov), while for others the limerence subsides as the certainty of reciprocity grows. Other limerents do not achieve any "real" consummation (e.g., physical, or in the form of an actual relationship) but find their limerence waning after a limerent object professes similar feelings.

- Starvation

- In this process, a lack of any notice (i.e., starvation, described by Tennov as "the onslaught of evidence that LO does not return the limerence") causes the limerent to gradually desensitize. This desensitization may take a long time, in which case a limerent's latent hypersensitivity may cause any attention given by a former LO, regardless of how slight, to be interpreted as a reason for hope, precipitating a resurgence of limerence.

- Transference

- The limerent transfers their romantic feelings to another person, thereby ending the initial limerence; the limerence is sometimes transferred as well.

Continuing research

Tennov's research was continued in 2008 by Albert Wakin, who knew Tennov at the University of Bridgeport but did not assist in her research, and Duyen Vo, a graduate student.[33] They intended to refine the term limerence so that it refers mostly to the negative aspects.

The term "limerence" has been invoked in many popular media, including self-help books, popular magazines, and websites. However, according to a paper by Wakin and Vo, "In spite of the public's exposure to limerence, the professional community, particularly clinical, is largely unaware of the concept."[22] In 2008, Wakin and Vo presented their updated research to the American Association of Behavioral and Social Sciences. They reported that more research must be gathered before the condition is suitable for inclusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).[33]

Critics point out that Tennov's account "is based on interviews rather than on direct observation", but conclude that "despite its shortcomings, Tennov's work may constitute a basis for informed hypothesis formulation".[34]

See also

- Agape – Greco-Christian term referring to God's love, the highest form of love

- Erotomania – Romantic delusional disorder

- Infatuation – Intense but shallow attraction

- Crystallization (love) – The "falling in love" process

- New relationship energy – State of mind during new relationship

- Obsessive love – Excessive desire to possess and protect another person

- Puppy love – Feelings of love, romance, or infatuation felt by young people

- Unconditional love – Concept of love without conditions

- Unrequited love – Love that is not reciprocated by the receiver

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tennov, Dorothy (1999). Love and Limerence: the Experience of Being in Love. Scarborough House. ISBN 978-0-8128-6286-7. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ↑ Willmott, Lynn (2012). Love and Limerence: Harness the Limbicbrain. Lathbury House. ISBN 978-1481215312.

- 1 2 Willmott, Lynn; Bentley, Evie (5 January 2015). "Exploring the Lived-Experience of Limerence: A Journey toward Authenticity". The Qualitative Report. Fort Lauderdale-Davie, Florida: Nova Southeastern University. 20 (1): 20–38. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ↑ Bowlby, John (1987). Gregory, Richard (ed.). Attachment. Oxford. p. 57.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Ågmo 2007, pp. 173, 186

- 1 2 Morris 1994, p. 223

- ↑ De Munck, V. C., ed. (1998). Romantic Love and Sexual Behavior. p. 5.

- ↑ (unknown), Wanda (21 January 1980). "Let's Fall in Limerence". Time. Time Inc. Archived from the original on 27 March 2008. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ↑ Tennov, Dorothy (1979). Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love. New York: Stein and Day. p. 24. ISBN 0-8128-2328-1.

- ↑ Leggett & Malm 1995, p. 86

- ↑ "That crazy little thing called love". The Guardian. 14 December 2003. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- ↑ Tennov 1998, p. 79

- ↑ Moore 1998, p. 260

- 1 2 Hayes, Nicky (2000), Foundations of Psychology (3rd ed.), London: Thomson Learning, ISBN 1861525893

- ↑ Diamond, Lisa. "Emerging Perspectives on Distinctions Between Romantic Love and Sexual Desire" (PDF). Current Directions in Psychological Science. 13: 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ Leggett & Malm 1995, p. 68

- 1 2 Moore 1998, p. 268

- ↑ Marazziti, D.; Akiskal, H. S.; Rossi, A.; Cassano, G. B. (1999). "Alteration of the platelet serotonin transporter in romantic love". Psychol. Med. 29 (3): 741–745. doi:10.1017/S0033291798007946. PMID 10405096. S2CID 12630172.

- ↑ Leggett & Malm 1995, p. 60

- ↑ Phillips, Adam. On Flirtation (London 1994) p. 41

- ↑ Shaver, Phillip; Hazan, Cindy (1985), "Incompatibility, Loneliness, and "Limerence"", in Ickes, W. (ed.), Compatible and Incompatible Relationships, Springer, New York, NY, pp. 163–184, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-5044-9_8, ISBN 978-1-4612-9538-9

- 1 2 Wakin, Albert H.; Vo, Duyen B. (2008). "Love-Variant: The Wakin-Vo I. D. R. Model of Limerence". Challenging Intimate Boundaries. Inter-Disciplinary — Net. 2nd Global Conference.

- ↑ Banker, Robin M. (2010). Socially Prescribed Perfectionism and Limerence in Interpersonal Relationships. University of New Hampshire (Department of Education).

- ↑ Tennov 1998, p. 96

- ↑ Tennov 1998, p. 82

- ↑ Gramann, Klaus; Shephard, Jennifer; Elliott, James; Kozhevnikov, Maria (29 March 2013). "Neurocognitive and Somatic Components of Temperature Increases during g-Tummo Meditation: Legend and Reality". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e58244. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...858244K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058244. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3612090. PMID 23555572.

- ↑ Giambra, L. M. (1979–1980). "Sex differences in daydreaming and related mental activity from the late teens to the early nineties". International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 10 (1): 1–34. doi:10.2190/01BD-RFNE-W34G-9ECA. ISSN 0091-4150. PMID 478659. S2CID 9265240.

- ↑ Lee, Coach (23 May 2019). "What Is Limerence?". My Ex Back Coach. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ↑ Banker, Robin (1 January 2010). "Socially prescribed perfectionism and limerence in interpersonal relationships". Master's Theses and Capstones.

- ↑ Sack, David (28 June 2012). "Limerence and the Biochemical Roots of Love Addiction" (web). Huffington Post. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ↑ Leggett & Malm 1995, p. 139

- ↑ Diamond, Lisa. "Emerging Perspectives on Distinctions Between Romantic Love and Sexual Desire" (PDF). Current Directions in Psychological Science. 13: 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- 1 2 Jayson, Sharon (6 February 2008). "'Limerence' makes the heart grow far too fonder" (web). USA Today. Gannett Co. Inc. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ↑ Ågmo 2007, p. 172

Bibliography

- Ågmo, Anders (17 August 2007). Functional and dysfunctional sexual behavior: a synthesis of neuroscience and comparative psychology. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-370590-7. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- Badiane, Fatu. The Chemistry of Cupid's Arrow. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- Diamond, Lisa M. Emerging Perspectives on Distinctions Between Romantic Love and Sexual Desire (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- Grohol, J. (2006). Love Versus Infatuation. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- Hendrix, Harville (February 1992). Keeping the love you find: a guide for singles. Pocket Books. ISBN 978-0-671-73419-0. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- Leggett, John C.; Malm, Suzanne (March 1995). The Eighteen Stages of Love: Its Natural History, Fragrance, Celebration and Chase. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-882289-33-2. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- Moore, Robert L. (1998). "Love and Limerence with Chinese Characteristics". In De Munck, V. C. (ed.). Romantic love and sexual behavior: perspectives from the social sciences. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-95726-1. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- Morris, Desmond (2 June 1994). The naked ape trilogy. J. Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-04140-9. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- Tennov, Dorothy (2005). "A Scientist Looks at Romantic Love and Calls It "Limerence": The Collected Works of Dorothy Tennov". Greenwich, Ct.: The Great American Publishing Society.

- Tennov, Dorothy (1998). "Love Madness". In De Munck, V. C. (ed.). Romantic love and sexual behavior: perspectives from the social sciences. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-95726-1. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- Webb, Frances Sizer; Whitney, Eleanor Noss; DeBruyne, Linda K. (2000). Health: making life choices. West Educational Pub. pp. 494–496. ISBN 978-0-538-69066-9. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

External links

- New Relationship Energy FAQ – comparison between NRE and limerence

- Support forum for those impacted by limerence at Limerence.net