Dauphiné

| |

|---|---|

Flag  Coat of arms | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Country | France |

| Time zone | CET |

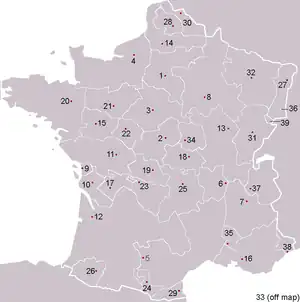

The Dauphiné (UK: /ˈdoʊfɪneɪ, ˈdɔː-/, US: /ˌdoʊfiːˈneɪ/ French: [dofi'ne])[1][2] is a former province in southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of Isère, Drôme and Hautes-Alpes. The Dauphiné was originally the Dauphiné of Viennois.

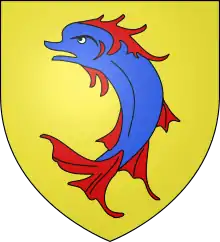

In the 12th century, the local ruler Count Guigues IV of Albon (c. 1095–1142) bore a dolphin on his coat of arms and was nicknamed le Dauphin (French for 'dolphin'). His descendants changed their title from Count of Albon to Dauphin of Viennois. The state took the name of Dauphiné. It became a state of the Holy Roman Empire in the 11th century.

In 1349, the Dauphiné was transferred from the last non-royal Dauphin (who had great debts and no direct heir) to the future king of France, Charles V, through the purchase of lands. The terms of the transfer stipulated that the heir apparent of France would henceforth be called le Dauphin and included significant autonomy and tax exemption for the Dauphiné region, most of which it retained only until 1457, though it remained a province until the French Revolution. Dauphin of France remained the title of the eldest son of a king of France and the heir apparent to the French crown until 1830.

The historical capital is Grenoble and the other main towns are Vienne, Valence, Montélimar, Gap and Romans-sur-Isère. The demonym for its inhabitants is Dauphinois.

Geography

Under the Ancien Régime, the province was bordered in the North by the River Rhône which separated the Dauphiné from the Bresse ("Brêsse") and Bugey ("Bugê"). To the east it bordered the Savoy and Piedmont, and to the south the Comtat Venaissin and Provence. The western border was marked by the Rhône to the south of Lyon. The Dauphiné extended up to what is now the centre of Lyon. It was divided into the "High Dauphiné" and "Low Dauphiné". The first covered:

- the Grésivaudan

- the Royans

- the Champsaur

- the Trièves

- the Briançonnais

- the Queyras

- the Embrunais

- the Gapençais

- the Dévoluy

- the Vercors

- the Bochaine

- the Baronnies

The second included:

- the County of Albon with the Viennois around the city of Vienne, annexed in 1450 and the Turripinois around the city of La Tour-du-Pin.

- the County of Valentinois with the city of Valence, annexed in 1404

- the County of Diois, around the episcopal city of Die, also annexed in 1404

- the Tricastin

- the Principality of Orange annexed to Dauphiné, (in 1793 it was included in the Vaucluse)

The province also included the current Italian Dauphiné, which belonged to France and to Briançonnais until 1713. Vivaro-Alpine dialect was still spoken there until the 20th century:

- the Oulx valley

- the Pragela (Pragelato et Val Chisone)

- the Castelade de Châteaudauphin (Casteldelfino in Italian).

The province offers a range of terrain, from the alpine summits of the High-Dauphiné (the Barre des Ecrins is 4,102 meters at its highest point), the Prealps (Vercors and Chartreuse), and the plains of the Drôme, which resemble the landscapes of Provence.

History

Classical Antiquity and The Middle Ages

Roman rule and the early Middle Ages

The area of the future Dauphiné was inhabited by the Allobroges and other Gaulish tribes in ancient times. The region was conquered by the Romans before the Gallia conquest by Julius Caesar. Vienne became a Roman colony and one of the most important cities of Gallia.

After the end of the Western Roman Empire, the region suffered from invasions of Visigoths and Alans tribes. The Burgundians settled in Vienne.[3] After the Treaty of Verdun in 843, the region became part of the kingdom of Lotharingia. However, the King of France Charles the Bald soon claimed authority over this territory.

The governor of Vienne, Boson of Provence, proclaimed himself king of Burgundy and the region became part of the Kingdom of Burgundy, which remained independent until 1032, when it became part of the Holy Roman Empire.[4]

At that time, the development of feudal society and the weakness of the Emperor's rule allowed for the creation of several small ecclesiastic or secularist States (the region of Viennois, for example, was under the rule of the archbishop of Vienne). In the middle of that chaos, the Counts of Albon succeeded in uniting these different territories under their rule.[5]

Imperial fief (1040–1349)

Amidst the chaos of feudal rule, the Counts of Albon began to rise above other feudal lords and acquire dominance over the region. Their story begins with Guigues I the Old (died 1070), Lord of Annonay and Champsaur. During his reign, he gained significant territories for his province: a part of the Viennois, the Grésivaudan and the Oisans. Moreover, the Emperor gave him the region of Briançon. The territories combined under his personal rule became a sovereign mountain principality within the Holy Roman Empire. The count made a significant decision when[6] he chose the small city of Grenoble as capital of his state instead of the prestigious city of Vienne, which was the long-established seat of a powerful bishop. This choice allowed him to assert authority over all his territories.

In the 12th century, the local ruler Count Guigues IV of Albon (c.1095–1142) bore a dolphin on his coat of arms and was nicknamed le Dauphin (French for dolphin). His descendants changed their title from Count of Albon to Dauphin of Viennois. The state took the name of Dauphiné.

However, the Dauphiné did not, at this point, have its modern borders. The region of Vienne and Valence were independent and even in Grenoble, the capital, the authority was shared with the bishop. Furthermore, the cities of Voiron and la Côte-Saint-André were parts of the County of Savoy, while the Dauphins had the Faucigny and territories in Italy. This tangle between Dauphiné and Savoy resulted in several conflicts. The last Dauphin, Humbert II of Viennois, made peace with his neighbour. He also acquired the city of Romans. He finally created the Conseil Delphinal and the University of Grenoble and enacted the Delphinal Status, a kind of constitution that protected the rights of his people.

French rule

The significant debts of Humbert II and the death of his son and heir led to the sale of his lordship to King Philip VI in 1349, by the terms of the treaty of Romans, negotiated by his protonotary, Amblard de Beaumont. A major condition was that the heir to the throne of France would be known as le Dauphin, which was the case from that time until the French Revolution; the first Dauphin de France was Philippe's grandson, the future Charles V of France. The title[7] also conferred an appanage on the region. Charles V spent nine months in his new territory.

Humbert's agreement further stipulated that Dauphiné would be exempted from many taxes (like the gabelle); this statute was the subject of much subsequent parliamentary debate at the regional level, as local leaders sought to defend this regional autonomy and privilege from the state's assaults.

The nobility of the Dauphiné took part in the battles of Poitiers (1356) and Agincourt (1415). The province was also the setting for military events during the war. The Duke of Savoy and the Prince of Orange, with the help of the English and Burgundian authorities, planned to invade the Dauphiné, but at the battle of Anthon in 1430, the army of the Principality of Orange was defeated by the troops of the Dauphiné, preventing the invasion.

Louis XI was the only Dauphin of France to administer his territory, from 1447 to 1456. It was during his reign as Dauphin that the Dauphiné became totally integrated into France. At that time, it was an anarchic state, with conflicts between nobles still common.[8] Louis XI prohibited these conflicts and forced the nobles to recognize his authority. The Conseil Delphinal became the third Parlement of France. Moreover, Louis XI politically united the Dauphiné. He forced the archbishop of Vienne, the bishop of Grenoble and the abbot of Romans all to pledge allegiance to him. He also acquired Montélimar and the Principality of Orange.

In addition, he developed the economy of the province, by constructing roads and authorizing markets. He finally created the University of Valence founded 26 July 1452, by letters patent. Nevertheless, he also tried to institute the gabelle without referring the issue to the estates of the province, resulting in discontent on the part of the nobility and the people of the province. Because of his opposition to his father, Charles VII, he was forced to leave the Dauphiné. The King took back the control of the province and forced the Estates to pledge allegiance in 1457.[9]

Imperial suzerainty was not entirely forgotten in the 15th century. The Emperor Sigismund negotiated with King Henry V of England to give the Dauphiné to an English prince. The Dauphinois also did not forget their autonomy. The Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges (1438), which exposed Gallicanism, and the Concordat of Bologna (1516), which rectified France with the Papacy, were both promulgated for France and the Dauphiné distinctly. The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts (1539), on the other hand, which made French the official language of France, since it was not issued by the king as dauphin was not recognised in the Dauphiné. A second ordinance was promulgated at Abbeville on 9 April 1540 by the king as dauphin and this the Dauphinois parliament accepted.[10]

Early modern history

Time of troubles

%252C_Mus%C3%A9e_de_la_R%C3%A9volution_fran%C3%A7aise_-_Vizille.jpg.webp)

During the Italian Wars (1494–1559), French troops were quartered in Dauphiné. Charles VIII, Louis XII and Francis I stayed often in Grenoble, but the people of the province suffered the exactions of the soldiers. Moreover, the nobility of the region took part in the different battles (Marignano, Pavia) and gained an immense prestige.[11] The best-known of its members was Pierre Terrail de Bayard, "the knight without fear and beyond reproach".

The province suffered from the French Wars of Religion (1562–98) between Catholics and Protestants at the end of the 16th century. The Dauphiné was a center of Protestantism in France, in cities such as Gap, Die, and La Mure. François de Beaumont, the Huguenot leader, became famous for his cruelty and his destructions.

The cruel execution of Charles du Puy-Montbrun, leader of the Protestants, by the king of France, led to more violence and struggles between the two parties.

In 1575, Lesdiguières became the new leader of the Protestants and obtained several territories in the province. After the accession of Henry IV to the throne of France, Lesdiguières allied with the governor and the lieutenant general of Dauphiné. However, this alliance did not put an end to the conflicts. Indeed, a Catholic movement, la Ligue, which took Grenoble in 1590, refused to make peace. After months of assaults, Lesdiguières defeated the Ligue and took back Grenoble. He became the leader of the entire province.[12]

Administration of Lesdiguières (1591–1626)

The conflicts were over, but Dauphiné was destroyed and its people exhausted. The enactment of the Edict of Nantes (1598) restored some civil rights to the Huguenots and brought peace for a short time, but the wars resumed soon afterward.

Lesdiguières defeated the army of Savoy several times and helped the reconstruction of the region. His most famous construction is the Palace of Vizille, built for his personal use.

The last meeting of the Estates of Dauphiné took place in 1628. It symbolizes the end of the liberty of the province. From that time, the important decisions were taken by the representatives of the king. It shows the progress of Absolutism.

From Louis XIV to the French Revolution

The revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV in 1685 caused the departure of 20,000 Protestants from Dauphiné, weakening the economy of the province. Some valleys lost half of their inhabitants.[13]

In 1692, during the Nine Years' War, the Duke of Savoy invaded the Dauphiné. Gap and Embrun were badly damaged. But the Savoy armies were defeated by the French Marshal Nicolas Catinat and Philis de La Charce leading a peasant army.[14]

In 1713, the Treaty of Utrecht changed the borders of Dauphiné. The province gained the town of Barcelonette but lost the major part of the Briançonnais.

The 18th century was a period of economic prosperity for the region, with the development of the industry (glove-making in Grenoble, silk mills in the Rhône valley). Important trade shows also occurred at Grenoble or Beaucroissant.

In 1787, the province was one of the first to demand the meeting of the Estates General of France. The turning point occurred in 1788 with the Day of the Tiles. The King ordered the expulsion of the parliamentarians from Grenoble. In part because the economy of the city was dependent on its Parliament, the local people attacked the royal troops by throwing tiles from roofs to prevent the expulsion of the magistrates. This event allowed the sitting of the Assembly of Vizille, which instigated the meeting of the old Estates General, thus beginning the Revolution.

Modern history

Revolutionary period and Empire

During the French Revolution, Dauphiné was highly represented in Paris by two illustrious notables from Grenoble, Jean Joseph Mounier and Antoine Barnave.

In 1790, Dauphiné was divided in three departments, the current Isère, Drôme, and Hautes-Alpes.[15]

The approval of the establishment of the Empire was clear and overwhelming in the Dauphiné. In Isère, the results showed 82,084 yes and only 12 no.[16]

In 1813, Dauphiné was under the threat of the Austrian army which had invaded Switzerland and Savoy. After having resisted at Fort Barraux, the French troops withdrew to Grenoble. The city, well-defended, contained the Austrian attacks, and the French army defeated the Austrians, forcing them to withdraw at Geneva. But the invasion of France in 1814 resulted in the capitulation of the troops in Dauphiné.

During his return from the island of Elba in 1815, the Emperor was welcomed by the people in the region. At Laffrey, he met the royalist 5th Infantry Regiment of Louis XVIII. Napoleon stepped towards the soldiers and said those famous words: "If there is among you a soldier who wants to kill his Emperor, here I am." The men all joined his cause. Napoleon was then acclaimed at Grenoble. After the defeat at Waterloo, the region suffered from a new invasion of Austrian and Sardinian troops.

19th century

This century corresponds to a significant industrial development of Dauphiné, particularly in the region of Grenoble (glove-making reached its Golden Age at that time) and the Rhone Valley (silk mills). The shoemaking industry also developed in Romans.

During the Second Empire, the Dauphiné saw the construction of its railway network (the first trains arrived at Valence in 1854 and Grenoble in 1858). The driving of new roads in the Vercors and Chartreuse ranges allowed the beginning of tourism in the province. Moreover, several notable persons such as Queen Victoria came in the region with the success of thermal stations such as Uriage-les-Bains.

In 1869, Aristide Berges played a major role in industrializing hydroelectricity production. With the development of his paper mills, industrial development spread to the mountainous region of Dauphiné.

20th century

During the Belle Époque, the region benefited from major transformations thanks to its economic growth. The Romanche Valley became one of the most important industrial valleys of the country.[17] World War I accelerated that trend. Indeed, in order to sustain the war efforts, new hydroelectric industries settled next to different rivers of the region. Several other businesses moved into armament industries. Chemical companies also settled in the region of Grenoble and near Roussillon in the Rhone Valley.

The textile industry of Dauphiné also benefited from the war. The occupation of northern France resulted in the settlement of many textile enterprises in the region. Vienne for instance produced one fifth of the national production of sheets for the army in 1915.[18]

Several Alpine troops, the Chasseurs Alpins, were killed at war. They were nicknamed the "Blue Devils" for their courage on the field.

The economic development of the region was highlighted by the organisation at Grenoble of the International Exposition of the "Houille Blanche" in 1925, visited by thousands of people.

The interwar period was also characterized by the beginning of the winter sports in Dauphiné. The ski resort of l'Alpe d'Huez was constructed in 1936, and Jean Pomagalski created there the first platter lift in the world.

In World War II, during the Italian invasion of France, the Chasseurs Alpins contained the Italian troops, preventing an invasion of the region. But the German victories in northern France quickly threatened the troops in Dauphiné. The Nazis were stopped near Grenoble, at Voreppe. The French forces resisted until the armistice. The Dauphiné was then part of the French State, before being occupied by the Italians from 1942 to 1943, when the Germans occupied southern France.

Due to its mountainous character, Dauphiné was the seat of strong partisan activity. The best known was the Maquis du Vercors. In 1944, its members suffered from German attacks. The martyr village of Vassieux as well as Grenoble were made Compagnon de la Libération by General Charles de Gaulle, to underline their actions against the Nazis.[19]

In 1947, a bicycle race was created by a newspaper Le Dauphiné libéré to promote its circulation. After World War II, as cycling recovered from a universal five- or six-year hiatus, the Grenoble-based newspaper decided to create and organize a cycling stage race covering the Dauphiné region. This created the Critérium du Dauphiné before 2010 known as the Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré, is an annual cycling road race in the Dauphiné region. The race is run over eight days during the first half of June. It is part of the UCI World Tour calendar and counts as one of the foremost races in the lead-up to the Tour de France in July, along with the Tour de Suisse in the latter half of June.

In 1968, Grenoble welcomed the Xth Olympic Winter Games, allowing a major transformation of the city, the development of infrastructure (airport, motorways, etc.) and new ski resorts (Chamrousse, Les Deux Alpes, Villard-de-Lans, etc.).

Demography

The various territories of Dauphiné experienced diverging demographic evolutions. The plains of Low Dauphiné and the large cities saw their population strongly increase during the 20th century (thanks to the industrial development and immigrant workers' arrival), while the mountainous regions of High-Dauphiné suffered from a pronounced exodus.

These days, the entire territory is experiencing population growth because of economic development and tourism.

| Territory | 1801 | 1851 | 1901 | 1954 | 1975 | 1999 | 2007 | 2012 | 2017 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drôme department[20] | 235,357 | 327,000 | 297,000 | 275,280 | 361,847 | 437,778 | 473,428 | 491,334 | 511,553 | ||

| Hautes-Alpes department[21] | 112,500 | 132,000 | 109,510 | 85,067 | 97,358 | 121,419 | 132,482 | 139,554 | 141,284 | ||

| Isère department[22] | 413,109 | 578,000 | 544,000 | 587,975 | 860,339 | 1,094,006 | 1,178,714 | 1,224,993 | 1,258,722 | ||

| Dauphiné (sum) | 760,966 | 1,037,000 | 950,510 | 948,322 | 1,319,544 | 1,653,203 | 1,784,624 | 1,855,881 | 1,911,559 | ||

| Source : INSEE | |||||||||||

The population of the Dauphiné was relatively stable until the mid-20th century, when growth became more rapid. However it should be remembered that several cities of northern Dauphiné (Villeurbanne, Vénissieux, Bron and others) are included in the Lyon Metropolis. In 1999, the population of these cities was over 460,000.

Histogram of the evolution since 1801:

Dauphiné has a population density of 98.0/km2, with a very clear differentiation between Isère (169/km2) and Hautes-Alpes (26/km2).

Grenoble concentrates around a third of the population of Dauphiné, and Valence is now the second largest Dauphiné metropolis. Dauphiné also has a network of mid-sized cities covering all its territory (Vienne, Montélimar, Gap, etc.). A considerable part of the Isère department lies in the functional urban area of Lyon, including the cities Vienne, L'Isle-d'Abeau and Bourgoin-Jallieu.

| Urban area | Population (2018) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Grenoble | 714,799 |

| 2 | Valence† | 254,254 |

| 3 | Montélimar† | 98,989 |

| 4 | Gap† | 80,555 |

| 5 | Romans-sur-Isère | 65,490 |

| 6 | Roussillon† | 62,595 |

| 7 | Pierrelatte† | 46,931 |

| 8 | Saint-Marcellin | 23,259 |

| 9 | Briançon | 23,244 |

| 10 | Crest | 17,555 |

| †Note: part of the urban area is outside Dauphiné | ||

Gastronomy

Dauphiné is known for some culinary specialities:

- Raviole du Dauphiné

- gratin dauphinois

- pommes dauphines

- Saint-Marcellin

- Saint-Félicien

- Picodon

- Bleu du Vercors-Sassenage[24] (previously bleu de Sassenage)

- Nougat de Montélimar

- Coteaux du Tricastin

- clairette de Die

- Chartreuse (verte, jaune, etc.)

- crozes-hermitage

- Hermitage

Other meanings

The Dauphiné, or the Critérium du Dauphiné (formerly the [Critérium du] Dauphiné libéré, after the newspaper Le Dauphiné libéré that until 2010 had been sponsoring the event since its creation in 1947), is a multiple stage bicycle race. Amongst its winners one saw many of the most famous cyclists, e.g.: Louison Bobet, Henry Anglade, Jacques Anquetil, Raymond Poulidor, Luis Ocaña, Eddy Merckx, Bernard Thévenet, Bernard Hinault, Greg LeMond (by disqualification of the first arrived Pascal Simon[25]), Phil Anderson, Luis Herrera, Charly Mottet, Miguel Indurain, Alexander Vinokourov, Tyler Hamilton, Alejandro Valverde, Bradley Wiggins and Chris Froome.[26] Annually during a week in June, cycling fans in most European countries watch the prestigious road race in and around the Dauphiné area on live television.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ↑ Occitan: Daufinat or Dalfinat; Arpitan: Dôfenât or Darfenât; former English name: Dauphiny)

- ↑ Petite histoire du Dauphiné , Félix Vernay, 1933, p22

- ↑ Petite Histoire…, Félix Vernay, 1933, p24

- ↑ Petite histoire… , Félix Vernaix, 1933, p25

- ↑ Félix Vernay, Petite histoire du Dauphiné, 1933, p9

- ↑ The Crown of France also absorbed Humbert's other titles: prince du Briançonnais, duc de Champsaur, marquis de Cézanne, comte de Vienne, d'Albon, de Grésivaudan, d'Embrun et de Gapençais, baron palatine of La Tour, La Valbonne, Montauban and Mévouillon.

- ↑ Georges Bordonove, Les Valois, 2007, p1045

- ↑ Félix Vernay, Petite histoire du Dauphiné, 1933, p. 58

- ↑ Gustave Dupont-Ferrier, "Où en était la formation de l'unité française aux XVe et XVIe siècles ? Premier article", Journal des savants (1941): 10–24.

- ↑ Petite histoire du Dauphiné, Félix Vernay, 1933, p78

- ↑ Petite Histoire du Dauphiné , Félix Vernay, 1933, p88

- ↑ Petie Histoire…, Félix Vernay, 1933, p97

- ↑ AUED, par (8 July 2020). "Philis de la Charce". Études drômoises (in French). Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ↑ "Dauphiné, divisé en trois départemens suivant le décrêt de l'assemblée nationale, sanctionné par le roi; avec toutes les routes, et les distances en lieuës d'usage dans ces pays". Europeana. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ↑ Petite Histoire du Dauphiné, Félix Vernay, 1933, p. 115.

- ↑ L’histoire de l'Isère en BD, Tome 5, Gilbert Bouchard, 2004, p40

- ↑ L’histoire de l'Isère en BD, Tome 5, Gilbert Bouchard, 2004, p42

- ↑ "Ordredelaliberation.fr". Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- ↑ "INSEE: Drôme – Population en historique depuis 1968".

- ↑ "INSEE: Hautes-Alpes – Population en historique depuis 1968".

- ↑ "INSEE: Isère – Population en historique depuis 1968".

- ↑ Insee – Comparateur de territoire

- ↑ "Francefromages.com". Archived from the original on 18 April 2006. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ↑ Jones, Jeff; Maloney, Tim (2004). "Pre-Tour showdown at the Dauphiné-Libéré". Cyclingnews Future Publishing Ltd. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ "History - Race winners since 1947". Critérium du Dauphiné. Official site. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

Further reading

- Coolidge, William Augustus Brevoort (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). p. 851.

- Félix Vernay, Petite Histoire du Dauphiné, 1933.

- Pfeiffer, Thomas, Le Brûleur de loups, Lyon, Bellier, 2004.

External links

Media related to Dauphiné at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dauphiné at Wikimedia Commons