| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

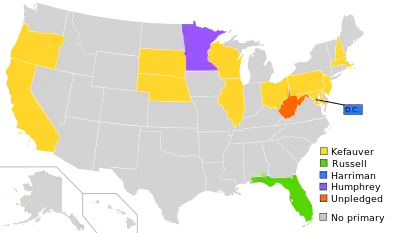

From March 11 to June 3, 1952, voters and members of the Democratic Party elected delegates to the 1952 Democratic National Convention, partly for the purpose of choosing a nominee for president in the 1952 United States presidential election. Incumbent President Harry S. Truman declined to campaign for re-election after losing the New Hampshire primary to Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee. Kefauver proceeded to win a majority of the popular vote, but failed to secure a majority of delegates, most of whom were selected through other means.

The 1952 Democratic National Convention, held from July 21 to July 26, 1952, in Chicago, was forced to go multiballot.[1] The nomination went to Adlai Stevenson II, the governor of Illinois.

Candidates

The following political leaders were candidates for the 1952 Democratic presidential nomination:

Major candidates

These candidates participated in multiple state delegate election contests or were included in multiple major national polls.

| Candidate | Most recent position | Home state | Campaign | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estes Kefauver | _(3x4).jpg.webp) |

U.S. Senator from Tennessee (1949–63) |

Tennessee |

(Campaign) | |

| Richard Russell Jr. |  |

U.S. Senator from Georgia (1933–71) |

.svg.png.webp) Georgia |

||

| W. Averell Harriman |  |

Diplomat Former Secretary of Commerce (1946–48) |

.svg.png.webp) New York |

||

| Harry S. Truman | .jpg.webp) |

President of the United States (1945–53) |

Missouri |

(Campaign) Declined: March 29, 1952 (supported Stevenson) | |

| Adlai Stevenson II |  |

Governor of Illinois (1949–53) |

Illinois |

(Campaign) | |

| Robert S. Kerr |  |

Senator from Oklahoma (1949–63) |

Oklahoma |

||

| Paul Dever |  |

Governor of Massachusetts (1949–53) |

Massachusetts |

||

Favorite sons

The following candidates ran only in their home state's primary or caucus for the purpose of controlling its delegate slate at the convention and did not appear to be considered national candidates by the media.

- State Attorney General Pat Brown of California

- Senator Robert J. Bulkley of Ohio

- Mayor Jerome F. Fox of Wisconsin

- Senator J. William Fulbright of Arkansas

- Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota

- Senator Brien McMahon of Connecticut

- Senator James E. Murray of Montana

- Senator Matthew M. Neely of West Virginia

- Governor G. Mennen Williams of Michigan

Polling

National polling

Before 1951

| Poll source | Publication | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallup | Nov. 23, 1949 | 12% | 3% | – | – | 22% | – | 44% | 3% | 6%[lower-alpha 2] | 14% |

| Gallup | Apr. 9, 1950 | 14% | 4% | 6% | – | 13% | 3% | 45% | 2% | 3%[lower-alpha 3] | 9% |

| Gallup[2] | Oct. 14, 1950 | 16% | 4% | 7% | 9% | 12% | 6% | 35% | – | 3%[lower-alpha 4] | 8% |

- ↑ Favorite sons received the support of Massachusetts (Paul Dever), Connecticut, Michigan, Kentucky (Alben Barkley), Arkansas (J. William Fulbright), Minnesota (Hubert H. Humphrey), and Montana.

- ↑ Scott Lucas with 2%, Chester Bowles with 2%, Louis Johnson with 1%, and 1% combined for Frank Lausche and Charles F. Brannan

- ↑ Harry F. Byrd with 3% and Fred Vinson 2%

- ↑ Other candidates with 3%

1951

| Poll source | Publication | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallup | Apr. 15, 1951 | 9% | 2% | 43% | 3% | 3% | 9% | 18% | 2% | 4%[lower-alpha 1] | 7% |

| Gallup[3] | June 17, 1951 | 8% | 3% | 40% | 3% | 4% | 9% | 20% | 2% | 6%[lower-alpha 2] | 5% |

1952

| Poll source | Publication | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallup[4] | Feb. 15, 1952 | 17% | 7% | 8% | 21% | – | – | 36% | 6% | – | 5% |

| Gallup | Apr. 1952 | 8% | – | 5% | 33% | 7% | 2% | 32% | 4% | 4%[lower-alpha 1] | 5% |

| 16% | 7% | 43% | 8% | 4% | – | 7% | 5%[lower-alpha 2] | 10% | |||

| Gallup[5] | May 8, 1952 | 8% | [lower-alpha 3] | [lower-alpha 3] | 41% | 9% | 11% | – | [lower-alpha 3] | 27%[lower-alpha 4] | 4% |

| Gallup[6] | June 7, 1952 | 17% | – | – | 45% | 10% | 10% | – | – | 9%[lower-alpha 5] | 9% |

| Gallup[7] | July 14, 1952 | 18% | – | – | 45% | 10% | 12% | – | – | 9%[lower-alpha 6] | 6% |

- ↑ Others with 4%

- ↑ Others with 5%

- 1 2 3 Candidate included among "other" choices

- ↑ Other votes split between Franklin Roosevelt Jr., Robert Kerr, Fred Vinson, James Farley, William Douglas, Paul Douglas, Harry Byrd, and W. Averell Harriman

- ↑ W. Averell Harriman with 5%, Robert Kerr with 3%, Brien McMahon with 1%

- ↑ W. Averell Harriman with 5%, Robert Kerr with 2%, Brien McMahon with 1%, Others with 1%

Primary race

The 1952 primary season was one of only two where a challenge to an incumbent president of either party was successful, the other being 1968. Prior to this, the last incumbent to try and fail to win his party's nomination was Chester Arthur in 1884 on the Republican side, and Andrew Johnson in 1868 on the Democratic.

The decline and fall of President Truman

The expected candidate for the Democratic nomination was incumbent President Harry S. Truman. Though running for a third term, he was grandfathered by the Twenty-second Amendment which exempted Truman from term limits. However, Truman entered 1952 with his opinion poll popularity plummeting. The bloody and indecisive Korean War was dragging into its third year, Senator Joseph McCarthy's anti-Communist crusade was stirring public fears of an encroaching “Red Menace”, and the disclosure of widespread corruption among federal employees (including some high-level members of Truman's administration) left Truman at a low political ebb.

Truman's main opponent was populist Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver, who had chaired a nationally televised investigation of organized crime in 1951 and was known as a crusader against crime and corruption. The Gallup poll of February 15 showed Truman's weakness: nationally Truman was the choice of only 36% of Democrats, compared with 21% for Kefauver. Among independent voters, however, Truman had only 18% while Kefauver led with 36%. In the New Hampshire primary Kefauver upset Truman, winning 19,800 votes to Truman's 15,927 and capturing all eight delegates. Kefauver graciously said that he did not consider his victory "a repudiation of Administration policies, but a desire...for new ideas and personalities." Stung by this setback, Truman soon announced that he would not seek re-election (however, Truman insisted in his memoirs that he had decided not to run for re-election well before his defeat by Kefauver).

The rise of Estes Kefauver

With Truman's withdrawal, Kefauver became the front-runner for the nomination, and he won most of the primaries. Nonetheless, most states still chose their delegates at the Democratic Convention via state conventions, which meant that the party bosses - especially the mayors and governors of large Northern and Midwestern states and cities - were able to choose the Democratic nominee. These bosses (including President Truman) strongly disliked Kefauver; his investigations of organized crime had revealed connections between mafia figures and many of the big-city Democratic political organizations. The party bosses thus viewed Kefauver as a maverick who could not be trusted, and they refused to support him for the nomination. Instead, with President Truman taking the lead, they began to search for other, more acceptable, candidates. However, most of the other candidates had a major weakness. Senator Richard Russell of Georgia had much Southern support, but his support of racial segregation and opposition to civil rights for Southern blacks led Northern delegates to reject him as a racist. Truman favored U.S. diplomat W. Averell Harriman of New York, but he had never held an elective office and was inexperienced in politics. Truman next turned to his Vice-President, Alben Barkley, but at 74 he was rejected as being too old by labor union leaders.

Stevenson

One candidate soon emerged who seemingly had few political weaknesses: Governor Adlai Stevenson II of Illinois. The grandson of former Vice-President Adlai E. Stevenson, Stevenson came from a distinguished family in Illinois and was well known as a gifted orator, intellectual, and political moderate. In the spring of 1952 President Truman tried to convince Stevenson to take the presidential nomination, but Stevenson refused, stating that he wanted to run for re-election as Governor of Illinois. Yet Stevenson never completely took himself out of the race, and as the convention approached, many party bosses – as well as normally apolitical citizens – hoped that he could be "drafted" to run.

Democratic National Convention

The 1952 Democratic National Convention was held in the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, the same venue where the Republicans had gathered two weeks earlier. The primary season had been decisively in Kefauver's favor and he had momentum coming in, but President Truman was still angry at "Cow-Fever's" defeat of him in New Hampshire, and the Tennessee Senator was unable to get enough delegate strength to win the nomination outright due to the delegate selection processes in most of the states at the time. The convention itself would prove, in retrospect, the last of its kind.

See also

References

- ↑ Kalb, Deborah (2016-02-19). Guide to U.S. Elections - Google Books. ISBN 9781483380353. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- ↑ Gallup, George (15 Oct 1950). "Truman's Renomination in '52 Approved by Party Voters". The Washington Post. p. M8.

- ↑ Gallup, George (17 June 1951). "Eisenhower Tops Poll of Democrats: Both Parties Favor Him for Presidency, Gallup Survey Shows". Los Angeles Times. p. 9.

- ↑ Gallup, George (15 Feb 1952). "Truman Ahead in Poll but Kefauver Is Gaining Fast: Gallup Survey Finds Tennessee Senator Is Overwhelming Choice of Independents". Los Angeles Times. p. 6.

- ↑ Gallup, George (9 May 1952). "Kefauver Leads In Popularity With Rank and File Democrats". The Washington Post. p. 3.

- ↑ Gallup, George (8 June 1952). "Kefauver Gains Steadily In Democratic Contest". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. p. 10B.

- ↑ Gallup, George (14 July 1952). "County Chairmen Want Stevenson, but Most Voters Prefer Kefauver". The Boston Globe. p. 3.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)