| Dune | |

|---|---|

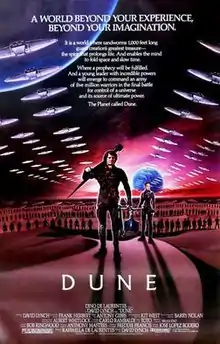

Theatrical release poster by Tom Jung | |

| Directed by | David Lynch |

| Screenplay by | David Lynch |

| Based on | Dune by Frank Herbert |

| Produced by | Raffaella De Laurentiis |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Freddie Francis |

| Edited by | Antony Gibbs |

| Music by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 137 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $40–42 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $30.9–37.9 million (North America)[2][3] |

Dune is a 1984 American epic space opera film written and directed by David Lynch and based on the 1965 Frank Herbert novel Dune. It was filmed at the Churubusco Studios in Mexico City and the soundtrack includes the rock band Toto. Its large ensemble cast includes Kyle MacLachlan's film debut as young nobleman Paul Atreides, Patrick Stewart, Brad Dourif, Dean Stockwell, Virginia Madsen, José Ferrer, Sting, Linda Hunt, and Max von Sydow.

The setting is the distant future, chronicling the conflict between rival noble families as they battle for control of the extremely harsh desert planet Arrakis, also known as Dune. The planet is the only source of the drug melange (spice), which allows prescience and is vital to space travel, making it the most essential and valuable commodity in the universe. Paul Atreides is the scion and heir of a powerful noble family, whose inheritance of control over Arrakis brings them into conflict with its former overlords, House Harkonnen. Paul is also possibly the Kwisatz Haderach, a messianic figure expected by the Bene Gesserit sisterhood.

After the novel's initial success, attempts to adapt Dune as a film began in 1971. A lengthy process of development followed throughout the 1970s, during which Arthur P. Jacobs, Alejandro Jodorowsky, and Ridley Scott unsuccessfully tried to bring their visions to the screen. In 1981, executive producer Dino De Laurentiis hired Lynch as director.

The film was a box-office bomb, grossing $30.9 million from a $40–42 million budget. At least four versions have been released worldwide. Lynch largely disowned the finished film and had his name removed or changed to pseudonyms for certain versions. The film has developed a cult following,[4][5] but opinion varies between fans of the novel and fans of Lynch's films.[6]

Plot

In the far future, the known universe is ruled by the Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV. The most valuable substance in the empire is the spice melange, which extends life and expands consciousness. The spice also allows the Spacing Guild to fold space, allowing safe, instantaneous interstellar travel. The Guild demands Shaddam clarify a conspiracy that could jeopardize spice production forever. Shaddam reveals that he has transferred power and control of the planet Arrakis, the only source of the spice, to House Atreides. However, once the Atreides arrive, they will be attacked by their archenemies, the Harkonnens, alongside Shaddam's own Sardaukar troops. Shaddam fears the Atreides due to reports of a secret army that they are amassing.

Lady Jessica, the concubine of Duke Leto Atreides, is an acolyte of the Bene Gesserit, an exclusive sisterhood with advanced physical and mental abilities. As part of a centuries-long breeding program to produce the Kwisatz Haderach, a mental "superbeing" whom the Bene Gesserit would use to their advantage, Jessica was ordered to bear a daughter but disobeyed and bore a son, Paul Atreides. Paul is tested by Reverend Mother Mohiam to assess his impulse control and, to her surprise, passes.

The Atreides leave their homeworld Caladan for Arrakis, a barren desert planet populated by gigantic sandworms. The native people of Arrakis, the Fremen, prophesy that a messiah will lead them to freedom and paradise. Duncan Idaho, one of Leto's loyalists, tells him that he suspects Arrakis holds vast numbers of Fremen who could prove to be powerful allies. Before Leto can form an alliance with the Fremen, the Harkonnens launch their attack. Leto's personal physician who is also secretly a Harkonnen double-agent, Dr. Wellington Yueh, disables the shields, leaving the Atreides defenseless. Idaho is killed, Leto is captured, and nearly all of House Atreides is wiped out by the Harkonnens. Baron Harkonnen orders Mentat Piter De Vries to kill Yueh with a poisoned blade. Leto dies in a failed attempt to assassinate the Baron using a poison-gas tooth implanted by Yueh in exchange for sparing the lives of Jessica and Paul, killing Piter instead.

Paul and Jessica survive the attack and escape into the deep desert, where they are given sanctuary by a sietch of Fremen. Paul assumes the Fremen name Muad'Dib and emerges as the messiah for whom the Fremen have been waiting. He teaches them to use Weirding Modules — sonic weapons developed by House Atreides — and targets spice mining. Over the next two years, spice production is nearly halted due to Paul’s raids. The Spacing Guild informs the Emperor of the deteriorating situation on Arrakis.

Paul falls in love with young Fremen warrior Chani. Jessica becomes the Fremen's Reverend Mother by ingesting the Water of Life, a deadly poison, which she renders harmless by using her Bene Gesserit abilities. As an after-effect of this ritual, Jessica's unborn child, Alia, later emerges from the womb with the full powers of an adult Bene Gesserit Reverend Mother. In a prophetic dream, Paul learns of the plot by the Emperor and the Guild to kill him. When Paul's dreams suddenly stop, he drinks the Water of Life and has a profound psychedelic trip in the desert. He gains powerful psychic powers and the ability to control the sandworms, which he realizes are the spice's source.

The Emperor amasses a huge invasion fleet above Arrakis to wipe out the Fremen and regain control of the planet. He has Rabban beheaded and summons the Baron to explain why spice mining has stopped. Paul launches a final attack against the Harkonnens and the Emperor's Sardaukar at Arrakeen, the capital city. Riding atop sandworms and brandishing sonic weapons, Paul's Fremen warriors easily defeat the Emperor's legions. Alia assassinates the Baron while Paul confronts the Emperor and fights Feyd-Rautha in a duel to the death. After killing Feyd, Paul demonstrates his newfound powers and fulfills the Fremen prophecy by causing rain to fall on Arrakis. Alia declares him to be the Kwisatz Haderach.

Cast

- Kyle MacLachlan as Paul Atreides, the Atreides heir

- Francesca Annis as Lady Jessica, concubine of Duke Leto and mother to Paul and Alia

- Leonardo Cimino as the Baron's Doctor[7]

- Brad Dourif as Piter De Vries, the Harkonnen Mentat

- José Ferrer as Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV

- Linda Hunt as the Shadout Mapes, the Fremen housekeeper of the Atreides' Arrakis palace

- Freddie Jones as Thufir Hawat, the Atreides Mentat

- Richard Jordan as Duncan Idaho, a Swordmaster of the Ginaz in the Atreides court

- Virginia Madsen as Princess Irulan, the Emperor's eldest daughter

- Silvana Mangano as Reverend Mother Ramallo, a Fremen woman who predicts Paul's arrival

- Everett McGill as Stilgar, the leader of the Fremen with whom Paul and Jessica take refuge

- Kenneth McMillan as Baron Vladimir Harkonnen, Duke Leto's rival

- Jack Nance as Nefud, the captain of Baron Harkonnen's guard

- Siân Phillips as Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam, the Emperor's advisor and Jessica's Bene Gesserit superior

- Jürgen Prochnow as Duke Leto Atreides, Paul's father

- Paul Smith as The Beast Rabban, Baron Harkonnen's older nephew

- Patrick Stewart as Gurney Halleck, a troubador-warrior and talented baliset musician in the Atreides court

- Sting as Feyd-Rautha, Baron Harkonnen's younger nephew

- Dean Stockwell as Doctor Wellington Yueh, the Atreides physician and unwilling traitor

- Max von Sydow as Doctor Kynes, a planetologist in the Fremen

- Alicia Witt as Alia, Paul's younger sister

- Sean Young as Chani, Paul's Fremen lover

Additionally, Honorato Magalone appears as Otheym, Judd Omen appears as Jamis, and Molly Wryn as Harah. Director David Lynch appears in an uncredited cameo as a spice worker, while Danny Corkill is shown in the onscreen credits as Orlop despite his scenes being deleted from the theatrical release.

Production

Early attempts and Jodorowsky's Dune

After the book's initial success, producers began attempting to adapt it. In mid-1971, film producer Arthur P. Jacobs optioned the film rights to Frank Herbert's 1965 novel Dune, on agreement to produce a film within nine years, but died in mid-1973, while plans for the film (including David Lean already attached to direct) were still in development.[8][9]

The film rights reverted in 1974, when the option was acquired by a French consortium led by Jean-Paul Gibon, with Alejandro Jodorowsky attached to direct.[8] Jodorowsky approached contributors including the progressive rock groups Pink Floyd and Magma for some of the music, Dan O'Bannon for the visual effects, and artists H. R. Giger, Jean Giraud, and Chris Foss for set and character design. Potential cast included Salvador Dalí as the Emperor, Orson Welles as Baron Harkonnen, Mick Jagger as Feyd-Rautha, Udo Kier as Piter De Vries, David Carradine as Leto Atreides, Jodorowsky's son Brontis Jodorowsky as Paul Atreides, and Gloria Swanson.[10] The project was ultimately canceled for several reasons, largely because funding disappeared when the project ballooned to a 10–14 hour epic.[11]

Although their film project never reached production, the work that Jodorowsky and his team put into Dune significantly impacted subsequent science-fiction films. In particular, Alien (1979), written by O'Bannon, shared much of the same creative team for the visual design as had been assembled for Jodorowsky's film. A documentary, Jodorowsky's Dune (2013), was made about Jodorowsky's failed attempt at an adaptation.[12][13]

De Laurentiis's first attempt

In late 1976, Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis purchased the rights for Dune from Gibon's consortium.[8] De Laurentiis commissioned Herbert to write a new screenplay in 1978; the script Herbert turned in was 175 pages long, the equivalent of nearly three hours of screen time.[8] De Laurentiis then hired director Ridley Scott in 1979, with Rudy Wurlitzer writing the screenplay and H. R. Giger retained from the Jodorowsky production.[8] Scott intended to split the book into two movies. He worked on three drafts of the script, using The Battle of Algiers (1966) as a point of reference, before moving on to direct another science-fiction film, Blade Runner (1982). He recalled the pre-production process was slow, and finishing the project would have been even more time-intensive:

But after seven months I dropped out of Dune, by then Rudy Wurlitzer had come up with a first-draft script, which I felt was a decent distillation of Frank Herbert's [book]. But I also realized Dune was going to take a lot more work—at least two and a half years' worth. And I didn't have the heart to attack that because my [older] brother Frank unexpectedly died of cancer while I was prepping the De Laurentiis picture. Frankly, that freaked me out. So, I went to Dino and told him the Dune script was his.

- —From Ridley Scott: The Making of His Movies by Paul M. Sammon[9]

Lynch's screenplay and direction

In 1981, the nine-year film rights were set to expire. De Laurentiis renegotiated the rights from the author, adding to them the rights to the Dune sequels, written and unwritten.[8] He then showed the book to Sid Sheinberg, president of MCA, the parent company of Universal City Studios, which approved the book. After seeing The Elephant Man (1980), producer Raffaella De Laurentiis decided that David Lynch should direct the movie. Around that time, Lynch received several other directing offers, including Return of the Jedi. De Laurentiis contacted Lynch, who said he had not heard of the book. After reading it and "loving it", he met with De Laurentiis and agreed to direct the film.[14][15] Lynch worked on the script for six months with Eric Bergren and Christopher De Vore. The team yielded two drafts of the script and split over creative differences. Lynch then worked on five more drafts. Initially, Lynch had scripted Dune across two films, but eventually was condensed into a single film.[8]

Virginia Madsen said in 2016 that she was signed for three films, as the producers "thought they were going to make Star Wars for grown-ups."[16]

On March 30, 1983, with the 135-page sixth draft of the script, Dune finally began shooting. It was shot entirely in Mexico, mostly at Churubusco Studios; De Laurentiis said this was due in part to the favorable exchange rate to get more value for their production budget, and that no studio in Europe had the expansive capabilities they needed for the production. With a budget over $40–42 million, Dune required 80 sets built on 16 sound stages, and had a total crew of 1,700, with over 20,000 extras. Many of the exterior shots were filmed in the Samalayuca Dune Fields in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua.[8][17][18] Filming ran for at least six months into September 1983, plagued by various production problems such as failing electricity or communication lines due to the country's infrastructure, or health-related problems with their cast and crew.[8]

Editing

The rough cut of Dune without post-production effects ran over four hours long, but Lynch's intended cut of the film (as reflected in the seventh and final draft of the script) was almost three hours long. Universal and the film's financiers expected a standard, two-hour cut of the film. Dino De Laurentiis, his daughter Raffaella, and Lynch excised numerous scenes, filmed new scenes that simplified or concentrated plot elements, and added voice-over narrations, plus a new introduction by Virginia Madsen. Contrary to rumor, Lynch made no other version than the theatrical cut.

Versions

A television version was aired in 1988 in two parts totaling 186 minutes; it replaced Madsen's opening monologue with a much longer description of the setting that used concept art stills. Lynch disavowed this version and had his name removed from the credits. Alan Smithee was credited, a pseudonym used by directors who wish to disavow a film. The extended and television versions additionally credit writer Lynch as Judas Booth. This version (without recap and second credit roll) has previously been released on DVD as Dune: Extended Edition.

Several longer versions have been spliced together, particularly for two other versions, one for San Francisco station KTVU, and the other a 178-minute fan edit from scratch by SpiceDiver. The latter cut was officially released by Koch Films (on behalf of current international rights holder Lionsgate) on a deluxe 4K/Blu-ray box set released in Germany in 2021. The KTVU and SpiceDiver versions combine footage from the theatrical and television versions, and downplay the repeated footage in the TV cut.[19]

Although Universal has approached Lynch for a possible director's cut, Lynch has declined every offer and prefers not to discuss Dune in interviews.[20] In 2022, though, during an interview about the remaster of his film Inland Empire (2006), he admitted to the surprised interviewer that he was interested in the idea. He offered the caveat that he did not believe it would ever happen, nor that anything in the unused footage would satisfy him enough for a director's cut, as he said he was "selling out" during production. Nevertheless, he said enough time had passed that he was at least curious to take another look at the footage.[21]

Canceled sequels

When production started, it was anticipated for the film to launch a Dune franchise, and plans had been made to film two sequels back-to-back. Many of the props were put into storage after the completion of production in anticipation of future use, MacLachlan had signed for a two-film deal, and Lynch had begun writing a screenplay for the second film. Once Dune was released and failed at the box office, the sequel plans were canceled.

In July 2023, writer Max Evry, doing research for his book, A Masterpiece in Disarray: David Lynch's Dune, on the first film's influence, discovered Lynch's half-completed draft treatment for the second film at the Frank Herbert Archives at California State University. Lynch was reached for comment in January 2024 and responded through representative that he recalled beginning work on a script, but much like the first film, did not want to comment further. Based partly on Dune Messiah, Emry described the tentatively-titled Dune II as having surpassed the novel's narrative approach in the screenplay adaption.[7]

Release

Marketing

Dune premiered in Washington, DC, on December 3, 1984, at the Kennedy Center and was released worldwide on December 14. Prerelease publicity was extensive, because it was based on a bestselling novel, and because it was directed by Lynch, who had had success with Eraserhead and The Elephant Man. Several magazines followed the production and published articles praising the film before its release,[22] all part of the advertising and merchandising of Dune, which also included a documentary for television, and items placed in toy stores.[23]

Home media

The film was released on Ultra HD Blu-ray by Arrow Films in North America and the United Kingdom on August 31, 2021, a few weeks ahead of the release of Dune, the 2021 film adaptation of the book.[24] This release only contains the theatrical cut of the film, because Universal has removed it from circulation in North America after attempts by Arrow to license the television version.

Koch Films has also released a more definitive multi-disc edition (available only in Germany) containing three of the four versions—theatrical, TV, and SpiceDiver fan edits—plus supplemental materials (some not available on the Arrow release) and the CD soundtrack.

Reception

Box office

The film opened on December 14, 1984, in 915 theaters, and earned US$6,025,091 in its opening weekend, ranking number two in the domestic box office behind Beverly Hills Cop.[25] By the end of its run, Dune had grossed $30,925,690 (equivalent to $87,000,000 in 2022).[2] On an estimated production budget of $40–42 million, the film was considered a box-office disappointment.[26] The film later had more success, and has been called the "Heaven's Gate of science fiction".[27]

Critical response

Dune received mostly negative reviews upon release. Roger Ebert gave one star out of four, and wrote, "This movie is a real mess, an incomprehensible, ugly, unstructured, pointless excursion into the murkier realms of one of the most confusing screenplays of all time."[28] Ebert added: "The movie's plot will no doubt mean more to people who've read Herbert than to those who are walking in cold",[28] and later named it "the worst movie of the year".[29] On At the Movies with Gene Siskel and Ebert, Siskel began his review by saying "it's physically ugly, it contains at least a dozen gory gross-out scenes, some of its special effects are cheap—surprisingly cheap because this film cost a reported $40–45 million—and its story is confusing beyond belief. In case I haven't made myself clear, I hated watching this film."[30] The film was later listed as the worst film of 1984 and the "biggest disappointment of the year" in their "Stinkers of 1984" episode.[31] Other negative reviews focused on the same issues and on the length of the film.[32]

Janet Maslin of The New York Times gave Dune a negative review of one star out of five. She said, "Several of the characters in Dune are psychic, which puts them in the unique position of being able to understand what goes on in the movie" and explained that the plot was "perilously overloaded, as is virtually everything else about it".[33]

Variety gave Dune a less negative review, stating "Dune is a huge, hollow, imaginative, and cold sci-fi epic. Visually unique and teeming with incident, David Lynch's film holds the interest due to its abundant surface attractions, but won't, of its own accord, create the sort of fanaticism which has made Frank Herbert's 1965 novel one of the all-time favorites in its genre." They also commented on how "Lynch's adaptation covers the entire span of the novel, but simply setting up the various worlds, characters, intrigues, and forces at work requires more than a half-hour of expository screen time." They did enjoy the cast and said, "Francesca Annis and Jürgen Prochnow make an outstandingly attractive royal couple, Siân Phillips has some mesmerizing moments as a powerful witch, Brad Dourif is effectively loony, and best of all is Kenneth McMillan, whose face is covered with grotesque growths and who floats around like the Blue Meanie come to life."[34]

Richard Corliss of Time gave Dune a negative review, stating, "Most sci-fi movies offer escape, a holiday from homework, but Dune is as difficult as a final exam. You have to cram for it. [...] MacLachlan, 25, grows impressively in the role; his features, soft and spoiled at the beginning, take on a he-manly glamour once he assumes his mission. [...] The actors seem hypnotized by the spell Lynch has woven around them—especially the lustrous Francesca Annis, as Paul's mother, who whispers her lines with the urgency of erotic revelation. In those moments when Annis is onscreen, Dune finds the emotional center that has eluded it in its parade of rococo decor and austere special effects. She reminds us of what movies can achieve when they have a heart, as well as a mind."[35]

Film scholar Robin Wood called Dune "the most obscenely homophobic film I have ever seen"[36]—referring to a scene in which Baron Harkonnen sexually assaults and kills a young man by bleeding him to death—charging it with "managing to associate with homosexuality in a single scene physical grossness, moral depravity, violence, and disease".[36] Dennis Altman suggested that the film showed how "AIDS references began penetrating popular culture" in the 1980s, asking, "Was it just an accident that in the film Dune the homosexual villain had suppurating sores on his face?"[37]

Critic and science-fiction writer Harlan Ellison reviewed the film positively. In his 1989 book of film criticism, Harlan Ellison's Watching, he says that because critics were denied screenings at the last minute after several reschedules, it made the film community feel nervous and negative towards Dune before its release.[38] Ellison later said, "It was a book that shouldn't have been shot. It was a script that couldn't have been written. It was a directorial job that was beyond anyone's doing ... and yet the film was made."[39] Daniel Snyder also praised elements of the film in a 2014 article which called the movie "a deeply flawed work that failed as a commercial enterprise, but still managed to capture and distill essential portions of one of science fiction's densest works." Snyder stated that Lynch's "surreal style" created "a world that felt utterly alien [full of] bizarre dream sequences, rife with images of unborn fetuses and shimmering energies, and unsettling scenery like the industrial hell of the Harkonnen homeworld, [making] the fil[m] actually closer to Kubrick (2001: A Space Odyssey) than [George] Lucas. It seeks to put the viewer somewhere unfamiliar while hinting at a greater, hidden story." Snyder praised the production and stated that Herbert had said he was pleased with Lynch's film.[5]

Colin Greenland reviewed Dune for Imagine magazine, and stated, "Anthony Masters's magnificent design features none of the gleaming chrome and sterile plastic we expect of space opera: instead, sinister paraphernalia of cast iron and coiled brass, corridors of dark wood and marble, and the sand, the endless sand..."[40]

Science-fiction historian John Clute argued that though Lynch's Dune "spared nothing to achieve its striking visual effects", the film adaptation "unfortunately—perhaps inevitably—reduced Herbert's dense text to a melodrama".[41]

The few more favorable reviews praised Lynch's noir-baroque approach to the film. Others compare it to other Lynch films that are equally inaccessible, such as Eraserhead, and assert that to watch it, the viewer must first be aware of the Dune universe. In the years since its initial release, Dune has gained more positive reviews from online critics[42] and viewers.[43] On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 44% based on 77 reviews, with an average score of 5.6/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "This truncated adaptation of Frank Herbert's sci-fi masterwork is too dry to work as grand entertainment, but David Lynch's flair for the surreal gives it some spice."[42] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 41 out of 100 based on 20 critic reviews, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[44]

As a result of its poor commercial and critical reception, all initial plans for Dune sequels were canceled. David Lynch reportedly was working on the screenplay for Dune Messiah[45] and was hired to direct both proposed second and third Dune films. Lynch later said:

I started selling out on Dune. Looking back, it's no one's fault but my own. I probably shouldn't have done that picture, but I saw tons and tons of possibilities for things I loved, and this was the structure to do them in. There was so much room to create a world. But I got strong indications from Raffaella and Dino De Laurentiis of what kind of film they expected, and I knew I didn't have final cut.[46]

In the introduction for his 1985 short story collection Eye, author Frank Herbert discussed the film's reception and his participation in the production, complimented Lynch, and listed scenes that were shot but left out of the released version. He wrote, "I enjoyed the film even as a cut and I told it as I saw it: What reached the screen is a visual feast that begins as Dune begins and you hear my dialogue all through it. [...] I have my quibbles about the film, of course. Paul was a man playing god, not a god who could make it rain."[47]

Alejandro Jodorowsky, who had earlier been disappointed by the collapse of his own attempt to film Dune, later said he had been disappointed and jealous when he learned Lynch was making Dune, as he believed Lynch was the only other director capable of doing justice to the novel. At first, Jodorowsky refused to see Lynch's film, but his sons coerced him. As the film unfolded, Jodorowsky says he became very happy, seeing that it was a "failure", but that this was certainly the producers' fault and not Lynch's.[48]

Accolades

Dune was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Sound (Bill Varney, Steve Maslow, Kevin O'Connell, and Nelson Stoll).[49]

The film won a 1984 Stinkers Bad Movie Awards for Worst Picture.[50]

Tie-in media

Novelization

An illustrated junior novelization, commonly published for movies during the 1970s and 1980s, is titled The Dune Storybook.[51]

Toys

A line of Dune action figures from toy company LJN was released to lackluster sales in 1984. Styled after Lynch's film, the collection includes figures of Paul Atreides, Baron Harkonnen, Feyd-Rautha, Glossu Rabban, Stilgar, and a Sardaukar warrior, plus a poseable sandworm, several vehicles, weapons, and a set of View-Master stereoscope reels. Figures of Gurney and Lady Jessica previewed in LJN's catalog were never produced.[52][53] In 2006, SOTA Toys produced a Baron Harkonnen action figure for their "Now Playing Presents" line.[53] In October 2019, Funko started a "Dune Classic" line of POP! vinyl figures, the first of which was Paul in a stillsuit and Feyd in a blue jumpsuit, styled after the 1984 film.[54][55] An alternate version of Feyd in his blue loincloth was released for the 2019 New York Comic Con.[56]

Games

Several Dune games have been styled after Lynch's film. Parker Brothers released the board game Dune in 1984,[57] and a 1997 collectible card game called Dune[58] was followed by the role-playing game Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium in 2000.[59][60] The first licensed Dune video game is Dune (1992) from Cryo Interactive/Virgin Interactive.[61][62] Its successor, Westwood Studios's Dune II (1992), is generally credited for popularizing and setting the template for the real-time strategy genre of PC games.[63][64] This game was followed by Dune 2000 (1998), a remake of Dune II from Intelligent Games/Westwood Studios/Virgin Interactive.[65] Its sequel is the 3D video game Emperor: Battle for Dune (2001) by Intelligent Games/Westwood Studios/Electronic Arts.[66][67]

Comics

Marvel Comics published an adaptation of the movie written by Ralph Macchio and illustrated by Bill Sienkiewicz.[68]

Notes

- ↑ The end credits states "Prophecy Theme" was composed by Brian Eno, Daniel Lanois, and Roger Eno.

References

- ↑ "Dune (PG) (Cut)". British Board of Film Classification. November 20, 1984. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Dune (1984)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- 1 2 Knoedelseder, William K. Jr. (August 30, 1987). "De Laurentiis: Producer's Picture Darkens". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 28, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ↑ Schilling, Dave (October 24, 2021). "David Lynch's Dune bombed, but was actually foundational". Polygon. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- 1 2 Snyder, Daniel D. (March 14, 2014). "The Messy, Misunderstood Glory of David Lynch's Dune". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- ↑ Schedeen, Jesse (October 21, 2021). "Dune Movie Explained: What to Know About the Classic Sci-Fi Novel". IGN. Archived from the original on April 20, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- 1 2 Evry, Max (January 10, 2024). "I Found David Lynch's Lost Dune II Script". Wired. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Harmetz, Aljean (September 4, 1983). "The World Of 'Dune' Is Filmed In Mexico". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 1, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- 1 2 "Dune: Book to Screen Timeline". DuneInfo. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ↑ Jodorowsky, Alejandro (1985). "Dune: Le Film Que Voue Ne Verrez Jamais" [Dune: The Film You Will Never See]. Métal hurlant. No. 107. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved February 8, 2014 – via DuneInfo.

- ↑ Frank Pavich (director) (2013). Jodorowsky's Dune (Documentary).

- ↑ Keslassy, Elsa (April 23, 2013). "U.S. Fare Looms Large in Directors' Fortnight". Variety. Archived from the original on April 26, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ↑ "Sony Classics Acquires Cannes Docu Jodorowsky's Dune". Deadline Hollywood. July 11, 2013. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ↑ Sammon, Paul M. (September 1984). "David Lynch's Dune". Cinefantastique. Vol. 14, no. 4/5. p. 31.

- ↑ David Lynch Interview from 1985 on Dune. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ↑ Virginia Madsen on Dune. DuneInfo. September 11, 2016. Archived from the original on April 24, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2018 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Emilio Ruiz del Río". DuneInfo. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Samalayuca Dunes declared natural protected zone". Chihuahuan Frontier. June 9, 2009. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ↑ Murphy, Sean (1996). "Building the Perfect Dune". Video Watchdog. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ↑ "Dune Resurrection – Re-visiting Arrakis". DuneInfo. Archived from the original on May 2, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ↑ Simon, Brent (April 15, 2022). "David Lynch on remastering Inland Empire, revisiting his earlier work and the chances of a Dune do-over". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on April 16, 2022. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ↑ Strasser, Brendan (1984). "David Lynch reveals his battle tactics". Prevue. Archived from the original on January 8, 2006. Retrieved January 18, 2013 – via TheCityofAbsurdity.com.

- ↑ "The Dune Collectors Survival Guide". Arrakis.co.uk. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ↑ Bonifacic, Igor (May 31, 2021). "David Lynch's 'Dune' will be released on 4K Blu-ray in August". Engadget. Archived from the original on June 1, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ↑ "Weekend Box Office Results for December 14–16, 1984". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Revenge of the epic movie flops". The Independent. April 12, 2010. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ↑ Wiseman, Andreas (September 1, 2021). "'Dune' 1984: Francesca Annis, The Original Lady Jessica, Lifts The Lid On Life Behind The Scenes Of David Lynch's Epic, The 'Heaven's Gate' Of Sci-Fi". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- 1 2 Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1984). "Movie Reviews: Dune (1984)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on December 20, 2009. Retrieved September 30, 2020 – via RogerEbert.SunTimes.com.

- ↑ Cullum, Brett (February 13, 2006). "Review: Dune: Extended Edition". DVD Verdict. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ↑ "Dune". At The Movies. December 1984.

- ↑ "The Stinkers of 1984". At The Movies. January 5, 1985.

- ↑ "Dune: Retrospective". Extrovert. 2006. p. 6. Archived from the original on February 4, 2006. Retrieved March 20, 2019 – via Extrovertmagazine.com.

- ↑ Maslin, Janet (December 14, 1984). "Movie Review: Dune (1984)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Movie Review: Dune". Variety. December 31, 1983. Archived from the original on February 21, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ↑ Corliss, Richard (December 17, 1984). "Cinema: The Fantasy Film as Final Exam". Time. Archived from the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- 1 2 Wood, Robin (1986). Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan. Columbia University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-231-05777-6.

- ↑ Altman, Dennis (1986). AIDS and the New Puritanism. London: Pluto Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-7453-0012-X.

- ↑ Lafrance, J.D. (September 2005). "Dune: Its name is a Killing Word". Erasing Clouds. No. 38. Archived from the original on April 15, 2011. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Looking Back at All the Utterly Disastrous Attempts to Adapt Dune". Vulture. March 9, 2017. Archived from the original on April 21, 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- ↑ Greenland, Colin (March 1985). "Fantasy Media". Imagine (review). TSR Hobbies (UK), Ltd. (24): 47.

- ↑ Clute, John (1996). Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia. New York: Dorling Kindersley. p. 282. ISBN 0-7894-0185-1.

- 1 2 "Dune". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on December 28, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Dune (1984)". Yahoo! Movies. April 20, 2011. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Dune (1984) Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Visionary and dreamer: A surrealist's fantasies". Cinema. No. 12. 1984. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved January 18, 2013 – via DavidLynch.de.

- ↑ "Star Wars Origins: Dune". Moongadget.com. Archived from the original on December 13, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ↑ Herbert, Frank (1985). "Introduction". Eye. ISBN 0-425-08398-5.

- ↑ Alejando Jodorowsky's interview in the documentary Jodorowsky's Dune, 2014.

- ↑ "The 57th Academy Awards (1985) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org. Archived from the original on December 28, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ↑ "1984 7th Hastings Bad Cinema Society Stinkers Awards". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 17, 2006. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ↑ Vinge, Joan (1984). The Dune storybook. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-399-12949-0. OCLC 1033568950 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Daniels, James (January 12, 2014). "Toys We Miss: Dune". Nerd Bastards. Archived from the original on January 27, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- 1 2 "Toys". Collectors of Dune. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ↑ Murphy, Tyler (October 20, 2019). "Funko Adds Dune to its Pop! Line-up". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ↑ Little, Jesse (October 18, 2019). "Coming Soon: Pop! Movies – Dune Classic!". Funko. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ↑ Little, Jesse (September 4, 2019). "2019 NYCC Exclusive Reveals: Dune!". Funko. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ↑ "Dune (1984)". BoardGameGeek. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ↑ Baumrucker, Steven (May 2003). "Dune – Classic CCG". Scrye. Archived from the original on May 3, 2004. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ↑ Guder, Derek (April 19, 2001). "Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium Capsule Review". RPG.net. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ↑ Valterra, Anthony (2000). "D20 Product News: Dune". Wizards.com. Archived from the original on January 24, 2001. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ↑ "Game Overview: Dune (1992)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on January 11, 2010. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ↑ Kosta. "Review: Dune (1992)". Abandonia.com. Archived from the original on May 14, 2010. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ↑ Bates, Bob (2003). Game Developer's Market Guide. Thomson Course Technology. p. 141. ISBN 1-59200-104-1.

- ↑ Geryk, Bruce (May 19, 2008). "A History of Real-Time Strategy Games: Dune II". GameSpot. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Game Overview: Dune 2000 (1998)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ↑ "Game Overview: Emperor: Battle for Dune (2001)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on January 10, 2010. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ↑ Alam, Mohammad Junaid. "Review: Emperor: Battle for Dune (2001)". Guru3D.com. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ↑ "Marvel Comic of Dune". Archived from the original on March 2, 2003.

External links

- Official website

- Dune at IMDb

- Dune at AllMovie

- Dune at Box Office Mojo

- Dune at the TCM Movie Database

- Dune at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Dune at The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

- "Dune: THR's 1984 Review". The Hollywood Reporter. December 14, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Lofficier, Randy; Lofficier, Jean-Marc (November 1984). "Raffaella De Laurentiis: The Mastermind of Dune". Starlog. No. 88. pp. 25–28. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- 2012 interview with Kyle MacLachlan about Dune and Blue Velvet

- Dune. 1984. OCLC 1295459964.