Early glassmaking in the United States, covered herein as before the 18th century (or through 1700), began before the country existed. The glassmaking began in 1608 at the Colony of Virginia near Jamestown. The 1608 glass factory is believed to be the first industrial facility in what became the United States. Skilled Polish and German (described as "Dutchmen") workers were brought to the colony to begin the glassmaking. Although glass was made at Jamestown, production was soon suspended because of strife in the colony. A second attempt at Jamestown also failed.

Other attempts to produce glass were made during the 1600s, and a few had some success. Glass works in New Amsterdam and the Colony of Massachusetts Bay are often mentioned by historians. Much of the evidence concerning the 17th century New Amsterdam glass factories has been lost, and the Massachusetts glassworks did not last long. More glassmaking began in the 18th century, but by 1800 it is thought that there were only about ten glass works producing in the United States.

Glassmaking

Glass is made by starting with a batch of ingredients, melting it together, forming the glass product, and gradually cooling it. The batch of ingredients is dominated by sand, which contains silica. Smaller quantities of other ingredients, such as soda and limestone, are also added to the batch.[1] The batch is placed inside a pot or tank that is heated by a furnace to roughly 3,090 °F (1,700 °C).[2][Note 1] Glassmakers use the term "metal" to describe batch that has been melted together.[5]

The melted batch, or metal, is typically shaped into the glass product (other than plate and window glass) by either glassblowing or pressing it into a mold.[6] Glass was not pressed in the United States until the 1820s.[7] Window glass production, until the 20th century, involved blowing a cylinder and flattening it.[8] The Crown method and the Cylinder method were the major methods used to make window glass until the process was changed dramatically in the 1920s.[9] All glass products must then be cooled gradually (annealed), or else they could easily break.[10] Annealing was originally conducted in the United States using a kiln that was sealed with the fresh glass inside, heated, and gradually cooled.[11] In the United States during the 1860s annealing kilns were replaced with a conveyer oven, called a lehr, that was less labor intensive.[12] Until the 1760s, most glass produced in what would become the United States was "green" glass, which has a greenish color and does not contain any additives to remove the greenish tint or add a more pleasing color.[13]

One of the major expenses for the glass factories is fuel for the furnace, and this often determined the location of the glass works.[14] Wood was the original fuel used by glassmakers in the United States. Coal began being used in the United States in the 1790s.[15] Alternative fuels such as natural gas and oil were not used in the United States until 1875.[16] Other important aspects of glassmaking are labor and transportation.[17] Glassmaking methods and recipes were kept secret, and most European countries forbid immigration to the United States by glassworkers.[18] Some of the skilled glassworkers were smuggled from Europe to the United States.[18] Waterways provided transportation networks before the construction of highways and railroads.[19] The first railroad in the United States was not chartered until 1827, and construction began in 1828.[20]

English colonies

Jamestown

England established Jamestown in its Colony of Virginia during May 1607.[21] Slightly over one year later, an attempt was made at this North American colony to produce glass.[22] Glassmaking was not thriving in England at the time because the use of wood as fuel for the glassmaking furnaces was discouraged and eventually prohibited. Furnaces using coal for fuel were still in early stages of development. England was dependent on Venice and other cities in Europe for the fulfillment of its glass needs. Because North America appeared to have a massive number of forests, it was viewed as having potential for glassmaking.[22] The Virginia Company of London sent supplies to Jamestown that arrived during October 1608. Arriving with the supplies were eight men with manufacturing skills, including glassmaking. The men were said to be "Dutch" and Polish, although the Dutch men were probably German—and are identified as German by most historians.[23][Note 2] Captain John Smith's writing (sometimes with questionable spelling) discussed the difficulties of making glass in the colony. Part of his writing began with "As for the hyring of the Poles and Dutch men...", but later stated that it was useless "to send to Germany or Poleland for glasse–men...."[26]

The site of the Jamestown glass works was described by Captain John Smith and mentioned by writer William Strachey.[27] Ruins were discovered in 1931, leading to the belief that the Jamestown glass works was located about one mile (1.6 km) from Jamestown at a place now known as Glass House Point.[28] Some structural and artifact evidence had been discovered in the 1920s.[29] Glass products have been speculated to be bottles or beads, but "conclusive proof has not been advanced".[30] Glassmaking began shortly after the glassworkers arrived, and the supply ship carried sample glassware on its return voyage.[21] In the spring of 1609, a "tryall of glasse" was produced.[31] It is believed that production of glass ended during the difficult winter of 1609–1610, a period known as the Starving Time.[31] Although this attempt to produce glass cannot be called a long–term success, it can be concluded that glass was first produced in Jamestown during the Fall of 1608, the first American glass factory was located at Jamestown, and this was the first industrial production by the English in North America.[32][Note 3]

During 1621, plans were made to revive glassmaking at Jamestown. The plan was for beads and "drinckinge Glasse" products to be produced by four Italian men who would come to Jamestown with their families.[34] The glassworkers sailed for Jamestown in late August 1621. A glass house was constructed, but the Massacre of 1622 and sickness delayed progress. No glass had been produced by June 1622.[35] There is no evidence of the exact location of the glassworks used in 1622, and no definitive evidence of the glass product made. Beads were definitely traded with the local Native Americans, so it is possible that glass beads were the product made.[36] There is evidence that the furnace was working during March 1623, but problems with the quality of sand caused output during March 1623 to be described as "nothing".[37] After the winter of 1623–1624, the glass works became inactive. In April 1625 it was decided to end the glassmaking project.[38] Causes of the failure were inadequate security, food supply, quality of sand, and disagreement among supervisors and glass workers.[39] Although glass was produced at Jamestown, longer term success did not happen in 1608 or in a second attempt in the 1620s.[22] Today (2015), the National Park Service exhibits the Jamestown furnace ruins at Glasshouse Point, and glassmakers in a nearby reconstructed glasshouse produce glass objects using the 17th century methods.[40]

Northern colonies

Well north of Jamestown was the Colony of Massachusetts Bay. In 1639 Obadiah Holmes and Lawrence Southwick formed a partnership to start a glassmaking facility. A year later they were joined by a glassman named Ananias Concklin, and they received funding from the town of Salem, Massachusetts, in 1641.[41] A Southwick family descendant has said that "hollow ware and bottles" were made at the glass works in "light green, dark green, blue and brown glass."[42] The family member also said that "bulls eyes for windows and doors" were made, meaning that the Crown method for making window glass was used.[43] Some historians believe the works operated sporadically until 1661, while others believe it shut down in 1642 or 1643.[44]

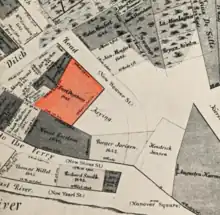

During the 1620s the Dutch colony in North America had a trading post, named New Amsterdam, that was located in what is now the lower part of Manhattan in New York City.[45] A glassmaking facility was established by Everett Duijcking (also spelled Evert Duycking or Evert Duyckingk) around 1645.[46] Duijcking was a German from Westphalia, although his native town was close to the border with the Netherlands.[47] Jacob Milyer (also spelled Melyer) took over this glass works in 1674.[46] The Melyer family is believed to have continued making glass into the third and fourth generations, leading one to deduct that, if true, glass may have been made at this glass works in Manhattan from 1645 to about 1767.[48]

Another New Amsterdam glassmaker was Johannes Smedes (also known as "Jan"), who received a portion of land in 1654 adjacent to what became known locally as "Glass–makers Street".[49][Note 4] In 1664, the same year Dutch occupation ended, he sold his glass works and moved to Long Island.[51] His products were believed to be window glass, bottles, and house wares.[46] Other glassmakers in the New Amsterdam–New York area included Routoff Jansen and Cornelius Dirkson, who first sharpened their skills working for Smedes.[52]

During the early 1680s the Free Society of Traders built a glass factory close to Philadelphia in the Province of Pennsylvania. The works was managed by Joshua Tittery, who was also a potter.[53] The works was located at Frankford.[54] Bottles and window panes were made for several years under the guidance of English glass blowers.[55] The glass making was not a productive endeavor, and Tittery had more success producing pottery.[56] A letter written to Penn in 1684 says the "Glasshouse comes to nothing".[57] Pressure from investors caused glassmaking to be abandoned in 1685.[58][Note 5]

Future glassmaking

Over one dozen glass works operated in the United States (or what would become the United States) during the 18th century, as several milestones were achieved.[60] In the Province of New Jersey, German–immigrant Caspar Wistar's glass works was the first to achieve large–scale long–term success.[61] Another German immigrant, Henry William Stiegel, was the first in America to make fine lead crystal, which is often mislabeled as flint glass.[62] A third German immigrant, John Frederick Amelung, invested more money in glassmaking than anyone ever had and produced impressive quality glass with engraving—but his business failed after 11 years.[63]

From its beginning, American glassmakers used wood as the fuel for their furnaces that melted the raw ingredients for glass. Philadelphia's Kensington Glass Works, around 1771, may have been the first American glass plant to use coal to power its furnace.[64] In the 1790s, the O'Hara and Craig glass works was the first glass works in Pittsburg, and this works was another early user of coal as a fuel for its furnaces.[65] By 1800, it is thought that roughly ten glass works were operating in the United States.[66]

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ An older source states that the batch melting temperature is 2,600 °F (1,430 °C).[3] Another older source quotes a glass works spokesman as saying the furnace is heated to between 2,800 °F (1,540 °C) and 3,600 °F (1,980 °C).[4]

- ↑ The term that native Germans use to describe themselves is "Deutche", and this may have caused confusion between "Dutch" and "Deutche". An example of this misconception is the term "Pennsylvania Dutch", which actually refers to a group of people who came from a German–speaking region of Europe.[24] In 1916, it was thought that in the United States "nine out of ten speak of a Dutchman when a German is meant".[25]

- ↑ Glassmaking was conducted in Spanish colonial Mexico, in Puebla, during the 1530s.[33]

- ↑ Smedes has also been spelled as "Smeedes".[50]

- ↑ An older source, Knittle, calls this works the "Chester Creek Glass Works". She states that the works was built in Delaware County, managed by Tittery, and already abandoned by 1685.[59]

Citations

- ↑ "How Glass is Made – What is glass made of? The wonders of glass all come down to melting sand". Corning. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.; Shotwell 2002, pp. 32–33

- ↑ "How Glass is Made – What is glass made of? The wonders of glass all come down to melting sand". Corning. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ↑ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 60

- ↑ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 35

- ↑ Shotwell 2002, p. 343

- ↑ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 41-42

- ↑ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 58

- ↑ Kutilek 2019, pp. 37–41

- ↑ Shotwell 2002, pp. 110, 124–125

- ↑ "Corning Museum of Glass – Annealing Glass". Corning Museum of Glass. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ↑ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 48

- ↑ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 48; "Corning Museum of Glass – Lehr". Corning Museum of Glass. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ↑ Purvis 1999, p. 107; Shotwell 2002, p. 224

- ↑ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, pp. 12–13

- ↑ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 13

- ↑ Skrabec 2007, p. 74

- ↑ Skrabec 2007, pp. 96–97

- 1 2 Skrabec 2011, p. 20

- ↑ Poor 1868, p. 11

- ↑ Poor 1868, p. 14

- 1 2 Hatch 1941, p. 119

- 1 2 3 Lanmon & Palmer 1976, p. 14

- ↑ Hatch 1941, p. 119; "The Dream of Exporting Glass". Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation. Archived from the original on November 9, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2023.; "Glassmaking at Jamestown". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on November 9, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2023.; Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 77

- ↑ "Pennsylvania Dutch Crafts and Culture" (PDF). National Council for the Social Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 15, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ Baker 1913, p. 27

- ↑ Hatch 1941, pp. 127–128; "Glassmaking at Jamestown". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on November 9, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ Hatch 1941, pp. 120–121

- ↑ Hatch 1941, pp. 121–122

- ↑ Cotter 1958, p. 100

- ↑ Hatch 1941, p. 126

- 1 2 Hatch 1941, p. 127

- ↑ Hatch 1941, pp. 119–120; Tillotson 1920, p. 354

- ↑ Alexander 2019, p. 89

- ↑ Hatch 1941, pp. 130–131

- ↑ Hatch 1941, p. 134-136

- ↑ Hatch 1941a, pp. 229–231

- ↑ Hatch 1941, p. 137

- ↑ Hatch 1941a, p. 227

- ↑ Hatch 1941a, p. 228

- ↑ "Historic Jamestowne - Glassmaking at Jamestown". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ Knittle 1927, p. 64

- ↑ Hunter 1914, p. 139

- ↑ Hunter 1914, p. 139; Shotwell 2002, pp. 60, 110

- ↑ Knittle 1927, p. 65; Purvis 1999, p. 107; Hunter 1914, p. 139

- ↑ Knittle 1927, p. 67

- 1 2 3 Shotwell 2002, p. 376

- ↑ Hunter 1914, p. 141

- ↑ Knittle 1927, p. 74

- ↑ Knittle 1927, pp. 68–69

- ↑ Hunter 1914, p. 140

- ↑ Knittle 1927, p. 69

- ↑ Knittle 1927, pp. 69–70

- ↑ Gillingham 1930, p. 98

- ↑ Hommel 1947, p. 24

- ↑ Palmer 1979, p. 104

- ↑ Gillingham 1930, pp. 100–102

- ↑ Nash 1965, pp. 166–167

- ↑ Nash 1965, p. 168

- ↑ Knittle 1927, p. 75

- ↑ McKearin & McKearin 1966, p. 78

- ↑ "Find Rum Evidence from 18th Century". Midland Journal (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). September 10, 1920. Archived from the original on 2023-11-13. Retrieved 2023-11-13.; Zerwick 1990, p. 71; "1989 The Wistars and their Glass 1739 – 1777". Wheaton Arts and Cultural Center. Archived from the original on November 13, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.; McKearin & McKearin 1966, p. 78; Knittle 1927, pp. 94–95

- ↑ Palmer 1979, p. 107; Hunter 1914, p. 70; Shotwell 2002, p. 343

- ↑ Zerwick 1990, p. 72

- ↑ Palmer 1979, p. 107

- ↑ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 83

- ↑ Dyer & Gross 2001, p. 23

Bibliography

- Alexander, Rani (2019). Technology and Tradition in Mesoamerica after the Spanish Invasion ... Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-82636-015-1. OCLC 1057243820.

- Baker, Josephine Turck, ed. (February 1913). "Holland Dutch". Correct English – How to Use It. Evanston, Illinois: Correct English Publishing Company. 12 (2): 27. OCLC 1774694. Archived from the original on November 8, 2023. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- Cotter, John L. (1958). "Archeological Excavations at Jamestown". Archeological Research Series. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior (4): 1–299. OCLC 1118452. Archived from the original on November 3, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- Dyer, Davis; Gross, Daniel (2001). The Generations of Corning: The Life and Times of a Global Corporation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19514-095-8. OCLC 45437326.

- Gillingham, Harrold E. (1930). "Pottery, China, and Glass Making in Philadelphia". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. LIV (2): 97–129. JSTOR 20086733. Archived from the original on December 4, 2023. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- Hatch, Charles E. (April 1941). "Glassmaking in Virginia, 1607–1625". The William and Mary Quarterly. 21 (2): 119–138. JSTOR 1923625. Archived from the original on October 27, 2023. Retrieved October 27, 2023.

- Hatch, Charles E. (July 1941a). "Glassmaking in Virginia, 1607–1625 (Second Installment)". The William and Mary Quarterly. 21 (3): 227–238. JSTOR 1919822. Archived from the original on November 2, 2023. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- Hommel, Rudolph P. (October 1947). "Hilltown Glass Works (A Preliminary Report)" (PDF). The Bulletin of the Historical Society of Montgomery County. VI (1): 24–28. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 21, 2023. Retrieved December 14, 2023.

- Hunter, Frederick William (1914). Steigel Glass. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Co. OCLC 1383707. Archived from the original on December 4, 2023. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- Knittle, Rhea Mansfield (1927). Early American Glass. New York, New York: The Century Co. OCLC 1811743. Archived from the original on 2023-07-19. Retrieved 2023-10-25.

- Kutilek, Luke (2019). "Flat Glass Manufacturing Before Float". In Sundaram, S. K. (ed.). 79th Conference on Glass Problems: A Collection of Papers Presented at the 79th Conference on Glass Problems, Greater Columbus Convention Center, Columbus, Ohio, November 4–8, 2018. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (issued by American Ceramic Society). pp. 37–54. ISBN 978-1-11963-155-2. OCLC 1099687444.

- Lanmon, Dwight P.; Palmer, Arlene M. (1976). "The Background of Glassmaking in America". Journal of Glass Studies. 18 (Special Bicentennial Issue): 14–19. JSTOR 24190008. Archived from the original on October 27, 2023. Retrieved October 27, 2023.

- Madarasz, Anne; Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania; Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center (1998). Glass: Shattering Notions. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania. ISBN 978-0-93634-001-2. OCLC 39921461.

- McKearin, Georghe S.; McKearin, Helen (1966). American Glass. New York City: Crown Publishers. OCLC 1049801744.

- Nash, Gary B. (April 1965). "The Free Society of Traders and the Early Politics of Pennsylvania". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Pennsylvania. 89 (2): 147–173. JSTOR 20089791. Archived from the original on December 7, 2023. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- Palmer, Arlene (1979). "A Philadelphia Glasshouse, 1794–1797". Journal of Glass Studies. Corning, New York: Corning Museum of Glass. 21: 102–114. JSTOR 24190039. Archived from the original on December 4, 2023. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- Poor, Henry V. (1868). Poor's Manual of Railroads for 1868–69. New York City: H.V. & H.W. Poor. OCLC 5585553. Archived from the original on May 21, 2023. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- Purvis, Thomas L. (1999). Colonial America to 1763. New York City: Facts on File. ISBN 978-1-43810-799-8. OCLC 234080971.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2007). Michael Owens and the Glass Industry. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-1-45560-883-6. OCLC 1356375205.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2011). Edward Drummond Libbey, American Glassmaker. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-78648-548-2. OCLC 753968484.

- Shotwell, David J. (2002). Glass A to Z. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. pp. 638. ISBN 978-0-87349-385-7. OCLC 440702171.

- Tillotson, E. Ward (December 1920). "Modern Glass-Making – Putting the Glass Industry on a Scientific Basis". Scientific American Monthly. New York City: Scientific American Publishing Company. II (4): 351–354. Archived from the original on November 17, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce (1917). The Glass Industry. Report on the Cost of Production of Glass in the United States. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 5705310.

- Weeks, Joseph D.; United States Census Office (1884). Report on the Manufacture of Glass. Washington, District of Columbia: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 2123984. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- Zerwick, Chloe (1990). A Short History of Glass. New York: H.N. Abrams in association with the Corning Museum of Glass. ISBN 978-0-81093-801-4. OCLC 20220721.

External links

- Historical American Glass

- Jamestown and New Jersey - University of Central Florida History Department

- Jamestown Glasshouse - National Park Service