The economic history of Latin America covers the development of the Latin American economy from 2500 BCE to the start of the 21st century.

In the pre-contact era, Latin America did not have an integrated economy. The indigenous peoples, particularly the Aztec Empire in central Mexico and the Inca Empire in the Andean region, had complex socioeconomic structures. However, their economic and political systems were more isolated due to the difficulty of north-south movement. From the beginning of the 16th century until the early 19th century, the New World was largely under the dominion of the Spanish Empire and the Portuguese Empire. The prosperity rested on the production and exportation of two primary commodities: silver and sugar. After independence, Britain exerted influence through economic neo-colonialism and private investment.

World War I (1914–1918) had a disruptive effect on British and European investments. Germany lost its trade connections and Britain suffered significant losses as the United States emerged as the dominant economic power in the region. The negative impact of the Great Depression of the 1930s was reversed by Allied purchases in World War II. Latin America countries accumulated financial reserves that were used to foster industrial expansion through import substitution industrialization. In the 1970s the region took on debt to fuel economic growth and integrate into the global market. The prospect of export earnings led to large loans denominated in U.S. dollars to expand economic capacity. Foreign capital flowed into the region, creating financial links between developed and developing nations, while the dangers of this arrangement were overlooked. In the 1980s and 1990s, most governments implemented structural reforms. These reforms included trade liberalization and privatization, often imposed as conditions for loans by the IMF and the World Bank. The worst hit countries sent migrants to the U.S., and their remittances home became increasingly important.

Pre–European contact

_p360.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)

There was no integrated economy in Latin America prior to European contact, when the region was then incorporated into the Spanish empire and the Portuguese empire. The people of the western hemisphere (so-called "Indians") had various levels of socioeconomic complexities. The most complex and extensive at the time of European contact were the Aztec empire in central Mexico and the Inca empire in the Andean region, which arose without contact with the Eastern Hemisphere prior to the late fifteenth-century European voyages. The north–south axis of Latin America, with the little east–west continental area, meant that movement of people, animals, and plants was more challenging than in Eurasia, where similar climates occur along the same latitudes. This prompted the rise of more isolated economic and political systems in pre-contact Latin America.[1] Much of what is known about pre-contact Latin American economies is found in European accounts at contact and in archeological records.[2] The sizes of indigenous populations, their organizational complexities and their geographical locations, especially the existence of exploitable resources in their vicinities had a major impact on where Iberians at contact, chose to settle or avoid in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. "The Indian peoples and the resources of their lands were the primary determinants of regional differentiation."[3]

Civilizations in Mexico and the Andes

In Mesoamerica and the highland Andean regions, complex indigenous civilizations developed as agricultural surpluses allowed social and political hierarchies to develop. In central Mexico and the central Andes where large sedentary, hierarchically organized populations lived, large tributary regimes (or empires) emerged, and there were cycles of ethno-political control of territory, which ceased at the boundaries of sedentary populations. Smaller units functioned within these larger empires during the pre-contact period, and became the foundation for European control in the early contact period. In both central Mexico and the central Andes, households of commoners cultivated lands and rendered tributes and labor to local authorities, who would then forward goods to authorities further up the hierarchy. In the Circum-Caribbean region, Amazonia, the peripheries of North and South America, semi-sedentary and non-sedentary nomadic peoples had much political or economic integration.[4] The Aztec empire in central Mexico and the Inca empire in the highland Andes had both ruled for approximately a century before the arrival of the Spaniards in the early sixteenth century.

The Mesoamerican and Andean civilizations developed in the absence of animal power and complicated agricultural tools. In Mesoamerica, there was extensive cultivation of maize, accomplished by hand-held digging sticks, and harvesting of ripened cobs done manually. In the Andes, with steep hillsides and relatively little flat land for agriculture, the people built terraces to increase agricultural land. In general, there was no such general modification of the topography in Mesoamerica, but at the southern freshwater portion of the central lake system, the natives built chinampas and mounds of earth for intense cultivation. In Mesoamerica there were no large domesticated animals prior to the arrival of the Spaniards to ease labor or provide meat, manure, or hides. In the Andes, the staple crops were potatoes, quinoa and maize, cultivated using human labor. New World camelids such as llamas and alpacas were domesticated by the people and were used as pack animals for light loads and source for wool, meat and guano.[5] There were no wheeled vehicles in either region. Both Mesoamerica and central Andes cultivated cotton, which was woven into lengths of textiles and worn by locals and rendered in tribute.

Tribute and trade

The Mesoamerica and the Inca empires are required to make payments of tributes in labor and material goods. However, in contrast to Mesoamerica's trade and markets, the economy of Inca empire functioned without markets or a medium of exchange (money). The Inca economy has been described in contradictory ways by scholars: as "feudal, slave, socialist (here one may choose between socialist paradise or socialist tyranny)".[6] The Inca rulers constructed large warehouses or Qullqa to store foodstuffs for the Inca military, to supply goods to the populace during ritual feasting, and to aid the population in lean years of bad harvests.

The Incas had an extensive road system, linking key areas of the empire to some parts that are extant in modern era. The roads were used by the military for transporting goods using llamas and for warehousing of suppliesin stone-built qullqas. Tambos or stopping places were built approximately a day's travel along the roads, near the warehouses. Gorges were spanned by rope bridges, which did not permit pack animal use. The Inca road system was a costly investment in permanent infrastructure, which had no equivalence in the Aztec empire. There were land transport routes without improvement, with the exception of the causeways linking the island where the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan was located. Sections of the road network could be removed to prevent invading forces. Around the lake system of central Mexico, canoes transported people and goods.

In Mesoamerica, trade networks and fixed markets were established quite early during the formative period (c. 2500 BCE – 250 CE). Trade differs from tribute in that, tribute was one-way, from the subordinate to the ruling power, whereas trade was a two-way exchange with profit for a desired outcome.[7] Many settlements developed craft or crop specializations. Some market places functioned as regularly scheduled one-day markets, while others such as the great market at Tlatelolco, was a vast fixed emporium of goods flowing to the capital of the Aztec empire, Tenochtitlan. That market was described in detail by Spanish conqueror Bernal Díaz del Castillo in his first-person account of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire.[8]

The Nahuatl word for market place tianquiztli, has become in modified version in modern Mexican Spanish, the word tianguis. Many Mexican towns with significant indigenous population continue to hold regularly scheduled market days, frequented by locals for ordinary household or work goods, with craft goods being particularly appealing to tourists. During the Aztec period, an elite group of long-distance merchants, the pochteca functioned as traders in high value goods as well as scouts to identify potential areas for future conquests for the Aztec Triple Alliance. They were organized into a guild-like structure, such that, the non-noble elites became emissaries of the Aztec state, thereby benefiting the investors in their expeditions and gaining state protection for their activities.[9] High value goods included cacao, quetzal feathers, and exotic animal skins, such as jaguars. Since goods had to be transported by human porters called tlameme in Nahuatl, bulk products such as maize were not part of the long-distance trade. Cacao beans functioned as a medium of exchange in the Aztec period.

Record keeping

Only in Mesoamerica did a system of writing develop and used for record keeping of tributes rendered from specific regions; such as seen in Codex Mendoza with polities in that region shown using a unique pictogram. The collective tributes rendered from that particular region was also shown in a pictographic fashion. In the Andean region, no system of writing developed, but record keeping was accomplished using the quipu, knots that could record information.

Circum-Caribbean, Amazonia, and peripheral areas

The islands of the Caribbean were fairly densely populated with sedentary, subsistence agriculturalists. No complex hierarchical social or political system evolved there. There were no tribute or labor requirements of inhabitants that could be co-opted by the Europeans upon their arrival as subsequently recorded in central Mexico and the Andean regions.

There were however, evidences of pre-contact trade in the Circum-Caribbean region, with an early European report by Peter Martyr noting canoes filled with trade goods, including cotton cloth, copper bells, copper axes (likely from Michoacan), stone knives, cleavers, ceramics and cacao beans, used for money. Small gold ornaments and jewelry were created in the region, but there were no evidences of metals being used as a medium of exchange nor being highly valued except as ornamentations. The natives did not know how to mine gold, but knew where nuggets could be found in streams. On the Pearl Coast of Venezuela, natives had collected large numbers of pearls, and, with the arrival of the Europeans, were ready to use them in trade.[10]

In northern Mexico, the southern part of South America, and in Amazonia, there were populations of semi-sedentary and nomadic peoples living in small groups pursuing subsistence activities. In the tropical rain forests of South America, the Arawakan, Cariban, and Tupian peoples lived, often pursuing slash-and-burn agriculture and moving when soil fertility declined after a couple of planting seasons. Hunting and fishing often supplemented the crops. The Caribs, for whom the Caribbean is named, were a mobile maritime people, with ocean going canoes used in long-distance voyages, warfare, and fishing. They were fierce and aggressive warriors, and with the arrival of the Europeans, hostile, mobile, resistant to conquest, and accused of cannibalism.[11] Indigenous peoples in northern Mexico, called Chichimecas by the Aztecs, were hunter-gatherers. The settled populations of central Mexico viewed these groups with contempt as barbarians, and the contempt was reciprocated.[12] In both North America and southern South America, these indigenous groups resisted European conquest, especially effectively, when they acquired the horse.

Colonial era and Independence (ca. 1500–1850)

The Spanish empire and the Portuguese empire ruled much of the New World from the early sixteenth century until the early nineteenth, when Spanish America and Brazil gained their independence. The wealth and importance of colonial Latin America was based on two main export products: silver and sugar. Many histories of the colonial era end with the political events of independence, but a number of economic historians see important continuities between the colonial era and the post-independence era up to around 1850. The continuities from the colonial era in the economies and institutions had an important impact on the new nation-states' subsequent development.[13][14]

Spanish conquest and the Caribbean economy

Spain quickly established two full colonies on Caribbean islands, especially Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and Cuba, following the first voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1492. They founded cities as permanent settlements, where institutions of crown rule were established for civil administration and the Roman Catholic Church. Cities attracted a range of settlers. In 1499 Spanish expeditions began to exploit Margarita and Cubagua abundant pearl oysters, enslaving the indigenous people of the islands and harvesting the pearls intensively. They became one of the most valuable resources of the incipient Spanish Empire in the Americas between 1508 and 1531, by which time the local indigenous population and the pearl oysters had been devastated.[15] Although the Spanish were to encounter the high civilizations of the Aztecs and the Incas in the early sixteenth century, their quarter-century of settlement in the Caribbean established some important patterns that persisted. Spanish expansionism had a tradition dating to the reconquest of the peninsula from the Muslims, completed in 1492. Participants in the military campaigns expected material rewards for their service. In the New World, these rewards to Spaniards were grants to individual men for the labor service and tribute of particular indigenous communities, known as the encomienda. Evidence of gold in the Caribbean islands prompted Spanish holders of encomiendas to compel their indigenous to mine for gold in streams, often to the detriment of cultivating their crops. Placer mining initially produced enough wealth to keep the Spanish enterprise going, but the indigenous population was in precipitous decline even before the easily exploitable deposits were exhausted by around 1515. Spanish exploration sought indigenous slaves to replace the native populations of the first Spanish settlements. Spaniards sought another high value product and began cultivating sugar cane, a crop imported from Spanish-controlled Atlantic islands. Indigenous labor was replaced by African slave labor, and initiated centuries of the slave trade.[16] Even with a viable export product, the Spanish settlements in the Caribbean were economically disappointing. Nonetheless, in 1503 the crown established the Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) in Seville to control trade and immigration to the New World. It remained an integral part of Spanish political and economic policy during the colonial era.[17] It was not until the accidental Spanish encounter with mainland Mexico and subsequent Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire (1519–21) that Spain's dreams of wealth from the New World materialized.

Once Spaniards encountered the mainland of North and South America, it was clear to them that there were significant factor endowments, in particular large deposits of silver and large, stratified populations of indigenous whose labor Spaniards could exploit. As in the Caribbean, individual Spanish conquerors in Mexico and Peru gained access to indigenous labor through the encomienda, but the indigenous populations were larger and their labor and tribute were mobilized by their indigenous rulers through existing mechanisms. As the importance of the conquest of central Mexico became known in Spain, Spaniards immigrated to the New World in great numbers. At the same time, the crown became concerned that the small group of Spanish conquerors holding encomiendas monopolized much of the indigenous labor force and that the conquerors gained too much power and autonomy of the crown. The religious push for justice for the humanitarian rights of indigenous spearheaded by Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas became a justification for the crown to limit the property rights of encomenderos and expand crown control through the 1542 New Laws limiting the number of times an encomienda could be inherited. Europeans brought in viruses and bacteria such as smallpox, measles, and some unidentified diseases. The indigenous populations had no resistance, resulting in devastating epidemics causing widespread death. In economic terms, those deaths meant a smaller labor force and fewer payers of tribute goods.

In central areas, the encomienda was phased out largely by the end of the sixteenth century, with other forms of labor mobilization coming into play. Although the encomienda did not directly lead to the development of landed estates in Spanish America, encomenderos were in a position to create enterprises near where they had access to forced labor. These enterprises did lead indirectly to the development of landed estates or haciendas. The crown had attempted to expand other Spaniards' access to indigenous labor beyond the encomenderos through a system of crown-directed distribution of labor known as the examined the shift from encomienda labor awarded to just a few Spaniards via the repartimiento to later-arriving Spaniards, who had been excluded from the original awards. This had the effect of undermining the growing power of the encomendero group, but that group found ways to engage free labor to maintain the viability and profitability of their landed estates.[18]

Silver, extraction, and labor systems

The Spanish discovery of silver in huge deposits was the great transformative commodity for the Spanish empire's economy. Discovered Upper Peru (now Bolivia) at Potosí and in northern Mexico, silver mining became the economic motor of the Spanish empire.[19] Spain's economic power was built on silver exports from Spanish America. The silver peso was both an export commodity as well as the first global money, transforming the economies of Europe as well as China.[20] In Peru silver mining benefited from its single location in the zone of dense Andean settlement, so that Spanish miner owners could utilize the forced labor of the prehiapanic system of the mita.[21][22][23] Also highly important for the Peruvian case is that there was a source of mercury silver and gold amalgamation, used in processing, at the relatively close by Huancavelica mine. Since mercury is a poison, there were ecological and health impacts on human and animal populations.[24][25]

Colonial silver extraction techniques developed over time. The early colonial mining technique of sistema del rato (a system which led to underground twisting tunnels) led to many mining problems, but was developed out of the lack of experienced miners and the Spanish Crown's desire to extract as many royalties as possible. The next advancement in extraction techniques was the cutting of adits (socavones) which, according to historian Peter Bakewell, “provided ventilation, drainage and easy extraction of ore and waste." The 16th Century bombas (pumps) helped drain mines, animal-powered "whims" were then commonly used for extracting water and ore, and "blasting" was commonly used in the 18th century.[26]

After silver ore was extracted, it had to be processed. Silver ore was taken to the amalgamation refinery to be processed with a stamp mill which ran on water, horses, or mules depending on what was available in the local environment. Certain areas of New Spain did not have water to run the stamp mills, and other areas were not able to sustain animals as a power source for the mills. Water-driven mills ended up proving more efficient and effective than animal-powered mills, making water a necessary resource for most mining productions.[26]

Silver was further refined by the complex amalgamation process, which was continually developed in America based on rudimentary German techniques. The amalgamation technique of patio (developed in the early 17th century) was claimed to be one of the most efficient ways to refine silver ore, according to German experts in silver mining. The technique mixed ground ore with catalysts (salt or copper pyrite) to create a paste which would be dried and leave silver amalgam remaining.[27] It required little water and could be set up anywhere, which would have been hugely beneficial to silver miners of New Spain. Historian Peter Bakewell claims, “No other single innovation in refining was as effective as magistral (copper sulphate derived from pyrites).” This material became widely used throughout Spanish America to refine silver during the amalgamation process. German miners provided “smelting technology,” another refinement technique. These furnaces were cheap, and “it was the preferred technique of the poor individual miner or of the Indian labourer who received ore as part of his wage.”[26] However, certain historians argue that the process of smelting was extremely destructive to the natural land surrounding the mines. It originally promoted deforestation in order to fuel the smelting process, and the introduction of mercury to the process led to poisoned soil and water sources, and many Indian labourers suffered from mercury poisoning as a result.[28]

Many developments in silver mining technology and techniques allowed for the expansion of silver to take place in lands with little water or animals to provide power. These developments also allowed for silver mining to expand because of its cost effectiveness. However, historians have found that silver mining production during the colonial period had massive and devastating impacts on the environment and the Indians who inhabited the lands which were taken over by the mining industry.

Most mining sites in Mexico's north, outside the zone of sedentary Indian populations, did not have access to forced indigenous labor, with the notable exception of Taxco,[29] so that mining necessitated the creation of a labor force from elsewhere. Zacatecas,[30] Guanajuato,[31] and Parral[32] were found in the region of so-called barbarian Indians, or Chichimecas, who resisted conquest. The Chichimec War lasted over 50 years, with the Spaniards finally bringing the conflict through supplying the indigenous with food, blankets, and other goods in what was terms "peace by purchase," securing the transportation routes and Spanish settlements from further attack.[33] Had the northern silver mines not been so lucrative, Spaniards would likely not have attempted to settle and control the territory. California did not look promising enough in the Spanish period to attract significant Spanish settlement, but in 1849 after it was acquired by the U.S. in the Mexican–American War, huge deposits of gold were discovered.

Sugar, slavery, and plantations

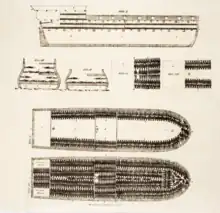

Sugar was the other major export product in the colonial era, using the factor endowments of rich soils, tropical climate, and areas of cultivation close to coasts to transport by the refined sugar to Europe. Labor, a key factor for production was missing, since the indigenous populations in the tropical areas were initially small and did not have a pre-existing system of tribute and labor requirements. That small population then disappeared entirely. Brazil, Venezuela and islands in the Caribbean, cultivated sugar on a huge scale, using a labor force of African slaves traded to the tropics as an export commodity from Africa, dating from the earliest period of Iberian colonization until the mid nineteenth century.[34] Regions of sugar cultivation had a very small number of wealthy white owners, while the vast majority of the population was black slaves. The structure of cultivation and processing of sugar had a major impact on how the economies developed. Sugar must be processed immediately upon the cane being cut, so that cultivation and highly technical processing were done as a single enterprise. Both demanded high inputs of capital and credit, and a specialized skilled workforce as well as large number of slaves to do cultivation and harvest.[35]

The slave trade was initially in the hands of the Portuguese, who controlled the coasts of West and East Africa and into the Indian Ocean, with most of the Atlantic slave trade coming from West Africa. Staging areas were established in West Africa, and slave ships collected large cargoes of Africans, who first endured the Middle Passage across the Atlantic. If they survived, they were sold in slave markets in port cities of Brazil and Spanish America. The British attempted to suppress the slave trade, but it continued into the 1840s, with slavery persisting as a labor system until the late nineteenth century in Brazil and Cuba.

The development of the colonial economy

In Spanish America, the initial economy was one based on the tribute and labor of settled indigenous populations that were redirected to the small Spanish sector. But as the Spanish population grew and settled in newly founded Spanish cities, enterprises were created to supply those urban populations with foodstuffs and other necessities. This meant the development of agricultural enterprises and cattle and sheep ranches near cities, so that the development of the rural economy was closely tied to the urban centers.

A major factor in the development of the colonial economy and its integration into the emerging global economy was the difficulty in transportation. There were no navigable rivers to provide cheap transportation and few roads, meaning that pack animals were used extensively, particularly sure-footed mules loaded with goods. Getting goods to markets or ports generally involved mule trains.

There were other agricultural export commodities during this early period were cochineal, a color-fast red dye made from the bodies of insects growing on nopal cactuses in Mexico; cacao, a tropical product cultivated in the prehispanic era in central Mexico and Central America, in a region now called Mesoamerica; indigo, cultivated in Central America; vanilla, cultivated in tropical regions of Mexico and Central America. Production was in the hands of a wealthy few, while the labor force was poor and indigenous. In regions with no major indigenous populations or exploitable mineral resources, a pastoral ranching economy developed.

The environmental impact of economic activity, including the Columbian Exchange have become subjects for research in recent years.[36][37][38][39] The importation of sheep damaged the environment, since their grazing grass down to the roots prevented its regeneration.[40] Cattle, sheep, horses, and donkeys imported from Europe and proliferated on haciendas and ranches in regions of sparse human settlement, and contributed to the development of regional economies. Cattle and sheep were used for food as well as leather, tallow, wool, and other products. Mules were vital to transporting goods and people, especially since roads were unpaved and virtually impassable during the rainy season. A few large estate owners derived wealth from economies of scale and made their profits from supplying the local and regional economies, but the majority of the rural population was poor.

Manufactured goods

Most manufactured goods for elite consumers were mainly of European origin, including textiles and books, with porcelains and silk coming from China via the Spanish Philippine trade, known as the Manila Galleon. Profits from the colonial export economies allowed elites to purchase these foreign luxury goods. There was virtually no local manufacturing of consumer goods, with the exception of rough woolen cloth made from locally raised sheep destined for an urban mass market. The cloth was produced in small-scale textile workshops, best documented in Peru and Mexico, called obrajes, which also functioned as jails. Cheap alcohol for the poor was also produced, including pulque, chicha, and rum, but Spanish American elites drank wine imported from Spain. Tobacco was cultivated in various regions of Latin America for local consumption, but in the eighteenth century, the Spanish crown created a monopoly on the cultivation of tobacco and created royal factories to produce cigars and cigarettes.[41]

Coca, the Andean plant now processed into cocaine, was cultivated and the leaves were consumed by indigenous particularly in mining areas. Production and distribution of coca became big business, with non-indigenous owners of production sites, speculators, and merchants, but consumers consisted of indigenous male miners and local indigenous women sellers. The Catholic church benefited from coca production, since it was by far the most valuable agricultural product and contributor to the tithe, a ten percent tax on agriculture benefiting the church.[42]

Transatlantic and transpacific trade in a closed system

Transatlantic trade was regulated by royal Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) based in Seville. Inter-regional trade was severely limited with merchants based in Spain and with overseas connections in the main colonial centers controlling the transatlantic trade.[43][44][45][46] British traders began making inroads into the theoretically closed Spanish system in the eighteenth century,[47] and the Spanish crown instituted a series of changes in policy in the eighteenth century, known as the Bourbon Reforms, designed to bring the Spanish America under closer crown control. However, one innovation was comercio libre ("free commerce"), which was not free trade as generally understood, but allowed all Spanish and Spanish American ports to be accessible to each other, excluding foreign traders, in a move to stimulate economic activity yet maintain crown control. At independence in the early nineteenth century, Spanish America and Brazil had no foreign investment or direct, legal contact with economic partners beyond those allowed within controlled trade.

Though the legislation passed by the Bourbons did much to reform the Empire, it was not enough to save it. The racial tensions continued to grow and massive discontent lead to a number of revolts, the most important of which were the Rebellion of Túpac Amaru II and Revolt of the Comuneros. Criollos, Mestizos, and Indians were among the most common to be involved in such revolts.[57] In the early nineteenth century, Spanish America and Brazil had no foreign investment or direct, legal contact with economic partners beyond those allowed within controlled trade. Over time, these facts led to the wars for the independence of the American colonies.

Economic impact of independence

Independence in Spanish America (except Cuba and Puerto Rico) and Brazil in the early nineteenth century had economic consequences as well as the obvious political one of sovereignty. New nation-states participated in the international economy.[48] However, the gap between Latin America and Anglo-Saxon America widened. Scholars have attempted to account for the divergent paths of hemispheric development and prosperity between Latin America and British North America (the United States and Canada), seeking how Latin American economies fell behind English North America, which became an economic dynamo in the nineteenth century.[49][50][51][52]

In the period before independence, Spanish America and Brazil were more important economically than the small English colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. The English colonies of the mid-Atlantic, New England, and Canada had a temperate climate, no major indigenous populations whose labor could be exploited, and no major export commodities that would have encouraged the importation of black slaves. The southern English colonies with plantation agriculture and large black slave populations share more characteristics with Brazil and the Caribbean than the northern English colonies. That region is characterized by the family farm, with a homogeneous European-descent population with no sharp divide between rich and poor. Unlike Spanish America and Brazil which restricted immigration, the northern English colonies were a magnet for migration, encouraged by the British crown.

With independence, Iberian-born Spanish merchants who were key factors in the transatlantic trade and the availability of credit to silver miners exited from Spanish America, through self-exile, expulsion, or loss of life, draining the newly independent countries of entrepreneurs and professionals. Forced indigenous labor mita was abolished in the Andean region, with few continuing with such labor on a voluntary basis. African slavery was not abolished at independence, but in many parts of Spanish America, it had already waned as an important source of labor. In Brazil in the post-independence period, African slaves were used extensively with the development of coffee as a major export product.[53] With the revolution in Haiti, which abolished slavery, many sugar plantation owners moved to Cuba, where sugar became the main cash crop.

Early Post-Independence (1830–1870)

In Spanish America, the disappearance of colonial-era economic restrictions (except for Cuba and Puerto Rico) did not produce immediate economic expansion "because investment, regional markets, credit and transport systems were disrupted" during the independence conflicts. Some regions faced greater continuity from colonial era economic patterns, mainly ones that were not involved in silver extraction and peripheral to the colonial economy.[54] Newly independent Spanish American republics did see the need to replace Spanish colonial commercial law, but they did not put in place a new code until after the mid nineteenth century due to political instability and the lack of legal expertise. Until constitutions were put in place for the new sovereign nations, the task of crafting new laws was largely on hold. The legislatures were comprised on men who had no previous experience in governing, so that it was challenging to draft laws, including those to shape economic activity. Not having a stable political structure or legal framework that guaranteed property rights made potential entrepreneurs, including foreigners, less likely to invest. The dominance of large landed estates continued throughout the early nineteenth century and beyond.[55]

Obstacles to economic growth

Many regions faced significant economic obstacles to economic growth.[56] Many areas of Latin America was less integrated and less productive than they were in the colonial period, due to the political instability. The cost of the independence wars and the lack of a stable tax collection system left the new nation-states in tight financial situations. Even in places where the destruction of economic resources was less common, disruptions in financial arrangements and trading relationships caused a decline in some economic sectors.

A key feature that prevented economic expansion following political independence was the weak or absent central governments of the new nation-states that could maintain peace, collect taxes, develop infrastructure, expand commercial agriculture, restore the mining economies, and maintain the sovereignty of territory. The Spanish and Portuguese crowns forbade foreign immigration and foreign commercial involvement, but there were structural obstacles to economic growth. These included the power of the Roman Catholic Church and its hostility to religious toleration and liberalism as a political doctrine, and continued economic power in landholding and collection of the religious tax of the tithe; the lack of power of nation-states to impose taxation, and a legacy of state monopolies, and lack of technology.[57] Elites were divided politically and had no experience with self-rule, a legacy of the Bourbon Reforms, which excluded American-born elite men from holding office. Independence from Spain and Portugal caused the breakdown of traditional commercial networks, which had been dominated by transatlantic trading houses based in Spain. The entrance of foreign merchants and imported goods led to competition with local producers and traders. Very few exports found world markets favorable enough to stimulate local growth, and very little capital was received from other countries, since foreign investors had little confidence in the security of their funds. Many new nation-states borrowed from foreign sources to fund the governments, causing the debt from the independence wars to increase.

Role of foreign powers

Latin America's political independence proved irreversible, but weak governments in Spanish American nation-states could not replicate the generally peaceful conditions of the colonial era. Although the United States was not a world power, it claimed authority over the hemisphere in the Monroe Doctrine (1823). Britain, the first country to industrialize and the world power dominating the nineteenth century, chose not to assert imperial power to rule Latin America directly, but it did have an influence on Latin American economies through neo-colonialism. Private British investment in Latin America began as early as the independence era, but increased in importance during the nineteenth century. To a lesser extent, the British government was involved. The British government did seek most favored nation status in trade, but, according to British historian D.C.M. Platt, did not promote particular British commercial enterprises.[58][59] Britain sought to end the African slave trade to Brazil and to the Spanish colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico and to open Latin America to British merchants.[60] Latin America became an outlet for Britain's manufactures, but the results were disappointing when merchants expected payment in silver. However, when Latin American exports filled British ships for the return voyage and economic growth was stimulated, the boom in Latin American exports occurred just after the middle of the Nineteenth century.[61]

Export Booms (1870–1914)

The late 1800s represented a fundamental shift in the new developing Latin American nations. This transition was characterized by a re-orientation towards world markets, which was well underway before 1880.[62] When Europe and the United States experienced an increase of industrialization, they realized the value of the raw materials in Latin America, which caused Latin American countries to move towards export economies. This economic growth also catalyzed social and political developments that constituted a new order. Historian Colin M. Lewis argues that "In relative terms, no other region of the world registered a similar increase in its share of world trade, finance, and population: Latin America gained relative presence in the world economy at the expense of other regions."[63]

Favorable Government Policies

As the political situation stabilized toward the late nineteenth century, many governments actively promoted policies to attract capital and labor. The phrase "order and progress" were key concepts for this new stage for Latin American development, and actually put on the flag of the republic of Brazil in 1889, following the ouster of the monarchy. Mexico created legal guarantees for foreign investors during the regime of Porfirio Díaz (1876–1911), which overturned the legacy of colonial law. Colonial law vested the state with subsoil rights and gave full ownership rights to private investors. In Argentina, the constitution of 1853 gave foreigners basic civil rights. Many governments actively promoted foreign immigration, both to create a low-wage labor force, but also to change the racial and ethnic profile of populations. Laws ensuring religious toleration opened the door to Protestants.[64] With unequal treaties with colonial powers behind them, major Latin Americans countries were able to implement autonomous trade policies during this period. They imposed some of the highest import tariffs in the world, with average tariffs between 17% and 47%[65] Average per capita income during this period rose at the rapid annual rate of 1.8%.[66]

Transportation and Communication

There were revolutions in communications and transportation that had major impacts on the economy. Much of the infrastructure was built through foreign financing, with financiers shifting from extending loans to governments to investments in infrastructure, such as railways and utilities, as well as mining and oil drilling. The construction of railroads transformed many regions economically. Given the lack of navigable river systems, which had facilitated economic development of the United States, the innovation of railroad construction overcame significant topographical obstacles and high transaction costs. Where large networks were constructed, they facilitated domestic economic integration as well as linking production zones to ports and borders for regional or international trade. "Increasing exports of primary commodities, rising imports of capital goods, the expansion of activities drawing directly and indirectly on overseas investment, the rising share of modern manufacturing in output, and a generalized increase in the pace and scope of economic activity were all tied closely to the timing and character of the region's infrastructural development."[67] In some cases, railway lines did not produce such wide-ranging economic changes, with directly linked zones of production or extraction to ports without linkages to larger internal networks. An example is line built from the nitrate zone in northern Chile, seized during the War of the Pacific, to the coast. British capital facilitated railway construction in Argentina, Brazil, Peru, and Mexico, with significant economic impact.[68][69]

There was investment in improved port facilities to accommodate steamships, relieving a bottleneck in the transportation links, and resulting in ocean shipping costs dropping significantly. Brazil and Argentina showed the greatest growth in merchant steam shipping, with both foreign and domestic ships participating in the commerce. Although improved port facilities affected Latin American economies, it is not a well-studied topic.[70] An exception is the opening of new port facilities in Buenos Aires in 1897.[71] Innovations in communication, including the telegraph and submarine cables facilitated the transmission of information, vital to running far-flung business enterprises. Telegraph lines were often built beside railway lines.

Export commodities

Guano

An early boom and bust export in Peru was guano, bird excrement that contains high amounts of nitrates used for fertilizer. Deposits on islands owned by Peru were mined industrially and exported to Europe. The extraction was facilitated by Peruvian government policy.[72]

Sugar

Sugar remained an important export commodity, but it fell in importance in Brazil, which shifted to coffee cultivation. Sugar expanded in the last Spanish colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico with African slave labor, which was still legal in the Spanish empire.[73][74] Sugar had previously been considered a luxury for consumers with little cash, but with its drop in price a mass market developed.[75][76] Previously Cuba had had a mix of agricultural products, but it became essentially a mono-crop export, with tobacco continuing to be cultivated for domestic consumption and for export.[77]

Wheat

Wheat production for export was stimulated in Chile during the California gold rush of the mid-nineteenth century, but ended when transportation infrastructure in the U.S. was built. In Argentina, wheat became a major export product to Britain, since transport costs had dropped enough to make such a bulk product profitable.[78] Wheat grown on the rich virgin soil of the pampas was mechanized on large enterprises during the boom.[79]

Coffee

As foreign demand for coffee expanded in the nineteenth century, many areas of Latin America turned to its cultivation, where the climate was conducive. Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Costa Rica became major coffee producers, which disrupted traditional land tenure patterns and necessitated a secure workforce. Brazil became dependent on the single crop of coffee.[80] The expansion of coffee cultivation was a major factor in the persistence of slavery in Brazil, where it had been on the wane as Brazil's share of sugar production fell. Slave labor was redirected to coffee cultivation.

Rubber

A case study of a commodity boom and bust is the Amazon rubber boom.[81] With the increasing pace of industrialization and the invention of the automobile, rubber became an important component. Found wild in Brazil and Peru, rubber trees were tapped by workers who collected the raw sap for later processing. The abuses against indigenous were chronicled by the British consul, Sir Roger Casement.[82]

Petroleum

With the discovery of petroleum on the Gulf Coast of Mexico, British and U.S. enterprises invested heavily in drilling crude oil. Laws passed during the regime of Porfirio Díaz reversed colonial law that gave the state rights to subsoil resources, but liberal policies gave full ownership to oil companies to exploit the oil. Foreign ownership of oil was an issue in Mexico, with expropriation of foreign companies in 1938. Large petroleum deposits were found in Venezuela just after the turn of the twentieth century and has become the country's major export commodity.

Mining

Silver declined as a major export, but lesser minerals such as copper and tin became important starting in the late nineteenth century, with foreign investors providing capital. Tin became the main export product of Bolivia, eventually replacing silver, but silver extraction prompted the building of a railway line, which then allowed tin mining to be profitable.[83] In Chile, copper mining became its most important export. It was a significant industry in Mexico as well.[84] Extraction of nitrates from regions Chile acquired from Bolivia and Peru in its victory in the War of the Pacific became an important source of revenue.

Environmental degradation

Increasingly scholars have focused on the environmental costs of export economies, including deforestation, impacts of monoculture of sugar, bananas, and other agricultural exports, mining and other extractive industries on air, soil, and human populations.

Immigration and Labor

Following independence, most Latin American countries tried to attract immigrants, but only after political stability, increased foreign investment, and decreasing transportation costs on steamships, along with their speed and comfort in transit did migrants go in large numbers. Immigration from Europe as well as Asia provided a low-wage workforce for agriculture and industry.[85][86] Foreign immigrants were drawn to particular countries in Latin America: Argentina, Brazil (following the abolition of slavery), Uruguay, and Cuba, but the U.S. was the top destination in this period.[87] Seasonal migration between Italy and Argentina developed, with laborers (so-called golondrinas "swallows") able to take advantage of the seasonal differences in the harvests and the higher wages paid in Argentina. Many went as single men rather than as part of families, who settled permanently.

In Peru, Chinese laborers were brought to work as virtual slaves on coastal sugar plantations, allowing the industry to survive, but when immigration was ended in the 1870s, forced labor was ended in the 1870s, landowners sought domestic laborers who migrated from other areas of Peru and kept in coercive conditions.[88][89] In Brazil, recruitment of Japanese laborers was important for the coffee industry following the abolition of black slavery.[90] Brazil also subsidized immigration from Europe, providing a low-wage workforce for coffee cultivation.[91]

The labor force also expanded to include women working outside of the domestic sphere, including in coffee cultivation in Guatemala and in the industrial sector, examined in a case study in Antioquia, Colombia.[92]

New Order emerging (1914–1945)

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 disrupted British and other European investment in Latin America, and the international economic order vanished.[93] In the post–World War I period, Germany was eclipsed from trade ties with Latin America and Great Britain experienced significantly losses, leaving the United States in the dominant position.

Impact of World War I

During the World War I period (1914–18), few Latin Americans identified with either side of the conflict, although Germany attempted to draw Mexico into an alliance with the promise of the return of territories lost to the U.S. in the U.S.–Mexico War. The only country to enter the conflict was Brazil, which followed the example of the United States and declared war on Germany. Despite the general neutrality, all areas suffered disruption of trade and capital flows, since transatlantic transport was disrupted and European countries were focused on the war rather than investing overseas. The Latin American countries that were most affected were those that developed significant trade relations with Europe. Argentina, for example, experienced a sharp decline in trade as the Allied Powers diverted their products elsewhere, and Germany became inaccessible.

With the suspension of the gold standard for currencies, movement of capital was interrupted and European banks called in loans to Latin America, provoking domestic crises. Direct foreign investment from Great Britain, the dominant European power, ended. The United States, which was neutral in World War I until 1917, sharply increased its purchases of Latin American commodities. Commodities useful for the war, such as metals, petroleum, and nitrates, increased in value, and source countries (Mexico, Peru, Bolivia, and Chile) were favoured.

Transportation

The United States was in an advantageous position to expand trade with Latin America, with already strong ties with Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. With the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 and the disruption of the transatlantic trade, U.S. exports to Latin America increased.[94] As transportation in the Caribbean became cheaper and more available, fragile tropical imports, especially bananas could be reach mass markets in the United States. U.S. Navy ships deemed surplus following the Spanish–American War (1898) were made available to the United Fruit Company, which created its "Great White Fleet." Latin American countries dominated by U.S. interests were dubbed banana republics.

Banking systems

An important development in this period was the creation and expansion of the banking system, especially the establishment central banks in most Latin American countries, to regulate the money supply and implement monetary policy. In addition, a number of countries created more specialized state banks for development (industrial, agricultural, and foreign trade) in the 1930s and 1940s. The U.S. entered the private banking sector in Latin America in the Caribbean and in South America, opening branch banks.[95] A number of Latin American countries invited prominent Princeton University professor Edwin W. Kemmerer ("the money doctor") to advise them on financial matters.[96] He advocated financial plans based on strong currencies, the gold standard, central banks, and balanced budgets. The 1920s saw the establishment of central banks in the 1920s in the Andean region (Chile, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Colombia) as a direct result of the Kemmerer missions.[97]

In Mexico, the Banco de México was created in 1925, during the post-Mexican Revolution presidency of Plutarco Elías Calles using Mexican experts, such as Manuel Gómez Morín, rather than advisers from the U.S. As industrialization, agricultural reform, and regulated foreign commercial ties became important in Mexico, the state established a number of specialized state banks. Argentina, which has longstanding ties to Great Britain, set up its central bank, the Banco Central de la República de Argentina (1935) under the advice of Sir Otto Niemeyer of the Bank of England, with Raúl Prebisch as its first president.[97] Private banking also began to expand.

Changes in U.S. law that had previously prevented the opening of branch banks in foreign countries meant that branch banks were opened in places where U.S. trade ties were strong. A number of Latin American countries became not only linked to the U.S. financially, but the U.S. government pursued foreign-policy objectives.[98] Post-war commodity prices were unstable, there was an oversupply of commodities, and some governments attempted to manipulate commodity prices, such as Brazil's attempt to raise coffee prices, which in turn caused Colombia to increase its production. Since most Latin American countries had been dependent of the commodity export sector for their economic well-being, the fall in commodity prices and the lack of increase in the non-export sector left them in a weak position.[99]

Manufacturing for a domestic market

Manufacturing for either a domestic or export market had not been a major feature of Latin American economies, but some steps had been taken in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including in Argentina, often seen as the key example of an export-dependent economy, one based on beef, wool, and wheat exports to Britain. Argentina experienced growth of domestic industry in the period 1870–1930, which responded to domestic demand for goods generally not imported (beer, biscuits, cigarettes, glass, paper, shoes).[100] Beer manufacturing was established in the late nineteenth century, mainly by German immigrants to Argentina, Chile, and Mexico. Improvements in beer production that kept the product stable for longer and the development of transportation networks meant that beer reached a mass market.

Impact of the Great Depression

The external shock of the Great Depression had uneven impacts on Latin American economies. The values of exports generally decreased, but in some cases, such as Brazilian coffee, the volume of exports increased. Credit from Britain evaporated. Although the so-called money doctors from the U.S. and the U.K. made recommendations to Latin American governments on financial policies, they were generally not adopted. Latin American governments abandoned the gold standard, devalued their currencies, introduced foreign currency controls, and attempted to adjust payments for foreign debt servicing, or defaulted, including Mexico and Colombia. There was a sharp decline in imports, resulting also in the decline of revenues from import duties. In Brazil, the central government destroyed three years' worth of coffee production to keep coffee prices high.[101]

Latin America recovered relatively quickly from the worst of the Depression, but exports did not reach the levels of the late 1920s. Britain attempted to reimpose policies of preferential treatment from Argentina in the Roca-Runciman Treaty. The U.S. pressed better trade relations with Latin American countries with implementation of the Reciprocal Tariff Act of 1934, following on the Good Neighbor Policy of 1933. Nazi Germany's policies dramatically expanded its bilateral trade with various Latin American countries. There was a huge increase in Brazilian cotton exports to Germany. The 1937 recession in the U.S. affected GDP growth in Latin American countries.[102]

World War II

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Latin American trade with Germany ceased due to the insecurity of the sea lanes from German submarine activity and the British economic blockade. For Latin American countries not trading significantly with the U.S. the impacts were greater. For Latin America, the war had economic benefits as they became suppliers of products useful to the Allied war effort and they accumulated balances in hard currency as imports dwindled and the prices for war-related commodities increased. These improved Latin American governments' ability to implement programs of import substitution industrialization, which expanded substantially in the post-war period.[103]

Changing role of the state, 1945–73

Social changes

Increasing birth rates, falling death rates, migration of rural dwellers to urban centers, and the growth of the industrial sector began to change the profile of many Latin American countries. Population pressure in rural areas and the general lack of land reform (Mexico and Bolivia excepted) produced tension in rural areas, sometimes leading to violence in Colombia and Peru in the 1950s.[104] Countries expanded public education, which were increasingly aimed at incorporating marginalized groups, but the system also increased social segmentation with different tiers of quality. Schools shifted their focus over time from creating citizens of a democracy to training workers for the expanding industrial sector.[105] Actually, educational inequality, which peaked during the 19th century, began decreasing in the 20th century. Yet, the reverberations of Latin America having the highest educational inequality worldwide during the first period are still perceptible today.[106] Economic inequality and social tensions would come into sharper focus following the January 1959 Cuban Revolution.

Economic nationalism

Many Latin American governments began to actively take a role in economic development in the post-World War II era, creating state-owned companies for infrastructure projects or other enterprises, which created a new type of Latin American entrepreneur.[107]

Mexico nationalized its petroleum industry in 1938 from the British and U.S. companies that had developed it. The Mexican government did that with full legal authority, since the revolutionary-era Mexican Constitution gave the state authority to take control over natural resources, reversing the liberal legislation of the late nineteenth century granting inalienable property rights to private citizens and companies. The government of Lázaro Cárdenas expropriated foreign oil interests and created the state-owned company, Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX).[108] Mexico provided a model for other Latin American countries to nationalize their own industries in the post-war period. Brazil established the state monopoly oil company Petrobras in 1953.[109][110] Other governments also followed policies of economic nationalism and an expanded economic role for the state. In Argentina, the five-year plan promulgated by the government of Juan Perón sought to nationalize state services. In Bolivia, the 1952 revolution under Victor Paz Estenssoro overturned the small group of businessmen controlling tin, the country's main export, and nationalized the industry, and decreed a sweeping land reform and universal suffrage to adult Bolivians.[111]

Many Latin American countries benefited from their participation in World War II and accumulated financial reserves that could be mobilized for the expansion of industry through import substitution industrialization.

New Institutional frameworks for economic development

In the post-World War II era, a new framework to structure the international system emerged with the U.S. rather than Britain as the key power. In 1944, a multi-nation group, led by the United States and Britain, forged formal institutions to structure the post-war international economy: The Bretton Woods agreements created the International Monetary Fund, to stabilize the financial system and exchange rates, and the World Bank, to supply capital for infrastructure projects. The U.S. was focused on the rebuilding of Western European economies, and Latin America did not initially benefit from these new institutions. However, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), signed in 1947, did have Argentina, Chile and Cuba as signatories.[112] GATT had a legal structure to promote international trade by reducing tariffs. The Uruguay Round of GATT talks (1986–1994) resulted in the formation of the World Trade Organization.[113]

With the creation of the United Nations after World War II, that institution created the Economic Commission for Latin America, also known by its Spanish acronym CEPAL, to develop and promote economic strategies for the region. It includes members from Latin America as well as industrialized countries elsewhere. Under its second director, Argentine economist Raúl Prebisch (1950–1963), author of The Economic Development of Latin America and its Principal Problems (1950), CEPAL recommended import substitution industrialization, as a key strategy to overcome underdevelopment.[114][115] Many Latin American countries did pursue strategies of inward development and attempted regional integration, following the analyses of CEPAL, but by the end of the 1960s, economic dynamism had not been restored and "Latin American policy-making elites began to pay more attention to alternative ideas on trade and development."[116]

The lack of focus on Latin American development in the post-war period was addressed by the creation of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) was established in April 1959, by the U.S. and initially nineteen Latin American countries, to provide credit to Latin American governments for social and economic development projects. Earlier ideas for creating such a bank date to the 1890s, but did not come to fruition. However, in the post-World War II era, there was a renewed push, particularly since the newly established World Bank was more focused on rebuilding Europe. A report by Argentine economist Raúl Prebisch urged the creation of a fund to enable development of agriculture and industry. In Brazil, President Juscelino Kubitschek endorsed the plan to create such a bank, and the Eisenhower administration in the U.S. showed a strong interest in the plan and a negotiating commission was created to develop the framework for the bank. Since its founding the IDB has been headquartered in Washington, D.C., but unlike the World Bank whose directors have always been U.S. nationals, the IDB has had directors originally from Latin America. Most funded projects are economic and social infrastructure, including "agriculture, energy, industry, transportation, public health, the environment, education, science and technology, and urban development."[117] The Inter-American Development Bank was established in 1959, coincidentally the year of the Cuban Revolution; however, the role of the bank expanded as many countries saw the need for development aid to Latin America. The number of partner nations has increased over the years, with an expansion of non-borrowing nations to Western Europe, Canada, and China, providing credit to the bank.

Latin America developed a tourism industry aimed at attracting foreign and domestic travelers. In Mexico, the government developed infrastructure in Acapulco in the 1950s and Cancun, beginning in 1970, to create beach resorts. Indigenous areas that had been economic backwaters in the industrial economy became destinations for tourism, often resulting in commodification of culture.[118]

Impact of the Cuban Revolution

A major shock to the new order of U.S. hegemony in the hemisphere was the 1959 Cuban Revolution. It shifted quickly from reform within existing norms to the declaration that Cuba was a socialist nation. With Cuba's alliance with the Soviet Union, Cuba found an outlet for its sugar following the U.S. embargo on its longstanding purchases of Cuba's monoculture crop. Cuba expropriated holdings by foreigners, including large numbers of sugar plantations owned by U.S. and Canadian investors. For the United States, the threat that revolution could spread elsewhere in Latin America prompted U.S. President John F. Kennedy to proclaim the Alliance for Progress in 1961, designed to aid other Latin American governments with implementing programs to alleviate poverty and promote development.[119]

1960s–1970s

A critique of the developmentalist strategy emerged in the 1960s as dependency theory, articulated by scholars who saw Latin American countries' economic underdevelopment as resulting from the penetration of capitalism that trapped countries in a dependent position supplying commodities to the developed countries. Andre Gunder Frank's Latin America: Underdevelopment or Revolution (1969) made a significant impact as did Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Enzo Faletto's Dependency and Development in Latin America (1979). It has been superseded by other approaches including post-imperialism.[120][121][122]

A "peaceful road to socialism" appeared for a time to be possible. In 1970, Chile elected as president socialist Salvador Allende, in a plurality. This was seen as a "peaceful road to socialism," rather than armed revolution of the Cuban model. Allende attempted to implement a number of significant reforms, some of which had already been approved but not implemented by the previous administration of Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei. Frei had defeated Allende in the previous presidential election (1964) in good part because he promised significant reform without serious structural change to Chile, while maintaining rule of law. He promised agrarian reform, tax reform, and the nationalization of the copper industry. There was rising polarization and violence in Chile and increasing hostility by the administration of U.S. President Richard Nixon. A U.S.-supported military coup against Allende on September 11, 1973, ended the transition to socialism and ushered in an era of political repression and economic course changes.[123][124] The successful 1973 coup in Chile signaled that substantial political and change would not come without violence. Leftist revolutions in Nicaragua (1979) and the protracted warfare in El Salvador saw the U.S. back low-intensity warfare in the 1980s, one component of which was damaging their economies.

In an effort to diversify their economies by avoiding over reliance on the export of raw materials, Latin American nations argued that their developing industries needed higher tariffs to protect against the importation of manufactured goods from more established competitors in more industrialized areas of the world. These views largely prevailed in the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and were even accepted in 1964 as the new part IV of the GATT (General Agreement of Tariffs and Trade).[125] Per capita income in Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s grew at the rapid annual rate of 3.1%.[126]

Reorientations 1970s–2000s

By the 1970s, the world economy had undergone significant changes and Latin American countries were seeing the limits of inward turning development, which had been based on pessimism about the potential of export-led growth. In the developed world, rising wages made seeking lower-wage locations to build factories more attractive. Multinational corporations (MNCs) had movable capital to invest in developing countries, particularly in Asia. Latin American countries took note as these newly industrializing countries experienced significant growth in GDP.[127] As Latin American countries became more open to foreign investment and export-led growth in manufacturing, the stable post-war financial system of the Bretton Woods agreements, which had depended on fixed exchange rates tied to the value of the U.S. dollar was ending. In 1971, the U.S. ended the U.S. dollar's convertibility to gold, which made it difficult for Latin American countries, as well as other developing countries to make economic decisions.[116] At the same time, there was a boom in commodity prices, particularly oil as the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries OPEC limited production while demand continued to soar, resulting in worldwide price rises in the price per barrel. With the rise in oil prices, oil producing countries had considerable capital to invest and international banks based in the U.S. expanded their reach, investing in Latin America.[128]

Latin American countries took on debt to fuel the economic growth and integration into a globalizing market. The promise of export earnings using borrowed money enticed many Latin American countries to take on loans, valued in U.S. dollars, that could expand their economic capacity. Creditors were eager to invest in Latin America, since in the mid-1970s real interest rates were low and optimistic commodity forecasts made lending a rational economic decision. Foreign capital poured into Latin America, linking developed and developing countries financially. The vulnerabilities in the arrangement were initially ignored.[129]

Mexico in the early 1970s saw economic stagnation. With the discovery of huge oil reserves in the Gulf of Mexico in the mid-1970s, Mexico appeared to be able to take advantage of high oil prices to spend on industrialization as well as fund social programs. Foreign banks were eager to lend to Mexico, since it seemed to be stable, had effectively a one-party political system that had kept social unrest to a minimum. Also reassuring to international lenders was that Mexico had maintained a fixed exchange rate with the U.S. dollar since 1954. President José López Portillo (1976–82) broke with long-standing treasury practice of not taking on foreign debt, and borrowed extensively in U.S. dollars against future oil revenues. With the subsequent crash of the price of oil in 1981–82, Mexico's economy was in shambles and unable to make payments on the loans. The government devalued its currency, placed a 90-day moratorium on payment of the principal on external public debt, and finally López Portillo nationalized banking in the country and exchange controls on currency were imposed without warning. International lending institutions were themselves vulnerable when Mexico defaulted on its debt, since Mexican debt accounted for 44% of the capital of the nine largest U.S. banks.[130][131]

Some Latin American countries did not take part in this trend toward heavy borrowing from international banks. Cuba remained dependent on the Soviet Union to prop up its economy, until the collapse of that state in the 1990s cut Cuba off, sending it into a severe economic crisis known as the Special Period. Colombia limited its borrowing and instead instituted tax reform, which raised government revenues significantly.[132] But the general economic downturn of the 1980s plunged Latin American economies into crisis.[133]

Latin American countries' borrowing from U.S. and other international banks exposed them to extreme risk when interest rates rose in the lending countries and commodity prices fell in the borrowing countries. Capital flows to Latin America reversed, with capital flight from Latin America immediately preceding the 1982 shock. The rise in interest rates affected borrowing countries, since servicing the debt directly affected national budgets. In many cases, the national currency was devalued, which cut demand for imports that now cost more. Inflation hit new levels, with the poor acutely affected. Governments cut social spending, and overall, poverty grew, and income distribution worsened.[134]

Washington Consensus

The economic crisis in Latin America was addressed by what came to be known as the Washington Consensus, which was articulated by John Williamson in 1989.[135] These principles were:

- Fiscal policy discipline, with avoidance of large fiscal deficits relative to GDP;

- Redirection of public spending from subsidies ("especially indiscriminate subsidies") toward broad-based provision of key pro-growth, pro-poor services like primary education, primary health care and infrastructure investment;

- Tax reform, broadening the tax base and adopting moderate marginal tax rates;

- Interest rates that are market determined and positive (but moderate) in real terms;

- Competitive exchange rates;

- Trade liberalization: liberalization of imports, with particular emphasis on elimination of quantitative restrictions (licensing, etc.); any trade protection to be provided by low and relatively uniform tariffs;

- Liberalization of inward foreign direct investment;

- Privatization of state enterprises;

- Deregulation: abolition of regulations that impede market entry or restrict competition, except for those justified on safety, environmental and consumer protection grounds, and prudential oversight of financial institutions;

- Legal security for property rights.

These principles focused on liberalization of trade policy, reduction of the role of the state, and fiscal orthodoxy. The term "Washington Consensus" implies that "the consensus comes or is imposed from Washington."[136]

Latin American governments undertook a series of structural reforms in the 1980s and 90s, including trade liberalization for must of Latin America and privatization, which were often made a condition of loans by the IMF and the World Bank. Chile, which had experienced the 1973 military coup and then years of dictatorial rule, implemented sweeping economic changes in the 1970s: stabilization (1975); privatization (1974–78); financial reform (1975); labor reform (1979); pension reform (1981). Mexico's economy had crashed in 1982, and it began shifting its long-term economic policies to reform finances in 1986, but even more significant change came under the government of Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1988–1994). Salinas sought Mexico's entry into the Canada-U.S. free trade agreement, so that liberalization of trade policies, privatization of state-owned companies, and legal security for property rights were essential if Mexico was to be successful. Changes in the 1917 Mexican Constitution were passed in 1992 that shifted the role of the Mexican state. Canada and the U.S., as well as Mexico entered into the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which came into effect in January 1994. Per capita income in Latin America during the 1990s grew at an annual rate of 1.7% approximately half the rate of the 1960s–1970s.[126]

Growth of rural population in this period resulted in migrations to cities, where job opportunities were better, and movement to other rural areas opened up by road construction. Landless peasant populations in the Amazon basin, Central America, southern Mexico, and the Chocó region of Colombia have occupied ecologically fragile areas.[137] The expansion of cultivation into new areas for agro-exports have resulted in environmental degradation, including soil erosion and loss of biodiversity.[138]

Economic cooperation and free trade agreements

With the formation in 1947 of the General Agreement of Tariffs and Trade (GATT), a framework was established to lower tariffs and increase trade between member countries. It eliminated differential treatment between individual nations, such as most favored nation status, and treated all member states equally. In 1995, GATT became the World Trade Organization (WTO) to meet the growing institutional needs of a deepening globalization. Although trade barriers fell with GATT and the WTO, the requirement that all member states be treated equally and the need for all to agree on terms meant that there were several rounds of negotiations. The Doha round most recent talks, have stalled. Many countries have established bi-lateral trade agreements and there has been a proliferation of them, dubbed the Spaghetti bowl effect.[139]

Free trade agreements in Latin America and countries outside the region were established in the twentieth century. Some were short-lived, such as Caribbean Free Trade Association (1958–1962), which was later expanded into the Caribbean Community. Dominican Republic–Central America Free Trade Agreement initially included only Central American nations (excluding Mexico) and the U.S., but was expanded to include the Dominican Republic. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was an expansion of the bilateral agreement between the U.S. and Canada, to include Mexico, coming into force in January 1994. Other agreements include Mercosur was established in 1991 by the Treaty of Asunción as a customs union, with member states of Argentina; Brazil; Paraguay; Uruguay and Venezuela (suspended since December 2016).[140] The Andean Community (Comunidad Andina, CAN) is a customs union comprising the South American countries of Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, originally established in 1969 as the Andean Pact, and then in 1996 as the Comunidad Andina. Mercosur and CAN are the two largest trade blocs in South America.

Following the 2016 election of Donald Trump in the United States, there have been negotiations on NAFTA, which will likely take into account changes in the economic situation since it came into effect in 1994. These include the "transnationalization of services and the rise of the so-called digital/data economy – including communications, informatics, digital and platform technology, e-commerce, financial services, professional and technical work, and a host of other intangible products."[141]

Migration and remittances

The migration of Latin Americans to areas with more prosperous economies has resulted meant the loss population across international borders, particularly the U.S. But the remittances of money to their non-migrating families represent an important infusion to the countries' economies. A report by the Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD) estimates for 2017 that remittances to Mexico would be $30.5 billion, Guatemala $8.7B; Dominican Republic $5.7B, Colombia $5.5B; and El Salvador $5.1B.[142]

Corruption

Corruption is a major problem for Latin American countries and affects their economies. According to Transparency International in its 2015 report ranking 167 countries by the perception of transparency, Uruguay ranked (21) the highest with 72% perception of transparency, with other major Latin American countries ranked considerably lower, Colombia rank 83/36%; Argentina 106/35%; Mexico 111/34%; and Venezuela the lowest at 158/19%.[143] The illegal drug trade, particularly of cocaine from the Andes that is transshipped throughout the hemisphere, generates huge profits. Money laundering of these black market funds is one result, often with the complicity of financial institutions and government officials. Violence from narcotrafficking has been significant in Colombia and Mexico.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, Steel. New York 1997.

- ↑ Rebecca Storey and Randolph J. Widmer, "The Pre-Columbian Economy" in The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America, vol. 1, New York: Cambridge University Press 2006,74.

- ↑ Lockhart and Schwartz, Early Latin America, New York: Cambridge University Press 1983, p. 59.