| Eleanor of Castile | |

|---|---|

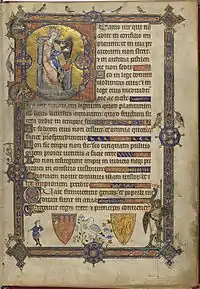

Tomb effigy of Eleanor at Lincoln Cathedral | |

| Queen consort of England | |

| Tenure | 20 November 1272 – 28 November 1290 |

| Coronation | 19 August 1274 |

| Countess of Ponthieu | |

| Reign | 16 March 1279 – 28 November 1290 |

| Predecessor | Joan |

| Successor | Edward II |

| Alongside | Edward I |

| Born | 1241 Burgos, Castile |

| Died | 28 November 1290 (aged 48–49) Harby, Nottinghamshire, England |

| Burial | 17 December 1290 Westminster Abbey, London, England |

| Spouse | |

| Issue more... | |

| House | Ivrea |

| Father | Ferdinand III of Castile |

| Mother | Joan, Countess of Ponthieu |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Eleanor of Castile (1241 – 28 November 1290) was Queen of England as the first wife of Edward I. She was well educated at the Castilian court. She also ruled as Countess of Ponthieu suo jure from 1279. After intense diplomatic manoevres to secure her marriage to affirm English sovereignty over Gascony, she was married to Prince Edward at the monastery of Las Huelgas, Burgos, on 1 November 1254, at 13. She is believed to have had a child not long after.

Eleanor's life with Edward is better recorded from the time of the Second Barons' War onwards, when she spent a time imprisioned in Westminster Palace by Simon de Montfort's government. She took an active role in Edward's reign as he began to take control of Henry III's government after the war. The marriage was particularly close, and they travelled together extensively, including on the Ninth Crusade during which Edward was wounded at Acre.[1][lower-alpha 1] She was capable of influencing politics but died too young to have a major impact.

In her lifetime, she was disliked for her property dealings, as she bought up vast lands such as Leeds Castle from the middling landed classes after they had fallen behind loan repayments to Jewish moneylenders forced to sell their bonds by the Crown. These transactions associated her with the abuse of usury and the supposed exploitation of Jews, bringing her into conflict with the church.[2][3][4][5] She profited from the hanging of over 300 supposed Jewish coin clippers.[6] and after the Expulsion of the Jews in 1290, gifted the former Cambridge Synagogue to her tailor.[7] When she died, at Harby near Lincoln in late 1290, Edward built a stone cross at each stopping-place on the journey to London, ending at Charing Cross. The sequence appears to have included the renovated tomb of Little St Hugh,[8] – falsely believed to have been ritually murdered by Jews – in order to bolster her reputation as an opponent of supposed Jewish criminality.[9][10][11]

Eleanor exerted a strong cultural influence. She was a keen patron of literature and encouraged the use of tapestries, carpets and tableware in the Spanish style, as well as innovative garden designs. She was a devoted patron of the Dominican friars,[12] founding priories in England and supporting their work at Oxford and Cambridge universities. Notwithstanding the sources of her wealth, her financial independence had a lasting impact on the institutional standing of English Queens, establishing their future independence of action. Her reputation after death was shaped by competing positive and negative fictitious accounts, portraying her as either the dedicated companion of Edward I, or a scheming Spaniard. These accounts influenced the fate of the Eleanor crosses, for which she is probably best known today. Only in recent decades has she begun to receive serious academic study.

Life

Birth

Eleanor was born in Burgos, daughter of Ferdinand III of Castile and Joan, Countess of Ponthieu.[13][14] Her Castilian name, Leonor, became Alienor or Alianor in England, and Eleanor in modern English. She was named after her paternal great-grandmother, Eleanor of England, the daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine and Henry II of England.

Eleanor was the second of five children born to Ferdinand and Joan. Her elder brother Ferdinand was born in 1239/40, her younger brother Louis in 1242/43; two sons born after Louis died young. For the ceremonies in 1291 marking the first anniversary of Eleanor's death, 49 candlebearers were paid to walk in the public procession to commemorate each year of her life. As the tradition was to have one candle for each year of the deceased's life, 49 candles would date Eleanor's birth to 1240 or 1241.

As her parents were apart from each other for 13 months while King Ferdinand was on a military campaign in Andalusia, from which he returned to the north of Spain only in February 1241, Eleanor was probably born towards the end of that year. The courts of her father and her half-brother Alfonso X of Castile were known for their literary atmosphere. Both kings also encouraged extensive education of the royal children, and it is therefore likely that Eleanor was educated to a standard higher than the norm, a likelihood which is reinforced by her later literary activities as queen.[15]

Prospective bride to Theobald II of Navarre

Eleanor's marriage in 1254 to the future Edward I of England was not the only marriage her family planned for her.[17]

The kings of Castile had long made a tenuous claim to be paramount lords of the Kingdom of Navarre due to sworn homage from Garcia VI of Navarre in 1134. In 1253, Ferdinand III's heir, Eleanor's half-brother Alfonso X of Castile, stalled negotiations with England in hopes that she would marry Theobald II of Navarre.

The marriage afforded several advantages. First, the Pyrenees kingdom also afforded passage from Castile to Gascony. Secondly, Theobald II was not yet of age, thus the opportunity existed to rule or potentially annex Navarre into Castile. To avoid Castilian control, Margaret of Bourbon (mother and regent to Theobald II) in August 1253 allied with James I of Aragon instead, and as part of that treaty, solemnly promised that Theobald would never marry Eleanor.

Marriage

In 1252, Alfonso X resurrected another ancestral claim, this time to the duchy of Gascony in the south of Aquitaine (the last possession of the Kings of England in France), which he claimed had formed part of the dowry of Eleanor of England. Henry III of England swiftly countered Alfonso's claims with both diplomatic and military moves. Early in 1253, the two kings began to negotiate; after haggling over the financial provision for Eleanor, Henry and Alfonso agreed she would marry Henry's son Edward (by now the titular duke), and Alfonso would transfer his Gascon claims to Edward. Henry was so anxious for the marriage to take place that he willingly abandoned elaborate preparations already made for Edward's knighting in England and agreed that Alfonso would knight Edward on or before the next Feast of Assumption.[15]

The young couple were married at the monastery of Las Huelgas, Burgos, on 1 November 1254. Edward and Eleanor were second cousins once removed, as Edward's grandfather King John of England and Eleanor's great-grandmother Eleanor of England were the son and daughter of King Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. Following the marriage they spent nearly a year in Gascony, with Edward ruling as lord of Aquitaine. During this time Eleanor, aged thirteen and a half, almost certainly gave birth to her first child, a short-lived daughter.[18] She journeyed to England alone in late summer of 1255. Edward followed her a few months later.[19]

Henry III took pride in resolving the Gascon crisis so decisively, but his English subjects feared that the marriage would bring Eleanor's kinfolk and countrymen to live off Henry's ruinous generosity. A few of her relatives did come to England soon after her marriage. She was too young to stop them or prevent Henry III from supporting them, but she was blamed anyway and her marriage soon became unpopular.

The presence of more English, French and Norman soldiers of fortune and opportunists in the cities of Seville and Cordoba, recently conquered from the Moorish Almohads, would be increased, however, thanks to this alliance between royal houses, until the advent of the later Hundred Years War, when it would be symptomatic of extended hostilities between the French and the English for peninsular support.

Second Barons' War

There is little record of Eleanor's life in England until the 1260s, when the Second Barons' War, between Henry III and his barons, divided the kingdom. During this time, Eleanor actively supported Edward's interests, importing archers from her mother's county of Ponthieu in France. It is untrue, however, that she was sent to France to escape danger during the war; she was in England throughout the struggle and held Windsor Castle and baronial prisoners for Edward. Rumours that she was seeking fresh troops from Castile led the baronial leader, Simon de Montfort, to order her removal from Windsor Castle in June 1264 after the royalist army had been defeated at the Battle of Lewes.

Edward was captured at Lewes and imprisoned, and Eleanor was confined at Westminster Palace. After Edward and Henry's army defeated the baronial army at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, Edward took a major role in reforming the government and Eleanor rose to prominence at his side. Her position was greatly improved in July 1266 when, after she had borne three short-lived daughters, she gave birth to a son, John, to be followed by a second boy, Henry, in the spring of 1268, and in June 1269 by a healthy daughter, Eleanor.

Crusade

Eleanor came from a family heavily involved in the Crusades. She appears to have been very committed to the church's call to arms, and took a vow to participate. Unlike men, women were not obliged to travel to fulfill their vow, and were discouraged from doing so, if not actually barred. Although other women members of her family had travelled on crusade, it was still an unusual thing to do.[20]

By 1270, England was at peace and Edward and Eleanor left to join his uncle Louis IX of France on the Eighth Crusade. Louis died at Carthage before they arrived, however, and after they spent the winter in Sicily, the couple went on to Acre in the Holy Land, where they arrived in May 1271. Eleanor gave birth to a daughter, known as "Joan of Acre" for her birthplace.[21]

The crusade was militarily unsuccessful, but Baibars of the Bahri dynasty was worried enough by Edward's presence at Acre that an assassination attempt was made on the English heir in June 1272.[1] He was wounded in the arm by a dagger that was thought to be poisoned. The wound soon became seriously inflamed, and a surgeon saved him by cutting away the diseased flesh, but only after Eleanor was led from his bed, "weeping and wailing".[22][lower-alpha 1]

They left Acre in September 1272, and in Sicily that December, they learned of Henry III's death (on 16 November 1272).[23] Following a trip to Gascony, where their next child, Alphonso (named for Eleanor's half brother Alfonso X), was born, Edward and Eleanor returned to England and were crowned together on 19 August 1274.

Queen consort of England

Arranged royal marriages in the Middle Ages were not always happy, but available evidence indicates that Eleanor and Edward were devoted to each other. Edward is among the few medieval English kings not known to have conducted extramarital affairs or fathered children out of wedlock. The couple were rarely apart; she accompanied him on military campaigns in Wales, famously giving birth to their son Edward on 25 April 1284 at Caernarfon Castle, either in a temporary dwelling erected for her amid the construction works, or in the partially constructed Eagle Tower.

Their household records witness incidents that imply a comfortable, even humorous, relationship. Each year on Easter Monday, Edward let Eleanor's ladies trap him in his bed and paid them a token ransom so he could go to her bedroom on the first day after Lent; so important was this custom to him that in 1291, on the first Easter Monday after Eleanor's death, he gave her ladies the money he would have given them had she been alive. Edward disliked ceremonies and in 1290 refused to attend the marriage of Earl Marshal Roger Bigod, 5th Earl of Norfolk; Eleanor thoughtfully (or resignedly) paid minstrels to play for him while he sat alone during the wedding.

That Edward remained single until he wedded Margaret of France in 1299 is often cited to prove he cherished Eleanor's memory. In fact, he considered a second marriage as early as 1293, but this does not mean he did not mourn Eleanor. Eloquent testimony is found in his letter to the abbot of Cluny in France (January 1291), seeking prayers for the soul of the wife "whom living we dearly cherished, and whom dead we cannot cease to love". In her memory, Edward ordered the construction of twelve elaborate stone crosses (of which three survive, though none of them is intact) between 1291 and 1294, marking the route of her funeral procession between Lincoln and London. (See § Procession, burial and monuments below.)

Only one of Eleanor's four sons survived childhood, however, and even before she died, Edward worried over the succession: if that son died, their daughters' husbands might cause a succession war. Despite personal grief, Edward faced his duty and married again. He delighted in the sons his new wife bore, but attended memorial services for Eleanor to the end of his life, Margaret at his side on at least one occasion.

Land acquisition and unpopularity

Eleanor's acquisition of lands was exceptional by any standard: between 1274 and 1290 she acquired estates worth about £2600 yearly.[12] In fact, it was Edward himself who initiated this process[12] and his ministers helped her. He wanted the queen to hold lands sufficient for her financial needs without drawing on funds needed for government.[12]

However, the main method for Eleanor to acquire land was the cheap purchase of the debts that Christian landlords owed Jewish moneylenders. In exchange for cancelling the debts, she received the lands pledged for the debts. Since the early 1200s, the Jewish community had been taxed well beyond its means, leading to a reduction in the capital the small number of rich Jewish moneylenders had to support their lending. Jews were also disallowed from holding land assets. To recoup against a defaulted debt, the bonds for the lands could be sold. However, these could only be bought and sold by Royal permission, meaning that Eleanor and a select group of very wealthy courtiers were the exclusive beneficiaries of these sales. The periodic excessive taxes of the Jews called "tallages" would force them to sell their bonds very cheaply to release their capital, and would be bought by courtiers.[2][3][24]

By the 1270s, this had led the Jewish community into a desperate position, while Edward, Eleanor and a few others gained vast new estates.[4] Contemporaries, however, saw the problem as resulting from Jewish "usury" which contributed to a rise in anti-Semitic beliefs. Her participation in "Jewish usury" and dispossession of middling landowners caused Eleanor to be criticised both by members of the landed classes and by the church.

It has been argued that debtors were often glad to rid themselves of the debts, and profited from the favour Eleanor showed them afterwards; she granted many of them, for life, lands worth as much as the estates they had surrendered to her, and some of them became her household knights.

A spectacular example of an estate picked up cheaply can be seen in the release of Leeds Castle to Edward and Eleanor by William de Leybourne, which became a favourite residence.[4]

Eleanor acquired an "unsavoury reputation".[4] Records of her unpopularity are common. For instance, Walter of Guisborough highlighted her reputation and preserves a contemporary poem:

The king would like to get our gold,

the queen, our manors fair, to hold …[5]

The annalist of Dunstable Priory echoed him in a contemporary notice of her death: "a Spaniard by birth, she acquired many fine manors".[25]

John Peckham, Archbishop of Canterbury warned Eleanor's servants about her activities in the land market and her association with the highly unpopular moneylenders: "A rumour is waxing strong throughout the kingdom and has generated much scandal. It is said that the illustrious lady queen, whom you serve, is occupying many manors, lands, and other possessions of nobles, and has made them her own property – lands which the Jews have extorted with usury from Christians under the protection of the royal court."[5]

Peckham also warned Eleanor of complaints against her officials' demands upon her tenants. She must have been aware of the truth of such reports since, on her deathbed, she asked Edward to name justices to examine her officials' actions and make reparations. The surviving proceedings from this inquest reveal a pattern of ruthless exactions, often (but not always) without Eleanor's knowledge. Her executors' financial accounts record the payments of reparations to many of those who brought actions before the judicial proceedings in 1291. It has been claimed that in her lifetime, Eleanor had righted such wrongs when she heard of them, and her deathbed request of Edward indicates that she knew, suspected, or feared, that her officials had perpetrated many more transgressions than were ever reported to her. Others interpret her deathbed actions as an admission of guilt, and an attempt to make amends before she met her judgment.

Other income

Eleanor had other kinds of income as Queen. She was granted significant income from anything hidden or unclaimed assets resulting from trials. For instance, during the late 1270s, Jews were targeted for coin-clipping offences. Although the evidence was largely fictional, around 10% of the Jewish population was sentenced to death, representing over 300 individuals. As a result, their assets were seized and forfeit to the Crown; together with fines for those who escaped hanging, over £16,500 was collected, from which Eleanor received a significant portion.[6]

Following the 1290 Edict of Expulsion, where the whole Jewish population of expelled from England, their houses, debts and other property was forfeit to the Crown. Around £2,000 was raised for the Crown from sales, but much was given away in about 85 grants to courtiers, friends and family, including the Synagogue at Cambridge, which Eleanor gave to her tailor.[7]

Political influence

It has traditionally been argued that Eleanor had no impact on the political history of Edward's reign, and that even in diplomatic matters her role was minor, though Edward did heed her advice on the age at which their daughters could marry foreign rulers. Otherwise, it has been said, she merely gave gifts, usually provided by Edward, to visiting princes or envoys. Edward always honoured his obligations to Alfonso X, but even when Alfonso's need was desperate in the early 1280s, Edward did not send English knights to Castile; he sent only knights from Gascony, which was closer to Castile.

Eleanor did played a role in Edward's counsels, although she did not exercise power overtly except on occasions where she was appointed to mediate disputes of a between nobles in England and Gascony. Some of Edward's legislation, for example the Statute of Jewry and his approach to Welsh resettlement show some similarities to Castilian approaches. His military strategies, too, appear to have been influenced by the work of Vegetius, to which Eleanor directed his attention when she commissioned an Old French translation while on Crusade in Acre in 1272.[23] She also intervened to defend the Earl of Cornwall in 1287 against charges of inompetence, arguing they were unjustified.[12] She was a "clever operator" at court, with "unique influence" given the love that Edward had for her.[12]

Edward was, however, clearly prepared to resist her demands, or to stop her, if he felt she was going too far in any of her activities, and that he expected his ministers to restrain her if her actions threatened to inconvenience important people in his realm, as happened on one occasion when Robert Burnell, the Lord Chancellor, assured the Bishop of Winchester, from whom the queen was demanding a sum of money the bishop owed her, that he would speak with the queen and that the business would end happily for the bishop.

Nevertheless, as queen, her major opportunity for power and influence would have been later in her life, when her sons grew older through promoting their political and military careers.[12]

Promotion of her relatives

.svg.png.webp)

She patronised many relatives, though given foreigners' unpopularity in England and the criticism of Henry III and Eleanor of Provence's generosity to them, she was cautious as queen to choose which cousins to support. Rather than marry her male cousins to English heiresses, which would put English wealth in foreign hands, she arranged marriages for her female cousins to English barons. Edward strongly supported her in these endeavours, which provided him and his family (and Eleanor herself, in her potential widowhood) with an expanded network of potential supporters.

In a few cases, her marriage projects for her lady cousins provided Edward, as well as her father-in-law Henry III, with opportunities to sustain healthy relations with other realms. The marriage of her kinswoman Marguerite de Guines to the earl of Ulster, one of the more influential English noblemen in Ireland, not only gave Edward a new family connection in that island but also with Scotland, since Marguerite's cousin Marie de Coucy was the mother of Edward's brother-in-law Alexander III. The earliest of Eleanor's recorded marriage projects linked one of her Châtellerault cousins with a member of the Lusignan family, Henry III's highly favoured maternal relatives, not only strengthening the king's ties with that family but also creating a new tie between the English king and a powerful family in Poitou, on Gascony's northern flank.

Cultural influence

If she was allowed no overt political role, Eleanor was a highly intelligent and cultured woman and found other satisfying outlets for her energies. She was an active patroness of literature, maintaining the only royal scriptorium known to have existed at the time in Northern Europe, with scribes and at least one illuminator to copy books for her. Some of the works produced were apparently vernacular romances and saints' lives, but Eleanor's tastes ranged far more widely than that and were not limited to the products of her own writing office. The number and variety of new works written for her show that her interests were broad and sophisticated. In the 1260s she commissioned the production of the Douce Apocalypse. She has also been credibly linked to the Trinity Apocalypse, although the question of whether she commissioned it, or simply owned an apocalypse which influenced its production, remains a matter of debate. On Crusade in 1272, she had De Re Militari by Vegetius translated for Edward.

After she succeeded her mother as countess of Ponthieu in 1279, a romance was written for her about the life of a supposed 9th century count of Ponthieu. She commissioned an Arthurian romance with a Northumbrian theme, possibly for the marriage of the Northumbrian lord John de Vescy, who married a close friend and relation of hers. In the 1280s, Archbishop Peckham wrote a theological work for her to explain what angels were and what they did. She almost certainly commissioned the Alphonso Psalter, now in the British Library, and is also suspected to be the commissioner of the Bird Psalter which also bears the arms of Alphonso and his prospective wife. In January 1286 she thanked the abbot of Cerne for lending her a book; possibly a treatise on chess known to have been written at Cerne in the late thirteenth century. Her accounts reveal her in 1290 corresponding with an Oxford master about one of her books. There is also evidence suggesting that she exchanged books with her brother Alfonso X.

Relevant evidence suggests that Eleanor was not fluent in English, but was accustomed to read, and so presumably to think and speak, in French, her mother's tongue, with which she would have been familiar from childhood despite spending her early years in Spain. In this she was luckier than many medieval European queens, who often arrived in their husband's realms to face the need to learn a new language; but the English court was still functionally bilingual, in large measure through the long succession of its queens, who were mostly from French-speaking lands. In 1275, on a visit to St Albans abbey in Hertfordshire, the people of the town begged her help in withstanding the abbot's exactions from them, but one of her courtiers had to act as translator before she could respond to the plea for assistance. All the literary works noted above are in French, as are the bulk of her surviving letters, and since Peckham wrote his letters and his angelic treatise for her in French, she was presumably well known to prefer that language.

In the domestic sphere she popularised the use of tapestries and carpets – the use of hangings and especially floor coverings was noted as a Spanish extravagance on her arrival in London, but by the time of her death was plainly much in vogue amongst richer magnates, with certain of her hangings having to be reclaimed from Anthony Bek, the bishop of Durham. She also promoted the use of fine tableware, elegantly decorated knives, and even forks (though it remains uncertain whether the latter were used as personal eating utensils or as serving pieces from the common bowls or platters). She also had considerable influence on the development of garden design in the royal estates. Extensive spending on gardens is evidenced at her properties and in most places she stayed, including the use of water features – a common Castilian garden design feature, which was owed to Islamic and Roman influences in Spain. The picturesque Gloriette at Leeds Castle was developed during her ownership of the castle.

Religious views and patronage

The queen was a devoted patron of the Dominican Order friars,[12] founding several priories in England and supporting their work at the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge. Not surprisingly, then, Eleanor's piety was of an intellectual stamp; apart from her religious foundations she was not given to direct good works, and she left it to her chaplains to distribute alms for her. Her level of charitable giving was, however, considerable.

Eleanor as a mother

It has been suggested that Eleanor and Edward were more devoted to each other than to their children. As king and queen, however, it was impossible for them to spend much time in one place, and when the children were very young, they could not tolerate the rigors of constant travel with their parents. The children had a household staffed with attendants carefully chosen for competence and loyalty, with whom the parents corresponded regularly. The children lived in this comfortable establishment until they were about seven years old; then they began to accompany their parents, if at first only on important occasions.

By their teens the children were with the king and queen much of the time. In 1290, Eleanor sent one of her scribes to join her children's household, presumably to help with their education. She also sent gifts to the children regularly, and arranged for the entire establishment to be moved near to her when she was in Wales. In 1306 Edward sharply scolded Margerie de Haustede, Eleanor's former lady in waiting who was then in charge of his children by his second wife, because Margerie had not kept him well informed of their health. Edward also issued regular and detailed instructions for the care and guidance of these children.

Two incidents cited to imply Eleanor's lack of interest in her children are easily explained in the contexts of medieval royal childrearing in general, and of particular events surrounding Edward and Eleanor's family. When their six-year-old son Henry lay dying at Guildford in 1274, neither parent made the short journey from London to see him; but Henry was tended by Edward's mother Eleanor of Provence. The boy had lived with his grandmother while his parents were absent on crusade, and since he was barely two years old when they left England in 1270, he could not have had many substantial memories of them at the time they returned to England in August 1274, only weeks before his last illness and death. In other words, the dowager queen was a more familiar and comforting presence to her grandson than his parents would have been at that time, and it was in all respects better that she tended him then. Furthermore, Eleanor was pregnant at the time of his final illness and death; even given the limited thirteenth-century understanding of contagion, exposure to a sickroom might have been discouraged.

Similarly, Edward and Eleanor allowed her mother, Joan, Countess of Ponthieu, to raise their daughter Joan of Acre in Ponthieu (1274–1278). This implies no parental lack of interest in the girl; the practice of fostering noble children in other households of sufficient dignity was not unknown and Eleanor's mother was, of course, dowager queen of Castile. Her household was safe and dignified, but it does appear that Edward and Eleanor had cause to regret their generosity in letting Joan of Ponthieu foster young Joan. When the girl reached England in 1278, aged six, it turned out that she was badly spoiled. She was spirited and at times defiant in childhood, and in adulthood remained a handful for Edward, defying his plans for a prestigious second marriage for her by secretly marrying one of her late first husband's squires.

When the marriage was revealed in 1297 because Joan was pregnant, Edward was enraged that his dignity had been insulted by her marriage to a commoner of no importance. Joan, at twenty-five, reportedly defended her conduct to her father by saying that nobody saw anything wrong if a great earl married a poor woman, so there could be nothing wrong with a countess marrying a promising young man. Whether or not her retort ultimately changed his mind, Edward restored to Joan all the lands he had confiscated when he learned of her marriage, and accepted her new husband as a son-in-law in good standing. Joan marked her restoration to favour by having masses celebrated for the soul of her mother Eleanor.

Character

Two letters from Peckham show that some people thought she urged Edward to rule harshly and that she could be a severe woman who did not take it lightly if any one crossed her, which contravened contemporary expectations that queens should intercede with their husbands on behalf of the needy, the oppressed, or the condemned.[26]

Thus, he warned a convent of nuns that "if they knew what was good for them", they would accede to the queen's wishes and accept into their house a woman the convent had refused, but whose vocation Eleanor had decided to sponsor. Record evidence from the king's administrations shows that Hugh Despenser the Elder, who agreed to allow the queen to hold one of his manors for a term of years in order to clear his debt to her, thought it well to demand official assurances from the King's Exchequer that the manor would be restored to him as soon as the queen had recovered the exact amount of the debt.

It is only with a chronicle written at St Albans in 1307–08 that we find the first positive assessment of her character, and it is hard to avoid the impression that the chronicler was writing to flatter her son, Edward II, who had succeeded his father in 1307.

Death of Eleanor

Eleanor was presumably a healthy woman for most of her life; that she survived at least sixteen pregnancies suggests that she was not frail. Shortly after the birth of her last child, however, financial accounts from Edward's household and her own begin to record frequent payments for medicines to the queen's use. The nature of the medicines is not specified, so it is impossible to know what ailments were troubling her until, later in 1287 while she was in Gascony with Edward, a letter to England from a member of the royal entourage states that the queen had a double quartan fever. This fever pattern suggests that she was suffering from a strain of malaria. The disease is not fatal of itself, but leaves its victims weak and vulnerable to opportunistic infections. Among other complications, the liver and spleen become enlarged, brittle, and highly susceptible to injury which may cause death from internal bleeding. There is also a possibility that she had inherited the Castilian royal family's theorised tendency to cardiac problems.

From the time of the return from Gascony there are signs that Eleanor was aware that her death was not far off. Arrangements were made for the marriage of two of her daughters, Margaret and Joan, and negotiations for the marriage of young Edward of Caernarfon to Margaret, the Maid of Norway, heiress of Scotland, were hurried on. In summer 1290, a tour north through Eleanor's properties was commenced, but proceeded at a much slower pace than usual, and the autumn Parliament was convened in Clipstone, rather than in London.[27] Eleanor's children were summoned to visit her in Clipstone, despite warnings that travel might endanger their health. Following the conclusion of the parliament Eleanor and Edward set out the short distance from Clipstone to Lincoln. By this stage Eleanor was travelling fewer than eight miles a day.

Her final stop was at the village of Harby, Nottinghamshire, less than 7 miles (11 km) from Lincoln.[28] The journey was abandoned, and the queen was lodged in the house of Richard de Weston, the foundations of which can still be seen near Harby's parish church. After piously receiving the Church's last rites, she died there on the evening of 28 November 1290, aged 49 and after 36 years of marriage. Edward was at her bedside to hear her final requests. For three days afterward, the machinery of government came to a halt and no writs were sealed.

Procession, burial and monuments

Eleanor's embalmed body was borne in great state from Lincoln to Westminster Abbey, through the heartland of Eleanor's properties and accompanied for most of the way by Edward, and a substantial cortege of mourners. Edward gave orders that memorial crosses be erected at the site of each overnight stop between Lincoln and Westminster. Based on crosses in France marking Louis IX's funeral procession, these artistically significant monuments enhanced the image of Edward's kingship as well as witnessing his grief. The "Eleanor crosses" stood at Lincoln, Grantham, Stamford, Geddington, Hardingstone near Northampton, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St Albans, Waltham, Westcheap, and Charing – only three survive, none in its entirety. The best preserved is that at Geddington. All three have lost the crosses "of immense height" that originally surmounted them; only the lower stages remain. The top (cross) part of the Hardingstone monument is believed to reside in the Northampton Guildhall Museum. The Waltham cross has been heavily restored and to prevent further deterioration, its original statues of the queen are now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

The monument now known as "Charing Cross" in London, in front of the railway station of that name, was built in 1865 to publicise the railway hotel at Charing station. The original Charing cross was at the top of Whitehall, on the south side of Trafalgar Square, but was destroyed in 1647 and later replaced by a statue of Charles I.

In the thirteenth century, embalming involving evisceration and separate burial of heart and body was not unusual. Eleanor however was afforded the more unusual "triple" burial – separate burial of viscera, heart and body. Eleanor's viscera were buried in Lincoln Cathedral, where Edward placed a duplicate of the Westminster tomb. The Lincoln tomb's original stone chest survives; its effigy was destroyed in the 17th century and has been replaced with a 19th-century copy.[lower-alpha 2]

Also built in the same style with the Eleanor crosses and Eleanor's tomb at Lincoln was the renovated shrine of Little Saint Hugh,[8] a cult based on a false ritual murder allegation made against Jews. It is likely that the association with Eleanor was made in order to help improve her posthumous reputation, as she had been closely associated with the abuse of Jewish loans.[9][11] The crosses and tomb amounted to a "propaganda coup" rehabilitating Eleanor's image and portraying her as the protector of Chritians against the supposed criminality of Jews, in the wake of the Expulsion of the Jewry.[10]

The queen's heart was buried in the Dominican priory at Blackfriars in London, along with that of her son Alphonso. The accounts of her executors show that the monument constructed there to commemorate her heart burial was richly elaborate, including wall paintings as well as an angelic statue in metal that apparently stood under a carved stone canopy. It was destroyed in the 16th century during the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Eleanor's funeral took place in Westminster Abbey on 17 December 1290. Her body was placed in a grave near the high altar that had originally contained the coffin of Edward the Confessor and, more recently, that of King Henry III until his remains were removed to his new tomb in 1290. Eleanor's body remained in this grave until the completion of her own tomb. She had probably ordered that tomb before her death. It consists of a marble chest with carved mouldings and shields (originally painted) of the arms of England, Castile, and Ponthieu. The chest is surmounted by William Torel's superb gilt-bronze effigy, showing Eleanor in the same pose as the image on her great seal.

When Edward remarried a decade after her death, he and his second wife Margaret of France, named their only daughter Eleanor in honour of her.

Legacy

Notwithstanding the manner by which she acquired her estates and income, Eleanor of Castile's queenship is significant in English history for the evolution of a stable financial system for the king's wife, and for the honing this process gave the queen-consort's prerogatives. The estates Eleanor assembled became the nucleus for dower assignments made to later queens of England into the 15th century, and her involvement in this process established a queen-consort's freedom to engage in such transactions.

Historical reputation

Despite her negative reputation in her own day, the St Albans Chronicle and the Eleanor Crosses assured Eleanor a romantic and flattering, if slightly obscure, standing over the next two centuries. As late as 1586, the antiquarian William Camden first published in England the tale that Eleanor saved Edward's life at Acre by sucking his wound. Camden then went on to ascribe construction of the Eleanor crosses to Edward's grief at the loss of an heroic wife who had selflessly risked her own life to save his.[lower-alpha 3] A year later in 1587, Raphael Holinshed's Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland described Eleanor as "the jewel [Edward I] most esteemed ... a godly and modest princess, full of pity, and one that showed much favour to the English nation, ready to relieve every man's grief that sustained wrong and to make them friends that were at discord, so far as in her lay."[30]

But a counter-narrative, driven by rising anti-Spanish feeling in England from the Reformation onwards, may already have begun to emerge. The Lamentable Fall of Queene Elenor, a popular ballad sung to the popular tune "Gentle and Courteous", is thought to date from as early as the 1550s, and to be an indirect attack on the half-Spanish queen Mary Tudor and her husband the Spanish Philip II of Spain.[31][lower-alpha 4] It depicts Eleanor as vain and violent: she demands of the king "that ev'ry man / That ware long lockes of hair, / Might then be cut and polled all"; she orders "That ev'ry womankind should have/Their right breast cut away"; she imprisons and tortures the Lady Mayoress of London, eventually murdering the Mayoress with poisonous snakes; she blasphemes against God on the common ground at Charing, causing the ground to swallow her up; and finally, miraculously spat up by the ground at Queen's Hithe, and now on her death-bed, she confesses not only to murder of the Mayoress but also to committing infidelity with a friar, by whom she has borne a child.[32]

This was followed in the 1590s by George Peele's The Famous Chronicle of King Edward the First. The first version of this, written in the early 1590s, is thought to have presented a positive depiction of the relationship between Eleanor and Edward. If so, it sank with little trace. The surviving revised version, as printed in 1593, depicts a haughty Eleanor as "a villainess capable of unspeakable treachery, cruelty, and depravity"; intransigent and hubristic, "concerned primarily with enhancing the reputation of her native nation, and evidently accustomed to a tyrannous and quite un-English exercise of royal prerogative"; delaying her coronation for twenty weeks so she can have Spanish dresses made, and proclaiming she shall keep the English under a "Spanish yoke". The misdeeds attributed to her in The Lamentable Fall of Queene Elenor are repeated and expanded upon: Eleanor is now also shown to box her husband's ears; and she now confesses to adultery with her own brother-in-law Edmund Crouchback and to conceiving all her children, bar Edward I's heir Edward II, in adultery – which revelation prompts her unfortunate daughter Joan of Acre, fathered by a French friar, to drop dead of shame. This is a portrait of Eleanor that owes little to historicity, and much to the then-current war with Spain, and English fears of a repeat attempt at invasion, and is one of a number of anti-Spanish polemic of the period.[33][31][34]

It would appear likely Peele's play, and the ballad associated with it, had a significant effect on the survival of the Eleanor Crosses in the 17th century. Performances of the play and reprints of The Lamentable Fall (it was reprinted in 1628, 1629, 1658, and 1664, testifying to its continuing popularity) meant that by the time of the Civil War this entirely hostile portrait of Eleanor was probably more widely known than the positive depictions by Camden and Hollingshed. The loss of most of the crosses can be documented or inferred to have been lost in the years 1643–1646: for example Parliament's Committee for the Demolition of Monuments of Superstition and Idolatry ordered the Charing Cross torn down in 1643. Eleanor's reputation however began to change for the positive once again at this time, following the 1643 publication of Sir Richard Baker's A History of the Kings of England, which retold the myth of Eleanor saving her husband at Acre. Thereafter, Eleanor's reputation was largely positive and derived ultimately from Camden, who was uncritically repeated wholesale by historians. In the 19th century the self-styled historian Agnes Strickland used Camden to paint the rosiest of all pictures of Eleanor. None of these writers, however, used contemporary chronicles or records to provide accurate information about Eleanor's life.[33][31]

Such documents began to become widely available in the late 19th century, but even when historians began to cite them to suggest Eleanor was not the perfect queen Strickland praised, many rejected the correction, often expressing indignant disbelief that anything negative was said about Eleanor. Only in recent decades have historians studied queenship in its own right and regarded medieval queens as worthy of attention. These decades produced a sizeable body of historical work that allows Eleanor's life to be scrutinised in the terms of her own day, not those of the 17th or 19th century.

The evolution of her reputation is a case study in the maxim that each age creates its own history. If Eleanor of Castile can no longer be seen as Peele's transgressive monstrosity, nor as Strickland's paradigm of queenly virtues, her career can now be examined as the achievement of an intelligent and determined woman who was able to meet the challenges of an exceptionally demanding life.

Issue

- Stillborn girl (July 1255)

- Katherine (c. 1264 – 5 September 1264), buried in Westminster Abbey.

- Joanna (January 1265 – before 7 September 1265), buried in Westminster Abbey.

- John (13 July 1266 – 3 August 1271), died at Wallingford, in the custody of his granduncle, Richard, Earl of Cornwall. Buried in Westminster Abbey.

- Henry (before 6 May 1268 – 16 October 1274), buried in Westminster Abbey.

- Eleanor (18 June 1269 – 29 August 1298). She was long betrothed to Alfonso III of Aragon, who died in 1291 before the marriage could take place, and in 1293 she married Count Henry III of Bar, by whom she had one son and two daughters.

- Daughter (1271 Palestine). Some sources call her Juliana, but there is no contemporary evidence for her name.

- Joan (April 1272 – 7 April 1307). She married (1) in 1290 Gilbert de Clare, 6th Earl of Hertford, who died in 1295, and (2) in 1297 Ralph de Monthermer, 1st Baron Monthermer. She had four children by each marriage.

- Alphonso (24 November 1273 – 19 August 1284), Earl of Chester.

- Margaret (15 March 1275 – after 1333). In 1290 she married John II of Brabant, who died in 1318. They had one son.

- Berengaria (1 May 1276 – before 27 June 1278), buried in Westminster Abbey.

- Daughter (December 1277/January 1278 – January 1278), buried in Westminster Abbey. There is no contemporary evidence for her name.

- Mary (11 March 1279 – 29 May 1332), a Benedictine nun in Amesbury.

- Son, born in 1280 or 1281 who died very shortly after birth. There is no contemporary evidence for his name.

- Elizabeth (7 August 1282 – 5 May 1316). She married (1) in 1297 John I, Count of Holland, (2) in 1302 Humphrey de Bohun, 4th Earl of Hereford and 3rd Earl of Essex. The first marriage was childless; by Bohun, Elizabeth had ten children.

- Edward II of England, also known as Edward of Caernarvon (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327). In 1308 he married Isabella of France. They had two sons and two daughters.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Later storytellers embellished this incident, creating a popular story of her saving his life by sucking out the poison, but this has long been discredited.

- ↑ On the outside of Lincoln Cathedral are two statues often identified as Edward and Eleanor, but these images were heavily restored and given new heads in the 19th century; probably they were not originally intended to depict the couple.[29]

- ↑ See Griffin 2009, p. 52 Camden's discussion of the crosses reflected the religious history of his time. The crosses were in fact meant to induce passers-by to pray for Eleanor's soul, but the Protestant Reformation in England had officially ended the practice of praying for the souls of the dead, so Camden ascribed Edward's commemoration of his wife to her alleged heroism in saving Edward's life at the risk of her own.

- ↑ The first printing of this ballad is from 1600, ten years after George Peele's Edward I was first performed; but the ballad in oral form is considered likely to date to the reign of Mary. Griffin 2009, p. 56; Cockerill 2014

Citations and references

- 1 2 Hamilton 1995, p. 100.

- 1 2 Stacey 1997, pp. 93–94.

- 1 2 Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, pp. 360–65.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Morris 2009, p. 225.

- 1 2 Rokéah 1988, p. 91-92.

- 1 2 Huscroft 2006, pp. 157–9.

- 1 2 David Stocker 1986.

- 1 2 Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, p. 658.

- 1 2 Hillaby 1994, p. 94-98.

- 1 2 Stacey 2001, p. 174.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Carpenter 2004, p. 468.

- ↑ Hamilton 1996, p. 92.

- ↑ Powicke 1991, p. 235.

- 1 2 Cockerill 2014, p. 80

- ↑ Parsons 1995, p. 9.

- ↑ Cockerill 2014, pp. 78, 79.

- ↑ Cockerill 2014, p. 90.

- ↑ Cockerill 2014, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Hamilton 1995, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Hamilton 1995, p. 93-100.

- ↑ The Chronicle of Walter of Guisborough. pp. 208–210.

- 1 2 Hamilton 1995, p. 101.

- ↑ Carpenter 2004, p. 490.

- ↑ Morris 2009, p. 229.

- ↑ Morris 2009, pp. 229–230.

- ↑ Cockerill 2014.

- ↑ Stevenson 1888, pp. 315–318.

- ↑ lincolnian 2006.

- ↑ Holinshed, Raphael, Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland; quoted in Griffin 2009, p. 52

- 1 2 3 Cockerill 2014

- ↑ Griffin 2009, p. 56.

- 1 2 Fuchs & Weissbourd 2015

- ↑ Griffin 2009, pp. 53–57.

Sources

Eleanor of Castile

- Armstrong, A.S. (2023). "Eleanor of Castile: A Consort of Contradictions". In Norrie, A.; Harris, C.; Laynesmith, J.; Messer, D.R.; Woodacre, E (eds.). Norman to Early Plantagenet Consorts. Queenship and Power. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 237–255. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-21068-6_13. ISBN 978-3-031-21067-9.

- Cockerill, Sara (2014). Eleanor of Castile: the shadow queen. Stroud: Amberley. ISBN 9781445635897.

- Dilba, Carsten (2009). Memoria Reginae: Das Memorialprogramm für Eleonore von Kastilien. Hildesheim.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hilton, Lisa (2009). "Eleanor of Castile". Queens consort : the autobiography. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-2611-9. OCLC 359673870.

- Parsons, John Carmi (1995). Eleanor of Castile: Queen and Society in Thirteenth Century England.

- Parsons, John Carmi (1997). "Mothers, Daughters, Marriage, Power: Some Plantagenet Evidence, 1150-1500". In Parsons, John Carmi (ed.). Medieval Queenship. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 63–78. ISBN 978-0312172985.

- Parsons, John Carmi (1984). "The Year of Eleanor of Castile's Birth and Her Children by Edward I". Mediaeval Studies. 46: 245–265. doi:10.1484/J.MS.2.306316. esp. 246 n. 3.

- Parsons, John Carmi (1998). "Que nos lactauit in infancia': The Impact of Childhood Care-givers on Plantagenet Family Relationships in the Thirteenth and Early Fourteenth Centuries". In Rousseau and, Constance M.; Rosenthal, Joel T. (eds.). Women, Marriage, and Family in Medieval Christendom: Essays in Memory of Michael M. Sheehan, C.S.B. Kalamazoo. pp. 289–324.

- Stevenson, W. H. (1 January 1888). "The Death of Queen Eleanor of Castile". The English Historical Review. 3 (10): 315–318. JSTOR 546367.

General history

- Carpenter, David (2004). The Struggle for Mastery: The Penguin History of Britain 1066–1284. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-1401-4824-4. OL 7348814M.

- Morris, Marc (2009). A Great and Terrible King: Edward I and the Forging of Britain. London: Windmill Books. ISBN 978-0-0994-8175-1.

- Powicke, Frederick Maurice (1991). The Thirteenth Century, 1216–1307. Oxford University Press.

Renaissance

- Fuchs, Barbara; Weissbourd, Emily, eds. (2015). Representing Imperial Rivalry in the Early Modern Mediterranean. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-4902-6. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt14bth82.

- Griffin, Eric J. (2009). English Renaissance Drama and the Specter of Spain: Ethnopoetics and Empire. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4170-9. JSTOR j.ctt3fh8z6.

- Hamilton, Bernard (1996). "Eleanor of Castile and the Crusading Movement". In Arbel, Benjamin (ed.). Intercultural Contacts in the Medieval Mediterranean. Frank Cass.

Eleanor and the Crusades

- Hamilton, B. (1995). "Eleanor of Castile and the Crusading Movement". Mediterranean Historical Review. 10 (1–2): 92-103. doi:10.1080/09518969508569686.

- Reynolds, Gordon (2023). "Proxy over Pilgrimage: Queen Eleanor of Castile and the Celebration of Crusade upon her Funerary Monument(s)". Peregrinations. 8 (4): 117–39.

Finances and anti-semitism

- Hillaby, Joe (1994). "The ritual-child-murder accusation: its dissemination and Harold of Gloucester". Jewish Historical Studies. 34: 69–109. JSTOR 29779954.

- Hillaby, Joe; Hillaby, Caroline (2013). The Palgrave Dictionary of Medieval Anglo-Jewish History. Basingstok: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230278165.

- Huscroft, Richard (2006). Expulsion: England's Jewish solution. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-752-43729-3. OL 7982808M.

- Rokéah, Zefira Entin (1988). "Money and the hangman in late thirteenth century England: Jews, Christians and coinage offences alleged and real (Part I)". Jewish Historical Studies. 31: 83–109. JSTOR 29779864.

- Stacey, Robert C. (1997). "Parliamentary Negotiation and the Expulsion of the Jews from England". In Prestwich, Michael; Britnell, Richard H.; Frame, Robin (eds.). Thirteenth Century England: Proceedings of the Durham Conference, 1995. Vol. 6. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 77–102. ISBN 978-0-85115-674-3.

- Stacey, Robert (2001). "Anti-Semitism and the Medieval English State". In Maddicott, J. R.; Pallister, D. M. (eds.). The Medieval State: Essays Presented to James Campbell. London: The Hambledon Press. pp. 163–77.

- David Stocker (1986). "The Shrine of Little St Hugh". Medieval Art and Architecture at Lincoln Cathedral. British Archaeological Association. pp. 109–117. ISBN 978-0-907307-14-3.

- Stokes, H. P. (1915–1917). "The relationship between the Jews and the Royal family of England in the Thirteenth century". Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England. Jewish Historical Society of England. 8: 153–170. JSTOR 29777686.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Tolan, John (2023). England's Jews: Finance, Violence, and the Crown in the Thirteenth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-1512823899. OL 39646815M.

Web sources

- Cockerill, Sara. "Eleanor of Castile's Final Journey". Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- lincolnian (24 March 2006). "Edward & Eleanor, Lincoln Cathedral".