Seville

Sevilla | |

|---|---|

Flag .svg.png.webp) Coat of arms | |

| Motto: NO8DO ([Ella] No me ha dejado – [She] has not abandoned me) | |

Location of Seville | |

| Coordinates: 37°23′24″N 5°59′24″W / 37.39000°N 5.99000°W | |

| Country | |

| Autonomous Community | |

| Province | Seville |

| Government | |

| • Type | Ayuntamiento |

| • Body | Ayuntamiento de Sevilla |

| • Mayor | José Luis Sanz (PP) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 140 km2 (50 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 7 m (23 ft) |

| Population (2021) | |

| • Municipality | 684,234 |

| • Rank | 4th |

| • Density | 4,900/km2 (13,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,100,000[1] |

| • Metro | 1,519,639 |

| Demonym(s) | Sevillan, Sevillian sevillano (m.), sevillana (f.) hispalense |

| GDP | |

| • Metro | €36.785 billion (2020) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postcode | 41001–41020, 41070–41071, 41080, 41092 |

| Website | www |

Seville (/səˈvɪl/ sə-VIL; Spanish: Sevilla, pronounced [seˈβiʎa] ⓘ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula.

Seville has a municipal population of about 701,000 as of 2022, and a metropolitan population of about 1.5 million, making it the largest city in Andalusia, the fourth-largest city in Spain and the 26th most populous municipality in the European Union. Its old town, with an area of 4 square kilometres (2 sq mi), contains a UNESCO World Heritage Site comprising three buildings: the Alcázar palace complex, the Cathedral and the General Archive of the Indies. The Seville harbour, located about 80 kilometres (50 miles) from the Atlantic Ocean, is the only river port in Spain.[3] The capital of Andalusia features hot temperatures in the summer, with daily maximums routinely above 35 °C (95 °F) in July and August.

Seville was founded as the Roman city of Hispalis. Known as Ishbiliyah after the Islamic conquest in 711, Seville became the centre of the independent Taifa of Seville following the collapse of the Caliphate of Córdoba in the early 11th century; later it was ruled by Almoravids and Almohads until being incorporated to the Crown of Castile in 1248.[4] Owing to its role as gateway of the Spanish Empire's trans-atlantic trade, managed from the Casa de Contratación, Seville became one of the largest cities in Western Europe in the 16th century. Coinciding with the Baroque period, the 17th century in Seville represented the most brilliant flowering of the city's culture; then began a gradual economic and demographic decline as silting in the Guadalquivir forced the trade monopoly to relocate to the nearby port of Cádiz.

The 20th century in Seville saw the tribulations of the Spanish Civil War, decisive cultural milestones such as the Ibero-American Exposition of 1929 and Expo '92, and the city's election as the capital of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia.

Name

Other names

Hisbaal is the oldest name for Seville. It appears to have originated during the Phoenician colonisation of the Tartessian culture in south-western Iberia and it refers to the god Baal.[5] According to Manuel Pellicer Catalán, the ancient name was Spal, and it meant "lowland" in the Phoenician language (cognate to the Hebrew Shfela and the Arabic Asfal أسفل).[6][7] During Roman rule, the name was Latinised as Hispal and later as Hispalis. After the Umayyad invasion, this name remained in use among the Mozarabs,[8] being adapted into Arabic as Išbīliya (إشبيلية): since the /p/ phoneme does not exist in Arabic, it was replaced by /b/; the Latin place-name suffix -is was Arabized as -iya, and a /æ/ turned into ī /iː/ due to the phonetic phenomenon called imāla.[9]

In the meantime, the city's official name had been changed to Ḥimṣ al-Andalus (حمص الأندلس), in reference to the city of Homs in modern Syria, the jund of which Seville had been assigned to upon the Umayyad conquest;[10][11][8][12] "Ḥimṣ al-Andalus" remained a customary and affectionate name for the city during the whole period throughout the Muslim Arab world,[8][13][14] being referred to for example in the encyclopedia of Yaqut al-Hamawi[15] or in Abu al-Baqa ar-Rundi's Ritha' al-Andalus.[16]

The city is sometimes referred to as the "Pearl of Andalusia".

The inhabitants of the city are known as sevillanos (feminine form: sevillanas) or hispalenses, after the Roman name of the city.

Motto

NO8DO is the official motto of Seville, popularly believed to be a rebus signifying the Spanish No me ha dejado, meaning "She [Seville] has not abandoned me". The phrase, pronounced with synalepha as [no ma ðeˈxaðo] no-madeja-do, is written with an eight in the middle representing the word madeja [maˈðexa] "skein [of wool]". Legend states that the title was given by King Alfonso X, who was resident in the city's Alcázar and supported by the citizens when his son, later Sancho IV of Castile, tried to usurp the throne from him.

The emblem is present on Seville's municipal flag, and features on city property such as manhole covers, and Christopher Columbus's tomb in the cathedral.

History

Seville is approximately 2,200 years old. The passage of the various civilizations instrumental in its growth has left the city with a distinct personality, and a large and well-preserved historical centre.

Early periods

.jpg.webp)

The mythological founder of the city is Hercules (Heracles), commonly identified with the Phoenician god Melqart, who the myth says sailed through the Strait of Gibraltar to the Atlantic, and founded trading posts at the current sites of Cádiz and of Seville.[17] The original core of the city, in the neighbourhood of the present-day street, Cuesta del Rosario, dates to the 8th century BC,[18] when Seville was on an island in the Guadalquivir.[19] Archaeological excavations in 1999 found anthropic remains under the north wall of the Real Alcázar dating to the 8th–7th century BC.[20] The town was called Hisbaal by the Phoenicians and by the Tartessians, the indigenous pre-Roman Iberian people of Tartessos, who controlled the Guadalquivir Valley at the time.

The city was known from Roman times as Hispal and later as Hispalis. Hispalis developed into one of the great market and industrial centres of Hispania, while the nearby Roman city of Italica (present-day Santiponce, birthplace of the Roman emperors Trajan and Hadrian)[21] remained a typically Roman residential city. Large-scale Roman archaeological remains can be seen there and at the nearby town of Carmona as well.

Existing Roman features in Seville itself include the remains exposed in situ in the underground Antiquarium of the Metropol Parasol building, the remnants of an aqueduct, three pillars of a temple in Mármoles Street, the columns of La Alameda de Hércules and the remains in the Patio de Banderas square near the Seville Cathedral. The walls surrounding the city were originally built during the rule of Julius Caesar, but their current course and design were the result of Moorish reconstructions.[22]

Following Roman rule, there were successive conquests of the Roman province of Hispania Baetica by the Germanic Vandals, Suebi and Visigoths during the 5th and 6th centuries.

Middle Ages

In the wake of the Islamic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, Seville (Spalis) was seemingly taken by Musa ibn Nusayr in the late summer of 712, while he was on his way to Mérida.[23] Yet it had to be retaken in July 713 by troops led by his son Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa, as the Visigothic population who had fled to Beja had returned to Seville once Musa left for Mérida.[23] The seat of the Wali of Al-Andalus (administrative division of the Umayyad Caliphate) was thus established in the city until 716,[23] when the capital of Al-Andalus was relocated to Córdoba.[24]

Seville (Ishbīliya) was sacked by Vikings in the mid-9th century. After Vikings arrived by 25 September 844, Seville fell to invaders on 1 October, and they stood for 40 days before they fled from the city.[25] During Umayyad rule, under an Andalusi-Arab framework, the bulk of the population were Muladi converts, to which Christian and Jewish minorities added up.[26] Up until the arrival of the Almohads in the 12th century, the city remained as the see of a Metropolitan Archbishop,[27] the leading Christian religious figure in al-Andalus. However, the transfer of the relics of Saint Isidore to León circa 1063, in the taifa period, already hinted at a possible worsening of the situation of the local Christian minority.[28]

A powerful taifa kingdom with capital in Seville emerged after 1023,[29] in the wake of the fitna of al-Andalus. Ruled by the Abbadid dynasty, the taifa grew by aggregation of smaller neighbouring taifas.[29] During the taifa period, Seville became an important scholarly and literary centre.[29] After several months of siege, Seville was conquered by the Almoravids in 1091.[30]

The city fell to the Almohads on 17 January 1147 (12 Shaʽban 541).[31][32] After an informal Almohad settlement in Seville during the early stages of the Almohad presence in the Iberian Peninsula and then a brief relocation of the capital of al-Andalus to Córdoba in 1162 (which had dire consequences for Seville, reportedly depopulated and under starvation),[33] Seville became the definitive seat of the Andalusi part of the Almohad Empire in 1163,[34][35] a twin capital alongside Marrakesh. Almohads carried out a large urban renewal.[36] By the end of the 12th century, the walled enclosure perhaps contained 80,000 inhabitants.[37]

In the wider context of the Castilian–Leonese conquest of the Guadalquivir Valley that ensued in the 13th century, Ferdinand III laid siege on Seville in 1247. A naval blockade came to prevent relief of the city.[38] The city surrendered on 23 November 1248,[39] after fifteen months of siege. The conditions of capitulation contemplated the eviction of the population, with contemporary sources seemingly confirming that a mass movement of people out of Seville indeed took place.[40]

The city's development continued after the Castilian conquest in 1248. Public buildings were constructed including churches—many of which were built in the Mudéjar and Gothic styles—such as the Seville Cathedral, built during the 15th century with Gothic architecture.[41] Other Moorish buildings were converted into Catholic edifices, as was customary of the Catholic Church during the Reconquista. The Moors' Palace became the Castilian royal residence, and during Pedro I's rule it was replaced by the Alcázar (the upper levels are still used by the Spanish royal family as the official Seville residence).

After the 1391 pogrom, believed to having been instigated by the Archdeacon Ferrant Martínez, all the synagogues in Seville were converted to churches (renamed Santa María la Blanca, San Bartolomé, Santa Cruz, and Convento Madre de Dios). The Jewish quarter's land and shops (which were located in modern-day Santa Cruz neighbourhood) were appropriated by the church. Many Jews were killed during the pogrom, although most were forced to convert.

The first tribunal of the Spanish Inquisition was instituted in Seville in 1478. Its primary charge was to ensure that all nominal Christians were really behaving like Christians, and not practicing what Judaism they could in secret. At first, the activity of the Inquisition was limited to the dioceses of Seville and Córdoba, where the Dominican friar, Alonso de Ojeda, had detected converso activity.[42] The first Auto de Fé took place in Seville on 6 February 1481, when six people were burned alive. Alonso de Ojeda himself gave the sermon. The Inquisition then grew rapidly. The Plaza de San Francisco was the site of the 'autos de fé'. By 1492, tribunals existed in eight Castilian cities: Ávila, Córdoba, Jaén, Medina del Campo, Segovia, Sigüenza, Toledo, and Valladolid;[43] and by the Alhambra Decree all Jews were forced to convert to Catholicism or be exiled (expelled) from Spain.[44]

Early modern period

Following the Columbian exploration of the New World, Seville was chosen as headquarters of the Casa de Contratación in 1503, which was the decisive development for Seville becoming the port and gateway to the Indies.[45] Unlike other harbours, reaching the port of Seville required sailing about 80 kilometres (50 mi) up the River Guadalquivir. The choice of Seville was made in spite of the difficulties for navigation in the Guadalquivir stemming from the increasing tonnage of ships as a result of the relentless drive to make maritime transport cheaper during the late Middle Ages.[46] Nevertheless, technical suitability issues notwithstanding, the choice was still reasonable in the sense that Seville had become the largest demographic, economic and financial centre of Christian Andalusia in the late Middle Ages.[47]

A 'golden age of development' commenced in Seville, due to its being the only port awarded the royal monopoly for trade with the growing Spanish colonies in the Americas and the influx of riches from them.

Since only sailing ships leaving from and returning to the inland port of Seville could engage in trade with the Spanish Americas, merchants from Europe and other trade centres needed to go to Seville to acquire New World trade goods. The city's population grew to more than a hundred thousand people.[48]

In the late 16th century the monopoly was broken, with the port of Cádiz also authorised as a port of trade. Throughout the 17th century, colonial trade declined. Spain's American Colonies improved their production of basic goods, reducing their need to import. Compounded with these tribulations was the silting of the Guadalquivir river in the 1620s, which made Seville's harbors harder to use, and ceased upriver shipping.[49][50] The Great Plague of Seville in 1649, exacerbated by excessive flooding of the Guadalquivir, reduced the population by almost half, and it would not recover until the early 19th century.[51][52] By the 18th century, Seville's international importance was in decline. After the silting up of the harbour by the River Guadalquivir, upriver shipping ceased and the city went into relative economic decline.

The writer Miguel de Cervantes lived primarily in Seville between 1596 and 1600. Because of financial problems, Cervantes worked as a purveyor for the Spanish Armada, and later as a tax collector. In 1597, discrepancies in his accounts of the three years previous landed him in the Royal Prison of Seville for a short time. His short story Rinconete y Cortadillo, since the 19th century one of his most-read pieces, includes much description of Sevillian society; it features two young vagabonds who come to Seville, attracted by the riches and disorder that the 16th-century commerce with the Americas had brought to the city.

During the 18th century Charles III of Spain promoted Seville's industries. Construction of the Real Fábrica de Tabacos (Royal Tobacco Factory) began in 1728. It was the second-largest building in Spain, after the royal residence El Escorial. Since the 1950s it has been the seat of the rectorate (administration) of the University of Seville, as well as its Schools of Law, Philology (language/letters), Geography, and History.[53]

More operas have been set in Seville than in any other city of Europe. In 2012, a study of experts concluded the total number of operas set in Seville is 153. Among the composers who fell in love with the city are Beethoven (Fidelio), Mozart (The Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni), Rossini (The Barber of Seville), Donizetti (La favorite), and Bizet (Carmen).[54]

The first newspaper in Spain outside of Madrid was Seville's Hebdomario útil de Seville, which began publication in 1758.

Late modern history

Between 1825 and 1833, Melchor Cano acted as chief architect in Seville; most of the urban planning policy and architectural modifications of the city were made by him and his collaborator Jose Manuel Arjona y Cuba.[55]

Industrial architecture surviving today from the first half of the 19th century includes the ceramics factory installed in the Carthusian monastery at La Cartuja in 1841 by the Pickman family, and now home to the El Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo (CAAC),[56] which manages the collections of the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Sevilla.[57] It also houses the rectory of the UNIA.[58]

In the years that Queen Isabel II ruled directly, about 1843–1868, the Sevillian bourgeoisie invested in a construction boom unmatched in the city's history. The Isabel II bridge, better known as the Triana bridge, dates from this period; street lighting was expanded in the municipality and most of the streets were paved during this time as well.[59]

By the second half of the 19th century, Seville had begun an expansion supported by railway construction and the demolition of part of its ancient walls, allowing the urban space of the city to grow eastward and southward. The Sevillana de Electricidad Company was created in 1894 to provide electric power throughout the municipality,[60] and in 1901 the Plaza de Armas railway station was inaugurated.

The Museum of Fine Arts (Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla) opened in 1904.

In 1929 the city hosted the Ibero-American Exposition, which accelerated the southern expansion of the city and created new public spaces such as the Parque de María Luisa (Maria Luisa Park) and the adjoining Plaza de España. Not long before the opening, the Spanish government began a modernisation of the city in order to prepare for the expected crowds by erecting new hotels and widening the mediaeval streets to allow for the movement of automobiles.[61]

Seville fell very quickly at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. General Queipo de Llano carried out a coup within the city, quickly capturing the city centre.[62] Radio Seville opposed the uprising and called for the peasants to come to the city for arms, while workers' groups established barricades.[62] Queipo then moved to capture Radio Seville, which he used to broadcast propaganda on behalf of the Francoist forces.[62] After the initial takeover of the city, resistance continued among residents of the working-class neighbourhoods for some time, until a series of fierce reprisals took place.[63]

Under Francisco Franco's rule Spain was officially neutral in World War II (although it did collaborate with the Axis powers),[64][65][66] and like the rest of the country, Seville remained largely economically and culturally isolated from the outside world. In 1953 the shipyard of Seville was opened, eventually employing more than 2,000 workers in the 1970s. Before the existence of wetlands regulation in the Guadalquivir basin, Seville suffered regular heavy flooding; perhaps worst of all were the floods that occurred in November 1961 when the River Tamarguillo, a tributary of the Guadalquivir, overflowed as a result of a prodigious downpour of rain, and Seville was consequently declared a disaster zone.[67]

Trade unionism in Seville began during the 1960s with the underground organisational activities of the Workers' Commissions or Comisiones Obreras (CCOO), in factories such as Hytasa, the Astilleros shipyards, Hispano Aviación, etc. Several of the movement's leaders were imprisoned in November 1973.

Recent developments

On 3 April 1979 Spain held its first democratic municipal elections after the end of Franco's dictatorship; councillors representing four different political parties were elected in Seville. On 5 November 1982, Pope John Paul II arrived in Seville to officiate at a Mass before more than half a million people at the fairgrounds. He visited the city again on 13 June 1993, for the International Eucharistic Congress.

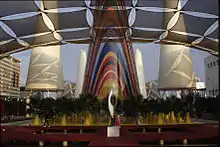

In 1992, coinciding with the fifth centenary of the Discovery of the Americas, the Universal Exposition was held for six months in Seville, on the occasion of which the local communications network and urban infrastructure was greatly improved under a 1987 PGOU plan launched by Mayor Manuel del Valle:[68] the SE-30 ring road around the city was completed and new highways were constructed; the new Seville-Santa Justa railway station had opened in 1991, while the Spanish High-Speed Rail system, the Alta Velocidad Española (AVE), began to operate between Madrid-Seville. The Seville Airport was expanded with a new terminal building designed by the architect Rafael Moneo, and various other improvements were made. The Alamillo Bridge and the Centenario Bridge, both crossing over the Guadalquivir, also were built for the occasion. Some of the installations remaining at the site after the exposition were converted into the Scientific and Technological Park Cartuja 93.

In 2004 the Metropol Parasol project, commonly known as Las Setas ('The Mushrooms'), due to the appearance of the structure, was launched to revitalise the Plaza de la Encarnación, for years used as a car park and seen as a dead spot between more popular tourist destinations in the city. The Metropol Parasol was completed in March 2011,[69] costing just over €102 million in total, more than twice as much as originally planned.[70] Constructed from crossed wooden beams, Las Setas is said to be the largest timber-framed structure in the world.[71]

Geography and climate

Location

_Seville%252C_Spain_(49104522676)_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Seville has an area of 141 km2 (54 sq mi), according to the National Topographic Map (Mapa Topográfico Nacional) series from the Instituto Geográfico Nacional – Centro Nacional de Información Geográfica, the country's civilian survey organisation (pages 984, 985 and 1002). The city is situated in the fertile valley of the River Guadalquivir. The average height above sea level is 7 metres (23 feet). Most of the city is on the east side of the river, while Triana, La Cartuja and Los Remedios are on the west side. The Aljarafe region lies further west, and is considered part of the metropolitan area. The city has boundaries on the north with La Rinconada, La Algaba and Santiponce; on the east with Alcalá de Guadaira; on the south with Dos Hermanas and Gelves and on the west with San Juan de Aznalfarache, Tomares and Camas.

Seville is on the same parallel as United States west coast city San Jose in central California. São Miguel, the main island of the Azores archipelago, lies on the same latitude. Further east from Seville in the Mediterranean Basin, it is on the same latitude as Catania in Sicily, Italy and just south of Athens, the capital of Greece. Beyond that, it is located on the same parallel as South Korean capital, Seoul. Seville is located inland, not very far from the Andalusian coast, but still sees a much more continental climate than the nearest port cities, Cádiz and Huelva. Its distance from the sea makes summers in Sevilla much hotter than along the coastline.

Climate

Seville has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa), featuring very hot, dry summers and mild winters with moderate rainfall.[72] Seville has an annual average of 19.2 °C (67 °F). The annual average temperature is 25.4 °C (78 °F) during the day and 13.0 °C (55 °F) at night.[73] Seville is located in the lower part of the Guadalquivir Valley, which is often referred to as "the frying pan of Andalucia", as it features the hottest cities in the country.[74][75][76]

Seville is the warmest city in Continental Europe.[77] It is also the hottest major metropolitan area in Europe, with summer average high temperatures of above 35 °C (95 °F)[78] and also the hottest in Spain.[79] After the city of Córdoba (also in Andalusia), Seville has the hottest summer in Europe among all cities with a population over 100,000 people, with average daily highs of 36.0 °C (97 °F) in July.[80] On average, Seville has around 60 days a year with maximum temperatures over 35.0 °C (95.0 °F).[81]

Temperatures above 40 °C (104 °F) are not uncommon in summer and it became the first city in the world to name a heat wave, which they nicknamed "Zoe".[82] The hottest temperature extreme of 46.6 °C (116 °F) was registered by the weather station at Seville Airport on 23 July 1995 while the coldest temperature extreme of −5.5 °C (22 °F) was also registered by the airport weather station on 12 February 1956.[83] A historical record high (disputed) of 50.0 °C (122 °F) was recorded on 4 August 1881, according to the NOAA Satellite and Information Service.[84] There is an unaccredited record by the National Institute of Meteorology of 47.2 °C (117 °F) on 1 August during the 2003 heat wave, according to a weather station (83910 LEZL) located in the southern part of Seville Airport, near the former US San Pablo Air Force Base. This temperature would be one of the highest ever recorded in Spain, yet it hasn't been officially confirmed.[85]

The average sunshine hours in Seville are approximately 3000 per year. Snowfall is virtually unknown, and the last important snowfall occurred in 1954. Since the year 1500, only 10 snowfalls have been recorded/reported in Seville. During the 20th century, Seville registered just 2 snowfalls, the last one on 2 February 1954.[86][87]

- Winters are mild: December and January are the coolest months, with average maximum temperatures around 16 to 17 °C (61 to 63 °F) and minimums of 6 to 7 °C (43 to 45 °F).

- Summers are very hot: July and August are the hottest months, with average maximum temperatures around 35 to 36 °C (95 to 97 °F) and minimums of 20 to 21 °C (68 to 70 °F).

- Precipitation varies from 500 to 600 mm (19.7 to 23.6 in) and there are around 50 rainy days per year, with frequent torrential rain. December is the wettest month, with an average rainfall of 99 millimetres (3.9 in).

| Climate data for Seville Airport (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 16.2 (61.2) |

18.2 (64.8) |

21.5 (70.7) |

23.7 (74.7) |

27.8 (82.0) |

32.4 (90.3) |

35.7 (96.3) |

35.6 (96.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

26.0 (78.8) |

20.1 (68.2) |

16.8 (62.2) |

25.4 (77.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.2 (52.2) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.3 (70.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.1 (82.6) |

24.7 (76.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

19.3 (66.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.7 (58.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.7 (58.5) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.4 (45.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 56.3 (2.22) |

46.2 (1.82) |

46.9 (1.85) |

54.0 (2.13) |

33.9 (1.33) |

5.8 (0.23) |

0.6 (0.02) |

2.5 (0.10) |

33.1 (1.30) |

75.4 (2.97) |

72.2 (2.84) |

77.2 (3.04) |

504.1 (19.85) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 5.9 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 4.2 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 50.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.8 | 67.8 | 62.0 | 57.8 | 51.1 | 45.5 | 42.4 | 45.6 | 54.1 | 63.5 | 71.5 | 76.5 | 59.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 202.0 | 212.2 | 246.3 | 270.2 | 324.9 | 357.3 | 388.1 | 364.3 | 278.4 | 244.4 | 205.3 | 185.9 | 3,279.3 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization Normals (NOAA) [88] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Seville Airport (1981–2010), extremes (1941–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 24.2 (75.6) |

28.0 (82.4) |

32.9 (91.2) |

36.9 (98.4) |

41.0 (105.8) |

45.2 (113.4) |

46.6 (115.9) |

45.9 (114.6) |

44.8 (112.6) |

37.4 (99.3) |

31.2 (88.2) |

24.5 (76.1) |

46.6 (115.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 16.2 (61.2) |

18.1 (64.6) |

21.9 (71.4) |

23.4 (74.1) |

27.2 (81.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.5 (95.9) |

31.7 (89.1) |

26.0 (78.8) |

20.2 (68.4) |

16.6 (61.9) |

25.4 (77.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.0 (51.8) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.3 (63.1) |

20.7 (69.3) |

25.1 (77.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

27.9 (82.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

20.2 (68.4) |

15.1 (59.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

19.2 (66.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.7 (42.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

11.1 (52.0) |

14.2 (57.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.3 (68.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.3 (45.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4.4 (24.1) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

1.0 (33.8) |

3.8 (38.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.4 (52.5) |

12.0 (53.6) |

8.6 (47.5) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 66 (2.6) |

50 (2.0) |

36 (1.4) |

54 (2.1) |

31 (1.2) |

10 (0.4) |

2 (0.1) |

5 (0.2) |

27 (1.1) |

68 (2.7) |

91 (3.6) |

99 (3.9) |

539 (21.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 6.1 | 5.8 | 4.3 | 6.1 | 3.7 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 7.5 | 50.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 67 | 59 | 57 | 53 | 48 | 44 | 48 | 54 | 62 | 70 | 74 | 59 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 183 | 189 | 220 | 238 | 293 | 317 | 354 | 328 | 244 | 217 | 181 | 154 | 2,918 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[89][90] | |||||||||||||

Government

Municipal government and administration

.jpg.webp)

Seville is a municipality, the basic level of local government in Spain. The Ayuntamiento is the body charged with the municipal government and administration. The Plenary of the ayuntamiento is formed by 31 elected municipal councillors, who in turn invest the mayor. The last municipal election took place on 26 May 2019. The current mayor is Antonio Muñoz (Spanish Socialist Workers' Party), who has held the post since the reign of the previous mayor, Juan Espadas in early 2022.

Regional and provincial capital

Seville is the capital of the autonomous community of Andalusia, according to Article 4 of the Statute of Autonomy of Andalusia of 2007, and is the capital of the Province of Seville as well. The historical building of the Palace of San Telmo is now the seat of the presidency of the Andalusian Autonomous Government. The administrative headquarters are in Torre Triana, in La Cartuja. The Hospital de las Cinco Llagas (literally, "Hospital of the Five Holy Wounds") is the current seat of the Parliament of Andalusia.

Districts and neighbourhoods

The municipal administration is decentralized into 11 districts, further divided into 108 neighbourhoods.

- Casco Antiguo

- Distrito Sur

- Triana

- Macarena

- Nervión

- Los Remedios

- Este-Alcosa-Torreblanca

- Cerro-Amate

- Bellavista-La Palmera

- San Pablo-Santa Justa

Main sights

Seville is a big tourist centre in Spain. In 2018, there were over 2.5 million travellers and tourists who stayed at a tourist accommodation, placing it third in Spain after Madrid and Barcelona. The city has an overall low level of seasonality, so there are tourists year-round.[91] There are many landmarks, museums, parks, gardens and other kinds of tourist spots around the city so there is something for everyone. The Alcázar, the Cathedral, and the General Archive of the Indies are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Many of the city's most important sights and monuments are located in the historic centre (Casco Antiguo). To the north of the centre is the Macarena neighbourhood, which contains some important monuments and religious buildings, such as the Museum and Catholic Church of La Macarena or the Hospital de las Cinco Llagas. Across the river, on the west bank of the Guadalquivir, the neighbourhood of Triana had an important role in the history of the city.

Churches

The Seville Cathedral, officially the Cathedral of Saint Mary of the See, is considered the largest Gothic cathedral in the world and one of the largest cathedrals in the world.[92][93][94] Incorporating parts of the city's former main mosque that was built under the Almohads in the 12th century, the current building is a massive Gothic structure begun after 1401 and finished in 1506, with additional reconstruction occurring between 1511 and 1519.[95] The church contains a number of important tombs, including one of the two claimed burial places of Christopher Columbus,[96] as well as many important artworks, including the largest retable (altarpiece) in Spain.[95] A number of later additions, mostly in Plateresque or Renaissance style, were added around the outside of the Gothic structure after its initial construction.[95]

One of the city's most prominent landmarks is the cathedral's bell tower, the Giralda, formerly the minaret of the Almohad mosque. The minaret's main shaft is a little over 50 meters tall. The tower was further heightened in the 16th century by the addition of a large Renaissance-style belfry, which brings its total height to around 95 or 96 meters.[97][98] The top of the tower is crowned by the Giraldillo, a cast bronze weather vane sculpture, from which the name "Giralda" is derived.[98]

The Church of San Salvador, located at Plaza de San Salvador, is the second largest church in the city after the cathedral. Originally converted from the city's oldest mosque, it was rebuilt in Baroque form in the 17th century and was the city's only collegiate church.[99] The Church of Saint Louis of France, built between 1699 and 1731 and designed by Leonardo de Figueroa, represents another example of Baroque architecture.[99][100]

Palaces and mansions

To the south of the cathedral, the Alcázar is a sprawling palace and garden complex which served as the city's center of power. The site was occupied since ancient times but was located outside the Roman city walls.[101] The current palace complex was founded in the 10th century as a governor's palace, then expanded in the 11th century when it became the palace of the Abbadid rulers. Some limited parts of the palace still date from its 12th-century expansion under Almohad rule, but most of the site was redeveloped after the Christian conquest of the city in the 13th century. A major construction campaign took place in the 1360s under Pedro I, who constructed a new palace in Mudéjar style, aided in part by craftsmen from Granada. Richly-decorated chambers and courtyards date from this period, such as the Patio de las Doncellas and the Salón de Embajadores.[101][102] Further additions took place under the Catholic Monarchs in Renaissance style, which continued under the Habsburgs. The extensive gardens were also redesigned in this style and then further developed in the 17th century.[95] The palace has been used as a filming location for various productions, including Game of Thrones.[103]

The Archbishop's Palace stands over the site of the former Roman baths of the city. The property was originally donated by Ferdinand III to Bishop Don Remondo in 1251, but the current building was built in the second half of the 16th century, followed by later additions. Its Baroque doorway was completed in 1704 by Lorenzo Fernándes de Iglesias.[104]

A number of other houses and wealthy mansions have been preserved across the city since the 16th century.[105] Among the most famous is the Casa de Pilatos ('House of Pilate'), an aristocratic mansion blending multiple architectural styles. The house, bought by the Enriquez de Ribera family in 1483,[106] has a typical courtyard plan but mixes older Isabelline and Mudéjar decoration with later Renaissance elements.[107] After Don Fadrique Enriquez de Ribera returned from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1520, he commissioned a stone portal at the entrance of the family mansion. The portal became the starting point for the Via Crucis to the Cruz del Campo, and later writers claimed it was modeled on the doorway of the house of Pontius Pilate in the Holy Land, thus earning the house its current name.[107][106]

Other historic mansions include the Palace of the Countess of Lebrija, the Palacio de las Dueñas, and the Casa de los Pinelos. The Casa del Rey Moro is considered the oldest in Seville, with its origins dated to the 15th century.[108]

Fortifications

The city walls of Seville were first built in ancient times on the orders of Julius Caesar.[109] After the Viking attack on the city in 844, the walls were rebuilt on the orders of Abd ar-Rahman II. They were expanded under the Almoravids in 1126 and in 1221 the Almohads added a moat and a second outer line of walls. Most of the walls were demolished after 1861 to reduce restrictions on urban development, but a significant portion of the northern walls can still be seen today.[109]

The Torre del Oro is an Almohad defensive tower dating to 1220–1221. The tower was integrated into the city's defensive system and protected the city's harbour, along with another tower across the river. Between the bases of the two towers a chain could be raised to block ships and prevent entry into the port.[110]

Civic buildings and other monuments

_-_2023-04-24_-_14.jpg.webp)

The City Hall (Ayuntamiento) was begun by architect Diego de Riaño, who worked on it between 1527 and 1534 and designed the eastern façade on Plaza de San Francisco, a highlight of the Plateresque style.[111][112] He was succeeded by other architects, including Hernan Ruiz II after 1560, who added a double-arched loggia on the western façade.[112] The Royal Prison originally stood nearby, where Cervantes was imprisoned and where it is believed he was inspired to write Don Quixote.[112] In 1840, the nearby Convent of San Francisco was demolished and replaced by the present-day Plaza Nueva in 1854. After this, the city hall's was partly remodeled by Demetrio de los Ríos and Balbino Marrón. It was given a new western façade in Neoclassical style, completed in 1867.[112][113]

The General Archive of the Indies (Archivo General de Indias), located between the Cathedral and the Alcázar, is the repository of valuable archival documents relating to the Spanish Empire in the Americas and the Philippines up to 1760.[114] The building itself was designed in a Spanish Renaissance style in 1572 by Juan de Herrera to house the merchants' guild. Construction began in the 1580s and was not finished until 1646. The building was converted into the new Archive of the Indies in 1785.[115]

.jpg.webp)

The Palacio de San Telmo was originally a naval college established in 1671. Between 1722 and 1735 the building was completed by Leonardo de Figueroa and his son Matías, who designed its present-day façade, one of the most important monuments of Baroque architecture in Andalusia.[100] The building now serves as the seat for the Andalusian Autonomous Government.[116]

The Royal Tobacco Factory (Real Fábrica de Tabacos), located near the Palacio de San Telmo, was built between 1728 and 1771. It was designed in a Baroque style by Sebastian van der Borcht.[100] It replaced an earlier tobacco factory built in 1687, which in turn had replaced Seville's first tobacco factory, San Pedro, which opened in a former women's penitentiary in 1620.[117] Upon completion, the new factory was the largest industrial building in the world and included its own chapel and its own prison, and operated under its own laws.[117]

The city's bullring, the Real Maestranza, was designed in 1761 by Vicente San Martin. Its Baroque façade was completed in 1787 but the rest of the building was only completed in 1881.[118] The venue can accommodate 14,000 spectators.[119]

The Metropol Parasol, in La Encarnación square, is the world's largest wooden structure.[120] A monumental umbrella-like building designed by the German architect Jürgen Mayer, finished in 2011. This modern architecture structure houses the central market and an underground archaeological complex. The terrace roof is a city viewpoint.[121]

Parque de María Luisa

The sprawling Parque de María Luisa (María Luisa Park) was designed by architect Aníbal González for the 1929 Ibero-American Exposition. The park includes two major plazas, the Plaza de España and the Plaza de América, and several monuments and museums. They include outstanding examples of regionalist Revival architecture, a mix of Neo-Mudéjar and Neo-Renaissance, lavishly ornamented with typical glazed tiles.[122][123]

At the park's north end, the semi-circular Plaza de España is marked by tall towers and a series of benches covered in painted tiles dedicated to each of the 48 provinces of Spain.[122] The location has been used in the filming of several movies.[124]

At the southern end of the park, the Plaza de América is flanked by three structures emulating different historical styles: the Royal Pavilion has Gothic features, the Mudéjar Pavilion has a Mudéjar style, and the Bellas Artes Pavilion has a Renaissance style. The two latter pavilions are each used as museums today.[125][122]

Museums

The most important art collection of Seville is the Museum of Fine Arts of Seville. It was established in 1835 in the former Convent of La Merced. It holds many masterworks by Murillo, Pacheco, Zurbarán, Valdés Leal, and others masters of the Baroque Sevillian School, containing also Flemish paintings of the 15th and 16th centuries.

Other museums in Seville are:

- The Archeological Museum of Seville, which contains collections from the Tartessian, Roman, Almohad, and Christian periods. It is located at Plaza América in Parque de María Luisa.

- The Museum of Arts and Popular Customs of Seville, also in Plaza América, across from the Archaeological Museum.

- The Andalusian Contemporary Art Centre, situated in the neighbourhood of La Cartuja.

- The Naval Museum, housed in the Torre del Oro, next to the River Guadalquivir.

- The Carriages Museum, in the Los Remedios neighbourhood.

- The Flamenco Art Museum

- The Bullfighting Museum, in the Maestranza bullring.

- The Palace of the Countess of Lebrija, a private collection that contains many of the mosaic floors discovered in the nearby Roman town of Italica.

- The Centro Velázquez (Velázquez Centre) located at the Old Priests Hospital in the touristic Santa Cruz neighbourhood.

- The Antiquarium in Metropol Parasol, an underground museum which is composed of the most important archaeological site of the ancient Roman stage of Seville and remains preserved.

- The Castillo de San Jorge (Castle of St. George) is situated near the Triana market, next to the Isabel II bridge. It was the last seat for the Spanish Inquisition.

- The Museum and Treasure of La Macarena, where the collection of the Macarena brotherhood is exhibited. This exhibition gives visitors an accurate impression of Seville's Holy Week.

- La Casa de la Ciencia (The House of Science), a science centre and museum opposite the María Luisa Park.

- Museum of Pottery in Triana.

- Pabellon de la Navegación (Pavilion of Navigation).

Other parks and gardens

In addition to the large Parque de María Luisa, the city contains other parks and gardens, including:

- The Alcázar Gardens, within the grounds of the Alcázar palace, consist of several sectors developed in different historical styles.

- The Gardens of Murillo and the Gardens of Catalina de Ribera, both along and outside the south wall of the Alcázar, lie next to the Santa Cruz quarter.

- The Parque del Alamillo y San Jerónimo, the largest park in Andalusia, was originally built for Seville Expo '92 to reproduce the Andalusian native flora. It lines both Guadalquivir shores around the San Jerónimo meander. The 32-metres-high bronze sculpture, The Birth of a New Man (popularly known as Columbus's Egg, el Huevo de Colón), by the Georgian sculptor Zurab Tsereteli,[126] is located in its northwestern sector.

- The American Garden, also completed for Expo '92, is in La Cartuja. It is a public botanical garden, with a representative collection of American plants donated by different countries on the occasion of the world exposition. Despite its extraordinary botanical value, it remains a mostly abandoned place.

- The Buhaira Gardens, also historically known as the Huerta del Rey, are a public park and historic site, originally created as a garden estate during the Almohad period (12th century).[127][128]: 211

Culture

Theaters

The Teatro Lope de Vega is located on Avenida de María Luisa avenue (next to Parque de María Luisa). It was built in 1929, being its architect Vicente Traver y Tomás. It was the auditorium of the pavilion of the city in the Ibero-American Exhibition. This pavilion had a large room that became the Casino of the Exhibition. The theater occupied an area of 4600 m2 and could accommodate 1100 viewers. Its architecture is Spanish Baroque Revival, being the building faithful to this style both in the set and in its ornamentation.

It has hosted varied performances, including theater, dance, opera, jazz, and flamenco and nowadays the most outstanding of the panorama is its programming national and international, becoming one of the most important theaters in Spain.[129]

Other important theatres are Teatro de la Maestranza, Auditorio Rocío Jurado and Teatro Central.

Seville also has a corral de comedias theatre, which is the Corral del Coliseo, now used as a residential building.

Festivals

There are many entertainment options around the city of Seville and one of its biggest attractions is the numerous festivals that happen around the year. Some of the festivals concentrate on religion and culture, others focus on the folklore of the area, traditions, and entertainment.[130]

Holy Week in Seville

Semana Santa is celebrated all over Spain and Latin America, but the celebration in Seville is large and well known as a Fiesta of International Tourist Interest. 54 local brotherhoods,[131] or "cofradías", organize floats and processions throughout the week, reenacting the story of the Passion of Christ. There is traditional music and art incorporated into the processions, making Semana Santa an important source of both material and immaterial Sevillian cultural identity.[132][133][134]

Bienal de Flamenco

Seville is home to the bi-annual flamenco festival La Bienal, which claims to be "the biggest flamenco event worldwide" and lasts for nearly a month.[135]

Velá de Santiago y Santa Ana

In the district of Triana, the Velá de Santiago y Santa Ana is held every July and includes sporting events, performances, and cultural activities as the city honors St. James and St. Ana.[136]

Feria de Abril

The April Fair (Feria de Abril) is a huge celebration that takes place in Seville about two weeks after the Holy Week. It was previously associated with celebrating livestock; however, nowadays its purpose is to create a fun cheerful environment tied to the appreciation of the Spanish folklore.[137]

During the Feria, families, businesses, and organisations set up casetas (marquees) in which they spend the week dancing, drinking, and socialising. Traditionally, women wear elaborate flamenco dresses and men dress in their best suits. The marquees are set up on a permanent fairground in the district of Los Remedios,[138] in which each street is named after a famous bullfighter.

Salón Náutico Internacional de Sevilla

The International Boat Show of Seville is an annual event that takes place in the only inland maritime port of the country, which is one of the most important in Europe.[139]

Music

Seville had a vibrant rock music scene in the 1970s and 1980s[141] with bands like Triana, Alameda and Smash, who fused Andalusia's traditional flamenco music with British-style progressive rock. The punk rock group Reincidentes and indie band Sr Chinarro, as well as singer Kiko Veneno, rose to prominence in the early 1990s. The city's music scene now features rap acts such as SFDK, Mala Rodríguez, Dareysteel, Tote King, Dogma Crew, Bisley DeMarra, Haze and Jesuly. Seville's diverse music scene is reflected in the variety of its club-centred nightlife.

The city is also home to many theatres and performance spaces where classical music is performed, including Teatro Lope de Vega, Teatro La Maestranza, Teatro Central, the Real Alcazar Gardens and the Sala Joaquín Turina.

Despite its name, the sevillana dance, commonly presented as flamenco, is not thought to be of Sevillan origin. However, the folksongs called sevillanas are authentically Sevillan, as is the four-part dance performed with them.

On 19 November 2023, Seville will host the 24th Annual Latin Grammy Awards at the FIBES Conference and Exhibition Centre, making Seville the first city outside of the United States to host the Latin Grammy Awards.[142][143]

Flamenco

The Triana district in Seville is considered a birthplace of flamenco, where it found its beginning as an expression of the poor and marginalized. Seville's Gypsy population, known as Flamencos, were instrumental in the development of the art form. While it began as and remains a representation of Andalusian culture, it has also become a national heritage symbol of Spain.[144][145][146][147] There are more flamenco artists in Seville than anywhere else in the country, supporting an entire industry surrounding it and drawing in a significant amount of tourism for the city.[148]

Gastronomy

The tapas scene is one of the main cultural attractions of the city: people go from one bar to another, enjoying small dishes called tapas (literally "lids" or "covers" in Spanish, referring to their probable origin as snacks served on small plates used to cover drinks). Local specialities include fried and grilled seafood (including squid, choco (cuttlefish), swordfish, marinated dogfish, and ortiguillas), grilled and stewed meat, spinach with chickpeas, Jamón ibérico, lamb kidneys in sherry sauce, snails, caldo de puchero, and gazpacho. A sandwich known as a serranito is the typical and popular version of fast food.

Typical desserts from Seville include pestiños, a honey-coated sweet fritter; torrijas, fried slices of bread with honey; roscos fritos, deep-fried sugar-coated ring doughnuts; magdalenas or fairy cakes; yemas de San Leandro, which provide the city's convents with a source of revenue; and tortas de aceite, a thin sugar-coated cake made with olive oil. Polvorones and mantecados are traditional Christmas products, whereas pestiños and torrijas are typically consumed during the Holy Week.

Bitter Seville oranges grow on trees lining the city streets. Large quantities are collected and exported to Britain to be used in marmalade.[149] Locally, the fruit is used predominantly in aromatherapy, herbal medicine, and dietary diet products, rather than as a foodstuff.[150] According to legend, the Arabs brought the bitter orange to Seville from East Asia via Iraq around the 10th century to beautify and perfume their patios and gardens, as well as to provide shade.[151] The flowers of the tree are a source of neroli oil, commonly used in perfumery and in skin lotions for massage.

In 2021, the municipal water company, Emasesa, began a pilot scheme to use the methane produced as the fruit ferments to generate clean electricity. The company plans to use 35 tonnes of fruit to generate clean energy to power one of the city's water purification plants.[152]

Economy

Seville is the most populated city in southern Spain, and has the largest GDP (gross domestic product) of any in Andalusia,[153] accounting for one-quarter of its total GDP.[153] All municipalities in the metropolitan area depend directly or indirectly on Seville's economy, while agriculture dominates the economy of the smaller villages, with some industrial activity localised in industrial parks. The Diputación de Sevilla (Deputation of Seville), with provincial headquarters in the Antiguo Cuartel de Caballería (Old Cavalry Barracks) on Avenida Menendez Pelayo, provides public services to distant villages that they can not provide themselves.[154]

The economic activity of Seville cannot be detached from the geographical and urban context of the city; the capital of Andalusia is the centre of a growing metropolitan area. Aside from traditional neighbourhoods such as Santa Cruz, Triana and others, those further away from the centre, such as Nervión, Sevilla Este, and El Porvenir have seen recent economic growth. Until the economic crisis of 2007, this urban area saw significant population growth and the development of new industrial and commercial parks.[155]

During this period, availability of infrastructure in the city contributed to the growth of an economy dominated by the service sector,[156] but in which industry still holds a considerable place.[157]

Infrastructure

.jpg.webp)

The 1990s saw massive growth in investment in infrastructure in Seville, largely due to its hosting of the Universal Exposition of Seville in 1992. This economic development of the city and its urban area is supported by good transportation links to other Spanish cities, including a high-speed AVE railway connection to Madrid, and a new international airport.

Seville has the only inland port in Spain, located 80 km (50 mi) from the mouth of the River Guadalquivir. This harbour complex offers access to the Atlantic and the Mediterranean and allows trade in goods between the south of Spain (Andalusia, Extremadura) and Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. The port has undergone reorganisation. Annual tonnage rose to 5.3 million tonnes of goods in 2006.[158]

Cartuja 93 is a research and development park,[159] employing 15,000 persons. The Parque Tecnológico y Aeronáutico Aerópolis (Technological and Aeronautical Park)[160] is focused on the aircraft industry. Outside of Seville are nine PS20 solar power towers which use the city's sunny weather to provide most of it with clean and renewable energy.

The Sevilla Tower skyscraper was started in March 2008 and was completed in 2015. With a height of 180.5 metres (592 feet) and 40 floors, it is the tallest building in Andalusia.

Seville has conference facilities, including the Conference and Convention Centre.

Research and development

The Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas en Sevilla (CSIC) is based in the former Pavilion of Peru in the Maria Luisa Park. In April 2008 the city council of Seville provided a grant to renovate the building to create the Casa de la Ciencia (Science Centre) to encourage popular interest in science.[161] The internationally recognised company Neocodex has its headquarters in Seville; it maintains the first and largest DNA bank in Spain and has made significant contributions to scientific research in genetics.[162] Seville is also considered an important technological and research centre for renewable energy and the aeronautics industry.[163][164]

The output of the research centres in Sevillan universities working in tandem with city government, and the numerous local technology companies, have made Seville a leader among Spanish cities in technological research and development. The Parque Científico Tecnológico Cartuja 93 is a nexus of private and public investment in various fields of research.[165]

Principal fields of innovation and research are telecommunications, new technologies, biotechnology (with applications in local agricultural practices), environment and renewable energy.

Transport

Bus

Seville is served by the TUSSAM (Transportes Urbanos de Sevilla) bus network which runs buses throughout the city. The Consorcio de Transportes de Sevilla communicates by bus with all the satellite towns of Seville.

Two bus stations serve transportation between surrounding areas and other cities: Plaza de Armas Station, with destinations north and west, and Prado de San Sebastián Station, covering routes to the south and east. Plaza de Armas station has direct bus lines to many Spanish cities as well as Lisbon, Portugal.

Metro

The Seville Metro ("Metro de Sevilla" in Spanish) is a light metro network serving the city of Seville and its metropolitan area. The system is totally independent of any other rail or street traffic. All stations were built with platform screen doors.

It was the sixth Metro system to be built in Spain, after those in Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Bilbao and Palma de Mallorca. Currently, it is the fifth-biggest Metro company in Spain by the number of passengers carried (more than 12,000,000 in 2009).[166]

The metro of Sevilla has 1 line with 22 stations and is currently expanding, with 3 more different lines projected.

Tram

MetroCentro is a surface tramway serving the centre of the city. It began operating in October 2007.

The service has just five stops: Plaza Nueva, Archivo de Indias, Puerta de Jerez, Prado de San Sebastián and San Bernardo, all as part of Phase I of the project. It is expected to be extended to Santa Justa AVE station, including four new stops: San Francisco Javier, Eduardo Dato, Luis de Morales, and Santa Justa. This extension was postponed although the City Council had made expanding the metro lines a priority.

Train

The Seville-Santa Justa railway station is served by the AVE high-speed rail system, operated by the Spanish state-owned rail company Renfe. A five-line commuter rail service (Cercanías) joins the city with the Metropolitan area. Seville is on the Red Ciudades AVE, a net created with Seville connected to 17 major cities of Spain with high-speed rail.

Although Seville is close to the Portuguese city of Faro, it is not possible to cross the border by train.[167]

Bicycle

The Sevici community bicycle program has integrated bicycles into the public transport network. Bicycles are available for hire around the city at low cost, and green curb-raised bicycle lanes can be seen on most major streets. The number of people using bicycles as a means of transport in Seville has increased substantially in recent years, multiplying tenfold from 2006 to 2011.[168] As of 2015, an estimated 9 percent of all mechanized trips in the city (and 5.6 percent of all trips including those on foot) are made by bicycle.[169]

The city council signed a contract with the multinational corporation JCDecaux, an outdoor advertising company. The public bicycle rental system is financed by a local advertising operator in return for the city signing over a 10-year licence to exploit citywide billboards. The overall scheme is called Cyclocity[170] by JCDecaux, but each city's system is branded under an individual name.

As of 2022, some companies in the e-bike community bicycle program industry such as Lime (transportation company) and Ridemovi started working in the city,[171] thanks to the new parking spots made by the City Council of Seville

Airport

.jpg.webp)

The San Pablo Airport is the main airport for Seville and is Andalusia's second busiest airport, after Málaga's, and first in cargo. The airport handled 7,544,357 passengers and just under 9,891 tonnes of cargo in 2019.[172] It has one terminal and one runway.

It is one of many bases for the Spanish low-cost carrier Vueling, and from November 2010 Ryanair based aircraft at the airport.[173] In addition, Ryanair opened its first aircraft maintenance facility in Spain at Seville Airport in 2019.[174]

This enabled low-cost direct flights to several Spanish cities, as well as to the neighbor country of Portugal with weekly flights to Porto[175] and to other European cities.

Port

Seville is the only commercial river port in Spain and the only inland city in the country where cruise ships can arrive in the historical centre. On 21 August 2012, the Muelle de las Delicias, controlled by the Port Authority of Seville, hosted the cruise ship Azamara Journey for two days, the largest ship ever to visit the town. This vessel belongs to the shipping company Royal Caribbean and can accommodate up to 700 passengers.[176]

Roads

Seville has one ring road, the SE-30, which connects with the dual carriageway of the south, the A-4, that directly communicates the city with Cádiz, Cordoba and Madrid. Also there is another dual carriageway, the A-92, linking the city with Osuna, Antequera, Granada, Guadix and Almeria. The A-49 links Seville with Huelva and the Algarve in the south of Portugal.

Public transportation statistics

The average amount of time people spend commuting with public transit in Sevilla, for example to and from work, on a weekday is 34 min. 7% of public transit riders, ride for more than two hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is eight minutes, while 15% of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 5.6 kilometres (3.5 mi), while 7% travel for over 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) in a single direction.[177]

Education

Seville is home to three public universities. The University of Seville (US), founded in 1505; as of 2019, it had 72,000 students.[178] The Pablo de Olavide University (UPO), founded in 1997, with 9,152 students in 2019;[179] and the International University of Andalusia (UNIA), founded in 1994.[180]

The US and the UPO are important centres of learning in Western Andalusia as they offer a wide range of academic courses; consequently, the city has a large number of students from Huelva and Cádiz.

Additionally, there is the School of Hispanic American Studies, founded in 1942, the Menéndez Pelayo International University, based in Santander, which operates branch campuses in Seville, and Loyola University Andalusia.[181]

- International primary and secondary schools

- Lycée Français de Séville (French school)

- Deutsche Schule Sevilla (German school)

- St. George's British School

Seville is also home to many international schools and colleges that cater to American students who come to study abroad.

Sport

Seville is the hometown of two rival association football teams: Real Betis Balompié and Sevilla Fútbol Club; both teams play in La Liga. Each team has won the league once: Betis in 1935 and Sevilla in 1946.[182] Only Sevilla have won European competitions, winning consecutive UEFA Cup finals in 2006 and 2007[183] and the UEFA Europa League in 2014,[184] 2015, 2016, 2020 and 2023. The Ramón Sánchez Pizjuán and Benito Villamarín, stadiums of Sevilla and Betis respectively, were venues for the 1982 FIFA World Cup.[185] Sevilla's stadium also hosted the 1986 European Cup final[186] and the multi-purpose stadium built in 1999 La Cartuja, was the venue for the 2003 UEFA Cup final.[187] Seville has an ACB League basketball club, the Real Betis Baloncesto.

Seville has hosted both indoor (1991) and outdoor (1999) World Championships in athletics, while housed the tennis Davis Cup final in 2004 and 2011. The city unsuccessfully bid for the 2004[188] and 2008 Summer Olympics,[189] for which the 60,000-seat Estadio de La Cartuja was designed to stage. Seville's River Guadalquivir is one of only three FISA approved international training centres for rowing and the only one in Spain; the 2002 World Rowing Championships and the 2013 European Rowing Championships were held there.

In fiction

- The picaresque novel Rinconete y Cortadillo by Miguel de Cervantes takes place in the city of Seville.

- The novel La Femme et le pantin (The Woman and the Puppet) (1898) by Pierre Louÿs, adapted for film several times, is set mainly in Seville.

- Seville is the setting for the legend of Don Juan (inspired by the real aristocrat Don Miguel de Mañara) on the Paseo Alcalde Marqués de Contadero.

- Seville is the primary setting of many operas, the best known of which are Bizet's Carmen (based on Mérimée's novella), Rossini's The Barber of Seville, Verdi's La forza del destino, Beethoven's Fidelio, Mozart's Don Giovanni and The Marriage of Figaro, and Prokofiev's Betrothal in a Monastery.

- Seville is the setting of the novel The Seville Communion by Arturo Pérez-Reverte.

- Seville is both the location and setting for much of the 1985 Doctor Who television serial "The Two Doctors".

- Seville is also used as one of the locations in Dan Brown's Digital Fortress.

- Seville is one of the settings in Jostein Gaarder's book The Orange Girl (Appelsinpiken).

- Seville is the hometown of the two main characters in the 2000 film The Road to El Dorado by DreamWorks. Miguel and Tulio are con artists that stow away on a ship bound for the New World and win a map for the fabled lost city of gold, El Dorado, and are invariably seen as gods by the locals.

- Arthur Koestler's book Spanish Testament is based on the writer's experiences while held in the Seville prison, under a sentence of death, during the Spanish Civil War.

- Robert Wilson's police novel The Hidden Assassins (2006) concerns a terrorist incident in Seville and the political context thereof, with much local colour.

- The Plaza de España in the Parque de María Luisa appears in George Lucas' Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones, in The Dictator, starring Sacha Baron Cohen, as the palace of the dictator Aladeen, and in Lawrence of Arabia as the British Army headquarters in Cairo, while the courtyard was the King Alfonso XIII Hotel.

- The Plaza of the Americas also appeared in Lawrence, substituting for Jerusalem, and in Anthony Mann's El Cid. It also appears as the Palace of Vladek Sheybal's Bashaw in The Wind and the Lion (1975).

- The Alcázar and other sites appear in the television series Game of Thrones, in the cities of Dorne.

- In the 2016 film Assassin's Creed, Master Assassins Aguilar de Nerha and Maria escape execution and are pursued by Templars through the city, eventually performing Leaps of Faith off of an unfinished Seville Cathedral to escape.

- In Mission: Impossible 2, Ethan Hunt is sent to Seville to recruit Nyah Nordoff-Hall.

In travel writing

- The Tomb in Seville by Norman Lewis.

Twin towns – sister cities

Seville is twinned with the following cities:

Angers (France), 1989.[190]

Angers (France), 1989.[190] Barcelona (Spain), 1987.[190][191]

Barcelona (Spain), 1987.[190][191] Buenos Aires (Argentina), 1976.[190][192]

Buenos Aires (Argentina), 1976.[190][192] Columbus, Ohio (United States), 1988.[190][193]

Columbus, Ohio (United States), 1988.[190][193] Córdoba (Spain), 1908.[190]

Córdoba (Spain), 1908.[190] Guadalajara (Mexico), 1984.[190]

Guadalajara (Mexico), 1984.[190] Havana (Cuba), 2007.[190][192][194][195]

Havana (Cuba), 2007.[190][192][194][195] Kansas City, Missouri (United States), 1969. The relationship between Seville and Kansas City is due to a small replica of the Giralda tower, Sevilla's cathedral belltower, that exists in Kansas City.[196][197]

Kansas City, Missouri (United States), 1969. The relationship between Seville and Kansas City is due to a small replica of the Giralda tower, Sevilla's cathedral belltower, that exists in Kansas City.[196][197] Laredo (Spain), 2017.[198]

Laredo (Spain), 2017.[198] Marrakech (Morocco), 2017.[199]

Marrakech (Morocco), 2017.[199] Medina de Rioseco (Spain), 2016.[200]

Medina de Rioseco (Spain), 2016.[200] San Salvador (El Salvador), 2018.[201]

San Salvador (El Salvador), 2018.[201] Sevilla la Nueva (Spain).[190]

Sevilla la Nueva (Spain).[190]

- Partnerships

Titles

Seville has been given titles by Spanish monarchs and heads of state throughout its history.[203]

- Very Noble, by King Ferdinand III of Castile after his reconquest of the city.

- Very Loyal, by King Alfonso X of Castile for supporting him against a rebellion. See also the Motto "NO8DO".

- Very Heroic, by King Ferdinand VII of Spain by Royal Document on 13 October 1817 for support against the French invasion.

- Invictus (Invincible in Latin), by Queen Isabella II of Spain for the city's resistance against General Van Halen's asedium and bombing in 1843.

- Mariana, by General Francisco Franco in 1946 for the city's devotion to the Virgin Mary.

Notable people

- Maria Antonietta of Spain, Queen consort of Sardinia (1729–1785)

- Al-Mu'tamid ibn Abbad, poet and Arabic king of Sevilla 1040–1095

- Physician Avenzoar

- The family of the Arabic historian and sociologist Ibn Khaldun

- 13th-century poet Ibn Sahl of Seville

- Renaissance composers Cristóbal de Morales, Francisco Guerrero

- 16th-century novelist Mateo Alemán

- Playwrights Lope de Rueda and Hermanos Alvarez Quintero

- Historian of New Spain Bartolomé de Las Casas

- Colonial governor of La Florida and Cuba: Laureano de Torres y Ayala

- Colonial governor of La Florida: Pablo de Hita y Salazar

- Baroque painters Diego Velázquez, Valdés Leal and Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

- Educator Adelita Domingo

- Explorer and astronomer Antonio de Ulloa

- Renaissance poets Fernando de Herrera and Gutierre de Cetina

- Notable Costumbrista painter who liked to depict the 19th century society of Seville and its buildings José Jiménez Aranda

- Romantic poet Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer

- Bullfighters Juan Belmonte, Curro Romero, Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, Emilio Muñoz and José Gómez Ortega

- Second Spanish Republic Prime Minister Diego Martinez, communist politician José Díaz and Carlist politician Manuel Fal.

- 20th-century poets:

- Vicente Aleixandre (Nobel Laureate)

- Antonio and Manuel Machado

- Luis Cernuda

- Jose Julio Cabanillas Serrano continuing in the 21st–century

- Composer Joaquín Turina

- Cartoonist William Haselden

- Actors Juan Diego, Paco León

- Actresses Soledad Miranda, Verónica Sánchez, Carmen Sevilla, Paz Vega, Azucena Hernández

- Models

- Teresa Sánchez López who won the title of Miss National in the Miss Spain contest 1984 and, representing Spain, was close to the crown of Miss Universe in 1985 (1st runner up).

- Eva Maria González beauty queen and model who was Miss España 2003 (representing Andalusia)

- Singers Isabel Pantoja, Juanita Reina, Lole y Manuel, Paquita Rico, El Caracol, Falete, Pastora Soler, and Mala Rodríguez

- Comedian Manuel Summers

- Navy officer Miguel Buiza Fernández-Palacios who became Captain General of the Spanish Republican Navy

- Association footballers José Antonio Reyes, Fernando "Nando" Muñoz, Ricardo Serna, Sergio Ramos, Jesús Navas, Antonio Puerta, Carlos Marchena, Jesús Capitán "Capi", Adrián, Olga Carmona, Irene Guerrero

- Olympic swimmer Fátima Madrid

- Politicians Felipe González, President of the Government of Spain from 1982 to 1996, and Alfonso Guerra, vice-president from 1982 to 1991

- Maria Pages, dancer

- Jairo Barrull Fernández, Spanish Gypsy flamenco dancer

- El Risitas, humorist

- Criminal Manuel Delgado Villegas, serial killer

- Drag queen Carmen Farala, winner of the first season of Drag Race España

- Embroiderer Esperanza Elena Caro

- Mystic Bárbara de Santo Domingo

See also

- Cadillac Seville, a car that was named after the city

- Azulejo

- Isla Mágica

- Seville Public Library

- Seville Statement on Violence

- Church of Santa Maria la Blanca (Seville)

References

- ↑ Demographia: World Urban Areas, 2022

- ↑ "Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by metropolitan regions". ec.europa.eu.

- ↑ Staff (2020). "Seville, Spain". earth.esa.int. ESA Earth Online 2000 - 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ↑ Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History. Volume 4 (1200–1350). Brill. 2012. p. 9. ISBN 978-90-04-22854-2. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ↑ De Coripe a Sevilla por Utrera: formación y deformación de topónimos en el habla. Diputación de Sevilla. 2013. ISBN 978-84-940980-0-0. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ↑ SPAL: Revista de prehistoria y arqueología de la Universidad de Sevilla. Secretariado de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Sevilla. 1998. p. 93. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

La presencia de fenicios en la antigua Sevilla parece constatada por el topónimo Spal que en diversas lenguas semíticas significa "zona baja", "llanura verde" o "valle profundo"

- ↑ "La Emergencia de Sevilla". Universidad de Sevilla. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 José María de Mena (1992). Art and History of Seville. Casa Editrice Bonechi. p. 6. ISBN 978-88-7009-851-8.

- ↑ Echevarria, Ana (2008). Biografías mudéjares, o, La experiencia de ser minoría: biografías islámicas en la España cristiana. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. p. 394. ISBN 978-84-00-08744-9.

- ↑ Gerber, Jane S. (1992). The Jews of Spain. Simon and Schuster. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4391-0783-6.

- ↑ José María de Mena Plaza & Janés (1985). Historia de Sevilla. Plaza & Janés. p. 47. ISBN 978-84-01-37200-1.

- ↑ Calvert (2018). Southern Spain. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 17. ISBN 978-3-7340-3692-7.

- ↑ Manrique, Nelson (1993). Vinieron los Sarracenos...: el universo mental de la conquista de América. DESCO. p. 178. ISBN 978-84-89312-04-3.

- ↑ Glick, Thomas F. (2005). Islamic And Christian Spain in the Early Middle Ages. BRILL. p. 48. ISBN 90-04-14771-3.

- ↑ Glick, Thomas F. (1979). Islamic and Christian Spain in the Early Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. p. 323. ISBN 978-0-7837-0098-4.

- ↑ El Gharbi, Jalel (2009). "Thrène de Séville". Cahiers de la Méditerranée (in French) (79): 26–30. doi:10.4000/cdlm.4901.

- ↑ "Leyendas de Sevilla – 5 Hércules y la fundación de Sevilla". Aznalfarache.blogspot.com. 13 September 2010. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ Manuel Jesús Roldán Salgueiro (2007). Historia de Sevilla. Almuzara. ISBN 978-84-88586-24-7. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ José María de Mena (1985). Historia de Sevilla. Plaza & Janés. p. 39. ISBN 978-84-01-37200-1. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ "Proyecto Puntual de Investigación 1999: Intervención Puntual: "Estudios estratigráficos y análisis constructivos"". Real Alcázar (in Spanish). Real Alcázar de Sevilla. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

Los restos antrópicos más antiguos se situaban sobre esta terraza, bajo la muralla Septentrional del Alcázar, datados en el s. VII-VIII a.C.

- ↑ Elizabeth Nash (16 September 2005). Seville, Cordoba, and Granada: A Cultural History: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-19-972537-3.

- ↑ "Antiguas Murallas y Puertas de Sevilla". Degelo.com. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 González Athané, José (2012). "La influencia del río Guadalquivir en la imagen de la ciudad de Sevilla a lo largo de los siglos" (PDF). Paisajes modelados por el agua: entre el arte y la ingeniería. p. 102. ISBN 978-84-9852-345-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ↑ Calvo Capilla, Susana (2007). "Las primeras mezquitas de al-Andalus a través de las fuentes árabes (92/711 – 170/785)". Al-Qanṭara. Madrid: Ediciones CSIC. 28 (1): 167. doi:10.3989/alqantara.2007.v28.i1.34.

- ↑ Scheen, Rolf (1996). "Viking raids on the spanish peninsula". Militaria: Revista de Cultura Militar. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense (8): 67. ISSN 0214-8765.

- ↑ Valencia 1994, p. 136–137; 138.

- ↑ Valencia, Rafael (1994). "Islamic Seville: Its Political, Social and Cultural History". In Jayyusi, Salma Khadra (ed.). The Legacy of Muslim Spain (2nd ed.). Leiden, New York, Köln: EJ Brill. p. 138. ISBN 90-04-09599-3.

- ↑ García Sanjuán, Alejandro (2004). "Declive y extinción de la minoría cristiana en la Sevilla andalusí (ss. XI-XII)" (PDF). Historia. Instituciones. Documentos (31): 271–276. ISSN 0210-7716. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- 1 2 3 Valencia 1994, p. 139.

- ↑ Valor Piechotta, Magdalena; Lafuente Ibáñez, Pilar (2018). "La Sevilla 'abbādí" (PDF). In Sarr, Bilal (ed.). Tawa'if. Historia y Arqueología de los reinos taifas. Granada. p. 182. ISBN 978-84-949380-2-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ El Hour 1999, p. 289.

- ↑ Ramírez del Río, José (1999). "Pueblos de Sevilla en época islámica. Breve recorrido histórico-político" (PDF). Philologia Hispalensis. 13 (1): 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ↑ El Hour, Rachid (1999). "La transición entre las épocas almorávide y almohade vista a través de las familias de ulemas" (PDF). Estudios onomástico-biográficos de al-Andalus, IX. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. p. 291. ISBN 84-00-07860-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ↑ Domínguez Berenjeno, Enrique Luis (2001). "La remodelación urbana de Ishbilia a través de la historiografía almohade" (PDF). Actas de las II Jornadas Cordobesas de Arqueología Andaluza. Córdoba: UCOPress (12): 178–179. doi:10.21071/aac.v0i.11252 (inactive 1 August 2023).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - ↑ Buresi, Pascal (2017). "The story of the Almohads in the Kingdom of Fez and of Morocco". The Soul of Morocco. pp. 105–146.

- ↑ García-Sanjuan, Alejandro (2020). "Box 2.1 Seville". In Fierro, Maribel (ed.). The Routledge Handbook of Muslim Iberia. Routledge. pp. 23–25. ISBN 978-1-315-62595-9.

- ↑ Ladero Quesada, Miguel Ángel (1987). "Las ciudades de Andalucía occidental en la Baja Edad Media: sociedad, morfología y funciones urbanas". En la España medieval. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense. 10: 74. ISSN 0214-3038.

- ↑ Mott, Lawrence V. (2002). "Iberian Naval Power, 1000–1650" (PDF). In Hattendorf, John B.; Unger, Richard W. (eds.). War at Sea in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Boydell & Brewer. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-84615-171-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.