| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

The evolution of languages or history of language includes the evolution, divergence and development of languages throughout time, as reconstructed based on glottochronology, comparative linguistics, written records and other historical linguistics techniques. The origin of language is a hotly contested topic, with some languages tentatively traced back to the Paleolithic. However, archaeological and written records extend the history of language into ancient times and the Neolithic.

The distribution of languages has changed substantially over time. Major regional languages like Elamite, Sogdian, Koine Greek, or Nahuatl in ancient, post-classical and early modern times have been overtaken by others due to changing balance of power, conflict and migration. The relative status of languages has also changed, as with the decline in prominence of French and German relative to English in the late 20th century.

Prehistory

Paleolithic (200,000–20,000 BP)

The highly diverse Nilo-Saharan languages, first proposed as a family by Joseph Greenberg in 1963 might have originated in the Upper Paleolithic.[1] Given the presence of a tripartite number system in modern Nilo-Saharan languages, linguist N.A. Blench inferred a noun classifier in the proto-language, distributed based on water courses in the Sahara during the "wet period" of the Neolithic Subpluvial.[2]

Mesolithic (20,000–8,000 BP)

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, researchers attempted to reconstruct the Proto-Afroasiatic language, suggesting it likely arose between 18,000 and 12,000 years ago in the Levant, suggesting that it may have descended from the Natufian culture and migrated into Africa before diverging into different languages.[3][4]

Neolithic (12,000–6500 BP)

Population genetics research in the 2000s suggests that the very earliest predecessors of the Dravidian languages may have been spoken in south-west Iran between 15,000 and 10,000 years ago before spreading to India much later.[5] The Eastern Sudanic group of Nilo-Saharan languages may have unified around 7000 years ago.[1]

Aryon Rodrigues hypothesizes the emergence of a Proto-Tupian language between the Guaporé and Aripuanã rivers, in the Madeira River basin (corresponding to the modern Brazilian state of Rondônia) around 5000 years ago.[6]

Ancient history (3000 BCE–500 CE)

Africa

Beginning in the Levant around the 11th century BC, Phoenicia became an early trading state and colonizing power, spreading its language to what is now Libya, Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco as well as southern Spain, the Balearic Islands, coastal areas of Sardinia and Corsica as well as the island of Cyprus. The Phoenician alphabet is the oldest abjad (consonantal alphabet)—and the ancestor of the Latin alphabet.[7]

Between 3000 and 4000 years ago, Proto-Bantu, spoken in parts of Central and West Africa in the vicinity of Cameroon split off from other Bantoid languages with the start of the Bantu expansion.[8] Well documented languages are primarily preserved in—or from—North Africa, where complex states formed and interacted with other parts of the Mediterranean world. Punic, a variant of Phoenician became a dominant language for perhaps two centuries from the 8th century to 6th century in the Carthaginian Empire.[9] The language maintained lengthy contacts with the rest of the Phoenician sprachraum until the defeat of the empire by Rome in 146 BC, but began to adopt more words and names from neighboring Berber languages over time. The Roman invaders showed appreciation for monumental Carthaginian inscriptions, translating them and giving them as gifts for Berber libraries. A form of the language, referred to by modern scholars as Latino-Punic continued for centuries afterward, with the same word structures and phonology but writing conducted in Latin script.[10]

The nature of Proto-Berber and the emergence of the Berber languages is unclear and may have begun around the time of Mesolithic Capsian culture.[11] Roger Blench suggests that Proto-Berber speakers spread into North Africa from the Nile River valley around 4000 to 5000 years ago, after splitting off from early Afroasiatic.[12] In this model, early Berbers borrowed many words from contact with Carthaginian Punic and Latin. Only the Zenaga language lacks Punic loanwords.

The Nubian civilization flourished along the southern reach of the Nile River, maintaining substantial trade and contact with first Egypt and then Rome. For 700 years people in the Kingdom of Kush spoke the Meroitic language, from 300 BCE to 400 CE. Inscribed in the Meroitic alphabet or hieroglyphics, the language is poorly understood due to a scarcity of bilingual texts. As a result, modern linguists have continuously debated whether the language was Nilo-Saharan or Afroasiatic.[13]

During the Migration Period that brought on the fragmentation of the Roman Empire, Germanic groups briefly expanded out of Europe into North Africa. Speakers of the poorly attested, but presumably East Germanic Vandalic language took control of much of Spain and Portugal and then crossed into North Africa in the 430s, holding territory until the 6th century when they were placed under Byzantine rule following a military defeat in 536.

Americas

The Alaska Native Language Center indicates that the common ancestral language of the Inuit languages and of Aleut divided into the Inuit and Aleut branches at least 4,000 years ago.[14][15]

In Mesoamerica, the Oto-Manguean languages existed by at least 2000 BC, potentially originated several thousand years earlier in the Tehuacán culture of the Tehuacán valley. The undeciphered Zapotec script represents the oldest piece of Mesoamerican writing.[16]

Asia

Throughout ancient times, Asia witnessed the rise of several large, long lasting civilizations. Relatively sparse comparative linguistics research means that the origin of the Dravidian languages now spoken in southern India and a small portion of Pakistan is poorly understood. Proto-Dravidian was likely spoken in India as early as the 4th millennium BC before being partly displaced by Indo-Aryan languages.[17] The Indus Valley civilization is generally interpreted as Dravidian speaking.[18] Indo-Aryan speakers began to take over the plains of northern India spurring Sanskritization after 1500 BC.

Benno Landsberger and other Assyriologists suggest that a hypothetical unclassified language termed Proto-Euphratean may have been spoken in southern Iraq during the Ubaid period from 5300 to 4700 BC, possibly by people belonging to the Samarran culture.[19]

The Gutian people, a group of nomadic invaders from the Zagros Mountains formed the Gutian dynasty and ruled Sumer. The Gutian language is mentioned in Sumerian tablets, along with the names of Gutian kings. The linguist W.B. Henning proposed a possible connection to the Tocharian language based on similar case endings in the kings' names.[20] However, this theory has not gained acceptance by most scholars.[21]

Other poorly attested languages include the Semitic Amorite language spoken by Bronze Age tribespeople. Its westernmost dialect Ugaritic left behind the Ugaritic texts, found by French archaeologists in Ugarit, Syria in 1929. Over 50 Ugaritic epic poems, as well as literary works such as the Baal Cycle (housed in the Louvre) form a large corpus of Ugaritic writing. Sumerian and Akkadian speakers also had contact between the 18th and 4th century BC with speakers of Kassite, living in Mesopotamia and the Zagros Mountains, until they were overthrown by the invading Elamites.

The rise of the Elamite Empire elevated the Elamite language and to prominence between 2600 and 330 BCE. A total of 130 glyphs were adapted from Akkadian cuneiform to serve as Elamite cuneiform. Earlier, between 3100 and 2900 BCE, proto-Elamite writings are the first writings in Iran. Although 20,000 Elamite tablets are known, the language is difficult to interpret and inferred to be a language isolate.[22]

.jpg.webp)

One of the world's primary language families, Hurro-Urartian was spoken in Anatolia and Mesopotomia before going extinct. It is known from the remains of just two languages. Hurrian may have originated in Armenia and spread to the Mitanni kingdom in northern Mesopotamia by the 2nd millennium BC.[23] The language fell victim to the Bronze Age collapse in the 13th century BC along with Ugaritic and Hittite.

"Of Nergal the lord of Hawalum, Atal-shen, the caring shepherd, the king of Urkesh and Nawar, the son of Sadar-mat the king, is the builder of the temple of Nergal, the one who overcomes opposition. Let Shamash and Ishtar destroy the seeds of whoever removes this tablet. Shaum-shen is the craftsman."[24]

In the Caucasus, spoken versions of Proto-Armenian likely appeared around the 3rd millennium BC, amassing loanwords from Indo-Aryan Mitanni, Anatolian languages such as Luwian and Hittite, Semitic languages such as Akkadian and Aramaic, and the Hurrio-Urartian languages. Modern day Armenia was monolingually Armenian speaking by the 2nd century BC.[25] However, written forms of the language do not appear until a translation of the Bible in the 5th century.[26]

To the north and west of Armenia, Proto-Kartvelian began to diverge, with Old Georgian appearing by the 1st millennium BC in the Kingdom of Iberia.[27] Aramaic remained the region's language of religion and literature until the 4th century conversion to Christianity.[28]

Asia Minor was a region of substantial linguistic diversity during ancient times. People in Galatia in central Anatolia spoke the Celtic Galatian language from the 3rd century BC until its extinction around the 4th century CE, or perhaps as late as the 6th century.[29] Phrygian, seemingly a close relative of Greek appeared around the 8th century BC and went out of use in the 5th century CE, with Paleo-Phrygian inscriptions written in a Phoenician-derived script and later writings in Greek script.[30] Hattians in Asia Minor spoke the non-Indo-European agglutinative Hattic language between the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC, before being absorbed by Hittite.[31] Kaskian spoke by Kaskians in the mountains along the Black Sea at a similar time in the Bronze Age, potentially as a proto-version of the later Circassian and Abkhaz language.[32]

The Cimmerians a nomadic Indo-European people likely attacked Urartu a subject state of the Neo-Assyrian Empire around 714 BC, although only a few names survive in Assyrian records.[33] Linguists and anthropologists debate the origins of Turkic peoples and Turkic languages. According to Robbeets, the proto-Turkic people descend from the proto-Transeurasian language community, which lived the West Liao River Basin (modern Manchuria) around 6000 BCE and may be identified with the Xinglongwa culture.[34] They lived as agriculturalists, and later adopted a nomadic lifestyle and started a migration to the west.[34] Proto-Turkic may have been spoken in northern East Asia 2500 years ago.[35]

Linguists disagree about when and where the Tungusic languages in northern Asia arose, proposing Proto-Tungusic spoken in Manchuria between 500 BC and 500 CE, or around the same timeframe in the vicinity of Lake Baikal. (Menges 1968, Khelimskii 1985)[36] Some sources describe the Donghu people recorded between the 7th century and 2nd century BC in Manchuria as Proto-Tungusic.[37] Northern Tungusic contains numerous Eskimo-Aleut words, borrowed no more than 2000 years ago when both languages were evidently spoken in eastern Siberia.[38]

In Central Asia, records in Old Persian indicate that the Sogdian language had emerged by the time of the Achaemid Empire, although no records of Old Sogdian exist.

Reconstructions, textual records and archaeological evidence increasingly shed light on the origins of languages in East Asia. According to archaeological and linguistic evidence published in 2014 by Roger Blench, Taiwan was populated with people arriving from the coastal-fishing Fujian Dapenkeng culture the millet cultivating Longshan culture in Shandong and possibly coastal areas of Guangdong.[39] Taiwan was likely the birthplace of Proto-Austronesian languages that spread across the Pacific, Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia.

Proto-Japonic arrived in Japan from nearby Pacific islands or mainland Asia around the 2nd century BC in the Yayoi Period, displacing the languages of the earlier Jōmon inhabitants which was likely a form of Proto-Ainu.[40] The original forms of Proto-Japonic or Old Japanese are unattested and inferred from linguistic reconstruction. The arrival of Japanese may be related to the emergence of Korean as a language isolate. Proto-Korean may have been spoken in Manchuria before migrating down the Korean Peninsula. One explanation posits that the language displaced Japonic-speakers, triggering the Yayoi migration, while another hypothesis suggests that Proto-Korean speakers slowly assimilated and absorbed Japonic Mumun farmers.[41][42]

Europe

.png.webp)

Beginning between 6500 and 4500 years ago, the ancient common ancestor of the Indo-European languages started to spread across Europe, replacing pre-existing languages and language families.[45] Based on the prevailing Kurgan hypothesis, the original speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language (one of the first and most extensively reconstructed proto-languages since the 19th century) likely lived in the Pontic–Caspian steppe in eastern Europe. These early PIE speakers, centered on the Yamna culture were nomadic pastoralists, with domesticated horses and wheeled vehicles.

Early written records began to appear in Europe, recording a variety of early Indo-European and pre-Indo-European languages. For example, the Corsi people in Corsica left behind place names from the Paleo-Corsican language spoken in the Bronze Age and Iron Age, with potential relationships to Ligurian or Iberian.[46] Elsewhere in the Mediterranean, Iron Age Cyprus and Crete spoke pre-Indo-European Eteocypriot and Eteocretan respectively. Cretan hieroglyphs preserve a written form of Eteocretan.

The Noric language known only from a few fragments of writing in modern Austria and Slovenia appears to be either a Continental Celtic language or Germanic language.[47] Proto-Germanic appeared in southern Scandinavia out of the pre-Proto-Germanic during the Pre-Roman Iron Age. Archaeological remains of the Corded Ware culture might place the arrival of PIE speakers around 4500 years ago in the mid-3rd millennium BCE. Archaeologists and linguists have debated whether or not the Funnelbeaker culture and Pitted Ware culture were Indo-European. Additionally, debates have centered on the Germanic substrate hypothesis, which suggests that early Germanic might have been a creole or contact language based on the presence of unusual words.[48] A large number of Celtic loanwords suggest contact between Proto-Germanic and Proto-Celtic in the Pre-Roman Iron Age.

The Italo-Celtic branch of the Indo-European languages split off in Central and Southern Europe, diverging into the Italic languages (which includes Latin and all subsequent Romance languages) and the Celtic languages. The Urnfield Culture that appeared around 1300 BCE is believed to be the first Proto-Celtic culture followed by the Hallstatt culture in Austria in 800 BC.[49] Celtic languages spread throughout Central Europe, to central Anatolia, western Iberia, the British Isles and current day France, diverging into Lepontic, Gaulish, Galatian, Celtiberian and Gallaecian.

Two Indo-European languages rose to particular prominence in ancient Europe and the surrounding Mediterranean region: Greek and Latin. The emergence of Greek began with Mycenaean Greek.[50] The language and its associated literature and culture had a far reaching impact around the Mediterranean, including areas like southern Italy and the Nile Delta as well as other coastal areas with the establishment of Magna Graecia colonies.

Old Latin is attested from only a few text fragments and inscriptions prior to 75 BCE. As the Roman Empire expanded, Vulgar Latin became a lingua franca for many of its subjects, while Classical Latin was used in upper-class, literary contexts along with Greek.[51] The Golden Age of Latin literature spanned the 1st century BCE and 1st century CE, followed by the two century "Silver Age." The language continued in widespread administrative use through the post-classical period, although Greek superseded Latin in the Eastern Roman Empire. In some cases, languages are completely unattested and only inferred by modern historical linguists. Some Roman accounts suggest that a distinct Indo-European language known as Ancient Belgian was spoken by the Belgae prior to Roman conquest.[52]

During the period of Roman Britain most indigenous Britons continued to speak Brittonic, although British Vulgar Latin was spoken by some. Vulgar Latin was commonplace in many areas conquered by the Roman Empire. Proto-Romanian may have originated from forms of Latin spoken in the province of Dacia Traiana or may have been spoken further south and migrated into the language's current territory. [53]

The Migration Period reshuffled the extent of Germanic, Slavic and invading steppe peoples in Europe and the Near East. The almost entirely unattested Hunnic language was spoken by the invading Huns and used alongside Gothic in conquered areas according to Priscus. [54]

Speculated, but unknown European languages from the time period include Dardani, Phrygian and Pelasgian. Several unattested languages are known from Anatolia. The Trojan language—potentially the same as the Luwian language is entirely unattested. Isaurian language funerary inscriptions from the 5th century CE,[55] Mysian or the Ancient Cappadocian language, which were largely replaced with Koine Greek.[56]

Oceania and the Pacific

In Australia, the earliest Pama-Nyungan languages may have begun to be used and spread across the continent. A 2018 computational phylogenetics study posited an expansion from the Gulf Plains of northeastern Australia.[57] Settlement of Hawaii by Marquesans around 300 CE began the divergence of Eastern Polynesian into the Hawaiian language.[58]

Post-classical period (500 CE–1500 CE)

Africa

During Roman rule in North Africa, Latin made inroads as a language, surviving in some forms as African Romance until the 14th century, even persisting during the first few centuries of Arab-Muslim rule. Together with Berber languages, it was eventually suppressed in favor of Arabic.[59]

Between the 11th and 19th centuries, people in North Africa, as well as Cyprus and Greece commonly communicated in the Mediterranean Lingua Franca from which the widely applied term "lingua franca" is derived. In literal translation to English, lingua franca means "language of the Franks," a general reference to Europeans rather than to Frankish people. Initially, the pidgin drew extensively on Occitano-Romance languages and Northern Italian languages but acquired Portuguese, Spanish, Turkish, French, Greek and Arabic elements over time.[60]

Speakers of the Ngasa language expanded onto the plains north of Mount Kilimanjaro in the 12th century, with mutual intelligibility with Proto-Maasai. But the arrival of Bantu-speaking Chagga over the next five centuries resulted in slow but steady decline of the language.[61]

Although little linguistic evidence exists, Malagasay stories in Madagascar tell of a short-statured zebu-herding people, farming bananas and ginger that were the first inhabitants of the island likely speaking the hypothetical Vazimba language. [62]

Asia

Around the Bay of Bengal, early forms of the Bengali language began to evolve from Sanskrit and Magadhi Prakrit, diverging from Odia and Bihari around 500. Proto-Bengali was spoken by the Sena dynasty and in the Pala Empire.[63][64] In the Sultanate of Bengal it became a court language, acquiring loanwords from Persian and Arabic.[65]

Classical Chinese characters were imported to Japan along with Buddhism and may have been read with the kanbun method. Many texts display Chinese influence on Japanese grammar, such as verbs placed after the object. Sometimes in early texts, Chinese characters phonetically represent Japanese particles. The oldest text is the Kojiki from the 8th century. Old Japanese used the Man'yōgana system of writing, which uses kanji for their phonetic as well as semantic values. Based on the Man'yōgana system, Old Japanese can be reconstructed as having 88 distinct syllables.[66] The use of Old Japanese ended with the close of Nara Period around 794. Early Middle Japanese appeared between the 700s and 1100s with adding labialized and palatalized consonants, before transitioning into Late Middle Japanese up to 1600.

In Vietnam, many interpretations place the Vietnamese language as originating in the Red River valley. However, an alternative interpretation published in 1998 argues that Vietnamese originated further south in central Vietnam and only extended into the Red River region between the 7th and 9th centuries, displacing Tai language speakers.[67]

Distinctive tonal variations emerged during the subsequent expansion of the Vietnamese language and people into what is now central and southern Vietnam through conquest of the ancient nation of Champa and the Khmer people of the Mekong Delta in the vicinity of present-day Ho Chi Minh City, also known as Saigon.

Vietnam gained independence from China in the 10th century, but the ruling classes continued to use Classical Chinese for government, literature and scholarship. As a result, one-third of spoken vocabulary and 60 percent of written words come from Chinese. French sinologist Henri Maspero divided Vietnamese into six phases, with Archaic Vietnamese ending around the 15th century, represented by Chữ Nôm. By this point, the language would have displayed a tone split, with six tones but a lack of contrastive voicing between consonants.[68][69]

On the Korean Peninsula and in Manchuria, the Goguryeo language was spoken in the Goguryeo, the largest and northernmost of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, which existed between 37 BC and 668 CE.[70] The Goguryeo language was one of several Koreanic or Japonic languages spoken in the peninsula in the early modern period. Others include the Gaya language in the Gaya confederacy, the sparsely attested Buyeo in the Buyeo kingdom or the Baekje language, in the Baekje kingdom of southwestern Korea. This last language was closely related to Sillan, which appeared in the kingdom of Silla and gave rise to modern Korean and Jeju.

During the Jin dynasty from 1115 to 1234, the Jurchen language became the first written Tungusic language. Stelae in Manchuria and Korea record writings in the Jurchen script. This script was displaced by the Manchu alphabet with its last recorded occurrence in 1526. Jurchen subsequently evolved into the Manchu language under Nurhaci in the early 1600s with the formation of the Qing dynasty.[71]

The exact origins of the Austroasiatic Khmer language are unclear and attested around 600 CE in Sanskrit texts. Old Khmer (also known as Angkorian Khmer) was spoken as the primary language of the Hindu-Buddhist and jointly Sanskrit-speaking Khmer Empire between the 9th and 13th centuries. Around the 14th century, it lost its official government status and Middle Khmer became substantially influenced by Vietnamese and Thai loan words into the 19th century.[72]

The early origins of the Tai-Kadai language family predate the post-classical period, but written records only began to appear with the publication of the Chinese "Song of the Yue Boatman" which phonetically incorporates words from non-Sinitic languages identified as "Yue." Comparisons in the 1980s and early 1990s drew parallels with the transliterated words to the Zhuang language and the Thai language. [73] Old Thai was spoken for several centuries with a three-way tone distinction for live syllables but transitioned to modern Thai with a loss of voicing distinction and a tone split between the 1300s and 1600s. Offshore, Classical Malay expanded from its initial extent in Northeastern Sumatra to become the lingua franca of the Srivijayan thalassocracy. Some of the earliest writings in the language in Indonesia include the Kedukan Bukit Inscription or the Sojomerto inscription.[74] High Court Malay was spoken by the leadership of the Johor Sultanate and ultimately adopted by the Dutch in the early modern period, but was strongly influenced by Melayu pasar ("market Malay").[75]

Literary forms of languages in the Caucasus continued to grow throughout the post-classical period. For instance, Middle Georgian was in use in the Kingdom of Georgia for national epics such as the 12th century Shota Rustaveli The Knight in the Panther's Skin.

In Central Asia, the Sogdian language emerged as a lingua franca of the Silk Road, acquiring numerous loanwords from Middle Chinese.[76] Manuscripts written in the language were discovered in the early 20th century, indicating use for business as well as Manichaean, Christian and Buddhist texts. It derived its alphabet from the Aramaic alphabet and is the direct ancestor of the Old Uyghur alphabet.

Manuscripts preserve the Tocharian language, a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken in the Tarim Basin of western China between the 5th century and the 8th century and likely extinct by the 9th century. The documents record three closely related languages, called Tocharian A (also East Tocharian, Agnean, or Turfanian), Tocharian B (West Tocharian or Kuchean), and Tocharian C (Kroränian, Krorainic, or Lolanisch). The subject matter of the texts suggests that Tocharian A was more archaic and used as a Buddhist liturgical language, while Tocharian B was more actively spoken in the entire area from Turfan in the east to Tumshuq in the west. Tocharian C is only attested in a few Kharoṣṭhī script texts from Krorän, as well as a body of loanwords and names found in Prakrit documents from the Lop Nor basin.[77]

Kurdish writings were first translated into Arabic in the 9th century. The Yazidi Black Book is the oldest recorded religious writing, appearing sometime during the 13th century.[78] From the 15th to 17th centuries, classical Kurdish poets and writers developed a literary language.

Americas

The Eskimo language family split into the Yupik and Inuit branches around 1,000 years ago.[14][15]

Russian-American linguist Alexander Vovin argues that based on Eskimo loanwords in Northern Tungusic, but not Southern Tungusic languages, these languages originated in eastern Siberia, with the languages interacting around 2000 years ago.[38]

In the 20th and early 21st century, linguists debated whether Nahuatl, the dominant language of the Aztec Empire originated to the north of central Mexico or in the historical Aridoamerica region of what is now the southwestern United States.[79][80] In the northern origin hypothesis, Proto-Nahuan languages emerged around 500 CE and were in contact with the Corachol languages, including the Cora language and Huichol language as its speakers migrated southward. Nahuatl may have appeared after Teotihuacan's fall with some indications that the city would have primarily spoken the Totonacan languages before the arrival of Nahuatl. Potential Nahuatl loanwords in Mayan languages suggest potential contact during the language's formation.[81]

In contact with Mayan Oto-Manguean languages and Mixe-Zoque languages, Nahuatl developed similar relational nouns and calques. Nahuatl rose to prominence beginning in the 7th century and dominated the Valley of Mexico by the 11th century, becoming a lingua franca.

Around 1000 CE, the collapse of the Tiwanaku Empire in what is now Chile and western Bolivia may have caused a period of migration in which the Puquina language influenced the Mapuche language.[82][83]

Europe

During the Migration Period, Germanic speakers swept through Western Europe. Tribes like the Alemanni, Burgundians and Visigoths speaking the Frankish language began the divergence of Vulgar Latin in Gaul into French. In fact, Old French was the first language in the former Roman Empire to diverge from Latin, as attested in the Oath of Strasbourg.[84] Old Low Frankish had its most long lasting effects in the bilingual regions of what is now northern France, resulting in the split between the more Germanic-influenced langue d'oïl and the southern langue d'oc (the separate Occitan language). Germanic languages remained spoken by officials in Neustria and Austrasia into the 10th century.[85]

Off the coast of mainland Europe, Germanic settlers in England began to speak Old English, displacing Old Brittonic with the Northumbrian, Mercian, Kentish and West Saxon dialects.[86] Initially, the language was written in the futhorc runic script until the reintroduction of the Latin alphabet by Irish missionaries in the 8th century. Christianization after 600 added several hundred Latin and Greek loanwords.[87] Some linguists suggest that the arrival of Norsemen and the creation of the Danelaw after 865 may have resulted in a spoken lingua franca with the West Saxon dialect used for literary purposes and the spoken Midland dialect drawing on Norse.[88]

Middle English emerged after 1066 and the prominence of Anglo-Norman and French among the ruling class brought in a substantial number of French words. Literature began to appear in Middle English after the early 1200s.[89] Across the North Sea, Old Dutch diverged from earlier Germanic languages around the same time as Old English, Old Saxon and Old Frisian.[90] It gained ground at the expense Old Frisian and Old Saxon, but the area where it is spoken has since contracted from portions of France and Germany. The Netherlands has one of the only possible remnants of the older poorly attested Frankish language with Bergakker inscription found in Tiel.[91] Old Dutch remained the most similar to Frankish, avoiding the High German consonant shift. Although few records remain in Old Dutch, Middle Dutch and extensive Middle Dutch literature appeared after 1150, together with many dialects and variants, such as Limburgish, West Flemish, Hollandic or Brabantian.[92]

Old Danish appeared around 800 CE and remained "Runic Danish" until the 1100s.[93] For the first 200 years it was almost indistinguishable from early forms of Swedish but differentiated after 1100. Although written records were maintained in Latin, small numbers of early Danish texts were written in the Latin script such as the early 13th century Jutlandic Law and Scanian Law. Royal letters, literature and administrative documents in Danish became more common after 1350 picking up loanwords from Low German. [94]

Norman words from Scandinavia and Old Dutch words entered the French language around the early 1200s.[95] Brythonic-speaking peoples took control of Armorica between the 4th and 7th centuries, spawning the Breton language, which was used by even the ruling class until the 12th century. In the Duchy of Brittany, nobles switched to Latin and then to French in the 15th century, with Breton remaining the language of common people.[96]

The early Romanian language diverged into several different distinct forms in the 10th century, including Istro-Romanian in Istria, Aromanian and Megleno-Romanian. [53] The Albanian language was first attested in writing in Dubrovnik in July, 1284, first the first written document in the language from 1462. [97] Further north and east in the Balkans, early forms of Serbo-Croatian began to emerge from Old Church Slavonic around the 10th century, written in Glagolitic, Latin, Bosnian Cyrillic, Arebica and Early Cyrillic, before becoming a distinct language between the 12th and 16th centuries.[98] Although some early documents, such as the Charter of Ban Kulin appeared as early as 1189, more texts began to crop up in the 13th century like the "Istrian land survey" of 1275 or the Vinodol Codex.[99]

To the north, West Slavic languages began to appear around the 10th century. Polans tribes began to speak early forms of Polish under the leadership of Mieszko I, amalgamating smaller Slavic tribal languages and adopting the Latin alphabet with the Christianization of the area in the late 960s.[100]

During the Norman invasion of Ireland starting in 1169, speakers of the Fingallian Middle English dialect settled in the baronies of Forth and Bargy in southeast Ireland, spawning the Forth and Bargy dialect spoken until the 19th century.[101] The Mongol invasions spurred the Cumans and Jasz people to take shelter in Hungary under the protection of king Béla IV, with their Ossetian Iranian language spoken for another two centuries. The semi-nomadic Pechenegs and potentially also the Cumans spoke the unattested Pecheneg language in parts of current day Ukraine, Romania, and Hungary between the 7th and 12th centuries.[102]

Writings in Hungarian first emerged in 1055 with a first book, the "Fragment of Königsberg" appearing in the 1350s. By the 1490s, 3.2 million people in the Kingdom of Hungary spoke Hungarian although Latin served as the language of religion. The poorly attested Turkic Khazar language was spoken in the Khazar Khanate. Elsewhere, the Old Tatar language was in use in the Volga-Ural region among Bashkirs and Tatars, written in Arabic script and later the İske imlâ alphabet.[103] In 1951, Nina Fedorovna Akulova found the first of a series of birch bark writings in the Old Novgorod dialect from the 11th to 15th centuries. The writings are letters in vernacular Old East Slavic, including high levels of literacy among women and children and showing an absence of later Slavic features like second palatalization. The expansion of the Kievan Rus' led to the presumed Volga-Finnic Muromian language being absorbed by the East Slavs.[104] The same seemingly occurred for the Meshchera and Merya language.[105]

Early modern period (1500 CE–1800 CE)

Africa

Originally referred to as Kingozi, Swahili emerged as a major language in East African trade, with the first written records in Arabic script from 1711.[106][107] Its name comes from Arabic: سَاحِل sāħil = "coast", broken plural سَوَاحِل sawāħil = "coasts", سَوَاحِلِىّ sawāħilï = "of coasts".

Asia

In Japan, Late Middle Japanese was documented by Franciscan missionaries and acquired loanwords from Portuguese, such as "pan" for bread and "tabako" for cigarette. The start of the Edo period in 1603, which would last until 1868 witnessed the rise of Tokyo as the most important city in Japan, shifting linguistic prominence from the Kansai dialect of Kyoto to the Tokyo Edo dialect. Ahom people in the current Indian state of Assam spoke the Ahom language during the rein of the Ahom Kingdom, before shifting to the Assamese language in the 19th century. A Kra-Dai language, it is well documented in court records and religious texts.[108]

Both the Dutch Empire and Portuguese Empire competed for spice trading ports and routes in India, Sri Lanka and elsewhere in Southeast Asia during the 16th and 17th centuries, leading to contact and creolization with native languages. For example, Cochin Portuguese creole was spoken among some Christian families on Vypeen Island, with its last speaker not dying until 2010.[109] On a much larger scale, Sri Lankan Portuguese creole was in use as an island-wide lingua franca for almost 350 years, although fell out of use by anyone besides a few Dutch-descended Burghers.[110] In the southern Philippines, the Sultanate of Sulu granted its territories in the Sulu Archipelago to Spain beginning in the early 1760s, leading to an expansion of the Chavacano Spanish creole, which had originated early around the San José Fortress in Zamboanga City around the mid-1600s.

In the 1600s and 1700s the Dutch East India Company adopted Malay as its administrative and trade language as it grew its influence in the Indonesian Archipelago, due in part to the prominence of the language in the Malaccan Sultanate. This positioned Malay (later Indonesian) to become the official language of the archipelago after independence. Compared to other colonial powers the Netherlands seldom used taught Dutch outside of official circles, although there was an increase in Dutch usage after the Batavian Republic formed the Dutch East Indies in 1779 when the Dutch East India Company went bankrupt.

Europe

Although writings existed in many of Europe's languages in the post-classical period, the invention of the printing press which helped to launch the Protestant Reformation quickly expanded the written form of European languages. For example, previously sparse Uralic languages became well documented. Middle Hungarian appeared in a printed book for the first time in 1533, published in Kraków. The language closely resembled its present form, but retained two past tenses and borrowed many German, French and Italian words, along with vocabulary from Turkish during the Turkish occupation. Other Uralic languages began to appear in print in the 1600s. Estonian language#History Similarly, a German-Estonian Lutheran catechism was published in 1637, followed by the New Testament in 1686 in the southern Estonian.[111]

In Northern Europe, Danish became the language of religion after 1536 due to the Protestant Reformation. Literary forms of the language began to differ more substantially from Swedish and Norwegian, with the introduction of the stød and voicing stop consonants. The first translation of the Bible appeared in Danish in 1550. [112] Similarly, Dutch became more standardized as Modern Dutch around the urban dialects of Holland with the first translation of the Bible into the language.[113] Meanwhile, standardization was put on hold in the southern Spanish Netherlands leading to partial divergence of Flemish.[114]

From the 1600s onward, France was a major world power and an influential hub of European culture. Modern French was standardized around this period and spread worldwide with trading fleets, sugar colonies, deported Huguenots and the Acadian or Québécois settlers of New France.[115] Some Romance languages were slower to become well established as literary languages. Although widely spoken by common people in Wallachia and the Carpathian Mountains, Romanian only rarely appeared in written texts, mostly stemming from the Peri Monastery.[116]

Largely Romance speaking European powers like Portugal, Spain and France began assembling overseas empires in the Americas and Asia in the early modern period, spreading their languages through conquest and trade. English and Dutch also began to disseminate with initially smaller empires. Following the Reconquista, the Inquisition posed a serious threat to some Jewish languages. Shuadit, also known as Judæo-Occitan appeared in French documents back to the 11th century but steeply declined, until the death of its last speaker Armand Lunel much later in 1977.

The Spanish conquest of the Canary Islands in the 1400s drove the Berber Guanche language to extinction. Earlier, in 1341, the Genovese explorer Nicoloso da Recco encountered and partially documented the language, which is also recorded in Punic and Libyco-Berber rock inscriptions.

The Age of Discovery began the creation of new creoles and pidgins among enslaved people and trading communities. Some people in the Solombala port in Arkhangelsk in northern Russia spoke Solombala-English, a Russian-English pidgin, in the 18th and 19th centuries in an unusual example of a trade-related pidgin.

Some of the oldest documented sign languages among deaf communities date to the early modern period. Congenital deafness was widespread in villages in Kent, England, leading to the rise of Old Kentish Sign Language which may be recorded in diaries of Samuel Pepys. Old French Sign Language spoken in Paris in the 18th century competes as one of the oldest European sign languages.

Three Baltic languages, Curonian, Selonian and Semigallian were assimilated to Lithuanian in the 16th century. Crimean Gothic, referenced between the 9th century and 18th century was spoken by Crimean Goths although only written down in any form by the Flemish ambassador Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq in 1562.[117] The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth became one of the largest and most powerful states in Europe, propelling Polish to the status of major regional language through the 1500s, 1600s and 1700s.[118]

North America

Apachean languages like the Navajo language migrated south to the Pueblo language area in around 1500.[119] The establishment of the Spanish Empire in 1519 displaced Nahuatl as the dominant Mesoamerican language, although it remained in widespread use among native people and in government documentation of many settlements in Mexico. The use of tens of thousands of Nahuatl-speaking troops from Tlaxcala spread the language northward and into Guatemala.[120]

Spanish priests created documented grammars of Nahuatl and a Romanized version with the Latin alphabet. In 1570, King Philip II of Spain instituted it as the official language of New Spain, resulting in extensive Nahuatl literature and usage in Honduras and El Salvador. However, the language's situation changed with a Spanish-only decree in 1696 by Charles II of Spain. [121]

As European fishing and trading fleets began to arrive off of North America, they encountered Alqonquin languages speakers. Basque whalers were among the first Europeans to establish sustained contact with native peoples in northeastern North America, particularly around the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. The Algonquian–Basque pidgin emerged at an unknown date, before being last attested in 1710.[122]

In the Saint Lawrence valley, Jacques Cartier encountered speakers of the Laurentian language in the mid-1530s. "Canada" the Laurentian word for village was later adopted for the country Canada. However, the language was driven to extinction at an unknown point in the 16th century likely due to war with the Mohawks.[123] French missionary Chrétien Le Clercq documented the Miꞌkmaq hieroglyphic writing system, which may have been the northernmost example of a native writing system in North America. He adapted the writing system to teach common prayers and the catechism.[124]

In the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth Colony and other parts of southern New England, English settlers interacted with Massachusett language speaking Wampanoag peoples. John Eliot's translation of the Christian Bible in 1663 using the Natick dialect codified the language and it entered widespread use in administrative documents and religious records in praying towns, although the language entered a steady decline toward extinction after King Philip's War.[125]

The Woods Cree and Plains Cree dialects of the Cree language may have diverged from those of other Cree people in northern Canada after 1670 with the introduction of firearms and the fur trade. However, some archaeological evidence suggests that Cree-speaking groups had already reached the Peace River Region of Alberta prior to European contact.[126]

A large influx of Irish laborers to Newfoundland in the 1600s and 1700s led to an outpost of the Irish language in Newfoundland, although the use of the language declined with out-migration to the other Maritime colonies after the collapse of the fishing industry in 1815.[127]

Prior to European arrival, the Arawakan Taíno language displaced most other Caribbean languages but went extinct within 100 years of contact with Spain.[128] Sometime in the 16th century, the poorly attested Guanahatabey language went extinct in western Cuba.[129] Other Caribbean languages died out including the Macorix language in northern Hispaniola and Ciguayo language of the Samaná Peninsula died out in the 16th century, while the Yao language survived in Trinidad and French Guiana, recorded in a single 1640 word list.[130]

In some cases, unique creoles took the place of native languages. For example Negerhollands (spoken until the death of Alice Stevens in 1987) formed as a Dutch-based creole with Danish, English, French and African elements in the Danish colonies of Saint Thomas and Saint John – the current day U.S. Virgin Islands – around 1700.

South America

The oldest written records of the Quechuan languages was created by Domingo de Santo Tomás, who arrived in Peru in 1538 and learned the language from 1540. He published his Grammatica o arte de la lengua general de los indios de los reynos del Perú (Grammar or Art of the General Language of the Indians of the Royalty of Peru) in 1560.[131] At the time of Spanish arrival, Quechua was the lingua franca of the Incan Empire, although it had already spread widely throughout the Andes in the post-classical period before the rise of the Incans.

As result of Inca expansion into Central Chile there were bilingual Quechua-Mapudungu Mapuche in Central Chile at the time of the Spanish arrival.[132][133] In central Chile, Spanish, Mapuche and Quechua may have seen extended bi-lingual or tri-lingual use throughout the 1600s. Quechua was quickly adopted by the Spanish for administrative interactions with native peoples and for church activity.[134] In the late 18th century, colonial officials ended administrative and religious use of Quechua, banning it from public use in Peru after the Túpac Amaru II rebellion of indigenous peoples.[135] The Crown banned even "loyal" pro-Catholic texts in Quechua, such as Garcilaso de la Vega's Comentarios Reales.[136]

Elsewhere in South America, Jesuit priest Antonio Ruiz de Montoya published the Tesoro de la lengua guaraní (Treasure of the Guarani Language / The Guarani Language Thesaurus) in 1639, beginning the process of codifying Guarani as one of the most widely spoken modern native American languages.

19th century

During the 1800s, the Great Divergence which began in the between the 16th and 18th centuries accelerated. Although the Americas became independent between the American Revolution in the 1770s and the end of South American Wars of Independence in the 1820s, the newly independent nations retained their colonial languages including English, Spanish and Portuguese. With the expansion of European colonies in Africa and Asia throughout the 19th century, the rapidly growing Germanic and Romance increasingly expanded into new geographies.

The rise of nationalist, revolutionary and romantic movements in the 1800s led to a surge in interest in formerly low-class regional and peasant languages. For example, beginning with the poems of Kristjan Jaak Peterson, native Estonian literature appeared around 1810, expanding during the Estophile Enlightenment Period.[137]

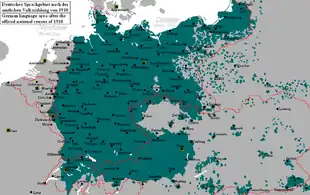

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, during the height of the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, German had expanded to a large portion of Eastern Europe, as well as to a small degree in German colonies in Africa and northern New Guinea. Middle-class people, intellectuals, the wealthy and government officials in Budapest and Bratislava, as well as Baltic cities such as Tallinn and Riga typically spoke German. In 1901, the Duden Handbook codified orthographic rules for German speakers.

Africa

Written records of most African languages are sparse from the Early Modern Period. In the Dutch Cape Colony, Dutch settlers had created an outpost of the Indo-European languages, speaking Cape Dutch among themselves while slaves may have relied on a 'Hottentot Dutch' creole. The combination of these languages began a process of linguistic diversion to create Afrikaans.[138] The Scottish traveler James Bruce who spoke Amharic recorded the Weyto language spoken by hippopotamus hunters around Lake Tana in 1770, but Eugen Mittwoch found the Weyto speaking only Amharic around 1907.[139]

Asia

When France invaded Vietnam in the late 19th century, French gradually replaced Chinese as the official language in education and government. Vietnamese adopted many French terms, such as đầm (dame, from madame), ga (train station, from gare), sơ mi (shirt, from chemise), and búp bê (doll, from poupée).

In Indonesia, the devastating 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora wiped out the poorly attested Papuan Tambora language, which was the westernmost Papuan language in central Sumbawa.[140] The eruption destroyed the town of Tambora, with 10,000 people that possessed bronze bowls, glass and ceramic plates and were among the last cultures left from the pre-Austronesian history of Indonesia.

Multiple small Siberian languages were lost in the late 18th and early 19th centuries including Kott (documented in an 1858 dictionary by Matthias Castren), Yurats, Mator, Pumpokol, and Arin.

Europe

In France, the monarchy may have favored regional languages to some degree to keep the peasantry disunified. During and after the French Revolution, successive governments instituted a policy of stamping out regional languages including Breton, Occitan, Basque and others that persisted into the late 20th century.[141]

The formation of Belgium as a multi-ethnic buffer state in western Europe placed most power in the hands of the French population, centered in the industrialized south. Except for elementary schools in Flanders, all government services were conducted exclusively in French.[142] In the most egregious cases, some innocent Dutch speakers were sentenced to death after being unable to defend themselves in court in French.[143] Although surrounded by Flemish speaking areas, Brussels relatively rapidly became a French majority city—which it remains in the 21st century.[144] During the disputes over language in Ukrainian and Polish areas, Ukrainian Russophiles in Bukovina, Zakarpattia and Halychyna wrote in Iazychie, a blend of Ruthenian, Polish, Russian and Old Slavic.[145]

Russia annexed Bessarabia in 1812, leading to an increase in Russian bilingualism.[146] Other parts of Slavic Eastern Europe also went through a process of codifying languages as part of larger folk- and nationalist movements. For example, Serbian folklorist Vuk Stefanović Karadžić and the Croatian Illyrian movement proposed uniting Serbo-Croatian around the Shtokavian dialect although they split on whether to use the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet or the Croatian Latin alphabet. With the 1850 Vienna Literary Agreement, the two sides settled on a common form of the language which paved the way for the eventual creation of Yugoslavia in the 20th century. [147]

North America

In Newfoundland, the poorly attested Beothuk language went extinct in 1829 with the death of Shanawdithit.[148] The Miami-Illinois language was documented by Jesuit missionary Jacques Gravier in the early 1700s before being displaced to northeastern Oklahoma in the 1800s.[149] Cree was incorporated into the Michif language, Bungi language and Nehipwat language in Saskatchewan and the area around the Red River Settlement in the early 1800s. The fur trade generated these mixed languages, which combine French, Scottish Gaelic and Assiniboine with Cree respectively.[150] Bungi is now virtually extinct, as its features are being abandoned in favor of standard English.[151][152]

Oceania and Pacific

After the British explorer James Cook made contact with Hawaiian peoples, Hawaiian crew members began to serve on European ships. A teenage boy named Obookiah sailed to New England and provided information about the Hawaiian language to missionaries.[153]

South America

With the rising prevalence of Spanish in newly independent Central and South American countries, many native languages entered decline. In the central highlands of Nicaragua, the Matagalpa language went extinct around 1875, while the Pacific slope Subtiaba language disappeared sometime after 1909.[154]

In Tierra del Fuego, the Ona language spoken by the Selk'nam people in Tierra del Fuego went into steep decline due to the Selk'nam genocide.

20th century

Africa

Although displaced to the south by Bantu languages much earlier in their history, many Khoisan languages remained widely spoken through the 19th and early 20th century by native people in southern Africa. Nǁng, a member of the Tuu languages in South Africa exemplifies the decline of many Khoisan languages. Speakers of the language were acculturated to Nama or Afrikaans when speakers moved into towns in the 1930s. The language was then declared extinct and the last people in its community were evicted from Kalahari Gemsbok National Park in 1973. Linguists later discovered 101-year old Elsie Vaalboi and 25 others that could still speak the language in the late 1990s.[155]

The Kwadi language, a click language in southwest Angola went extinct at some point in the 1950s.[156]

At an unknown point in the mid- to late 20th century, Cameroonian languages Duli, Gey, Nagumi and Yeni went extinct, together with the Muskum language in Chad, Kwʼadza and Ngasa in Tanzania or the Vaal-Orange language in South Africa. Two South African languages went extinct with attested dates. Jopi Mabinda, the last speaker of ǁXegwi was murdered in 1988 (although a 2018 report suggests the language may still be spoken in the Chrissiesmeer district) and ǀXam disappeared in the 1910s, but with substantial documentation by German linguist Wilhelm Bleek. Nigerian language extinctions throughout the century include Basa-Gumna by 1987, Ajawa around 1930, and Kpati before 1984, with speakers shifting to Hausa

A language shift to Arabic in Sudan displaced Birgid, Gule and Berti between the mid-1970s and late 1990s. Between 1911 and 1968, Sened language, a Zenati Berber language in Sened, Tunisia fell entirely out of use.[157]

Following the end of French rule in the 1950s and 1960s, newly independent governments in North Africa pursued a policy of Arabization which badly impacted many Berber languages. Millions of Berbers immigrated to France and other parts of Western Europe.

Asia

Between 1900 and 1945 the Japanese sprachraum briefly underwent a rapid expansion as the Empire of Japan took control of Korea and Taiwan, instituting Japanese as the official language in its colonies. Much more briefly, during World War II, Japanese had a short-lived official status in the Philippines, China and occupied Pacific islands. Japanese rule began the process of assimilating and marginalizing the diverse Austronesian languages of Taiwan, which accelerated after the arrival of the Kuomintang government at the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949. In the Andaman Islands, British colonial officials first recognized the Great Andamanese languages in the 1860s. Many of these languages underwent decline and extinction in the 20th century. Aka-Kol, Aka-Bea, Akar-Bale, Oko-Juwoi and Aka-Kede all fell out of use between the early 1920s and early 1950s. Aka-Cari, Aka-Bo, Aka-Jeru and Aka-Kora all survived the 20th century but marked the deaths of their last speakers between 2009 and 2010. The last speakers of Dicamay Agta, one of several Filipino Negrito languages were killed by Ilokano homesteaders in the northern Philippines at some point in the 1950s, 60s or early 70s.

In 1913, the German Jewish aid agency Hilfsverein der deutschen Juden attempted to institute German as the language of instruction for the first technical high school in Palestine prompting the War of the Languages.[158] This sparked a public controversy between those who supported the use of German and those who believed that Hebrew should be the language spoken by the Jewish people in their homeland. The issue was not just ideological: until then, Hebrew was primarily a liturgical language and lacked modern technical terms.[159] The 1910s language debate presaged the revival of Hebrew in an independent Israel after World War II—the only large-scale revival of an extinct language.

Turkish nationalists clashed throughout the century with other language groups in Anatolia. During the Greek genocide, almost all Greek speakers were purged from Turkey and killed or deported to Greece. As a result, speakers of Cappadocian Greek, which had split off of Medieval Greek after the Seljuq Turk victory at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, were forced to leave for Greece. Most Cappadocian Greek speakers shifted quickly to Modern Greek and linguists presumed that the language was extinct by the 1960s. However, in 2005, Mark Janse and Dimitris Papazachariou found that up to 2800 third-generation speakers were still using the language in Northern and Central Greece.[160]

The Turkish Language Association (TDK) was established in 1932 under the patronage of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, with the aim of conducting research on Turkish. Several hundred foreign loanwords were banned from use in media and Arabic and Persian vocabulary fell out of use.

In a renewed wave of linguistic tension following the 1980 Turkish coup the Kurdish language was banned until 1991, remaining substantially restricted in broadcasting and education until 2002.[161][162] At the end of British rule, large portions of Bengal became East Pakistan. The government of the newly formed Dominion of Pakistan, centered in West Pakistan (the current day territory of Pakistan) mandated Urdu as the only official language. This move faced opposition from the Bengali language movement and the government of Pakistan responded to protests in 1952 by killing students at the University of Dhaka.[163] Although language issues were officially settled by 1956 in a new constitution, the subsequent Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 played an important role in further establishing the Bengali language's status in an independent Bangladesh.

Several Siberian languages went extinct in the late 20th century. Valentina Wye was the last speaker of Sirenik Yupik until 1997,[164][165] and Klavdiya Plotnikova was last the living speaker of the Samoyedic Kamassian language until 1989.

Europe

The expansion of the German Empire briefly expanded the German language outside of Central Europe to areas in Africa and New Guinea. In the Austro-Hungarian Empire and German Empire, German was a high status language spoken by upper middle classes and settlers in large parts of current day Poland, Slovakia, and elsewhere in Eastern Europe.

The expulsion of ethnic Germans from Eastern Europe led to a rapid contraction the German Sprachraum, although not a significant erosion of the language. Dialects from areas where German-speakers were fully displaced largely disappeared, including Silesian German or High Prussian. East Pomeranian survives among small numbers of expellees and their descendants in Iowa, Wisconsin and the Brazilian state of Rondonia.[166]

Similarly, up to 350,000 Italian speakers fled Yugoslavia between 1943 and 1960 as part of the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus.[167][168]

North America

The US pursued direct anglicizing policies against native peoples until well into the second half of the 20th century. At the end of the Spanish–American War, 75% of people in the newly acquired Northern Marianas and Guam spoke the Chamorro language. By 2000 only 20% of Guam residents could understand Chamorro. In 1922 all Chamorro schools were closed and Chamorro dictionaries burned—a policy that continued until after World War II.[169] In spite of policies that largely disfavored indigenous languages, the US military undertook strategic use of Navajo code talkers to communicate during World War II, taking advantage of a lack of Navajo dictionaries in existence.[170]

Mexico pursued a policy of Hispanicization, leading to a rapid drop in the number of indigenous language speakers. For example, Nahuatl plummeted from 5% of the population in 1895 to 1.49% in 2000. The Zapatista Army of National Liberation in-part forced new recognition of indigenous languages in the late 1990s, with the creation of the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (CDI) and the Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (INALI), as well as offering bilingual education.[171]

In contrast to losses of regional languages throughout much of North America, the Quebec nationalist movement pushed back in the late 1960s and Canada adopted national bilingualism in 1982. The Charter of French Language in 1977 established French as the sole language of government and education in the Quebec. The number of English speakers in the province, which began declining in the 1960s had dropped by 180,000 since the 1970s in the 2006 census.[172]

Oceania and Pacific

A renewed interest in indigenous cultures after the 1960s and 1970s prompted small scale efforts to revitalize or revive endangered and extinct languages, particularly in Australia and New Zealand. Since 1992, the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre has constructed Palawa kani as a composite of Tasmanian languages.[173]

South America

Similar Hispanicization policies in much of South America reduced many native languages to lower status, as some languages became extinct. In the Atacama Desert in Chile, the last speaker of Kunza language isolate was found in 1949, with the final shift to Spanish completed at some point in the 1950s. The Ona language spoken by Selk'nam people in Tierra del Fuego went extinct around the early 1980s, although some sources suggest a handful of speakers still existed around 2014.[174]

21st century

The end of the Cold War and new globalization into the early 21st century led to large expansions in the number of English speakers, as well as more international education in Mandarin Chinese. Political disruptions changed language use in some areas, with the abandonment of Russian as a second language in some parts of Eastern Europe.

Due to high levels of crime in South Africa, large numbers of Afrikaans speakers emigrated to Australia, Canada, the US and UK throughout the late 1990s and early 21st century. In spite of the loss of state support for the language after the end of apartheid, it remains the second mostly widely spoken language in South Africa, with a growing majority among Coloured people. Census data in 2012 indicated a growing number of speakers in all nine provinces.[175] In Namibia, the percentage of Afrikaans speakers declined from 11.4 percent in the 2001 Census to 10.4 percent in the 2011 Census.[176]

Beginning in 2014, China launched major crackdowns on the Uyghur people of Xinjiang, imprisoning up to one million people in detention camps. In 2017, the government banned all Uyghur language education, instituted a Mandarin only policy and by 2018 had removed Uyghur script from street signs.[177][178]

Nursultan Nazarbayev announced in early 2018 a plan to transition the Kazakh language from Cyrillic to Latin script, estimated to cost 218 billion Kazakhstani tenge ($670 million 2018 US dollars).[179]

Interest in language preservation, revitalization and revival which began in the 19th and 20th centuries accelerated in the 1990s and into the 21st century, particularly with frequent news articles about the rapid decline of small languages. Form 990 non-profit organization filings in the United States indicate several organizations working on endangered languages, but a continued lack of substantial funding. Language categorization and population surveys continue to be undertaken by Glottolog and SIL Ethnologue. Instability in North Africa has brought a surge in some Berber languages. Tuareg rebels revolted against the government of Niger, while reports indicate that tribes in the Nafusa Mountains allied with the National Transitional Council in Libya's civil war are seeking co-official status for the Nafusi language with Arabic.[180]

Although the population of Polish speakers within Poland itself shrank, the Polish language made inroads in other parts of Europe as Polish workers flocked to the UK, Netherlands, France and Germany as guest workers.[181]

Future of language

The future of language has been a popular topic of speculation by novelists, futurists, journalists and linguists since the 19th century. American linguist and author John McWhorter projects that by the early 2100s only 600 to 700 languages will be in widespread daily use, with English remaining as the dominant world language. He imagined a scenario in which languages become more streamlined and blended, giving the examples of "Singlish" in Singapore, Wolof in Senegal, Kiezdeutsch in Germany and "Kebabnorsk" in Norway.[182]

Others argue that English will become only one of several major world languages with an increase in bi-lingualism, given evidence that the number of native speakers of the language is falling. In 2004, consultant and linguistics researcher David Graddol suggested that native English speakers will fall from nine percent to five percent of all language speakers by 2050, with Mandarin Chinese and Hindi-Urdu rising up the list.[183]

In a widely debated assessment, the French investment bank Natixis proposed that French would become the world's most spoken language by 2050, with 750 million speakers in sub-Saharan Africa.[184]

References

- 1 2 Clark, John Desmond (1984). From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa. University of California Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-520-04574-2.

- ↑ Drake, N. A.; Blench, R. M.; Armitage, S. J.; Bristow, C. S.; White, K. H. (2011). "Ancient watercourses and biogeography of the Sahara explain the peopling of the desert". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (2): 458–62. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108..458D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012231108. PMC 3021035. PMID 21187416.

- ↑ Dziebel, German (2007). The Genius of Kinship: The Phenomenon of Human Kinship and the Global Diversity of Kinship Terminologies. Cambria Press. p. 366. ISBN 978-1-934043-65-3. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ↑ Nöth, Winfried (1 January 1994). Origins of Semiosis: Sign Evolution in Nature and Culture. Walter de Gruyter. p. 293. ISBN 978-3-11-087750-2. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ↑ Namita Mukherjee; Almut Nebel; Ariella Oppenheim; Partha P. Majumder (December 2001), "High-resolution analysis of Y-chromosomal polymorphisms reveals signatures of population movements from central Asia and West Asia into India", Journal of Genetics, Springer India, 80 (3): 125–35, doi:10.1007/BF02717908, PMID 11988631, S2CID 13267463,

... More recently, about 15,000–10,000 years before present (ybp), when agriculture developed in the Fertile Crescent region that extends from Israel through northern Syria to western Iran, there was another eastward wave of human migration (Cavalli-Sforza et al., 1994; Renfrew 1987), a part of which also appears to have entered India. This wave has been postulated to have brought the Dravidian languages into India (Renfrew 1987). Subsequently, the Indo-European (Aryan) language family was introduced into India about 4,000 ybp ...

- ↑ Rodrigues, Aryon Dall'Igna (2007). "As consoantes do Proto-Tupí". In Ana Suelly Arruda Câmara Cabral, Aryon Dall'Igna Rodrigues (eds). Linguas e culturas Tupi, p. 167–203. Campinas: Curt Nimuendaju; Brasília: LALI.

- ↑ Markoe, Glenn E., Phoenicians. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22613-5 (2000) (hardback) p. 111.

- ↑ Newman (1995), Shillington (2005)

- ↑ Jongeling, Karel; Kerr, Robert M. (2005). Late Punic Epigraphy: An Introduction to the Study of Neo-Punic and Latino-Punic Inscriptions. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-1614-8728-6.

- ↑ "Punic". Omniglot. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ↑ "DDL : Evolution – Themes and actions". Ddl.ish-lyon.cnrs.fr. Retrieved 2015-07-14.

- ↑ Blench, Roger. 2018. Reconciling archaeological and linguistic evidence for Berber prehistory.

- ↑ Kirsty Rowan. "Meroitic – an Afroasiatic language?". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.691.9638.

- 1 2 Jacobson, Steven (1984). Central Yupik and the Schools – A Handbook for Teachers. Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

- 1 2 Stern, Pamela (2009). The A to Z of the Inuit. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. pp. xxiii. ISBN 978-0-8108-6822-9.

- ↑ Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America (Oxford Studies in Anthropological Linguistics, 4). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509427-5. P. 159

- ↑ Steven Roger Fischer (3 October 2004). History of Language. Reaktion books. ISBN 9781861895943.

It is generally accepted that Dravidian – with no identifiable cognates among the world's languages – was India's most widely distributed, indigenous language family when Indo-European speakers first intruded from the north-west 3,000 years ago

- ↑ Mahadevan, Iravatham (6 May 2006). "Stone celts in Harappa". Harappa. Archived from the original on 4 September 2006.

- ↑ История древнего Востока, т.2. М. 1988. (in Russian: History of Ancient Orient, Vol. 2. Moscow 1988. Published by the Soviet Academy of Science), chapter III.

- ↑ Henning, W.B. (1978). "The first Indo-Europeans in history". In Ulmen, G.L. (ed.). Society and History, Essays in Honour of Karl August Wittfogel. The Hague: Mouton. pp. 215–230. ISBN 978-90-279-7776-2.

- ↑ Mallory, J.P.; Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 281–282. ISBN 978-0-500-05101-6.

- ↑ Stolper, Matthew W. 2008. Elamite. In The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Aksum. p. 47-50.

- ↑ Hurrian language – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ↑ "Royal inscriptions". urkesh.org.

- ↑ Strabo, Geographica, XI, 14, 5; Հայոց լեզվի համառոտ պատմություն, Ս. Ղ. Ղազարյան։ Երևան, 1981, էջ 33 (Concise History of Armenian Language, S. Gh. Ghazaryan. Yerevan, 1981, p. 33).

- ↑ Baliozian, Ara (1975). The Armenians: Their History and Culture. Kar Publishing House. p. 65.

There are two main dialects: Eastern Armenian (Soviet Armenia, Persia), and Western Armenian (Middle East, Europe, and America) . They are mutually intelligible.

- ↑ Braund, David (1994), Georgia in Antiquity; a History of Colchis and Transcaucasian Iberia, 550 B.C. – A.D. 562, p. 216. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-814473-3

- ↑ Tuite, Kevin, "Early Georgian", pp. 145–6, in: Woodard, Roger D. (2008), The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-68496-X

- ↑ Koch, John T. (2006). "Galatian language". In John T. Koch (ed.). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. Vol. III: G—L. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 788. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

Late classical sources—if they are to be trusted—suggest that it survived at least into the 6th century AD.

- ↑ Brixhe, Cl. "Le Phrygien". In Fr. Bader (ed.), Langues indo-européennes, pp. 165–178, Paris: CNRS Editions.

- ↑ Akurgal, Ekrem – The Hattian and Hittite Civilizations ( p.4 and p.5)

- ↑ George Hewitt, 1998. The Abkhazians, p 49

- ↑ Yamauchi, Edwin M (1982). Foes from the Northern Frontier: Invading Hordes from the Russian Steppes. Grand Rapids MI USA: Baker Book House.

- 1 2 Robbeets, Martine (2017). "Austronesian influence and Transeurasian ancestry in Japanese". Language Dynamics and Change. 7 (2): 210–251. doi:10.1163/22105832-00702005. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002E-8635-7.

- ↑ Janhunen, Juha (2013). "Personal pronouns in Core Altaic". In Martine Irma Robbeets; Hubert Cuyckens (eds.). Shared Grammaticalization: With special focus on the Transeurasian languages. John Benjamins. p. 223. ISBN 9789027205995.

- ↑ Immanuel Ness (29 Aug 2014). The Global Prehistory of Human Migration. John Wiley & Sons. p. 200. ISBN 9781118970584.

- ↑ Barbara A. West (19 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase. p. 891. ISBN 9781438119137. Retrieved 26 Nov 2016.

- 1 2 Vovin, Alexander. 2015. Eskimo Loanwords in Northern Tungusic. Iran and the Caucasus 19 (2015), 87–95. Leiden: Brill.

- ↑ Blench, Roger. 2014. Suppose we are wrong about the Austronesian settlement of Taiwan? m.s.

- ↑ Wade, Nicholas (4 May 2011). "Finding on Dialects Casts New Light on the Origins of the Japanese People". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ↑ Janhunen, Juha (2010). "RReconstructing the Language Map of Prehistorical Northeast Asia". Studia Orientalia (108).

... there are strong indications that the neighbouring Baekje state (in the southwest) was predominantly Japonic-speaking until it was linguistically Koreanized.

- ↑ Vovin, Alexander (2013). "From Koguryo to Tamna: Slowly riding to the South with speakers of Proto-Korean". Korean Linguistics. 15 (2): 222–240.

- ↑ Kinder, Hermann (1988), Penguin Atlas of World History, vol. I, London: Penguin, p. 108, ISBN 0-14-051054-0.

- ↑ "Languages of the World: Germanic languages". The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago, IL, United States: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1993. ISBN 0-85229-571-5.

- ↑ Powell, Eric A. "Telling Tales in Proto-Indo-European". Archaeology. Retrieved 2017-07-30.

- ↑ Mastino, Attilio (2006). Corsica e Sardegna in età antica, UnissResearch Archived 2013-10-19 at the Wayback Machine(in Italian)

- ↑ Encyclopédie de l'arbre celtique, Vase de Ptuj. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ↑ Kinder, Hermann; Werner Hilgemann (1988). The Penguin atlas of world history. Vol. 1. Translated by Ernest A. Menze. Harald and Ruth Bukor (Maps). Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 109. ISBN 0-14-051054-0.

- ↑ Chadwick with Corcoran, Nora with J.X.W.P. (1970). The Celts. Penguin Books. pp. 28–33.

- ↑ Newton, Brian E.; Ruijgh, Cornelis Judd (13 April 2018). "Greek Language". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Allen, W. Sidney (1989). Vox Latina. Cambridge University Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 0-521-22049-1.

- ↑ Rolf Hachmann, Georg Kossack and Hans Kuhn. Völker zwischen Germanen und Kelten, 1986, p. 183-212.

- 1 2 Andreose & Renzi 2013, p. 287.

- ↑ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 382.

- ↑ Honey, Linda (5 December 2016). "Justifiably Outraged or Simply Outrageous? The Isaurian Incident of Ammianus Marcellinus". Violence in Late Antiquity: Perceptions and Practices. Routledge. p. 50. ISBN 9781351875745.

- ↑ Frank Trombley, Hellenic Religion and Christianization c. 370–529 2:120

- ↑ Bouckaert, Remco R., Claire Bowern & Quentin D. Atkinson (2018). The origin and expansion of Pama–Nyungan languages across Australia. Nature Ecology & Evolution volume 2, pages 741–749 (2018).

- ↑ Kimura & Wilson (1983:185)

- ↑ Peter C. Scales, The Fall of the Caliphate of Córdoba: Berbers and Andalusis in Conflict (Brill, 1994), pp. 146–47.

- ↑ La «lingua franca», una revolució lingüística mediterrània amb empremta catalana, Carles Castellanos i Llorenç

- ↑ Leeman, Bernard and informants. (1994). 'Ongamoi (KiNgassa): a Nilotic remnant of Kilimanjaro'. Cymru UK: Cyhoeddwr Joseph Biddulph Publisher. 20pp.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Vazimba". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ nimmi. "Pala Dynasty, Pala Empire, Pala empire in India, Pala School of Sculptures". Indianmirror.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ↑ Oberlies, Thomas (2007). "Chapter Five: Aśokan Prakrit and Pāli" Archived 7 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. In Cardona, George; Jain, Danesh. The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- ↑ Rabbani, AKM Golam (7 November 2017). "Politics and Literary Activities in the Bengali Language during the Independent Sultanate of Bengal". Dhaka University Journal of Linguistics. 1 (1): 151–166. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017 – via www.banglajol.info.

- ↑ Shinkichi Hashimoto (February 3, 1918)「国語仮名遣研究史上の一発見―石塚龍麿の仮名遣奥山路について」『帝国文学』26–11(1949)『文字及び仮名遣の研究(橋本進吉博士著作集 第3冊)』(岩波書店|Notes= Texts written with Man'yōgana use two different kanji for each of the syllables now pronounced き ki, ひ hi, み mi, け ke, へ he, め me, こ ko, そ so, と to, の no, も mo, よ yo and ろ ro)。

- ↑ Chamberlain, James R. (2000). "The origin of the Sek: implications for Tai and Vietnamese history". In Burusphat, Somsonge (ed.). Proceedings of the International Conference on Tai Studies, July 29–31, 1998 (PDF). Bangkok, Thailand: Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development, Mahidol University. pp. 97–127. ISBN 974-85916-9-7. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ↑ Maspero, Henri (1912). "Études sur la phonétique historique de la langue annamite" [Studies on the phonetic history of the Annamite language]. Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (in French). 12 (1): 10. doi:10.3406/befeo.1912.2713.

- ↑ Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà (2009), "Vietnamese", in Comrie, Bernard (ed.), The World's Major Languages (2nd ed.), Routledge, pp. 677–692, ISBN 978-0-415-35339-7.

- ↑ Bellwood, Peter (2013). The Global Prehistory of Human Migration. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781118970591.

- ↑ Tillman, Hoyt Cleveland, and Stephen H. West. China Under Jurchen Rule: Essays on Chin Intellectual and Cultural History. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995, pp. 228–229. ISBN 0-7914-2274-7. Partial text on Google Books.

- ↑ Sak-Humphry, Channy. The Syntax of Nouns and Noun Phrases in Dated Pre-Angkorian Inscriptions. Mon Khmer Studies 22: 1–26.

- ↑ Holm 2013, pp. 784–785.

- ↑ "Bahasa Melayu Riau dan Bahasa Nasional". Melayu Online. Archived from the original on 22 November 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ↑ "Bahasa Indonesia: Memasyarakatkan Kembali 'Bahasa Pasar'?". Melayu Online. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ↑ Rachel Lung (7 September 2011). Interpreters in Early Imperial China. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 151–. ISBN 978-90-272-8418-1.

- ↑ Kim, Ronald I. (2018). "One hundred years of re-reconstruction: Hittite, Tocharian, and the continuing revision of Proto-Indo-European". In Rieken, Elisabeth (ed.). 100 Jahre Entzifferung des Hethitischen. Morphosyntaktische Kategorien in Sprachgeschichte und Forschung. Akten der Arbeitstagung der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft vom 21. bis 23. September 2015 in Marburg. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag. p. 170 (footnote 44). Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ↑ Jonh S. Guest, The Yazidis: A Study In Survival, Routledge Publishers, 1987, ISBN 0-7103-0115-4, ISBN 978-0-7103-0115-4, 299 pp. (see pages 18, 19, 32)

- ↑ Merrill et al. 2010.

- ↑ Kaufman & Justeson 2009.

- ↑ Fowler (1985:38); Kaufman (2001)

- ↑ Dillehay, Tom D.; Pino Quivira, Mario; Bonzani, Renée; Silva, Claudia; Wallner, Johannes; Le Quesne, Carlos (2007) Cultivated wetlands and emerging complexity in south-central Chile and long distance effects of climate change. Antiquity 81 (2007): 949–960