| Exploradores de España (Spanish Boy Scouts) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Exploradores de España Badge (1912-1921) | |||

| Country | Spain | ||

| Founded | 1912 | ||

| Defunct | 1940 | ||

| Founder |

| ||

| President | Juan Antonio Dimas (Lobo Gris) | ||

|

| |||

The Exploradores de España was a Spanish Scout association founded by Cavalry captain Teodoro Iradier y Herrero in 1912 and inspired by the boy scouts of Robert Baden-Powell, whose objective was physical, moral, civic and patriotic education. In its early years it had a rapid growth and expansion. The association was a founding member of the World Organization of the Scout Movement in 1922,[1][2] which it belonged to until 1938.[3]

After a royal audience granted to Iradier in early June 1912, it received the personal support of King Alfonso XIII of Spain and the authorities of the time.[4] However, it was opposed by the Catholic Church and certain cultural sectors that viewed with suspicion the institutional evolution, which was highly militarized and subordinated to the direct service of power.[5]

After a brief period of decline between 1914 and 1919, it received support from the Directorio Militar of Primo de Rivera during the 1920s, experiencing a change of educational direction and, consequently, a strong increase in personnel, in what could be considered the golden age of the institution.[6] In addition to such times, the exploradores provided a renewed vision of how to practice pedagogy: the formation of the character of youth, and instruction in religious values and citizenship.[7]

After the Spanish Civil War, the organization was declared in suspension of activities by ministerial order of 22 April 1940, as its dependence on international organizations was considered "intolerable".[8]

Background

The first known attempt of scouting in Spain began in Barcelona. It was the initiative of Pedro Roselló Axet, Cavalry captain, friend and colleague of Teodoro Iradier; together with Ramón Solé i Lluch—an enthusiastic worker of scouting—and Narcís de Romaguera, among others.[9][10] Pedro Roselló's objective was to achieve a healthy youth, physically, morally and spiritually. Thus the Exploradores de Barcelona were born in 1911, officially constituted in 1912[11] and that in 1913 would become part of the Exploradores de España.[12][13] In 1914, they amounted to 1064 members, organized in twenty-two groups.[14] During its decline, in 1916, the number of members dropped to less than 450 members.[15]

Parallel to the Exploradores Barceloneses, there were other less successful Catalan initiatives such as the Jovestels de Catalunya of Ignasi Ribera-Rovira in 1912, related to the Republican Nationalist Federal Union,[16] and with two groups, Cataluña and Canigó.[17] Also the Exploradores Republicanos (radical boy scouts),[18] organization under the aegis of Alejandro Lerroux[19] and led in Barcelona by Antonio Cruz.[20]

Foundation

Teodoro Iradier received the support of King Alfonso XIII and from 1911, with the help of the publicist Arturo Cuyás Armengol, a public awareness campaign was launched and the youth movement was very well received, especially among the wealthier classes.[21] In Iradier's words: "Scouting is life in the open, the learning of useful things, the doing of good works",[22] as well as "the explorador of today will be the practical man of tomorrow" and "will proudly hold the title of transformer of our homeland".[23]

Once obtained the necessary support and approved its statutes by the Civil Government of Madrid on 30 July 1912,[24] Iradier relocated to his hometown. On 11 August 1912 he founded the first Exploradores de España troop, the Exploradores de Vitoria, and the Madrid Troop in October.[25]

Members of the first National Council

By the end of 1912, the first steering committee and executive council of the institution was constituted,[26] including the following personalities:

President

- Duque de Tamames (honorary colonel, dean of the Spanish Nobility, grandee of Spain and senator of the Kingdom).

Vice-Presidents

- Antonio Tovar y Marcoleta (Major General)

- Francisco García Molinas (doctor in Medicine, first deputy mayor and secretary of the Senate)

- Baldomero González Álvarez (physician and academic)

Treasury

- Salvador García Dacarrete (First Officer of the Military Quartermaster's Office)

Advertising and Resources Section

- Vicente Vera y López (professor and assistant secretary of the Real Sociedad Geográfica de España)

- Leopoldo Serrano y Domínguez (Minister of the Tribunal de Cuentas)

Organization Section

- José Castaño de la Paz (Captain of the Estado Mayor)

Instruction Section

- Arturo Cuyás (editor-in-chief of El Hogar Español)

- Javier Cabezas Montemayor (inspector of the Patronato de Protección a la Infancia)

Secretary - General Commissioner

- Teodoro de Iradier (Cavalry captain)

Deputy Secretary

- Casimiro Juanes (engineer of roads, canals and ports)

Expansion, supporters and detractors

On 27 April 1913, 2397 exploradores gathered at the Atlético Madrid field for the promise ceremony, with the attendance of the kings of Spain. The Madrid districts of Buenavista, with three groups; Palacio, with six groups; Latina, with two; Centro, with four; Congreso, with three; Inclusa with two; Hospicio, with three; and Universidad, Hospital and Chamberí, with two each[27] That same year, the first issue of the magazine El Explorador,[28] and Pedro Rosselló's Exploradores Barceloneses became part of the Exploradores de España.[29]

In January 1914, there were already 68 Exploradores en España committees and in July the first national camp was held in Riofrío, Real Sitio de San Ildefonso,[30] in which 580 troops from 18 towns from Aragón, Asturias, Barcelona, Burgos, Galicia, Granada, Guadalajara, Madrid, Murcia, Palencia, Salamanca, Santander, Valladolid and Zamora participated. In December the first census appeared, with 18 024 young men and 115 committees throughout Spain. That same year, the Royal Order of February 12 of the Ministry of Public Instruction and Fine Arts granted legal personality to the Asociación de los Exploradores de España.[31][32]

José María Quintana Cabanas cites a period of disagreements with the Church which, as was happening in other countries, accused the Explorers of Spain of naturalism and of hindering the religious practices of children.[8] On the other hand, a series of internal conflicts in the organization forced the resignation of Iradier as secretary-commissioner in February 1915 and, in solidarity with him, also that of the president of the explorers, José Messía y Gayoso, duke de Tamames.[33] As reported in El Explorador:

...the General Commissioner Mr. Teodoro de Iradier, dissatisfied with the direction taken by the Institution, resigns from all his posts and, as a consequence, the resignation of His Excellency the Duke of Tamames, President of the Association.[34]

The Duke of Tamames was reinstated on 11 March 1915, at the request of the national assembly, a position he held until his death in 1917, being replaced by Julio Quesada-Cañaveral. The new governing board was formed by Antonio Trucharte Samper as secretary, Arturo Cuyás as general commissioner and Teodoro Iradier y Herrero as member.[35]

The distrust was not limited to the ecclesiastical sphere, since educational renovationists also distrusted the excessive militarization of the exploradores in their particular vision of scouting.[36]

In 1913, the Al-lots Guaites sponsored by the Catholic Church were created in Mallorca, which would be integrated into the Exploradores de España in 1918.[37] The Mallorcan exploradores, a section of the Mallorcan Catholic Sports Federation, were led by their founder and organizer, the priest Francesc Sureda Blanes.[38]

In 1915 King Alfonso XIII gave the explorers a plot of land on El Pardo mountain to be used as a permanent camp. That same year the first group of sea scouts appeared in Santander,[39] también con apoyo real.[40] In 1917 the king accepted the honorary presidency of the Scouts of Spain.[41]

In 1920, a contingent of Exploradores de España participated in the first world jamboree at Olympia, London. That same year, there were 305 exploradores committees. It was at that time that the confessionality of the institution was defined—which grew and evolved secularly—[42] and the image and the theoretical and pedagogical knowledge of the scout movement in Spain was improved.[43] On 26 February 1920 the association received the consideration of national by Royal Decree.[44]

After international recognition in 1922, the government decided to reorganize the institution, but without dispensing with the centralist and pro-government character that characterized it.[45] On 13 September 1923 a coup d'état by the captain general of Catalonia, Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, would give way to a military dictatorship. Primo de Rivera, father of exploradores and of whose National Council he was a founding member, granted it greater protection in all areas.[46] In those early years of the Dictatorship, Francisco García Molinas, vice president of the National Council, made the Exploradores de España available to the Government as a means for civic education, a school of citizenship for the "improvement of the race" and an example of solidarity between classes. The idea was well received by the Directorio Militar, which began to propose a national plan of physical and pre-military training among young people, and by royal order of May 1925, a commission of various ministerial departments and civilian entities was created for this purpose.[47] The more progressive sectors did not look favorably on the dictator's support; in the words of Alexandre Galí, the exploradores were perceived as an instrument of the dictatorship and the regime's support distanced them even further from the people.[48]

In 1926 Antonio Trucharte Samper died unexpectedly, his absence provoked an internal crisis in the national council of the association.[49] He was replaced by Luis de la Gándara Marsella, who also died suddenly two years later, in 1928.[50]

In the mid-1920s, the English engineers who had come to work in the Riotinto Mines gave a very important push for the creation and consolidation of scouting in the Huelva area.[51] The golden age in Minas de Riotinto was under the leadership of Francisco (Frank) Timmis (d. 1931), president of the Local Council, English national and great connoisseur of Baden-Powell's work. In 1924, the Alto Patronato de Exploradores en Minas de Riotinto, under the Schools Department of the Rio Tinto Company Limited, left the organization in the hands of Timmis and in a short time they had about 300 members among the students of the RTCL schools where they learned to march, practiced sports, olympic gymnastics, first aid, and were inculcated with scouting principles.[52] Also in the north, San Sebastián and Bilbao, whose exploradores troops had been active since 1913,[53][54] received help and saw remarkable growth with contributions from Englishmen working in the mines of the Estuary of Bilbao.[51]

Emili Beüt led the changing trend towards Baden-Powell scouting in Valencia, advocating a less centralized and militaristic institution. According to Beüt, certain sectors intended to perpetuate the image of the scouts as children's battalions.[55] He was the originator of the Federación Regional Valenciana de Exploradores in 1927.[56]

There were also intellectuals who showed some opposition to the exploradores, among them Miguel de Unamuno, who stated in the magazine Nuevo Mundo on 16 November 1917, that he did not believe in the pedagogical function of the boy scouts because of their "contrived character", an article answered by J. Cueto in El Explorador;[57] such a manifesto provoked an outcry from the institution and a reply from Juan Antonio Dimas (Lobo Gris) of the Águilas Troop (Murcia) on November 19. In 1921, Unamuno published again with the same argument, proposing football for the formation of young people, as "spontaneous, free, and less intervened".[46][58][59]

Juan Antonio Dimas was the first to speak of "Scouting pedagogy",[8] and would be the first national Scoutmaster in 1932 at the suggestion of Baden Powell himself.[60][61]

In 1930, initial steps were taken to organize a guide association in Spain, headed by María Abrisqueta de Zulueta,[62] of San Sebastián. Until its definitive foundation in September 1933, as Asociación de Muchachas Guías,[63] the guide companies were protected and promoted by the Exploradores de España. María Abrisqueta, who had been proposed from the beginning as national commissioner of guides, resigned in June 1935 from her responsibilities in the association.[64]

1929 National Jamboree and 2nd Republic

The National Jamboree of Barcelona was held between 21 August and 3 September 1929, benefiting from the momentum caused by the International Exposition. It was the first of international character to be organized in Spain and also the last, held in Montjuïc, with the participation of 2000 scouts, Spanish and foreigners, from fourteen countries:[65] England, France, Hungary, Germany, Tangier, Poland, Chile, Holland, Sweden, Romania, Scotland, Australia, Brazil and Portugal. Most were stopping over from the Birkenhead World Jamboree held that same year. During the event, a Muslim explorer from Tangier, Mustafa-ab-el-Kader, died after an accident that made headlines at the time.[66][67][68][69]

In 1927, Josep Maria Batista i Roca founded the Minyons de Muntanya,[70] and in the early 1930s, the first Catholic confessional groups appeared, which would be constituted as the Scouts Hispanos in 1934 by the priest Jesús Martínez and a former commissioner Mario González Pons—an institution of ephemeral existence.[71]

Also in 1930, Isidoro de la Cierva (Lobo Blanco) became General Commissioner and Juan Antonio Dimas became Deputy General Commissioner of the National Council.[72]

In 1931, the Spanish Republic was proclaimed and the insignia was modified almost immediately, removing the fleur-de-lis present since 1922, and replacing it with a hand in a scout salute.[73] The president of the National Council, Francisco García Molinas, sent a telegram to the groups ordering "compliance with the constituted powers."[74] By Decree of the provisional Government of the Republic, it was transmitted on 21 May 1931 to the Ministry of Public Instruction and Fine Arts how many attributions corresponded to the Presidency, in relation to the Exploradores de España.[75]

In April 1933, the first five general commissioners were elected following the change of statutes to adapt them to the new democratic regime:[76][77]

- Juan Antonio Dimas

- José Miaja Menant

- Francisco Medina Ample

- Carlos Cifuentes Rodríguez

- Severo Montalvo Córdoba

Despite the reluctance of the most radical Republicans, who criticized the link between the Exploradores de España and the Bourbon monarchy, Niceto Alcalá Zamora, president of the Republic, accepted in 1933 the honorary presidency of the Exploradores de España.[78] According to Francisco Armada Muñoz, the influence of General José Miaja Menant, general commissioner of the Exploradores and of Republican ideology, had much to do with this decision.[79]

The politician and founder of the exploradores de Granada, Luis López-Dóriga, was the translator of Baden-Powell's Scouting for Boys from English into Spanish in 1934, a work that was never published in Spain.[80]

On 2 May 1936 the President of the Republic officially recognized the Asociación Nacional de Exploradores de España and confirmed the statutes presented in July 1932.[81]

Assault on the Exploradores de Barcelona headquarters and the Catalan split

After the incidents of the proclamation of the Catalan Republic on 14 April 1931, the Catalan identity character and the detachment to the national centralist associations in certain sectors of Catalonia—as was the case of the Spanish boy scouts—were accentuated and developed. In the opinion of Félix Cucurull, "as a consequence of the oppression to which it was subjected",[82] legacy of the Directiorio Militar, considering that "a nationalist sentiment such as the Catalan one could be sacrificed by violence and silence".[83] However, Juan Peiró blamed such behavior on the fact that "the freedom of Catalonia was not achievable except by a procedure of direct action", the result of "centuries of submission under the yoke of magistrates, military and stowaways incapable of understanding the soul of the Catalans".[84]

One of the most hostile precedents was the assault on the headquarters of the exploradores loyal to the national association on 28 April 1930,[85] starring a sector of the jovent republicà (republican youth)[16][86] during a student strike, causing the Exploradores Barceloneses to lose their flag. According to the available documentation on Catalan scouting from the National Archive of Catalonia, in 1933 the most Catalanist sector, openly politicized left-wing and akin to the nationalist postulates of the time, the Boy Scouts de Catalunya was organized as an association of regional character whose strong core would be the protagonist of a major split of the Exploradores de España in Catalonia.[87] Among the demands of the breakaway group was to dispense with the use of the national flag in the activities of the association and total independence in its institutional relations with the International Scout Bureau in London.[88] In 1932, in a decentralizing attempt, the Catalan grouping had previously been constituted as the Federación de los Boy Scouts de Cataluña, linked to the Exploreradores de España;[7] On 22 February 1933 Carlos Cifuentes Rodríguez resigned as commissioner of Catalonia, and Narcís de Romaguera, head of the Catalanist faction, was dismissed by the National Council which refused to cede autonomy. The fracture was consummated, backed by historical figures of the time of Pedro Roselló, Ramón Soler and Jaume Roca.[89] The honorary presidency of the new institution was offered to Francesc Macià, president of the Generalitat de Catalunya.[90] After the split, the Exploradores de España en Cataluña were reduced to a minimum, their presence limited to the municipalities of Barcelona and Tarrasa, and the autonomous English and French groups.[91][89]

The general commissariat reported its position in September 1934, in press notes and in its informative organ El Explorador:

The Asociación Nacional de los Boy Scouts españoles (Exploradores de España) hereby announces that the Boy Scouts de Catalunya have no right to use this name, since they have not been recognized and do not belong to the World Association of the Boy Scouts, nor to its Spanish branch. The Boy Scouts españoles de Barcelona, like those of the rest of Spain, absolutely alien to all partisanship, scrupulously abstain from participating in political acts, of any kind whatsoever, which is also forbidden by their Statutes.[92]

In October 1934, after the reorganization of the exploradores in Catalonia, the magazine El Explorador announced the new board of directors:

- Provincial Commissioner and President of the Federation: Carlos Cifuentes Rodríguez.

- Local Commissioner: Ignacio Solanas Gracia.

- Members: Joaquín Bonet Irriborren, Sergio Solanas Gracia, Carlos Kuhn Steinhausen, Eduardo Fernández de la Reguera, Aurelio García Cordoncillo, Jerónimo Tevar Cruz, Ramón Lizcano de la Rosa, Enrique Schepelmann and José María Blasco Pujades.[93]

In any case, it was evident that the perseverance of the exploradores in integrating themselves among the Catalan excursionist movement through their participation in the Campaments Generals de Catalunya—an annual event of the time initiated in 1928— and it indicates that they were neither militant Spanishists nor conscious agents of primoriverismo, as concludes Albert Balcells at the end of the chapter on the scouts and the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera in his book L'escoltisme català (1911-1978).[94]

Subsequently, as a result of the participation of prominent members of mainly Minyons de Muntanya and Boy Scouts de Catalunya in the events of October 6,[95] an order appeared in the Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya annulling any recognition and benefit to the local scouting institutions. A situation that would not be normalized until the pardons of 1936:[96]

Considering the significance and patriotic purposes of the Asociación de los Exploradores de España (Federación de Boy Scouts de Cataluña), established in this region without interruption since the year 1912, by virtue of being part of the International Association of Boy Scouts, which allows them to operate beyond their frontiers, carrying Spain's name and flag to other nations in the great universal concentrations known by the name of Jamborees, as it happened in the one verified in 1933 in Hungary (Godollo), where several organizations that tried to do so without belonging to the International Association were forbidden to stay.

Considering in a very particular way the circumstances of holding the honorary presidency of the said Association, His Excellency the President of the Republic, allows this Presidency of the Generalitat to recognize its existence, accepting the organisms that depend on it, giving it the support to which, due to its beneficial aims, it has become deserving, as it is totally separated from any political tendency.

Bearing in mind that the R.D. of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers dated 26 February 1920, is still in force, by which it is not possible to create groups of exploradores or Scouts nor to make affiliated use of suits or uniforms equal or similar to those that have been used since their formation by the Exploradores de España.

By virtue of the powers vested in me, I hereby resolve:

First.- The decrees of the Government of the Generalitat of Catalonia of August 9th and September 18th, by which the Boy Scouts de Catalunya, Germanor de Guies Excursionistes, Germanor de Minyons de Muntanya and Germanor de Noies Guies, respectively were placed under the patronage of the Generalitat, are null and void and without any effect whatsoever.

Second.- In compliance with the provisions on the matter it is well understood, for these purposes, that there is no other organization of this nature than that which bears the already recognized name of the Exploradores de España.

Barcelona, 6 November 1934.

Accidental President designated by the Military Governmental Authority of the 4th Division.

Francisco Jiménez Arenas.[97]

Civil War

Most of the Exploradores de España groups suspended or limited their activities during the Civil War (1936-1939), as many rovers (older scouts) and instructors were deployed.[98] At the outbreak of the uprising, on 18 July 1936, many groups were in summer camp. Although almost all managed to return to their towns without major difficulties, the exploradores of the Zaragoza Troop who were in the Odesa National Park were evacuated to Barcelona where they found refuge and were placed under the custody of the Boy Scouts de Catalunya. In June 1937, following a number of efforts by the Red Cross, they managed to pass through France via Hendaye-Irun and were able to return to their homes.[99][100]

Early into the war, there were practically no official manifestations or dispositions on either side, neither in favor nor against the exploradores. The Exploradores de España, in accordance with the principles of their statutes, remained distanced from any political ideology, and wherever the local council considered it possible, offered their collaboration to the legally established authority to perform services of a humanitarian nature.[101]

However, in the areas known as "nationals", there was an apparent tendency from other European countries to abolish scouting or, failing that, to transform it into something more in line with the totalitarian postulates of the regime. On 28 July 1936 the Correo de Mallorca issued a statement on its front page:

A falangist children's section among the children of the families of Mallorca is being organized in order to train them to form the future Guides or Chiefs of the Patrols that, like Balillas and with the name of Exploradores de Falange, will be organized in Baleares and the Peninsula.[102]

It was towards the end of the war when a certain attitude of the rebel side was openly evident, a bad omen for the future of the scouting institution. The exploradores were dissolved in some territories by the military authorities, for example in Galicia, on the grounds of being "a modern institution of exotic origin" and for "subtracting the position of Spanish youth in other Falange Youth Organizations such as cadetes, flechas o pelayos" as quoted by the captain general of Galicia, Germán Gil y Yuste in his decree of dissolution, dated 25 March 1938,[103] and published in various press media of the time.[104][105][106][107]

At the end of the war in April 1939, the scout association found itself in a complicated situation and without information of what had become of the local councils. Many rovers and instructors had been killed in the fighting, others were in exile or simply considered missing.[108] However, there was a small nucleus in Madrid that kept their faith in scouting, but they were cautious in their attempt to reorganize, partly because of the hostile attitude of some leading cadres of the public administration.[109]

But there were also sectors that accepted the new regime and that expressed their intention to abide by any administrative resolution that meant the total annihilation of the association, as is evident from the correspondence coming from the International Scout Bureau in London which stated:

Should it come to pass [that] Scouting were to be absorbed into the (single) National Movement of Youth, we are convinced [that] all the Exploradores de España will accept the decision and will do their best to fulfill their duties with loyalty according to the Promise they made as scouts.[110]

and the response of Fernando Molina-Niñirola Sánchez (Tigre en Acecho), then commissioner of the Murcia Group:

If official Spanish scouting must disappear, we will always be reverent towards our Caudillo and the national authorities, following the patriotic principles that we can never set aside.[110]

Víctor José Jiménez y Malo de Molina was one of the supporters of initiating activities aimed to the reorganization of the Exploradores de España by the end of the Civil War. He tried unsuccessfully to safeguard the survival of the exploradores in a last attempt to create Exploradores de FET y de las JONS (Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS), in a letter accompanying a broad project sent to Raimundo Fernández-Cuesta, on 26 May 1938:

This is not the work of a single brain, but the constant study of the greatest pedagogues in Spain and abroad, because the basis that it supports, although it comes from scouting, is the same that supports the Hitlerjugend and the Opera Nazionale Balilla and is adapted to the Spanish character and our childhood...[111][112]

The proposal was rejected. Following in the footsteps of the German and Italian scout associations, the Exploradores de España were on their way to their end. José María Gutiérrez del Castillo, national secretary for the Youth Organization of FET-JONS, in a letter to Fernández-Cuesta on 17 June 1938, was in favor of eradicating the Scouts and reserving exclusively the "Youth Organizations" of FET-JONS (which would later be reconverted into the "Frente de Juventudes"), as the only channel of participation for Spanish youth.[112] José María Gutiérrez del Castillo (known as Chemari in his native Valladolid) was the creator in 1937 of the OOJJ, turning all his efforts to eliminate the boy scouts and any other direct competition to his purpose, to unify them into a single entity: La Falange. He was the architect of a forced absorption, turning Valladolid into the nerve center of such a strategy, where any independent initiative to the single youth movement became impossible.[113]

The proposal was rejected. Following in the footsteps of the German and Italian scout associations, the Spanish scouts were on their way to their end. José María Gutiérrez del Castillo, national secretary for the Youth Organization of FET-JONS, in a letter to Fernández-Cuesta on 17 June 1938, was in favor of eradicating the Scouts and reserving exclusively the "Youth Organizations" of FET-JONS (which would later be reconverted into the "Frente de Juventudes"), as the only channel of participation for Spanish youth.[112] José María Gutiérrez del Castillo (known as Chemari in his native Valladolid) was the creator in 1937 of the OOJJ, turning all his efforts to eliminate the boy scouts and any other direct competition to his purpose, to unify them into a single entity: La Falange. He was the creator of a "forced" absorption, turning Valladolid into the nerve center of such a strategy, where any independent initiative to the single youth movement became impossible.[113]

Fernando Molina-Niñirola Sánchez

Fernando Molina-Niñirola Sánchez (3 October 1908 – 20 July 1990) joined the Murcia Troop on 9 May 1921. A doctor by profession, he was a member of the Catholic Association of Propagandists.[114] He kept up the Espuña Camp every summer during the Civil War. He was rewarded with the Silver Wolf on 31 December 1938.[115][116] Although he maintained his relationship with his fellow exploradores, he would not return to active scouting. However, Fernando Molina-Niñirola kept in custody all the scouting documentary heritage in the region, from the Agrupación Local de Murcia (1915-1939), the Consejo Provincial de los Exploradores de Murcia (from 1917), the clandestinity period and its successors until about 1980, documentation that was donated by his relatives to the General Archive of the Region of Murcia in 2013.[117]

Suspension of activities

On 28 February 1940 Teodoro Iradier died.[118] On 22 April 1940 the Orden Circular number 9 of the Ministerio de la Gobernación, sent to all civil governors, provided:

Considering that (..) the purposes assigned to the Exploradores de España in Article 1.º of its Statutes are embedded, although with deviations in its orientation, in the Organizaciones Juveniles de FET y de las JONS that dedicate their activities to the formation and exaltation of the unity of the national spirit, through moral, physical, patriotic and pre-military education, based on the National Syndicalist principles; the logical conclusion arises that, at the present time, not only it lacks a reason to exist, but it is incompatible with these postulates, an Association that, as the Exploradores de España, applies to the fulfillment of its purposes the principles, methods and procedures of universal scouting, in relation to and under the dependence of organizations of international character. Consequently, the Exploradores de España currently lacks personality. I hereby inform your Excellency for your knowledge and consequent effects. Madrid, 22 April 1940.[119]

This order was appealed by the institution, without success, since the youth policy of the regime was entrusted exclusively to FET-JONS. The Exploradores de España were banned,[120] and consequently their premises and assets were seized. The general commissariat of the association, initially composed of Juan Antonio Dimas (who resigned in 1940), Francisco Medina, Isidoro de la Cierva (who died in 1939) and Víctor José Jiménez y Malo de Molina, functioned intermittently in Madrid.[109]

Subsequently, some nuclei emerged again that would open another chapter in the history of Spanish scouting during the clandestinity period. Former scouts and leaders kept the spirit of the movement alive, hoping to return to an authorized activity.[121] Old files and all kinds of symbols of the association hidden by former members were used at meals and private meetings to prevent them from being seized.[98] Francisco Medina Ample, last known general commissioner of the Association and successor of Dimas,[122] later received an official notice from the Ministry of the Interior "reminding him that the Asociación de Exploradores de España was still in suspension of activities."[109]

Symbology

Iradier chose the wheel and five-pointed star as its institutional emblem, in his own words "like the polar star that guides sailors, like the star of the east that guided the Magi to the birthplace of the Redeemer, and like the emblem of the great explorers and of the General Staffs of the Armies".[123] As a motto "Siempre Adelante" (English: Always Onward), since "the explorador sees a future to which he directs his efforts, straight, sure, without hesitation"; the Exploradores de Zaragoza released a publication whose title coincided with the same motto in 1924.[124] The ensign for the association was the national flag with a diagonal green stripe, "Symbol of Nature and Hope". Each troop added the coat of arms of the locality in the center with the inscription "Los Exploradores de España" in the upper stripe next to the badge of the association. In 1921, a Royal Decree granted military honors to the flag of Spain carried by the troops of the Exploradores de España.[125] For his part, Dimas said of the national ensign that "it carries in itself light of sun, blood and hope".[126]

Promise and Code of the Explorador

Promise of the Explorador

On my honor, I promise to do what is in my power, to:[127][128]

- To fulfill my duties to God and to the Head of State.

- To love my homeland, to be useful to it at all times and to respect its laws.

- To obey the Scout Code.

Code of the Explorador

The code—unlike its English version which had ten points—had twelve points:[129][130][128]

- The explorador is honest and his word deserves absolute trust.

- The explorador is not afraid of ridicule when it comes to noble deeds.

- The explorador is obedient; he is disciplined; he is loyal.

- The explorador has initiative; but he is also aware of the responsibility of his actions.

- The explorador is tolerant; he is courteous; he is helpful.

- The explorador is a friend to all, and considers other exploradores as his brothers without distinction of class.

- The explorador is brave and eager to be useful and to help the weak.

- The explorador does a good deed every day, however modest it may be.

- The explorador loves animals, trees and plants.

- The explorador is clean and cheerful.

- The explorador is thrifty, he is hardworking, he is tenacious, he is persevering.

- The explorador's greatest honor is to be one, for this title implies loftiness of vision and nobility of sentiment.

Hymn of Exploradores de España

Early 1913, the "Himno de los Exploradores" was composed with lyrics by Mariano Benavente Martínez, father of two exploradores from Madrid and brother of the playwright Jacinto Benavente, member of the Real Academia Española.[131] The musical score was composed by another father of exploradores from Madrid, the musician Melecio Brull y Ayerra.[132]

Lyrics

Original full version of the hymn of the explorador:[133]

- Seréis para ser buenos, mejores cada día,

- con este faro y guía: cumplir nuestro deber.

- Caricia y besos de auras y brisas,

- como sonrisas de amanecer.

- Primero aurora y después lumbrera,

- nuestra bandera tiene que ser.

- Gloriosa madre, Patria querida,

- más que a mi vida, he de guardarte.

- Tu santo nombre, será mi ensueño,

- y aunque pequeñó, sabré yo honrarte.

- El grande o el pequeño, la cumbre o el abismo,

- será todo lo mismo, mirado con fervor.

- Las llagas del leproso que son para el cristiano,

- si en él mira a un hermano luz, caridad y amor.

- Caricia y besos de auras y brisas,

- como sonrisas de amanecer.

- Primero aurora y después lumbrera,

- nuestra bandera tiene que ser.

- Gloriosa madre, Patria querida,

- más que a mi vida, he de guardarte.

- Tu santo nombre, será mi ensueño,

- y aunque pequeñó, sabré yo honrarte.

- Siempre adelante, siempre adelante

- cumpliendo alegres nuestro deber.

- Siempre avanzando, nada hay distante,

- que es humillante retroceder.

- Unid las almas, juntas las vidas,

- al fuego santo de un solo hogar.

- Las gotas de agua, si van unidas,

- formando ríos llegan al mar, llegan al mar.

- Siempre adelante, siempre adelante,

- de abismo a cumbre quiero subir.

- Llevando a España, siempre triunfante,

- por los senderos del porvenir.

- Cual los aceros de las espadas,

- del yunque al fuego templadas son.

- En las empresas más arriesgadas,

- pruebe su temple en mi corazón.

- La rama es antes brote, primero el hombre es niño.

- Miradnos con cariño, que es nuestro el porvenir.

- El pobre y el pequeño, el niño y el anciano,

- serán como un hermano de todo explorador.

- Y con semblante alegre, sabré por mi camino,

- sembrar algo divino luz, caridad y amor.

- Si soy pequeño, querida España,

- para una hazaña digna de ti.

- cuando al amarte sé comprenderte

- enaltecerte ya conseguí.

- ¡Glorioso faro!, ¡Santa Bandera!

- Mi compañera hasta la muerte.

- Que en sangriento combate rudo

- será tu escudo, mi pecho fuerte.

Other relevant figures of the institution

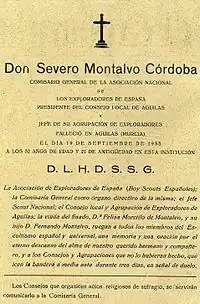

Severo Montalvo Córdoba

Severo Montalvo Córdoba (1883-1935), chief telegrapher by profession. Known in the scouting circles as Lobo Rojo, he was a brilliant troop leader in Águilas (Murcia),[134] president of the group and recognized as the best scouting technician of his time. During the institutional decline between, 1914 and 1919, he was the critical voice of the association, and gave as reasons the resignation of Iradier,[135] which added to the lack of enthusiasm of the first benefactors and the weariness of the public who judged by what they saw. Together with Juan Antonio Dimas they translated into Spanish the scouting work The Patrol System by Roland Philipps.[136] He was elected in 1933 one of the five general commissioners of the association, as secretary-administrator. He committed suicide one morning on 19 September 1935,[137] as quoted by José María López Lacárcel, during an allegedly long period of depression and emotional problems; after his death he was replaced by Isidoro de la Cierva. The tragedy was much lamented, as he was "a much loved character in the region", reason for 10 000 people to pay him the last farewell, among which were the troops of Albox, Murcia, and Cartagena.[138] Severo Montalvo has a street dedicated in the municipality of Águilas for his extensive career in favor of local youth.[139]

Mariano de la Paz Gómez y Rodríguez

Mariano de la Paz Gómez y Rodríguez, doctor in Law and in Philosophy and Literature.[140] He joined the Exploradores de España in 1914 and was recorded as commander of the Linares Troop in 1919. He was local commissioner of Linares and provincial of Córdoba, and president of the Federación de Exploradores del Norte Andaluz. He was very fond of natural sciences and archaeology, he was also taxidermist and writer, among his works are La Propiedad privada en las guerras marítimas (T. Fortanet, 1905) and Estudio histórico sobre la religión del imperio de los Incas (T. Fortanet, 1907). He received the "Lobo de Plata" on 1 July 1934,[115] supported by the councils of Linares, Águilas, Centenillo, Málaga, Córdoba and Madrid.[141] He had a habit of inviting nearby troops of exploradores to his spacious estate.[142] The "Museo de Ciencias Naturales" that bears his name remains in Linares.[143]

Enrique del Castillo y Pez

Enrique del Castillo y Pez (b. 21 March 1876), commander of the Carabineros.[144] Chief of the Malaga Troop and instructor of Fuengirola and Marbella. Ex-combatant of the Cuban War, he held numerous military decorations such as the First Class Cross of Military Merit with white badge awarded on 28 November 1918, and the Gold Medal of Scouting Merit, awarded for his valuable work as an instructor.[145][146] He received the "Lobo de Plata" in 1934.[115] In 1938. he became available to the Military Governor of Malaga, coming from the Malaga Telephone Exchange, being declared fit for bureaucratic services after being discharged from the Malaga Hospital.[147] He has two streets dedicated to his name in Malaga,[148] as an adopted son of that city, and Marbella.[149]

Javier Casares Bescansa

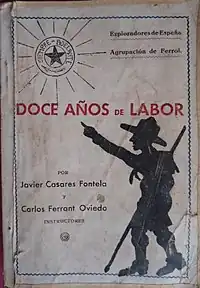

Javier Casares Bescansa (1875-1964), medical lieutenant colonel of the Navy.[150] Chief of the El Ferrol Troop in 1922 and local commissioner in 1935. Javier Casares was the creator of Yodovitamín Casares syrup, a very popular immune system booster in the mid-1920s.[151] A promoter of the ferrolan Semana Santa, he was a member of Acción Católica,[152] and member of the Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas in Galicia.[153] He received the "Lobo de Plata" in 1934.[115] He combined his medical and research endeavours with the Christian values of service to others, love of nature and sporting activities. His three sons were all exploreradores; one of them, Javier Casares Fontela, wrote and published in 1932 his scouting experience in a memoir.[154]

Ángel Rebollo Vizcaíno

Ángel Rebollo Vizcaíno (d. 16 June 1949), tailor by profession, joined the institution in 1913 and later became an instructor. He was listed as troop chief and local commissioner of La Coruña from 1925 to October 1936. In 1935, he was part of the board of directors of the cycling group Velo-Club Coruñés.[155] He received the "Lobo de Plata" in 1934.[156][115] He was one of the candidates of the Grupo Independiente Coruñesista in the first municipal elections of Franco's regime (21 November 1948), candidacy that was made public on 16 November 1948.[157]

Francisco Medina Ample

Francisco Medina Ample, teacher and director of the National Orphanage of El Pardo, Madrid (ONP).[158] One of the first five general commissioners, as delegate of the lobatos and coordinator for groups of schools and other entities, in 1933.[159] Francisco Medina signed the communiqués with Juan Antonio Dimas at the end of the civil war, as members of the general commissariat, seeking recognition and administrative permission to continue with the activities of the exploradores, but never received the desired response. He took charge of the Exploradores de Expaña after the resignation of Juan Antonio Dimas, at the end of 1940.[160]

In 1951, he was a member of the national commission for the reorganization of Spanish Scouting, together with Enrique Genovés Guillén and Víctor José Jiménez y Malo de Molina, all three representing the Exploradores de España.[161] He was the last active commissioner of the original constitution, and continued in his position as such on the organizing commission to attempt the legalization of the Asociación de Scouts de España in March 1962.[162]

In 1969, he entered the Order of Beneficence receiving honors with white badge and second class Cross category.[163] A regular contributor to the magazine Escuela Española, he was the author of La educación en régimen de internado.[164]

Gallery

Exploradores of Ávila in their first public exhibition on the occasion of the promise (1913)

Exploradores of Ávila in their first public exhibition on the occasion of the promise (1913) Exploradores de España, Ceuta Troop (1915)

Exploradores de España, Ceuta Troop (1915) Exploradores de Mar de Cartagena (1916)

Exploradores de Mar de Cartagena (1916) Alfonso of Bourbon and Battenberg, Prince of Asturias (1918)

Alfonso of Bourbon and Battenberg, Prince of Asturias (1918)_-_Fondo_Car-Kutxa_Fototeka.jpg.webp) Exploradores de España, visit to San Sebastián (1920)

Exploradores de España, visit to San Sebastián (1920) Exploradores de España, Tordesillas Group (1924)

Exploradores de España, Tordesillas Group (1924) Exploradores de España, Minas de Riotinto Group (1925)

Exploradores de España, Minas de Riotinto Group (1925) Exploradores de España, Melilla Group in Río de Oro (1929)

Exploradores de España, Melilla Group in Río de Oro (1929) Badge of the Exploradores de España (1922-1931) for the cuatro bollos hat, typical headgear for the boy scouts.

Badge of the Exploradores de España (1922-1931) for the cuatro bollos hat, typical headgear for the boy scouts. Scout badge without the fleur-de-lis, used during the 2nd Republic. It was Robert Baden-Powell's idea to add the scout salute.

Scout badge without the fleur-de-lis, used during the 2nd Republic. It was Robert Baden-Powell's idea to add the scout salute. Flag of the Exploradores de Cádiz, currently under custody of the Cádiz Kanguro Patrol

Flag of the Exploradores de Cádiz, currently under custody of the Cádiz Kanguro Patrol

See also

References

- ↑ Ruiz Rodrigo, Cándido. Educación social: Viejos usos y nuevos retos. Universitat de València. p. 35. ISBN 8437057833.

- ↑ "Vol 7". Gran enciclopedia Larousse en veinte volúmenes. Larousse. 1967. p. 371. ISBN 8432020605.

- ↑ Scouting Around the World, Facts and figures on the World Scout Movement. Geneva, Switzerland: World Organization of the Scout Movement. 1990. pp. 111–112. ISBN 2-88052-001-0.

- ↑ Casals, Xavier (2005). Franco y los Borbones: la corona de España y sus pretendientes. Planeta. p. 29. ISBN 8408063138.

- ↑ El Movimiento Laico y Progresista: la revolución sin pasamontañas: formación de dirigentes. Fundació Ferrer i Guàrdia. 2006. pp. 19–20. ISBN 8487064590. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ↑ Gil Pecharromán, Julio (2003). José Antonio Primo de Rivera: retrato de un visionario. Temas de Hoy. Temas de Hoy. p. 45. ISBN 8484602737.

- 1 2 Gonzàlez Agàpito, Josep (2002). Tradició i renovació pedagògica, 1898-1939: història de l'educació : Catalunya, Illes Balears, País Valencià (in Catalan). L'Abadia de Montserrat. pp. 618–619. ISBN 8484153002.

- 1 2 3 Quintana Cabanas, José María (1991). Iniciativas sociales en educación informal. Madrid: Ediciones Rialp. p. 144. ISBN 8432127000. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ↑ Vallès, Edmon (1975). Història gràfica de la Catalunya contemporània, 1888/1931: De Solidaritat Catalana a la Mancomunitat, 1908-1916 (in Catalan). Edicions 62. p. 294. ISBN 8429710256.

- ↑ de Borja i Solé, María (1984). El juego como actividad educativa: instruir deleitando. Edicions Universitat Barcelona. p. 88. ISBN 8475281117.

- ↑ "Constitución Comité Provincial de Boy-Scouts de Barcelona". La Vanguardia. 7 November 1912. p. 4. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ↑ Tusquets, Joan (May 1986 – December 1987). "El nomadisme pedagògic a Catalunya". Full Informatiu de la Societat Catalana d'Historia de l'Educacio dels Països de Llengua Catalana (in Catalan). Institut d'Estudis Catalans. p. 45.

- ↑ Tusquets, Joan (1982). El nomadisme pedagògic a Catalunya (in Catalan). Vol. 38. Reial Acadèmia de Bones Lletres. pp. 207–223. ISSN 2339-9856.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Ferret, Antoni (1968). Compendi d'història de Catalunya (segle xx) (in Catalan). Editorial Bruguera. p. 42.

- ↑ Navarro, Emilio (1916). Album Histórico de las Sociedades Deportivas de Barcelona. Spain: Imprenta José Ortega. pp. 185–188.

- 1 2 Aracil Martí, Rafael (2000). Ensenyament, cultura, justícia (in Catalan). Edicions Universitat Barcelona. p. 50. ISBN 8483384078.

- ↑ Serra, Antoni (1968). Història de l'Escoltisme Català. Editorial Bruguera. p. 11.

- ↑ Gabarró, Marcel (1999). L'escoltisme a Catalunya (1912-1939) (in Catalan). Ajuntament de Barcelona. p. 117.

- ↑ de Borja i Solé, Maria (1984). El juego como actividad educativa: instruir deleitando (in Spanish). Edicions Universitat Barcelona. p. 89. ISBN 8475281117.

- ↑ El Fons de l'Escoltisme Català de l'Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya (in Catalan). Spain: Generalitat de Catalunya: Departament de Cultura. 2014. p. 13.

- ↑ del Pozo Andrés, María del Mar (2000). Currículum e Identidad Nacional: Regeneracionismos, Nacionalismos y Escuela Pública, 1890-1939. Biblioteca Nueva. p. 257. ISBN 8470307932.

- ↑ "Vol. 24-26". Investigaciones históricas. Universidad de Valladolid. Departamento de Historia Contemporánea, Secretariado de Publicaciones. 2004. p. 262.

- ↑ Varela-Lago, Ana Maria (2008). Conquerors, Immigrants, Exiles: The Spanish Diaspora in the United States (1848-1948). p. 111. ISBN 978-0549423553.

- ↑ Ruiz Rodrigo, Cándido; Palacio Lis, Irene (1999). Higienismo, educación ambiental y previsión escolar. Universitat de València. p. 151. ISBN 8437039304.

- ↑ Cruz, J. Ignacio (1 July 1993). "Escultismo, masonería y antimasonería: los casos de Francia y España". La masonería española entre Europa y América: VI Symposium Internacional de Historia de la Masonería Española (in Spanish). Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón, Departamento de Educación y Cultura. p. 533. ISBN 8477535361.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 31.

- ↑ La fiesta de los Exploradores de España. 28 April 2013. ISSN 2444-1325. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 157.

- ↑ Vallès, Edmond (1975). Història gràfica de la Catalunya contemporània, 1888/1931: De solidaritat catalana a la mancomunitat (in Catalan). Edicions 62. p. 294. ISBN 8429710256.

- ↑ El Explorador Magazine, n.º 21, June 1914.

- ↑ Gaceta de Madrid.

- ↑ Boletín de la Revista general de legislación y jurisprudencia, La Revista de Legislación. Vol. 154. 1914. p. 161.

- ↑ Armada Muñoz, Francisco José (2009). El escultismo andaluz: cien años de educación para la buena ciudadanía. Scouts de Andalucía. p. 6. ISBN 978-8461340125.

- ↑ El Explorador (in Spanish). Vol. 28 de enero. 1915. p. 15.

- ↑ Buendía, Fabián (1984). Los Exploradores de España. Retazos de su historia. Madrid: Tutor. pp. 63 y 88.

- ↑ Cerdà, Mateu (1998). L'escoltisme a Mallorca (1907-1995) (in Catalan). Barcelona: Biblioteca Abat Oliva. p. 102. ISBN 8484153002.

- ↑ González-Agàpito, Josep (2002). Tradició i renovació pedagògica, 1898-1939: història de l'educació : Catalunya, Illes Balears, País Valencià (in Catalan). L'Abadia de Montserrat. p. 341. ISBN 8484153002.

- ↑ Cerdà, Mateu (1999). L'Escoltisme a Mallorca, 1907-1995 (in Catalan). L'Abadia de Montserrat. p. 115. ISBN 8484150461.

- ↑ Genovés Guillén, Enrique (1984). Cronología del Movimiento Scout. p. 17.

- ↑ Vida Marítima. 1916.

- ↑ "Vol. 2". La Edad de Plata de la cultura española. Espasa Calpe. 1993. p. 821. ISBN 8423948005.

- ↑ Jobit, Pierre (1965). L'Église d'Espagne à l'heure du Concile (in French). Éditions Spes. p. 61.

- ↑ Armada Muñoz, Francisco José (2009). El escultismo andaluz: cien años de educación para la buena ciudadanía (in Spanish). Scouts de Andalucía. p. 8. ISBN 978-8461340125.

- ↑ Tratado elemental de derecho administrativo, principios y legislacion española: Organización administrativo. Imprenta clásica española. 1921. p. 223. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Ferret, Antoni (1968). Compendi d'història de Catalunya (segle xx) (in Catalan). Editorial Bruguera. p. 43.

- 1 2 Pastor Pradillo, José Luis (1997). El espacio profesional de la educación física en España: Génesis y formación (1883-1961). Universidad de Alcalá, Servicio de Publicaciones. p. 297. ISBN 8481382140.

- ↑ González Calleja, Eduardo; del Rey Reguillo, Fernando (1995). La defensa armada contra la revolución: una historia de las guardias cívicas en la España del siglo XX. CSIC Press. p. 190. ISBN 8400075528.

- ↑ Galí, Alexandre (1983). Història de les institucions i del moviment cultural a Catalunya (1900-1936) (in Catalan). Barcelona: Fundació Alexandre Galí. p. 147. ISBN 8440047851.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España. ASDE. p. 84.

- ↑ El Explorador Magazine, n° 229, April 1928.

- 1 2 Amorós, Andrés (1991). Luces de candilejas: los espectáculos en España (1898-1939). Espasa Calpe. pp. 250. ISBN 842391996X.

- ↑ "Historia de Minas de Riotinto". Excmo. Ayuntamiento de Minas de RioTinto. 23 December 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ↑ San Sebastián. Una fiesta de los exploradores. Vol. XXXII. Barcelona: Montaner y Simón. 28 July 1913. p. 498. ISSN 1889-853X.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ La semana gráfica. Madrid: Prensa Española. 12 September 1915. p. 41. ISSN 0006-4572.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Cruz Orozco, José Ignacio (1995). Escultismo, educación y tiempo libre. Historia del Asociacionismo Scout en Valencia. Valencia: Instituto Valenciano de la Juventud. p. 48.

- ↑ González-Agàpito, Josep (2002). Tradició i renovació pedagògica, 1898-1939: història de l'educació : Catalunya, Illes Balears, País Valencià (in Catalan). L'Abadia de Montserrat. p. 343. ISBN 8484153002.

- ↑ "Juego Limpio." El Explorador, issue 53, 1917 (Madrid).

- ↑ Unamuno, M. «Boyscouts y footballistas» (31 January 1921) Boletín de la Institución Libre de Enseñanza, year XLV, nº 730: pp. 14-15.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 55.

- ↑ Genovés Guillén, Enrique (1998). El Lobo de Plata - Notas sobre su historia y su Cuadro de Honor. Dep. Legal M-26154. Madrid. p. 13.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ La Patrulla. 1932.

- ↑ Asociación de Guías de España, Entrevista a Marita, nuestra fundadora, circular 3, 1977-8, p. 6.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 71.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 139.

- ↑ Vendrell Guarro, Esteve; Ayer, Juan Carlos; Vendrell, E. (1999). Dinàmica de grups i psicologia dels grups (in Catalan). Edicions Universitat Barcelona. p. 73. ISBN 8483380730. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ "Del Jamborée internacional - Los exploradores polacos". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 3 September 1929. p. 8. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ "Marruecos - Visita de inspección : Regreso de los exploradores - Sobre la muerte de un explorador tangerino : Descubrimiento". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 6 September 1929. p. 19. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 93.

- ↑ Armada Muñoz, Francisco José (2009). El escultismo andaluz: cien años de educación para la buena ciudadanía (in Spanish). Scouts de Andalucía. p. 62. ISBN 978-8461340125.

- ↑ Barba, C. (1994). Organizaciones infantiles y juveniles de tiempo libre. Narcea Ediciones. p. 98. ISBN 842771064X.

- ↑ Gómez Díaz, Donato; Martínez López, José Miguel (2001). El deporte en Almería, 1880-1939. Una historia sobre el ocio y la formación de la identidad provincial (in Spanish). Universidad de Almería. p. 272. ISBN 8482403419.

- ↑ Genovés Guillén, Enrique (1998). El Lobo de Plata - Notas sobre su historia y su Cuadro de Honor (in Spanish). Dep. Legal M-26154. Madrid. pp. 14–15.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ La Patrulla (in Spanish). 1933.

- ↑ La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 18 April 1931. p. 16.

- ↑ Ruiz, Jacome (1936). Legislación ordenada y comentada de la República española: abril-julio 1931 (in Spanish). Bergua. p. 152.

- ↑ Escultismo, boletín oficial de la Federación Regional Valenciana de Exploradores (in Spanish). April 1933.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 113.

- ↑ Alcoba López, Antonio (2002). Auge y ocaso de El Frente de Juventudes. San Martín. p. 34. ISBN 8471402211.

- ↑ Armada Muñoz, Francisco José (2009). El escultismo andaluz: cien años de educación para la buena ciudadanía (in Spanish). Scouts de Andalucía. p. 10. ISBN 978-8461340125.

- ↑ Álvarez Rey, Leandro (2009). Los Diputados por Andalucía de la Segunda República, 1931-1939: diccionario biográfico. F-M (in Spanish). Granada: Centro de Estudios Andaluces. p. 369. ISBN 978-8493785505.

- ↑ Legislación y disposiciones de la administración central: Comprende las leyes, códigos, decretos, reglamentos, instrucciones, órdenes, circulares y resoluciones de interés general (in Spanish). Vol. 2. 1936. p. 294.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Cucurull, Félix (1975). Panoràmica del nacionalisme català: Del 1914 al 1931 (in Catalan). Edicions catalanes de París. p. 65. ISBN 2850410217.

- ↑ Cucurull, Félix (1984). Catalunya, republicana i autònoma, 1931-1936 (in Catalan). Edicions de la Magrana. p. 77. ISBN 8474101549.

- ↑ Gabriel Sirvent, Pere (1990). El ideario social de Joan Peiró (in Spanish). Anthropos Editorial. p. 33. ISSN 0211-5611.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ "Protesta del jefe de exploradores Carlos de Cifuentes sobre los disturbios del 28 de abril". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 30 April 1930. p. 6. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ↑ Solà, P. (1993). Associacionisme i condició juvenil: La joventut a Catalunya al segle XX (in Catalan). Barcelona: Diputación de Barcelona. p. 325.

- ↑ Els Fons de l'escoltisme català de l'Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya (PDF) (in Spanish). Barcelona. 2014. p. 14. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "ABC MADRID 09-03-1933 página 32 - Archivo ABC". abc. 2019-08-05. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- 1 2 Gabarró, Marcel (1999). L'escoltisme a Catalunya (1912-1939) (in Catalan). Ajuntament de Barcelona. pp. 128–130.

- ↑ "75 anys d'escoltisme català." Butlletí de l'Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya, n.º 6, October 2003 (in Catalonian).

- ↑ de Riquer, Borja; Carbonell i Curell, Anna; Abad i Carilla, Montserrat (2008). Història, política, societat i cultura dels països catalans: De la gran esperança a la gran ensulsiada 1930-1939 (in Catalan). Enciclopèdia Catalana. p. 205. ISBN 978-8441224834.

- ↑ "El Explorador" (in Spanish). No. 269. October 1934. p. 9.

- ↑ "El Explorador" (in Spanish). No. 270. November 1934. p. 28.

- ↑ Balcells, Albert (1993). L'escoltisme català (1911-1978) (in Catalan). Barcanova. p. 55. ISBN 8475339204.

- ↑ de Riquer, Borja; Carbonell i Curell, Montserrat; Abad i Carilla, Anna (2008). Història, política, societat i cultura dels països catalans: De la gran esperanca a la gran ensulsiada 1930-1939 (in Catalan). Enciclopèdia Catalana. pp. 205–8. ISBN 978-8441224834.

- ↑ Cómo los hombres de la Generalidad volvieron a encontrarse donde se habían dicho adiós (in Spanish). 26 February 1936. pp. 10–13. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ "Orden". Boletín Oficial de la Generalidad de Cataluña. No. 311. 7 November 1934. pp. 783–84.

- 1 2 Alaminos López, Antonio (12 August 2014). "El origen de los Exploradores". Ideal. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ↑ Millán, Jesús Alonso, La guerra total en España (1936-1939), 2013, p. 175.

- ↑ Gaceta de Tenerife: Diario católico de información, number 8918, Tuesday 8 June 1937.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 151.

- ↑ Massot i Muntaner, Josep (1987). El desembarcament de Bayo a Mallorca: agost-setembre de 1936 (in Catalan). L'Abadia de Montserrat. p. 144. ISBN 8472028356.

- ↑ Fernández, Carlos. "La guerra civil en Galicia." La Voz de Galicia, 1988, p. 297.

- ↑ Diario de Córdoba, Friday April 8, 1938.

- ↑ El Progreso (Lugo), Sunday March 27, 1938.

- ↑ El Pensamiento Alavés, Wednesday April 6, 1938.

- ↑ Diario Palentino, Saturday April 9, 1938.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España. ASDE. p. 160.

- 1 2 3 López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 163.

- 1 2 Pagès i Blanch, Pelai (2004). Franquisme i repressió: La repressió franquista als Països Catalans (in Catalan). Universitat de València. p. 198. ISBN 8437059240.

- ↑ Pérez, Adaucto. OOJJ: las Organizaciones Juveniles de la FET.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 164.

- 1 2 Espeso González, Juan Antonio (2012). Ayuntamiento de Valladolid (ed.). Hay huellas scouts por Valladolid (in Spanish). Valladolid: Imprenta Municipal de Valladolid. pp. 151–3. ISBN 9788496864771.

- ↑ Pérez Crespo, Antonio (2013). Historia del Centro de Murcia de la Asociación Católica de Propagandistas (ACdP). De 1926 a 2011 (in Spanish). Fundación Univ. San Pablo. p. 710. ISBN 978-8415382737.

- 1 2 3 4 5 El Kanguro de Cádiz (1980), La Saga del Kanguro: medio siglo de una patrulla scout, Don Bosco (ed.), ISBN 8423614506 p. 187.

- ↑ Genovés Guillén, Enrique (1998). El Lobo de Plata - Notas sobre su historia y su Cuadro de Honor (in Spanish). Dep. Legal M-26154. Madrid. pp. 24–5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "La familia Molina-Niñirola dona el archivo de los Boys Scouts desde su fundación en Murcia en 1915". Europa Press. Murcia. 28 August 2013.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 162.

- ↑ Investigaciones históricas (in Spanish). Vol. 24-26 p. 262.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Vallory, Eduard (2012). World Scouting: Educating for Global Citizenship. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 27. ISBN 978-1137012067.

- ↑ Wilson, John S. (1959). Scouting Round the World. London: Blandford Press Ltd. p. 160.

- ↑ "En recuerdo de Juan Antonio Dimas. La Verdad". www.laverdad.es. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España. ASDE. p. 38.

- ↑ Fernández Clemente, Eloy (1999). Gente de orden: La sociedad - Aragón durante la Dictadura de Primo de Rivera 1923-1930 (in Spanish). Caja de Ahorros y Monte de Piedad de Zaragoza, Aragón y Rioja. p. 316. ISBN 8488793618.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 168.

- ↑ Weekly magazine Ibérica, Year IV, Vol. VIII, 1917, p. 108.

- ↑ Dimas, Juan Antonio (Lobo Gris), La promesa y el código de los Exploradores de España: sencilla explicación que deben conocer los aspirantes a ingreso en esta Institución Nacional.

- 1 2 López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 35.

- ↑ Dimas, Juan Antonio, Comentarios a la Ley Scout. La Verdad (ed.), 1935.

- ↑ Los Doce Cuentos del Código de los Exploradores de España Boletín de la Sociedad Protectora de los Niños, 1913.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 40.

- ↑ Sagardia, Ángel (1972). Músicos vascos. Auñamendi. p. 102.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 41.

- ↑ Zavala, José María; Morodo, Juan José (1990). El último magnate: Alfonso Escámez, de botones a presidente (in Spanish). Pirámide. p. 64. ISBN 978-84-36805-37-6.

- ↑ Armada Muñoz, Francisco José (2009). El escultismo andaluz: cien años de educación para la buena ciudadanía (in Spanish). Scouts de Andalucía. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-8461340125.

- ↑ Un poco de historia (in Spanish). 1929.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ El Tiempo (Murcia), September 20, 1935

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 142.

- ↑ "Callejero de Águilas: calle de Severo Montalvo" (in Spanish).

- ↑ Gaceta de Madrid, issue 283, October 10, 1935, p. 576.

- ↑ Genovés Guillén, Enrique (1998). El Lobo de Plata - Notas sobre su historia y su Cuadro de Honor (in Spanish). Dep. Legal M-26154. Madrid. p. 20.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Sánchez-Berbel, Luis García (1993). El Centenillo: un pueblo andaluz y minero (in Spanish). Hijos de Muley-Rubio. p. 113. ISBN 8487567444.

- ↑ "Casa Museo de ciencias naturales D.Mariano de la Paz" (in Spanish).

- ↑ Gaceta de Madrid, Ministry of Interior of Spain, 1936, p. 1910.

- ↑ Gaceta de Madrid, Real Order of 22 December 1922, issue 287.

- ↑ Service record of Major Enrique del Castillo Pez, Archivo General Militar de Segovia, pp. 11 and 12.

- ↑ BOE, Boletín Oficial del Estado Press, 1938, p. 1998.

- ↑ "Callejero de Málaga: calle de Enrique del Castillo" (in Spanish).

- ↑ "Callejero de Marbella: calle de Enrique del Castillo" (in Spanish).

- ↑ Franco Castañón, Hermenegildo; Molina Franco, Lucas (2004). Por el camino de la revolución: la marina española, Alfonso XIII y la Segunda República. Neptuno Libros. p. 178. ISBN 8496016307.

- ↑ Gurriarán, Ricardo (2006). Ciencia e conciencia na universidade de Santiago, 1900-1940: do influxo institucionista e a JAE á depuración do profesorado (in Galician). Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. pp. 483, 103. ISBN 8497506448.

- ↑ Montero García, Feliciano La acción católica en la II República, Universidad de Alcalá, 2008, p. 136.

- ↑ Grandío Seoane, Emilio (1998). Los Orígenes de la Derecha Gallega: La C.E.D.A. en Galicia (1931-1936) (in Spanish). Ediciós do Castro. pp. 63, 77, 258. ISBN 8474929016.

- ↑ Casares Fontela, J. and Ferrant Oviedo, C., Doce años de labor, Exploradores de España, Agrupación de Ferrol, Imp. J. Montero, 1932.

- ↑ González Martín, Xerardo (2007). 120 anos de ciclismo gallego (in Galician). Galaxia. p. 303. ISBN 9788471541161. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ Genovés Guillén, Enrique (1998). El Lobo de Plata - Notas sobre su historia y su Cuadro de Honor (in Spanish). Dep. Legal M-26154. Madrid. p. 22.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Elecciones sin gas". La Voz de Galicia (in Spanish). 2003-05-10. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ↑ Escuela Española. 1970. p. 662.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 132.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. pp. 161–2.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2003), Así fuimos, así somos. Historia de Scouts de España. Exploradores de España, Federación de Asociaciones Scouts de España, ISBN 8493356506 p. 139.

- ↑ López Lacárcel, José María (2012). Huellas, cien años de Scouts de España (in Spanish). ASDE. p. 193.

- ↑ Resolución por la que se hace pública la concesión de ingreso en la Orden Civil de Beneficencia de don Francisco Medina Ample, Maestro nacional jubilado del Orfanato Nacional de El Pardo, vecino de Madrid, con distintivo blanco y categoría de Cruz de segunda clase (in Spanish). 18 April 1969. p. 5740. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ↑ Medina Ample, F., La educación en régimen de internado, In Servicio (ed.), Madrid, 1967.

Bibliography

- Borobio, Patricio (2017), Historia de un Campamento, ASDE (ed.), Garán Comunicaciones, ISBN 978-84-697-9449-4

- Armada Muñoz, Francisco José (2009), El escultismo andaluz: cien años de educación para la buena ciudadanía, Scouts de Andalusia, ISBN 8461340124

- Buendía Ruiz, Fabián (1984) Los exploradores de España: retazos de su historia, Madrid

- Cuyás Armengol, Arturo (1912), Los Exploradores de España: ¿Qué son? ¿Qué hacen?, Julián Palacios (ed.)

- Cuyás Armengol, Arturo (1913), Hace Falta un Muchacho, Giron Spanish Books Distributors, ISBN 9686769803

- Espeso González, Juan Antonio (2012), Hay huellas scouts por Valladolid, Ayuntamiento de Valladolid, Imprenta Municipal de Valladolid, ISBN 9788496864771

- Genovés Guillem, Enrique (1984), Cronología del Movimiento Scout, ISBN 8439811063

- Iradier y Herrero, Teodoro de (1912), Los Exploradores de España: (Boy Scouts Españoles) Estatutos y Reglamento interior provisionales

- Jiménez y Malo de Molina, Víctor José (1995), Mis cincuenta años de Escultismo, Madrid

- López Lacárcel, José María (1986), Los exploradores murcianos, 1913-1940, Ediciones Mediterráneo, ISBN 8485856562

- López Lacárcel, José María (2003), Así fuimos, así somos. Historia de Scouts de España-Exploradores de España, Federación de Asociaciones Scouts de España, ISBN 8493356506

- López Lacárcel, José María (2012), Huellas: Cien años de Scouts de España, Federación de Asociaciones de Scouts de España. Madrid.

- Portillo Strempel, Pablo (2015), Los exploradores malagueños 1913 a 1936, G.S. 125 San Estanislao (ed.), Malaga.

- Sánchez Bravo, Antonio y Dimas Hernández, Juan Antonio (1935), Exploradores de España: comentarios a la Ley Scout, La Verdad (ed.)

External links

- Motilla Salas, Xavier (October 2003). Universitat de les liles Balea (ed.). Estatutos y reglamento orgánico de la Asociación Nacional de los Exploradores de España y disposiciones oficiales que afectan a la misma (PDF). Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. ISSN 0212-0267.