Feuds in the United States deals with the phenomena of historic blood feuding in the United States. These feuds have been numerous and some became quite vicious. Often, a conflict which may have started out as a rivalry between two individuals or families became further escalated into a clan-wide feud or a range war, involving dozens—or even hundreds—of participants.[1] Below are listed some of the most notable blood feuds in United States history, most of which occurred in the Old West.

Early–Hasley

A family feud that took place immediately following the American Civil War, in Bell County, Texas from 1865 to 1869, the Early and Hasley families and their allies found themselves extending the ideological battle of that recent conflict.[2]

John Early, a supporter of the federal officials then occupying Texas, was an early member of the Texas Home Guard. He was having repeated run-ins with Drew Hasley, an older local citizen who had been a staunch supporter of the Confederacy. When Hasley's son, Samuel, returned from service in the war, he became active in the conflict with Early, escalating the feud. When the younger Hasley brought a local outlaw, Jim McRae, into the fight, Early sought federal troop intervention, which was granted. On July 30, 1869, McRae was ambushed and killed. Dr. Calvin Clark, an Early ally, was gunned down shortly afterward in Arkansas. The Hasley supporters soon disbanded and the feud faded.

Hatfield–McCoy

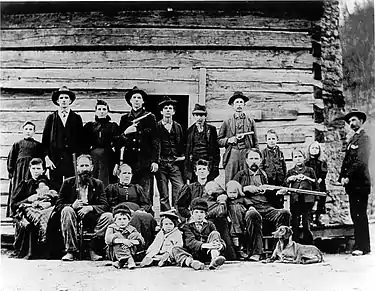

Perhaps the most infamous feud in the history of the U.S., the Hatfield–McCoy conflict is an iconic and legendary event in American folklore.[2] The Hatfields, of West Virginia, were led by William Anderson "Devil Anse" Hatfield. The McCoys, of Kentucky, were under the leadership of Randolph "Ole Ran’l" McCoy.

The feud began after the killing of Asa Harmon McCoy, an ex-Union soldier, who was gunned down on January 7, 1865, while hiding in a cave.[3] McCoy died at the hands of a group of Hatfield allies, and Confederate irregulars (named the "Logan Wildcats"), who had tracked him to his hiding place. The conflict was renewed thirteen years later when two McCoy family members killed a witness who was related to both families, and who had testified against them in a court case involving ownership of a stray pig.

The simmering feud escalated soon afterward, when Roseanna McCoy began a courtship with Johnson "Johnse" Hatfield, Devil Anse's son. Roseanna left her family to live with the Hatfields in West Virginia. In 1881, when Johnse abandoned the pregnant Roseanna, marrying her cousin instead, the bitterness between the two families grew. In 1882, Ellison Hatfield, brother of Devil Anse Hatfield, was killed in an election-day dispute by three of Roseanna's brothers, who themselves were killed by a Hatfield-led mob while in the custody of the law.

Between 1880 and 1891, the feud claimed more than a dozen members of the two families, becoming headline news around the country.

The feud reached its peak during the so-called 1888 New Years Night Massacre. Several of the Hatfield gang surrounded the McCoy cabin and opened fire on the sleeping family. The cabin was set on fire in an effort to drive Randolph McCoy into the open. He escaped by making a break, but two of his children were murdered, and his wife was beaten and left for dead.

In 1888, Wall Hatfield and eight others were arrested and ordered to stand trial for the New Years Night murders.[4] Seven received life imprisonment, while the eighth, Ellison "Cottontop" Mounts, was executed by hanging.[5] Fighting between the families eased following the hanging of Mounts. Trials, however, continued for several years, with the trial of Johnse Hatfield the last, in 1901.

Lee–Peacock

The Lee–Peacock feud took place in the four-corners area of the Texas counties of Fannin, Grayson, Collin, and Hunt.[2] It became a local, four-year extension of the American Civil War - lasting from 1867 to 1871 - in which an estimated 50 men lost their lives.

When the war broke out, a resident of the area, Bob Lee, immediately joined the Confederate Army, leaving his wife, three children, and his home in the care of his father Daniel. Near the end of the war, word reached Lee that a Union sympathizer, Lewis Peacock, had set up an organization in his home which was actively working for the protection of blacks and Union sympathizers. This was "The Union League", in Pilot Grove, Texas, less than seven miles from Lee's home. By the time that Lee and other ex-Confederate soldiers of the area returned to their homes in northeast Texas, the region was already roiling in conflict, as most area residents resented the intrusion of the Reconstruction soldiers stationed throughout the state.

Lee's doctor was murdered by Hugh Hudson, another Peacock sympathizer, and the feud immediately escalated. Hudson, the doctor's killer, was himself quickly killed, as were other combatants. Many were wounded, including Peacock. By the summer of 1868, the conflict had become so heated that Peacock requested help from the federal government, which promptly posted a $1,000 reward for Bob Lee's capture. The U.S. Cavalry, acting on a tip from an informant, shot Lee down on May 24, 1869; however, the fighting still continued. It wasn't until Lewis Peacock was himself killed, on June 13, 1871, that the feud ended.[6]

Sutton–Taylor

This notorious range war[7] began as a county law enforcement issue between the Taylor family, headed by Pitkin Taylor, brother of Creed Taylor, a renowned Texas Ranger, and local lawman William E. Sutton, a former Confederate soldier, who had moved with his family to DeWitt County, Texas, originally intending to simply raise cattle. The feud, which lasted a decade and cost at least 35 lives, has been called the longest and bloodiest in Texas history. It eventually involved the Texas State Police, the Texas Rangers, and the outlaw John Wesley Hardin.[8]

Sutton had become a deputy sheriff in Clinton, Texas, and on March 25, 1868, he shot and killed a Taylor kinsman, Charley Taylor, whom he was trying to arrest for horse theft. The following Christmas Eve, Sutton killed Buck Taylor and Dick Chisholm in a saloon in Clinton, after an argument regarding the sale of some horses. On August 23, 1869, the Sutton faction was suspected of the ambush and killing of Jack Hays Taylor.

In July 1870, Sutton was appointed to the State Police Force, serving under Captain Jack Helm (sometimes Helms). The police force was tasked with enforcing the "Reconstruction" policies of the federal government, but operated with somewhat of a free-hand, and more often than not returned with wanted suspects dead.[9]

On August 26, 1870, the Suttons were allegedly sent to arrest Henry and his brother William Kelly, who were both related by marriage to Pitkin Taylor, on a trivial charge. However, rather than arresting the men, the Suttons shot the Kellys. Due to his handling of the affair, Helm was dismissed from the State Police Force, though cleared of any wrongdoing.[9]

Pitkin Taylor was murdered in 1872 by Sutton supporters and was succeeded as head of the family by his son Jim Taylor, who vowed revenge on Sutton.[9]

John Wesley Hardin joins the feud

In early 1872, on-the-run outlaw John Wesley Hardin joined his cousin, Mannen Clements, in neighboring Gonzales County, Texas. There, Clements and his brothers were active in the cattle rustling or herding business working for Taylor family friends.

On May 15, 1873, Sutton family allies Jim Cox and Jake Christman were killed by the Taylor faction during a gunfight at Tomlinson Creek. Hardin later admitted that there were reports that he had led the fight in which these two men were killed, but would neither confirm nor deny his involvement.[10]

Two days later, in a May 17, 1873, gunfight, Hardin killed Dewitt County deputy sheriff, J.B. Morgan—serving under Helm, who was now sheriff of DeWitt County.[10] Hardin played a part in the assassination later that same day of Sheriff Helm in Albuquerque, Texas.[11] Hardin, Helm and Sam McCracken Jr. were gathered together talking in front of a blacksmith shop. Helm was unarmed, having left his revolvers at Mrs. McCracken's boarding house, where he was then residing. Jim Taylor advanced on Helm from behind and attempted to discharge his revolver, but it misfired. As Helm turned, Taylor fired again, this time striking Helm in the chest. Helm rushed Taylor with the intent to grapple with him, but Hardin discharged a double barrel shotgun, shattering his arm. As Helm attempted to flee into the blacksmith shop, Hardin held townspeople at gunpoint while Taylor unloaded the remaining five bullets from his revolver into him.[12] As Hardin and Taylor mounted their horses and prepared to ride away, they boasted that they had accomplished what they had come to do.[13] The next night, Hardin and other Taylor supporters surrounded the ranch house of Sutton family ally, Joe Tumlinson. A shouted truce was arranged and both sides signed a peace treaty in Clinton, Texas. However, within a year, violence once again broke out between the two sides.

The feud reached its apex when Jim and his cousin Billy Taylor gunned down William Sutton and a friend, Gabriel Slaughter, as they waited on a steamboat platform, in Indianola, Texas on March 11, 1874. Tired of the feud, Sutton had been planning to leave the area for good.[2][13] In retaliation, the Sutton faction caught and lynched three of the Taylor group, on June 22, 1874.[14] After this, the fighting continued, though with much less frequency. Jim Taylor was killed January 1, 1875. On November 17, 1875, Reuben H. Brown, the new leader of the Suttons and ex-marshal of Cuero, Texas, was shot down in the Exchange Saloon by Hardin, his last known action in the feud.[9]

In October 1876, after another outbreak of violence, Texas Ranger, Captain Jesse Lee Hall, led a force into Cuero, Texas to break up the feud for good. By January 1877, he and his supporting troop had put an end to the conflict.

Horrell–Higgins

The Horrell and Higgins families had both settled in the Lampasas County, Texas area several years before the American Civil War. By all accounts, the two families got along well for over a decade. However, by the early 1870s, the five 'Horrell boys': Mart, Tom, Merritt, Ben and Sam had been involved in numerous lawless activities. In January 1873, Lampasas County Sheriff, Shadrick T. Denson, attempted to arrest two brothers, Wash and Mark Short, who were friends of the Horrell family. Intervention by the Horrell brothers resulted in a gunfight in which Sheriff Denson was shot and killed. A county judge appealed to Texas Governor, Edmund J. Davis, for help. The Texas State Police dispatched a number of lawmen to the area to maintain order.

On March 14, 1873, state officers Wesley Cherry, Jim Daniels, and Andrew Melville arrested Bill Bowen, a brother-in-law to the Horrell brothers, for carrying a firearm (which Governor Davis had recently outlawed in the area). The officers then entered Jerry Scott's Saloon with Bowen in tow. After a verbal exchange with the Horrell brothers, who had been inside the saloon, a gunfight ensued. Four of the officers were killed, including Capt. Williams. Williams had managed to shoot and badly wound Mart Horrell, and his brother, Tom Horrell, was also among the wounded. Following the gunfight, more state police were sent to the county. Mart Horrell and three friends were arrested and taken to the Georgetown, Texas jail. However, a large crowd of Horrell family friends broke into the jail and freed them.

The brothers fled to Lincoln County, New Mexico, where later that same year, Ben Horrell was himself killed after he murdered a local law enforcement officer. In early February 1874, the brothers returned to Lampasas, but were no longer welcome. Shortly after their return, local rancher, John "Pink" Higgins, accused the Horrell brothers of rustling some of his cattle. The brothers were arrested, but were quickly acquitted. Although things were tense between the two families, no actions were taken by either side at that time.

The feud quickly escalated, when, on January 22, 1877 (while in the Wiley and Toland's Gem Saloon in Lampasas), John Higgins shot and killed Merritt Horrell in a gunfight. The three remaining Horrell brothers vowed revenge. On March 26, 1877, Tom and Mart Horrell were shot and wounded in an ambush, but both survived. John Higgins and Bob Mitchell were arrested for the action, but later acquitted.

Shootout at the Lampasas town square

On June 7, 1877, John Higgins rode into Lampasas accompanied by: brother-in-law, Bob Mitchell; Mitchell's brother, Frank; a friend, Bill Wren; and another brother-in-law, Ben Terry. The Horrell brothers and several friends were already in town, gathered at the town square. It is unknown who fired first, but it is believed that someone within the Horrell faction opened fire on the Higgins group. When the gunfight ended, Bill Wren had been wounded, Frank Mitchell had been killed, and Horrell faction members, Buck Waltrup and Carson Graham, had been killed.

All three Horrell brothers were arrested, and Texas Ranger, Major John B. Jones, acted as a mediator between the remaining members of the two factions. Less than one year later, Mart and Tom Horrell were arrested in Meridian, Texas for armed robbery and murder. While confined to the local jail, vigilantes broke in and shot and killed them both. Sam was the only remaining Horrell brother. He moved his family to Oregon in 1882, thus marking an end to the feud.

Lincoln County Feud

The Lincoln County Feud occurred in the Harts Creek community of Lincoln and Logan counties, West Virginia, between 1878 and 1890. Initially a personal vendetta between prominent residents Paris Brumfield and Canaan Adkins, the feud culminated in a bitter war between local timber barons and businessmen, including Allen Brumfield, John W. Runyon, and Benjamin Adams. The feud resulted in at least four deaths, numerous injuries and scuffles between factions, nationwide press coverage, and the extermination/out-migration of several key participants. It has been memorialized in at least one ballad and play, as well as through music recorded by John Hartford. Feud descendant and author Brandon Ray Kirk has written a history of the feud titled Blood in West Virginia: Brumfield v. McCoy, which draws primarily upon twenty years of research including oral histories with other feud descendants, newspaper accounts, and courthouse documents.[15]

Earp–Clanton

The Earp vendetta ride arose as a result of coordinated attacks (in December 1881 and again in March 1882) against the Earp brothers. These ambushes were in retaliation for their involvement in the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, in Tombstone, Arizona.

Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

The noted gun-battle had occurred on October 26, 1881, and was itself the climax of the Earp–Clanton family feud, simmering since the summer of 1880. Tensions between the Earps and both the Clantons and McLaurys increased through 1881, culminating in the historic gunfight. At the O.K. Corral, three deputized Earp brothers, Wyatt, Morgan and Virgil, along with Doc Holliday, had killed Billy Clanton, Frank McLaury and Tom McLaury. The Clanton and McLaury families were aligned with the "Outlaw Cowboys", a loosely knit outlaw group of families, friends and acquaintances then living in surrounding Cochise and Pima counties.[16]

Earp Vendetta Ride

The Earp Vendetta ride was a manhunt for the "Outlaw Cowboys" that Wyatt Earp held responsible for the maiming of his brother Virgil (the police chief of Tombstone, Arizona as well as a Deputy U.S. Marshal) the previous December,[17] and the recent assassination of his brother Morgan (also an assistant U.S. Marshal) the week before. When several suspects in the attacks were set free by the court − some owing to legal technicalities and others based on the strength of alibis provided by sympathetic confederates – Wyatt Earp decided he could not rely on civil justice, and took matters into his own hands.[18]

On March 20, 1882, a newly deputized United States Marshal Wyatt Earp formed a federal posse that began to scour Cochise and Pima counties for the purpose of hunting down and killing the men he thought guilty of the attacks. Wyatt and Warren Earp, Doc Holliday, John "Texas Jack" Vermillion, Dan Tipton, Charlie Smith, Fred Dodge, Johnny Green, and Lou Cooley made up the federal posse.

The killing began with the March 22, 1882, shooting of Frank Stilwell as he and several Outlaw Cowboys – including Ike Clanton – lay in ambush at the Tucson rail station. The Earp group was escorting the still invalid Virgil Earp, and his wife, to safety so they could be removed from the now dangerous Arizona Territory.

Cowboy confederate and Wyatt Earp rival, Cochise County Sheriff Johnny Behan, then formed his own posse and deputized a number of the outlaws, including Johnny Ringo, Phineas Clanton, Johnny Barnes and about 18 more men to ride after the federal posse and the five men "wanted" for the shooting of Stilwell.

Carrying federal arrest warrants for the assassins, the federal posse killed four men. The vendetta ride ended with the killing of "Curly Bill" Brocius and Johnny Barnes on April 15, 1882. The Earps and their associates then quickly headed for the New Mexico Territory, leaving Arizona Territory, and the feuding behind.

Tewksbury–Graham

An infamous range war in Pleasant Valley, Arizona, lasting from 1882–1892 had its origins in a feud between the Tewksbury and Graham families. The feud began in 1882 with a dispute involving the Tewksbury and Graham families and prominent cattleman James Stinson, who accused both families of rustling cattle from his ranch. After the Tewksburys resisted an attempt by Stinson's men to arrest them, Stinson offered the Grahams 50 heads of cattle and immunity from prosecution to give evidence against them. The Grahams agreed, but the discovery of the deal between the Grahams and Stinson led to the collapse of the case against the Tewksburys.[19] On the journey back to Pleasant Valley after the trial, Frank Tewksbury died of pneumonia and the Tewksburys blamed the Grahams and Stinson for his death.[20]

Stinson dissolved his herd and left Pleasant Valley in 1884 after his ranch foreman Marion McCann was attacked by members of the Tewksbury faction, causing the Grahams significant financial damage.[21] Tensions were worsened when the Tewksburys began driving sheep into the area, which many resented due to their destructive grazing habits.[22]

Violence erupted between the factions when Graham supporter Andy Blevins robbed and killed one of the Tewksbury's sheep herders. The Grahams and other local cattlemen then began conducting raids against the Tewksburys, backed by the Aztec Land and Cattle Company.[23] The Tewksburys in turn raised their own posses to raid the opposition with help from the Daggs Outfit, prominent sheep ranchers in the area.

In February 1887, a Navajo sheep herder working for the Tewksburys was killed and decapitated by Tom Graham, one of the heads of the Graham family. Later that year, Graham supporter Mart Blevins, father of Andy Blevins, disappeared near the Tewksburys ranch, and his son Hamp Blevins and Graham ally John Payne were shot to death in a confrontation with the Tewksburys the same day.[24] On August 17, William Graham was murdered by the Tewksburys. In retaliation, several Graham allies rode down to the Tewksbury ranch and Andy Blevins shot dead John Tewksbury Jr. and William Jacobs, both of whom were unarmed, initiating a shootout that lasted until the arrival of lawmen forced the Grahams to retreat.[25] When county sheriff Perry Owens attempted to arrest Blevins for the murders, a shootout ensued which resulted in the deaths of Blevins, his brother Sam and family friend Mose Roberts.[26] Fighting continued until every member of both families was dead except for Ed Tewksbury and Tom Graham.

The feud ended on August 2, 1892, when Tom Graham, the last surviving member of the Graham family, was gunned down in Tempe. Witnesses identified Ed Tewksbury and Tewksbury supporter John Rhodes as the killers, but a jury acquitted both men. Ed Tewksbury reportedly confessed to the murder on his deathbed.[27]

Brooks–McFarland

A family feud taking place between 1896 and 1902, centered in the Creek Nation of the old Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). It began with the death of Thomas Brooks on August 24, 1896. Brooks was killed during a botched holdup which was to originally include some members of the McFarland family in its execution. The Brooks family blamed the McFarland family for the death, and there followed a series of confrontations between the two clans that culminated in the historic shootout at Spokogee (now Dustin), Oklahoma on September 22, 1902.[28] During the gunfight, family patriarch, Willis Brooks, and his son, Clifton were killed, as well as McFarland family associate, George Riddle. John Brooks, brother of Clifton, lay seriously wounded. Survivors Jim and Joe McFarland, Alonzo Riddle (George's brother), and the wounded John Brooks, were arrested pending murder charges, though all were quickly released on bail.

The feud ended on October 10, 1902 when Jim McFarland was ambushed and killed near his home, possibly at the hands of Sam Baker, a Brooks ally.[29]

John Brooks left the area after recuperating from his wounds. Remaining Brooks brother, Henry, left the area soon after serving time for a subsequent arrest for horse theft. He died violently in a shootout with Alabama law enforcement in 1911. Sam Baker was killed October 7, 1911 by the son of an irate shopkeeper he had previously confronted. Willis Brooks' widow and family matriarch, "Old Jenny" Brooks, died on March 29, 1924, at the age of ninety-eight, and is said to have been proud that all of her sons had "died like men, with their boots on.''[30]

The members of McFarland faction were acquitted of any wrongdoing after the fight and continued living in the Dustin area.[31]

Reese–Townsend

The Reese–Townsend conflict, also called the Colorado County Feud, was a politically motivated feud which took place in the closing days of the Old West. The events of the conflict were centered in Columbus, Texas, but involved other parts of Colorado County before it was over. The feud ran from 1898 through 1907.[2] The feud resulted from a local political race that placed incumbent Sheriff Sam Reese against a former deputy sheriff, Larkin Hope. Former U.S. senator, Mark Townsend, was a power-broker who had been the deciding factor for several past contests for sheriff. He had pulled his support away from Reese, supporting Hope instead. This led to tensions between those in support of Reese, and the Townsend faction. When Hope was assassinated in downtown Columbus before the election was held, suspicion immediately fell on the Reese allies. Townsend's hand-picked replacement candidate, Will Burford, won the election.

On March 16, 1899, Reese was killed in a gunfight (provoked by him) with Townsend allies, and Reese's family vowed revenge.[32] From May 17, 1899 to May 17, 1907, five additional gunfights took place in the area, with the results that Dick Reese (Sam's brother), Arthur Burford, Hiram Clements and Jim Coleman lost their lives in the violence. Legendary Texas Ranger, Captain Bill McDonald, along with officer James Brooks and others, were dispatched to the area to restore order, and ended the fighting.[2]

Other notable U.S. feuds

See also

References

- ↑ "Legends of America: Feuds and Range Wars". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Handbook of Texas Online: Feuds". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ↑ Pearce, John Ed (1994). Days of Darkness: The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 227 pages. ISBN 0-8131-1874-3.

- ↑ Rice, Otis K (1982). The Hatfields and McCoys. The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 150 pages. ISBN 0-8131-1459-4.

- ↑ Rice p. 111.

- ↑ "Legends of America: The Lee-Peacock Feud". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ↑ "The Outlaw Cowboys". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ↑ Parsons, Chuck (2009). The Sutton-Taylor Feud: The Deadliest Blood Feud in Texas. University of North Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-57441-257-4.

- 1 2 3 4 "Legends of America". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- 1 2 Hardin, John W. (1896). The Life of John Wesley Hardin: As Written By Himself. ISBN 978-0-8061-1051-6. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ "Handbook of Texas Online: Helm Article". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ↑ Wise, Ken (March 2012). Hunter, Michelle (ed.). "The Trial of John Wesley Hardin". Texas Bar Journal. Austin, TX: State Bar of Texas. 75 (9): 202. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

Helm was formerly a captain in the infamous Texas State Police force under the Reconstruction Government. Violent and repressive, Helm and his henchmen reportedly killed 21 men in two months during the summer of 1869. Confronting Sheriff Helm in the street, Hardin shot Helm once, then held the townspeople at gunpoint while Taylor shot Helm several times in the head.

- 1 2 The Texas Vendetta, or, the Sutton-Taylor Feud. 1880. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ "Handbook of Texas online". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ↑ Park, Edwards. "Fatal Feuds and Futile Forensics". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ Kjensli, Jan. "Wyatt Earp - Wyatt Earp - man, life and legend". Archived from the original on March 23, 2012. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ↑ NOTE: Wyatt Earp, another target of the December ambush, was unharmed.

- ↑ Dodge, Fred; Lake, Carolyn (1999). Under Cover for Wells Fargo The Unvarnished Recollections of Fred Dodge. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-8061-3106-1.

- ↑ Hanchett, Leland J. Jr. (1994) Arizona's Graham-Tewkesbury Feud. Phoenix: Pine Rim Publishing. ISBN 0963778536 pp. 20–22

- ↑ Trimble, Marshall. "Pleasant Valley War". True West Magazine. February 3, 2017

- ↑ Hanchett (1994), pp. 26–28

- ↑ Tim Earhardt (2008), Zane Grey's Forgotten Ranch Tales from the Boles Homestead, Git A Rope! Publishing, Payson, Arizona, pp. 1412–13, ISBN 978-0803294202

- ↑ "O'Neill: Captain William Owen "Buckey" O'Neill (1860–1898)". Norm Tessman. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ↑ Hanchett (1994) Chapter 4: The Attack

- ↑ Joseph G. Rosa (1995), Age of the Gunfighter: Men and Weapons on the Frontier, 1840–1900, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 978-0806127613

- ↑ "The Legendary Sheriff Commodore Perry Owens". Guns of the Old West. October 27, 2014. October 27, 2014

- ↑ Julie McDonald (1991), Saints & Scoundrels: Colorful Characters of the American West, Amazon Digital Services, Inc. Ed Tewksbury and the Pleasant Valley War

- ↑ "1902 Gunfight at Spokogee". History Net: Where History Comes Alive - World & US History Online. June 12, 2006. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ↑ Butler, Ken (1997). Oklahoma Renegades: Their Deeds and Misdeeds. Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56554-231-0.

- ↑ Butler, pg. 50-52

- ↑ "Mountain Feuds of Aunt Jenny Johnson and the Brooks Boys". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ↑

- Columbus Texas Online History Columbus, TX History

External links

- Legends of America Early-Hasley: Feuds in the Old West

- West Virginia Division of Culture and History Archived June 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Hatfield–McCoy Feud

- Texas Marker Remembering The Horrell-Higgins Feud Historic Marker