Farmington, New Hampshire | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Farmington town hall | |

Seal | |

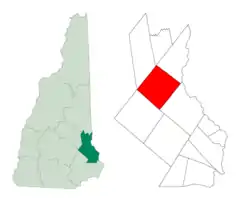

Location within Strafford County, New Hampshire | |

| Coordinates: 43°23′23″N 71°03′56″W / 43.38972°N 71.06556°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New Hampshire |

| County | Strafford |

| Settled | 1770s |

| Incorporated | 1798 |

| Villages |

|

| Government | |

| • Board of Selectmen[1] |

|

| • Town Administrator | Ken Dickie |

| Area | |

| • Total | 36.9 sq mi (95.7 km2) |

| • Land | 36.6 sq mi (94.8 km2) |

| • Water | 0.3 sq mi (0.9 km2) |

| Elevation | 285 ft (87 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 6,722 |

| • Density | 184/sq mi (70.9/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 03835 |

| Area code | 603 |

| FIPS code | 33-26020 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0873596 |

| Website | www |

Farmington is a town in Strafford County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 6,722 at the 2020 census.[4] Farmington is home to Blue Job State Forest, the Tebbetts Hill Reservation, and Baxter Lake.[5]

The town center, where 3,824 people resided at the 2020 census,[6] is defined by the U.S. Census Bureau as the Farmington census-designated place and is located at the junction of New Hampshire routes 75 and 153.

History

The native Abenaki people called the area Chemung, meaning "canoe place",[7] and used the three rivers—the Cocheco, the Ela, and the Mad—for transportation. They had a camping ground on Meetinghouse Hill, where they built birch bark canoes. Otherwise, the river valley was wilderness, through which the native peoples from the north traveled to and from Lake Winnipesaukee on their way to other areas and hunting grounds.

As European settlement of New Hampshire began to spread, the area that would become Farmington began as the Northwest Parish of Rochester, which was chartered in 1722. As the native peoples became displaced in the regions, they raided area settlements in and around Dover. To stop the raids, in 1721 the colonial assembly in Portsmouth approved construction of a fort at the foot of the lake, with a soldiers' road built from Dover to supply it. In 1722, Bay Road was surveyed and completed. Along its course the town of Farmington would grow.

The last native attack in the general region occurred in 1748, and by 1749 the Native Americans living in the area had disappeared from either warfare or disease. Farmers cultivated the rocky soil, and gristmills used water power of streams to grind their grain. Sawmills cut the abundant timber, and the first frame house at the village was built in 1782. In 1790, Jonas March from Portsmouth established a store, behind which teamsters unloaded on his dock the lumber he traded. The area became known as "March's Dock", "Farmington Dock", and finally just "The Dock".

Inhabitants of the Northwest Parish were taxed to support both the meetinghouse and minister on Rochester Hill about 12 miles (19 km) away, a distance which made attendance difficult. A movement began in the 1770s to establish a separate township, and in 1783 a petition for charter was submitted to the state legislature. It was denied, but another petition in 1798 was granted. With about 1,000 inhabitants, Farmington was incorporated.[8] In 1800, a 40-by-50-foot (12 by 15 m), two-story meetinghouse was erected on Meetinghouse Hill. The same year, John Wingate established a blacksmithy. He would also become proprietor of Wingate's Tavern.

In the 19th century, the community developed a prime shoemaking industry, and was one of the first places to use automated machines instead of handwork. In 1836, shoe manufacturing began at a shop on Spring Street built by E. H. Badger, although it was soon abandoned to creditors. Martin Luther Hayes took over the business, and by 1840 was successful enough to enlarge the building. The town would be connected by railroad to Dover in 1849, with the line extended to Alton Bay in 1851. Shoes were shipped to Boston to be sold at semi-annual auctions for 50 cents a pair.[8]

Following the Civil War, the shoe business boomed and numerous factories were built. Farmington was known as "The Shoe Capital of New Hampshire" for some time. Other factories produced knives, knit underwear, wooden boxes, wooden handles and carriages. A large fire in 1875 destroyed much of the center of town, but the community survived. Brushes were manufactured by the F. W. Browne Company, from which Booker T. Washington ordered twelve street brooms in 1915 for use at the Tuskegee Institute. The town was home to five blacksmith shops, a movie theater, and two hotels. The Panic of 1893 closed all but two large shoe factories. Local industries faded in the latter half of the 20th century. Most of the factories were either demolished or converted into other purposes.

Central Street in 1908

Central Street in 1908 Cochecho River in 1912

Cochecho River in 1912 Central House in 1913

Central House in 1913 Opera House in 1914

Opera House in 1914 Shoe factory in 1915

Shoe factory in 1915

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, Farmington has a total area of 36.9 square miles (95.7 km2), of which 36.6 square miles (94.8 km2) are land and 0.3 square miles (0.9 km2) are water, comprising 0.95% of the town.[3] The town is drained by the Cochecho River and its tributaries the Ela River, Mad River, and Rattlesnake River. Baxter Lake, on the southeast border, is the largest water body in the town. Part of the Blue Hills Range, foothills of the White Mountains, is in the southwest. The highest point in Farmington is Blue Job Mountain, at 1,350 feet (410 m) above sea level, near the town's southwest border. Farmington lies almost fully within the Piscataqua River (Coastal) watershed, with the westernmost corner of town located in the Merrimack River watershed.[9]

The town is crossed by New Hampshire Routes 11, 75, and 153.

Adjacent municipalities

- Middleton, New Hampshire (north)

- Milton, New Hampshire (northeast)

- Rochester, New Hampshire (southeast)

- Strafford, New Hampshire (southwest)

- Barnstead, New Hampshire (west at one point)

- Alton, New Hampshire (northwest at one point)

- New Durham, New Hampshire (northwest)

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 786 | — | |

| 1800 | 1,029 | 30.9% | |

| 1810 | 1,272 | 23.6% | |

| 1820 | 1,716 | 34.9% | |

| 1830 | 1,464 | −14.7% | |

| 1840 | 1,380 | −5.7% | |

| 1850 | 1,699 | 23.1% | |

| 1860 | 2,275 | 33.9% | |

| 1870 | 2,063 | −9.3% | |

| 1880 | 3,044 | 47.6% | |

| 1890 | 3,064 | 0.7% | |

| 1900 | 2,265 | −26.1% | |

| 1910 | 2,621 | 15.7% | |

| 1920 | 2,461 | −6.1% | |

| 1930 | 2,698 | 9.6% | |

| 1940 | 3,095 | 14.7% | |

| 1950 | 3,454 | 11.6% | |

| 1960 | 3,287 | −4.8% | |

| 1970 | 3,588 | 9.2% | |

| 1980 | 4,630 | 29.0% | |

| 1990 | 5,739 | 24.0% | |

| 2000 | 5,774 | 0.6% | |

| 2010 | 6,786 | 17.5% | |

| 2020 | 6,722 | −0.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] | |||

As of the 2010 census, there were 6,786 people, 2,592 households, and 1,813 families residing in the town. The population density was 180.8 inhabitants per square mile (69.8/km2). There were 2,832 housing units, at an average density of 76.1 units per square mile (29.4/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 96.8% white, 0.5% African American, 0.3% American Indian or Alaska Native, 0.5% Asian, 0.1% Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, 0.2% some other race, and 1.7% from two or more races. 0.8% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 2,592 households counted at the 2010 census, out of which 29.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.0% were headed by married couples living together, 12.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.1% were non-families. 22.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.62, and the average family size was 3.01.

In the town, the 2010 population was spread out, with 23.9% under the age of 18, 8.5% from 18 to 24, 26.4% from 25 to 44, 30.2% from 45 to 64, and 11.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39.2 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.0 males.[11]

For the period 2012–2016, the estimated annual median income for a household in the town was $52,305, which was 9% below the county average, and 17% below the state average. The median income for a family was $68,693. Male full-time workers had a median income of $45,476 versus $35,958 for females. The per capita income for the town was $26,111. 7.2% of families and 11.5% of the total population were below the poverty line, along with 17.5% of people under the age of 18 and 3.2% of people 65 or older.[12]

Although the town has about the same percentage of population below the poverty line as does the county, the town has a disproportionate share of the county's low-income residents living just above the poverty line, and a disproportionately small share of the county's affluent households. This means that with changing socio-economic pressures, a larger portion of the town's population is at risk of falling into poverty than is the case elsewhere in the county.[13]

Notable people

- Shirley Barker (1911–1965), author, poet, librarian

- Harry Bemis (1874–1947), catcher with the Cleveland Naps

- Nehemiah Eastman (1782–1856), lawyer, banker, politician

- Winfield Scott Edgerly (1846–1927), U.S. Army brigadier general

- Joseph W. Furber (1814–1884), Minnesota Whig legislator

- Joseph Hammons (1787–1836), U.S. congressman

- Wingate Hayes (1823–1877), U.S. Attorney, Speaker of Rhode Island House of Representatives

- Alonzo Nute (1826–1892), U.S. congressman

- Raymond Pearl (1879–1940), biologist, regarded as one of the founders of biogerontology

- Lawrence Lee Pelletier (1914–1995), 16th president of Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania

- Mary Lemist Titcomb (1852–1932), librarian

- Clara Augusta Jones Trask (1839–1905), dime novelist

- Henry Wilson (1812–1875), 18th Vice-President of the United States (1873–1875)

References

- ↑ "Board of Selectmen". Town of Farmington. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ↑ "Board of Selectmen". Town of Farmington. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- 1 2 "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files – New Hampshire". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- ↑ "Census - Geography Profile: Farmington town, Strafford County, New Hampshire". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ↑ Google Maps

- ↑ "Census - Geography Profile: Farmington CDP, New Hampshire". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ↑ The History of Farmington, NH, from the Days of the Northwest Parish to the Present Time. Farmington, NH: The Foster Press. 1976.

- 1 2 A. J. Coolidge & J. B. Mansfield, A History and Description of New England; Boston, Massachusetts 1859

- ↑ Foster, Debra H.; Batorfalvy, Tatianna N.; Medalie, Laura (1995). Water Use in New Hampshire: An Activities Guide for Teachers. U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Geological Survey.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Farmington town, Strafford County, New Hampshire". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ↑ "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2012-2016 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates (DP03): Farmington town, Strafford County, New Hampshire". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Quick Facts Farmington town, Strafford County, New Hampshire".

Further reading

- The Bicentennial History Committee, The History of Farmington, NH, from the Days of the Northwest Parish to the Present Time, The Foster Press, Farmington, NH 1976. This title is available from the Farmington Historical Society.

- Farmington Historical Society, "Images of America: Farmington", Arcadia Publishing, an imprint of the Chalford Publishing Corporation, Dover, NH, 1997. This title is available from the Farmington Historical Society.

- Farmington Historical Society, Online Museum of Farmington History.

- Farmington Historical Society, Online Archives of the Farmington News.

- Puddledock Press of Farmington New Hampshire, Archives of the Puddledock Press.