| First Carlist War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Carlist Wars | |||||||

The Battle of Mendigorría, 16 July 1835 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: |

Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Carlists: 15,000–60,000 |

Liberals: 15,000–65,000 French: 7,700 British: 2,500 Portuguese: 50 | ||||||

The First Carlist War was a civil war in Spain from 1833 to 1840, the first of three Carlist Wars. It was fought between two factions over the succession to the throne and the nature of the Spanish monarchy: The conservative and devolutionist supporters of the late king's brother, Carlos de Borbón (or Carlos V), became known as Carlists (carlistas), while the progressive and centralist supporters of the regent, Maria Christina, acting for Isabella II of Spain, were called Liberals (liberales), cristinos or isabelinos. It is considered by some authors to be the largest and most deadly civil war of the period.[1]

The main Carlist forces were split in three geographically distinct armies where Carlist support was strongest: 'North', 'Maestrazgo', and 'Catalonia', which by and large operated independently from each other.[2] Several independent, but nominally Carlist bands also waged a guerrilla war in mountain areas as far south as La Mancha and Andalusia, but were derided as bandoleros (bandits) by the Christino liberal government.[3][4]

Aside from being a war of succession about the question of who was the rightful successor to Ferdinand VII of Spain, the Carlists' goal was the return to a traditional monarchy, while the Liberals sought to defend the constitutional monarchy. Portugal, France and the United Kingdom supported the regency and sent volunteer and even regular forces to confront the Carlist army.

Historical background

At the beginning of the 19th century, the political situation in Spain was extremely problematic. During the Peninsular War, the Cortes of Cádiz – which served as the Regency for the deposed Ferdinand VII – collaborated on the Spanish Constitution of 1812. After the war, when Ferdinand VII returned to Spain (1814), he annulled the constitution in the Manifesto of Valencia and became an absolutist king, governing by decrees and restoring the Spanish Inquisition, which had been abolished by Joseph I, brother of Napoleon I.

The 1805 Battle of Trafalgar had all but shattered the Spanish navy, with the Peninsular War leaving Spanish society overwhelmed by continuous warfare and badly damaged by looting. While the Spanish Empire collapsed, the maritime trade in the Americas and Philippines fell to a trickle, and Spain's military struggled to keep their colonies, with Mexico getting its independence in 1821. The overseas revenue was at a historic low, and the royal coffers were empty. Balancing the books and recruitment to the military became an overriding concern for the Spanish Crown, with the governments under King Ferdinand VII failing to provide new solutions or stability.

During the Trienio Liberal (1820-1823), the progressives, who were allied to the business classes, resorted to international money lenders in an attempt to avert the economic meltdown Spain was facing. They turned to Paris, and particularly London, where many liberals (many of them Freemasons) had fled on Ferdinand VII's return in 1814. In London and Paris, negotiations were opened respectively with Nathan Rothschild and James Rothschild. They bailed out the Spanish liberal regime, supported by Great Britain, which consistently supported liberal movements in Europe and also had vested interest in securing the debt engaged in previous years.[5]

The 1823 intervention of a reactionary international alliance, the Sacred Alliance, restored Ferdinand VII on the Spanish throne, who repudiated the debts incurred by the 1820-1823 liberal rulers with the Rothschilds. For more than a decade, the unserviced liberal debt was a persistent sticking point with these financiers during talks for new loan requests.[6]

Against a backdrop of on-off bankruptcy and solvency issues, towards the end of his life, Ferdinand VII promulgated the Pragmatic Sanction of 1830, giving hopes to the liberals. Ferdinand VII of Spain had no male descendant, but two daughters, Isabella (later Isabella II) and Luisa Fernanda. The "Pragmatic Sanction" allowed Isabella to become Queen after his death. This overrode the rights of Carlos de Borbón, the king's brother, to the succession,[7] He and his followers, such as Secretary of Justice Francisco Tadeo Calomarde, pressed Ferdinand to change his mind. But the agonizing Ferdinand kept to his decision and, when he died on 29 September 1833, Isabella became queen. As she was only a child, a regent was needed, so her mother Queen Consort Maria Christina was appointed. Queen Christina was twenty seven years old when her husband's death made her regent at the instructions of the late king's will. Before the king's death had been publicly announced, the conservative Francisco Cea Bermúdez summoned a council of state to pledge loyalty to the Queen, but the government already expected reactionary elements to contest the succession. [8]

A strong absolutist party feared that the regent Maria Christina would make liberal reforms, and sought another candidate for the throne. The natural choice, based on Salic Law, was Ferdinand's brother Carlos. The differing views on the influence of the army and the Church in governance, as well as the forthcoming administrative reforms, paved the way for the expulsion of the Conservatives from the higher governmental circles. Uprisings occurred immediately after the death of the king was announced, but Don Fernando did not acknowledge them at first. He nonetheless pressed his claims to the throne by giving his royal support to the Bermudez government, a motion which the government rebuffed. [8]

Viewing the pretender as a threat to the state, the government began motions to prosecute Don Carlos, which he responded to by calling his followers to arms on November 4, 1833 and an insurgency began to form in the Basque Mountains. [9]

Cea Bermudez's centrist government (October 1832-January 1834) inaugurated the return to Spain of many exiles from London and Paris, e.g. Juan Álvarez Mendizabal (born Méndez). The rise of Cea Bermudez was followed by a closer collaboration and understanding with the Rothschilds, who in turn clearly encouraged the former's reforms and liberalization, i.e. the new liberal regime and the incorporation of Spain to the European financial system.[10] However, with state coffers yet again empty, the impending war, and the Trienio Liberal loan issue with the Rothschilds still not settled, Cea Bermudez's government fell.[11] To gain widespread and middle class support against the Carlists, the government began to embrace progressive measures and defining the regency of Queen Christina as a liberal monarchy. The conservative Bermudez was dismissed and replaced by the moderate liberal Francisco Martínez de la Rosa in January, 1834. That April the government produced a new constitution known as the Royal Statute.[12]

Faced with war breaking out in the Basque Country, the envoy of regent Maria Cristina's government, the Marquis of Miraflores (a middle-of-the-road liberal), contacted London's City bankers to open a line of credit with the Spanish Treasury (thus pay the next installment of external debt due in July 1834 and get new credit), as well as the British Government in order to garner its political endorsement. An agreement with Nathan and James Rothschild and a loan advance of 500,000 pounds to the Marquis of Miraflores paved the way to the establishment of the Quadruple Alliance that sealed British and French protection to the Spanish government, including military operations (April 1834).[13]

As written by one historian:

The first Carlist war was fought not so much on the basis of the legal claim of Don Carlos, but because a passionate, dedicated section of the Spanish people favored a return to a kind of absolute monarchy that they felt would protect their individual freedoms (fueros), their regional individuality and their religious conservatism.[14]

A vivid summary of the war describes it as follows:

The Christinos and Carlists thirsted for each other's blood, with all the fierce ardour of civil strife, animated by the memory of years of mutual insult, cruelty, and wrong. Brother against brother – father against son – best friend turned to bitterest foe – priests against their flocks – kindred against kindred.[15]

The autonomy of Aragon, Valencia and Catalonia had been abolished in the 18th century by the Nueva Planta Decrees that created a centralised Spanish state. In the Basque Country, the kingdom status of Navarre and the separate status of Álava, Biscay, and Gipuzkoa were challenged in 1833 during the central government's one-sided territorial division of Spain. The resentment against the growing intervention of Madrid (e.g. attempts to take over Biscayan mines in 1826) and the loss of autonomy was considerably strong.

Basque reasons for Carlist uprising

The Spanish liberal government wanted to suppress the Basque fueros and to move the customs borders to the Pyrenees. Since the 18th century, a new emergent class had an interest in weakening the powerful Basque nobility and their influence in commerce, which extended throughout the world with the help of the Jesuit order. The centralisers in the Spanish government supported some of the great powers against Basque merchants from at least since the time of the abolition of the Jesuit order and the Godoy regime. First, they sided with the French Bourbons to suppress the Jesuits, following the formidable changes in North America after the victory of the United States in the American Revolutionary War. When the War of the Pyrenees came to an end in 1795 with the Peace of Basel, the Basques feared the abolition of their self-government and Godoy panicked at the prospect of the still-autonomous Basque region switching allegiances to Revolutionary France and detaching itself from Spain. In the peace, Spain gave up the eastern two-thirds of the island of Hispaniola in exchange for keeping Gipuzkoa.[16]

However, King Ferdinand VII found an important support base in the Basque Country. The 1812 Constitution of Cádiz had suppressed Basque home rule and was couched in terms of a unified Spanish nation, which rejected the existence of the Basque nation, so the new Spanish king garnered the endorsement of the Basques as long as he respected the Basque institutional and legal framework. Most foreign observers, including Charles F. Henningsen, Michael B. Honan and Edward B. Stephens, English writers and first-hand witnesses of the First Carlist War and spent time in the Basque districts, were highly sympathetic to the Carlists, which they regarded as representing the cause of Basque home rule. Probably the only exception was John Francis Bacon, a diplomat residing in Bilbao during the Carlist siege of (1835), who also praising Basque governance but could not hide his hostility towards the Carlists, whom he regarded as "savages." He went on to contest his compatriots' approach, denied a connection between the Carlist cause and the defense of the Basque liberties, and speculated that Carlos V would be quick to erode or suppress them if he took the Spanish throne.

The privileges of the Basque provinces are odious to the Spanish nation, of which Charles is so well aware, that if he was king of Spain next year, he would quickly find excuses for infringing them, if not their total abolition. A representative government will endeavour to raise Spain to a level with the Basque provinces, – a despot, to whom the very name of freedom is odious, would strive to reduce the provinces to the same low level with the rest.[17]

Similar to what John Adams had pointed out 60 years before, John F. Bacon (Six years in Biscay..., 1838) considered the Basques living to the north of the Ebro river as free citizens, as compared to the Spanish whom he sees as "a mere flock" liable to be mistreated by their masters. For Edward B. Stephens, the Basques were fighting at once for their own sources of legitimacy, their practical freedom, for the rights of their sovereign, and their own constitutional foundations.[18] The excellence of the Basque home rule and its republican character is also highlighted by other authors, such as Wentworth Webster.[19] A deeper insight into the Basques and their relation to the Spanish during this period is offered by Sidney Crocker and Bligh Barker (1839), stating that:

the Vasques, or as they term themselves, the Escaldunes, do not consider themselves Spaniards, and differ widely from them, in character and language.[20]

The interests of the Basque liberals were divided. On the one side, fluent cross-Pyrenean trade with other Basque districts and France was highly valued, as well as unrestricted overseas transactions. The former had been strong up to the French Revolution, especially in Navarre, but the new French national arrangement (1790) had abolished the separate legal and fiscal status of the French Basque districts. Despite difficulties, on-off trade continued during the period of uncertainty prevailing under the French Convention, the War of the Pyrenees (1793-1795), Manuel Godoy's tenure in office, and the Peninsular War. Eventually, Napoleonic defeat left cross-border commercial activity struggling to take off after 1813.

Overseas commerce was badly affected by the end of the Guipuzcoan Company of Caracas (1785), the French-Spanish defeat at the Battle of Trafalgar (1805), independence movements in Latin America, the destruction of San Sebastián (1813), and the eventual breakup of the Royal Philippine Company (1814). By 1826, the Spanish merchant fleet, which consisted in large part of Basque officers and sailors, was in complete decline due to being supplanted by British shipping (that had been established as a result of the Pax Britannica).[21]

Notwithstanding the ideology of Basque liberals, overall supportive of home rule, the Basques were getting choked by the above circumstances and customs on the Ebro on account of the high levies enforced on them by the successive Spanish governments after 1776. Many Basque liberals advocated in turn for the relocation of the Ebro customs to the Pyrenees and the encouragement of a Spanish market. On Ferdinand VII's death in 1833, the minor Isabella II was proclaimed queen, with Maria Christina acting as regent. In November, a new Spanish institutional arrangement was designed by the incoming government in Madrid, homogenising Spanish administration according to provinces and conspicuously overruling Basque institutions. Anger and disbelief spread in the Basque districts.

Contenders

The people of the western Basque provinces (ambiguously called "Biscay" up to that point) and Navarre sided with Carlos because ideologically Carlos was close to them and more importantly because he was willing to uphold Basque institutions and laws. Some historians claim that the Carlist cause in the Basque Country was a pro-fueros cause, but others (Stanley G. Payne) contend that no connection to the emergence of Basque nationalism can be postulated. Many supporters of the Carlists cause believed a traditionalist rule would better respect the ancient region specific institutions and laws established under historical rights. Navarre and the rest of the Basque provinces held their customs on the Ebro river. Trade had been strong with France (especially in Navarre) and overseas up to the Peninsular War (up to 1813), but getting sluggish thereafter.

Another important reason for the massive mobilisation of the western Basque provinces and Navarre for the Carlist cause was the tremendous influence of the Basque clergy in the society, one that still addressed to them in their own language, Basque, unlike school and administration, institutions where Spanish had been imposed by then. The Basque pro-fueros liberal class under the influence of the Enlightenment and ready for independence from Spain (and initially at least allegiance to France) was put down by the Spanish authorities at the end of the War of the Pyrenees (San Sebastián, Pamplona, etc.). As of then, the strongest partisans of the region specific laws were the rural based clergy, nobility and lower class—opposing new liberal ideas largely imported from France. Salvador de Madariaga, in his book Memories of a Federalist (Buenos Aires, 1967), accused the Basque clergy of being "the heart, the brain and the root of the intolerance and the hard line" of the Spanish Catholic Church.

On the other side, the liberals and moderates united to defend the new order represented by María Cristina and her three-year-old daughter, Isabella. They controlled the institutions, almost the whole army, and the cities; the Carlist movement was stronger in rural areas. The liberals had the crucial support of United Kingdom, France and Portugal, support that was shown in the important credits to Cristina's treasury and the military help from the British (British Legion or Westminster Legion under General de Lacy Evans), the French (the French Foreign Legion), and the Portuguese (a Regular Army Division under General Count of Antas). The Liberals were strong enough to win the war in two months, but an inefficient government and the dispersion of the Carlist forces gave Carlos time to consolidate his forces and hold out for almost seven years in the northern and eastern provinces.

As Paul Johnson has written, "both royalists and liberals began to develop strong local followings, which were to perpetuate and transmute themselves, through many open commotions and deceptively tranquil intervals, until they exploded in the merciless civil war of 1936-39."[22]

Combatants

Both sides raised special troops during the war. The Liberal side formed the volunteer Basque units known as the Chapelgorris, while Tomás de Zumalacárregui created the special units known as aduaneros. Zumalacárregui also established the unit known as Guías de Navarra from Liberal troops from La Mancha, Valencia, Andalusia and other places who had been taken prisoner at the Battle of Alsasua (1834). After this battle, they had been faced with the choice of joining the Carlist troops or being executed.

The term Requetés was at first applied to just the Tercer Batallón de Navarra (Third Battalion of Navarre) and subsequently to all Carlist combatants.

The war attracted independent adventurers, such as the Briton C. F. Henningsen, who served as Zumalacárregui's chief bodyguard (and later was his biographer), and Martín Zurbano, a contrabandista or smuggler, who:

soon after the commencement of the war sought and obtained permission to raise a body of men to act in conjunction with the queen's troops against the Carlists. His standard, once displayed, was resorted to by smugglers, robbers, and outcasts of all descriptions, attracted by the prospect of plunder and adventure. These were increased by deserters...[23]

About 250 foreign volunteers fought for the Carlists; the majority were French monarchists, but they were joined by men from Portugal, Britain, Belgium, Piedmont-Sardinia, and the German states.[24] Friedrich, Prince of Schwarzenberg fought for the Carlists, and had taken part in the French conquest of Algeria and the Swiss civil war of the Sonderbund. The Carlists' ranks included such men as Prince Felix Lichnowsky, Adolfo Loning, Baron Wilhelm Von Radhen and August Karl von Goeben, all of whom later wrote memoirs concerning the war.[24]

The Liberal generals, such as Vicente Genaro de Quesada and Marcelino de Oraá Lecumberri, were often veterans of the Peninsular War, or of the wars resulting from independence movements in South America. For instance, Jerónimo Valdés participated in the battle of Ayacucho (1824).

Both sides executed prisoners of war by firing squad; the most notorious incident occurred at Heredia, when 118 Liberal prisoners were executed by order of Zumalacárregui. The British attempted to intervene, and through Lord Eliot, the Lord Eliot Convention was signed on April 27–28, 1835.

The treatment of prisoners of the First Carlist War became regulated and had positive effects. A soldier of the British Auxiliary Legion wrote:

The British and Chapelgorris who fell into their hands [the Carlists], were mercilessly put to death, sometimes by means of tortures worthy of the North American Indians; but the Spanish troops of the line were saved by virtue, I believe, of the Eliot treaty, and after being kept for some time in prison, where they were treated with sufficient harshness, were frequently exchanged for an equal number of prisoners made by the Christinos.[25]

However, Henry Bill, another contemporary, wrote that, although "it was mutually agreed upon to treat the prisoners taken on either side according to the ordinary rules of war, a few months only elapsed before similar barbarities were practiced with all their former remorselessness."[26]

War

Northern front

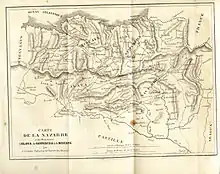

The war was long and hard, and the Carlist forces (labeled "the Basque army" by John F. Bacon) achieved important victories in the north under the direction of the brilliant general Tomás de Zumalacárregui. The Basque commander swore an oath to uphold home rule in Navarre (fueros), subsequently being proclaimed commander in chief of Navarre. The Basque regional governments of Biscay, Álava, and Gipuzkoa followed suit by pledging obedience to Zumalacárregui. He took to the bush in the Amescoas (to become the Carlist headquarters, next to Estella-Lizarra), there making himself strong and avoiding the harassment of the Spanish forces loyal to Maria Christina (Isabella II). 3,000 volunteers with no resources came to swell his forces.

In summer 1834, Liberal (Isabeline) forces set fire to the Sanctuary of Arantzazu and a convent of Bera, while Zumalacárregui showed his toughest side when he had volunteers refusing to advance over Etxarri-Aranatz executed. The Carlist cavalry engaged and defeated in Viana an army sent from Madrid (14 September 1834), while Zumalacárregui's forces descended from the Basque Mountains over the Álavan Plains (Vitoria), and prevailed over general Manuel O'Doyle. The veteran general Espoz y Mina, a Liberal Navarrese commander, attempted to drive a wedge between the Carlist northern and southern forces, but Zumalacárregui's army managed to hold them back (late 1834).

In January 1835, the Carlists took over Baztan in an operation where the general Espoz y Mina narrowly escaped a severe defeat and capture, while the local Liberal Gaspar de Jauregi Artzaia ('the Shepherd') and his chapelgorris were neutralized in Zumarraga and Urretxu. By May 1835, virtually all Gipuzkoa and seigneury of Biscay were in Carlist hands. Opposing his advisers and Zumalacárregui's plan, Carlos V decided to conquer Bilbao, defended by the Royal Navy and the British Auxiliary Legion. With such an important city in his power, the Prussian or Russian Tsarist banks would give him credit to win the war; one of the most important problems for Carlos was a lack of funds.

In the siege of Bilbao, Zumalacárregui was wounded in the leg by a stray bullet. The wound was not serious, he was treated by a number of doctors, famously by Petrikillo (nowadays meaning in Basque 'quack' or 'dodgy healer'). The relationship of the pretender to the throne and the commander in chief was at least distant; not only had they differed in operative strategy, but Zumalacárregui's popularity could undermine Carlos's own authority, as in the early stages of the war, the Basque general was offered the crown of Navarre and the lordship of Biscay as king of the Basques.[27] The injury did not heal properly, and finally General Zumalacárregui died on June 25, 1835. Many historians believe the circumstances of his death were suspicious, and have noted that the general had many enemies in the Carlist court; however, to date no further light has been shed on this point.

In the European theatre, all the great powers backed the Isabeline army, as many British observers wrote in their reports. Meanwhile, in the east, Carlist general Ramón Cabrera held the initiative in the war, but his forces were too few to achieve a decisive victory over the Liberal forces loyal to Madrid. In 1837, the Carlist effort culminated in the Royal Expedition, which reached the walls of Madrid, but subsequently retreated after the Battle of Aranzueque.

Southern front

In the south, the Carlist general Miguel Gómez Damas attempted to establish a strong position there for the Carlists, and he left Ronda on November 18, 1836, entering Algeciras on November 22. But, after Gómez Damas departed from Algeciras, he was defeated by Ramón María Narváez y Campos at the Battle of Majaceite. An English commentator wrote that "it was at Majaciete that [Narváez] rescued Andalucía from the Carlist invasion by a brilliant coup de main, in a rapid but destructive action, which will not readily be effaced from the memory of the southern provinces."[28]

At Arcos de la Frontera, the Liberal Diego de Leon managed to detain a Carlist column by his squadron of 70 cavalry until Liberal reinforcements arrived.

Ramon Cabrera had collaborated with Gómez Damas in the expedition of Andalusia where, after defeating the Liberals, he occupied Córdoba and Extremadura. He was pushed out after his defeat at Villarrobledo in 1836.

End

After the death of Zumalacárregui in 1835, the Liberals slowly regained the initiative but were not able to win the war in the Basque districts until 1839. They failed to recover the Carlist fortress of Morella and suffered a defeat at the Battle of Maella (1838).

The war effort had taken a heavy toll on Basque economy and regional public finances with a population shaken by a myriad of war related plights—human losses, poverty, disease—and tired with Carlos's own absolutist ambitions and disregard for their self-government. The moderate Jose Antonio Muñagorri negotiated as of 1838 a treaty in Madrid to put an end to war ("Peace and Fueros") leading to the Embrace of Bergara (also Vergara), ratified by Basque moderate liberals and disaffected Carlists across all the main cities and countryside.

The war in the Basque Country ended with the Convenio de Bergara, also known as the Abrazo de Bergara ("the Embrace of Bergara", Bergara in Basque) on 31 August 1839, between the Liberal general Baldomero Espartero, Count of Luchana and the Carlist General Rafael Maroto. Some authors have written that General Maroto was a traitor who forced Carlos to accept the peace with little focus as to the precise context in the Basque Country.

In the east, General Cabrera continued fighting, but when Espartero conquered Morella and Cabrera in Catalonia (30 May 1840), the fate of the Carlists was sealed. Espartero progressed to Berga, and by mid-July 1840 the Carlist troops had to flee to France. Considered a hero, Cabrera returned to Portugal in 1848 for the Second Carlist War.

Consequences

The Embrace of Bergara (August 1839) put an end to war in the Basque districts. The Basques managed to keep a reduced version of their previous home rule (taxation, military draft) in exchange for their unequivocal incorporation into Spain (October 1839), now centralized, and divided into provinces.

The October 1839 Act was confirmed in Navarre, but events took an unexpected turn in Madrid when General Baldomero Espartero rose to office with the support of the Progressives in Spain. In 1840, he became premier and regent. The financial and trading bourgeoisie burgeoned, but after Carlist war the Treasury's coffers were depleted and the army pending discharge.

In 1841, a separate treaty was signed by officials of the Council of Navarre (the Diputación Provincial, established in 1836), such as the Liberal Yanguas y Miranda, without the mandatory approval of the parliament of the kingdom (the Cortes). That compromise (called later the Ley Paccionada, the Compromise Act) accepted further curtailments to self-government, and more importantly officially turned the Kingdom of Navarre into a province of Spain (August 1841).

In September 1841, Espartero's uprising had its follow-up in the military occupation of the Basque Country, and subsequent suppression by decree of Basque home rule altogether, definitely bringing the Ebro customs over to the Pyrenees and the coast. The region was gripped by a wave of famine, and many took to overseas emigration at either side of the Basque Pyrenees, to America.

Espartero's regime came to an end in 1844 after the moderate Conservatives gained momentum, and a settlement was found for the stand-off in the Basque Provinces.

Chronology of battles

- Battle of Mayals (April 10, 1834) - Liberal victory

- Battle of Alsasua (April 22, 1834) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Gulina (June 18, 1834) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Alegría de Álava (October 27, 1834) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Venta de Echávarri (October 28, 1834) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Mendaza (December 12, 1834) - Liberal victory

- First Battle of Arquijas (December 15, 1834) - Liberal victory

- Second Battle of Arquijas (February 5, 1835) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Artaza (April 22, 1835) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Mendigorría (July 16, 1835) - Liberal victory

- Battle of Arlabán (January 16–18, 1836) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Terapegui (April 26, 1836) - Liberal victory

- Battle of Villarrobledo (September 20, 1836) - Liberal victory

- Battle of Majaceite (November 23, 1836) - Liberal victory

- Battle of Luchana (December 24, 1836) - Liberal victory

- Battle of Oriamendi (March 16, 1837) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Huesca (May 24, 1837) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Villar de los Navarros (August 24, 1837) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Andoain (September 14, 1837) - Carlist victory - End of the British Auxiliary Legion as an effective fighting force

- Battle of Aranzueque (September 19, 1837) - Liberal victory, end of Carlist campaign known as the Expedición Real

- Battle of Maella (October 1, 1838) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Peñacerrada (June 20–22, 1838) - Liberal victory

- Battle of Ramales (May 13, 1839) - Liberal victory

References

- ↑ Bullón de Mendoza y Gómez de Valugera, Alfonso (1992). La primera Guerra Carlista. Madrid. pp. 3–7. ISBN 8487863086.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Bullón de Mendoza y Gómez de Valugera, Alfonso (2019). "La Primera Guerra Carlista en el tomo IV de la Historia militar de España: un error de enfoque". Aportes. XXXIV (100): 288. ISSN 0213-5868.

- ↑ La partida de Palillos y su estandarte, 1833-1840

- ↑ Partidas carlistas y bandidos en el Marmolejo del siglo XIX

- ↑ López-Morell, Miguel A. 2015, p. 45

- ↑ López-Morell, Miguel A. 2015, pp. 51, 63

- ↑ since at the beginning of the 18th century, Philip V, the first Bourbon king of Spain, had promulgated the Salic Law, which barred the Spanish crown to women. His purpose was to thwart the Habsburgs' regaining the throne by way of the female dynastic line.

- 1 2 Butler Clarke 1906, p. 91.

- ↑ Butler Clarke 1906, p. 92.

- ↑ López-Morell, Miguel Á. (2015). Rothschild; Una historia de poder e influencia en España. Madrid: MARCIAL PONS, EDICIONES DE HISTORIA, S.A. pp. 56–57, 61. ISBN 978-84-15963-59-2.

- ↑ López-Morell, Miguel A. 2015, p. 62

- ↑ Butler Clarke 1906, p. 94.

- ↑ López-Morell, Miguel A. 2015, p. 62-63

- ↑ Bradley Smith, Spain: A History in Art (Gemini-Smith, Inc., 1979), 259.

- ↑ "Evenings at Sea," Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 48, July–December 1840 (T. Cadell and W. Davis, 1840), 42.

- ↑ Kepa Oliden (19 April 2009). "Mondragón y la Gipuzkoa española". El Diario Vasco. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ↑ John Francis Bacon, quoted in Santiago, Leoné (2008). "Before and after the Carlist war: Changing images of the Basques" (PDF). RIEV (Revista Internacional de Estudios Vascos. EuskoMedia Fundazioa. 2: 59. ISBN 978-84-8419-152-0. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Stephens, Edward.B. 1837 (1), p. 15

- ↑ Esparza Zabalegi, Jose Mari (2012). Euskal Herria Kartografian eta Testigantza Historikoetan. Euskal Editorea SL. p. 94. ISBN 978-84-936037-9-3.

- ↑ Crocker&Barker (1838), quoted in Santiago, Leoné (2008). "Before and after the Carlist war: Changing images of the Basques" (PDF). RIEV (Revista Internacional de Estudios Vascos. EuskoMedia Fundazioa. 2: 59. ISBN 978-84-8419-152-0. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Cayuela Fernández, José (2006). "Los marinos vascos en Trafalgar" (PDF). Itsas Memoria.Revista de Estudios Marítimos del País Vasco. Untzi Museoa/Museo Naval (5): 415, 431. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ↑ Paul Johnson, The Birth of the Modern World: Society 1815-1830 (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), 660.

- ↑ "A Night Excursion with Martin Zurbano", Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 48, July–December 1840 (T. Cadell and W. Davis, 1840), 740.

- 1 2 19th Century bibliography of military history in the Basque Country

- ↑ Charles William Thompson, Twelve Months in the British Legion, by an Officer of the Ninth Regiment (Oxford University, 1836), 129.

- ↑ Henry Bill, The History of the World (1854), 142.

- ↑ Zumalacárregui y el Independentismo vasco

- ↑ T. M. Hughes, Revelations of Spain in 1845 (London: Henry Colburn, 1845), 124.

Further reading

- Butler Clarke, H. (1906). Modern Spain 1815-1898. Vol. 2.

- Lawrence, Mark. Spain’s First Carlist War, 1833-40. Palgrave: Basingstoke, 2014.

- Atkinson, William C. A History of Spain and Portugal. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1960.

- Brett, Edward M. The British Auxiliary Legion in the First Carlist War 1835-1838: A Forgotten Army. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2005.

- Carr, Raymond. Spain, 1808-1975 (1982), pp 184–95

- Chambers, James. Palmerston: The People's Darling. London: John Murray, 2004.

- Clarke, Henry Butler. Modern Spain, 1815-98 (1906) old but full of factual detail online

- Coverdale, John F. The Basque Phase of Spain's First Carlist War. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Holt, Edgar. The Carlist Wars in Spain. Chester Springs (Pennsylvania): Dufour Editions, 1967.

- Payne, Stanley G. History of Spain and Portugal: v. 2 (1973) ch 19-21

- Webster, Charles K. The Foreign Policy of Palmerston 1830-1841. London: E. Bell & Sons, 1951. (2 volumes).

- Wellard, James. The French Foreign Legion. London: George Rainbird Ltd., 1974.

- Williams, Mark. The Story of Spain. Puebla Lucia (California): Mirador Publications, 1992.

In Spanish

- Alcala, Cesar and Dalmau, Ferrer A. 1a. Guerra Carlista. El Sitio de Bilbao. La Expedición Real (1835-1837). Madrid : Almena Ediciones, 2006.

- Artola, Miguel. La España de Fernando VII. Madrid: Editorial Espasa-Calpe, 1999.

- Burdiel, Isabel. Isabel II. Madrid: Santillana Ediciones, 2010.

- Bullón de Mendoza, Alfonso. La Primera Guerra Carlista. Madrid: Editorial Actas, 1992.

- Bullón de Mendoza, Alfonso (Editor): Las Guerras Carlistas. Catálogo de la exposición celebrada por el Ministerio de Cultura en el Museo de la Ciudad de Madrid. Madrid, Ministerio de Cultura, 2004.

- Clemente, Josep Carles. La Otra Dinastía: Los Reyes Carlistas en la España Contemporanea. Madrid: A. Machado Libros S.A., 2006.

- Condado, Emilio. La Intervención Francesa en España (1835-1839). Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos, 2002.

- De Porras y Rodríguez de León, Gonzalo. La Expedición de Rodil y las Legiones Extranjeras en la Primera Guerra Carlista. Madrid: Ministerio de *Defensa, 2004.

- De Porras y Rodríguez de León, Gonzalo. Dos Intervenciones Militares Hispano-Portuguesas en las Guerras Civiles del Siglo XIX. Madrid: Ministerio de Defensa, 2001.

- Fernandez Bastarreche, Fernando. Los Espadones Románticos. Madrid: Edito-rial Synthesis, 2007.

- Garcia Bravo, Alberto; Salgado Fuentes, Carlos Javier. El Carlismo: 175 Años de Sufrida Represión. Madrid: Ediciones Arcos, 2008.

- Henningsen, Charles Frederick. Zumalacarregui. Buenos Aires: Espasa-Calpe Argentina, 1947.

- Moral Roncal, Antonio Manuel. Los Carlistas. Madrid: Arco Libros, 2002.

- Moral Roncal, Antonio Manuel. Las Guerras Carlistas. Madrid: Silex Ediciones, 2006.

- Nieto, Alejandro. Los Primeros Pasos del Estado Constitucional: Historia Administrativa de la Regencia de Maria Cristina. Barcelona: Editorial Ariel, 2006.

- Oyarzun, Roman. Historia del Carlismo. Madrid: Ediciones Fe, 1939.

- Perez Garzon, Juan Sisinio (Editor). Isabel II: Los Espejos de la Reina. Madrid: Marcial Pons Historia, 2004.

- Pirala, Antonio. Historia de la Guerra Civil. Madrid: Turner SA / Historia 16, 1984. (6 Volumes).

- Romanones, Conde de. Espartero: El General del Pueblo. Madrid: Ikusager Ediciones, 2007.

- Urcelay Alonso, Javier. Cabrera: el Tigre del Maestrazgo. Madrid: Ariel, 2006.

- Vidal Delgado, Rafael. Entre Logroño y Luchana: Campañas del General Espartero. Logroño (Spain): Instituto de Estudios Riojanos, 2004.

In Portuguese

- J.B. (Full name unknown). "Relaçao Historica da Campanha de Portugal pelo Exercito Espanhol as Ordens do Tenente General D. Jose Ramon Rodil (1835)". Published as part of D. Miguel e o Fim da Guerra Civil: Testemunhos. Lisbon: Caleidoscopio Edição, 2006.

In French

- Montagnon, Pierre. Histoire de la Legion. Paris: Pygmalion, 1999.

- Porch, Douglas. La Legion Etrangere 1831-1962. Paris: Fayard, 1994.

- Bergot, Erwan. La Legion. Paris: Ballard, 1972.

- Dembowski, Karol. Deux Ans en Espagne et en Portugal, pendant la Guerre Civile, 1838-1840. Paris: Charles Gosselin, 1841.

External links

- Chronology of the First Carlist War

- Site by the Zumalakarregi Museum dedicated to the First Carlist War

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)