The functions of the Pharaoh are the various religious and governmental activities performed by the king of Egypt during Antiquity (between the years 3150 and 30 BC). As a central figure of the state, the pharaoh is the obligatory intermediary between the gods and humans. To the former, they ensured the proper performance of rituals in the temples; to the latter, they guaranteed agricultural prosperity, the defense of the territory and impartial justice.

In the sanctuaries, the image of the sovereign is omnipresent through parietal scenes and statues. In this iconography, the pharaoh is invariably represented as the equal of the gods. In the religious speech, they are however only their humble servant, a zealous servant who makes multiple offerings. This piety expresses the hope of a just return of service. Filled with goods, the gods must favorably activate the forces of nature for a common benefit to all Egyptians. The only human being admitted to dialogue with the gods on an equal level, Pharaoh is the supreme officiant; the first of the priests of the country. More widely, the pharaonic gesture covers all the fields of activity of the collective and ignores the separation of powers. Also, every member of the administration acts only in the name of the royal person, by delegation of power.

From the Pyramid Texts, the political actions of the sovereign are framed by a single maxim: "Bring Maat and repel Isfet", that is to say, promote harmony and repel chaos. As the nurturing father of the people, Pharaoh ensures prosperity by calling upon the gods to regulate the waters of the Nile, by opening the granaries in case of famine and by guaranteeing a good distribution of arable land. Chief of the armies, the pharaoh is the brave protector of the borders. Like Ra who fights the serpent Apophis, the king of Egypt repels the plunderers of the desert, fights the invading armies and defeats the internal rebels. Pharaoh is always the sole victor; standing up and knocking out a bunch of prisoners or shooting arrows from his battle chariot. As the only legislator, the laws and decrees he promulgates are inspired by divine wisdom. This legislation, kept in the archives and placed under the responsibility of the vizier, applies to all, for the common good and social agreement.

Origins

Archaeological evidence

At no time between 3150 and 30 BCE were the institutions of the Pharaonic monarchy framed by a charter or a constitutional text. There is therefore no reason to look for a corpus of fundamental laws framing the governmental, military and religious functions exercised by the king of Egypt. During these 3,000 years, the character of Pharaoh was inseparable from the Egyptian state. Even in the midst of the worst political vicissitudes - the periods between the great Empires - the royal prestige remained intact.[1]

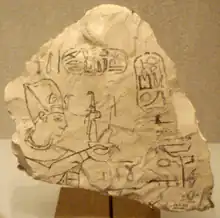

The central place of the ruler in society is attested by numerous and varied archaeological sources. As early as the Predynastic period, the king is shown in the exercise of his essential functions: cult to the gods, agrarian rites and warlike activities. Among the most ancient documents, the Scorpion Macehead (about -3100) found at Nekhen can be mentioned. The king is shown with a hoe in his hands and preparing to perform a digging rite.[2] On the same archaeological site, a series of cosmetic palettes was also discovered. The most famous of these is the Narmer Palette, famous for its warlike depiction of the king shown standing and brandishing a club, ready to smash the skull of a kneeling enemy.[3] The documentation on papyrus archived by the scribes has almost entirely disappeared. A few ostraca have better resisted time. However, some major witnesses have survived. Such is the case of the Abusir Papyri, which is a collection of inventories, lists and decrees dating from the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties.[4] Such is also the case of the Harris Papyrus, which is a summary of the numerous royal actions and donations made during the lifetime of Ramesses III in the Twentieth Dynasty.[5] Pharaonic power was naturally manifested in the funerary architecture of the necropolises of Giza, Saqqara and the Valley of the Kings. The Pyramid Texts, while being funerary writings, are also an exposition of the royal ideology where the pharaonic office is magnified and divinized.[6] The temples are the other witnesses of the royal activities with the numerous scenes of offerings to the gods but also the warlike exploits narrated by the sovereigns of the New Kingdom like Thutmose III (battle of Megiddo) and Ramesses II (Battle of Qadesh). In general, the pharaonic functions and activities are attested by an impressive quantity of documents inscribed on steles, on statues, in tombs, in stone quarries, along roads, on places of passage, etc.[7]

The royal schedule

Egyptian sources have not been concerned with describing the daily schedule of the pharaoh. Rather, they tend to magnify the ruler and contextualize their actions in a mythological framework. The description given by the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus in his Bibliotheca historica (Book I, 70-71), although detailed, was done too late - at the end of the Ptolemaic period - to be taken without reservation. Some elements of plausibility are, however, undeniable. The study of the aulic titles worn by courtiers such as "director of the king's linen", "diadem attendant" or "chief of the hairdressers" demonstrate the importance given to the king's rising. Everything in the official phraseology indicates that the royal palace is assimilated to the celestial domain and that the pharaoh evolves there like Ra, the solar star. The dietary abstinence of the king must probably be related to the observance of taboos. The Nubian pharaoh Piye thus refuses to receive men considered impure in their presence because "they were uncircumcised and ate fish[8]".

"(70) First of all, the kings did not lead such a free and independent life as those of other nations. They could not do as they pleased. Everything was regulated by laws, not only their public life, but also their private and daily life. (...) The hours of the day and night, at which the king had some duty to perform, were fixed by laws, and were not left to their arbitrariness. Awakened in the morning, they had first to receive the letters that were sent to them from all parts, in order to take an exact knowledge of all that was happening in the kingdom, and to regulate their acts accordingly. Then, after having bathed and dressed in the insignia of royalty and magnificent clothes, they offered a sacrifice to the gods (...) There was a fixed time, not only for hearings and judgments, but also for walking, for bathing, for living together, in a word, for all the acts of life. The kings were accustomed to live on simple food, on the flesh of calves and geese; they were not to drink more than a certain measure of wine, fixed in such a way as to produce neither too much fullness nor drunkenness (...) (71) It seems strange that a king should not have the freedom to choose their daily food; and it is still stranger that they should not be able to pronounce a judgment, nor to make a decision, nor to punish anyone, either from passion or from caprice, or from any other unjust reason, but that they should be forced to act in accordance with the laws laid down for each particular case. (...) Animated by such sentiments of justice, the rulers conciliated the affection of their people like that of a family (...) All the kings mentioned preserved this political regime for a very long time, and they led a happy life under the empire of these laws; moreover, they subdued many nations, acquired very great wealth and adorned the country with extraordinary works and constructions, and the cities with rich and varied ornaments."

— Diodorus Siculus, Bibliothèque historique, Book I 70-71 (excerpts).[9]

Teachings

From the 21st century onwards, Egyptian ethics are expressed in wisdom texts. These writings contain value judgments and moral rules based on Maat. Good behavior is idealized and deviations are stigmatized.[10] Concerning the pharaonic functions, the "Teaching for Merikare" ("Enseignement pour Mérikarê") is particularly valuable despite its textual gaps. The teaching is addressed by a father to his son, probably the pharaoh Kheti III to his successor Merikare.[11] The historical context is that of the First Intermediate Period. The kingdom was divided and in the grip of civil war. In the north, the rulers of the Tenth Dynasty of Heracleopolis were installed, while in the south, those of the Eleventh Dynasty of Thebes were evolving. The various pieces of advice addressed to the future pharaoh are presented as a treaty on monarchy. The art of governing is presented in a general way: to reduce the factious, to constitute a powerful army, the virtue of the word and the example, the need to have a long-term vision, respect of the intimates and the notables, the need for a fair justice. All these actions are part of the political situation of the moment which is that of a period of unrest. The teaching is however also presented as an analysis of the royal function. It is not an enthusiastic and excessive praise where the pharaoh is hoisted in the world of the gods. On the contrary, in a pessimistic way, the king is presented as a lonely man, not even assured of being able to transmit his office to his son. Pharaoh Khety admits to being a mere mortal, capable of mistakes and failures. Unceasingly, he must give an account to the gods who observe him and punish him. A bad action is either sanctioned by another through a backlash, or sanctioned by Osiris in the afterlife during the judgment of the soul.[12]

Priestly function

Egyptian temple

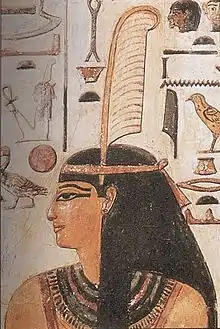

The Egyptian temple is a sacred place forbidden to the crowd. The Egyptian term Hout-Netjer, which can be translated as "Abode of the god", indicates that it is a place destined to welcome on earth a part of the divine eternity. It is not a place of gathering where an assembly of believers communes in the same faith. This aspect is not, however, totally evacuated. In rare exceptions, during some annual festivities, devotees are allowed to walk on the floor of the inner courtyards. Sheltered in the naos, in the depths of the sanctuary, the divine statue concentrates within it the mystery of the cosmic forces at work in the universe. At set times, the Hem-Netjer (or "Servants of the God", i.e. the priests) provide the statue with precise domestic care. Hymns are sung to wake her up, she receives clothes and ornaments. Its strength is maintained by several daily meals.[13] In theory, Pharaoh is the only one authorized to approach the statue. In fact, physically absent, they are replaced by the priests, their substitutes. Pharaoh is, however, omnipresent through their image.[14] The entire decoration of the walls is devoted to his encounter with the deity. From the entrance pylons, he pays homage to the gods by offering them kneeling prisoners that he knocks out with his club. On the outer walls, warlike scenes show the royal exploits during battles. Standing in his chariot, Pharaoh shoots deadly arrows while his proud horses trample and rout the enemy forces. With this gesture, the tranquility of the country is assured in the face of external chaos. On the inner walls, the intimacy with the gods is total. Pharaoh is embraced, kissed and invigorated by his divine equals. Elsewhere, more humbly, he stands or kneels and performs the necessary libations, fumigations and purifications before the gods. Multiple gestures of offering are performed. Drinks, food, ornaments, ointments and minerals are brought in order to maintain the divine forces that ensure the prosperity of the country.[15]

Servant of the gods

In the Egyptian texts, the royal person is often designated by the title of hem. Egyptologists, steeped in European monarchical philosophy, generally translate this ancient term by the word "Majesty" which comes from the Latin magnitas, "greatness". This translation is, however, not precise. The hieroglyphic writing renders the word hem by the image of the beater or whitener's stick, an utensil used to beat the linen in order to soften it and to eliminate the last impurities. In the Egyptian lexicon, the word hem is thus not associated with greatness but is linked to the notion of service: hem / hemet (servant / maid) and hemou (launderer). In the Satire of the Trades, the laundering of linen is presented as the most impure of labors because of its contact with the menstrual blood of women.

Since its rediscovery in the nineteenth century, the story has been seen as a source of inspiration for biblical authors (Joseph and the wife of Potiphar). However, the text also has structural similarities with the founding myths of the Shilluk and Anuak peoples of the Upper Nile. The episode of Razzia de Nyikang au Pays du Soleil (theft of cows and women) is quite similar to the military expedition that Pharaoh mounts against Bata in Pays du Pin parasol (a place frequented by Ra) in order to steal his companion from him. At the enthronement of the Shilluk kings, the prince destined to ascend the throne is first captured by dignitaries and symbolically enslaved by the words "You are our Dinka servant". The word netjer (god) is associated with hem-netjer, which means "priest" and, more literally, "servant of the god".[16][17][18]

According to the texts engraved on the walls of the temples, Pharaoh places himself with fervor and sincerity under the dependence of the gods. To show his gratitude to Amun, king Thutmose I says very humbly: "I kiss the ground before your majesty ". A Ramesside ruler, approaching the same god, declares: "... lying on the ground, I kiss the ground for your august figure ". These words of humility correspond to real postures and real cult gestures. As early as the Fourth Dynasty, royal statuary shows Pharaoh in servile attitudes. The ruler is shown kneeling with ritual objects in his hands or raising them in a gesture of offering and adoration. This submission has as a corollary obedience. In the textual sources, the words "order" and "command" come up constantly. Pharaoh must apply the orders received by the gods. Before Amun, Thutmose III says: "I am not negligent about what you have ordered to be done... I do it according to his order". These divine orders cover all the fields of the possible: to build or renovate a temple, to mount a military expedition to the borders, to erect a pair of obelisks, to dig a well in the desert, etc. This obedience results from a link of kinship, Pharaoh being the son of the gods and goddesses. Without being exhaustive, in the Harris Papyrus, Ramesses III says he is the son of Amun, Atum, Ptah, Thoth, Osiris, and Wepwawet. Each deity can be considered as the father or the mother of Pharaoh. These relationships of subordination of the son to his parents entail duties and obligations. The gods have placed Pharaoh on the throne; in exchange, he must put himself at their service if he wants to hope for a long and prosperous reign.[19]

Servant of the cult

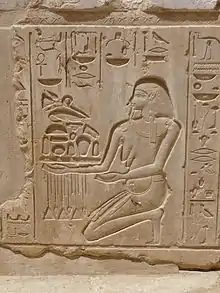

On the walls of the temples, in the cult scenes, Pharaoh is the exclusive interlocutor of the gods. Episodically, the wives, royal sons and daughters, but also the priests and dignitaries have the right to appear as a substitute. The biological rhythm of the deities is modelled on that of humans, with its alternation of sleep and wakefulness; in addition, they need to feed themselves. Pharaoh's role is to maintain this divine vitality. All the wealth, all the clothes, all the food that converge towards the temple and its warehouses are a contractual duty between the gods and the humans, but Pharaoh is the only guarantor and responsible for it. The choice, the quantity and the frequency of the offerings depend on the god to whom the temple is dedicated. Each god has their religious or geographical specificity. Khnum, the god of the flood, receives water; Geb, the god of the earth, receives bouquets of flowers; Min, who protects commercial and mining expeditions, receives frankincense and myrrh; Thoth, the chief scribe, receives writing materials; goddesses are offered necklaces, sistra, and mirrors, etc. The offerings are generally easily recognizable, and their iconography has changed little over the ages. Few differences can be discerned between the New Kingdom scenes engraved at Karnak or Abydos and those of the Greco-Roman period at Philæ, Edfu, Dendera, even though there is a 1,500-year gap between them. The decoration of the Ptolemaic temples is however much more prolix. The temple of Edfu alone has 1,800 such scenes. For each gift, Pharaoh expects a beneficial counter-gift to their people. With food offerings, they obtain fertility and fecundity, with drinks joy and drunkenness, with water a consequent flood, with milk milk, with crowns a long and prosperous reign, with precious stones mining products in quantity.[20]

Offering of the Maat

According to the myth of the Heavenly Cow, in the beginning, gods and men constitute a single community presided over by Ra the creator god. After a human revolt, Ra decimated the human population and withdrew into the sky on the back of Nut, who was transformed into a gigantic cow. Since then, from the highest heaven, Ra presides over the phenomena of the cosmic cycles. On earth, Pharaoh is mandated by Ra to fulfill a substitute role. Charged with continuing the beneficial work of the creator, Pharaoh establishes the general welfare by realizing Maat and driving out the disorder-isfet. As a referential concept, Maat allows Pharaoh to maintain intimate contact with the divine forces at work on earth from heaven. According to the Coffin Texts (chapters 75-83) n. 2 , at the beginning of time, the creator-god Atum became aware of himself during a dialogue with Nun, the primordial ocean:

"Breathe in your daughter Maat, put her to your nose so that your heart lives! Let them not go away from you, your daughter Maat and your son Chou who is called Life! Thus you will feed on your daughter Maat, and it is your son Chou who will raise you."

— Words of the Nun to Atum, Textes des sarcophages, chap. 80 (excerpt). Translation by Paul Barguet[21]

In this allegorical text, Shu and Tefnut, the two twin children of Tem, are Life and Maat. All three form a consubstantial unity. Without the created Universe, Life and Maat cannot exist and without Life and Maat, the Universe cannot be created. On the earthly plane, in his nurturing role, Pharaoh is the one who institutes life. He is the one who organizes the agriculture and the breeding by guaranteeing the good distribution of the lands. On the wastelands, he found vast and prosperous agricultural domains. In order to have good harvests, he performs in the temples agrarian rites in honor of the gods of fertility. The Maat is the set of positive forces that make this system work.[22] In temple iconography, the offering of Maat is a scene that shows Pharaoh holding out a basket with Maat sitting on it to a deity. By this gesture, Pharaoh triggers the divine cycles that ensure life. By offering the earthly Maat as food, he shows the deity to whom he is addressing that he is capable of organizing the general welfare. In return for this gift, undoubtedly the most precious of all, Pharaoh obtains from the gods that the system endures by sending the cosmic Maat that are the cycles of time and seasons.[23]

"Words to say: I have come to you; I am Thoth, the two hands joined to carry Maat. Hail to you! Amon-Ra, this august god, master of eternity (...) Maat has come, so that she is with you; Maat is in every place that is yours, so that you rest on her; behold, the circles of the sky appear towards you; their two arms adore you every day. It is you who gave the breaths to every nose to vivify what was created with your two arms (...) Hail to you! Provide yourself with Maat, author of what exists, creator of what is. It is you, the good god, the beloved; your rest is when the gods make you the offering. You go up with Maat, you live of Maat, you join your limbs to Maat, you give that Maat rests on your head, that she makes her seat on your forehead. Your daughter Maat, you rejuvenate at the sight of her, you live of the perfume of her dew; Maat puts herself like an amulet on your neck, she rests on your chest; the gods pay you their tributes with Maat, because they know her wisdom. Here come the gods and the goddesses who are with you wearing Maat, they know that you live from her; your right eye is Maat, your left eye is Maat, your flesh and your limbs are Maat (...) ".

— Rituel du culte divin journalier. Chapter of giving Maat (extracts). Translated by Alexandre Moret[24]

Conjuring of calamities

The Egyptian goddesses are by nature bipolar powers, both terrible and gentle. Each of them has come to embody the female principle of Ra, the solar god. All of them are assimilated to the Eye of Ra, namely the Uraeus placed on the forehead of the gods and pharaohs. When these goddesses are under control, their power is life-giving. In fury, they unleash their devastating anger on the Egyptian land. The most terrible of these goddesses is the lioness Sekhmet, whose name means "The Mighty One". In the Book of the Heavenly Cow, the lioness embodies the aspect of Hathor sent by Ra to decimate the humans in revolt against him. Having acquired a taste for blood, the goddess is unable to restrain herself. To calm her fury, Ra invents beer and gets her drunk to put her to sleep. In the exercise of his office, Pharaoh has to ward off the anger of Sekhmet and her envoys. According to the belief, the goddess' anger is shown especially at times of transition when the cosmic cycles must find their balance (change of day, decade, month, year). The most dreaded moment is the New Year, during the five epagomenal days that precede it, just before the arrival of the flood. It is up to Pharaoh to make use of the power of the furious goddess - against the outside world - or to appease her by offering. The best known ritual is the Sehotep Sekhmet or "Appeasement of Sekhmet", performed in the New Year. For each month of the year there is a hymn. Throughout, the power of the goddess is exalted and Pharaoh begs her to calm down. During the offering of the sistrum, Sekhmet is invited to become the gentle Bastet, the cat goddess.[25] Sekhmet's fury was particularly feared by King Amenhotep III (Eighteenth Dynasty). He had several hundred statues carved. Nearly six hundred, more or less damaged, are known to this day. It is not impossible to think that the total amounted to 720 (= 360 x 2), that is to say a statue for each half-day of the Egyptian calendar. These statues were undoubtedly installed in his mortuary temple located in the Western Theban. But they were scattered throughout the country very early on, from the reign of Ramesses II. According to the Egyptologist Jean Yoyotte, this vast statuary ensemble is to be considered as an invocation to the appeasement of Sekhmet.[26][27]

"Hail to you, Sekhmet, in these perfect names of hers! The King of Upper and Lower Egypt comes to you because he is Ra. Save him from the slaughtering geniuses, from the emissaries who rush after you, let them not have a hold on him. Keep away your wanderers who shoot every evil arrow, every evil contagion, so that no evil breath, no pernicious passerby, no evil attack, etc., of this year can destroy him. The Son of Ra is in a cradle of life, he lives among the living who are yours!"

— The Ritual of the Sehotep Sekmet (extract). Translation by J.-Cl. Goyon.[28]

Nurturing function

Flooding of the Nile

An agricultural society surrounded by desert, ancient Egypt based its prosperity on the waters of the Nile. The annual regime of the river is marked by two extremes: high water and low water, which are constantly repeated. If the flood is an impressive phenomenon, it is rarely devastating. Throughout history, cultivation and irrigation techniques have remained rudimentary but effective, due to skilful management (consolidation of dikes, digging of flood basins, cleaning of canals). Every year, at the height of the June heat, the flood is awaited with feverish impatience. With fatalism, a good level of flooding is hoped for. If the water level is too low, it means insufficient harvests, announcing famine or starvation. Conversely, too high a water level would break the retaining structures and engulf the most exposed dwellings.[29] In the Egyptian system of thought, the level of the flood depends on the goodwill of the deities: Horus, Khnum, Amun, Osiris, Ptah, etc. In itself, the flood is deified in the form of Hapi, the god of the Nile. The Egyptians never imagined that Pharaoh was capable of commanding, like a god, the phenomenon of the flood. Their role is lesser and is limited to obtaining the benevolence of the deities, the regularity and abundance of the waters being ensured by means of cult offerings. The cooperation between Pharaoh and the gods is a question of mutual survival. Within the temples, the supply of the altars depends on the flood, and the flood is granted only on the condition of regular and generous service.[30] In the hymns to the gods, Pharaoh's speech does not fail to recall this obvious fact:

"You will give me a high and abundant flood to provide for your divine offerings and to provide for the divine offerings of the gods and goddesses, rulers of Upper and Lower Egypt, to give life to the sacred bulls, to give life to all the people of your land, their cattle and their trees that your hand has created."

The maintenance of the dikes and irrigation canals is not the direct responsibility of Pharaoh, this task falling to the local communities and nomarchs. Nevertheless, the control of the agricultural landscape inspired metaphorical comparisons in which the Egyptian ruler is described as a "stone dike" or a "canal that damps the river against the flow of water". The royal power was never totally disinterested in hydraulic works. On the Scorpion Macehead, the pharaoh is shown digging a system of canals. According to Herodotus, King Menes diverted the course of the Nile to found Memphis. During the Old Kingdom, basins and landing stages were built to transport the building materials for the pyramids. During the Middle Kingdom, in the west, the agricultural region of Faiyum was developed by the canalization of Bahr Yusuf. In the Late Period, to the east, the Pharaohs' Canal provided a link between the Nile and the Red Sea.[32]

Guarantor of the fertility of the land

Affiliated to the gods, Pharaoh is the guarantor of the fertility of the land and the fecundity of the herds. The general well-being of the population is, among other things, ensured by the implementation of annual festive rituals intended to bring about agricultural prosperity before the land is put to cultivation. When the flood waters rise, Pharaoh conducts rituals in which the fertilizing power of Hapi is encouraged by offerings thrown into the river: bread, cakes, flowers, fruits, statuettes in the image of the god. As the supreme priest, they can also order additional sacrifices if the flood is deemed insufficient. These traditions have endured in Muslim Egypt; Bonaparte and his troops witnessed them in 1798 in Cairo. It is of course impossible to ensure the actual presence of Pharaoh at all the annual ceremonies. Thutmose III made an appearance at Thebes, during the Opet Festival, only in the first year of his reign. Generally speaking, a symbolic patronage is sufficient by the image of the sovereign in the wall decoration of the temples. The rising waters can also be the pretext for prestigious royal outings outside the capital. Pharaoh waits for the coming of the high waters in the southernmost region (Ist nome of Upper Egypt), then goes downstream by traveling by boat on the Nile in a course punctuated by multiple provincial stages, with celebrations in the local temples. Thus Ramesses II or Ramesses III are present at Gebel Silsileh to attend the appearance of the flood. Much later, Ptolemy IX went to Elephantine for the same reason. Failing to be able to attend a celebration in person, Pharaoh can send a delegate with sumptuous means.[33]

Royal providence

As early as the Old Kingdom, famines are mentioned. At Saqqara, on the rising pavement of the funerary temple of Unas (Fifth Dynasty), famished Bedouins, emaciated and with protruding ribs, are shown coming to Egypt in search of some food. During the First Intermediate Period, an inscription left by a nomarch mentions cases of human cannibalism in times of famine, a statement taken up in the first century B.C. by the Roman historian Diodorus Siculus: "It is said that the inhabitants of Egypt, being one day in the grip of famine, devoured each other without touching the sacred animals." (Bibliotheca historica, Book I-84).[34] It is highly probable that the reasons for the dislocation of the Old Kingdom and the decline of the New Kingdom are to be found in the inability of the Pharaonic power to curb the dramatic consequences of the bad Nilotic floods. The drying up of harvests led to shortages and the weakening of the inhabitants, social injustice increased with the growing corruption and prevarication of the elites, while insecurity spread in the countryside through the banditry of the starving thrown onto the roads.[35]

Learning from the troubled years of the First Intermediate Period, the pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom enriched the ideological discourse with the theme of abundance and redistribution of food. Royal providence is presented as the exact opposite of the calamities of famine. By ordering the opening of the stores, Pharaoh ends poverty and, like a supernatural power, ensures general abundance. In the Instructions of Amenemhat, the ruler Amenemhat I assures his son Sesostris I that his reign was beneficial for the people: "I am one who created barley, to which Nepri marked his predilection. Since Hapi showed me solicitude in every open space, there was no hunger during my years, nor was there any thirst ".[36] The nurturing qualities of the pharaoh are taken up again in the New Kingdom. In the Nineteenth Dynasty, Pharaoh Seti I was "the one who fills the stores, enlarges the granaries, and gives goods to the one who is deprived of them". His successor Ramesses II presents himself as "the one who allows the young generations to grow by enabling them to live" by the miraculous increase of food rations. Under Ramesses II II, but already under Akhenaten (Eighteenth Dynasty), the pharaonic action is assimilated to the fertilizing power of the river through panegyrics where Pharaoh endorses for his own account all the benefits granted by Hapi and praised until then in the Hymns to the Nile. In the statuary, the pharaoh Amenemhat III (Twelfth Dynasty) is the first to be represented as a carrier of offerings, his arms supporting a table loaded with fish and aquatic plants. This theme was later taken up by Thutmose III (Eighteenth Dynasty) and Sheshonq I (Twenty-second Dynasty).[37]

Devolution of the land

Mandated by the gods, Pharaoh is the sole owner of the Egyptian soil. This divine heritage is, in fact, indivisible because no pharaoh is authorized to sell a cultivable plot of land to a third party, or to negotiate with a foreign power the transfer of a part of the territory. Throughout history, pharaohs were only allowed to engage in two actions: the first is to found new domains on virgin or fallow lands, the second is the devolution of agricultural lands, i.e. the concession to a third party of rights and revenues attached to a cultivated land. A foundation and a grant may be combined or dissociated according to the purposes sought; a grant may result from a new foundation and a foundation may result from the transfer of new rights over an already existing base.[38]

By written acts duly recorded and preserved in the palatial archives, Pharaoh delegates their property, on a temporary or permanent basis, to the divine temples, to their administrators and to deserving individuals (courtiers, soldiers) in order to support their families and to finance their funerary foundations. From these lands entrusted by the sovereign, the beneficiaries received income in kind because the Egyptian economy was based on barter and on the exchange of services (corvée, contractual work). Thus, the country does not know the currency before the end of the Late Period and the meeting with the Greek world. The direct beneficiaries of land revenues could, in turn, delegate part of their rights over the land. The successive dismemberments do not, however, in any way undermine the respect for the unique and eminent property of Pharaoh because, in reality, only the revenues of the domain are conceded. During periods of weakened central power (the intermediate periods), Pharaoh's sole ownership is close to fiction, but remains the legal framework for the distribution of land.[39] This complex system of dismemberment of Pharaonic property continued without much change until the conquest of Alexander the Great. All the transactions concerning fields that are known to us through archaeology therefore only concern operations on an intangible asset, namely the collection of income from the land (donation, tenure, emphyteusis). This centralized system necessarily includes a large part of redistribution. Agricultural surpluses were levied through taxation and were allocated to various needs (salaries of officials, food rations, divine and funerary offerings). The treasury was also fed by periodic taxes and occasional requisitions on livestock and manufactured goods.[40]

Warrior function

Myth of the original fight

The Egyptian religious imagination is dominated by the myth of the original conflict. The explanations of the origin of the Universe are multiple, but all refer to a fight between a Creator God and an evil Serpent. The different stories draw from the same pattern. A demiurge becomes aware of himself and emerges from the Nun, the original swampy ocean. This liquid mass is, however, haunted by a gigantic serpent that is the incarnation of nothingness. The demiurge takes human (or animal, depending on the version) form and raises a mountain. Immediately, he begins to organize his creation by establishing the luminaries (sun, moon, stars), the divine, human and animal life. Reduced in its possessions, the serpent attacks the created universe. The eternal battle of the Sun against the Serpent then begins. These battles produce a precarious balance between Creation and Chaos.[41] According to the esoteric books of the New Kingdom (Book of the Amdouat, Book of Gates, Book of the Earth) reproduced on the walls of the royal sepulchers, every night, the boat of Ra is attacked by the serpent Apophis. The greatest danger for Ra is to see his boat finally run aground on a sandbank. However, a harpooner god (Seth, Horus or Horouyfy) who does not hesitate to pierce the snake ensures a safe crossing to daylight.[42]

In this pessimistic vision of a constantly threatened universe, the common expression "the sandbank of Apophis" is a metaphor that was used by the Egyptians to designate "famine" and, in general, "distress. Now, for this ancient people, with a very global thinking, the mythical, political, social and individual crises refer to each other. So when, in the myth, Ra triumphs over Apophis, on earth, it is Pharaoh who triumphs over all famine, epidemics, rebellion and war. Every night, within the temples and under the aegis of Pharaoh, rituals of bewitchment were therefore performed, intended to bring about the defeat of Apophis, the victory of the cosmic enemy being bound to have harmful repercussions on Egyptian soil:[43]

"If one does not decapitate the enemy that one has in front of him, whether he is modeled in wax, drawn on a blank papyrus, or carved in acacia wood or in wood-hema, according to all the prescriptions of the ritual, the inhabitants of the desert will revolt against Egypt, and there will be a war of rebellion in the whole country; the king will no longer be obeyed in his palace, and the country will be deprived of defenders.

— Papyrus Jumilhac, XVIII, 9-12. Translation by Jacques Vandier.[44]

Fight against the forces of chaos

As guarantor of the Maat on earth, Pharaoh has to quell rebellions, repel invasions and chase away the plunderers who threaten Egypt. In the temples, parietal decorations and commemorative steles record the military exploits of the sovereigns through images and texts. For the New Kingdom alone, the wars of Thutmose I in Nubia and Mitanni,[45] those of his grandson Thutmose III (about fifteen campaigns in Syria-Palestine, including a new incursion into Mitanni),[46] the battle of Qadesh of Ramesses II against the Hittites[47] and the victory of Ramesses III against the Sea Peoples are thus known.[48] For the Ancient Egyptians, military feats are not a matter for history, because this science, with its methods, is unknown to them. For them, the political event is the re-actualization of the myth of the original combat (Ra against Apophis). As the depositary of the energy of the Demiurge (Atum, Ra, Amun, Ptah, etc.), Pharaoh is the one who stops the evil forces. In this perspective, every rebel, invade, and plunderer is a manifestation of the primordial chaos - chaos that Pharaoh must eradicate by his warlike power.[49]

"Long live the perfect god, Montu for millions, mighty as the Son of Nut, who fights on the battlefield, a fearless lion when attacked by myriads in a moment, a great bulwark for his army on the day of battle, whose terror has shattered all countries. Egypt rejoices to have such a ruler, after he has expanded his borders forever. The Asians were defeated, their cities were taken, after he crushed the northern countries. The Libyans have fallen because of the fear he inspires (...) He has defeated the warriors of Uatch-ur and Lower Egypt sleeps at night. Vigilant king with reliable plans, nothing he has said has been interrupted. Foreigners come to him with their children to ask for the breath of life. His war cry is powerful in Nubia, his name spreads the Nine Bows. Babylonia and Hatti come bowing down because of his power (...)".

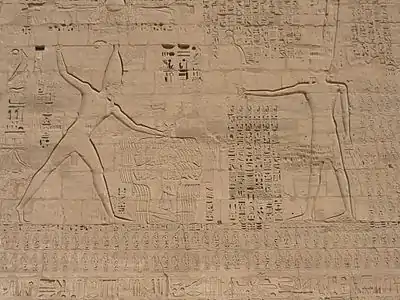

Scene of the Pharaonic triumph

The scene of the "slaughter of the enemy" is a representation of the royal triumph, the reproduction of which continued throughout the three millennia of the Pharaonic civilization. Pharaoh is shown standing, armed with a club and holding a kneeling enemy by the hair. The club is brandished high, ready to smash the skull of a frightened captive, the arms raised in a final defensive gesture or touching the leg of the victor to ask for his mercy and to submit. Some scenes go so far as to multiply the prisoner into a human cluster composed of an indiscernible number of individuals. The first known historical representation appears on the Palette of Narmer dated from the 32nd century. The king is wearing a White Crown and is exercising his omnipotent warrior power under the gaze of the falcon Horus.[51] The origin of this scene, however, is more ancient and finds its origins in prehistory.[52] Numerous examples are attested for the periods known as the Naqada Culture (3800 BC to 300 BC) and show anonymous rulers in the same posture. The oldest known iconographic attestation appears on pottery found in the necropolis of Abydos (Nagada I period).

The massacre of the enemy is an illustration of the first duty of the ruler: the safeguarding of the pharaonic order (Maat) from the assaults of the coalitional powers of disorder (isefet). In some figurations, Pharaoh is holding a group of three enemies. Each of them represents one of the three neighboring peoples of Egypt, a Nubian (south), a Libyan (west) and a Semite (east). Just as the desert is the antithesis of the fertile Nile Valley, these three peoples are seen as the opposite of the Egyptians and their way of life.[53] Pharaoh's triumph is always depicted on temple walls: Ramesses II at Abu Simbel, Ramesses III at Medinet Habu, Ptolemy XII at Edfu. One of the last known representations dates from the colonization of the country by the Roman Empire. A relief from the mammisi of Dendera shows the emperor Trajan in the traditional costume of Pharaoh and with a club in his hand.[54]

- Slaughter of the enemy

Pharaoh Den - First Dynasty - ivory label.

Pharaoh Den - First Dynasty - ivory label._-_Egypt-10C-050.jpg.webp)

Pharaoh on his chariot

The chariot was introduced in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period when the Nile Delta was under the domination of the Hyksos. The latter were chased out of the kingdom by Amasis. From then on, the pharaohs of the Eighteen Dynasty had every opportunity to extend their influence in Syria-Palestine, where they multiplied their military campaigns. The most striking example is Thutmose III who, in twenty years, went on sixteen military expeditions (between the year 23 and 42 of his reign).[55] However, the pharaohs of the New Kingdom did not seek to colonize the Middle East. It was more a question of establishing a zone of influence where the administration remained in the hands of local kinglets, supervised by Egyptian officials and replaced in case of insubordination.

The war chariot played a great role during military operations, it became the new symbol of pharaonic power, both in iconography and phraseology. The first representation of a pharaoh on his chariot goes back to Ahmôsis in a battle scene depicted in his funerary complex of Abydos: the king is standing on his chariot and riddles his enemies with arrows. Historical representations of this kind are relatively few until Thutmose III. Under Ramesses II, they are more numerous at Karnak, Luxor, the Ramesseum and in the Nubian temples. Some scenes relate proven historical facts, such as the variants of the Battle of Qadesh; others are more dubious as to their veracity. The aim is not the search for historical truth but the sublimation of Pharaoh's power in his fight against the forces of chaos. The last great frescoes date back to Ramesses III to relate his campaigns against the Libyans and the Sea Peoples. After him, the chariot scenes are more discreet but are not abandoned and appear on jewelry, chalices or scarabs. A symbol of Egyptian oppression, the image of Pharaoh on his chariot is shattered in the Book of Exodus when the Egyptian chariotry is swallowed up in the sea, a victim of the power of the God of Moses.[56]

Legislative function

Legal and judicial practices

Ancient Egypt is a civilization that did not have professional magistrates. At all levels of society, the function of judging resulted from the administrative authority delegated according to the hierarchical system. A civil servant, whatever his rank, who holds authority over a given territory or service, exercises a judicial power linked to his function. No distinction is made between justice and religion or between criminal and civil law. At the bottom of the ladder, disputes between individuals and routine matters (theft, petty theft, adultery, unpaid bills, neighborhood disputes) are dealt with by the village chief, the site manager or the team leader. The judge tries to discern the truth from the false according to an adversarial procedure between the accuser and the accused with the hearing of witnesses. This is the practice of the palaver, where a mediation solution is attempted in order to ensure social peace. To ensure the veracity of the words of the accused, he must take an oath on the Life of Pharaoh or on the Life of the Gods. To betray this oath is to expose oneself to the death penalty. In the most serious cases, the procedure becomes inquisitorial with the use of torture. This was the case in the Harem Conspiracy where the criminals targeted Ramesses III. The higher up the hierarchy one goes, the more important the trial is and therefore the more the judges are close to Pharaoh: viziers, cupbearers, flabellifiers. In each of the regions, the nomarch represents the supreme authority in judicial matters for cases with a local scope. From the New Kingdom onwards, judges were increasingly recruited from the clergy. In the last instance, the right to judge fell to Pharaoh, especially when it came to applying the death penalty. During the first millennium B.C., legal recourse to the gods through oracular practices was also widely practiced.[57]

The Egyptian state is characterized by an organization based on a vast body of written laws (regulations, jurisprudence, royal edicts, tax exemptions, rental contracts, wills, funerary foundations, endowments, etc.) which, in a court of law, can be presented as evidence of good faith. Every legal act is necessarily formulated in hieroglyphic writing on a papyrus scroll and is kept in an archive. This body of law, however, has not been systematized into a reasoned constitution and codification. Each act finds its supreme reference in the Maat - which is the norm of Truth and Justice - and is placed under the divine patronage of Thoth, the "Master of Laws". According to a legend reported by Diodorus Siculus, this god gave the first laws to Menes, the first pharaoh (Bibliotheca historica, I, 94).[58] Most of this legal corpus is now lost, apart from a few procedures on papyrus and ostraca delivered by the chance of archaeological excavations. The royal edicts considered emblematic of a reign are preserved on the walls of temples or on monumental steles. One of the most famous documents of this kind is the Rosetta Stone, a decree of tax exemptions promulgated by Ptolemy V in favor of the temples of his kingdom.[59]

Pharaonic laws

There is no doubt that Pharaoh is the main initiator of legislation. In general, the apologetic hymns charge him with "strengthening" the laws, "perfecting" them, "promulgating" them and "enforcing" them. The effective functioning of the monarchy is ensured by the laws (hépou) promulgated by means of royal decrees (oudjou nesout; literally, the "orders of the king"). These decrees cover a vast reality of decisions such as announcements of a new reign, letters to officials or courtiers, orders of appointment or dismissal, orders to the administration such as the organization of a military campaign, a mining expedition, the erection of an obelisk or the levying of an exceptional tax. The sovereign could also decide to favour a temple by endowing it with additional land, servants and livestock or even to order its embellishment, renovation or complete reconstruction. The decrees also concern the organization of the funerary cult of his close courtiers through the donation of a sarcophagus, a mastaba or an agricultural foundation intended for the production of food offerings. Thus, it appears that the decrees have either a general scope, such as the improvement of sanitary conditions, or a particular scope, such as the tax exemption of a single domain. The composition of the decrees calls for royal discernment after discussion and consultation with notables and courtiers, but also through consultation of archival writings.[60] Among the many royal decrees listed by egyptologists is the Edict of Horemheb. Dated at the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty, it is intended to reorganize a High Administration corrupted by the negligence of the Amarna episode of Akhenaten. To do this, Horemheb appoints men of confidence, abolishes the taxes most likely to be embezzled, orders the death penalty for corrupt judges, etc. In order to give a character of eternity to this reforming will, the decree is copied on a high granite stele placed in the precinct of Amun-Re at Karnak:

"He began to establish laws, to make Truth and Justice reign throughout the Two Shores; he rejoices when he embraces the beauty of the goddess. Therefore, His Majesty deliberated with his heart to extend his protection over the whole country (...) to repel evil and destroy falsehood; his plans are an effective refuge to drive out violence. The scribe of His Majesty was brought in; he took a palette and a papyrus scroll and began to write, reproducing all the words of the king, for the king himself dictated the decree [...] a decree sealed with His Majesty, to put an end to the brigandage in the country (...)".

The Tjaty (Pharaoh's vizier)

Second in order of precedence and the most important dignitary of the government, the Tjaty is the closest collaborator of Pharaoh. Since the nineteenth century, the time of the first Egyptologists, this title has been translated by the word "vizier" in reference to Ottoman practices and undoubtedly also influenced by the Orientalist trend then in vogue in Europe. The overwhelming character of the office is indicated by the text of Les Devoirs du vizir engraved in the tomb of Rekhmire, a high figure installed in the vizierate during the reign of Thutmose III. From the New Kingdom (Eighteenth Dynasty), but perhaps already under the Thirteenth Dynasty, the office is doubled and the country counts two viziers: one for Upper Egypt, in Thebes, and a second one for Lower Egypt, in Memphis. By his function, the vizier is the first person in charge of the Administration and plays the role of intermediary between Pharaoh and his people. His duties are multiple, such as harvesting the agricultural resources of the state, supervising regional bodies or ensuring the police surveillance of the Palace.[62]

The tomb of Rekhmire is also notable for its transcription of the Installation of the Vizier text delivered by Thutmesis to his newly promoted vizier. The ruler is fully aware of the unpleasantness of the vizier's function. The official must always satisfy his master, avoid slander, not to harm his kinsmen to the benefit of strangers, to keep away from arrogant and dishonest people, to listen to all grievances to the end, never to get angry and always to keep an impartial judgment. Respect for the Maat is at the heart of this speech, as well as the necessary good practice of Justice within the courts.[63]

"From now on, you will have to watch over the courtroom of the vizier, to monitor everything that is done there, because it is the support of the whole country. You see, being a vizier is not a sweet and pleasant thing, it can even be bitter as gall. The vizier is the copper that protects the gold of his master's house; he doesn't lower his face in front of high officials and judges, and he doesn't make his clients of just anyone. (...) Plaintiffs from the South and the North, from the whole country will come... You will see to it that all things are done in accordance with their right, ensuring justice for every man. (...) You see, it is the safe haven of a judge to act in accordance with the rule, when he responds to what a plaintiff asks. (...) See again, a man remains in his position as long as he acts according to what is indicated to him; all is well with him if he does what he has been told. Do not cease at any time to do justice, whose laws are known. (...) "

— Speech of the Installation (extract). Translation by Claire Lalouette.[64]

Six great legislators

In Greek culture, a legislator is a wise man who, through his charisma and his political and legal skills, manages to solve the most intractable crisis situations. The Athenians Dracon and Solon are the most perfect examples. According to the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, ancient Egypt knew six great lawgiver pharaohs (Bibliotheca historica, Book I, 94-95). These six characters are listed in chronological order and under Greek names: Menes, Sasyches, Sesoosis, Bocchoris, Amasis and Darius. The first of them is Narmer, the first of the human pharaohs, to whom Thoth gave the first laws. The second is probably Shepseskaf of the Fourth Dynasty. The third, Sesoosis, is a legendary figure who combines the features of Sesostris I, Sesostris III and Ramesses II. The fourth is Bakenranef, a Saite pharaoh of the Twenty-fourth Dynasty, the fifth is Amasis II of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty and the last is the Persian emperor Darius I, the ruler of an Egypt that has lost its independence:[65]

"(...) the first who committed men to written laws was Menes, a man remarkable for his greatness of soul, and worthy of being compared to his predecessors. He made it known that these laws, which were to produce so much good, had been given to him by Mercury. (...) The second legislator of Egypt was Sasyches, a man of distinguished mind. To the laws already established he added others, and applied himself particularly to regulate the worship of the gods. He is said to have invented geometry and to have taught the Egyptians the theory of the observation of the stars. The third was Sesoosis, who not only made himself famous by his great exploits, but who introduced in the class of the warriors a military legislation, and regulated all that concerns the war and the armies. The fourth was Bocchoris, a wise and skillful king; to him are due all the laws relating to the exercise of sovereignty, as well as precise rules on contracts and conventions. He showed such sagacity in the judgments he passed that the memory of many of his sentences has been preserved to this day. (...) After Bocchoris, Amasis was still occupied with the laws. He made ordinances on the government of the provinces and the internal administration of the country. (...) Darius, father of Xerxes, is regarded as the sixth legislator of the Egyptians. Having abhorred the conduct of Cambyses, his predecessor, who had desecrated the temples of Egypt, he was careful to show gentleness and respect for religion. He had frequent contacts with the priests of Egypt, and was instructed in theology and in the history recorded in the sacred annals (...) ".

References

- ↑ Husson & Valbelle (1992, pp. 11–15)

- ↑ Menu (1998, pp. 65–98)

- ↑ Menu (2004, pp. 47–54)

- ↑ Posener-Krieger, Paule (1976). Les Archives du temple funéraire de Néferirkarê-Kakai (Les Archives d'Abousir). IFAO.

- ↑ Grandet (1994)

- ↑ Menu (2004, pp. 54–56)

- ↑ Husson & Valbelle (1992, pp. 12–17)

- ↑ Bonhême & Forgeau (1988, pp. 321–322)

- ↑ Hoefer (1861)

- ↑ Vernus (2001, pp. 20–24)

- ↑ Vernus (2001, p. 135)

- ↑ Vernus (2001, p. 137)

- ↑ Sauneron, Serge (1998). Les prêtres de l'ancienne Égypte (in French). Paris: Le Seuil. ISBN 2906427020.

- ↑ Bonhême et al.

- ↑ Cauville (2011, pp. 3–17)

- ↑ Bonnamy & Sadek (2010, pp. 412–413)

- ↑ Betrò (1995, p. 241)

- ↑ Vernus (2001, p. 187)

- ↑ Posener (1960, pp. 29–35)

- ↑ Cauville (2011, pp. 11–17)

- ↑ Barguet (1986, pp. 471–472)

- ↑ Assmann (1999)

- ↑ Menu (2004, pp. 95–97)

- ↑ Moret (1902, pp. 138–140)

- ↑ Bonhême & Forgeau (1988, pp. 135–137)

- ↑ Cabrol (2000, pp. 325–326)

- ↑ Yoyote (1980, pp. 47–75)

- ↑ Goyon (2011)

- ↑ Bonhême & Forgeau (1988, p. 9–13)

- ↑ Posener (1960, pp. 60–61)

- ↑ Bonhême & Forgeau (1988, p. 127)

- ↑ Bonhême & Forgeau (1988, pp. 162–163)

- ↑ Bonhême & Forgeau (1988, pp. 150, 159, 160)

- ↑ Hoefer (1861, p. 84)

- ↑ Bonhême & Forgeau (1988, pp. 161–162)

- ↑ Vernus (2001, pp. 167–168)

- ↑ Bonhême & Forgeau (1988, pp. 164–166)

- ↑ Menu (1998, p. 123)

- ↑ Menu (2004, pp. 195–197)

- ↑ Menu (2004, pp. 198–201)

- ↑ Menu (2004, p. 31)

- ↑ Hornung, Erik (2007). Les Textes de l'au-delà dans l'Égypte ancienne (in French). Monaco: Le Rocher. p. 251.

- ↑ Assmann (1999, pp. 114–116)

- ↑ Vandier, Jacques (1961). Le Papyrus Jumilhac (in French). Paris: CNRS. p. 130.

- ↑ Clayton (1995, pp. 101–102)

- ↑ Clayton (1995, pp. 109–110)

- ↑ Clayton (1995, pp. 147–153)

- ↑ Clayton (1995, pp. 161–164)

- ↑ Bonhême & Forgeau (1988, p. 42)

- ↑ Obsomer, Claude (2012). Ramsès II. Pygmalion. p. 121.

- ↑ Menu (2004, p. 29)

- ↑ Luiselli (2011)

- ↑ Wilkinson (1999, p. 197)

- ↑ Menu (2004, p. 40)

- ↑ Maruéjol (2007, pp. 125–164, 444–445)

- ↑ Pietri, Renaud. Le roi en char au Nouvel Empire. pp. 13–22.

- ↑ Menu (1998, pp. 233–245)

- ↑ Bonhême & Forgeau (1988, pp. 179–180)

- ↑ Devauchelle, Didier. La Pierre de Rosette. Alternatives. p. 64. ISBN 9782862273808.

- ↑ Bonhême & Forgeau (1988, pp. 181–182)

- ↑ Chadefaud, Catherine (1993). L'écrit dans l'Égypte Ancienne (in French). Paris: Hachette Supérieur. p. 177.

- ↑ Maruéjol (2007, pp. 165–166, 173)

- ↑ Lalouette (1984, pp. 182–184, 328)

- ↑ Lalouette (1984, pp. 182–184)

- ↑ Menu (2004, p. 127)

- ↑ Hoefer (1861, pp. 94–95)

Bibliography

- Corteggiani, Jean-Pierre (2007). L'Égypte ancienne et ses dieux, dictionnaire illustré (in French). Paris: Éditions Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-62739-7.

- Betrò, Maria Carmela (1995). Hiéroglyphes : Les mystères de l'écriture (in French). Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-012465-X.

- Bonnamy, Yvonne; Sadek, Ashraf (2010). Dictionnaire des hiéroglyphes (in French). Arles: Actes Sud. ISBN 978-2-7427-8922-1.

- Assmann, Jan (1999). Maât, l'Égypte pharaonique et l'idée de justice sociale (in French). Fuveau: La Maison de Vie. ISBN 2909816346.

- Bonhême, Marie-Ange; Forgeau, Annie (1988). Pharaon : Les secrets du Pouvoir (in French). Paris: Armand Colin. ISBN 2200371209.

- Cabrol, Agnès (2000). Amenhotep III le magnifique. Monaco: Le Rocher. ISBN 2268035832.

- Clayton, Peter (1995). Chronique des Pharaons : L'histoire règne par règne des souverains et des dynasties de l'Égypte ancienne (in French). Translated by Maruéjol, Florence. Casterman. ISBN 2203233044.

- Cauville, Sylvie (2011). L'offrande aux dieux dans le temple égyptien (in French). Paris-Leuven (Belgique): Peeters. ISBN 9789042925687.

- Collectif (2014). Horemheb : Grand serviteur de l'État et pharaon (in French). Montségur: Égypte Afrique et Orient. ISSN 1276-9223.

- Husson, Geneviève; Valbelle, Dominique (1992). L'État et les institutions en Égypte des premiers pharaons aux empereurs romains (in French). Paris: Armand Colin. ISBN 2200313101.

- Lalouette, Claire (1984). Textes sacrés et textes profanes de l'ancienne Égypte I - Des Pharaons et des hommes (in French). Preface by Pierre Grimal. Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 2070711765.

- Luiselli, Maria Michela (2011). The Ancient Egyptian scene of Pharaoh smiting his enemies: an attempt to visualize cultural memory?. London: Cultural Memory and Identity in ancient Societies.

- Maruéjol, Maruéjol (2007). Thoutmosis III et la corégence avec Hatchepsout (in French). Paris: Pygmalion. ISBN 9782857048947.

- Menu, Bernadette (1998). Recherches sur l'histoire juridique, économique et sociale de l'ancienne Égypte. II (in French) (122 ed.). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 9782724702170.

- Menu, Bernadette (2004). Égypte pharaonique : Nouvelles recherches sur l'histoire juridique, économique et sociale de l'ancienne Égypte (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2747577066.

- Posener, Georges (1960). De la divinité du pharaon (in French) (15 ed.). Paris: Cahiers de la Société Asiatique.

- Yoyote, Jean (1980). Une monumentale litanie de granit. Les Sekhmet d'Aménophis III et la conjuration permanente de la Déesse dangereuse (in French) (87-88 ed.). Paris: BSFE.

- Wilkinson, Toby A.H. (1999). Early Dynastic Egypt. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415186331.

- Barguet, Paul (1986). Textes des Sarcophages égyptiens du Moyen Empire (in French). Paris: Éditions du Cerf. ISBN 2204023329.

- Hoefer, Ferdinand (1861). Bibliothèque historique de Diodore de Sicile (in French) (1 ed.). Paris: Librairie L. Hachette.

- Goyon, Jean-Claude (2011). Le Rituel du shtp Shmt au changement de cycle annuel (in French). Cairo: IFAO.

- Grandet, Pierre (1994). Le papyrus Harris I (BM 9999) (in French). Vol. 141 (2nd ed.). Cairo: l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire. ISBN 2724704150.

- Moret, Alexandre (1902). Le rituel du culte divin journalier en Égypte : D'après les papyrus de Berlin et les textes tu temple de Séti Ier, à Abydos (in French). Geneva: Slatkine Reprints.

- Vernus, Pascal (2001). Sagesses de l'Égypte pharaonique (in French). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale. ISBN 2743303328.