Geographical exploration, sometimes considered the default meaning for the more general term exploration, refers to the practice of discovering remote lands and regions of the planet Earth.[1] It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most of Homo sapiens history, saw humans moving out of Africa, settling in new lands, and developing distinct cultures in relative isolation.[2] Early explorers settled in Europe and Asia; 14,000 years ago, some crossed the Ice Age land bridge from Siberia to Alaska, and moved southbound to settle in the Americas.[1] For the most part, these cultures were ignorant of each other's existence.[2] The second period of exploration, occurring over the last 10,000 years, saw increased cross-cultural exchange through trade and exploration, and marked a new era of cultural intermingling, and more recently, convergence.[2]

Early writings about exploration date back to the 4th millennium B.C. in ancient Egypt. One of the earliest and most impactful thinkers of exploration was Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD. Between the 5th century and 15th century AD, most exploration was done by Chinese and Arab explorers. This was followed by the Age of Discovery after European scholars rediscovered the works of early Latin and Greek geographers. While the Age of Discovery was partly driven by European land routes becoming unsafe,[3] and a desire for conquest, the 17th century saw exploration driven by nobler motives, including scientific discovery and the expansion of knowledge about the world.[1] This broader knowledge of the world's geography meant that people were able to make world maps, depicting all land known. The first modern atlas was the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, published by Abraham Ortelius, which included a world map that depicted all of Earth's continents.[4]: 32

Concept

Exploration is the process of exploring, which has been defined as:[5]

- To examine or investigate something systematically.

- To travel somewhere in search of discovery.

- To examine diagnostically.

- To (seek) experience first hand.

- To wander without any particular aim or purpose.

Notable historical periods of human exploration

Phoenician galley sailings

The Phoenicians (1550 BCE–300 BCE) traded throughout the Mediterranean Sea and Asia Minor though many of their routes are still unknown today. The presence of tin in some Phoenician artifacts suggests that they may have traveled to Britain. According to Virgil's Aeneid and other ancient sources, the legendary Queen Dido was a Phoenician from Tyre who sailed to North Africa and founded the city of Carthage.

Carthaginean exploration of Western Africa

Hanno the Navigator (500 BC), a Carthaginean navigator who explored the Western Coast of Africa.

Greek and Roman exploration of Northern Europe and Thule

- Pytheas (4th century BC), a Greek explorer from Massalia (Marseille), was the first to circumnavigate Great Britain, explore Germany, and reach Thule (most commonly thought to be the Shetland Islands or Iceland).

- Under Augustus, Romans reached and explored all the Baltic Sea.

Roman explorations

- Africa exploration

The Romans organized expeditions to cross the Sahara desert along five different routes:

- through the western Sahara, toward the Niger River and Timbuktu.

- through the Tibesti Mountains, toward Lake Chad and Nigeria.

- through the Nile river, toward Uganda.

- through the western coast of Africa, toward the Canary Islands and the Cape Verde islands.

- through the Red Sea, toward Somalia and perhaps Tanzania.

All these expeditions were supported by legionaries and had mainly a commercial purpose. Only the one done by emperor Nero seemed to be a preparation for the conquest of Ethiopia or Nubia: in 62 AD two legionaries explored the sources of the Nile.

One of the main reasons of the explorations was to get gold using the camel to transport it.[6]

The explorations near the African western and eastern coasts were supported by Roman ships and deeply related to the naval commerce (mainly toward the Indian Ocean). The Romans also organized several explorations into Northern Europe, and explored as far as China in Asia.

- 30 BC – 640 AD

- With the acquisition of Ptolemaic Egypt, the Romans begin trading with India. The Romans now have a direct connection to the spice trade, which the Egyptians had established beginning in 118 BC.

- 100–166 AD

- Sino-Roman relations begin. Ptolemy writes of the Golden Chersonese (i.e. Malay Peninsula) and the trade port of Kattigara, now identified as Óc Eo in northern Vietnam, then part of Jiaozhou, a province of the Chinese Han Empire. The Chinese historical texts describe Roman embassies, from a land they called Daqin.

- 161

- An embassy from Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius or his successor Marcus Aurelius reaches Chinese Emperor Huan of Han at Luoyang.

- 226

- A Roman diplomat or merchant lands in northern Vietnam and visits Nanjing, China and the court of Sun Quan, ruler of Eastern Wu.

Chinese exploration of Central Asia

During the 2nd century BC, the Han dynasty explored much of the Eastern Northern Hemisphere. Starting in 139 BC, the Han diplomat Zhang Qian traveled west in an unsuccessful attempt to secure an alliance with the Da Yuezhi against the Xiongnu (the Yuezhi had been evicted from Gansu by the Xiongnu in 177 BC); however, Zhang's travels discovered entire countries which the Chinese were unaware of, including the remnants of the conquests of Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 BC).[7] When Zhang returned to China in 125 BC, he reported on his visits to Dayuan (Fergana), Kangju (Sogdia), and Daxia (Bactria, formerly the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom which had just been subjugated by the Da Yuezhi).[8] Zhang described Dayuan and Daxia as agricultural and urban countries like China, and although he did not venture there, described Shendu (the Indus River valley of Northwestern India) and Anxi (Parthian territories) further west.[9]

Viking Age

From about 800 AD to 1040 AD, the Vikings explored Iceland and much of the Western Northern Hemisphere via rivers and oceans. For example, it is known that the Norwegian Viking explorer, Erik the Red (950–1003), sailed to and settled in Greenland after being expelled from Iceland, while his son, the Icelandic explorer Leif Erikson (980–1020), reached Newfoundland and the nearby North American coast, and is believed to be the first European to land in North America.

Polynesian Age

Polynesians were a maritime people, who populated and explored the central and south Pacific for around 5,000 years, up to about 1280 when they discovered New Zealand. The key invention to their exploration was the outrigger canoe, which provided a swift and stable platform for carrying goods and people. Based on limited evidence, it is thought that the voyage to New Zealand was deliberate. It is unknown if one or more boats went to New Zealand, or the type of boat, or the names of those who migrated. 2011 studies at Wairau Bar in New Zealand show a high probability that one origin was Ruahine Island in the Society Islands. Polynesians may have used the prevailing north easterly trade winds to reach New Zealand in about three weeks. The Cook Islands are in direct line along the migration path and may have been an intermediate stopping point. There are cultural and language similarities between Cook Islanders and New Zealand Māori. Early Māori had different legends of their origins, but the stories were misunderstood and reinterpreted in confused written accounts by early European historians in New Zealand trying to present a coherent pattern of Māori settlement in New Zealand.

Mathematical modelling based on DNA genome studies, using state of the art techniques, have shown that a large number of Polynesian migrants (100–200), including women, arrived in New Zealand around the same time, in about 1280. Otago University studies have tried to link distinctive DNA teeth patterns, which show special dietary influence, with places in or nearby the Society Islands.[10]

Chinese exploration of the Indian Ocean

The Chinese explorer, Wang Dayuan (fl. 1311–1350) made two major trips by ship to the Indian Ocean. During 1328–1333, he sailed along the South China Sea and visited many places in Southeast Asia and reached as far as South Asia, landing in Sri Lanka and India, and he even went to Australia. Then in 1334–1339, he visited North Africa and East Africa. Later, the Chinese admiral Zheng He (1371–1433) made seven voyages to Arabia, East Africa, India, Indonesia, and Thailand.

European Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery, also known as the Age of Exploration, is one of the most important periods of geographical exploration in human history. It started in the early 15th century and lasted until the 17th century. In that period, Europeans discovered and/or explored vast areas of the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Oceania. Portugal and Spain dominated the first stages of exploration, while other European nations followed, such as England, France, and the Netherlands.

Important explorations during this period went to a number of continents and regions around the globe. In Africa, important explorers of this period include Diogo Cão (1452–1486), who discovered and ascended the Congo River and reached the coasts of present-day Angola and Namibia; and Bartolomeu Dias (1450–1500), the first European to reach the Cape of Good Hope and other parts of the South African coast.

Explorers of routes from Europe towards Asia, the Indian Ocean, and the Pacific Ocean, include Vasco da Gama (1460–1524), a navigator who made the first trip from Europe to India and back by the Cape of Good Hope, discovering the ocean route to the East; Pedro Álvares Cabral (1467/1468–1520), who, following the path of Vasco da Gama, claimed Brazil and led the first expedition that linked Europe, Africa, America, and Asia; Diogo Dias, who discovered the eastern coast of Madagascar and rounded the corner of Africa; explorers such as Diogo Fernandes Pereira and Pedro Mascarenhas (1470–1555), among others, who discovered and mapped the Mascarene Islands and other archipelagos.

António de Abreu (1480–1514) and Francisco Serrão (14??–1521) led the first direct European fleet into the Pacific Ocean (on its western edges) and through the Sunda Islands, reaching the Moluccas. Andrés de Urdaneta (1498–1568) discovered the maritime route from Asia to the Americas.

In the Pacific Ocean, Jorge de Menezes (1498–1537) reached New Guinea while García Jofre de Loaísa (1490–1526) reached the Marshall Islands.

- Discovery of America

Explorations of the Americas began with the initial discovery of America by Christopher Columbus (1451–1506), who led a Castilian (Spanish) expedition across the Atlantic, discovering America. After the discovery of America by Columbus, a number of important expeditions were sent out to explore the Western Hemisphere. This included Juan Ponce de León (1474–1521), who discovered and mapped the coast of Florida; Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475–1519), who was the first European to view the Pacific Ocean from American shores (after crossing the Isthmus of Panama) confirming that America was a separate continent from Asia; Aleixo Garcia (14??–1527), who explored the territories of present-day southern Brazil, Paraguay and Bolivia, crossing the Chaco and reaching the Andes (near Sucre).

Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (1490–1558) discovered the Mississippi River and was the first European to sail the Gulf of Mexico and cross Texas. Jacques Cartier (1491–1557) drew the first maps of part of central and maritime Canada; Francisco Vázquez de Coronado (1510–1554) discovered the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River; Francisco de Orellana (1511–1546) was the first European to navigate the length of the Amazon River.

- Further explorations

Ferdinand Magellan (1480–1521), was the first navigator to cross the Pacific Ocean, discovering the Strait of Magellan, the Tuamotus and Mariana Islands, and achieving a nearly complete circumnavigation of the Earth, in multiple voyages, for the first time. Juan Sebastián Elcano (1476–1526), completed the first global circumnavigation.

In the second half of the 16th century and the 17th century exploration of Asia and the Pacific Ocean continued with explorers such as Andrés de Urdaneta (1498–1568), who discovered the maritime route from Asia to the Americas; Pedro Fernandes de Queirós (1565–1614), who discovered the Pitcairn Islands and the Vanuatu archipelago; Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira (1542–1595), who discovered the Tuvalu archipelago, the Marquesas, the Solomons, and Wake Island.

Explorers of Australia included Willem Janszoon (1570–1630), who made the first recorded European landing in Australia; Yñigo Ortiz de Retez, who discovered and reached eastern and northern New Guinea; Luis Váez de Torres (1565–1613), who discovered the Torres Strait between Australia and New Guinea; Abel Tasman (1603–1659), who explored North Australia, discovered Tasmania, New Zealand, and Tongatapu.

In North America, major explorers included Henry Hudson (1565–1611), who explored the Hudson Bay in Canada; Samuel de Champlain (1574–1635), who explored St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes (in Canada and northern United States); and René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (1643–1687), who explored the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada, and the entire length of the Mississippi River.

Late modern period

Long after the Age of Discovery, other explorers "completed" the world map, such as various Russian explorers, reaching the Siberian Pacific coast and the Bering Strait, at the extreme edge of Asia and Alaska (North America); Vitus Bering (1681–1741) who in the service of the Russian Navy, explored the Bering Strait, the Bering Sea, the North American coast of Alaska, and some other northern areas of the Pacific Ocean; and James Cook, who explored the east coast of Australia, the Hawaiian Islands, and circumnavigated Antarctica.

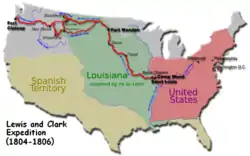

There were still significant explorations which occurred well into the late modern period. This includes the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806), an overland expedition dispatched by President Thomas Jefferson to explore the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase and to find an interior aquatic route to the Pacific Ocean, along with other objectives to examine the flora and fauna of the continent. In 1818, the British researcher John Ross was the first to find that the deep sea is inhabited by life when catching jellyfish and worms in about 2,000 m (6,562 ft) depth with a special device. The United States Exploring Expedition (1838–1842) was an expedition sent by President Andrew Jackson, in order to survey the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands.

The extreme conditions in the deep sea require elaborate methods and technologies to endure them. In the 20th century, deep-sea exploration advanced considerably through a series of technological inventions, ranging from the sonar system, which can detect the presence of solid objects underwater through the use of reflected sound, to manned deep-diving submersibles. In 1960, Jacques Piccard and United States Navy Lieutenant Donald Walsh descended in the bathyscaphe Trieste into the deepest part of the world's oceans, the Mariana Trench.[11] In 2018, DSV Limiting Factor, piloted by Victor Vescovo, completed the first mission to the deepest point of the Atlantic Ocean, diving 8,375 m (27,477 ft) below the ocean surface to the base of the Puerto Rico Trench.[12] With the advent of satellite imagery and aviation, broad scale exploration of the surface of Earth has largely ceased, however the culture of many disconnected tribes still remain undocumented and left to be explored, and the details of more inaccessible ecosystems remains undescribed. Urban exploration is the exploration of manmade structures, usually abandoned ruins or hidden components of the manmade environment.

Space age

Space exploration started in the 20th century with the invention of exo-atmospheric rockets. This has given humans the opportunity to travel to the Moon, and to send robotic explorers to other planets and far beyond.

Both of the Voyager probes have left the Solar System, bearing imprinted gold discs with multiple data types.

Underwater exploration

Objectives

The scope of underwater exploration includes the distribution and variety of marine and aquatic life, measurement of the geographical distribution of the chemical and physical properties, including movement of the water, and the geophysical, geological and topographical features of the Earth's crust where it is covered by water.[13]

Systematic, targeted exploration is the most effective method to increase understanding of the ocean and other underwater regions, so they can be effectively managed, conserved, regulated, and their resources discovered, accessed, and used. The ocean covers approximately 70% of Earth’s surface and has a critical role in supporting life on the planet but knowledge and understanding of the ocean remains limited due to difficulty and cost of access.[14]

The distinction between exploration, survey, and other research is somewhat blurred, and one way of looking at it is to consider the baseline surveys and research as exploration, as previously unknown information is gathered. Updating and refining the data is less exploratory in nature, but may still be exploration for the people involved, in the sense that the experience is new to them.

Status

According to NOAA, as of January 2023: "More than eighty percent of our ocean is unmapped, unobserved, and unexplored." Less than 10% of the ocean, including about 35% of the ocean and coastal waters of the United States, have been mapped in any detail using sonar technology. [15] According to GEBCO 2019 data, less than 18% of the deep ocean bed has been mapped using direct measurement and about 50% of coastal waters were not yet surveyed.[16]

Most of the data used to create global seabed maps are approximate depths derived from satellite gravity measurements and sea surface heights which are affected by the shape and mass distribution of the seabed. This method of approximation only provides low resolution information on large topographical features, and can miss significant features.[17]

See also

- Early human migrations – Spread of humans from Africa through the world

- Timeline of European exploration

- Timeline of maritime migration and exploration

- European exploration of Africa – Period of history

- List of explorations

- List of explorers

- List of maritime explorers

- List of underwater explorers

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 Royal Geographical Society (2008). Atlas of Exploration. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534318-2. Archived from the original on October 16, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2022 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (October 17, 2007). Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-24247-8. Archived from the original on October 16, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "European exploration - The Age of Discovery | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ↑ "Chapter 2 - Brief History of Land Use—" (PDF). Global Land Outlook (Report). United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. 2017. ISBN 978-92-95110-48-9. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ↑ Wiktionary contributors (30 November 2022). "explore". Wiktionary, The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ↑ Roth, Jonathan 2002. The Roman Army in Tripolitana and Gold Trade with Sub-Saharan Africa. APA Annual Convention. New Orleans.

- ↑ di Cosmo 2002, pp. 247–249; Yü 1986, p. 407; Torday 1997, p. 104; Morton & Lewis 2005, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Torday 1997, pp. 105–106.

- ↑ Torday 1997, pp. 108–112.

- ↑ Otago University. Wairau Bar Studies 2011. Dr L. Matisoo-Smith.

- ↑ "Jacques Piccard: Oceanographer and pioneer of deep-sea exploration – Obituaries, News". The Independent. London. 2008-11-05. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ↑ Neate, Rupert (2018-12-22). "Wall Street trader reaches bottom of Atlantic in bid to conquer five oceans". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- ↑ Baker, D. James; Rechnitzer, Andreas B. "Undersea exploration". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ↑ "Why do we explore the ocean?". oceanexplorer.noaa.gov. NOAA. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ↑ "How much of the ocean have we explored?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ↑ "IHO Data Centre for Digital Bathymetry (DCDB)". www.ngdc.noaa.gov. NOAA. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ↑ "Seabed 2030: Map the Gaps". www.ncei.noaa.gov. 29 June 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

Sources

- di Cosmo, Nicola (2002). Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77064-4.

- Groh, Arnold (2018). Research Methods in Indigenous Contexts. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-72774-5.

- Morton, William Scott; Lewis, Charlton M. (2005). China: Its History and Culture (Fourth ed.). New York City: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-141279-7.

- Petringa, Maria (2006). Brazzà, a Life for Africa. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. ISBN 1-4259-1198-6. OCLC 74651678.

- Torday, Laszlo (1997). Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. Durham: The Durham Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-900838-03-0.

- Yü, Ying-shih (1986). "Han Foreign Relations". In Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge History of China. Vol. I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C.–A.D. 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 377–462. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

Further reading

- Chaudhuri, K. N. (1991). The Times Atlas of World Exploration: 3,000 Years of Exploring, Explorers, and Mapmaking. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-270032-2.

- Buiisseret, David, ed. (2007). The Oxford Companion to World Exploration. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514922-7.

External links

- National Geographic Explorer Program

- NOAA Ocean Explorer – provides public access to current information on a series of NOAA scientific and educational explorations and activities in the marine environment

- NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research – formed by the merger of NOAA's Undersea Research Program (NURP) and the Office of Ocean Exploration (OE)