| History of Virginia |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Slavery in Virginia began with the capture and enslavement of Native Americans during the early days of the English Colony of Virginia and through the late eighteenth century. They primarily worked in tobacco fields. Africans were first brought to colonial Virginia in 1619, when 20 Africans from present-day Angola arrived in Virginia aboard the ship The White Lion.

As the slave trade grew, enslaved people generally were forced to labor at large plantations, where their free labor made plantation owners rich. Colonial Virginia became an amalgamation of Algonquin-speaking Native Americans, English, other Europeans, and West Africans, each bringing their own language, customs, and rituals. By the eighteenth century, plantation owners were the aristocracy of Virginia. There were also a class of white people who oversaw the work of enslaved people, and a poorer class of whites that competed for work with freed blacks.

Tobacco was the key export of the colony in the seventeenth century. Slave breeding and trading gradually became more lucrative than exporting tobacco during the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century. Black human beings were the most lucrative and profitable export from Virginia, and black women were bred to increase the number of enslaved people for the slave trade.

In 1661, the Virginia General Assembly passed its first law allowing any free person the right to own slaves. The suppression and apprehension of runaway slave labor was the object of 1672 legislation.[1] Additional laws regarding slavery of Africans were passed in the seventeenth century and codified into Virginia's first slave code in 1705. Over time, laws denied increasingly more of the rights of and opportunities for enslaved people, and supported the interests of slaveholders.

For more than 200 years, enslaved people had to deal with a wide range of horrors, such as physical abuse, rape, being separated from family members, lack of food, and degradation. Laws restricted their ability to learn to read and write, so that they could not have books or Bibles. They had to ask permission to leave the plantation, and could leave for only a specified number of hours. During the early period of their American captivity, if they wanted to attend church, they were segregated from white congregants in white churches, or they had to meet secretly in the woods because blacks were not allowed to meet in groups, until later when they were able to establish black churches. The worst difficulty was being separated from family members when they were sold; consequently, they developed coping mechanisms, such as passive resistance, and creating work songs to endure the harsh days in the fields. Thus they created their own musical styles, including Black Gospel music and sorrow songs.

In 2007, the Virginia General Assembly approved a formal statement of "profound regret" for the Commonwealth's history of slavery.

Overview

When English settlers arrived in the seventeenth century in what became the colony of Virginia, there were 30 or so tribes of Native Americans, in a loose confederacy led by Powhatan. He lived in the region of the James River[2] and was the father of Pocahontas, who later married a colonist.[3] Numerous colonists starved during the colony's early years.[4] Kathryn Knight, author of Unveiled - The Twenty & Odd, about a group of captives from the Kingdom of Ndongo who were the first Africans in Virginia, says of the immigrants: "Basically all of those people were right off of the streets in England... [they] didn't know how to grow anything. They didn't know how to manage livestock. They didn't know anything about survival in Virginia... [Africans and Native Americans] saved them by being able to produce crops, by being able to manage the livestock. They kept them alive."[5] The English settlers and traders began enslaving Native Americans soon after founding Jamestown.[6]

Africans were brought by Dutch and English slave ships to the Virginia Colony. The plantation system developed over the seventeenth century and was increasingly inequitable, with the institution of slavery evolving gradually, at first by custom and then through the imposition of laws, from regulating indentured servitude to eventually making life-long servitude legal.[7] Laws and practices limited the behavior of African Americans, for example, by not allowing blacks to meet in groups, have firearms, or raise livestock. They could only leave plantations for four hours, and needed written permission to travel. Over time, being a Christian did not prevent African Americans from suffering life-long servitude.[7] Laws vacillated over time concerning the enslavement of Native Americans.[6] Algonquin-speaking Native Americans, English, other Europeans, and West Africans brought customs and traditions from each of their home countries and "loosely-knit customs began to crystallize into what later became known as the Tuckahoe culture".[8]

During the colonial period, settlements were established in the James River valley at major river crossings. There were few stores, and churches, and no public schools, and churches.[9] The valley was known for its large tobacco plantations of thousands of acres in the Tidewater coastal plain and on the Piedmont plateau.[8][9] On these plantations, tobacco planters treated field, household and skilled workers like chattel (owned property). Growing the labor-intensive tobacco crops, and later the cotton crops, of the South required large tracts of land and relied on slavery to be profitable. Social and political inequality between the planters and the other classes became more pronounced as planters became wealthier.[10] In 1860, there were 20,000 enslaved people that lived in Arlington, Fairfax, Loudoun, and Prince William counties.[11]

Plantation owners in Virginia became wealthy during the eighteenth century, as well as members of a new planter aristocracy, by growing tobacco and employing unpaid enslaved people to perform this and other agricultural and domestic labor.[12][13] The planters were far outnumbered by indentured servants, slaves, and poor white people.[10] Thomas Anburey, an English officer, visited Colonel Randolph's house in Goochland in 1779 and opined that Virginia plantations were owned and operated by refined, educated people. He thought the class of whites who had the most interaction with their slaves were uneducated and unworldly, and generally "hospitable, generous, and friendly", but qualified his estimation with the statement that they were "accustomed to tyrannize with all their good qualities, they are rude, ferocious, and haughty, much attached to gaming and dissipation".[9]

Plantations were few in number in colonial Virginia, but were key to the economic welfare of the colony. History often obscures the realities of slavery during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by focusing on the history of the plantation owners and the architecture of the plantation manors, relegating enslaved people to the margins of the history of the plantations.[14] As historical plantation sites such as Thomas Jefferson's Monticello, George Washington's Mount Vernon, and other plantations throughout the South attempt to provide a fuller picture of colonial life and slavery, some visitors prefer not to hear it.[15]

Slavery continued until the passage of the 13th Amendment that abolished slavery in 1865. There were laws enacted and other practices that limited African Americans rights and opportunities after the Emancipation Proclamation.[12]

Slavery

Native Americans

After the first Africans arrived at Jamestown in 1619, slavery and other forms of bondage were found in all the English colonies; some Native Americans were enslaved by the English, with a few slaveholders having both African and Native American slaves,[16] who worked in their tobacco fields. Laws regarding enslavement of Native Americans vacillated between encouraging and discouraging slavery. The number of enslaved native people reached a peak at the end of the seventeenth century.

The colony of Virginia formally ended Indian slavery in 1705. The practice had already declined because Native Americans could escape into familiar territory, and also suffered from new infectious diseases introduced by the colonists, among whom these were endemic. The Atlantic slave trade began to provide numerous African captives to replace them as laborers. The enslavement of indigenous people continued into the end of the eighteenth century; by the nineteenth century, they were either incorporated within African-American communities or were free.[6]

Europeans sold guns for slaves in an existing indigenous trading market, and encouraged allied tribes to provide the slaves by targeting Indian groups on the periphery of English settlements.

Indigenous people were generally taken in the greatest numbers during battles between the English and Native Americans.[6] They attacked or fought one another for years, partly because of the English people's lack of food and the Native Americans' distress that they were losing their land. On March 22, 1622, 347 or more colonists were killed and English settlements were set on fire during an Indian massacre. Approximately 20 women were taken from Martin's Hundred plantation on the James River and were said to have been put into "great slavery".[17] To prevent escape, the English sent captured Native Americans to British colonies in the West Indies to work as slaves.[18][19][lower-alpha 1]

First Africans

In late August 1619, twenty or more Africans were brought to Point Comfort on the James River in Virginia. They were sold first in exchange for food and then sold in Jamestown as indentured servants.[21][lower-alpha 2] The Africans came from the Kingdom of Ndongo, in what is now Angola.[5] Angela, an enslaved woman from Ndonggo, was one of the first enslaved Africans to be officially recorded in the colony of Virginia in 1619.[24]

By 1620, there were 32 Africans and four Native Americans in the "Others not Christians in the Service of the English" category of the muster who arrived in Virginia, but that number was reduced by 1624, perhaps due to the Second Anglo-Powhatan War (1622–1632) or illness.[21][25] William Tucker, born in 1624, was the first person of African descent born in the Thirteen Colonies.[26]

There were 906 Europeans and 21 Africans in the 1624 muster. By 1625, the Africans lived on plantations;[21] many of them were baptized as Christians and took Christian names. In 1628, a slave ship carried 100 people from Angola to be sold into slavery in Virginia, and consequently the number of Africans in the colony rose greatly.[21][25][27]

The Atlantic slave trade had been in existence among Europeans before Africans landed in Virginia and according to custom, slavery was legal. Unlike white indentured servants, blacks could not negotiate a labor contract, nor could African Americans effectively defend their rights without paperwork. By the mid-1600s, seven legal suits had been filed by African Americans asserting their claim to a limited period of service. In six of the cases, their enslavers claimed that they were bound for life.[28] Since 1990, after over 30 years of scholarly debate, the dominant consensus is that "the vast majority" of Africans were treated like slaves by their slaveholders. It was very rare for blacks to have a legal indenture, but there were some people who attained freedom in a number of different ways.[29]

Mary and Anthony Johnson were among the few African Americans who were able to gain their freedom, herd livestock, and establish a prosperous farm.[30] In 1640, one black servant, John Punch, ran away and was sentenced by the Virginia courts to slavery for the rest of his life. Two white indentured servants who ran away with Punch had four more years added on to their servitude.[31]

Unpaid servants

Household and farm work was performed by indentured servants and enslaved people, including children.[12][lower-alpha 3] Indentured servants, generally brought from England, worked without pay for a specific length of time.[33] They exchanged their labor for the cost of their passage to the colony, room and board, and freedom dues, which were stipulated to be provided to the servant at the end of the indenture period, and could include land and supplies that would help them become established on their own.[27][34] In the seventeenth century, the tobacco fields of Virginia were mostly worked by white indentured servants. By 1705, the economy was based upon slave labor imported from Africa.[35]

Enslaved people were generally held for their lifetimes. Children of enslaved women were enslaved from birth per the legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem.[33] Some commentators hold that since the muster and other records used the term "servant" that it meant that blacks who landed in Virginia were indentured servants. Unlike indentured servants, slaves were taken against their will. When slaves were first sold in exchange for food, it was clear that they were considered property. The term "indentured servitude" was often a euphemism for slavery when referring to white people.[36] Enslaved blacks were treated much more harshly than white servants. Whipping of blacks, for instance, was common.[33][lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5]

Domestic, field, and skilled labor

From Monday through Saturday, enslaved people were assigned specific duties. Most people, including children, were farm hands.[38] Domestic work, another duty, included preparing and serving food, cleaning, and caretaking of white children; others were trained to be blacksmiths, carpenters, and coopers.[38] Those who had livestock or gardens tended to them on Sunday. It was also a day to be with family and for worship.[38]

Children also worked; for instance, by the late eighteenth century at Monticello, small black children helped with tasks at the main house and looked after enslaved toddlers until they were ten years of age. At that time, they were assigned to work in the fields, the house, or to learn a specific skill such as the making of nails or textiles. At the age of 16, they might be forced into a trade.[39] Domestic work was not as onerous as field work and provided opportunities to overhear gossip and news. Life was more difficult for children who worked in the fields, particularly on large plantations, but it was most difficult when family members were sold away from the farm or plantation. Some planters cruelly mistreated those in their charge.[40]

Offenses against slaves

.JPG.webp)

Enslavers had control of the people that they enslaved. They could favor some, make life miserable for others, tease them with hollow promises of emancipation, brutally rape, and severely punish slaves. They could also control what happened to their children, which was a very powerful tactic. Slaves could not testify against their masters in a court case, making their situation more difficult.[41] In 1829, the North Carolina v. Mann case was brought before the North Carolina Supreme Court, which ruled that slaveholders had the right to treat enslaved people in any way that they chose, including killing them, in order to better the "submission" of the enslaved to their masters.[42]

Into the first half of the nineteenth century, it was common practice at southern universities, such as the University of Virginia (UVA), for white men to rape the enslaved women and children who served them. Over the years, between 100 and 200 black men, women and children who worked at the university were mistreated and beaten.[43][lower-alpha 6] The behavior was accepted by law enforcement and schools.[43] In September 1826, two students at the university, George Hoffman and Turner Dixon, caught the same sexually transmitted disease, which they deduced was caught from the same girl, who had been raped by both men. They and other classmates found the 16-year-old victim and beat her until she was bloody. After her owner complained to the college, the young men were reprimanded and ordered to pay $10 to the slaveholder.[43][lower-alpha 7]

After 1808, when Congress made the Atlantic slave trade illegal, prohibiting importation of slaves from the West Indies or Africa, the domestic slave trade increased. The slave trade grew in the country through breeding enslaved women so that their children could be sold for profit.[44]

Progeny

From the 1600s until 1860, it was common for white planters, overseers, or other white men to rape enslaved women. Because of the disparity of power between enslaved women and the men who fathered their children, and the fact that the men had unlimited access to such forced sex, "all of the sex that took place between enslaved women and white men constituted some form of sexual assault."[42]

Since children followed their mother's status, the children of enslaved women increased a slaveholder's work force. It met the economic needs of the colony, which suffered perpetual labor shortages because conditions were difficult, mortality was high, and the government had difficulty attracting sufficient numbers of English indentured servants after economic conditions improved in England.[45] This resulted in generations of black and mixed-race enslaved people. Among the most notable were Sally Hemings and her siblings, fathered by planter John Wayles, and her four surviving children by Thomas Jefferson.[46] This was in contrast to English common law of the time.[lower-alpha 8]

Formalized slavery

It was in Virginia that a legal process emerged guaranteeing that the 'cruelty of slavery and pervasive racial injustice were guaranteed by its laws.'

—Leon A. Higginbotham quoted in "The 'Twenty and Odd': The Silences of Africans in Early Virginia Revealed" [47]

A law making race-based slavery legal was passed in Virginia in 1661.[21] It allowed any free person the right to own slaves.[48] In 1662, the Virginia House of Burgesses passed a law that said a child was born a slave if the mother was a slave, based on partus sequitur ventrem. Specifically, "all children borne in this country shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother." The new law in 1662 was an effort to define the status of non-English subjects in Virginia. It was passed in part because of a freedom suit in which Elizabeth Key, a mixed-race daughter of an Englishman, who had been baptized as Christian, won her freedom by a colonial decision. The law also resulted in freeing white fathers from any responsibilities toward their mixed-race children. If they owned them, they could put them to work or sell them.[45] It also voided the previous prohibition against enslaving Christians. The colonial law was in contrast to English common law of the time that prevailed in England. [lower-alpha 9] Slavery created a racial caste associated with African descent regardless of a child's paternal ancestry. The principle became incorporated into state law when Virginia gained independence from Great Britain.[49]

Additional laws regarding slavery were passed in the seventeenth century and in 1705 were codified into Virginia's first slave code,[48] An act concerning Servants and Slaves. The Virginia Slave Codes of 1705 stated that people who were not Christians, or were black, mixed-race, or Native Americans would be classified as slaves (i.e., treated like personal property or chattel), and it was made illegal for white people to marry people of color.[50] Slaveholders were given permission to punish enslaved people and would not be prosecuted if the slave died as a result. The law specified punishment, including whipping and death, for minor offenses and for criminal acts. Slaves needed written permission, known as passes, to leave their plantation.

Servants, differentiated from slaves, had rights to safety, the receipt of food and goods at the end of their term of service, and to resolve legal issues first with a justice of the peace, then in court, if needed.[50] Virginia had a longer list of offenses that a black person could commit than any other southern colony. Blacks did not benefit from legal procedures that would allow them to properly plead their case and prove their innocence, nor did they have the right to appeal decisions.[51]

Plantations and farms

Virginia planters developed the commodity crop of tobacco as their chief export. It was a labor-intensive crop, and demand for it in England and Europe led to an increase in the importation of African slaves in the colony.[52] European servants were replaced by enslaved blacks during the seventeenth century, as they were a more profitable source of labor. Slavery was supported through legal and cultural changes. Virginia is where the first enslaved blacks were imported to English colonies in North America, and slavery spread from there to the other colonies.[53] Large plantations became more prevalent, changing the culture of colonial Virginia that relied on them for its economic prosperity. The plantation "served as an institution in itself, characterized by social and political inequality, racial conflict, and domination by the planter class."[10]

Tobacco farming in eastern Virginia so depleted the fertility of its soil that by 1800, farmers began to look to the west for good land to raise crops. John Randolph said in 1830 that the land was "worn out." Corn and wheat were grown in the Piedmont plateau and the Shenandoah Valley. The number of slaves in the Shenandoah Valley were never as high as in eastern Virginia. The area was settled by German and Scotch-Irish people, who had little need for or interest in slavery, and the absence of competition with unpaid slave labor prevented the development of class divisions like those in the east.[54][55] In western Virginia, the economy was based upon raising livestock and farming. It was not economical to use slave labor except for the few tobacco farms, coal mines, or the salt industry. The coal and salt industry leased enslaved people who were hired out,[56] mostly from eastern Virginia, because their risk of death was high enough that purchasing enslaved people was not cost effective. Poor white people also worked in these industries. The slaves that were no longer needed or marketable within Virginia were hired out or sold to work in the cotton fields of the Deep South.[55][57] The slave population increased in the counties now encompassing West Virginia in the years 1790 to 1850, but saw a decrease from 1850 to 1860,[58] by which year four percent (18,451) of western Virginia's total population were slaves, while slaves in eastern Virginia were about thirty percent (490,308) of the total population.[59][lower-alpha 10][lower-alpha 11] With a shortage of white labor, blacks had become deeply involved in urban trades and businesses. In this setting, slaves were able to buy their way out of slavery.[61]

Eastern Virginia's interests were very different from those of the northwestern border counties. The state of West Virginia was formed from the northwestern counties of Virginia as well as counties from the southwest and the Valley. Federal statehood was granted in 1863.[62] West Virginia was a divided state during the Civil War, half of the counties had voted for the Confederacy in 1861 and half its soldiers were Confederate.[63] It entered the Union as a slave state.

Culture

African Americans developed cultural traditions that helped them cope with being enslaved, supported family members and friends, and promoted their human dignity. Music, folklore, cuisine, and religious practices by blacks influenced the broader American culture.[38] Africans contributed to American culture, including American language, music, dance, and cuisine.[64] The first Africans carried from Angola may have brought some Christian practices that they learned from the Portuguese Catholic missionaries and Jesuit priests in Africa.[65]

Enslaved African Americans fostered racial pride, groomed their children, and taught life lessons by the telling of stories from African folklore, as well as African parables and proverbs. The animal characters in these stories represent human traits—for example, tortoises represent tricksters, while other animal figures employ guile and intelligence to get the better of powerful enemies.[38]

Religion and music

White people built and held religious services in church buildings where free blacks and enslaved people may also have been allowed to worship, albeit in segregated spaces, until they were able to establish their own churches.[66]

Some enslaved persons were able to attend church and others met secretly in the woods to worship. Either way, religious practices—such as music, call-and-response forms of worship, and funeral customs—helped blacks preserve their African traditions and manage "the dehumanizing effects of slavery and segregation".[38]

Methodist and Baptist ministers preached sermons on redemption and hope to enslaved blacks, who introduced shouts and the singing of sorrow songs to religious ceremonies, creating their own religious music that incorporated complex rhythms, foot-tapping, and off-key vocalizations with European practices. They sang communal songs called spirituals about deliverance, salvation, and resistance[38]

Music was an important part of the social fabric of African American communities. Work songs and field hollers were used on plantations to coordinate group tasks in the fields, while the singing of satirical songs was a form of resisting the injustices of slavery.[38]

Food

Enslaved people's diet was determined by what food was given to them, the mainstays being corn and pork.[38][67] At hog butchering time, the best cuts of meat were kept for the master's household and the remainder, such as fatback, snouts, ears, neck bones, feet, and intestines (chitterlings) were given to the slaves. Cornbread was commonly eaten by enslaved people, and there were many other ways that corn was prepared, such as porridge, hominy, grits, corn cakes, waffles, and corn dodgers.[68] Enslaved adults were typically given a peck (9 liters) of cornmeal and 3–4 pounds (1.5–2 kilos) of pork per week, and from those rations come soul food staples such as cornbread, fried catfish, chitterlings, and neckbones.[69]

Enslaved Africans augmented their rations with cooked greens (collards, beets, dandelion, kale, and purslane) and sweet potatoes.[70] Excavations of slave quarters found that their diet included squirrel, duck, rabbit, opossum, fish, berries and nuts.[67][68] Vegetables and grain included okra, turnips, beans, rice, and peas.[67][71]

Similarly to the ways in which early Virginians shared knowledge and traditions of their heritage with one another,[8] enslaved people prepared meals based upon European, indigenous, and African cuisines, devising their own cookery from the limited rations given to them by their masters. They prepared gumbo, fricassee, fried foods,[38] and soups made from scraps of meat and vegetables;[67] thus originating what is now called soul food;[69] these foods were cooked in their fireplaces.[67]

According to Booker T. Washington, who grew up on a tobacco plantation in Virginia, scraps were often the only food available to enslaved persons. If there was nothing for breakfast, he ate boiled Indian corn that was prepared for the pigs. If he did not get to it before the pigs were fed, he picked up pieces around the pig troughs.[67] He remembers as a young boy being awakened to eat a chicken acquired by his mother, likely taken from the plantation, and cooked in the middle of the night.[67]

How or where she got it I do not know. I presume, however, it was procured from our owner's farm. Some people may call this theft. But taking place at the time it did, and for the reason it did, no one could ever make me believe that my mother was guilty of thieving. She was simply a victim of the system of slavery.

Clothing

The clothing that enslaved people in Virginia wore varied depended upon when they lived, what occupations they had, and the practices of their enslavers. They could not retain their choice of clothing from Africa, except that some women wore traditional West African cloth head wraps.[72] In the eighteenth century, if they worked in the fields, they likely wore uncomfortable, simple European-style clothing. It was certainly made of inexpensive and inferior fabric, like Negro cloth and osnaburg made from hemp and flax. Some people found the clothing so uncomfortable that they tried to take it off when able.[72]

More durable and comfortable fabric, like jean cloth, was used in the nineteenth century. With increased cotton production, ready-made clothing of blended fabrics was common. If someone worked in the house or held a liveried position, they had higher quality clothing or uniforms. Girls wore simple gowns and then adult dresses beginning in puberty. Boys clothing varied as they aged. They wore simple gowns, short pants, and then long pants. They were given shoes and sometimes hats. Clothing was generally handed out twice a year. Personal touches could be applied in the making of vegetable-dyed fabrics, sewn-on glass beads or cowrie shells, or hand-fashioned necklaces. Some people planning to run away acquired better clothing, so that they would be less conspicuous—they stole clothing or purchased it, if they were able to make money.[72]

Slave trade

Transatlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade started in the sixteenth century when Portuguese and Spanish ships transported enslaved people to South America, and then to the West Indies. Virginia became part of the Atlantic slave trade when the first Africans were brought to the colony in 1619.[73] The slaves were sold for tobacco and hemp that was sent to Europe.[73]

In 1724, one merchant, Richard Merriweather, speaking on behalf of Bristol merchants concerning the 1723 act passed in Virginia that imposed a duty on liquor and slaves, estimated that between 1500 and 1600 slaves were imported to Virginia each year by Bristol and London merchants.[74] In 1772, prominent Virginians submitted a petition to the Crown, requesting that the slave trade to Virginia be abolished; it was rejected.[75][76][77]

The United States Congress enacted an Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves that was effective as of 1808. This increased the domestic slave trade business.[38]

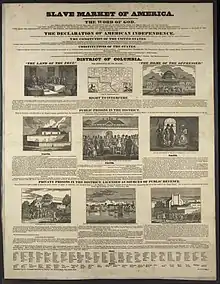

Domestic slave trade and breeding

.jpg.webp)

Virginia's domestic slave trade grew substantially in the early nineteenth century. It became the state's most lucrative industry, with more money being made by the exporting of enslaved people than was made from tobacco.[38] Women were used for breeding. White men had sex with enslaved women at will, consequently they could obtain more slaves to breed field workers, giving them an incentive to provide health care that would ensure women's fertility and successful childbirth. Two million enslaved people are believed to have been transported or marched on foot from Richmond to the Deep South, where they were needed to labor in the cotton fields.[38] Robert Lumpkin operated his slave jail, where enslaved blacks suffered greatly under his brutal management, near the slave market of Richmond, which city was the largest American slave-trading center after New Orleans,[78] and ranked first in slave breeding.[79]

Enslaved women and girls were raped by their enslavers and enslaved men to reproduce and birth more slaves for the slave market and more slaves for slaveholders. According to historian Wilma King writing in The Journal of African American History, "...[T]here is evidence that some enslaved men were coerced into sexual relations with enslaved women by slave owners leading to rape, or that bondmen sexually abused black girls and women over whom they exercised authority." She cites the case of an enslaved female teenager who was forced to lie with a male slave, but whose voyeuristic enslaver was more interested in watching them have sex at his command than in increasing his stock of enslaved persons.[80]

Sale

Richmond was a hub and the largest seller of enslaved people in Virginia.[81][11] When enslaved people were sold, it meant that communities and families were subject to being dispersed to different places.[81] It was common for people to be separated from their spouses and children, perhaps for the rest of their lives.[81] People were taken from the plantation and put into jails or slave pens of slave traders. They might be held there for weeks and were subject to intrusive physical inspections. When they were auctioned, they could be sold again to another trader or ultimately sold to work on plantations in the Lower South.[81]

The sale prices for enslaved people varied based upon age, gender, and the time period. Women were valued at eighty or ninety per cent of the prices men would bring. Children were valued at about half the value of a "prime male field hand". In the late 1830s, the high rate for an enslaved person was $1,250, due to a boom in the cotton industry. In the 1840s, the value dipped substantially, and recovered in the late 1850s, when the highest value for an enslaved person reached about $1,450.[38]

Alexandria was a center of the slave trade, and was situated on land ceded by Virginia to the US federal government to create the federal district. That land was returned to Virginia with the District of Columbia retrocession. Once again a part of Virginia, Alexandria's slave trading business was secure. One of the main reasons that the retrocession occurred was that the end of slavery in the District of Columbia was a primary goal of abolitionists, a goal staunchly opposed by slave owners and slave traders, who endeavored to protect their business interests and therefore desired Alexandria to be in slave-holding territory.[82]

Controls and resistance

Slaveholders had ongoing concerns that bondspeople might run away or revolt against them, and employed a number of controls. One tactic was to prevent African Americans from learning how to read and write. They limited opportunities for groups of people to meet and prevented them from leaving the plantation. Slaves who attempted to escape their bondage and were caught were punished publicly; punishments included execution and physical disfigurement. White Virginians who helped black people violate the codes were also punished. Other control tactics were incentives, religion, the legal system, and intimidation.[38]

There were various ways the enslaved could resist their servitude, but the most effective means was by having their own culture, expressed through religion, music, folklore, and music. Other means included working at a slow pace, stealing food, or breaking the slaveholder's property. Even though the risks were well-known, some people still tried to escape when they could.[38]

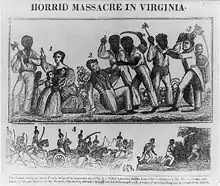

Revolts

During the nineteenth century, there were three major attempted slave revolts in Virginia: Gabriel's Rebellion in 1800, Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831, and John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, organized by a white radical abolitionist, John Brown. After Nat Turner's rebellion, thousands of Virginians sent the legislature over forty petitions calling for an end to slavery, and Richmond's newspapers argued fiercely for abolition.[83][84] According to historian Eva Sheppard Wolf, "The response of white Virginians continued well beyond their initial fit of violence and included the most public, focused, and sustained discussion of slavery and emancipation that occurred in the commonwealth or any other southern state."[85] About a third of the petitions received by the House of Delegates also called for the prior forced exile of all free Blacks from Virginia to Liberia.[86] Free Blacks, at least by 1859, were barred from entering the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Thomas Jefferson's grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph,[87] led the losing faction in the Virginia legislature. Their proposed bill would have freed all children born of slave parents after July 4, 1840.[88] Thomas R. Dew opposed it; his book, Review of the Debate in the Virginia Legislature,[89] was influential in its defeat.[90] It failed by one vote.

Freedom

Opportunities for most enslaved African Americans to attain freedom were few to none. Some were freed by their owners to honor a pledge, to grant a reward, or, before the 1700s, to fulfill a servitude agreement. A few were bought by Quakers, Methodists, and religious activists for the sole purpose of freeing them (a practice soon banned in the southern states). Many ran away to free territory, and some of these "fugitives" succeeded in avoiding capture and forced to the South.

—Buying One's Freedom, Emancipation of Enslaved African Americans, African American Identity [91]

There were many enslaved people who attained freedom before the American Civil War. Some were freed, or voluntarily emancipated by their slaveholder through manumission. Regulation of manumission began in 1692, when Virginia established that to manumit a slave, a person must pay the cost for them to be transported out of the colony. A 1723 law stated that slaves may not "be set free upon any pretence whatsoever, except for some meritorious services to be adjudged and allowed by the governor and council".[92][93] The new government of Virginia repealed the laws in 1782 and declared freedom for slaves who had fought for the colonies during the American Revolutionary War of 1775–1783. The 1782 laws also permitted masters to free their slaves of their own accord; previously, a manumission had required obtaining consent from the state legislature, which was arduous and rarely granted.[94] Rarely after 1800, some people were able to purchase their own freedom.[95] As the abolition movement grew in popularity, more people were freed.[95]

Many of the free blacks were highly skilled. Some were tailors, hair stylists, musicians, cooks, and artisans. Others were educators, writers, business people, planters, and cooks.[95] Notable freed persons include Absalom Jones, abolitionist and clergyman; Richard Allen, minister, educator, and writer; Sarah Allen, abolitionist, missionary, and wife of Richard Allen; Frederick Douglass, orator, writer, and statesman; and Harriet Tubman, abolitionist and political activist. Thomas L. Jennings invented a dry-cleaning method for clothes, while Henry Blair was a scientist who patented a seed planter.[95]

Free blacks were on average older than the general population of slaves. This was partly because slaveholders were likely to free blacks once they developed disabilities or other health issues that come with age. If they were going to buy their freedom, enslaved people had to build up savings to make up the asking price. Children of white enslavers were more likely to be treated favorably and obtain their freedom. Skilled free blacks of mixed race were a large portion of the freed slaves.[96]

Indentured servitude

Indentured servitude was a contractual arrangement between English persons and their masters that specified the number of years to be worked in exchange for their passage to Virginia and their upkeep. One of the restrictions of their contracts was that they could not marry while in service. The first servants who came to Virginia received a percentage of the profits of the Virginia Company of London. After ten years, in an attempt to attract more workers, English indentured servants were to receive land upon the completion of their contract. Servants and their masters could take one another to court if the terms of the contract were not being met or to address wrongs, such as physical abuse of the servant.[97][98]

From the start, Africans were not treated the same as English indentured servants.[97] White indentured servants were recorded in early muster (census) records with their date of arrival, surnames, and marital status. Blacks were listed by only their first names, if their names were listed at all.[99] Records survive in Virginia of seven cases brought by Africans or African Americans asserting that they had served finite terms of servitude and had earned freedom, as if indentured, but their masters claimed they were bound to service for life. Six of these suits failed, indicating that the Virginia courts regarded Africans and African Americans as enslaved for life rather than bound to specific terms of indenture.[100]

One of the first Africans to come to Virginia and subsequently be freed was Anthony Johnson, who then held a contract with John Casor as an indentured servant. Casor fulfilled their agreed-upon arrangement, and worked another seven years. They went to court, and the judge determined that Casor was to be his slave for the rest of his lifetime.[101][102][lower-alpha 12] Philip Cowen had worked the agreed upon number of years as a servant and expected to be freed. Like other blacks, he was forced to sign a document that extended his service. Charles Lucas "with threats and a high hand and by confederacy with some other persons" forced him to sign an indenture document. He filed a lawsuit with the court in 1675 and after winning the case was given a new suit of clothes and three barrels of corn, as he had been promised while in service.[105][106]

In an unusual court case, John Graweere, an indentured servant, filed a petition to purchase his son. The boy was born to an enslaved woman. Graweere wanted to raise him as a Christian. The court ruled in 1641 in his favor and he was able to free his son.[107][108]

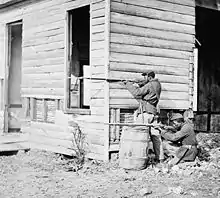

Run away

.jpg.webp)

Another way to attain one's freedom was to run away, which made that person a fugitive slave.[109] Both indentured servants and enslaved people ran away for several reasons. They may have been in search of family members that they were separated from, or fleeing abusive masters and hard labor.[110]

Slaves from Virginia escaped via waterways and overland to free states in the North, some being aided by people who lived along the Underground Railroad, which was maintained by both whites and blacks.[109] Although there were a number of measures to control enslaved people, there were still many that ran away. In doing so, they had to cross wide rivers or Chesapeake Bay, which was subject to storms that made the passage more difficult. People often headed for Maryland and places further north such as New York and New England, and may have encountered hostile Native Americans along the way.[110]

.tif.jpg.webp)

In 1849, slave Henry "Box" Brown escaped from slavery in Virginia when he arranged to be shipped by express mail in a crate to Philadelphia,[109] arriving in little more than 24 hours.[111]

There were at least 4,260 notices of runaway slaves published in Virginia from 1736 to 1803.[112] Those persons who helped apprehend runaways were given the stipulated cash award; advertisements were also often placed in newspapers when the fugitives were captured.[113] If slaves ran away a number of times and were returned to the slaveholders, they might be branded, shackled, or have their hair cut in an identifiable way.[110]

Sometimes, black and whites ran away together, with far different repercussions. In 1643, the Virginia General Assembly passed laws about runaway servants and slaves.[110] In 1660, the Assembly stated that "in case any English servant shall run away in company with any Negroes who are incapable of making satisfaction by addition of time…[he] shall serve for the time of the said Negroes absence."[114] An act concerning Servants and Slaves of 1705 allowed for severe punishment of slaves, to the point of killing them. There were no consequences for excessive punishment or for killing slaves after this law was passed.[110]

Self-purchase or family members's purchase of freedom

Another path to freedom was to purchase it by saving one's wages. In 1839, over forty percent of the free blacks in Cincinnati, Ohio, had paid for their freedom. Moses Grandy, born in North Carolina but who worked in Virginia, purchased his freedom twice.[115] If a former slave wanted to purchase the freedom of his wife and children, he had to persuade the slaveholder to allow the purchase of family members, which could take years. If terms were agreed upon, a price was set. The arrangement could be broken if the slaveholder died before the wife or children were freed.[116]

Mary Hemings, an enslaved woman from Thomas Jefferson's Monticello plantation, and two of her children, were purchased by her common-law husband, Thomas Bell. She was unable to purchase her two oldest children, Betsy Hemmings and Joseph Fossett, who was later freed in accordance with Thomas Jefferson's will. His wife Edith Hern Fossett and her children were not freed.[117] Joseph and his brother-in-law Jesse Scott purchased the freedom of Edith and their children.[118] Also from Monticello, Israel Jefferson purchased his freedom with his wife's assistance. Peter Hemmings was purchased by a family member and then was freed. Mary Colbert's freedom was obtained by family members.[119]

Freedom suit

In 1658, Elizabeth Key was the first woman of African descent to bring a freedom suit in the Virginia colony. She sought recognition as a free woman of color, rather than being classified as a Negro (African) and slave. Her natural father was an Englishman (and member of the House of Burgesses). He acknowledged her, had her baptized as a Christian in the Church of England, and arranged for her guardianship under an indenture before his death.[45] Before her guardian returned to England, he sold Key's indenture to another man, who held Key beyond its term. When he died, the estate classified Key and her child (also the natural son of an English subject) as Negro slaves. Key sued for her freedom and that of her infant son, based on their English ancestry, her Christian status, and the record of indenture. She won her case.[45]

Manumission

Some enslaved people were manumitted by their enslavers.[116] In some cases, people were freed because they were held in good esteem by their enslavers, sometimes it was because the enslaved were no longer useful. In other cases, mixed-race children of white slaveholders were freed.[95]

White residents of Virginia found freed blacks to be a "great inconvenience" and were suspicious of their ability to influence enslaved people and accused them of crimes. So laws were passed to make it more inconvenient for the blacks and their enslavers.[116] In 1691, a law was passed that required freedmen to leave the colony and required former slaveholders to pay for their transportation. In 1723, a law was passed that made it harder to free slaves:[116]

No negro, mullatto, or Indian slaves, shall be set free, upon any pretence whatsoever, except for some meritorious services, to be adjudged and allowed by the governor and council, for the time being, and a licence thereupon first had and obtained.[116]

Those slaves who were freed could be sold back into slavery if enough people complained about them. In the early years of the colony's history, "meritorious service" meant that slaves should alert authorities if there were plans of rebellion. Later, it was construed to mean faithfulness or exemplary character.[116]

In the first two decades after the American Revolutionary War, inspired by the Revolution and evangelical preachers, numerous slaveholders in the Chesapeake region manumitted some or all of their slaves, during their lifetimes or by will.[120] In 1782, it was made easier to manumit enslaved blacks, but if they were more than 45 years of age, the former slaveholder may have been responsible for providing them an income if they were unable to work.[116] In 1806, freed slaves were to leave the state after one year of freedom.[121]

From 1,800 persons in 1782, the total population of free blacks in Virginia increased to 12,766 in 1790, about four percent of the state's total number of blacks, and to 30,570 in 1810. The percentage change was from free blacks comprising less than one percent of the total black population in Virginia, to 7.2 percent by 1810, even as the overall population increased.[120] One planter, Robert Carter III, freed more than four hundred and fifty slaves beginning in 1791, more than any other planter.[122][123] George Washington freed all of his slaves at his death.[124][125]

Immigrants

Free blacks came to the Southern states after the 1791 Haitian slave revolt in Saint-Domingue, in which enslaved blacks fought the French. Some of the free blacks brought their slaves with them, and many more slaves and free people of color arrived in Louisiana after the United States purchased Louisiana,[126] and joined the generally mixed-race issue of black slaves and French and Spanish colonists.[127][96]

Life after attaining freedom

Settlement

Most free people of color lived in the American South, but there were freed people who lived throughout the United States. According to the US census of 1860, 250,787 of them lived in the South[128] and 225,961 lived in other parts of the country. In 1860, the free blacks were one hundred percent of the population of blacks in the north.[96] Large populations of free blacks lived in Philadelphia, Virginia, and Maryland.[95]

In the south, free blacks only made up about six percent of blacks there. Generally, women were more likely to stay in Virginia and men were more likely to head north.[96][129] Of those who stayed, they generally moved to cities, where work was easier to find.[96] Many freed people and runaways lived in the Great Dismal Swamp maroons of Virginia.[130] Those who lived in western Virginia became West Virginians in 1863. Even throughout the American Civil War, black Virginians were more likely to stay in the state.[96]

Education

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

African Americans established schools, including secondary schools, for freed people in Virginia soon after the start of the American Civil War (1861–1865).[131] The schools were taught by white and black teachers, the latter of whom taught longer than whites throughout Reconstruction.[131]

The federal government provided supplies to build schools through the Freedmen's Bureau and transported teachers to Virginia. American Missionary Association and other aid societies sent teachers, as well as books and supplies. Evidence "suggests that black education in Virginia, as elsewhere in the South, was a product of the freed people's own initiative and determination, temporarily supported by northern benevolence and federal aid."[131]

Religion

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, which grew out of the Free African Society, was founded by Richard Allen in Philadelphia.[132][133] It was central to communities of free African Americans, and branched out to Charleston, South Carolina, and other areas in the South, although there were laws that prevented blacks from preaching. The church was treated brutally by whites and members were arrested en masse.[95]

Inequities

Freedom had its challenges. There were laws, particularly in the Upper South, that created obstacles for free blacks. Lawmakers sought to keep an eye on free blacks, by registering them, deporting them, or putting them in jail. They made it harder for black to testify in court and to vote. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. cites a quote by Ira Berlin of a common saying at the time: "even the lowest whites [could] threaten free Negroes … with 'a good nigger beating.'"[96]

Anthony Johnson was an African who was freed soon after 1635; he settled on land on the Eastern Shore following the end of indenture, later buying African indentured servants as laborers.[134] Although Anthony Johnson was a free man, on his death in 1670, his plantation was given to a white colonist, not to Johnson's children. A judge had ruled that he was "not a citizen of the colony" because he was black.[102][lower-alpha 13]

Civil War

The American Revolutionary War of 1776 and the Constitution of 1787, left open the issues of whether aristocrats or other groups of people should reign over others. Americans were proud to say that America was "the land of liberty, a beacon of freedom to the oppressed of other lands" in the early 1800s. However, the United States had become the largest slaveholding country in the world by the 1850s.[136] From 1789 to 1861, two thirds of the country's various presidents, nearly three fifths of its Supreme Court justices, and two thirds of its Speakers of the House were slaveholders. There was growing tension between the Southern plantation society based upon slave labor and "diversified, industrializing, free-labor capitalist society" in the North.[136] Richmond, Virginia was the site of the Confederate capital.[5]

In June 1861, enslaved people traveled with their families to Union camps, including Fort Monroe, where they thought that they would be free. They ended up, however, working very hard in difficult, unsanitary conditions. They didn't have an enslaver to deal with, but they were treated similarly by the military.

During the Civil War, free blacks worked as cooks, teamsters, and laborers. They also worked as spies and scouts for the United States military.[137] Starting in 1863, approximately 180,000 African Americans joined the United States Colored Troops and fought for the Union Army;[138] there was no Confederate equivalent. A growing number of white soldiers began to see the need to end slavery and for a united country. Constant Hanks, a private in the New York State Militia, wrote in a letter to his father after the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863: "Thank God... the contest is now between Slavery & Freedom, & every honest man knows what he is fighting for."[139][140]

Booker T. Washington, born enslaved on the Burroughs plantation in Franklin County, Virginia, later described the food shortages that resulted from the Union blockades during the Civil War and how it affected the owners much more than it did the slaves. The owners had grown accustomed to eating expensive items before the war, while the scarcity of these items had little impact on the slaves.[67]

.jpg.webp)

Thousands of enslaved people went to Harpers Ferry, Virginia, a garrison town behind Union lines, so as to be protected; these individuals were called contrabands.[141][137] The protection was only as secure as the Union lines; when the Confederates retook Harpers Ferry in 1862, hundreds of contrabands were captured.[137]

The end of slavery in Virginia

Slave trading until the defeat of the Confederacy, but the economic uncertainty wrought by the conflict had a negative impact that was immediately visible in Richmond, according to one 1861 newspaper report:[142]

Business of every kind, not necessarily connected with the war, is entirely Prostrated. Negro trading is at an end, and will never be revived, unless the South is victorious. The slave prisons are empty, and the long line of slave auction rooms in Franklin street, heretofore thronged with able men, women, and children, and the detested rough and vulgar nigger traders, now present the aspect of a quiet and deserted street. The Richmond nigger traders were the first to embrace Secession—they contributed the first to the cause, and the first Secession flag in that city appeared from the window of one of their auction rooms.[142]

The first concrete, successful step towards ending slavery in Virginia was President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, effective January 1, 1863.[136] However, it applied only to those areas controlled by the Union Army; Charlottesville commemorated the arrival of Union troops on March 3, 1865, bringing with them freedom for everyone enslaved, with its new Liberation and Freedom Day holiday.[143] The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, effective December 18, 1865, made slavery illegal everywhere in the country.[144]

Historic reckoning

Education about the history of slavery in the United States tends to blur the truth of horrors that enslaved people experienced, including sexual violence, being separated from family members, as well as the physical and psychological cruelty they experienced. Schoolbooks tend to skim the surface of slavery.[145] Historians, civil rights advocates, and educators recommend changing the way that slavery is taught in schools and acknowledging how misconceptions, soft-pedaling, and denial impacts the lives of Africans into the 21st century, including fewer opportunities, the greater likelihood of African Americans to be put in prisons, and becoming victims of hate crimes.[145]

In 2007, the Virginia General Assembly approved a formal statement of "profound regret" and acknowledgement of the "egregious wrongs" committed against African Americans. Part of the statement is:[11]

The General Assembly hereby expresses its profound regret for the Commonwealth's role in sanctioning the immoral institution of human slavery, in the historic wrongs visited upon native peoples, and in all other forms of discrimination and injustice that have been rooted in racial and cultural bias and misunderstanding...

— Virginia General Assembly[11]

The statement was made in May 2007 to coincide with the 400 year anniversary of the first Virginian settlers arriving at Jamestown.[81]

The place where the First Africans landed is now the site of Fort Monroe. In 2011, President Barack Obama read a proclamation: "The first enslaved Africans in England's colonies in America were brought to this peninsula on a ship flying the Dutch flag in 1619, beginning a long ignoble period of slavery in the colonies and, later, this Nation." The fort was made a National monument.[146][147]

Education about the history of slavery in Virginia has remained a contentious issue into the 2020s, with governor Glenn Youngkin opposing Critical Race Theory and accused of "watering down Black history".[148]

See also

- Atlantic Creole

- Bristol slave trade

- Coastwise slave trade

- Colonial South and the Chesapeake

- First Africans in Virginia

- Great Dismal Swamp maroons

- History of slavery in the United States by state

- Human trafficking in Virginia

- Indentured servitude in Virginia

- Liberation and Freedom Day

- List of plantations in Virginia

- Memorial to Enslaved Laborers

- Scramble (slave auction)

- Seasoning (slavery)

- Slavery in the colonial history of the United States

- Tobacco colonies

- Virginia in the American Civil War

Notes

- ↑ In May 1623, English men met with Opchanacanough to negotiate peace and the release of the women.[17] Captain Tucker and a group of musketeers met with Opechancanough and members of a Powhatan village along the Potomac River on May 22. Captain Tucker and others offered ceremonial toasts and 200 Powhatan died after drinking wine the English had poisoned. The English killed another 50 Indians.[17][20]

- ↑ Virginia institutionalized slavery, but it was not the site of the first African arriving in the North American continent. The first documented black person to arrive on the continent was Juan Garrido, who traveled with Juan Ponce de León to Florida in 1513.[22] The first enslaved people in the northern hemisphere landed with the Spanish near St. Augustine in 1565.[23]

- ↑ Soon after the founding of Virginia as an English colony by the London Virginia Company. The company established a headright system to encourage colonists to transport indentured servants to the colony for labor; they received a certain amount of land for people whose passage they paid to Virginia.[32]

- ↑ In one example from 1640, Robert Sweet impregnated a black woman. He was to do penance in church; the pregnant woman was to be whipped. Laws enacted in the seventeenth century sought to define the rights and obligations of indentured servants. The laws for black people and Native Americans limited their rights. If a black person ran away with a white servant, laws stipulated that owners would be compensated for the loss of the enslaved person's work. The servant was expected to work without pay the number of days that the enslaved person was away.[33] Another law stipulated that if an enslaved person was killed, the owner was to be compensated with four thousand pounds of tobacco.[33]

- ↑ Early cases show differences in treatment between Negro and European indentured servants. In 1640, the General Virginia Court decided the Emmanuel case. Emmanuel was a Negro indentured servant who participated in a plot to escape along with six white servants. Together they stole corn, powder, and shot guns but were caught before making their escape. The members of the group were each convicted; they were sentenced to a variety of punishments. Christopher Miller, the leader of the group, was sentenced to wear shackles for one year. White servant John Williams was sentenced to serve the colony for an extra seven years. Peter Willcocke was branded, whipped, and was required to serve the colony for an additional seven years. Richard Cookson was required to serve for two additional years. Emmanuel, the Negro, was whipped and branded with an "R" on his cheek.[37]

- ↑ African Americans cooked the students' meals, cleaned their rooms, washed their clothes, and maintained campus school buildings, dormitories, and outhouses. Assigned students to look after, they ran errands within Charlottesville, managing competing requests and schedules, these enslaved people were subject to harsh treatment and pranks while other white students watched and laughed.[43]

- ↑ The young men would have been treated more harshly if they mishandled a library book. After a comprehensive review of archival records at the University of Virginia completed in 2018, it was found that "in every way imaginable... [rape and abuse were] central to the project of designing, funding, building, and maintaining the school."[43]

- ↑ English common law held that among English British subjects, a child's status was inherited from its father. The community could require that the father recognize illegitimate children and support them.

- ↑ English common law held that among British subjects, a child's social status was inherited from its father. Thus, the community could require that the father recognize illegitimate children and support them.

- ↑ By 1860, Virginia had a black population that numbered about 550,000; only 58,042 or slightly more than ten percent were free people of color. In Cuba by contrast, there were 213,167 free people of color, or about forty per cent of its black population of 550,000.[60] Cuba had not developed a plantation system in its early years, and its economy supported the Spanish empire from urbanized settlements.

- ↑ By the mid-eighteenth century, there were 145,000 slaves in the Chesapeake Bay region,[52] as compared to 50,000 in the Spanish colony of Cuba, where they worked in urbanized settlements; 60,000 in British Barbados; and 450,000 in the French plantation colony of Saint-Domingue.[60]

- ↑ By the 1650s, Johnson and his wife Mary were farming 250 acres in Northampton County, Virginia while their two sons owned 450 acres and 100 acres, respectively.[103][104]

- ↑ In 1677, Anthony and Mary's grandson, John Jr., purchased a 44-acre farm which he named Angola. John Jr. died without leaving an heir, however. By 1730, the Johnson family had vanished from the historical records.[135]

References

- ↑ "America and West Indies: September 1672." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 7, 1669–1674. Ed. W Noel Sainsbury. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1889. 404–417. British History Online. Web. 31 May 2021. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol7/pp404-417.

- ↑ R. Kent Rasmussen; Salem Press (2000). American Indian Tribes: Tribes and traditions: Miwok. Salem Press. p. 436. ISBN 978-0-89356-065-2.

- ↑ Margaret Holmes Williamson (January 1, 2008). Powhatan Lords of Life and Death: Command and Consent in Seventeenth-Century Virginia. University of Nebraska Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-8032-6037-5.

- ↑ Joseph Kelly (October 30, 2018). Marooned: Jamestown, Shipwreck, and a New History of America's Origin. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 350. ISBN 978-1-63286-779-7.

- 1 2 3 Jesse J. Holland (7 February 2019). "Researchers seek fuller picture of first Africans in America". AP NEWS. AP. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Indian Enslavement in Virginia". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- 1 2 "African Americans at Jamestown". National Park Service. Retrieved 2021-05-14.

- 1 2 3 Seaman, Catherine H. C. (1992). Tuckahoes and Cohees: The Settlers and Cultures of Amherst and Nelson Counties, 1607–1807. Sweet Briar College. p. 1.

- 1 2 3 Worsham, Gibson (2003). "A Survey of Historic Architecture in Goochland County, Virginia" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. pp. 13, 22–23.

- 1 2 3 National Geographic Society (June 20, 2019). "The Plantation System". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2021-05-14.

Throughout the New World, the plantation served as an institution in itself, characterized by social and political inequality, racial conflict, and domination by the planter class.

- 1 2 3 4 Craig, Tim (February 3, 2007). "In Va. House, 'Profound Regret' on Slavery". Washington Post.

- 1 2 3 "The History". Historic Tuckahoe. March 4, 2013. Retrieved 2021-05-03.

- ↑ Eckenrode, H. J. (Hamilton James) (1946). The Randolphs: the story of a Virginia family. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Stone, Meredith; Spangler, Ian; Griffin, Xavier; Hanna, Stephen P. (2016). "Searching for the Enslaved in the "Cradle of Democracy": Virginia's James River Plantation Websites and the Reproduction of Local Histories". Southeastern Geographer. 56 (2): 207. ISSN 0038-366X. JSTOR 26233788.

- ↑ "As plantations talk more honestly about slavery, some visitors are pushing back". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2021-05-14.

- ↑ Michael Guasco (January 11, 2014). Slaves and Englishmen: Human Bondage in the Early Modern Atlantic World. University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8122-0988-4.

- 1 2 3 "Powhatan Uprising of 1622". HistoryNet. June 12, 2006. p. 190. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ↑ Jack D. Forbes (March 1993). Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples. University of Illinois Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-252-06321-3.

- ↑ Richard S. Dunn (December 1, 2012). Sugar and Slaves: The Rise of the Planter Class in the English West Indies, 1624-1713. UNC Press Books. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8078-9982-3.

- ↑ "Timeline". Historic Jamestowne.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Virginia's First Africans". www.encyclopediavirginia.org. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ↑ Jane Landers (1999). Black Society in Spanish Florida. University of Illinois Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-252-06753-2.

- ↑ Junius P. Rodriguez (2007). Slavery in the United States: A Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 287. ISBN 978-1-85109-544-5.

- ↑ "Angela (fl. 1619–1625) – Encyclopedia Virginia". 2021-05-28. Archived from the original on 2021-05-28. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- 1 2 "In 1619 enslaved Africans first arrived in colonial Virginia. Here's the history". National Geographic. August 13, 2019. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved 2021-05-12.

- ↑ Wade, Evan (April 16, 2014). "William Tucker (1624- ?)". Retrieved 2021-05-14.

- 1 2 "Indentured Servants in Colonial Virginia". www.encyclopediavirginia.org. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ↑ Austin, Beth (December 2019). "1619: Virginia's First Africans". Hampton government site. pp. 18, 20. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ↑ Austin, Beth (December 2019). "1619: Virginia's First Africans". Hampton government site. p. 17. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ↑ Austin, Beth (December 2019). "1619: Virginia's First Africans". Hampton government site. pp. 14, 20. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ↑ Coates (2003). "Law and the Cultural Production of Race and Racialized Systems of Oppression" (PDF). American Behavioral Scientist. 47 (3): 332–333. doi:10.1177/0002764203256190. S2CID 146357699.

- ↑ Hashaw, Tim (2007). The Birth of Black America. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. pp. 76–77, 211–212, 239–240. ISBN 978-0-7867-1718-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rose, Willie Lee Nichols (1999). A Documentary History of Slavery in North America. University of Georgia Press. pp. 15–22, 25. ISBN 978-0-8203-2065-6.

- ↑ Austin, Beth (December 2019). "1619: Virginia's First Africans". Hampton government site. pp. 18, 20. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ↑ "Colonial Virginia". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 2021-05-12.

- ↑ John Donoghue (September 15, 2010). "Child Slavery and the Global Economy: Historical Perspectives on a Contemporary Problem". In James Garbarino; Garry Sigman (eds.). A Child's Right to a Healthy Environment. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-4419-6791-6.

- ↑ Higginbotham, A. Leon (1975). In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process: The Colonial Period. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-19-502745-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 "Slavery". Virginia Museum of History & Culture. Retrieved 2021-05-12.

- ↑ "Slavery at Monticello FAQs- Work". Monticello. Retrieved 2021-05-14.

- ↑ Harper, C. W. (1978). "House Servants and Field Hands: Fragmentation in the Antebellum Slave Community". The North Carolina Historical Review. 55 (1): 55. ISSN 0029-2494. JSTOR 23535381.

- ↑ Michael L. Levine (1996). African Americans and Civil Rights: From 1619 to the Present. Oryx Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-89774-859-9.

- 1 2 Kennedy, Randall (January 26, 2003). "'Interracial Intimacies'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-05-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Two centuries ago, University of Virginia students beat and raped enslaved servants, historians say". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2021-05-14.

- ↑ Ervin L. Jordan (1995). Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia. University of Virginia Press. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-0-8139-1545-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Taunya Lovell Banks, "Dangerous Woman: Elizabeth Key's Freedom Suit -Subjecthood and Racialized Identity in Seventeenth Century Colonial Virginia", 41 Akron Law Review 799 (2008), Digital Commons Law, University of Maryland Law School, accessed 21 Apr 2009

- ↑ "Sally Hemings | Life of Sally Hemings". www.monticello.org. Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

She was three-quarters-European and one-quarter African. In two separate censuses taken near the end of her life, Hemings's race is recorded as white in one and as mulatto in the other, hinting at shifting notions of her identity. Of her surviving children, who were 7/8 European and 1/8 African, three passed as white and one identified as black.

- ↑ Newby-Alexander, Cassandra L. (2020). "The 'Twenty and Odd': The Silences of Africans in Early Virginia Revealed". Phylon. 57 (1): 25–36. ISSN 0031-8906. JSTOR 26924985.

- 1 2 Warren M. Billings (1975). "Bound Labor: Slavery". In Warren M. Billings (ed.). The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century: A Documentary History of Virginia, 1606–1689. UNC Press Books. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8078-1237-2.

- ↑ Peter Kolchin (2003). American Slavery: 1619–1877. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8090-1630-3.

- 1 2 Beverley, Robert (1705), Of the Servants and Slaves in Virginia (PDF), National Humanities Center, pp. 3–4

- ↑ Flanigan, Daniel J. (1974), "Criminal Procedure in Slave Trials in the Antebellum South", The Journal of Southern History, 40 (4): 543–544, doi:10.2307/2206354, JSTOR 2206354

- 1 2 Klein, Herbert S. (2010). The Atlantic slave trade (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-521-18250-8. OCLC 662453011.

- ↑ Austin, Beth (December 2019). "1619: Virginia's First Africans". Hampton government site. p. 21. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ↑ CG Woodson (April 1916). "Freedom and Slavery in Appalachian America" (PDF). The Journal of Negro History. The University of Chicago Press. 1 (2): 133–135. doi:10.2307/3035635. JSTOR 3035635. S2CID 150041667. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- 1 2 "Political Decline and Westward Migration". Virginia Museum of History & Culture. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- ↑ Sukari Ivester (20 September 2018). "Economics and Work: Slavery, Urban and Industrial". In Alexandra Kindell (ed.). The World of Antebellum America: A Daily Life Encyclopedia [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 169–171. ISBN 978-1-4408-3711-1.

- ↑ Alton Hornsby (31 August 2011). Black America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 920. ISBN 978-0-313-34112-0.

- ↑ Thomas Condit Miller; Hu Maxwell (1913). History of West Virginia.- v. 2–3. Family and personal history. Lewis Historical Publishing Company. p. 186.

- ↑ "Slavery in western Virginia". www.wvculture.org. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- 1 2 Melvin Drimmer, "Reviewed Work: Slavery in the Americas: A Comparative Study of Virginia and Cuba by Herbert S. Klein", The William and Mary Quarterly Vol. 25, No. 2 (Apr., 1968), pp. 307–309, in JSTOR, accessed 1 March 2015

- ↑ L. Diane Barnes (June 2008). Artisan Workers in the Upper South: Petersburg, Virginia, 1820–1865. LSU Press. pp. 128–130, 159–160. ISBN 978-0-8071-3419-1.

- ↑ "West Virginia Statehood, June 20, 1863". National Archives. August 15, 2016. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- ↑ Snell, Mark A., West Virginia and the Civil War, History Press, 2011, pgs. 23, 28-29

- ↑ Garrett, Romeo B. (October 1, 1966). "African Survivals in American Culture". The Journal of Negro History. 51 (4): 239–245. doi:10.2307/2716099. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2716099. S2CID 150275026.

- ↑ Heywood, Linda M.; Thornton, John K. (2019). "In Search of the 1619 African Arrivals: Enslavement and Middle Passage". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 127 (3): 206–208. ISSN 0042-6636. JSTOR 26743946.

- ↑ Worsham, Gibson (2003). "A Survey of Historic Architecture in Goochland County, Virginia" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. p. 82.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Booker T. Washington: nineteenth century slave diet" (PDF). National Park Service.

- 1 2 Hilliard, Sam (1969). "Hog Meat and Cornpone: Food Habits in the Ante-Bellum South". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 113 (1): 7–9. ISSN 0003-049X. JSTOR 986013.

- 1 2 Herbert C. Covey; Dwight Eisnach (2009). What the Slaves Ate: Recollections of African American Foods and Foodways from the Slave Narratives. ABC-CLIO. pp. 105–110. ISBN 978-0-313-37497-5.

- ↑ Whit, William C.; Hall, Robert L. (2007). Bower, Anne L. (ed.). African American foodways: Explorations of History and Culture. University of Illinois Press. pp. 34, 48. ISBN 978-0-252-03185-4. OCLC 76961285.

- ↑ Hilliard, Sam (1969). "Hog Meat and Cornpone: Food Habits in the Ante-Bellum South". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 113 (1): 1–13. ISSN 0003-049X. JSTOR 986013.

- 1 2 3 "Slave Clothing and Adornment in Virginia". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

- 1 2 Postma, Johannes (April 30, 1992). "The Dispersal of African Slaves in the West by Dutch Slave Traders, 1630–1803". The Atlantic Slave Trade. Duke University Press. pp. 283–300. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1220pd1.13. ISBN 978-0-8223-8237-9.

- ↑ "Journal, January 1724: Journal Book A.A." Journals of the Board of Trade and Plantations: Volume 5, January 1723 – December 1728. Ed. K H Ledward. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1928. 62–68. British History Online. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ↑ Smith, Howard W. (1978). Edward M. Riley (ed.). Benjamin Harrison and the American Revolution. Williamsburg: Virginia Independence Bicentennial Commission. OCLC 4781472.

- ↑ The WPA Guide to Virginia: The Old Dominion State. Federal Writer's Project. 1935.

- ↑ "Virginia Colony to George III of England, April 1, 1772, Petition Against Importation of Slaves from Africa". United States Library of Congress.

- ↑ Tucker, Abigail (March 2009). "Digging up the Past at a Richmond Jail". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ↑ Jack Trammell (4 March 2012). The Richmond Slave Trade: The Economic Backbone of the Old Dominion. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-1-61423-365-7.

- ↑ King, Wilma (2014). ""Prematurely Knowing of Evil Things": The Sexual Abuse of African American Girls and Young Women in Slavery and Freedom". The Journal of African American History. 99 (24): 180. doi:10.5323/jafriamerhist.99.3.0173. JSTOR 10.5323/jafriamerhist.99.3.0173. S2CID 148463530.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Slave Sales". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ↑ A. Glenn Crothers (2010). "The 1846 Retrocession of Alexandria". In Paul Finkelman; Donald R. Kennon (eds.). In the Shadow of Freedom: The Politics of Slavery in the National Capital. Ohio University Press. pp. 142–143, 167. ISBN 978-0-8214-1934-2.

- ↑ Schneider, Gregory S. (June 1, 2019). "The birthplace of American slavery debated abolishing it after Nat Turner's bloody revolt". Washington Post.

- ↑ "'Unflinching': The day John Brown was hanged for his raid on Harpers Ferry". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- ↑ Eva Sheppard Wolf (2006). Race and Liberty in the New Nation: Emancipation in Virginia from the Revolution to Nat Turner's Rebellion. LSU Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-8071-3194-7.

- ↑ Root, Erik S. (Dec 7, 2020). "The Virginia Slavery Debate of 1831–1832". Encyclopedia Virginia.

- ↑ Randolph, Thomas R. Speech of Thomas J. Randolph in the House of Delegates of Virginia, on the abolition of slavery. Richmond, VA. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ↑ Erik S. Root (2008). All Honor to Jefferson?: The Virginia Slavery Debates and the Positive Good Thesis. Lexington Books. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-7391-2218-1.

Randolph's post nati gradual emancipation plan was simple: all children born to a slave after July 4, 1840 would become the property of the state of Virginia upon reaching the age twenty one (for males) and eighteen (for females).

- ↑ Dew, Thomas (December 2008). Review of the Debate in the Virginia Legislature of 1831 and 1832. Applewood Books. pp. 7, 63–64. ISBN 978-1-4290-1390-1.

- ↑ Christopher Michael Curtis (30 April 2012). Jefferson's Freeholders and the Politics of Ownership in the Old Dominion. Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-1-107-01740-5.