| Grenfell Tower | |

|---|---|

The tower seen in 2009 before the renovation | |

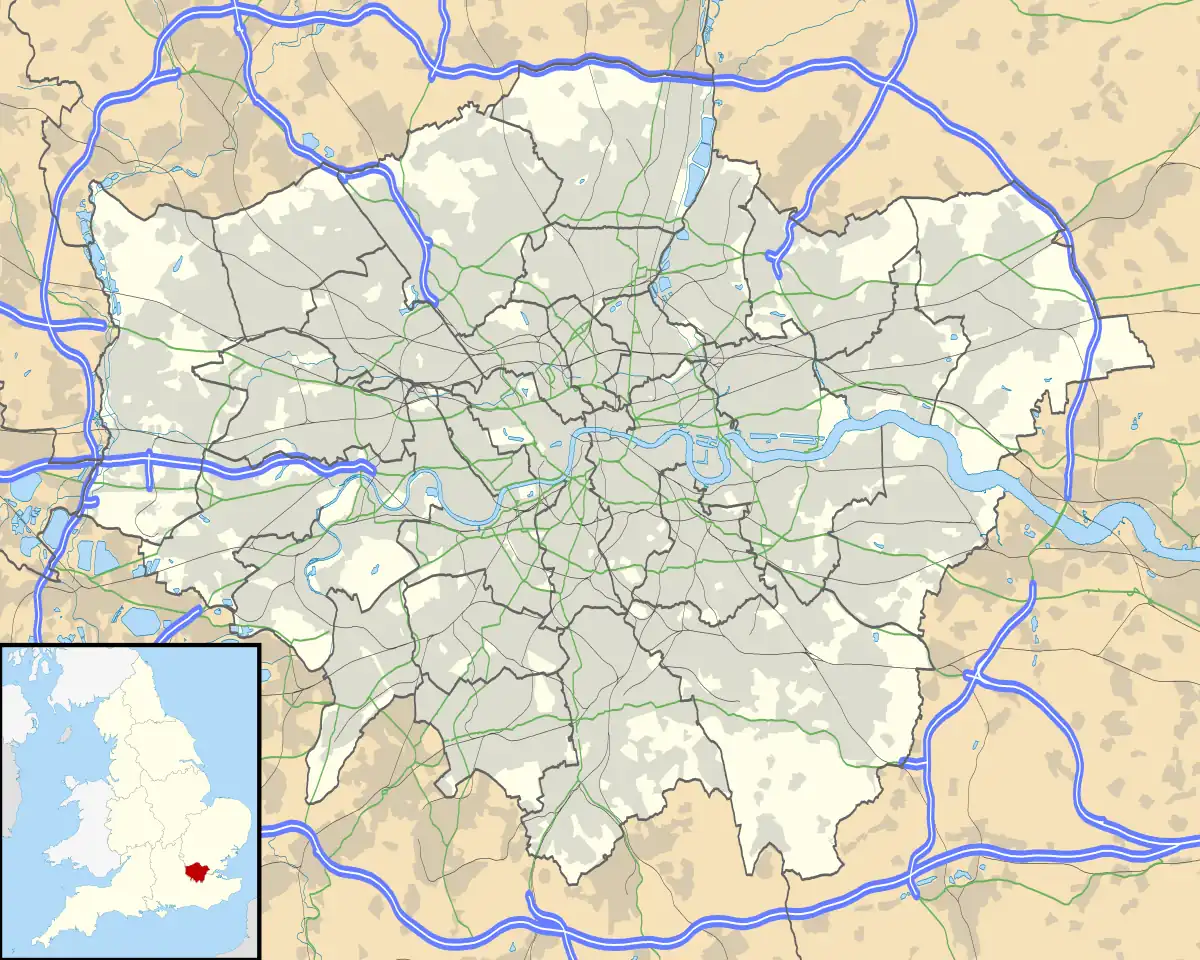

Grenfell Tower Location within Kensington and Chelsea borough  Grenfell Tower Location within Greater London | |

| Former names | Lancaster Tower |

| General information | |

| Status | Awaiting demolition |

| Location | London, W11 United Kingdom |

| Construction started | 1972 |

| Completed | 1974 |

| Renovated | 2016 |

| Destroyed | 2017 Grenfell Tower fire |

| Renovation cost | £10 million |

| Owner | Kensington and Chelsea London Borough Council |

| Landlord | Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation |

| Height | 67.3 m (220 ft 10 in) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 24 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architecture firm | Clifford Wearden and Associates |

| Main contractor | A E Symes |

| Renovating team | |

| Architect(s) | Studio E Architects |

| Renovating firm |

|

| Main contractor |

|

| Grenfell Tower, the fire, and its aftermath |

|---|

|

|

|

Grenfell Tower is a derelict 24-storey residential tower block in North Kensington in London, England. The tower was completed in 1974 as part of the first phase of the Lancaster West Estate.[1] The tower was named after Grenfell Road, which ran to the south of the building; the road itself was named after Field Marshal Lord Grenfell, a senior British Army officer.[2] Most of the tower was destroyed in a severe fire on 14 June 2017.

The building's top 20 storeys consisted of 120 flats, with six per floor – two flats with one bedroom each and four flats with two bedrooms each – with a total of 200 bedrooms. Its first four storeys were non-residential until its most recent refurbishment, from 2015 to 2016, when two of them were converted to residential use, bringing it up to 127 flats and 227 bedrooms; six of the new flats had four bedrooms each and one flat had three bedrooms. It also received new windows and new cladding with thermal insulation during this refurbishment.[3]

Prior to a fire, which began in the early hours of 14 June 2017, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and central UK government bodies "knew, or ought to have known", that their management of the tower was breaching the rights to life, and to adequate housing, of the tower's residents, according to a later enquiry by the UK Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC).[4] The fire gutted the building and killed 72 people, including a stillbirth.[5] In early 2018, it was announced that, following demolition of the tower, the site will likely become a memorial to those killed in the fire.[6]

In 2020, survivors of the fire stated that "nothing has changed" three years later and expressed feelings of being "left behind" and "disgusted" by a lack of progress in making similar buildings safe.[7]

As of December 2022, the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) has said that no firm plans exist for the tower, and that any decision will only be taken after community engagement.

Description

The 24-storey tower block was designed in 1967 in the Brutalist style of the era by Clifford Wearden and Associates, with the Kensington and Chelsea London Borough Council approving its construction in 1970, as part of phase one of the Lancaster West redevelopment project.[8][9]

The 67.3 m (221 ft) tall building contained 120 one- and two-bedroom flats (six dwellings per floor on 20 of the 24 storeys with the bottom four, the podium, being used for non-residential purposes). The floors were named ground, mezzanine, walkway and walkway+1, floor 1, floor 2 etc.[3] It housed up to 600 people.[10]

The tower was built to the Parker Morris standards. Each floor was 22 by 22 m (72 by 72 feet), giving an approximate usable area of 476 m2 (5,120 square feet). The layout of each floor was designed to be flexible as none of the partition walls were structural. The residential floors contained a two bedroom flat at each corner, in between which on the east and the west face was a one bedroomed flat. The core contained a stair column and the lift and service shafts.[11] One-bedroom flats were 51.4 m2 (553 square feet) in area and two-bedroom flats were 75.5 m2 (813 square feet).[10]

The building was innovative, as most LCC tower blocks used traditional brick work for infill whereas here precast insulated concrete blocks were used, giving the walls an unusual texture. The ten exterior concrete columns were also unusual.[12] In addition, other tower blocks of this era had four flats per storey, rather than six.[11]

The original lead architect for the building, Nigel Whitbread, said in 2016 in an interview with Constantine Gras, which was later partially repeated in The Guardian,[13] that the tower had been designed with attention to strength, unlike the collapsed Ronan Point tower of the same period, "and from what I can see could last another 100 years." He described it as a "very simple and straightforward concept. You have a central core containing the lift, staircase and the vertical risers for the services and then you have external perimeter columns. The services are connected to the central boiler and pump which powered the whole development and this is located in the basement of the tower block. This basement is approximately four metres deep [14'] and in addition has two metres [7'] of concrete at its base. This foundation holds up the tower block and in situ concrete columns and slabs and pre-cast beams all tie the building together".[11]

History

Construction, by contractors A E Symes, of Leyton, London, commenced in 1972, with the building being completed in 1974. Before construction, the plans at basement level were changed from the original brief to accommodate the need for extra car-parking. In the early 1990s, access to the building was restricted through the use of key fobs, and lift access to the first four storeys was discontinued. The building was renovated in 2015–16.[14]

When the building opened in 1974, it was nicknamed the 'Moroccan Tower' because many tenants came from the local Moroccan immigrant community.[15] In recent years, some residents had become leaseholders, mostly under the Right to Buy scheme; 14 flats in the tower, and three in Grenfell Walk, were leaseholder owned at the time of the 2017 fire.[16]

Renovation

The renovation was part of a project to utilise the area around Lancaster Green.[17] The new Kensington Leisure Centre had already been built to the east of the green, and the all-weather football pitches to the north of the tower were destined to become Kensington Academy. The renovation aimed to replace the substandard heating system, replace the windows, increase the thermal efficiency of the tower and improve appearance of the tower in the style of the academy.[14]

It aimed to reconfigure the podium levels in order to use the space more efficiently. The nursery would move from 244 m2 (2,630 sq ft) on the mezzanine floor to 206 m2 (2,220 sq ft) on the ground floor with immediate access to outside play space. The mezzanine floor would be continued across the full width of the building making space for three four-bedroom, 101.5 m2 (1,093 sq ft) six-person flats. The Dale Youth boxing club gained almost 100 m2 (1,100 sq ft) extra space by moving from the ground floor to the walkway level (190 m2 (2,000 sq ft) to 287 m2 (3,090 sq ft)). Walkway + 1 level would be converted from offices, to four new four-bedroom, six-person flats.[14]

Plans by Studio E Architects for renovation of the tower were publicised in 2012. The £8.7 million refurbishment, undertaken by Rydon Ltd, of Forest Row, East Sussex in conjunction with Artelia for contract administration and Max Fordham as specialist mechanical and electrical consultants, was completed in 2016. As part of the project, in 2015–2016, the concrete structure received new windows and new aluminium composite rainscreen cladding, in part to improve the appearance of the building.[14]

Two types were used: Arconic's Reynobond PE, which consists of two coil-coated aluminium sheets that are fusion bonded to both sides of a polyethylene core; and Reynolux aluminium sheets. Beneath these, and fixed to the outside of the walls of the flats, was Celotex RS5000 polyisocyanurate (PIR) thermal insulation. The work was carried out by Harley Facades of Crowborough, East Sussex, at a cost of £2.6 million.[18]

Fire

.jpg.webp)

A fire broke out on 14 June 2017, which killed 72 of Grenfell's residents.[19] Emergency services received the first report of the fire at 00:54 local time. It burned for around 24 hours.[20] Initially, hundreds of firefighters and 45 fire engines were involved in efforts to control the fire, with many firefighters continuing to attempt to control pockets of fire on the higher floors after most of the rest of the building had been gutted. Residents of surrounding buildings were evacuated due to concerns that the tower could collapse, though the building was later determined to be structurally sound.[21]

Fate

After the fire, the exterior was covered in a protective wrap to assist the outstanding forensic investigations.[22] The Government, the Kensington and Chelsea Council, and the Grenfell United survivors' group, have agreed that at the conclusion of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry the demolished tower will be replaced by a memorial to the victims.[23] The government has voiced its intention to allow the survivors to "...guide the way future decisions are made" about the tower site and memorial. By May 2021, demolition of the tower was not expected to begin until June 2022 at the earliest.[24] However, as of December 2022, the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) has said that no firm plans exist for the tower, and that any decision will only be taken after further community engagement.[25] The Grenfell Next of Kin group has proposed turning the tower into a green wall vertical garden as a memorial to the victims.[26]

Architect

Nigel Whitbread was the lead architect for the Grenfell Tower.[27] In an interview with Constantine Gras, quoted in The Guardian, he said that "he was born in Kenton, his parents had a grocer's shop on St Helen's Gardens, North Kensington. He was educated at Sloane Grammar school and then got a position with the architects Douglas Stephen and Partners, who, though small, were applying the principles of Le Corbusier and the modernists."[27] He worked alongside Kenneth Frampton who was the Technical Editor of the journal Architectural Design; and Elia Zenghelis and Bob Maxwell. He moved to work for Clifford Wearden after the basic plan for Lancaster West Estate had been established. He later worked for 30 years until his retirement at Aukett Associates.[28] Around 2016, he became involved with the local residents association drawing up the St Quintin and Woodlands Neighbourhood Plan.[29][30]

Grenfell Action Group

A residents' organisation, Grenfell Action Group (GAG), published a blog in which it highlighted major safety problems. In the four years preceding the fire, they published 10 warnings criticising fire safety and maintenance practices at Grenfell Tower.[31]

- In 2013, the group published a 2012 fire risk assessment done by a tenant management organisation (TMO) Health and Safety Officer which recorded safety concerns. Firefighting equipment at the tower had not been checked for up to four years; on-site fire extinguishers had expired, and some had the word "condemned" written on them because they were so old. GAG documented its attempts to contact Kensington and Chelsea TMO (KCTMO) management; they also alerted the council Cabinet Member for Housing and Property but said they never received a reply from him or his deputy.[32]

- In July 2013, the council threatened the group's blogger with legal action, accusing them of "defamatory behaviour" and "harassment".[33]

- In November 2016, GAG warned that people might be trapped in the building if a fire broke out, pointing out that the building had only one entrance and exit, and corridors that were often filled with rubbish, such as old mattresses. GAG published an online article attacking KCTMO as an "evil, unprincipled, mini-mafia" and accusing the council of ignoring health and safety laws. In the blog post, they warned that "only a catastrophic event" would "expose the ineptitude and incompetence of [KCTMO]" and "bring an end to the dangerous living conditions and neglect of health and safety legislation" at the building, adding, "[We] predict that it won't be long before the words of this blog come back to haunt the KCTMO management and we will do everything in our power to ensure that those in authority know how long and how appallingly our landlord has ignored their responsibility to ensure the health and safety of their tenants and leaseholders. They can't say that they haven't been warned!"[10][34]

References

- ↑ The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. "Grenfell Tower". rbkc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ↑ "Who was Grenfell Tower named after and what do we know about the man?". Metro. 14 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- 1 2 Grenfell Tower regeneration Project Archived 17 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Booth, Robert (13 March 2019). "Grenfell residents' rights were breached – equalities watchdog". The Guardian, Theguardian.com. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ↑ "UPDATE: Number of victims of the Grenfell Tower fire formally identified is 70". Metropolitan Police. 16 November 2017. Archived from the original on 19 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ↑ "Grenfell Tower site to be turned into memorial". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ↑ "Grenfell Tower: Survivors say 'nothing has changed'". BBC News. 14 June 2020.

- ↑ "Category: Lancaster West Estate". Constantine Gras. self. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ↑ Boughton, John (26 July 2017). "A perfect storm of disadvantage: the history of Grenfell Tower – The i newspaper online iNews". iNews, inews.co.uk. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Grenfell Tower floorplan shows how 120 flats were packed into highrise". The Telegraph. 14 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 Whitbread, Nigel. "Lancaster West Estate: An Ideal For Living?". Constantine Gras. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ↑ Marsden, Harriet (25 June 2017). "Grenfell Tower's unusual design 'contributed to speed of fire'". The Independent.

- ↑ Siddique, Nicola Slawson (now) Haroon; Weaver, Matthew; Watt, Holly (17 June 2017). "Protesters march as anger mounts over Grenfell Tower response – as it happened". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Studio E (October 2012). "Grenfell Tower Regeneration Project-Design and Access Statement" (PDF). Rbkc.gov.uk. p. 24. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ↑ Graham-Harrison, Emma (8 July 2017). "Grenfell fire: 'The community is close knit – they need to stay here to recover'". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ Turner, Camilla (10 July 2017). "Victims of Grenfell Tower inferno who bought their homes say authorities have abandoned them". The Telegraph. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ "History – From Core Strategy to Kensington Academy". Grenfell Action Group. 24 June 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ↑ Davies, Rob (26 June 2017). "Grenfell Tower: cladding material linked to fire pulled from sale worldwide". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ Davies, Caroline; Slawson, Nicola (18 June 2017). "Grenfell Tower fire: Police say at least 58 missing as No 10 says each family to get £5,500 – live updates". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ↑ Bentham, Martin (15 June 2017). "London fire: Grenfell Tower death toll reaches 17 as fire chief says 'no more survivors'". Evening Standard. London. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ↑ "Sky News – Live". Sky News. Sky UK. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Work to start on covering Grenfell Tower". BBC. 27 July 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ↑ Pasha-Robinson, Lucy (1 March 2018). "Grenfell Tower survivors told they can transform charred block into memorial of their choice". The Independent. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ Duffy, Nick (11 May 2021). "Government to consider 'if and when' to pull down Grenfell Tower for safety". i. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ↑ "Grenfell Tower site update: summary of community online meeting" (PDF). Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. 6 December 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ↑ Brown, David. "Grenfell Tower father wants to turn ruins into a high-rise garden". The Times. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- 1 2 Siddique, Nicola Slawson (now) Haroon; Weaver, Matthew; Makin, Bonnie; Watt, Holly (17 June 2017). "Protesters march as anger mounts over Grenfell Tower response – as it happened". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ "Nigel James Whitbread, former director at Aukett Swanke Limited, London". Checkdirector.co.uk. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ "Committee". stqw.org. St Quintin and Woodlands Neighbourhood Forum. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ Gras, Constantine (3 June 2016). "Lancaster West Estate - An Ideal For Living?". Constantine Gras. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ↑ "Grenfell Tower Fire". 14 June 2017. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ↑ "Fire Department Risk Assessment". What Go. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ Fifield, Nicola (17 June 2017). "Grenfell Tower missing pair were sent legal threats after fire safety warning". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

Two women feared dead in Grenfell Tower tragedy were threatened with legal action - after raising alarm about fire safety. Mariem Elgwahry and Nadia Choucair were branded 'troublemakers' because they campaigned to make their homes safer

- ↑ "KCTMO – Playing with fire!". 20 November 2016. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017.