Henrik Wergeland | |

|---|---|

Henrik Wergeland | |

| Born | Henrik Arnold Thaulow Wergeland 17 June 1808 Kristiansand, Denmark-Norway |

| Died | 12 July 1845 (aged 37) Christiania (now Oslo), Norway |

| Pen name | Siful Sifadda (farces) |

| Occupation | Poet, playwright and non-fiction writer |

| Period | 1829–1845 |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

Henrik Arnold Thaulow Wergeland (17 June 1808 – 12 July 1845) was a Norwegian writer, most celebrated for his poetry but also a prolific playwright, polemicist, historian, and linguist. He is often described as a leading pioneer in the development of a distinctly Norwegian literary heritage and of modern Norwegian culture.[1]

Though Wergeland only lived to be 37, his range of pursuits covered literature, theology, history, contemporary politics, social issues, and science. His views were controversial in his time, and his literary style was variously denounced as subversive.[2]

Early life

He was the oldest son of Nicolai Wergeland (1780–1848), who had been a member of the constituent assembly at Eidsvoll in 1814. The father was himself pastor of Eidsvold and the poet was thus brought up in the very holy of holies of Norwegian patriotism.[3] Wergeland's younger sister was Camilla Collett and younger brother major general Joseph Frantz Oscar Wergeland.

Henrik Wergeland entered The Royal Frederick University in 1825 to study for the church and graduated in 1829. That year, he became a symbol of the fight for celebration of the constitution at 17 May, which was later to become the Norwegian National Day. He became a public hero after the infamous "battle of the Square" in Christiania, which came to pass because any celebration of the national day was forbidden by royal decree.[4] Wergeland was, of course, present and became renowned for standing up against the local governors. Later, he became the first to give a public address on behalf of the day and thus he was given credit as the one who "initiated the day". His grave and statues are decorated by students and school children every year. Notably, the Jewish community of Oslo pays their respects at his grave on 17 May, in appreciation of his successful efforts to allow Jews into Norway.

Early poetry

In 1829 he published a volume of lyrical and patriotic poems, Digte, første Ring (poems, first circle), which attracted the liveliest attention to his name. In this book we find his ideal love, the heavenly Stella, which can be described as a Wergeland equivalent to Beatrice in Dante's poem Divina Commedia. Stella is in fact based on four girls, whom Wergeland fell in love with (two of whom he wooed), and never got really close to. The character of Stella also inspired him to endeavour on the great epic Skabelsen, Mennesket og Messias (Creation, Man and the Messiah). It was remodeled in 1845 as Mennesket (Man). In these works, Wergeland shows the history of Man and God's plan for humanity. The works are clearly platonic-romantic, and is also based on ideals from the enlightenment and the French Revolution. Thus, he criticizes abuse of power, and notably evil priests and their manipulation of people's minds. In the end, his credo goes like this:

- Heaven shall no more be split

- after the quadrants of altars,

- the earth no more be sundered and plundered

- by tyrant's sceptres.

- Bloodstained crowns, executioner's steel

- torches of thralldom and pyres of sacrifice

- no more shall gleam over earth.

- Through the gloom of priests, through the thunder of kings,

- the dawn of freedom,

- bright day of truth

- shines over the sky, now the roof of a temple,

- and descends on earth,

- who now turns into an altar

- for brotherly love.

- The spirits of the earth now glow

- in freshened hearts.

- Freedom is the heart of the spirit, Truth the spirit's desire.

- earthly spirits all

- to the soil will fall

- to the eternal call:

- Each in own brow wears his heavenly throne.

- Each in own heart wears his altar and sacrificial vessel.

- Lords are all on earth, priests are all for God.

At the age of twenty-one he became a power in literature, and his enthusiastic preaching of the doctrines of the French July Revolution of 1830 made him a force in politics also. Meanwhile, he was tireless in his efforts to advance the national cause. He established popular libraries, and tried to alleviate the widespread poverty of the Norwegian peasantry. He preached the simple life, denounced foreign luxuries, and set an example by wearing Norwegian homespun clothes.[3] He strove for enlightenment and greater understanding of the constitutional rights his people had been given. Thus, he became increasingly popular among common people.

In his historic essay Hvi skrider Menneskeheden saa langsomt frem? (Why does humanity progress so slowly), Wergeland expresses his conviction that God will guide humanity to progress and brighter days.[5]

Personal and political struggle

Critics, especially Johan Sebastian Welhaven, claimed his earliest efforts in literature were wild and formless. He was full of imagination, but without taste or knowledge.[3] Therefore, from 1830 to 1835 Wergeland was subjected to severe attacks from Welhaven and others. Welhaven, being a classicist, could not tolerate Wergeland's explosive way of writing, and published an essay about Wergeland's style. As an answer to these attacks, Wergeland published several poetical farces under the pseudonym of "Siful Sifadda". Welhaven showed no understanding of Wergeland's poetical style, or even of his personality. On one hand, the quarrel was personal, on the other, cultural and political. What had started as a mock-quarrel in the Norwegian Students' Community soon blew out of proportion and became a long lasting newspaper dispute for nearly two years. Welhaven's criticism, and the slander produced by his friends, created a lasting prejudice against Wergeland and his early productions.

Recently, his early poetry has been reassessed and more favorably recognized. Wergeland's poetry can in fact be regarded as strangely modernistic yet containing elements of traditional Norwegian Eddic verse. In the pattern of the classical 6-11th century Norse poets, his intellectual forefathers, his writing is evocative and intentionally veiled - featuring elaborate kennings that require extensive context to be deciphered. From early on, he wrote poems in free style, without rhymes or metre. His use of metaphors are vivid, and complex, and many of his poems quite long. He challenges the reader to contemplate his poems over and over, but so do his contemporaries Byron and Shelley, or even Shakespeare. The free form and multiple interpretations especially offended Welhaven, who held an aesthetical view of poetry as appropriately concentrated on one topic at a time.

Wergeland, who until this point had written in Danish, supported the thought of a separate and independent language for Norway. Thus, he preceded Ivar Aasen by 15 years. Later, the Norwegian historian Halvdan Koht would say that "there is not one political cause in Norway which has not been seen and anticipated by Henrik Wergeland".

Personality

Wergeland had a hot temper and fought willingly for social justice. At the time, poverty was normal in the rural areas, and serfdom was common. He was generally suspicious of lawyers because of their attitude towards farmers, especially poor ones, and often fought lawyers and jurists in the courts, who could legally take hold of small homesteads. Wergeland made great enemies for this, and in one case, the judicial problem lasted for years and nearly left him bankrupt. The quarrel had started at Gardermoen, at the time a drill field for a section of the Norwegian army. In his plays, his nemesis, the procurator Jens Obel Praëm, would be cast as the devil himself.

Wergeland was tall, reckoned by the average Norwegian height at the time. He stood a head taller than most of his contemporaries (about 1m and 80 cm). Often, he could be seen gazing upwards, especially when he rode his horse through town. The horse, Veslebrunen (little brown), is reckoned to be a small Norwegian breed (but not a pony). Thus, when Wergeland rode his horse, his feet dragged after him.

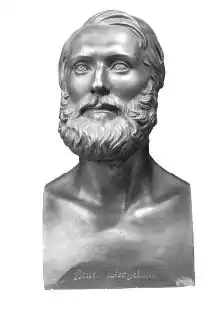

by Hans Hansen. 1845

Entry in a playwrights' competition

In the autumn of 1837, Wergeland took part in a playwright's competition for the theater in Christiania. He came second, just behind Andreas Munch. Wergeland had written a musical play, Campbellerne (The Campbells). This play was based on tunes and poems by Robert Burns, and the plot commented on both Company rule in India and serfdom in Scotland. At the same time, he expressed several critical sentiments towards prevailing social conditions in Norway, including poverty and avaricious lawyers. The play was an immediate crowd-pleaser, and was later considered by many to be his greatest theatrical success.

But the riots began on the second day of performance, 28 January 1838. To this performance, 26 distinguished high-ranking gentlemen from the university, court and administration mustered to take Wergeland once and for all. They bought themselves the best seats in the audience, and armed with small toy-trumpets and pipes, they began to interrupt the performance from the very beginning. The tumult rose, and the chief of the Christiania police could do nothing more than shout for order while jumping in his seat. Later, it has been said that the high-ranking gentlemen acted like schoolboys, and one of them, an attorney in the high court, broke into the lounge of Nicolai Wergeland, bellowing straight in his ear. The poet's father was astonished by this behaviour. The assailant is said to have been the later Norwegian prime minister Frederik Stang. One of the actors finally calmed the audience, and the play commenced. Later, after the play, the ladies in the first and second row acted on behalf of Wergeland, throwing rotten tomatoes at the offenders, and then fights erupted, inside and outside the theater building, and in the streets nearby. Allegedly, some of them tried to escape, and were dragged back for another round of beating. The offenders were shamed for weeks, and dared not show themselves for a while. The story of this battle, called "the battle of the Campbells" (Cambellerslaget), was witnessed and recorded by a member of the Norwegian Parliament.

One might conclude that the followers of Wergeland won the day, but the men in position might have taken some revenge by slandering Wergeland's reputation after his death.

In February, a performance was held "for the benefit of Mr Wergeland", and this gave him enough money to purchase a small abode outside town, in Grønlia under the hill of Ekeberg.

Marriage

From Grønlia, Wergeland had to row across the fjord to a small inn at the Christiania quay. Here, he met Amalie Sofie Bekkevold, then 19 years of age, daughter of the proprietor. Wergeland quickly fell in love, and proposed the same autumn. They got married on 27 April 1839 in the church of Eidsvoll, with Wergeland's father as priest.

Although Amalie was working class, she was also charming, witty and intelligent, and soon won the hearts of her husband's family. Camilla Collett became her trusted friend throughout their lives. The marriage produced no children, but the couple adopted Olaf, an illegitimate son Wergeland had fathered in 1835, and Wergeland secured an education for the boy. Olaf Knutsen, as he was called, would later become the founder of the Norwegian School-gardening, and a prominent teacher.

Amalie became the inspiration for a new book of love poems; this book was filled with images of flowers, whereas his earlier love poems had been filled with images of stars. After Wergeland's death, she married the priest, Nils Andreas Biørn, who officiated at his funeral and was an old college friend of Wergeland.[6] She had eight children by him. But at her death many years later, her eulogy was as follows: The widow of Wergeland has died at last, and she has inspired poems like no-one else in Norwegian literature.

Employment

Wergeland had tried to get employment as a chaplain or priest for many years up to this point. He was always turned down, mostly because the employers found his way of living "irresponsible" and "unpredictable". His legal strife with Praëm was also a hindrance. The department stated that he could not get a parish while this case was still unresolved. His last attempt vanished "on a rose-red cloud" during the winter of 1839, due to an incident in a tavern when he drew blood by striking his head with a pewter plate after his advances on a nearby patron were rejected.

Meanwhile, Wergeland worked as a librarian at the University Library for a small wage, from January 1836. In the period 1835–1837 he edited a radical magazine entitled Statsborgeren.[7] In late autumn 1838, King Carl Johan offered him a small "royal pension" that nearly doubled his salary. Wergeland accepted this as a payment for his work as a "public teacher". This pension gave Wergeland enough income to marry and settle down. His marriage the same spring made him calmer, and he applied again, this time for the new job as head of the national archive. The application is dated January 1840. Eventually, he obtained it, and was employed from 4 January 1841 until he had to retire in the autumn of 1844.

On 17 April 1841, he and Amalie moved to his new home, Grotten, situated near the new Norwegian royal palace, and here he lived the next few years.

Personal struggles

After his employment, Wergeland became suspected by his earlier comrades in the republican movement, of betraying his cause. He, as left-wing, should not have taken anything from the King. Wergeland had an ambiguous view of Carl Johan. In one perspective, he was a symbol of the French Revolution, a reminder of values Wergeland admired. On the other hand, he was the Swedish king who had hindered the national independence. The radicals called Wergeland a renegade, and he defended himself in many ways. But it was apparent that he himself felt lonely and betrayed. On one occasion, he was present at a students' party, and tried to propose a toast for the old professors, and was rudely interrupted. After a couple of attempts, he despaired and broke a bottle against his forehead. Only one single person, a physician, later recalled that Wergeland wept that night. Later that evening, the students prepared a procession in honour of the university, and they all left Wergeland behind. Only one student offered him his arm, and this was enough to get Wergeland back in the mood. The student was Johan Sverdrup, later the father of Norwegian parliamentarism. Thus, the two symbols of Norwegian left-wing movement, a generation apart, walked together.

But Wergeland was barred from writing in some of the bigger newspapers, and was therefore not allowed to defend himself. The paper Morgenbladet would not print his answers, not even his poetical responses. One of his best known poems was written at this time, a response to the paper's statement that Wergeland was "irritable and in a bad mood". Wergeland responded in free metre:

I in a bad mood, Morgenblad? I, who need nothing more than a glimpse of sun to burst out in loud laughter, from a joy I cannot explain?

The poem was printed in another newspaper, and Morgenbladet printed the poem with an apology to Wergeland in the spring of 1846.

In January 1844 the court decided on a compromise in the Praëm case. Wergeland had to bail himself out, and he felt humiliated. The sum was set at 800 speciedaler, more than he could afford. He had to sell his house, and Grotten was purchased the following winter by a good friend of his, who understood his plight.

The psychological pressure may have contributed to his illness.

Period of illness prior to death

In the spring of 1844, he caught pneumonia and had to stay at home for a fortnight. While recovering, he insisted on taking part in the national celebrations that year, and his sister Camilla met him, "pale as death, but in the spirit of 17 May" on his way to the revels. Soon after, his illness returned, and now he had symptoms of tuberculosis as well. He had to stay inside, and the illness turned out to be terminal. There have been many theories about the nature of his sickness. There are some who claim he developed lung cancer after a lifetime of smoking. At the time, the dangers of smoking were unknown to most people. This last year, he wrote rapidly from his sickbed, letters, poems, political statements and plays.

Due to his economic situation, Wergeland moved to a smaller house, Hjerterum, in April 1845. Grotten was then sold. But his new home was not yet finished, and he had to spend ten days at the national hospital Rikshospitalet. Here, he wrote some of his best known sickbed poems. He wrote almost to the end. The last written poem is dated 9 July, three days before his death.

Death

Henrik Wergeland died in his home early morning 12 July 1845. His funeral was held 17 July, and was attended by thousands, many of whom had traveled from the districts around Christiania. The priest had expected some hundreds, but had to correct himself. The congregation was ten times that number. His coffin was carried by the Norwegian students, while the appointed wagon went in front of them empty. Allegedly, the students insisted on carrying the coffin themselves. Wergeland's grave was left open during the afternoon, and all day, people revered him by spreading flowers on his coffin, until evening came. His father wrote his thanks for this in Morgenbladet three days later (20 July), stating that his son had gotten his honour at last:

Now I see how you all loved him, how you revered him... God reward and bless you all! The brother you held in such esteem had a risky beginning, was misunderstood a long time and suffered long, but had a beautiful ending. His life was not strewn with roses, but his death and grave the more - (Nicolai Wergeland).

Change of site at cemetery

Wergeland was in fact laid in a humble section of the churchyard, and soon his friends began to write in the newspapers, claiming a better site for him. He was eventually moved to his present grave in 1848. At this time, debate arose about a proper monument for his grave. The monument on his grave was provided by Swedish Jews, and officially "opened" 17 June 1849, after six months of delay.

Legacy

His statue stands between the Royal Palace and Storting by Oslo's main street, his back turned to Nationalteateret. On Norwegian Constitution Day, it receives an annual wreath of flowers from students at the University of Oslo. This monument was raised on 17 May 1881, and the oration at this occasion was given by Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson.

During the Second World War, the Nazi occupiers forbade any celebration of Wergeland.

Works

The collected writings of Henrik Wergeland (Samlede Skrifter : trykt og utrykt) were published in 23 volumes in 1918–1940, edited by Herman Jæger and Didrik Arup Seip. An earlier compilation also titled Samlede Skrifter ("Collected Works", 9 vols., Christiania, 1852–1857) was edited by H. Lassen, the author of Henrik Wergeland og hans Samtid (1866), and the editor of his Breve ("Letters", 1867).[3]

Wergeland's Jan van Huysums Blomsterstykke (Flower-piece by Jan van Huysum, 1840), Svalen (The Swallow, also translated to English, 1841), Jøden (The Jew 1842), Jødinden (The Jewess 1844) and Den Engelske Lods (The English Pilot 1844), form a series of narrative poems in short lyrical metres which remain the most interesting and important of their kind in Norwegian literature. He was less successful in other branches of letters; in the drama neither his Campbellerne (The Campbells 1839), Venetianerne (The Venetians 1843), nor Søkadetterne (The Sea Cadets 1837), achieved any lasting success; while his elaborate contribution to political history, Norges Constitutions Historie (The History of the Norwegian Constitution) 1841–1843, is still regarded as an important source. The poems of his later years include many lyrics of great beauty, which are among the permanent treasures of Norwegian poetry.[3]

Wergeland became a symbol for the Norwegian Left-wing movement, and was embraced by many later Norwegian poets, right up until today. Thus, a great number of later poets owe him allegiance in one way or another. As the Norwegian poet Ingeborg Refling Hagen said, "When in our footprints something sprouts,/ it's a new growth of Wergeland's thoughts." She, among others, initiated an annual celebration on his birthday. She started the traditional "flower-parade", and celebrated his memory with recitation and song, and often performing his plays.

Wergeland's most prominent poetical symbols are the flower and the star, symbolizing heavenly and earthly love, nature and beauty.

His lyrics have been translated into English by Illit Gröndal,[8] G. M. Gathorne-Hardy, Jethro Bithell,[9] Axel Gerhard Dehly[10] and Anne Born.[11]

Family

His father was the son of a bellringer from Sogn, and Wergeland's paternal ancestry is mostly farmers from Hordaland, Sogn and Sunnmøre. On his mother's side, he descended from both Danes and Scots. His great-grandfather, Andrew Chrystie (1697–1760), was born in Dunbar, and belonged to the Scottish Clan Christie. This Andrew migrated in 1717 to Brevik in Norway, moved on to Moss and was married a second time to a Scottish woman, Marjorie Lawrie (1712–1784). Their daughter Jacobine Chrystie (1746–1818) was married to the town clerk of Kristiansand Henrik Arnold Thaulow (1722–1799), father of Wergeland's mother Alette Thaulow (1780–1843). Wergeland got his first name from the elder Henrik Arnold.[12]

His ancestors with the name Wergeland lived at Verkland, a farm in Ytre Sogn[13] "at the top of the valley leading from Yndesdalvatnet, North of the county line towards Hordaland".[14] (Wergeland is a Danish transliteration of Verkland.[13])

Further reading

- Benterud, Aagot (1943). Henrik Wergelands religiøse utvikling: en litteraturhistorisk studie (in Norwegian). Oslo: Dreyers forlag. OCLC 729144143.

References

- ↑ Family of Joseph Frantz Oscar Wergeland

- ↑ Henrik Wergeland – utdypning (Store norske leksikon)

- 1 2 3 4 5 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Wergeland, Henrik Arnold". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 522.

- ↑ Wergeland hailed on 200th birthday Archived 20 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Aftenposten, 17 June 2008

- ↑ Norsk biografisk leksikon. Henrik Wergeland

- ↑ no:Amalie Sofie Bekkevold

- ↑ Øyvind Andresen (5 January 2021). "Fædrelandsvennens første redaktør". Argument. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ↑ Henrik Wergeland, the Norwegian poet by Illit Gröndal, (Oxford, B.H. Blackwell, 1919).

- ↑ Poems by Henrik Wergeland translated by G. M. Gathorne-Hardy, Jethro Bithell and I. Grøndahl, (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1929)

- ↑ Eagle wings: poetry by Bjørnson, Ibsen and Wergeland translated by Axel Gerhard Dehly, (Auburndale, Massachusetts: Maydell Publications, 1943)

- ↑ The army of truth: selected poems by Henrik Wergeland edited by Ragnhild Galtung, (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003)

- ↑ Nicolai Wergeland – utdypning(Store norske leksikon)

- 1 2 Sylfest Lomheim (5 August 2015). "Dølar på Dalen". Klassekampen. p. 10.

- ↑ Wergeland-støtta på Verkland

External links

- Henrik Wergeland statue in Fargo, North Dakota

- Wergeland statue by Gustav Vigeland

- Works by Henrik Wergeland at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Henrik Wergeland at Internet Archive

Norwegian

- Henrik Wergeland at Norske Dikt

- Henrik Wergeland at the Internet Archive

- Henrik Wergeland at Norwegian Wikisource

- Henrik Wergeland at the Lied and Art Song Archive

- Digitized books by Wergeland in the National Library of Norway

- Electronic text: "Samlede Skrifter (23 vols., 1918–1940)" (in Norwegian). Oslo: Dokumentasjonsprosjektet. 13 August 1998. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- Electronic text and scanned images: "Samlede Skrifter (23 vols., 1918–1940)" (in Norwegian). NBdigital, Norway's National Library. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

English

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Henrik Wergeland in the Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Henrik Wergeland, the Norwegian poet 1919

Translations

Streaming audio

Poem

- Juleaften: Norwegian lyrics

- Juleaften: English translation

- Juleaften: on YouTube Torstein Blixfjord film