| History of Bengal |

|---|

|

| History of South Asia |

|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png.webp) |

The Greater Sylhet region predominantly included the Sylhet Division in Bangladesh, and Karimganj district in Assam, India. The history of the Sylhet region begins with the existence of expanded commercial centres in the area that is now Sylhet City. Historically known as Srihatta and Shilhatta, it was ruled by the Buddhist and Hindu kingdoms of Harikela and Kamarupa before passing to the control of the Sena and Deva dynasties in the early medieval period.[1][2] After the fall of these two Hindu principalities, the region became home to many more independent petty kingdoms such as Jaintia, Gour, Laur, and later Taraf, Pratapgarh, Jagannathpur, Chandrapur and Ita. After the Conquest of Sylhet in the 14th century, the region was absorbed into Shamsuddin Firoz Shah's independent principality based in Lakhnauti, Western Bengal. It was then successively ruled by the Muslim sultanates of Delhi and the Bengal Sultanate before collapsing into Muslim petty kingdoms, mostly ruled by Afghan chieftains, after the fall of the Karrani dynasty in 1576. Described as Bengal's Wild East, the Mughals struggled in defeating the chieftains of Sylhet.[3] After the defeat of Khwaja Usman, their most formidable opponent, the area finally came under Mughal rule in 1612.[4] Sylhet emerged as the Mughals' most significant imperial outpost in the east and its importance remained as such throughout the seventeenth century.[5] After the Mughals, the British Empire ruled the region for over 180 years until the independence of Pakistan and India. There was a complete list of the different amils who governed Sylhet which was recorded in the office of the Qanungoh (revenue officers) of Sylhet. However, most complete copies have been lost or destroyed. Dates from letters and seal traces show evidence that the amils were constantly changed.[6] In 1947, when a referendum was held, Sylhet decided to join the Pakistani province of East Bengal. However, when the Radcliffe Line was drawn up, Karimganj district of Barak Valley was given to India by the commission after being pleaded by Abdul Matlib Mazumdar's delegation. Throughout the History of Sylhet, raids and invasions were also common from neighbouring kingdoms as well as tribes such as the Khasis and Kukis.

Ancient

According to historians, Sylhet was an expanded commercial centre inhabited by Brahmans under the realm of the Harikela and Kamarupa kingdoms of ancient Bengal and Assam. Buddhism was prevalent in the first millennium.

The Hindu epic known as the Mahabharata mentions the marriage of Duryodhana of the Kauravas into a family in Habiganj, Sylhet. The Purana also mentions the hero Arjuna travelling to the Jaintia to regain his horse held captive by a princess.[7] The region is also home to two of the fifty-one body parts of Sati, a form of Durga, that fell on Earth according to accepted legends. Shri Shail and Jayanti are where the neck and left palm of Sati fell and are Shakti Peethas.

The Gour Kingdom, established in the 7th century, took part in many battles with its neighbouring states. Eventually it would split into two - Gour (Sylhet) and Brahmachal (South Sylhet/modern-day Moulvibazar). The region was also home to many petty kingdoms such as Laur and Jagannathpur and part of larger kingdoms such as the Jaintia and Twipra Kingdoms. In 640, the Raja of Tripura Dharma Fa planned a ceremony and invited five Brahmans from Etawah, Mithila and Kannauj. To compensate for their long journey, the Raja granted them land in a place which came to be known as Panchakhanda (meaning five parts) in Western Sylhet. Towards the end of the millennium, the Candras ruled over Bengal.

A 930 AD copper-plate of Srichandra, of the Chandra dynasty of East Bengal, was found in Tengubazar Mandir, Paschimbhag, Rajnagar detailing his successful campaign against the Kingdom of Kamarupa. In the early medieval period, the area was dominated by Hindu principalities, which were under the nominal suzerainty of the Senas and Devas.[1][8] The history of the dynasties in the region is documented by their copper-plate charters.[9]

Evidence from inscriptions also suggest there was an ancient university in Panchgaon, Rajnagar.[10] A copper-plate inscription of Raja Marundanath in Kalapur, Srimangal was discovered dating back to the 11th century. In 1195, Nidhipati Shastri, a Brahman from Panchakhanda who was descended from Ananda Shastri of Mithila, was given land in Ita (Rajnagar) by the Raja of Tripura. Ita was feudal to the Kingdom of Tripura and part of its Manukul Pradesh. Nidhipati became the founder of the Ita dynasty which would later gain a Raja status and based himself in Bhumiura-Ettolatoli. He established many dighis (ponds) and khamar (fields) which still exist today such as Shoptopar Dighi and Nidhipatir Khamar. He was succeeded over the feudal rule of Ita by his son, Bhudhar and then his grandson, Kandarpadi.[11]

Keshab Misra, a Brahman from Kannauj, migrated to Laur where he established a Hindu kingdom.[12] After the death of Raja Upananda of Brahmachal (modern-day Baramchal, Kulaura), Govardhan of Gour allowed Amar Singh to rule over southern Sylhet. Singh was unable to cope and died shortly after. The Kuki chiefs then annexed Brahmachal (Southern Sylhet) to the Twipra Kingdom ruled by Ratan Manikya. Jaidev Rai was appointed to govern Brahmachal under the Tripura king. The penultimate Raja Govardhan of Gour was killed in a battle against Kuki rebels and the Jaintia Kingdom in 1260. He would be succeeded by his nephew, Gour Govinda, who would reunite Northern Sylhet (Gour) and Southern Sylhet (Brahmachal). Govinda dismissed Govardhan's chief minister Madan Rai and appointed Mona Rai as his minister instead.

Medieval

Delhi Sultanate period

During the time of the Delhi Sultanate's conquest of Bengal, Sylhet continued to be made up of petty kingdoms. Ghiyasuddin Iwaz Shah, the governor of Bengal who later claimed independence from Delhi, carried out invasions into neighbouring regions such as Assam, Tripura, Bihar and Sylhet and making them his tributary states.[14] In 1254, Governor of Bengal Malik Ikhtiyaruddin Iuzbak invaded the Azmardan Raj (present-day Ajmiriganj). He defeated the local Raja, and plundered his wealth.[15]

The 14th century marked the beginning of an emerging Islamic influence in Sylhet. In 1303, the Sultan of Lakhnauti Shamsuddin Firoz Shah's army defeated the Hindu Raja Gour Govinda. This war began when Ghazi Burhanuddin, a Muslim living in Tultikar sacrificed a cow for his newborn son's aqiqah or celebration of birth.[16][17] Govinda, in a fury for what he saw as sacrilege, had the newborn killed as well as having Burhanuddin's right hand cut off.[18] The general's army was aided by a Sufi missionary, Shah Jalal, and his companions.[17] Chief minister Mona Rai was killed in the battle and Govinda fled with his family. The city of Srihatta was given the epithet Jalalabad (settlement of Jalal) under the Lakhnauti Sultanate.[19] Sikandar Khan Ghazi, one of the commanders of the battle and Firoz's nephew, was then made the first Muslim wazir to rule over Sylhet. Sikander ruled for a number of years under Shamsuddin Firoz Shah until his death, when he drowned while riding a boat.[11] He was succeeded by Haydar Ghazi, appointed by Shah Jalal himself.[20][21]

The Raja of Laur, Ramnath (descendant of Keshab Misra), had three sons with only one remaining in central Laur. Ramnath's second son, Durbar Khan, migrated to Jagannathpur to build his own palace. He later seized his youngest brother, Gobind Singh's, territory in Baniachong.[12]

Sonargaon rule

The Delhi Sultanate's control of Bengal gradually weakened as rebel governors declared independence. During the early 14th-century, Bengal was divided between three small sultanates- Sonargaon in the east, Lakhnauti in the west, and Satgaon in the south. Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah became the independent Sultan of eastern Bengal with a realm covering Sonargaon, Sylhet, and Chittagong. His kingdom was powerful enough to withstand the kingdoms of Arakan and Tripura. The Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta visited Sylhet during this period and met with Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah and Shah Jalal.[22] Fakhruddin was succeeded by his son Ikhtiyaruddin Ghazi Shah.[22]

Bengal Sultanate period

After the defeat of the last Sultans of Lakhnauti and Sonargaon between 1342 and 1352, Sylhet passed to the control of Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah who unified a wider region into the Bengal Sultanate. Bengali Muslims were exploiting the fertile land of Sylhet for agricultural production and enjoyed relative prosperity innovating a contemporary agrarian society. The Taraf Kingdom, founded by Syed Nasiruddin, was transformed into a hub of Islamic and linguistic education. Prominent writers and poets hailing from medieval Taraf and its surrounding areas included Syed Shah Israil (Sylhet's first author), Muhammad Arshad, Syed Pir Badshah and Syed Rayhan ad-Din. The region began to experience an influx of Muslim settlers, including Turks, Pashtuns, Arabs, and Persians.[23] After the death of Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah, Bengal was ruled by Sikandar Shah.

In 1384, a young Persian man by the name of Mirza Malik Muhammad Turani migrated to Sylhet with a large force and established the Pratapgarh Kingdom (also including Deorali and Bhanugach) after marrying the daughter of the local ruler who had no children to take the throne. The Kingdom was subordinate to the Maharaja Maha Manikya of the Manikya dynasty of Tripura.[24]

In 1437, Adwaitacharya was born in Nabagram, Laur Kingdom. Muqabil Khan was the Wazir of Sylhet in 1440. In 1463, Sylhet was governed by Khurshid Khan who built a mosque near Anair Haor in Hatkhola. Many mosques were built during this period such as an Adina Mosque replica in Dargah Mahalla built by Majlis Alam, the Dastur of Sylhet, in 1472. Alam also built the Goyghor Mosque in South Sylhet with his father, Musa ibn Haji Amir. Shankarpasha Shahi Masjid in Taraf as well as numerous dargah complexes commemorating Shah Jalal and his disciples were also built in this period. Alam was succeeded by Muqarrab ud-Daulah and Muazzam Khalis Khan respectively. In 1479, a mosque inscription in Tilapara, Muktarpur mentions another minister by the name of Malik Sikandar.

In addition, 1486 marked the birth of Chaitanya whose ancestral homes are in Golapganj and Baniachong. Hindus believe Chaitanya was a reincarnation of Krishna and will return during the Kholi Zug. In 1499, a Persian nobleman from Isfahan known as Prince Sakhi Salamat settled in a rural village in South Sylhet known as Prithimpassa (now located in Kulaura). Being a wealthy nobleman; his son, Ismail Khan Lodhi, was granted a jagir by the Mughals and given the status of Nawab in addition to other prestigious titles. In 1511, Alauddin Husain Shah's general Rukun Khan was made the governor of Sylhet. In 1512, Khan enlarged the dargah of Shah Jalal, according to an ancient Persian inscription.[25] Khan was succeeded by Gawhar Khan Aswari.

Bhanu Narayan of the Ita dynasty defeated a rebel of the Tripura Kingdom. The Tripura Raja then awarded him as the first raja of the Ita kingdom (Rajnagar), subordinate to the Kingdom.

In 1489, Pratapgarh ruler Turani's great-great-grandson Malik Pratap declared independence from the Tripura Kingdom whilst the Tripura Raja Pratap Manikya II was busy fighting a war against his elder brother, Dhanya. Malik then allied with the Tripura Raja in the war, and so Manikya formally recognised the independence of the Pratapgarh Kingdom and gave him the title of Raja.[26][27]

Raja Bazid of Pratapgarh, the grandson of Raja Malik Pratap, repulsed an invasion by the powerful neighbouring kingdom of Kachar. He then expanded the power and influence of his own kingdom, stretching its frontiers as far west as the borders of Jangalbari in Kishoreganj. In light of these achievements, Bazid gave himself the new title of Sultan, placing himself on the same level as the Sultan of Bengal Alauddin Husain Shah.[28]

The governor of Sylhet under the Bengal Sultanate, Gawhar Khan Aswari later passed away. His deputies, Subid Ram and Ramdas, took advantage of his death and embezzled a large amount of money from the state government before fleeing to Pratapgarh.[28] Sultan Bazid gave his protection to the two deputies and took advantage of Gawhar's death to seize Sylhet town into his kingdom.[29] Husain Shah then sent his minister, Sarwar Khan of Barsala, to negotiate with Pratapgarh and see if he can return Sylhet to Bengal.[30][28] After the rejection of Bazid, Surwar defeated him and his allies, the Zamindars of Ita and Kanihati, in battle.[31] Bazid was allowed to continue as ruler of Pratapgarh with relative independence, but he was required to surrender his control of Sylhet and give up the title of Sultan. A tribute of money and elephants was given to show Bazid's loyalty and Subid Ram and Ramdas, were sent to Hussain Shah to face punishment. Surwar Khan then became the Nawab of Sylhet, with Bazid's daughter Lavanyavati being given in marriage to Surwar's son and eventual successor, Mir Khan.[32][31]

Towards the end of the Sultanate era, Western Sylhet and Eastern Mymensingh became the Iqlim-e-Muazzamabad governed by Khawas Khan. Muazzamabad was originally founded by Shah Muazzam ad-Din Quraishi, the son of Shah Kamal Quhafa. Its capital was at Kamalshahi (Shaharpara) and also had a second administration at Nizgaon (Shologhar, Sunamganj Sadar). The Assamese claim that Chilarai of Kamata, the brother of King Nara Narayan, took over parts of the Sylhet region, including Jaintia Kingdom, in 1553. In this same time period, Taraf was subordinate to the Twipra Kingdom during the reign of Maharaja Amar Manikya. When Syed Musa, the ruler of Taraf, refused to provide labour for Manikya, a war took place in Jilkua, Chunarughat. Musa was backed by Fateh Khan, the Afghan zamindar of Sylhet. Taraf and Sylhet were briefly conquered by the Tripuris. Khwaja Usman would later capture Taraf and Uhar.

During the rule of the Kangleipak King Khagemba, the King's brother, Prince Shalungba, was disappointed with Khagemba's treatment so he fled to Taraf where he allied with the local Bengali Muslim leaders. With a contingent of Bengali Muslim soldiers under Muhammad Sani, Shalungba then attempted to invade Manipur but the soldiers were captured and made to work as labourers in Manipur. These soldiers married local Manipuri women and adapted to the Meitei language. They introduced hookah to Manipur and founded the Pangal or Manipuri Muslim community.[33]

Mughal period

The Mughal invasions and conquests in Bengal started during the reigns of Emperors Humayun and Akbar. The Battle of Rajmahal in 1576 led to the execution of Daud Khan Karrani, ending the Karrani sultanate. However, the Pashtuns and the local zamindars known as Baro Bhuyans led by Isa Khan, the ruler of Bhati, continued to resist the Mughal invasion. After the death of Isa in 1599, the Baro-Bhuyan confederacy started to weaken. The Ain-i-Akbari notes the prevalence of slaves, oranges, timber and singing birds in the region.[34] Bengal was integrated as a Mughal province known as the Bengal Subah by 1612 during the reign of Jahangir.[35] The Finance Minister of the latter emperor, Raja Todar Mal, estimated Sylhet to be worth £16,704 in 1582.[36] The Qanungoh (revenue collector) of Sylhet was assisted by pargana patowaris. Each pargana's revenue was collected by a choudhury.

However, even during the reigns of Jahangir and Shah Jahan, Mughal authority in Sylhet was still referred to as Bengal's Wild East due to the region becoming a refuge for the Afghan chieftains and other Baro-Bhuiyan insurgents. Khwaja Usman of Bokainagar, Mymensingh fled to Sylhet where he allied with the likes of Bayazid Karrani II of Sylhet, Anwar Khan of Baniachong, Pahlawan of Matang and Mahmud Khan.[3]

The final raja of the Ita Kingdom, Raja Subid Narayan, built his fort in the Barua Hills, which remains today as ruins. He is also known to have built more large ponds such as the Balda Sagar and Sagar Dighi initially for his daughter, Kamla Rani, and to make space for a palace. Subid lost a battle in 1610 in which South Sylhet became under the rule of Afghan chieftain Khwaja Usman. Usman's rule was interrupted after Mughal General Islam Khan I's attack in 1612 leading to complete Mughal control of Sylhet.[4] Ludi Khan was appointed the Amil of Sylhet. He was succeeded by his son, Jahan Khan who was a minor assisted by the Tehsildars of Taraf; Basu Das and Rajendra.[34]

In 1618, the Jaintia Raja Dhan Manik conquered Dimarua leading to a war with Maibong Raja Yasho Narayan Satrudaman of the Kachari Kingdom. Dhan Manik, realising that he would need assistance, gave his daughter in hand to Raja Susenghphaa of the Ahom kingdom. The Ahoms then fought the Kacharis allowing an easy escape for Dhan Manik and the Jaintians.[37]

Sylhet became a sarkar of the Bengal Subah. Its eight mahals/mahallahs included Pratapgarh-Panchakhanda, Bahua-Bajua, Jaintia (parts of Jaintia Kingdom), Habili (Sylhet), Sarail-Satra Khandal (North Tripura), Laur, Baniachong and Harinagar. Sylhet emerged as the Mughals' most significant imperial outpost in the east and its importance remained as such throughout the seventeenth century.[5] The sardars of Sylhet during Jahangir's reign included Mubariz Khan, Mukarram Khan, Mirak Bahadur Jalair, Sulayman Banarsi and his son, and Mirza Ahmad Beg. During the rebellion of Prince Khurram, Mirza Saleh Arghun - a relative of Khwaja Usman - was made the faujdar of Sylhet.

Muhammad Zaman Karori of Tehran was made the Amil of Sylhet by emperor Jahangir after the Emperor arrived to Bengal and punished the rebels. Zaman took part in Islam Khan I's Assam expedition and was instrumental to the capture of Koch Hajo. He later on became faujdar of Sylhet in 1636 by Shah Jahan and was made a mansabdar of 2,000 sowar.[38] In 1657, Shah Shuja, the Subahdar of Bengal, granted 50 bighas of land to zamindar Alam Tarib.

During the reign of Shah Jahan from 1628 to 1658, the faujdars were Muizz ad-Din Rizvi, Sohrab Khan and Sultan Nazar.

During the reign of Aurangzeb in the 17th century, the sarkar generated annual revenues of 167,000 takas.[24] Lutfullah Shirazi, the faujdar of Sylhet, established a strong enclosure in Shah Jalal's dargah in Sylhet town in 1660. Isfandiyar Khan Beg succeeded Shirazi in 1663 and was known to have destroyed Majlis Alam's Adina Mosque replica in Dargah Mahalla because the imam started Eid prayers without waiting for him. Following its destruction, Isfandiyar attempted to rebuild it. The mosque, located near the Dargah Gate, remains uncompleted today, hidden behind trees. The next faujdars were Syed Ibrahim Khan, Jan Muhammad Khan and Mahafata Khan.[34]

Farhad Khan was the most well-known of Sylhet's faujdars. He built Sylhet Shahi Eidgah, which still remains as the largest eidgah in the region today as well as numerous bridges across the Sarkar. He was succeeded by Sadeq Khan and then Inayetullah Khan.[39]

After the death of Laur Raja Durbar Khan, his younger brother Gobind Singh took over his land. Durbar Khan's sons then informed the Nawab of Murshidabad of this incident. Gobind was summoned to Delhi for a short time where he accepted Islam. As a reward, he was granted the title of Khan and regained Laur but as a feudal ruler.

Prince Azim-ush-Shan, the subahdar of Bengal, is said to have granted Hamid Khan faujdarship to Sylhet & Bundasil.[15] Rafiullah Khan, Ahmad Majid and Abdullah Shirazi were the faujdars of this period. Faujdar Karguzar Khan was known to have gifted land to Kamalakanta Bhattacharya of Ita in 1706. A year later, Karguzar was succeeded by Mutiullah Khan and then in Rahmat Khan in 1709. Emperor Farrukhsiyar appointed Talib Ali Khan as the next faujdar. After Farrukhsiyar's death, Talib was replaced by Shuja-ud-Din Muhammad Khan in 1719.

In the early 1700s, the Jaintia Raja Ram Singh kidnapped the Kachari Raja. The Raja of Cachar then informed Ahom Raja Rudra Singh Sukhrungphaa which led to the Ahoms attack through North Cachar and Jaintia Hills. Jaintia was annexed to the Ahoms and its capital city, Jaintiapur, was then raided by the Ahoms and thousands of innocent civilians were put to death or ears and noses were cut off. Sukhrungphaa then informed the Faujdar of Sylhet that Jaintia was under his rule and that it is him that they will trade to. However, the Ahom rule in Jaintia was weak and short-lived. The Jaintias rebelled in their own land defeating the Ahom soldiers. Ram Singh, however, died as a captive to the Ahoms and his son, Jayo Narayan took over the Jaintia Kingdom.[12]

In the middle of the seventeenth century, Babu Kabi Ballabh, a descendant of Sarbananda of Barsala, mastered the Persian language. After impressing Emperor Muhammad Shah, Ballabh was given the title of Rai. Ballabh was then made the Qanungoh and Dastidar of Sylhet by the Nawabs of Murshidabad.[40] The role of the Dastidars were to approve and seal the sanads. He was succeeded as Qanungoh and Dastidar by his son, Subid Rai who established a Dastidar family home which he named Subid Rai Gridha. Harkrishna Das was from his progeny. Das' mother sent him off to a fakir in Murshidabad who would educate him in the Sanskrit and Persian languages. He then assisted Rajballabh, the deputy of Nawazish Muhammad Khan, in writing an account on Bengal's revenue. After this service, the Nawab of Murshidabad granted Das Rs. 10,000 as a reward and carried on working in the Murshidabad court.

Emperor Muhammad Shah appointed Shukurullah Khan as the next Faujdar after Shuja. Although Shukurullah had good relations with the Naib Nazim of Dhaka, he did not get on well with the local authorities and was dismissed quickly. He was replaced by Harkrishna Das who became the 11th Nawab of Sylhet in late 1721. Nicknamed Mansur al-Mulk, Das was murdered in 1723 by his own men who are presumed to have been loyal to Shukurullah. Sylhet was then divided between three individuals; Naib Sadatullah Khan, Hargovinda Rai and Manik Chand. Shukurullah returned to his post as faujdar in 1723.[40] The last ruler of Muazzamabad, Hamid Khan Qureshi accepted the post of faujdar after Shukurullah.[41] In August 1698, he earned the title of Shamsher Khan after assisting the Nawab of Bengal, Murshid Quli Khan, in defeating Rahim Khan Afghan in Chandrakona.[42] Shamsher Khan had 6 naibs; Shuja ad-Din (previous faujdar), Basharat Khan, Syed Rafiullah Hasni of Rafinagar, Muhammad Hasan and Mir Ilyas Khan. Shamsher was killed in 1740 in the Battle of Giria alongside the Nawab of Bengal, Sarfaraz Khan.

The zamindar of Laur, Abid Reza, son of Gobind Khan, left Laur to establish Baniachong in the early eighteenth century, which would become the largest village in the world. Many followed Reza to Baniachong after Laur was burnt by the Khasi in 1744. The Nawab of Bengal Alivardi Khan is said to have granted 48 large boats to the Baniachong zamindars.[43] A short while after, Reza built a fort in Laur which remains as ruins today. His son, Umed Reza, excavated much of Baniachong during his zamindari. Both Rezas were feudal under the Amils or Faujdars of Sylhet.[12]

Alivardi Khan granted the deputy governor of Dhaka, Nawazish Muhammad Khan, to also govern Sylhet, Tripura and Chittagong.[15] The next faujdar was Bahram Khan. He gifted land to Bhattacharya of Shamshernagar in 1742. Bahram built the mosque located next to Shah Jalal's dargah in 1744. He appointed Muhammad Jan as his Naib. Bahram was succeeded by Ali Quli Baig of Alikulipur (near Badarpur). Baig's leadership was short and Naib Ali Khan became the next faujdar. Ali Khan granted land in 1748 to Kamala Kanta Bhattacharya of Lauta and Ram Chandra Vidyabagish of Dinajpur. He also granted land to Gangaram Siromani of Burunga in 1750.

Company rule

.JPG.webp)

In 1757, the Shyllong King Khasi Raja closed the Sonapur Duar, stopping trade between the Jaintia and Ahom kingdoms. An envoy of Jaintias assembled at Hajo where they informed the incident to Ahom Raja Suremphaa Swargadeo Rajeswar Singh who re-opened it for them.[12]

Sylhet came under British administration in 1765 and made a part of the Bengal Presidency. William Makepeace Thackeray was made the first Collector of Sylhet and he was followed by Mr Sumner. Sylhet was strategically important for the British in their pursuit of conquering Northeast India and Upper Burma. The British divided the region into four subdivisions further divided into collectory zilas and then parganas. The Qanungohs were abolished for a time during British rule and Wahdadars replaced Choudhuries as local revenue collectors. North Srihatta consisted of Parkul, Jaintiapur and Tajpur zilas. South Srihatta was made up of Rajnagar, Hingazia and Noyakhali. Habiganj was split into Nabiganj, Laskarpur and Shankarpasha. Sunamganj had one collectory zila at Ramulganj and Karimganj at Latu.[11] During this time, many Western European and Armenian traders migrated to Sylhet and are buried in Sylhet Sadar.[6]

Major Henniker led the first expedition to Jaintia in 1774. In 1778, after a short term by Mr Holland, the next collector was Robert Lindsay. A year into his office, the Khasi attacked the merchants of Pandua, Bholaganj (Companiganj) who were going towards Calcutta after experiencing abuse from other 'Europeans'. Many merchants pleaded Lindsay to build a small brick fort to protect them from further attacks from the Khasi.[12] During the same year, an auction took place in which a purchaser won estates in Balishira (South Sylhet). With the former owner refusing to give the land, a havildar and ten sepoys were sent to the estate to allow the purchaser his land. The former owner killed two officers and injured many. He then plundered two government boats worth over 2,000 rupees. Reinforcements were sent from Sylhet to Balishira, eventually forcing the former owner to flee. The former owner later returned with a large group of men and attacked the resistance, keeping some as hostage. The former officer and some of his men were later arrested by the authorities in Dacca.[12]

In 1782, the first ever uprising in the Indian subcontinent which was against the British rule, the Muharram Rebellion, took place in Sylhet Shahi Eidgah in which Lindsay killed two of the leaders of the rally, the Pirzada and Syed Muhammad Hadi, with his own pistol. The other leader, Syed Muhammad Mahdi was also killed in the conflict alongside other rebels.[44]

In 1783, the headquarters of a thana was attacked by Khasis who were provoked by a certain havildar. The Khasi chiefs demanded the havildar's head which Lindsay refused to give. Many casualties and deaths occurred on both sides, Lindsay's chunam works were plundered and his men were said to have been "cut into pieces".[44][12]

In 1786, the Revolt of Radharam took place in the Greater Pratapgarh. Zamindar Radha Ram plundered Chargola thana in Karimganj with the help of Kukis before escaping. Lindsay reacted by ordering for the burning of Radha Ram's village and the seizing of his cattle. It is said in another incident that the hill tribes attacked the Laur thana, killing 20 people including the thanadar. In 1787, the Khasis of Laur also rebelled, plundering many parganas, such as Atgram, Bangsikunda, Ramdigha, Betal and Selbaras, and killing up to 800 people. Before Lindsay's troops could arrive, the Khasis retreated back to their mountains.[44]

Hyndman succeeded Lindsay in late 1787 as the Collector of Sylhet but his term was extremely short and John Willes replaced him.[6] During Willes' office, the Khasi led by Ganga Singh plundered Ishamati thana and bazaar and killed a Bara-Chaudhri family. In 1789, Willes stationed many sepoys in Pandua (Companiganj). The Khasi however, continued their attacks, killing the thanadar and many sepoys. Two European merchants managed to escape and inform Willes of the incident, who passed it on to the Government at Calcutta. A force was then sent from there, to the village of Pandua although it led to a bloodless end. Willes also told the government that he really had little control over northern Sylhet as the Khasi chiefs refused every order, would behead the messenger and then continue raiding Sylheti villages as they had done even during the Mughal period. Another Khasi raid took place in 1795 and many years went after that with the Khasis remaining in their hills and not troubling the plains.[12] Willes also changed the administration of Sylhet into ten zillahs, further divided into 164 parganas as well as Kusbah Sylhet. Revenue was then collected by ten zillahdars assisted by the pargana patowaris. The currency of the Sylhet region was changed from cowries to silver coins. During his term, Laskarpur Pargana was also moved from Dacca to Sylhet. Courts were also being established in every zillah.[6]

In 1799, Agha Muhammad Reza invaded Cachar. With help of Nagas and Kukis, he was able to defeat the barqandaz sent by the Raja of the Kachari Kingdom, and expelled the Raja to the nearby hills. Reza also sent 1,200 men to attack the nearby thana of the East India Company, administered by one havildar and eight sepoys. The Kachari army then arrived with 300 men and two grasshopper cannons but were defeated. During this time, the British were able to gain a reinforcement of 70 sepoys. The army ended up in a brawl between the Kacharis, and the British sepoys eventually drove both groups back leading to 90 deaths in the Kachari side. Reza was later arrested.[11]

A border dispute started in 1807 between the Khaspur Raja of Cachar, Krishnachandra Narayan, and the Amin Muluk Chand in Badarpur. The Amin would lay down a line, only to find that the Kacharis would fill the ditch up and take all the crops. The Kacharis would also raid Chapghat pargana. The British ordered Badarpur's officer to prevent the intruders from this but they found out that the land in fact belonged to the Raja and not the Amin.

In 1821, a group of Jaintias kidnapped British subjects attempting to sacrifice them to Kali. A culprit was then found by the British who admitted that it was an annual tradition which the Jaintias have been doing for 10 years. The priest would cut off the victim's throat and then the Jaintia princess would bathe in his blood. The Jaintia believed that this would bless the princess with offspring. Upon hearing this, the British threatened the Jaintia Raja that they would invade his territories if this does not stop. The Raja made an agreement in 1824 with David Scott that they will only negotiate with the British. A year later, the Jaintias attempted to continue their annual sacrifice which they had previously agreed with the British that they would stop. During the First Anglo-Burmese War in the same year, British troops based themselves at Badarpur. They then advanced to Bikrampur in Cachar where they were defeated. In 1826, the Kukis of Pratapgarh King murdered a group of woodcutters and held three hostages after not receiving an annual gift from the Pratapgarh zamindars. The Kukis then sent one hostage to the British to tell them that they must pay a ransom to free the other two, in which the British agreed.

With the last Khasi raid taking place in 1795, the British experienced another attack in 1827 in Panduah leading to the death of a sepoy, postman and dhobi. The Agent to the Governor-General of India, William Amherst, was absent and so the Collector of Sylhet ordered his officer to retaliate with the Sylhet Light Infantry. After the Nongkhlao massacre in Kanta Kal village two years later, Captain Lister and the Infantry defeated the Nongkhlao Khasis, causing them to retreat and never attack the British or raid villages again.

Ganar Khan was the last Faujdar of Sylhet. During his office, two processions were being prepared by Sylhet's Muslim and Hindu communities respectively. The Islamic month of Muharram in the Sylhet's history was a lively time during which tazia processions were common. This happened to fall on the same day as the Hindu festival of Rothjatra (chariot procession). Sensing possible communal violence, Ganar Khan requested the Hindu community to delay their festival by one day. Contrary to the Khan's statement, a riot emerged between the two communities. During one of the riots, the King of Manipur Gambhir Singh was passing through the city of Sylhet whilst on a British expedition against the Khasis. As a Hindu himself, Singh managed to defend the Hindus and disperse the Muslim rioters with his Manipuri troops. The Rothjatra was not delayed, and the Manipuri king stayed to take part in it and was revered by the Hindu community as a defender of their faith.[45]

The Jaintias kidnapped four British men in 1832. Three were sacrificed in Great Hindu temple in Faljur, with one escaping and informing the British authorities of the atrocities.[6][46] After the Jaintia Raja declined to find the culprits, the British finally conquered the Jaintia Kingdom and incorporated it into the Sylhet District in 1835.[12] Also in 1835, pargana patowaris were replaced by zillah patowaris and muhuris.[6]

The East India Company first initiated their trading of tea in the hills of Sylhet.[47][48] The first commercial tea plantation in British India was opened in the Mulnicherra Estate in Sylhet in 1857.[49] The region started to emerge as the centre of tea cultivation in Bengal and major export. Many local entrepreneurs also started founding their own companies such as Syed Abdul Majid, Nawab Ali Amjad Khan, Muhammad Bakht Mazumdar, Ghulam Rabbani, Syed Ali Akbar Khandakar, Abdur Rasheed Choudhury and Karim Bakhsh.

In the anti-British Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, 300 sepoys who revolted against the British, looted the Chittagong Treasury and took shelter with Nawab Gaus Ali Khan of Prithimpassa.[50] The treasury remained under rebel control for several days. A rebellion also took place in Latu, Barlekha.

British Raj

Sylhet was constituted as a municipality in 1867.[51] Walton was made the Collector and Magistrate and he was assisted by William Kemble. Moulvi Dilwar Ali was the Deputy Collector.[6]

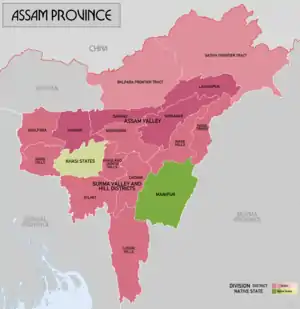

Assam Province (1874–1905)

Despite protests to the Viceroy from its Bengali-majority population, Sylhet was made part of the non-regulation Chief Commissioner's Province of Assam (Northeast Frontier Province) in September 1874 in order to facilitate Assam's commercial development.[52][53] A memorandum of protest against the transfer of Sylhet was submitted to the viceroy on 10 August 1874 by leaders of both the Hindu and Muslim communities.[54] The protests subsided when the Viceroy, Lord Northbrook, visited Sylhet to reassure the people that education and justice would be administered from Bengal,[55] and when the Sylheti people saw the opportunity of employment in tea estates in Assam and a market for their produce.[56]

The Assam Bengal Railway was established in 1892 to connect Assam and Sylhet with the port city of Chittagong and also served as a lifeline for the tea industry, transporting tea to exporters in the Port of Chittagong.[57][58] The first college in the region, Murari Chand College, was opened in 1892.[59][60]

The region was heavily affected during the 1897 Assam earthquake resulting in many deaths and the damage of many buildings as well as the Assam-Bengal Railway.[12] In 1903, snakes killed 75 people, wild pigs killed 2 people and a tiger killed one person.[12] Due to the size of Sylhet's Bengali Muslim majority, the All India Muslim League formed the first elected government in British Assam.

Eastern Bengal and Assam (1905–1912)

In 1905, Sylhet was added to the Chief Commissioner's Province of Eastern Bengal and Assam as a result of the Partition of Bengal. The new province, now ruled by a Lt. Governor, had its capital at Dhaka. Sylhet was incorporated into the province's Surma Valley Division. The province had a 15-member legislative council in which Assam had two seats. The members for these seats were recommended (not elected) by rotating groups of public bodies.

The partition was strongly protested in Bengal, and some people in Assam were not happy either. Opposition to partition was co-ordinated by Indian National Congress, whose President was then Sir Henry John Stedman Cotton who had been Chief Commissioner of Assam until he retired in 1902. The partition was finally annulled by an imperial decree in 1911, announced by the King-Emperor at the Delhi Durbar.[61]

Assam Province (1912–1947)

By the 1920s, organizations such as the Sylhet Peoples' Association and Sylhet-Bengal Reunion League (1920) mobilized public opinion demanding the division's incorporation into Bengal.[62] However, the leaders of the Reunion League, including Muhammad Bakht Mauzumdar and Syed Abdul Majid, later opposed the transfer of Sylhet and Cachar to Bengal during the Surma Valley Muslim Conference of September 1928. This was supported by the Anjuman-e-Islamia and Muslim Students Association.[63]

On 23 March 1922, an anti-British mob took place at a madrasa in Kanaighat. The madrasa was set to host their annual jalsa on the day but the British Raj had outlawed it and declared Section 144 throughout Kanaighat. The organisers were angered by the ban and subsequently violated Section 144 by leading a mob to attack the British commissioners. The armed British were able to conduct a swift victory, by shooting down six people and injuring 38 people.[64]

The numbers of lascars grew between the two world wars, with some ending up in the docks of London and Liverpool. During World War II, many fought on the Allied front before settling down in the United Kingdom, where they opened cafes and restaurants which became important hubs for the British Asian community.[65][66]

In 1946, Gopinath Bordoloi, the Prime Minister of British Assam brought forward his wish to hand over Sylhet back to East Bengal.[67] Following a referendum, almost all of erstwhile district of Sylhet became a part of East Bengal in the Dominion of Pakistan. After being pleaded by a delegation led by Abdul Matlib Mazumdar, a large part of Karimganj subdivision was barred and incorporated into the Dominion of India.[68][69] The referendum was held on 6 July 1947. 239,619 people voted to join East Bengal (i.e. part of Pakistan) and 184,041 voted to remain in Assam (i.e. part of India).[70] The referendum was acknowledged by Article 3 of the Indian Independence Act 1947.

Post-Partition of India

.jpg.webp)

In the early 20th century, during the British period, a labour exploitation system known as the "Nankar custom" was introduced and practiced by zamindars.[71] This barbarous system was confronted by the local peasants of the region during the Nankar Rebellion, leading to six deaths. In Beanibazar, the rebellion was born and spread across East Pakistan leading the Pakistani government to abolish the zamindari system and repeal the non-governmental rule to recognize the ownership of the land of peasants.[71][72]

In 1952, the Pakistan Tea Board - a tea research station in Srimangal, Moulvibazar - was founded to support the production, certification and exportation of the tea trade.[73][74]

Post Independence

During the Bangladesh Liberation War, when Pakistan Army created the 39th ad hoc Division in mid-November, from the 14th Division units deployed in those areas, to hold on to the Comilla and Noakhali districts, and the 14th Division was tasked to defend the Sylhet and Brahmanbaria areas only.[75] Sylhet was part of Sector 3, Sector 4 and Sector 5.

Sector 3 was headed by K. M. Shafiullah and later A. N. M. Nuruzzaman at Hejamara. It was formed by 2 East Bengal and EPR troops of Sylhet and Mymensingh. The ten sub-sectors of this sector (and their commanders) were: Asrambari (Captain Aziz, later replaced by Captain Ejaz); Baghaibari (Captain Aziz, later replaced by Captain Ejaz); Hatkata (Captain Matiur Rahman); Simla (Captain Matin); Panchabati (Captain Nasim); Mantala (Captain MSA Bhuyan); Vijoynagar (Captain MSA Bhuyan); Kalachhara (Lieutenant Majumdar); Kalkalia (Lieutenant Golam Helal Morshed); and Bamutia (Lieutenant Sayeed).

Sector 4 comprised from Habiganj to Kanaighat and had 4,000 EPR troops, and aided by 9,000 regular freedom fighters. They were commanded by Chitta Ranjan Dutta, and later Mohammad Abdur Rab. The headquarters of Sector 4 was initially at Karimganj and later at Masimpur in Assam. The six sub-sectors of this sector (and their commanders) were: Jalalpur (Masudur Rab Sadi); Barapunji (Mohammad Abdur Rab); Amlasid (Lieutenant Zahir); Kukital (Flight Lieutenant Kader, later replaced by Captain Shariful Haq); Kailas Shahar (Lieutenant Wakiuzzaman); and Kamalpur (Captain Enam).

Sector 5 comprised from Durgapur to Tamabil and was commanded by Major Mir Shawkat Ali at Banshtala. The sector was composed of 800 regulars and 5000 guerillas. The six sub-sectors of this sector (and their commanders) were: Muktapur (Subedar Nazir Hossain, freedom fighter Faruq was second in command); Dauki (Subedar Major BR Chowdhury); Shela (Captain Helal, who had two assistant commanders, Lieutenant Mahbubar Rahman and Lieutenant Abdur Rauf); Bholaganj (Lieutenant Taheruddin Akhunji who had Lieutenant SM Khaled as assistant commander); Balat (Subedar Ghani, later replaced by Captain Salauddin Mumtaz and Enamul Haq Chowdhury); and Barachhara (Captain Muslim Uddin).[76]

Amidst the war, many printing presses were damaged and this included the Sylheti Nagri script printed at the Islamia Press.[77][78] The region was a focal point of East Pakistan's Liberation War, which created Bangladesh. It was the hometown of General M. A. G. Osmani, the commander-in-chief of Bangladesh Forces and the Panchgaon Factory in Rajnagar Upazila produced cannons under his command. A famous historical cannon built by Janardan Karmakar remains in display in Dhaka.[10] The Battle of Gazipur, in Kulaura, raged between the Pakistani military and the allied forces of Bangladesh and India from 4 to 5 December 1971. The battle ended with a Bangladeshi victory. The Battle of Sylhet took place from 7 to 15 December, eventually leading to a Pakistani surrender and the liberation of Sylhet.[79] Pakistan Army's 93,000 troops unconditionally surrendered to the Bangladeshi Liberatiion Forces i.e, Mukti Bahini on 16 December 1971.[80] This day and event is commemorated as the Bijoy Dibos in Bangladesh.[81][80]

See also

References

- 1 2 Dilip K. Chakrabarti (1992). Ancient Bangladesh: A Study of the Archaeological Sources. Oxford University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-19-562879-1.

- ↑ Syed Umar Hayat (July–December 1996). "Bengal Under the Palas and Senas (750-1204)" (PDF). Pakistan Journal of History and Culture. 17 (2): 33.

- 1 2 Eaton, Richard. "Bengal under the Mughals: Mosque and Shrine in the Rural Landscape: The Religious Gentry of Sylhet". The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760.

- 1 2 Atul Chandra Roy (1968). History of Bengal: Mughal Period, 1526-1765 A.D. Nababharat Publishers.

- 1 2 Nath, Pratyay (28 June 2019). Climate of Conquest: War, Environment, and Empire in Mughal North India. Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 E M Lewis (1868). "Sylhet District". Principal Heads of the History and Statistics of the Dacca Division. Calcutta: Calcutta Central Press Company. pp. 281-326.

- ↑ Chowdhury, Iftekhar Ahmed (7 September 2018). "Sylhetis, Assamese, 'Bongal Kheda', and the rolling thunder in the east". The Daily Star. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ↑ Syed Umar Hayat (July–December 1996). "Bengal Under the Palas and Senas (750-1204)" (PDF). Pakistan Journal of History and Culture. 17 (2): 33.

- ↑ Kamalakanta Gupta (1967). Copper-Plates of Sylhet. Sylhet, East Pakistan: Lipika Enterprises. OCLC 462451888.

- 1 2 "Zila". Moulvibazar.com. January 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Sreehatter Itibritta – Purbangsho (A History of Sylhet), Part 2, Volume 1, Chapter 1, Achyut Charan Choudhury; Publisher: Mustafa Selim; Source publication, 2004

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 B C Allen (1905). Assam District Gazetteers. Vol. 2. Calcutta: Government of Assam.

- ↑ Muhammad Mojlum Khan (21 October 2013). The Muslim Heritage of Bengal: The Lives, Thoughts and Achievements of Great Muslim Scholars, Writers and Reformers of Bangladesh and West Bengal. Kube Publishing Limited. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-84774-062-5.

- ↑ KingListsFarEast Bengal

- 1 2 3 Stewart, Charles (1813). The History of Bengal. London: Black, Parry and Co.

- ↑ Hussain, M Sahul (2014). "Burhanuddin (R)". Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- 1 2 Muhammad Mojlum Khan (21 October 2013). The Muslim Heritage of Bengal: The Lives, Thoughts and Achievements of Great Muslim Scholars, Writers and Reformers of Bangladesh and West Bengal. Kube Publishing Limited. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-1-84774-062-5.

- ↑ EB, Suharwardy Yemani Sylheti, Shaikhul Mashaikh Hazrat Makhdum Ghazi Shaikh Jalaluddin Mujjarad, in Hanif, N. "Biographical Encyclopaedia of Sufis: Central Asia and Middle East. Vol. 2". Sarup & Sons, 2002. p.459

- ↑ Sylhet City. Bangla2000. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- ↑ "About the name Srihatta". Srihatta.com.bd. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ↑ Syed Murtaza Ali's History of Sylhet; Moinul Islam

- 1 2 Khan, Muazzam Hussain (2012). "Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ↑ Abu Musa Mohammad Arif Billah (2012). "Persian". In Sirajul Islam and Ahmed A. Jamal (ed.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- 1 2 Milton S. Sangma (1994). Essays on North-east India: Presented in Memory of Professor V. Venkata Rao. Indus Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7387-015-6.

- ↑ Hanif, N (2000). Biographical Encyclopaedia of Sufis: South Asia. pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Choudhury, Achyut Charan (1917). (in Bengali). Calcutta: Kotha. p. 474 – via Wikisource.

- ↑ R. M. Nath, The Back-ground of Assamese Culture (1978), p. 81

- 1 2 3 Choudhury (1917, p. 483)

- ↑ Subīra Kara, 1857 in North East: a reconstruction from folk and oral sources (2008), p. 135

- ↑ Milton S. Sangma, Essays on North-east India: Presented in Memory of Professor V. Venkata Rao (1994), p. 74

- 1 2 Bangladesh Itihas Samiti, Sylhet: History and Heritage, (1999), p. 715

- ↑ Choudhury (1917, p. 484)

- ↑ Nath, Rajmohan (1948). The back-ground of Assamese culture. A. K. Nath. p. 90.

- 1 2 3 Syed Mohammad Ali. "A chronology of Muslim faujdars of Sylhet". The Proceedings Of The All Pakistan History Conference. Vol. 1. Karachi: Pakistan Historical Society. pp. 275–284.

- ↑ Hasan, Perween (2007). Sultans and Mosques: The Early Muslim Architecture of Bangladesh. I.B. Tauris. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-84511-381-0.

It was only in 1612, during the reign of Jahangir, that all of Bengal was firmly integrated as a Mughal province and was administered by viceroys appointed by Delhi.

- ↑ Hunter, William Wilson (1875). "District of Sylhet: Administrative History". A Statistical Account of Assam. Vol. 2.

- ↑ Gogoi, Padmeshwar (1968). The Tai and the Tai kingdoms (Thesis). Gauhati University, Guwahati. pp. 333–335. ISBN 978-81-86416-80-8.

- ↑ Inayat Khan, Shah Jahan Nama, trans. A. R. Fuller, ed. W. E. Begley and Z. A. Desai (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1990), 235.

- ↑ Ali Ahmad. "Vide". Journal of Assam Research Society. VIH: 26.

- 1 2 Ghose, Lokenath (1881). "The Dastidar Family of Sylhet". The Modern History of the Indian Chiefs, Rajas, Zamindars, & C. Vol. Part II. pp. 483–484.

- ↑ Ali, Syed Murtaja, Hazrat Shah Jalal and Sylheter Itihas, 66: 1988

- ↑ Abu Musa Mohammad Arif Billah (2012). "Rahim Khan". In Sirajul Islam and Ahmed A. Jamal (ed.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ Hunter, William Wilson (1875). "District of Sylhet: Administrative History". A Statistical Account of Assam. 2.

- 1 2 3 Robert Lindsay (1840). "Anecdotes of an Indian life: Chapter VII". Lives of the Lindsays, or, A memoir of the House of Crawford and Balcarres. Vol. 4. Wigan: C.S. Simms.

- ↑ Singh, Moirangthem Kirti (1980). Religious Developments in Manipur in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Manipur State Kala Akademi. pp. 165–166.

Gonarkhan

- ↑ William Wilson Hunter (1886). The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Trübner & Company. p. 164.

- ↑ Colleen Taylor Sen (2004). Food Culture in India. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-313-32487-1.

- ↑ "Tea Industry". Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ "Tea cultivation". The Independent. 31 December 2017.

- ↑ "Rare 1857 reports on Bengal uprisings". The Times of India. 10 June 2009.

- ↑ "Sylhet City Corporation". Sylhet City Corporation. Archived from the original on 1 October 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ Tanweer Fazal (2013). Minority Nationalisms in South Asia. Routledge. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-1-317-96647-0.

- ↑ Hossain, Ashfaque (2013). "The Making and Unmaking of Assam-Bengal Borders and the Sylhet Referendum". Modern Asian Studies. 47 (1): 260. doi:10.1017/S0026749X1200056X. JSTOR 23359785. S2CID 145546471.

To make (the Province) financially viable, and to accede to demands from professional groups, (the colonial administration) decided in September 1874 to annex the Bengali-speaking and populous district of Sylhet.

- ↑ Hossain, Ashfaque (2013). "The Making and Unmaking of Assam-Bengal Borders and the Sylhet Referendum". Modern Asian Studies. 47 (1): 261. doi:10.1017/S0026749X1200056X. JSTOR 23359785. S2CID 145546471.

- ↑ Hossain, Ashfaque (2013). "The Making and Unmaking of Assam-Bengal Borders and the Sylhet Referendum". Modern Asian Studies. 47 (1): 262. doi:10.1017/S0026749X1200056X. JSTOR 23359785. S2CID 145546471.

It was also decided that education and justice would be administered from Calcutta University and the Calcutta High Court respectively.

- ↑ Hossain, Ashfaque (2013). "The Making and Unmaking of Assam-Bengal Borders and the Sylhet Referendum". Modern Asian Studies. 47 (1): 262. doi:10.1017/S0026749X1200056X. JSTOR 23359785. S2CID 145546471.

They could also see that the benefits conferred by the tea industry on the province would also prove profitable for them. For example, those who were literate were able to obtain numerous clerical and medical appointments in tea estates, and the demand for rice to feed the tea labourers noticeably augmented its price in Sylhet and Assam enabling the Zaminders (mostly Hindu) to dispose of their produce at a better price than would have been possible had they been obliged to export it to Bengal.

- ↑ Ishrat Alam; Syed Ejaz Hussain (2011). The Varied Facets of History: Essays in Honour of Aniruddha Ray. Primus Books. p. 273. ISBN 978-93-80607-16-0.

- ↑ Alan Warren (1 December 2011). Burma 1942: The Road from Rangoon to Mandalay. A&C Black. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-4411-0673-5.

- ↑ "Homepage". Sylhet MC College.

- ↑ Assam District Gazetteers - Supplement. Vol. 2. Shillong: The Assam Secretariat Press. 1915.

- ↑ William Cooke Taylor, A Popular History of British India. p. 505

- ↑ Tanweer Fazal (2013). Minority Nationalisms in South Asia. Routledge. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-1-317-96647-0.

- ↑ Bhuyan, Arun Chandra (2000). Nationalist Upsurge in Assam. Government of Assam.

- ↑ Roy, Jayanta Singh (2012). "Kanaighat Upazila". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ↑ Al-Mahmood, Syed Zain (19 December 2008). "Down the Surma – Origins of the Diaspora". Star Weekend Magazine. Vol. 7, no. 49. The Daily Star. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ↑ Bengali speaking community in the Port of London PortCities London. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ↑ Daniyal, Shoaib (24 June 2016). "With Brexit a reality, a look back at six Indian referendums (and one that never happened)". Scroll.in. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ "History - British History in depth: The Hidden Story of Partition and its Legacies". BBC. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ Chowdhury, Dewan Nurul Anwar Husain. "Sylhet Referendum, 1947". Banglapedia. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ "Sylhet (Assam) to join East Pakistan". Keesing's Record of World Events. July 1947. p. 8722. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013.

- 1 2 নানকার বিদ্রোহ. The Daily Kalerkantho (in Bengali). November 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ আমাদের নগরী (in Bengali). The Daily SCC. Retrieved 10 July 2017 – via Govt. website.

- ↑ Bangladesh Tea Research Institute, Banglapedia

- ↑ Chen, Liang; Apostolides, Zeno; Chen, Zong-Mao (2012). Global Tea Breeding: Achievements, Challenges and Perspectives. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-3-642-31877-1.

- ↑ Salik, Siddiq, Witness to Surrender, pp126

- ↑ Syeda Momtaz Sheren (2012). "War of Liberation, The". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ↑ Banglapedia

- ↑ Azam, Md. Ali (1939). Life Of Maulavi Abdul Karim. Calcutta: M. A. Azam.

- ↑ Dummett, Mark (16 December 2011). "How one newspaper report changed world history". BBC News. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- 1 2 "Why Do India Celebrate 'Vijay Diwas' On 16th December". SSBToSuccess. 17 December 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ "About us". Liberation War Museum. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

Further reading

- Abdul Karim. Social History Of The Muslims In Bengal (Down to A.D. 1538). Dacca: The Asiatic Society of Pakistan, 1959.

- Ali, Syed Murtaza. Hazrat Shah Jalal O Sylheter Itihas (Hazrat Shah Jalal and the History of Sylhet) Dacca, 1965.

- Chakrabarty, Bidyut. “The ‘Hut’ and the ‘Axe’: The 1947 Sylhet Referendum.” The Indian economic and social history review 39, no. 4 (2002): 317–350.

- Chakrabarti, Dilip Ancient Bangladesh: A Study of the Archaeological Sources Delhi: Oxford University Press 1992

- Fazakarley, Jed. “Multiculturalism’s Categories and Transnational Ties: The Bangladeshi Campaign for Independence in Britain, 1971.” Immigrants & minorities 34, no. 1 (2016), 49–69.

- Fedorowich, Kent, Andrew Thompson, Keith Povey, and John M MacKenzie. “Resistance and Accommodation in Christian Mission: Welsh Presbyterianism in Sylhet, Eastern Bengal, 1860–1940: Aled Jones.” In Empire, Migration and Identity in the British World. United Kingdom: Manchester University Press, 2013.

- Hossain, Ashfaque. “The Making and Unmaking of Assam-Bengal Borders and the Sylhet Referendum.” Modern Asian studies 47, no. 1 (2013), 250–287

- Hossain, Ashfaque. “The World of the Sylheti Seamen in the Age of Empire, from the Late Eighteenth Century to 1947.” Journal of global history 9, no. 3 (2014): 425–446.

- Hossain, Ashfaque. “Historical Globalization and Its Effects: a Study of Sylhet and Its People, 1874-1971”. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2009.

- Khan, Muhammad Mojlum. Muslim Heritage of Bengal : the Lives, Thoughts and Achievements of Great Muslim Scholars, Writers and Reformers of Bangladesh and West Bengal. Leicestershire: Kube Publishing, 2013.

- Ludden, David. “Investing in Nature Around Sylhet: An Excursion into Geographical History.” Economic and political weekly 38, no. 48 (2003): 5080–5088.

- Van Schendel, Willem. A history of Bangladesh (Cambridge University Press, 2009).