Holderness, New Hampshire | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Squam Lake c. 1910 | |

Seal | |

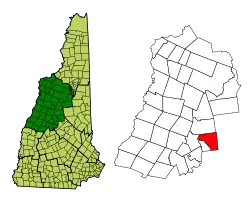

Location in Grafton County, New Hampshire | |

| Coordinates: 43°43′52″N 71°35′18″W / 43.73111°N 71.58833°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New Hampshire |

| County | Grafton |

| Incorporated | 1761 |

| Named for | Robert Darcy, 4th Earl of Holderness |

| Villages | Holderness East Holderness |

| Government | |

| • Select Board |

|

| • Town Administrator | Michael Capone |

| Area | |

| • Total | 35.7 sq mi (92.5 km2) |

| • Land | 30.3 sq mi (78.6 km2) |

| • Water | 5.4 sq mi (13.9 km2) 15.05% |

| Elevation | 584 ft (178 m) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

| • Total | 2,004 |

| • Density | 66/sq mi (25.5/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP code | 03245 |

| Area code | 603 |

| FIPS code | 33-36900 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0873627 |

| Website | www |

Holderness is a town in Grafton County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 2,004 at the 2020 census.[2] An agricultural and resort area, Holderness is home to the Squam Lakes Natural Science Center and is located on Squam Lake. Holderness is also home to Holderness School, a co-educational college-preparatory boarding school.

History

The Squam Lakes were a trade route for Abenaki Indians and early European settlers, who traveled the Squam River to the Pemigewasset River, then to the Merrimack River and seacoast. In 1751, Thomas Shepard submitted a petition on behalf of 64 grantees to colonial Governor Benning Wentworth for 6 miles square on the Pemigewasset River. The governing council accepted, and the town was named after Robert Darcy, 4th Earl of Holderness. The French and Indian War, however, prevented settlement until after the 1759 Fall of Quebec. The land was regranted as "New Holderness" in 1761 to a group of New England families, and first settled in 1763. As proprietor of half the town, Samuel Livermore intended to create at New Holderness a great estate patterned after those of the English countryside. By 1790, the town had 329 residents, and in 1816, "New" was dropped from its name.[3]

Holderness became a farming and fishing community, except for the "business or flat iron area" located on the Squam River, which has falls that drop about 112 feet (34 m) before meeting the Pemigewasset River. With water power to operate mills, the southwestern corner of town developed into an industrial center, to which the Boston, Concord & Montreal Railroad entered in 1849. But the mill village would be at odds with the agricultural community, especially when denied civic amenities including gaslights and sidewalks. Consequently, in 1868, it was set off as Ashland.[3]

Tourists in the 19th century discovered the region's scenic mountains and lakes. Before the age of automobiles, they would depart the train in Ashland and board a steamer, which traveled up the Squam River to rustic fishing camps or hillside hotels beside Squam Lake. Today, Holderness remains a popular resort area, where in 1981 the movie On Golden Pond was filmed.

In 1924, pioneer ornithologist Katharine (Clark) Harding Day studied a breeding population of the veery (Catharus fuscescens) in Holderness.[4][5]

Carne's Island c. 1910

Carne's Island c. 1910 Steamer Halcyon c. 1910

Steamer Halcyon c. 1910 Asquam House in 1912. A "high-class modern hotel on Shepherd Hill on the shores of Asquam Lakes".[6]

Asquam House in 1912. A "high-class modern hotel on Shepherd Hill on the shores of Asquam Lakes".[6]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 35.7 square miles (92.5 km2), of which 30.3 square miles (78.6 km2) are land and 5.4 square miles (13.9 km2) are water, comprising 15.05% of the town.[1] Bounded on the northwest by the Pemigewasset River, Holderness is drained by Owl Brook and the Squam River. Part of Squam Lake is in the east, and Little Squam Lake is in the center. Mount Prospect, with an elevation of 2,064 feet (629 m) above sea level, is in the north. The highest point in Holderness is Mount Webster in the northeast part of the town, elevation 2,076 feet (633 m) and part of the Squam Range. Via the Pemigewasset River, Holderness lies fully within the Merrimack River watershed.[7]

The town is served by U.S. Route 3 and state routes 25, 113 and 175.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 329 | — | |

| 1800 | 531 | 61.4% | |

| 1810 | 835 | 57.3% | |

| 1820 | 1,160 | 38.9% | |

| 1830 | 1,429 | 23.2% | |

| 1840 | 1,528 | 6.9% | |

| 1850 | 1,744 | 14.1% | |

| 1860 | 1,765 | 1.2% | |

| 1870 | 793 | −55.1% | |

| 1880 | 703 | −11.3% | |

| 1890 | 595 | −15.4% | |

| 1900 | 662 | 11.3% | |

| 1910 | 652 | −1.5% | |

| 1920 | 602 | −7.7% | |

| 1930 | 644 | 7.0% | |

| 1940 | 735 | 14.1% | |

| 1950 | 731 | −0.5% | |

| 1960 | 749 | 2.5% | |

| 1970 | 1,048 | 39.9% | |

| 1980 | 1,586 | 51.3% | |

| 1990 | 1,694 | 6.8% | |

| 2000 | 1,930 | 13.9% | |

| 2010 | 2,108 | 9.2% | |

| 2020 | 2,004 | −4.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[2][8] | |||

As of the census[9] of 2000, there were 1,930 people, 768 households, and 546 families residing in the town. The population density was 63.5 inhabitants per square mile (24.5/km2). There were 1,208 housing units at an average density of 39.8 per square mile (15.4/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 97.88% White, 0.47% African American, 0.05% Native American, 0.36% Asian, 0.10% from other races, and 1.14% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.41% of the population.

There were 768 households, out of which 30.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 61.2% were married couples living together, 5.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 28.9% were non-families. 21.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.48 and the average family size was 2.91.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 24.4% under the age of 18, 6.9% from 18 to 24, 24.5% from 25 to 44, 31.4% from 45 to 64, and 12.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 98.8 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $47,895, and the median income for a family was $55,526. Males had a median income of $36,500 versus $26,116 for females. The per capita income for the town was $27,825. About 2.8% of families and 4.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.2% of those under age 18 and 4.0% of those age 65 or over.

Town government

Holderness is governed in the traditional New England style, with a five-member board of selectmen as its executive branch, and the traditional town meeting as its legislative branch. Municipal elections and town meetings are customarily held in March.

Notable people

- George Butler (1943–2021), documentary filmmaker (Pumping Iron, The Endurance)[10]

- Moses Cheney (1793–1875), abolitionist, conductor on Underground Railroad[11]

- Oren B. Cheney (1816–1903), founder of Bates College[12]

- Arthur Livermore (1766–1853), US congressman[13]

- Samuel Livermore (1732–1803), US senator[14]

- Hercules Mooney (1715–1800), officer in the Continental Army[15]

- Lorenzo L. Shaw (1828–1907), mill owner[16]

- May Rogers Webster (1873–1938), naturalist, founded Lost River Conservation Camp near her summer home in Holderness[17]

Sites of interest

The town has multiple properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places:

- Boulderwood, a private summer camp

- Burleigh Brae and Webster Boathouse

- Camp Carnes, a private summer camp

- Camp Ossipee, a private summer camp

- Chapel of the Holy Cross

- Chocorua Island Chapel

- Holderness Free Library

- Holderness Inn

- North Holderness Freewill Baptist Church–Holderness Historical Society Building

- Rockywold–Deephaven Camps

- Shepard Hill Historic District

- Trinity Church

- True Farm

- Watch Rock Camp, a private summer camp

- Webster Estate

References

- 1 2 "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files – New Hampshire". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Holderness town, Grafton County, New Hampshire: 2020 DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- 1 2 Coolidge, Austin J.; John B. Mansfield (1859). A History and Description of New England. Boston, Massachusetts: A.J. Coolidge. pp. 529–530.

coolidge mansfield history description new england 1859.

- ↑ Harding, Katherine C. (1925). "Semi-Colonization of Veeries". Bulletin of the Northeastern Bird-Banding Association. 1 (1): 4–7. ISSN 2375-5091. JSTOR 43043331.

- ↑ Day, Katharine C. (1953). "Home Life of the Veery". Bird-Banding. 24 (3): 100–106. doi:10.2307/4510427. ISSN 0006-3630. JSTOR 4510427.

- ↑ "The Asquaum House". The Independent. July 6, 1914. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ↑ Foster, Debra H.; Batorfalvy, Tatianna N.; Medalie, Laura (1995). Water Use in New Hampshire: An Activities Guide for Teachers. U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Geological Survey.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "George Butler". 2014 FOX News Network, LLC. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ↑ Metcalf, Henry Harrison and McClintock, John Norris (1879). The Granite Monthly: A Magazine of Literature, History and State Progress, Volume 3. J.N. McClintock. p. 65.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Oren B. Cheney". Bates College. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ↑ "LIVERMORE, Arthur, (1766 - 1853)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ↑ "LIVERMORE, Samuel, (1732 - 1803)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ↑ "Hercules Mooney". 2009 Ancestry.com. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ↑ Yarmouth Revisited, Amy Aldredge (2013) ISBN 0738599034

- ↑ Dan True, Hummingbirds of North America: Attracting, Feeding, and Photographing (University of New Mexico Press 1995): 82-83. ISBN 9780826315724

Further reading

- "Historical and Cultural Resources Chapter" (PDF). Holderness Master Plan. Town of Holderness Planning Board. August 20, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2020.