| Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney | |

|---|---|

Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney | |

| Location | Macquarie Street, Sydney, City of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°52′09″S 151°12′46″E / 33.8693°S 151.2128°E[1] |

| Built | 1811–1819 |

| Architect | Francis Greenway |

| Owner | Sydney Living Museums |

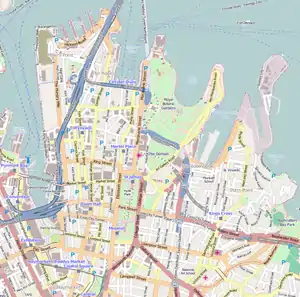

Location in Sydney central business district | |

| Type | Historic building |

| Area | 2.16 hectares (5.3 acres)[1] |

| Status | Open daily 10.00am – 5.00pm (Closed Good Friday and Christmas Day) |

| Website | Hyde Park Barracks Website |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iv, vi |

| Designated | 2010 (34th session) |

| Part of | Australian Convict Sites |

| Reference no. | 1306 |

| Region | Asia-Pacific |

| Official name | Hyde Park Barracks, Macquarie St, Sydney, NSW, Australia |

| Type | Historic |

| Criteria | a., b., h. |

| Designated | 1 August 2007 |

| Reference no. | 105935 |

| Place File No. | 1/12/036/0105 |

| Official name | Mint Building and Hyde Park Barracks Group; Rum Hospital; Royal Mint – Sydney Branch; Sydney Infirmary and Dispensary; Queen's Square Courts; Queen's Square |

| Type | State heritage (complex / group) |

| Criteria | a., c., d., e., f. |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Part of | Mint Building and Hyde Park Barracks Group |

| Reference no. | 190 |

| Type | Other – Government & Administration |

| Category | Government and Administration |

| Builders | Francis Greenway |

The Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney is a heritage-listed former barracks, hospital, convict accommodation, mint and courthouse and now museum and cafe located at Macquarie Street in the Sydney central business district, in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. Originally constructed between 1817 and 1819 as a brick building and compound to house convict men and boys, it was designed by convict architect Francis Greenway.[2] It is also known as the Mint Building and Hyde Park Barracks Group and Rum Hospital; Royal Mint – Sydney Branch; Sydney Infirmary and Dispensary; Queen's Square Courts; Queen's Square. The site is managed by the Sydney Living Museums, an agency of the Government of New South Wales, as a living history museum open to the public.

The site is inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as one of 11 pre-eminent Australian Convict Sites[3] as amongst "the best surviving examples of large-scale convict transportation and the colonial expansion of European powers through the presence and labour of convicts",[4][5] and was listed on the Australian National Heritage List on 1 August 2007,[6] and on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[7]

The historic site was closed in January 2019 for $18 million restoration work to transform it into "a rich new, immersive visitor experience like no other in Australia"[8] and reopened in February 2020.[9]

History

Hyde Park Barracks

Governor Macquarie, after his arrival in Sydney, had become increasingly disturbed by the male convicts' behaviour in the streets after work. Convicts had been allowed to find their own lodgings, however, Macquarie thought that barracks accommodation would improve the moral character of the men and increase their productivity. To this end, Macquarie requested convict architect Francis Greenway design barracks for 600 men. Constructed by convicts, the foundation stone was laid by Macquarie on 6 April 1817 and the barracks were completed in 1819. Macquarie was so impressed by Greenway's design that he granted him a full pardon shortly after its completion.[7] The barracks officially opened on 4 June 1819, when 589 convicts were admitted.[10]

Internally, the four rooms on each floor were hung with two rows of hammocks, with a 0.9-metre (3-foot) passage. The room allowed for each hammock was 2.1 by 0.6 metres (7 by 2 feet). In this way, the long eastern rooms could sleep 70 men each, while 35 men slept in the smaller western rooms.[7]

Francis Greenway was the architect who designed the Barracks. He was a convict for forging signatures and he had to move to Australia. He was also known for his architectural skills and quickly advertised himself in local places.

Macquarie was happy to note that since the confinement of the male convicts to the Barracks at night "not a tenth part of the former Night Robberies and Burglaries" occurred.[11] Commissioner Bigge, however, complained that the congregation of such a large number of "depraved and desperate characters" in one area had just condensed the problem.[11] Stealing was rife within the Barracks, items being passed over the walls to waiting accomplices for disposal. In an attempt to curb the thefts convicts were searched at the gates and broad arrows were painted on items of clothing and bedding.[7]

The accommodation soon proved inadequate and up to 1400 men were housed in the Barracks at any one time. It has been estimated that perhaps 30,000 men and boys passed through the Barracks between 1819 and 1848.[12] The convict response to the Barracks was somewhat mixed: those that were able to pay for lodgings by working on Saturday were not happy about the confinement; others were happy to have a roof over their heads. In 1820, in order to ease the pressure on the crowded Barracks the reward of being allowed to live outside the Barracks was extended. Convicts found gambling, drunk, engaged in street violence, or other unseemly behaviour had this freedom revoked and were sent to live in the Barracks. It had become a form of punishment. Loitering or idling on a Saturday was also punishable by confinement to the Barracks. Convicts had a peculiar mix of detention and freedom, convicts had to work for the Government during the week, but were allowed to work for their own benefits on Saturdays. This was a privilege Governor Macquarie did not like to see abused.[7]

From 1830, convicts were brought to the site for sentencing and punishment by the Court of General Sessions sitting in northern perimeter buildings. Punishments handed down included floggings, which were carried out onsite, or terms on the treadmill or chain gangs. While one of the first agencies to encroach on the Barracks, they were not the last. The Board for the Assignment of Servants operating from the Barracks between 1831 and 1841.[7]

The cessation of convict transportation in 1840 saw a dwindling number of convicts to house. By 1848, the numbers remaining did not warrant the use of such a large premise and the remaining convicts were removed to Cockatoo Island. The Barracks became instead the Female Immigration Depot. Occupying the first two floors, the Depot had the purpose of giving temporary shelter to newly arrived single females while they were found positions. Depending on the arrival of ships, the Depot could be overcrowded or almost vacant. Single women were encouraged to immigrate to address labour shortages, particularly for maids and servants, and the gender imbalance evident in the Colony. Women from Ireland, devastated by the Great Famine, were particularly targeted for immigration, coaxed to leave their homeland by the promise of better employment prospects and life. Additionally, the Barracks also housed the Orphan Institution until 1852, through which many more Irish famine victims passed. The perimeter buildings were taken over by a variety of government agencies including, but not limited to, the Government Printing Office (1848–1856), Stamp Office (1856), Department of the Chief Inspector of Distilleries (1856–1860) and the Vaccine Institute (1857–1886).[7]

The Asylum for Infirm and Destitute Women used the top floor, between 1862 and 1886, to provide accommodation and care to 150 women with terminal illnesses who could not afford medical treatment, the senile, insane, and generally destitute women. Both the Asylum and the Immigration Depot were managed by Matron Lucy Applewhaite-Hicks, who lived on the second floor with her family. Overcrowding was a constant problem, and the Barracks ceased to provide accommodation in 1886 when the women were moved to new purpose-built facilities at Newington[13][7]

The Courts continued to expand their use of the former Barracks buildings and by the early 19th century had almost exclusive use of the site. Courts were shuffled between buildings on the site and moved elsewhere in the city as more appropriate facilities were found or as pressures on space requirements grew or shrank. The new social policies of the 1880s saw the creation of a raft of legally specialised courts, which, in commemoration of the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria (1887) and 100 years of settlement in Sydney (1888), were consolidated in the Hyde Park Barracks.[14] The facility became known as Chancery Square, later the Queen's Square Courts. Extensive modifications were undertaken to accommodate the courts, including the addition of fibro buildings in the courtyard and internal divisions to the Principle Dormitory to convert it into courts.[7]

The courts occupying the site represent "all facets of the new phases of state intervention in personal and property relations",[15] a sample of which includes: the Court of Requests (1856–1859), the Sydney District Court (1858–1978), the City Coroner (1864–1907), Supreme Court Judges (1887–1970), Bankruptcy Court (1888–1914), Clerk of the Peace (1888–1903, 1915–1961), Curator of Intestate Estates (1888–1913), Probate Court and Offices (1893–1915), Court of Review (1901–1938), Court of Marine Enquiry (1901–1979), NSW Registrar & Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Court (1908–1914), Industrial Court (1911–1914), Industrial Arbitration Court (1912–1927), Legal Aid Office (1919–1944), Profiteering Prevention Court (1921–1922), Land and Valuation Court (1922–1956, 1976–1979), Court Reporting Branch (1944–1964).[16][7]

During the early 20th century, industrial relations dominated proceedings at Queen's Square. Two landmark decisions were handed down by the Courts while in the buildings: in 1927 the basic living wage was approved; in 1921 a case for equal pay for women was presented and rejected, to be granted only in 1973.[14][7]

In 1975, the Department of Public Works began extensive conservation works on the buildings. During these works, one of the first Permanent Conservation Orders, under the 1977 Heritage Act, was given to the Barracks in 1981. The conservation works were completed in 1984 and the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences opened a museum of Sydney. This museum operated until 1990 when ownership was transferred to the Historic Houses Trust of NSW (now Sydney Living Museums). The museum underwent refurbishment and further conservation works were undertaken, becoming a museum of the site, dedicated to interpreting how the site has developed, been used by multiple occupants and the physical evidence of their presence.[7] During 2019 Hyde Park Barracks was closed while a new exhibition space was developed. The exhibition space has a diminished focus on the significant role of Lachlan Macquarie. The site reopened in 2019.

The Friends of the Historic Houses Trust have been responsible for fundraising through interpretive tours and events to acquire the Neville Locker collection of convict artefacts for Hyde Park Barracks.[17][7]

The Mint

Governor Macquarie signed an agreement with Garnham Blaxcell, Alexander Riley and D'Arcy Wentworth to build a new convict hospital in November 1810. In return, the three gentlemen received the monopoly on the purchase of spirits for three years. As a result, the building became known as the Rum Hospital.[7]

While the architect is unknown, the inspiration for the form of the buildings is thought to have come from Macquarie's time in India, especially the Madras Government House. The Hospital, however, is constructed to the standard institutional army plan of the time – as seen at Victoria Barracks. The Hospital was originally constructed with three wings, the northern wing is now part of Parliament House, the central wing has been demolished and the southern wing became the Mint.[7]

The Legislative Council of New South Wales had begun petitioning the British Government for the establishment of a Mint in 1851. The gold rush had brought in to circulation large amounts of unrefined gold that was threatening the official currency. The British Government finally approved the establishment of a Mint in 1853, sending equipment and twenty staff.[7] The Mint began operation on 14 May 1855. Now known simply as The Mint, its official title was the Royal Mint, Sydney Branch. The first five years of operation saw exports of gold fall sharply as over one million pounds worth of gold was converted into sovereign and half sovereign coins each year. In 1868, Sydney's coins were recognised as legal tender in all British colonies, but it was not until February 1886 that they were accepted in Britain. The coins were identical to those produced in Britain, except for a small mint mark.[7] Federation encouraged the consolidation of minting activities in Canberra, Melbourne and Perth, the facilities in Sydney deteriorated to such an extent that the Mint was closed in January 1927, due to ageing equipment and unprofitability.[18][7]

On the departure of the Mint a series of government departments sought office space in the buildings. Similar to the Barracks next door, with no security of tenure there was little incentive to maintain the buildings and, instead fibro buildings filled all available spaces to meet the requirements of the Family Endowment Department (1927–1940), State Headquarters of National Emergency Service (1940–1950s), Housing Commission of NSW (mid 1940s) and the Land Tax Office (mid 1940s). The Court Reporting Branch, District Courts and Parliamentary Library moved in during the 1950s. Fibro-lined courtrooms were created within the former Coining Factory for use by them.[7]

In the 1930s, with increasing use of the motor car, and demand for parking spaces, the Mint's Macquarie Street gates were removed, a common fate for the gates of public buildings at the time. They were eventually acquired by Barker College at Hornsby in 1937 following the efforts of its Council Chairman, Sir John Butters. This was not the first time a school had acquired significant city gates: St. Joseph's College at Hunters Hill had bought the Sydney Town Hall gates and fencing when they became redundant with construction of Town Hall Railway Station.[18][7] Restoration of the buildings, announced in 1975, were undertaken in 1977-79, with the intended purpose of utilising at least the Mint as a Museum. In 1982 the Mint opened as a branch of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences.[7]

In 1998, ownership of the site was transferred to the Historic Houses Trust, who continued to operate a small museum, plus a cafe. In 2004 restoration and construction was undertaken to enable the HHT to use the site as a Head Office. The former Coining Factory was sympathetically remodelled into offices and the Superintendent's Office to hold the Caroline Simpson Library and Research Collection. A new theatrette and foyer were also added. The work was overseen by architect Richard Francis-Jones, of FJMT Architects; Clive Lucas Stapleton and Partners as conservation architects and Godden Mackay Logan as archaeologists.[7] In July 2016 the Mint celebrated its 200th anniversary of continuous civic function with a symposium "A future for the past" as part of a programme of events.[19][7]

Description

The Hyde Park Barracks are located in Queen's Square on the corner of Macquarie Street and Prince Albert Road, Sydney. The complex is bounded by high walls on the south and western sides. The northern and eastern boundaries are marked by ranges of structures. Located in the middle of the enclosure is the Principal Barracks or Dormitory Block. Near the north eastern and north western corners of the Dormitory Block are two weeping lillypillys (Waterhousia floribunda). The remainder of the gravelled courtyard is interspersed with sandstone pathways to facilitate disabled access. The major elements, namely the Dormitory Block, Northern Perimeter and Eastern Perimeter structures are discussed separately below in more detail.[7]

Principal Barracks/Dormitory Block

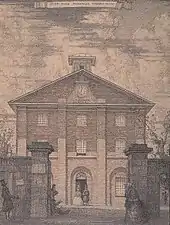

The main building is a three-storey sandstock brick, gabled former convict barracks of Georgian style. It has sandstone foundations, sills and string courses, while the pedimented gable is decorated by a shaped stone panel containing an early colonial clock.[20] The clock is surmounted by a crown and inscribed "L.Macquarie Esq., Governor 1817".[21] The pedimented temple form of the front is divided horizontally by a string course at the first and attic floors, and vertically by simple piers or pilasters, finished by Greenway's distinctive "double string course" beneath the eaves; relieving arches implying an arcade to the basement storey; shallow overhanging domes to the roof ventilator, lodges and corner pavilions; shaped blocking courses of the cornices of the pavilions and circular niches.[22][7]

The facade is simple but elegant and divided by brick pilasters and arched recesses to the ground floor. The central door has a semi-circular fanlight above, while the windows, 24 panes to ground and first floors and 16 panes to the second floor have flat lintels.[20][7]

During the late 1980s, concerted efforts were made to return the Barracks to their appearance c. 1820. External doorways made to access the now demolished court buildings have been carefully in-filled and it is now difficult to determine where some of these openings were. The stone string courses and sills are replacements, as is the shingling on the roof. By necessity, new joinery for doors and windows was constructed.[7]

Internally, partitions have been removed, again in an attempt to reveal Greenway's original design. The floor plan of all three levels is essentially identical, consisting of four rooms opening off two corridors forming a cross, the two rooms to the west being slightly smaller. Two stairwells provide access between the levels, the first in the north eastern corner and the second, also abutting the northern wall, in the hallway crossing the Barracks north/south.[7]

Restoration works were unable to remove all evidence relating to District Court, some fireplaces, doorways and transom lights are now "unusually placed".[23] The door joinery shows evidence of the successive adaptations to the building during its use as a Court. The skirtings, architraves, doors and windows represent two periods - c. 1884–1887 and c. 1980. The upper flights of the staircases are thought to be original, the lower flights being interspersed with Victorian repairs. The internal structure of the staircases has been augmented to ensure visitor safety.[7]

Based on a paterae block (an ornamental device) and mortice openings in the floor, uncovered during conservation works, together with documentary evidence, one room has been fitted with hammock frames. Given the evidence, it is thought this mirrors the sleeping arrangements during the convict era. The frames have a rough adzed appearance and consist of half-round architraves, skirtings and plain paterae blocks.[7]

Paint and plaster wall finishes have been incorporated into the aesthetic, including signage, which remains exposed. The removal of later false ceilings and linings in some sections has revealed earlier finishes, including the original roof structure on the second level. In others, parts of the later ceilings have been used to conceal track hangers and display partitions. Track hung spotlights and recessed down-lights have been introduced to illuminate the museum displays.[7]

Perimeter Wall and Outbuildings (Barracks Square)

The northern boundary of the Barracks site is lined with six structures of both one and two storeys. Constructed of brick, those of two storeys have had the second storey rendered in imitation of ashlar and painted off-white. In the north western corner, the original cell block remains, as does the Superintendent's Apartment midway along the boundary. In the eastern corner remnants of the original corner pavilion is visible from outside the Barracks Square. The north western corner pavilion, originally used as a cell block, has been substantially altered during its use by the District Court. Further alterations were undertaken to convert the cell block and part of the structure to the east into a cafe. Sections of the ground floor are open to visitors. A wooden platform has been constructed to allow the exposed archaeological features to be viewed. The interior walls have had various layers of paint and plaster removed in sections, so as to display the multiple renovations the interior underwent. The effect created is that of partially completed restoration - a work in progress.[7]

The Southern Perimeter is marked by a wall constructed of stone from the Gladesville Mental Hospital c.1963. It follows the northern extent of Greenway's original structure, which was demolished in 1909. The wall is also marked by the Australian Monument to the Great Irish Famine. The Monument consists of a plaque on the wall and a metal table, set with a dinner plate, protruding at a 45-degree angle from the wall. The memorial was opened by Governor-General of Australia, Sir William Deane on 28 August 1999.[7]

The Eastern Perimeter is marked by a conglomerate of three buildings, the northern two are of two storeys, while a small southern section has just one level. Central to the structures is a set of external stairs, which dominate the western facade. The stairs lead to a balcony running the length of the buildings, which provides access to the series of unconnected first floor rooms. On the ground floor, public toilets are provided in the southern section, while the remainder of the building provides office space to the Museum.[7]

The Western section consists of a wall with a central set of gates, flanked by a lodge on each side. The southern lodge was altered during the realignment of Prince Albert Road. The northern lodge is accessible by visitors, having a wooden platform to protect the exposed archaeological deposits. A fireplace is evident in the northern wall. The interior walls also display the various internal treatments, the plaster having been removed to expose the brick construction.[7]

Archaeology

Formal archaeological investigations began at the Hyde Park Barracks during the 1980s restoration work. Originally Carol Powell, who was employed to research the archival material, was also asked to catalogue artefacts exposed by the conservation works. It quickly became apparent that the magnitude and preservation of the archaeological deposits required more attention and Wendy Thorp was employed in September 1980.[7]

Thorp excavated a series of test-trenches before recommending a larger scale program was needed. Patricia Burritt completed what was known as the Stage II excavations. Trenches were located to over all aspects of the Barracks. Small scale trenches were excavated near the entrance to the Dormitory Block and in the northern perimeter buildings, formerly the bakery. A large open-area was excavated in the courtyard east of the Dormitory Block. Extensive excavations were also undertaken in the underfloor spaces between levels one and two and levels two and three. The last of these excavations exposed a remarkable artefact collection of paper and fabric, items not commonly preserved in archaeological deposits. In 2006 a publication was released by the Historic Houses Trust that interprets these artefacts.[24][7]

Concealed for up to 160 years in the cavities between floorboards and ceilings, the assemblage is a unique archaeological record of institutional confinement, especially of women. The underfloor assemblage dates to the period 1848 to 1886, during which a female Immigration Depot and a Government Asylum for Infirm and Destitute Women occupied the second and third floors of the Barracks.[2]

Since the completion of the 1980s restoration works any disturbance of the ground has been preceded by archaeological excavation, seeing a number of smaller excavations carried out for the laying of pipes etc. and the construction of the Australian Monument to the Great Irish Famine. There remains the potential for further archaeological materials to be uncovered.[7]

Museum

In 1994, Hyde Park Barracks underwent conservation and adaptation work by award-winning architects Tonkin Zulaikha Greer and conservation architects Clive Lucas Stapleton and Partners. The completed project won the Australian Institute of Architects national Lachlan Macquarie Award in 1992. Now, the newly installed Hyde Park Barracks is a museum operated by the Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales. Tourists who visit the building discover the daily lives of convicts and other occupants through exhibitions on Sydney's male convict labour force, Australia's convict system, an innovative soundscape, excavated artefacts, exposed layers of building fabric and the complex's rooms and spaces.

In June 2015, Mark Speakman, the then Minister for the Environment of New South Wales announced Unlocking Heritage, a two-year program aimed at giving children the opportunity to experience Sydney's living museums. This program will allow students to wear convict clothing and sleep in the Barrack's hammocks. A million dollars has been allocated for this program. Museum director Mark Goggin thinks that children will learn more about history if they can experience it hands-on, '"Particularly for the kids to wear the convict shirts, eat the gruel, sleep over with their mates in hammocks and imagining what life was like 200 years ago."' The program is starting out with children and hoping to expand to adult participation.[25]

Heritage listing

World Heritage List

In July 2010, at the 34th session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, the Hyde Park Barracks and ten other Australian sites with a significant association with convict transportation were inscribed as a group on the World Heritage List as the Australian Convict Sites.[26] The listing explains that the 11 sites present "the best surviving examples of large-scale convict transportation and the colonial expansion of European powers through the presence and labour of convicts". Of the 11 sites the Old Great North Road, Old Government House at Parramatta and Cockatoo Island are also within the Sydney region.

Australian National Heritage List

The site was placed on the National Heritage List on 1 August 2007. It was recognised:

- as a turning point in the management of convicts in the colony, as the government could now exercise more effective control over convicts,

- for its links with Governor Macquarie and his role in developing the colony's infrastructure, and

- as a demonstration of the skill of its architect, Francis Greenway.[27]

New South Wales State Heritage List

The primary significance of Hyde Park Barracks is its unique evidence of the convict period of Australian history, particularly in its demonstration of the accommodation and living conditions of male convicts in NSW 1819–1848. They also provide evidence of the conditions experienced by immigrant groups between 1848 and 1887. The site is important for its significant archaeological record, both excavated and unexcavated, relating to the convict and immigrant periods of occupation. The barracks is one of the finest surviving works by Francis Greenway, the essence of his design persisting through various adaptations. They provide major evidence of Governor Macquarie's vision for Sydney and the relationship with The Domain, the Mint, St James' Church and Hyde Park demonstrate patterns of early 19th century planning in NSW.[28][7]

Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney (inclusive of the Sydney Mint), was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999 having satisfied the following criteria.[7]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

There is a diversity of structures which document the evolution of the Hyde Park Barracks complex from the late Georgian era to modern times: from the era of convict cell blocks and enclosed penal institutions, through to judicial courts and offices and present-day museum. It contains two fig trees on Macquarie Street which are symbolic of a number of significant town planning schemes throughout the 19th century, such as the creation of Chancery Square, (now known as Queen's Square). Within the complex are structures associated with the first purpose-built government institution for the housing of convicts. It is associated with the development of the legal system in NSW being the location of the first meeting in 1830 of the bench of magistrates for the Court of General Sessions and the first location of the Metropolitan District Court established under the District Courts Act, 1958. It is associated with other historic landmarks in the area such as the former Rum Hospital, St James' Church, Hyde Park, the Domain, St Mary's Cathedral and Macquarie Street.[7]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

It contains elements such as the perimeter walls, parts of the two gate lodges, one former pavilion and parts of another, some external and probably internal walls on the northern range of buildings which are associated with the convict architect Francis Greenway's design. Together with the central barracks building, the place possesses a rich architectural history from the earliest days of European settlement in Australia.[29][7]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

It contains a museum which is a centre of tourist and cultural activity in Sydney.[7]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

The site contains areas of potential archaeological significance which are likely to provide significant insight into the establishment of the place and its subsequent developmental history.[30][7]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

It is the oldest example of a walled penal institution in Australia.[29] The barracks provide rare evidence of the standards and skills of building practice, architectural design and urban planning in early 19th century Sydney[7]

Operations

The Hyde Park Barracks are part of the Sydney Living Museums series. Other locations in the series are the Susannah Place Museum, the Museum of Sydney and the Justice & Police Museum.[31] A pass can be purchased at any of the locations that will enable visitors to visit all four locations at a discounted price.[32]

Gallery

Hyde Park Barracks, interior

Hyde Park Barracks, interior Irish Famine Memorial, Hyde Park Barracks by Hossein Valamanesh

Irish Famine Memorial, Hyde Park Barracks by Hossein Valamanesh Hyde Park Barracks from the Skytower

Hyde Park Barracks from the Skytower During Macquarie Night Lights (December 2006)

During Macquarie Night Lights (December 2006) Rat Curators of Hyde Park Barracks

Rat Curators of Hyde Park Barracks

See also

References

- 1 2 Chapter 1 of Australian Government's "Australian Convict Sites" World Heritage nomination Archived 17 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 5 August 2010

- 1 2 Davies, Peter; Crook, Penny; Murray, Tim (2013). An archaeology of institutional confinement : the Hyde Park Barracks, 1848-1886. Sydney: Sydney University Press. pp. xiii, xxix. ISBN 9781920899790. OCLC 858610704.

- ↑ "Stories and Histories". Sydney Living History Museums. Archived from the original on 22 August 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Australian Convict Sites". World Heritage Convention. United Nations. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Australian Convict Sites". Department of the Environment. Australian Government. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Hyde Park Barracks, Macquarie St, Sydney, NSW, Australia (Place ID 105935)". Australian Heritage Database. Australian Government. 1 August 2007. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 "Mint Building and Hyde Park Barracks Group". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00190. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - ↑ "'Work in progress': Hyde Park Barracks closes for $18 million transformation". The Sydney Morning Herald. 10 January 2019.

- ↑ Dow, Steve (20 February 2020). "'Designed to wake people up': Jonathan Jones unveils major public work at Hyde Park barracks". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ↑ ondinee (4 June 2019). "On this day: an 'excellent institution' opens". Sydney Living Museums. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- 1 2 Cumberland County Council 1962:6

- ↑ Collins 1994:19

- ↑ Crook & Murray 2006:19

- 1 2 Collins 1994:24

- ↑ Collins 2006:24

- ↑ Collins 1994:7

- ↑ Watts, 2014

- 1 2 Abrahams, 2016, 9

- ↑ Liebermann, 2016, 6-7

- 1 2 Sheedy 1978

- ↑ State Planning Authority 1965:7

- ↑ Broadbent & Hughes 1997:56-57

- ↑ Walker & Moore 1990:38

- ↑ Crooks & Murray 2006

- ↑ Donegan, John. "Sydney's Hyde Park Barracks site of student sleepover as museum receives funding injection". 702 ABC Sydney. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "UNESCO World Heritage Centre – World Heritage Committee inscribes seven cultural sites on World Heritage List". UNESCO World Heritage Centre website. United Nations. 31 July 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ↑ "Department of the Environment and Energy". Department of the Environment and Energy. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ↑ Historic Houses Trust 1990:5

- 1 2 Lucas, Stapleton & Partners 1996:73

- ↑ Lucas, Stapleton & Partners 1996:74

- ↑ "Sydney Living Museums – Hyde Park Barracks Museum". Sydney Living Museums. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Sydney Museums Pass". Sydney Living Museums. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

Bibliography

- "Hyde Park Barracks Museum". 2007.

- Abrahams, Hector (2016). The Gates of the Sydney Mint: a long (and convoluted) history.

- Attraction Homepage (2007). "Mint Building and Hyde Park Barracks Group".

- Cumberland County Council (1962). Historic Buildings: Central Area of Sydney, Volume II.

- Historic Houses Trust (2007). "Hyde Park Barracks Museum". Archived from the original on 17 July 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2006.

- Historic Houses Trust (2004). "Museums". Archived from the original on 12 February 2006. Retrieved 23 February 2006.

- Hyde Park Barracks Cafe (2007). "Hyde Park Barracks Cafe".

- Liebermann, Sophie (2016). Rum Hospital Revealed.

- Lynn Collins, ed. (1994). Hyde Park Barracks.

- Marsh, Glennda S. (1982). The Conservation of Artefacts from the Hyde Park Barracks & Mint Buildings - National Estate Grants Program 1980/81 Project No.14: archaeological artefact analysis.

- Penny Crook & Tim Murray (2006). An Archaeology of Institutional Refuge: The Material Culture of the Hyde park Barracks, Sydney, 1848-1886.

- Penny Crook & Tim Murray (2003). Assessment of Historical and Archaeological Resources of the Royal Mint Site, Sydney.

- Sydney Living Museums (2017). "Convict Sydney".

- Watts, Peter (2014). (Open) Letter to Tim Duddy, Chairman, Friends of Historic Houses Trust Inc.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article contains material from Mint Building and Hyde Park Barracks Group, entry number 190 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

This Wikipedia article contains material from Mint Building and Hyde Park Barracks Group, entry number 190 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

External links

- Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney Living Museums

- A Place For The Friendless Female: Sydney's Female Immigration Depot (online version of the Hyde Park Barracks Museum exhibition by the same name)

- Tonkin Zulaikha Greer (Website)

- UNESCO announcement of World Heritage listing

- Laila Ellmoos (2008). "Hyde Park Barracks". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Retrieved 11 October 2015.[CC-By-SA]

- Perry McIntyre – Global Irish Studies Centre, University of New South Wales (2012). "Irish Famine Memorial, Hyde Park Barracks". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 8 October 2015. [CC-By-SA]

- Colonial Secretary's papers 1822-1877, State Library of Queensland- includes digitised letters written about Hyde Park Barracks to the Colonial Secretary of New South Wales. Reel 8 Item 2347 includes list of prisoners forwarded from the Hydpe Park Barracks to various penal settlements in Australia.