For India, the concept of non-alignment began as a policy of non-participation in the military affairs of a bipolar world and in the context of colonialism aimed towards optimum involvement through multi-polar participation towards peace and security. It meant a country should be able to preserve a certain amount of freedom of action internationally. There was no set definition of non-alignment, which meant the term was interpreted differently by different politicians and governments, and varied in different contexts.[1] The overall aims and principles found consensus among the movement members.[2] Non-aligned countries, however, rarely attained the freedom of judgement they desired and their actual behaviour towards the movement's objectives, such as social justice and human rights, were unfulfilled in many cases. India's actions often resembled those of aligned countries.[3] The response of the non-aligned nations during India's wars in 1962, 1965 and 1971 revealed non-aligned positions on issues such as secession.[4] The non-aligned nations were unable to fulfil the role of peacekeepers during the Indo-China war of 1962 and the Indo-Pakistan war of 1965 despite meaningful attempts.[5] The non-aligned response to the Bangladesh Liberation War and the following 1971 Indo-Pakistan War showed most of the non-aligned nations prioritised territorial integrity above human rights, which could be explained by the recently attained statehood for the non-aligned.[6] During this period, India's non-aligned stance was questioned and criticized.[7] Jawaharlal Nehru had not wanted the formalization of non-alignment and none of the non-aligned nations had commitments to help each other.[8] The international rise of countries such as China also decreased incentives for the non-aligned countries to stand in solidarity with India.[9]

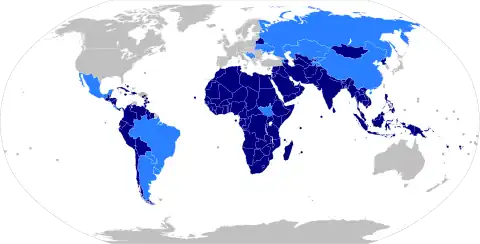

India played an important role in the multilateral movements of colonies and newly independent countries that wanted to participate in the Non-Aligned Movement. The country's place in national diplomacy, its significant size and its economic growth turned India into one of the leaders of the Non-Aligned Movement.[10]

Origin of non-alignment in India

| Timeline |

|---|

|

Prior to Independence and India becoming a republic, Jawaharlal Nehru contemplated the path the country would take in world affairs.[15] In 1946, Nehru, as a part of the cabinet of the Interim Government of India, said during a radio broadcast; "we propose, as far as possible, to keep away from the power politics of groups, aligned against one another, which have led in the past to world wars and which may again lead to disasters on an even vaster scale".[16] In 1948, he made a speech to the Constituent Assembly (Legislative) titled "We Lead Ourselves" in which he said the world was going through a phase in which the foreign policies of major powers had "miserably failed".[17] In the speech, he talked about what alignment entailed, saying:

What does joining a bloc mean? After all it can only mean one thing: give up your view about a particular question, adopt the other party's view on that question in order to please it […] Our instructions to our delegates have always been first to consider each question in terms of India's interest, secondly, on its merit - I mean to say if it did not affect India, naturally on its merits and not merely to do something or to give a vote just to please this power or that power ...[18]

In 1949, he told the Assembly:

We have stated repeatedly that our foreign policy is one of keeping aloof from the big blocs [….] being friendly to all countries... not becoming entangled in any alliances… that may drag us into any possible conflict. That does not, on the other hand, involve any lack of close relationships with other countries.[19]

Some saw confusion in these speeches and the West questioned Nehru's "neutrality";[20] in the United States in 1949, Nehru said; "we are not blind to reality nor do we acquiesce in any challenge to man's freedom from whatever quarters it may come. Where freedom is menaced or justice threatened or where aggression take place, we cannot and shall not be neutral".[20] The term 'Non-Alignment' was used for the first time in 1950 at the United Nations when both India and Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia rejected alignment with any side in the Korean War.[21] Over the years, Nehru made a number of comments on non-alignment; in 1957 he said, "Non-alignment seems to me as the natural consequence of an independent nation functioning according to its own rights. After all alignment means being regimented to do something you do not like and thereby giving up certain measures of independent judgement and thinking."[22]

Indian non-alignment was a product of the Cold War, a bipolar world[23] and India's colonial experience and the non-violent Indian independence struggle. According to Rejaul Karim Laskar, the Non-Aligned Movement was devised by Nehru and other leaders of newly independent countries of the Third World to "guard" their independence "in face of complex international situation demanding allegiance to either of the two warring superpowers".[24]

The term "non-alignment" was coined by V K Menon in his speech at the United Nations (UN) in 1953,[25] which was later used by Indian Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru during his speech in 1954 in Colombo, Sri Lanka, in which he described the Panchsheel (five restraints) to be used as a guide for Sino-Indian relations, which were first put forth by Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai. These principles would later become the basis of the Non-Aligned Movement. The five principles were: mutual respect for each other's territorial integrity and sovereignty; mutual non-aggression; mutual non-interference in domestic affairs; equality and mutual benefit; and peaceful co-existence. Nehru's concept of non-alignment brought India considerable international prestige among newly independent states that shared its concerns about the military confrontation between the superpowers and the influence of the former colonial powers. By laying the foundation stone of 'Non-Alignment Movement', India was able to establish a significant role for itself as a leader of the newly independent world and in the multilateral organisations like the UN.

According to Jairam Ramesh, neither Menon or Nehru "particularly cared for or were fond of the term 'non alignment' much less of the idea of 'non-aligned movement' or a 'non aligned grouping'".[25]

Early developments

The Non-Aligned Movement had its origins in the 1947 Asian Relations Meeting in New Delhi and the 1955 Asian-African Conference in Bandung, Indonesia. India also participated in the 1961 Belgrade Conference that officially established the Non-Aligned Movement but Nehru's declining prestige limited his influence. In the 1960s and 1970s, India concentrated on internal problems and bilateral relations but retained membership in the increasingly factionalised and radicalised movement. During the contentious 1979 Havana summit, India worked with moderate nations to reject Cuban President Fidel Castro's proposition that "socialism" was the "natural ally" of non-alignment.

Non-aligned response to Sino-Indian conflict

The Sino-India war of 1962 was one of the first situations in which the non-aligned countries faced a situation that was not directly related to the two blocs or issues such as colonialism.[26] The Belgrade Summit had been held in 1961 with representation from 24 countries, the reaction of which ranged from ignoring the situation, making low-profile appeals and statements to making attempts to mediate.[27]

According to V.K. Krishna Menon in 1964; "non-aligned nation(s) must be non-aligned with the non-aligned ... that is why, when some people here say, 'why haven't the non-aligned people stood up and shouted against China', I tell them, 'they have their own policy, they have their own independence'".[28] In 1984, Sarvepalli Gopal said; "India ... found non-alignment deteriorating into isolation. Even the other non-aligned leaders, with the honourable exception of Nasser and Tito were guarded in their response to India's case.[28]

Non-alignment and Indo-Pakistan conflicts

The response of non-aligned nations to the Indo-Pakistan conflicts revealed insights into their views towards self determination, issues of secession, the use of force in boundary disputes, armed intervention, external support in liberation struggles, human rights and genocide.[29][30] Many of the non-aligned nations were facing similar problems in their own countries.[30] The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 saw a continuing decline in the role of non-aligned nations in peacekeeping, a decline that started with a failure to mediate during the 1962 Indo-Sino war.[5]

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 started as an "internal issue" of human rights in Pakistan, an issue of human rights but became India's problem with the migration of millions of refugees into India, which was referred to as "civilian aggression".[31] Two major alignments developed; Pakistan aligned with the United States and China, and India aligned with the Soviet Union.[32] Without Soviet support, India would not have been able to defend itself against the US-Pakistan-China alliance.[32] This polarization influenced all forums and international opinion, including that of the Non-Aligned Movement, which at the time consisted of 53 nations.[32] The non-aligned responses varied from calling the situation an internal matter of Pakistan to seeking a political solution to a humanitarian problem but only one of the non-aligned states mentioned the human rights aspect.[33] It took time for some of the non-aligned nations to deal with the emergence of Bangladesh and to appreciate the contradictory issues of Pakistan national unity and the Bengali right to self-determination.[34] During the Uniting for Peace resolution, non-aligned responses became clearer; some of the African non-aligned nations were the most critical of India while others that wanted to stay neutral made contradictory statements. The predicament of small non-aligned states was also seen.[35] India was disappointed with the non-aligned response. In August 1971, M. C. Chagla, a former foreign affairs minister of India, said:

Look at the non-aligned countries, we have prided ourselves of our nonalignment. What have the non-aligned countries done? Nothing. ... many countries have skeletons in their cupboard. They have minorities whom they have not treated well and they feel that if they support Bangladesh, these minorities will also rise in revolt, in rebellion, against the oppressive policies being pursued by the administration.[36][37]

The signing of the Indo-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation in 1971 and India's involvement in the internal affairs of its smaller neighbours in the 1970s and 1980s tarnished its image as a non-aligned nation and led some observers to question India's non-alignment.[7] Rather than an issue of non-aligned solidarity, India's declining influence in non-aligned areas compared to the rise of China also affected the international withdrawal of support to India.[9] There was no commitment for the non-aligned nations to help each other.[38] Non-alignment also affected India's bilateral relations with many countries.[38]

21st century

In 2019, India was represented at the 18th NAM summit by its vice president and external affairs minister.[13] In May 2020, the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi participated in a NAM virtual summit.[14] In July 2020, India's External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar said during an interview; "non-alignment was a term of a particular era and a particular, shall I say, geopolitical landscape".[39][40][41]

See also

Notes

- ↑ In 1979 the Havana Declaration was adopted to clarify the purpose of NAM: "the national independence, sovereignty, territorial integrity and security of non-aligned countries" in their "struggle against imperialism, colonialism, neo-colonialism, racism, and all forms of foreign aggression, occupation, domination, interference or hegemony as well as against great power and bloc politics."[12]

References

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 9, Chapter 1.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 5, Chapter 1.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 315–320, Chapter 6.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 301–302, Chapter 6.

- 1 2 Upadhyaya 1987, p. 233, Chapter 4.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 295, Chapter 5.

- 1 2 Upadhyaya 1987, p. 298, Chapter 5.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 302–303, Chapter 6.

- 1 2 Upadhyaya 1987, p. 301–304, Chapter 6.

- ↑ Pekkanen, Saadia M.; Ravenhill, John; Foot, Rosemary, eds. (2014). Oxford Handbook of the International Relations of Asia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-19-991624-5.

- 1 2 3 Upadhyaya 1987, p. 2.

- ↑ White, Nigel D. (24 October 2014). The Cuban Embargo under International Law: El Bloqueo. Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-134-45117-3.

- 1 2 "Naidu, Jaishankar meet Afghan President on Non alignment movement (NAM) Summit sidelines". ANI News. 26 October 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- 1 2 Nagda, Ashutosh (11 May 2020). "India's Renewed Embrace of the Non-Aligned Movement". The Diplomat. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ↑ Grover 1992, p. 142, 151.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 2, Chapter 1.

- ↑ Grover 1992, p. 142, 147, Chapter 1.

- ↑ Grover 1992, p. 147, 150, Chapter 1.

- ↑ Grover 1992, p. 151, Chapter 1.

- 1 2 Chary 1995, p. 59–60.

- ↑ Ivo Goldstein; Slavko Goldstein (2020). Tito [Tito] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Profil. pp. 636–647. ISBN 978-953-313-750-6.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 13.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 11, Chapter 1.

- ↑ Laskar, Rejaul Karim. "Respite from Disgraceful NDA Foreign Policy". Congress Sandesh. 6 (10): 8.

- 1 2 Ramesh, Jairam (19 December 2019). "Part 1 Chapter 2". A Chequered Brilliance: The Many Lives of V.K. Krishna Menon. Penguin Random House India Private Limited. ISBN 978-93-5305-740-4.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 47-48, Chapter 2.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 66-76, Chapter 2.

- 1 2 Upadhyaya 1987, p. 47, Chapter 2.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 168, Chapter 4.

- 1 2 Upadhyaya 1987, p. 235, Chapter 5.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 251, Chapter 5.

- 1 2 3 Upadhyaya 1987, p. 255, Chapter 5.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 264-270, Chapter 5.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 272, Chapter 5.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 272–275, Chapter 5.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1987, p. 290, Chapter 5.

- ↑ Ghaṭāṭe, Narayana Madhava, ed. (1971). Bangla Desh: Crisis & Consequences: Proceedings of the Seminar, 7th and 8th August 1971. Deendayal Research Institute; [distributors: Indian Publishing House, Delhi]. pp. 83, 84.

- 1 2 Upadhyaya 1987, p. 302–304, Chapter 6.

- ↑ Bhaumik, Anirban (20 July 2020). "S Jaishankar says era of non-alignment gone, as US, Indian warships conduct joint drills". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ↑ "EAM's interaction on Mindmine Mondays, CNBC (July 21, 2020)". Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. 30 July 2020. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ↑ Pant, Harsh V. "Gradually burying non-alignment". ORF. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

Sources

- Upadhyaya, Priyankar (1987). Non-aligned States And India's International Conflicts (Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Jawaharlal Nehru University thesis). Centre For International Politics Organization And Disarmament School Of International Studies New Delhi. hdl:10603/16265.

- Grover, Verinder, ed. (1992). Uno, Nam, Nieo, Saarc and India's Foreign Policy. Vol. 10 of International relations and foreign policy of India. New Delhi: Deep and Deep Publications. ISBN 9788171003495.

- Chary, M. Srinivas (1995). The Eagle and the Peacock: U.S. Foreign Policy Toward India Since Independence. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313276026.

Further reading

- Gupta, Devender Kumar (1987). Role of India in Non-Aligned Movement: A Select Annotated Bibliography (submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of the degree of Master of Library Science) (PDF). Aligarh: Department Of Library Science, Aligarh Muslim University.

- Chaudhuri, Rudra. Forged in Crisis: India and the United States since 1947. Oxford University Press, 2014.

- "Library of Congress: Federal Research Division Country Profile: India, September 1995". Library of Congress Country Studies (All works are released in Public domain). Retrieved 6 November 2007.