| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | RU-38882; RU-882; 2,5-Seco-A-dinorestr-9-en-17β-ol-5-one 17β-acetate |

| Drug class | Nonsteroidal antiandrogen |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

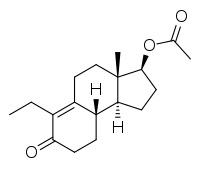

| Formula | C18H26O3 |

| Molar mass | 290.403 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Inocoterone acetate (USAN) (developmental code names RU-38882, RU-882) is a steroid-like nonsteroidal antiandrogen (NSAA) that was developed for topical administration to treat acne but was never marketed.[1][2] It is the acetate ester of inocoterone, which is less potent in comparison.[3] Inocoterone acetate is actually not a silent antagonist of the androgen receptor but rather a weak partial agonist, similarly to steroidal antiandrogens like cyproterone acetate.[4]

Inocoterone acetate was investigated for the treatment of acne but showed only modest (albeit statistically significant) efficacy in clinical trials.[2][5][6] A reduction of 26% of lesions was observed in males treated with the drug after 16 weeks (~3.7 months).[6][1] However, this is notably far less than that achieved with other agents such as benzoyl peroxide or antibiotics, which produce 50–75% reductions within 2 months.[1] Similar poor results with the topical route have disappointingly been found for other antiandrogens, such as cyproterone acetate and spironolactone.[1] Similarly to rosterolone, inocoterone acetate has no systemic antiandrogenic activity when applied systemically.[7]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Boettger RF, Fukushima LH (2006). "Common skin disorders". In Helms RA, Quan DJ (eds.). Textbook of Therapeutics: Drug and Disease Management. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 203–256 (211). ISBN 978-0-7817-5734-8.

- 1 2 Diamanti-Kandarakis E (September 1999). "Current aspects of antiandrogen therapy in women". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 5 (9): 707–23. doi:10.1002/chin.200002286. PMID 10495361. S2CID 20224641.

- ↑ Venuti MC (January 1987). "Dermatological agents". Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry. Academic Press. 22: 201-212 (203). doi:10.1016/S0065-7743(08)61168-9. ISBN 978-0-08-058366-2.

- ↑ Térouanne B, Tahiri B, Georget V, Belon C, Poujol N, Avances C, et al. (February 2000). "A stable prostatic bioluminescent cell line to investigate androgen and antiandrogen effects". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 160 (1–2): 39–49. doi:10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00251-8. PMID 10715537. S2CID 13737435.

- ↑ Kim GE, Kimball AB (25 June 2015). "Androgen effects on the skin". In Plouffe Jr L, Rizk BR (eds.). Androgens in Gynecological Practice. Cambridge University Press. pp. 79–88 (84). doi:10.1017/CBO9781139649520.010. ISBN 978-1-316-29887-9.

- 1 2 Lookingbill DP, Abrams BB, Ellis CN, Jegasothy BV, Lucky AW, Ortiz-Ferrer LC, et al. (September 1992). "Inocoterone and acne. The effect of a topical antiandrogen: results of a multicenter clinical trial". Archives of Dermatology. 128 (9): 1197–1200. doi:10.1001/archderm.128.9.1197. PMID 1387778.

- ↑ Neumann F, Töpert M (1990). "Antiandrogens and Hair Growth: Basic Concepts and Experimental Research". In Orfanos CE, Happle R (eds.). Hair and Hair Diseases. pp. 791–826. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-74612-3_34. ISBN 978-3-642-74614-7.