Japanese painting (絵画, kaiga; also gadō 画道) is one of the oldest and most highly refined of the Japanese visual arts, encompassing a wide variety of genres and styles. As with the history of Japanese arts in general, the long history of Japanese painting exhibits synthesis and competition between native Japanese aesthetics and the adaptation of imported ideas, mainly from Chinese painting, which was especially influential at a number of points; significant Western influence only comes from the 19th century onwards, beginning at the same time as Japanese art was influencing that of the West.

Areas of subject matter where Chinese influence has been repeatedly significant include Buddhist religious painting, ink-wash painting of landscapes in the Chinese literati painting tradition, calligraphy of sinograms,[1] and the painting of animals and plants, especially birds and flowers. However, distinctively Japanese traditions have developed in all these fields. The subject matter that is widely regarded as most characteristic of Japanese painting, and later printmaking, is the depiction of scenes from everyday life and narrative scenes that are often crowded with figures and detail. This tradition no doubt began in the early medieval period under Chinese influence that is now beyond tracing except in the most general terms, but from the period of the earliest surviving works had developed into a specifically Japanese tradition that lasted until the modern period.

The official List of National Treasures of Japan (paintings) includes 162 works or sets of works from the 8th to the 19th century that represent peaks of achievement, or very rare survivals from early periods.

Timeline

Ancient Japan and Asuka period (until 710)

The origins of painting in Japan date well back into Japan's prehistoric period. Simple figural representations, as well as botanical, architectural, and geometric designs are found on Jōmon period pottery and Yayoi period (1000 BC – 300 AD) dōtaku bronze bells. Mural paintings with both geometric and figural designs have been found in numerous tumuli dating to the Kofun period and Asuka period (300–700 AD).

Along with the introduction of the Chinese writing system (kanji), Chinese modes of governmental administration, and Buddhism in the Asuka period, many art works were imported into Japan from China and local copies in similar styles began to be produced.

Nara period (710–794)

With further establishment of Buddhism in 6th- and 7th-century Japan, religious painting flourished and was used to adorn numerous temples erected by the aristocracy. However, Nara-period Japan is recognized more for important contributions in the art of sculpture than painting.

The earliest surviving paintings from this period include the murals on the interior walls of the Kondō (金堂) at the temple Hōryū-ji in Ikaruga, Nara Prefecture. These mural paintings, as well as painted images on the important Tamamushi Shrine include narratives such as jataka, episodes from the life of the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, in addition to iconic images of buddhas, bodhisattvas, and various minor deities. The style is reminiscent of Chinese painting from the Sui dynasty or the late Sixteen Kingdoms period. However, by the mid-Nara period, paintings in the style of the Tang dynasty became very popular. These also include the wall murals in the Takamatsuzuka Tomb, dating from around 700 AD. This style evolved into the Kara-e genre, which remained popular through the early Heian period.

As most of the paintings in the Nara period are religious in nature, the vast majority are by anonymous artists. A large collection of Nara period art, Japanese as well as from the Chinese Tang dynasty[2] is preserved at the Shōsō-in, an 8th-century repository formerly owned by Tōdai-ji and currently administered by the Imperial Household Agency.

Heian period (794–1185)

With the development of the Esoteric Buddhist sects of Shingon and Tendai, painting of the 8th and 9th centuries is characterized by religious imagery, most notably painted mandala (曼荼羅, mandara). Numerous versions of mandala, most famously the Diamond Realm Mandala and Womb Realm Mandala at Tōji in Kyoto, were created as hanging scrolls, and also as murals on the walls of temples. A noted early example is at the five-story pagoda of Daigo-ji, a temple south of Kyoto.

The Kose School was a family of court artists founded by Kanaoka Kose in the latter half of the 9th century, during the early Heian period. This school does not represent a single style of painting like other schools, but the various painting styles created by Kanaoka Kose and his descendants and pupils. This school changed Chinese style paintings with Chinese themes into Japanese style and played a major role in the formation of yamato-e painting style.[3][4]

With the rising importance of Pure Land sects of Japanese Buddhism in the 10th century, new image-types were developed to satisfy the devotional needs of these sects. These include raigōzu (来迎図), which depict Amida Buddha along with attendant bodhisattvas Kannon and Seishi arriving to welcome the souls of the faithful departed to Amida's Western Paradise. A noted early example dating from 1053 are painted on the interior of the Phoenix Hall of the Byōdō-in, a temple in Uji, Kyoto. This is also considered an early example of so-called yamato-e (大和絵, "Japanese-style painting"), insofar as it includes landscape elements such as soft rolling hills that seem to reflect something of the actual appearance of the landscape of western Japan.

The mid-Heian period is seen as the golden age of Yamato-e, which were initially used primarily for sliding doors (fusuma) and folding screens (byōbu). However, new painting formats also came to the fore, especially towards the end of the Heian period, including emakimono, or long illustrated handscrolls. Varieties of emakimono encompass illustrated novels, such as the Genji Monogatari, historical works, such as the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba, and religious works. In some cases, emaki artists employed pictorial narrative conventions that had been used in Buddhist art since ancient times, while at other times they devised new narrative modes that are believed to convey visually the emotional content of the underlying narrative. Genji Monogatari is organized into discrete episodes, whereas the more lively Ban Dainagon Ekotoba uses a continuous narrative mode in order to emphasize the narrative's forward motion. These two emaki differ stylistically as well, with the rapid brush strokes and light coloring of Ban Dainagon contrasting starkly to the abstracted forms and vibrant mineral pigments of the Genji scrolls. The Siege of the Sanjō Palace is another famous example of this type of painting.

E-maki also serve as some of the earliest and greatest examples of the onna-e ("women's pictures") and otoko-e ("men's pictures") and styles of painting. There are many fine differences in the two styles. Although the terms seem to suggest the aesthetic preferences of each gender, historians of Japanese art have long debated the actual meaning of these terms, and they remain unclear. Perhaps most easily noticeable are the differences in subject matter. Onna-e, epitomized by the Tale of Genji handscroll, typically deals with court life and courtly romance while otoko-e, often deal with historical or semi-legendary events, particularly battles.

Kamakura period (1185–1333)

These genres continued on through Kamakura period Japan. This style of art was greatly exemplified in the painting titled Night Attack on the Sanjo Palace, a piece full of vibrant colors, details, and a great visualization from a novel titled the Heiji Monogatari. E-maki of various kinds continued to be produced; however, the Kamakura period was much more strongly characterized by the art of sculpture, rather than painting. "The Kamakura period extended from the end of the twelfth through the fourteenth century. It was a time of art works, such as paintings, but mainly sculptures that brought a more realistic visual of life and its aspects at the time. In each of these statues many life-like traits were incorporated into the production of making them. Many sculptures included noses, eyes, individual fingers, and other details that were new to the sculpture place in art."

As most of the paintings in the Heian and Kamakura periods are religious in nature, the vast majority are by anonymous artists. One artist known for his perfection in this new Kamakura period art style was Unkei, and he eventually mastered this sculpturing art form and opened his own school called Kei School. As this era went on, "there were the revival of still earlier classical styles, the importation of new styles from the Continent and, in the second half of the period, the development of unique Eastern Japanese styles centering around the Kamakura era".

Muromachi period (1333–1573)

During the 14th century, the development of the great Zen monasteries in Kamakura and Kyoto had a major impact on the visual arts. Suibokuga, an austere monochrome style of ink painting introduced from the Ming dynasty China of the Song and Yuan ink wash styles, especially Muqi (牧谿), largely replaced the polychrome scroll paintings of the early zen art in Japan attached to Buddhist iconography norms from centuries earlier such as Takuma Eiga (宅磨栄賀). Despite the new chinese cultural wave generated by the Higashiyama culture, some polychrome portraiture remained – primary in the form of chinso paintings of Zen monks.[5]

Catching a Catfish with a Gourd (located at Taizō-in, Myōshin-ji, Kyoto), by the priest-painter Josetsu, marks a turning point in Muromachi painting. In the foreground a man is depicted on the bank of a stream holding a small gourd and looking at a large slithery catfish. Mist fills the middle ground, and the background, mountains appear to be far in the distance. It is generally assumed that the "new style" of the painting, executed about 1413, refers to a more Chinese sense of deep space within the picture plane.

By the end of the 14th century, monochrome landscape paintings (山水画 sansuiga) had found patronage by the ruling Ashikaga family and was the preferred genre among Zen painters, gradually evolving from its Chinese roots to a more Japanese style. A further development of landscape painting was the poem picture scroll, known as shigajiku.

The foremost artists of the Muromachi period are the priest-painters Shūbun and Sesshū. Shūbun, a monk at the Kyoto temple of Shōkoku-ji, created in the painting Reading in a Bamboo Grove (1446) a realistic landscape with deep recession into space. Sesshū, unlike most artists of the period, was able to journey to China and study Chinese painting at its source. Landscape of the Four Seasons (Sansui Chokan; c. 1486) is one of Sesshu's most accomplished works, depicting a continuing landscape through the four seasons.

In the late Muromachi period, ink painting had migrated out of the Zen monasteries into the art world in general, as artists from the Kanō school and the Ami school (ja:阿弥派) adopted the style and themes, but introducing a more plastic and decorative effect that would continue into modern times.

Important artists in the Muromachi period Japan include:

- Mokkei (c. 1250)

- Mokuan Reien (died 1345)

- Kaō Ninga (e. 14th century)

- Mincho (1352–1431)

- Josetsu (1405–1423)

- Tenshō Shūbun (died 1460)

- Sesshū Tōyō (1420–1506)

- Kanō Masanobu (1434–1530)

- Kanō Motonobu (1476–1559)

Azuchi–Momoyama period (1573–1615)

_-_left_screen.jpg.webp)

_-_right_hand_screen.jpg.webp)

In sharp contrast to the previous Muromachi period, the Azuchi–Momoyama period was characterized by a grandiose polychrome style, with extensive use of gold and silver foil that would be[6] applied to paintings, garments, architecture, etc.; and by works on a very large scale.[6] In contrast to the lavish style many knew, military elite supported rustic simplicity, especially in the form of the[7] tea ceremony where the would use weathered and imperfect utensils in a similar setting. This period began the unification of "warring" leaders under a central government. The initial dating for this period is often believed to be 1568 when Nobunaga entered Kyoto or 1573 when the last Ashikaga Shogun was removed from Kyoto. The Kanō school, patronized by Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Tokugawa Ieyasu, and their followers, gained tremendously in size and prestige. Kanō Eitoku developed a formula for the creation of monumental landscapes on the sliding doors enclosing a room. These huge screens and wall paintings were commissioned to decorate the castles and palaces of the military nobility. Most notably, Nobunaga had a massive castle built between 1576 and 1579 which proved to be one of the biggest artistic challenges for Kanō Eitoku. His successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, also constructed several castles during this period. These castles were some of the most important artistic works when it came to experimentation in this period. These castles represent the power and confidence of leaders and warriors in the new age.[8] This status continued into the subsequent Edo period, as the Tokugawa bakufu continued to promote the works of the Kanō school as the officially sanctioned art for the shōgun, daimyōs, and Imperial court.

However, non-Kano school artists and currents existed and developed during the Azuchi–Momoyama period as well, adapting Chinese themes to Japanese materials and aesthetics. One important group was the Tosa school, which developed primarily out of the yamato-e tradition, and which was known mostly for small scale works and illustrations of literary classics in book or emaki format.

Important artists in the Azuchi-Momoyama period include:

- Kanō Eitoku (1543–1590)

- Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539–1610)

- Kaihō Yūshō (1533–1615)

Edo period (1603–1868)

.jpg.webp)

The economic development that accompanied the arrival of a peaceful society in the Edo period led to the development of a wide variety of art forms, and many paintings were produced in a style different from that of the Kano and Tosa schools, which had been the orthodox school of painting. In 1970, Nobuo Tsuji (ja) published a book entitled Kisō no Keifu (奇想の系譜, Lineage of Eccentrics), which focused on painters of the "Lineage of Eccentrics" who broke with tradition, such as Iwasa Matabei, Kanō Sansetsu, Itō Jakuchū, Soga Shōhaku, Nagasawa Rosetsu, and Utagawa Kuniyoshi. This work has revolutionized the way Japanese art history is viewed, and Edo period painting has become one of the most popular areas of Japanese art in Japan. In recent years, scholars and art exhibitions have often added Hakuin Ekaku and Suzuki Kiitsu to the six artists listed by Tsuji, calling them the painters of the "Lineage of Eccentrics".[9][10][11]

One very significant school which arose in the early Edo period was the Rinpa school, which used classical themes, but presented them in a bold, and lavishly decorative format. Sōtatsu in particular evolved a decorative style by re-creating themes from classical literature, using brilliantly colored figures and motifs from the natural world set against gold-leaf backgrounds. A century later, Korin reworked Sōtatsu's style and created visually gorgeous works uniquely his own.

Another important genre which began during Azuchi–Momoyama period, but which reached its full development during the early Edo period was Nanban art, both in the depiction of exotic foreigners and in the use of the exotic foreigner style in painting. This genre was centered around the port of Nagasaki, which after the start of the national seclusion policy of the Tokugawa shogunate was the only Japanese port left open to foreign trade, and was thus the conduit by which Chinese and European artistic influences came to Japan. Paintings in this genre include Nagasaki school paintings, and also the Maruyama-Shijo school, which combine Western influences with traditional Japanese elements.

A third important trend in the Edo period was the rise of the Bunjinga (literati painting) genre, also known as the Nanga school (Southern Painting school). This genre started as an imitation of the works of Chinese scholar-amateur painters of the Yuan dynasty, whose works and techniques came to Japan in the mid-18th century. Master Kuwayama Gyokushū was the greatest supporter of creating the bunjin style. He theorised that polychromatic landscapes were to be considered at the same level of monochromatic paintings by Chinese literati.[12] Later bunjinga artists considerably modified both the techniques and the subject matter of this genre to create a blending of Japanese and Chinese styles. The exemplars of this style are Ike no Taiga, Uragami Gyokudō, Yosa Buson, Tanomura Chikuden, Tani Bunchō, and Yamamoto Baiitsu.

Nanban art by Kano Naizen, circa 1600. Important Cultural Property.

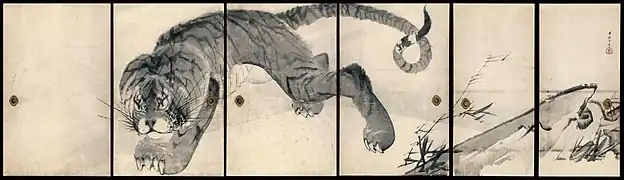

Nanban art by Kano Naizen, circa 1600. Important Cultural Property. Tiger by Nagasawa Rosetsu. Important Cultural Property.

Tiger by Nagasawa Rosetsu. Important Cultural Property.

Due to the Tokugawa shogunate's policies of fiscal and social austerity, the luxurious modes of these genre and styles were largely limited to the upper strata of society, and were unavailable, if not actually forbidden to the lower classes. The common people developed a separate type of art, the fūzokuga (風俗画, Genre art), in which painting depicting scenes from common, everyday life, especially that of the common people, kabuki theatre, prostitutes and landscapes were popular. These paintings in the 16th century gave rise to the paintings and woodcut prints of ukiyo-e.

Important artists in the Edo period include:

- Kanō Sanraku (1559–1663)

- Kanō Tan'yū (1602–1674)

- Tawaraya Sōtatsu (died 1643)

- Tosa Mitsuoki (1617–1691)

- Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716)

- Gion Nankai (1677–1751)

- Sakaki Hyakusen (1697–1752)

- Yanagisawa Kien (1704–1758)

- Yosa Buson (1716–1783)

- Itō Jakuchū (1716–1800)

- Ike no Taiga (1723–1776)

- Suzuki Harunobu (c. 1725–1770)

- Soga Shōhaku (1730–1781)

- Maruyama Ōkyo (1733–1795)

- Okada Beisanjin (1744–1820)

- Uragami Gyokudō (1745–1820)

- Matsumura Goshun (1752–1811)

- Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

- Tani Bunchō (1763–1840)

- Tanomura Chikuden (1777–1835)

- Okada Hankō (1782–1846)

- Yamamoto Baiitsu (1783–1856)

- Watanabe Kazan (1793–1841)

- Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858)

- Shibata Zeshin (1807–1891)

- Tomioka Tessai (1836–1924)

- Kumashiro Hi (Yūhi) (c. 1712–1772)

Prewar period (1868–1945)

The prewar period was marked by the division of art into competing European styles and traditional indigenous styles.

During the Meiji period, Japan underwent a tremendous political and social change in the course of the Europeanization and modernization campaign organized by the Meiji government. Western-style painting (yōga) was officially promoted by the government, who sent promising young artists abroad for studies, and who hired foreign artists to come to Japan to establish an art curriculum at Japanese schools. Kuroda Seiki is considered the leader of the yōga movement and the father of Western-style painting in Japan.[13]

However, after an initial burst of enthusiasm for western style art, the pendulum swung in the opposite direction, and led by art critic Okakura Kakuzō and educator Ernest Fenollosa, there was a revival of appreciation for traditional Japanese styles (Nihonga). In the 1880s, western style art was banned from official exhibitions and was severely criticized by critics. Hashimoto Gahō, a painter of the Kano School, was the founder of the practical side of this revival movement. He did not simply paint Japanese-style paintings using traditional techniques, but revolutionized traditional Japanese painting by incorporating the realistic expression of Yōga and set the direction for the later Nihonga movement. As the first professor at the Tokyo Fine Arts School (now Tokyo University of the Arts), he trained many painters who would later be considered Nihonga masters, including Yokoyama Taikan, Shimomura Kanzan, Hishida Shunsō, and Kawai Gyokudō.[14][15]

.jpg.webp) Right panel of the Dragon and tiger by Hashimoto Gahō. The first modern painting to be designated an Important Cultural Property.

Right panel of the Dragon and tiger by Hashimoto Gahō. The first modern painting to be designated an Important Cultural Property._L.jpg.webp) Left panel of the Parting Spring by Kawai Gyokudō. Important Cultural Property.

Left panel of the Parting Spring by Kawai Gyokudō. Important Cultural Property.

The Yōga style painters formed the Meiji Bijutsukai (Meiji Fine Arts Society) to hold its own exhibitions and to promote a renewed interest in western art.

In 1907, with the establishment of the Bunten under the aegis of the Ministry of Education, both competing groups found mutual recognition and co-existence, and even began the process towards mutual synthesis.

The Taishō period saw the predominance of Yōga over Nihonga. After long stays in Europe, many artists (including Arishima Ikuma) returned to Japan under the reign of Yoshihito, bringing with them the techniques of Impressionism and early Post-Impressionism. The works of Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne and Pierre-Auguste Renoir influenced early Taishō period paintings. However, yōga artists in the Taishō period also tended towards eclecticism, and there was a profusion of dissident artistic movements. These included the Fusain Society (Fyuzankai) which emphasized styles of post-impressionism, especially Fauvism. In 1914, the Nikakai (Second Division Society) emerged to oppose the government-sponsored Bunten Exhibition.

Japanese painting during the Taishō period was only mildly influenced by other contemporary European movements, such as neoclassicism and late post-impressionism.

However, it was resurgent Nihonga, towards mid-1920s, which adopted certain trends from post-impressionism. The second generation of Nihonga artists formed the Japan Fine Arts Academy (Nihon Bijutsuin) to compete against the government-sponsored Bunten, and although yamato-e traditions remained strong, the increasing use of western perspective, and western concepts of space and light began to blur the distinction between Nihonga and yōga.

Japanese painting in the prewar Shōwa period was largely dominated by Sōtarō Yasui and Ryūzaburō Umehara, who introduced the concepts of pure art and abstract painting to the Nihonga tradition, and thus created a more interpretative version of that genre. This trend was further developed by Leonard Foujita and the Nika Society, to encompass surrealism. To promote these trends, the Independent Art Association (Dokuritsu Bijutsu Kyokai) was formed in 1931.

During the World War II, government controls and censorship meant that only patriotic themes could be expressed. Many artists were recruited into the government propaganda effort, and critical non-emotional review of their works is only just beginning.

Important artists in the prewar period include:

- Harada Naojirō (1863–1899)

- Yamamoto Hōsui (1850–1906)

- Asai Chū (1856–1907)

- Kanō Hōgai (1828–1888)

- Hashimoto Gahō (1835–1908)

- Kuroda Seiki (1866–1924)

- Wada Eisaku (1874–1959)

- Okada Saburōsuke (1869–1939)

- Sakamoto Hanjirō (1882–1962)

- Aoki Shigeru (1882–1911)

- Fujishima Takeji (1867–1943)

- Yokoyama Taikan (1868–1958)

- Hishida Shunsō (1874–1911)

- Kawai Gyokudō (1873–1957)

- Uemura Shōen (1875–1949)

- Maeda Seison (1885–1977)

- Takeuchi Seihō (1864–1942)

- Tomioka Tessai (1837–1924)

- Shimomura Kanzan (1873–1930)

- Takeshiro Kanokogi (1874–1941)

- Imamura Shiro (1880–1916)

- Tomita Keisen (1879–1936)

- Koide Narashige (1887–1931)

- Kishida Ryūsei (1891–1929)

- Tetsugorō Yorozu (1885–1927)

- Hayami Gyoshū (1894–1935)

- Kawabata Ryūshi (1885–1966)

- Tsuchida Hakusen (1887–1936)

- Murakami Kagaku (1888–1939)

- Sōtarō Yasui (1881–1955)

- Sanzō Wada (1883–1967)

- Ryūzaburō Umehara (1888–1986)

- Yasuda Yukihiko (1884–1978)

- Kobayashi Kokei (1883–1957)

- Leonard Foujita (1886–1968)

- Yuzō Saeki (1898–1928)

- Itō Shinsui (1898–1972)

- Kaburaki Kiyokata (1878–1972)

- Takehisa Yumeji (1884–1934)

Postwar period (1945–present)

In the postwar period, the government-sponsored Japan Art Academy (Nihon Geijutsuin) was formed in 1947, containing both nihonga and yōga divisions. Government sponsorship of art exhibitions has ended, but has been replaced by private exhibitions, such as the Nitten, on an even larger scale. Although the Nitten was initially the exhibition of the Japan Art Academy, since 1958 it has been run by a separate private corporation. Participation in the Nitten has become almost a prerequisite for nomination to the Japan Art Academy, which in itself is almost an unofficial prerequisite for nomination to the Order of Culture.

.jpg.webp)

The arts of the Edo and prewar periods (1603–1945) was supported by merchants and urban people. Counter to the Edo and prewar periods, arts of the postwar period became popular. After World War II, painters, calligraphers, and printmakers flourished in the big cities, particularly Tokyo, and became preoccupied with the mechanisms of urban life, reflected in the flickering lights, neon colors, and frenetic pace of their abstractions. All the "isms" of the New York-Paris art world were fervently embraced. After the abstractions of the 1960s, the 1970s saw a return to realism strongly flavored by the "op" and "pop" art movements, embodied in the 1980s in the explosive works of Ushio Shinohara. Many such outstanding avant-garde artists worked both in Japan and abroad, winning international prizes. These artists felt that there was "nothing Japanese" about their works, and indeed they belonged to the international school. By the late 1970s, the search for Japanese qualities and a national style caused many artists to reevaluate their artistic ideology and turn away from what some felt were the empty formulas of the West. Tarō Okamoto was inspired by the pottery of the Jomon period to create many large, avant-garde paintings and sculptures for public spaces in Japan. As an artist and art theorist, he greatly enhanced the reputation of the Jomon period in Japanese art history.[16] Contemporary paintings within the modern idiom began to make conscious use of traditional Japanese art forms, devices, and ideologies. A number of mono-ha artists turned to painting to recapture traditional nuances in spatial arrangements, color harmonies, and lyricism.

Japanese-style or nihonga painting continues in a prewar fashion, updating traditional expressions while retaining their intrinsic character. Some artists within this style still paint on silk or paper with traditional colors and ink, while others used new materials, such as acrylics.

Many of the older schools of art, most notably those of the Edo and prewar periods, were still practiced. For example, the decorative naturalism of the rimpa school, characterized by brilliant, pure colors and bleeding washes, was reflected in the work of many artists of the postwar period in the 1980s art of Hikosaka Naoyoshi. The realism of Maruyama Ōkyo's school and the calligraphic and spontaneous Japanese style of the gentlemen-scholars were both widely practiced in the 1980s. Sometimes all of these schools, as well as older ones, such as the Kanō school ink traditions, were drawn on by contemporary artists in the Japanese style and in the modern idiom. Many Japanese-style painters were honored with awards and prizes as a result of renewed popular demand for Japanese-style art beginning in the 1970s. More and more, the international modern painters also drew on the Japanese schools as they turned away from Western styles in the 1980s. The tendency had been to synthesize East and West. Some artists had already leapt the gap between the two, as did the outstanding painter Shinoda Toko. Her bold sumi ink abstractions were inspired by traditional calligraphy but realized as lyrical expressions of modern abstraction.

There are also a number of contemporary painters in Japan whose work is largely inspired by anime sub-cultures and other aspects of popular and youth culture. Takashi Murakami is perhaps among the most famous and popular of these, along with and the other artists in his Kaikai Kiki studio collective. His work centers on expressing issues and concerns of postwar Japanese society through what are usually seemingly innocuous forms. He draws heavily from anime and related styles, but produces paintings and sculptures in media more traditionally associated with fine arts, intentionally blurring the lines between commercial and popular art and fine arts.

Important artists in the postwar period include:

- Ogura Yuki (1895–2000)

- Uemura Shōko (1902–2001)

- Koiso Ryōhei (1903–1988)

- Kaii Higashiyama (1908–1999)

- Tarō Okamoto (1911–1996)

See also

References

- ↑ J. Conder, Paintings and studies by Kawanabe Kyôsai, 1911, Kawanabe Kyôsai Memorial Museum, Japan: "It is sometimes said that Japanese painting is merely another kind of writing, but..." p.27

- ↑ "The Imperial Household Agency "About the Shosoin"". Shosoin.kunaicho.go.jp. Archived from the original on 2013-05-23. Retrieved 2013-04-21.

- ↑ Fenollosa, Ernest Francisco (2010). Epochs of chinese & japanese art, an outline history of east asiatic design. Place of publication not identified: Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1-176-60521-3. OCLC 944410673.

- ↑ Edmunds, Will. H (2002). Pointers and clues to the subjects of Chinese and Japanese art: as shown in drawings, prints, carvings and the decoration of porcelain and lacquer, with brief notices of the related subjects. Chicago, Ill.: Art Media Resources. ISBN 978-1-58886-001-9. OCLC 1081051954.

- ↑ Lippit, Yukio (2017). Japanese Zen buddhism and the impossible painting. Los Angeles: Getty Trust Publications. ISBN 978-1-60606-512-9. OCLC 957546034.

- 1 2 "Momoyama Period (1573–1615) | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Met.

- ↑ Willmann, Anna. "The Japanese Tea Ceremony | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Met.

- ↑ "Japanese art - Azuchi-Momoyama period | Britannica".

- ↑ "Lineage of Eccentrics: The Miraculous World of Edo Painting" (in Japanese). Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ↑ Yūji Yamashita [in Japanese] (6 March 2019). 若冲ブームのルーツはここにあり 江戸時代の絵師に迫る「奇想の系譜展」 (in Japanese). Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ↑ 美術史を変えた奇跡の1冊「奇想の系譜」は何が凄いのか?記念講演会に出て考えてみた (in Japanese). Shogakukan. 22 February 2022. Archived from the original on 20 May 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ↑ Marco, Meccarelli. 2015. "Chinese Painters in Nagasaki: Style and Artistic Contaminatio during the Tokugawa Period (1603–1868)" Ming Qing Studies 2015, Pages 175–236.

- ↑ Tanaka, Atsushi. "The Life and Arts of Kuroda Seiki". Kuroda Memorial Hall. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- ↑ Kotobank, Hashimoto Gahō. The Asahi Shimbun

- ↑ Akiko Nakano (26 May 2022). 橋本雅邦ってどんな人?人材育成にも貢献し日本画に革新をもたらしたその功績とは (in Japanese). Tokyo University of the Arts. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ↑ Masaru Sasaki. 「縄文の美」-岡本太郎とその周辺- (PDF) (in Japanese). Iwate Prefectural Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

Further reading

- Keene, Donald. Dawn to the West. Columbia University Press; (1998). ISBN 0-231-11435-4

- Mason, Penelope. History of Japanese Art . Prentice Hall (2005). ISBN 0-13-117602-1

- Paine, Robert Treat, in: Paine, R. T. & Soper A, "The Art and Architecture of Japan", Pelican History of Art, 3rd ed 1981, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), ISBN 0140561080

- Sadao, Tsuneko. Discovering the Arts of Japan: A Historical Overview. Kodansha International (2003). ISBN 4-7700-2939-X

- Schaap, Robert, A Brush with Animals, Japanese Paintings, 1700-1950, Bergeijk, Society for Japanese Arts & Hotei Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-90-70216-07-8

- Schaarschmidt Richte. Japanese Modern Art Painting From 1910 . Edition Stemmle. ISBN 3-908161-85-1

- Watson, William, The Great Japan Exhibition: Art of the Edo Period 1600-1868, 1981, Royal Academy of Arts/Weidenfeld & Nicolson

- Momoyama, Japanese art in the age of grandeur. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1975. ISBN 9780870991257.

- Murase, Miyeko (2000). Bridge of dreams: the Mary Griggs Burke collection of Japanese art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870999419.

.svg.png.webp)