| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

In Buddhism, kammaṭṭhāna is a Pali word (Sanskrit: karmasthana) which literally means place of work. Its original meaning was someone's occupation (farming, trading, cattle-tending, etc.) but this meaning has developed into several distinct but related usages all having to do with Buddhist meditation.

Etymology and meanings

| Thai Forest Tradition | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bhikkhus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sīladharās | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related Articles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Its most basic meaning is as a word for meditation, with meditation being the main occupation of Buddhist monks. In Burma, senior meditation practitioners are known as "kammatthanacariyas" (meditation masters). The Thai Forest Tradition names itself Kammaṭṭhāna Forest tradition in reference to their practice of meditating in the forests.

In the Pali literature, prior to the post-canonical Pali commentaries, the term kammaṭṭhāna comes up in only a handful of discourses and then in the context of "work" or "trade."[lower-alpha 1]

Buddhaghosa uses "kammatthana" to refer to each of his forty meditation objects listed in the third chapter of the Visuddhimagga, which are partially derived from the Pāli Canon. In this sense "kammatthana" can be understood as "occupations" in the sense of "things to occupy the mind" or "workplaces" in the sense of "places to focus the mind on during the work of meditation". Throughout his translation of the Visuddhimagga, Ñāṇamoli translates this term simply as "meditation subject".[1]

Buddhaghosa's forty meditation subjects

Kasiṇas as kammaṭṭhāna

Kasiṇa (Pali: कसिण kasiṇa; Sanskrit: कृत्स्न kṛtsna; literally, a "whole") refers to a class of basic visual objects of meditation used in Theravada Buddhism. The objects are described in the Pali Canon and summarized in the famous Visuddhimagga meditation treatise as kammaṭṭhāna on which to focus the mind whenever attention drifts.[2] Kasiṇa meditation is one of the most common types of samatha meditation, intended to settle the mind of the practitioner and create a foundation for further practices of meditation.

The Visuddhimagga concerns kasina-meditation.[3] According to American scholar monk Thanissaro Bhikkhu, "the text then tries to fit all other meditation methods into the mold of kasina practice, so that they too give rise to countersigns, but even by its own admission, breath meditation does not fit well into the mold."[3] He argues that by emphasizing kasina-meditation, the Visuddhimagga departs from the focus on jhana in the Pali Canon. Thanissaro Bhikkhu states this indicates that what "jhana means in the commentaries is something quite different from what it means in the Canon."[3]

Although practice with kasiṇas is associated with the Theravāda tradition, it appears to have been more widely known among various Buddhist schools in India at one time. Asanga makes reference to kasiṇas in the Samāhitabhūmi section of his Yogācārabhūmi.[4] Uppalavanna, one of the Buddha's chief female disciples, famously attained arahantship using a fire (tejo) kasina as her object of meditation.[5][6][7]

Of the forty objects meditated upon as kammatthana, the first ten are kasiṇa described as 'things one can behold directly'. These are described in the Visuddhimagga, and also mentioned in the Pali Tipitaka.[8] They are:

- earth (पठवी कसिण; Pali: paṭhavī kasiṇa, Sanskrit: pṛthivī kṛtsna)

- water (आपो कसिण; āpo kasiṇa, ap kṛtsna)

- fire (तेजो कसिण; tejo kasiṇa, tejas kṛtsna)

- air/wind (वायो कसिण; vāyo kasiṇa, vāyu kṛtsna)

- blue (नील कसिण; nīla kasiṇa, nīla kṛtsna)

- yellow पीत कसिण; pīta kasiṇa, pīta kṛtsna)

- red (लोहित कसिण; lohita kasiṇa, lohita kṛtsna)

- white (ओदात कसिण; odāta kasiṇa, avadāta kṛtsna)

- enclosed space, hole, aperture (आकास कसिण; ākāsa kasiṇa, ākāśa kṛtsna)

- consciousness (विञ्ञाण कसिण; viññāṇa kasiṇa, vijñāna kṛtsna) in the Pali suttas and some other texts; the bright light (of the luminous mind) (आलोक कसिण; āloka kasiṇa) according to later sources such as Buddhaghosa's Visuddhimagga.

The kasiṇas are typically described as a colored disk, with the particular color, properties, dimensions and medium often specified according to the type of kasiṇa. The earth kasiṇa, for instance, is a disk in a red-brown color formed by spreading earth or clay (or another medium producing similar color and texture) on a screen of canvas or another backing material.

Paṭikkūla-manasikāra

The next ten are impure (asubha) objects of repulsion (paṭikkūla), specifically 'cemetery contemplations' (sīvathikā-manasikāra) on ten stages of human decomposition which aim to cultivate mindfulness of body (kāyagatāsati). They are:

- a swollen corpse

- a discolored, bluish, corpse

- a festering corpse

- a fissured corpse

- a gnawed corpse

- a dismembered corpse

- a hacked and scattered corpse

- a bleeding corpse

- a worm-eaten corpse

- a skeleton

Anussati

The next ten are recollections (anussati):

- First three recollections are of the virtues of the Three Jewels:

- Next three are recollections of the virtues of:

- morality (śīla)

- liberality (cāga)

- the wholesome attributes of Devas

- The additional four recollections of:

- the body (kāya)

- death (see Upajjhatthana Sutta)

- the breath (prāna) or breathing (ānāpāna)

- peace (see Nibbana)

Brahma-vihārā

Four are 'stations of Brahma', which are the virtues of the "Brahma realm" (Pāli: Brahmaloka):

Āyatana

Four are formless states (four arūpa-āyatana):

- infinite space (Pāḷi ākāsānañcāyatana, Skt. ākāśānantyāyatana)

- infinite consciousness (Pāḷi viññāṇañcāyatana, Skt. vijñānānantyāyatana)

- infinite nothingness (Pāḷi ākiñcaññāyatana, Skt. ākiṃcanyāyatana)

- neither perception nor non-perception (Pāḷi nevasaññānāsaññāyatana, Skt. naivasaṃjñānāsaṃjñāyatana)

Others

Of the remaining five, one is of perception of disgust of food (aharepatikulasanna) and the last four are the 'four great elements' (catudhatuvavatthana): earth (pathavi), water (apo), fire (tejo), air (vayo).

Meditation subjects and the four jhānas

| Table: Rūpa jhāna | ||||

| Cetasika (mental factors) | First jhāna | Second jhāna | Third jhāna | Fourth jhāna |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kāma / Akusala dhamma (sensuality / unskillful qualities) |

secluded from; withdrawn |

does not occur | does not occur | does not occur |

| Pīti (rapture) |

seclusion-born; pervades body |

samādhi-born; pervades body |

fades away (along with distress) |

does not occur |

| Sukha (non-sensual pleasure) |

pervades physical body |

abandoned (no pleasure nor pain) | ||

| Vitakka ("applied thought") |

accompanies jhāna |

unification of awareness free from vitakka and vicāra |

does not occur | does not occur |

| Vicāra ("sustained thought") | ||||

| Upekkhāsatipārisuddhi | does not occur | internal confidence | equanimous; mindful |

purity of equanimity and mindfulness |

| Sources:[10][11][12] | ||||

According to Gunaratana, following Buddhaghosa, due to the simplicity of subject matter, all four jhanas can be induced through ānāpānasati (mindfulness of breathing) and the ten kasinas.[13]

According to Gunaratana, the following meditation subjects only lead to "access concentration" (upacara samadhi), due to their complexity: the recollection of the Buddha, dharma, sangha, morality, liberality, wholesome attributes of Devas, death, and peace; the perception of disgust of food; and the analysis of the four elements.[13]

Absorption in the first jhana can be realized by mindfulness on the ten kinds of foulness and mindfulness of the body. However, these meditations cannot go beyond the first jhana due to their involving applied thought (vitaka), which is absent from the higher jhanas.[13]

Absorption in the first three jhanas can be realized by contemplating the first three brahma-viharas. However, these meditations cannot aid in attaining the fourth jhana due to the pleasant feelings associated with them. Conversely, once the fourth jhana is induced, the fourth brahma-vihara (equanimity) arises.[13]

Meditation subjects and temperaments

Each kammatthana can be suggested, especially by a spiritual friend (kalyāṇa-mitta), to a certain individual student at some specific point, by assessing what would be best for that student's temperament and the present state of his or her mind.[14]

All of the aforementioned meditation subjects can suppress the Five Hindrances, thus allowing one to fruitfully pursue wisdom. In addition, anyone can productively apply specific meditation subjects as antidotes, such as meditating on foulness to counteract lust or on the breath to abandon discursive thought.

The Pali commentaries further provide guidelines for suggesting meditation subjects based on one's general temperament:

- Greedy: the ten foulness meditations; or, body contemplation.

- Hating: the four brahma-viharas; or, the four color kasinas.

- Deluded: mindfulness of breath.

- Faithful: the first six recollections.

- Intelligent: recollection of marana or Nibbana; the perception of disgust of food; or, the analysis of the four elements.

- Speculative: mindfulness of breath.

The six non-color kasinas and the four formless states are suitable for all temperaments.[13]

Supernormal abilities

The Visuddhimagga is one of the extremely rare texts within the enormous literature of Buddhism to give explicit details about how spiritual masters are thought to actually manifest supernormal abilities.[15] Abilities such as flying through the air, walking through solid obstructions, diving into the ground, walking on water and so forth are performed by changing one element, such as earth, into another element, such as air.[16] The individual must master kasina meditation before this is possible.[16] Dipa Ma, who trained via the Visuddhimagga, was said to demonstrate these abilities.[17]

See also

- Anussati

- Upajjhatthana Sutta (Five Remembrances)

- Ānāpānasati Sutta (Contemplation of the breath)

- Kāyagatāsati Sutta (Contemplation of the body)

- Patikkulamanasikara

- Gradual training (Patipatti)

- Buddhist meditation

- Jhana in Theravada

- Anapanasati

- Samatha

- Vipassanā

Notes

- ↑ For instance, in the first three nikayas, the term is found only in the Subha Sutta (MN 99), although there it is found 22 times. In this discourse, it is contextualized, for instance, in this question to the Buddha by the Brahmin Subha:

- "Master Gotama, the brahmins say this: 'Since the work of the household life [Pali: gharāvāsa-kammaṭṭhāna] involves a great deal of activity, great functions, great engagements, and great undertakings, it is of great fruit. Since the work of those gone forth [Pali: pabbajjā-kammaṭṭhāna] involves a small amount of activity, small functions, small engagements, and small undertakings, it is of small fruit.' What does Master Gotama say about this?"[lower-alpha 2]

- "And what does it mean to be consummate in initiative? There is the case where a lay person, by whatever occupation he makes his living [Pali: yena kammaṭṭhānena jīvikaṃ kappeti] — whether by farming or trading or cattle tending or archery or as a king's man or by any other craft — is clever and untiring at it, endowed with discrimination in its techniques, enough to arrange and carry it out. This is called being consummate in initiative."[lower-alpha 3]

- "What do you think, Sakyans. Suppose a man, by some profession or other [Pali: yena kenaci kammaṭṭhānena], without encountering an unskillful day, were to earn a half-kahapana. Would he deserve to be called a capable man, full of initiative?" [lower-alpha 6]

- Ñāṇamoli & Bodhi, 2001, p. 809; the square-bracketed Pali is from Bodhgaya News' searchable Tipitaka database at .

- Thanissaro, 1995; the square-bracketed Pali is from Bodhgaya News' searchable Tipitaka database at .

- http://bodhgayanews.net/tipitaka.php?title=sutta%20pitaka&action=next&record=6653

- http://bodhgayanews.net/tipitaka.php?title=&record=6689

- Thanissaro, 2000; the square-bracketed Pali is from Bodhgaya News' searchable Tipitaka database starting at .

References

- ↑ Buddhaghosa & Nanamoli (1999), pp. 90–91 (II, 27–28, "Development in Brief"), 110ff. (starting with III, 104, "enumeration"). It can also be found sprinkled earlier in this text as on p. 18 (I, 39, v. 2) and p. 39 (I, 107).

- ↑ Davidji (2017-03-07). Secrets of Meditation Revised Edition. Hay House, Inc. ISBN 9781401954116.

- 1 2 3 Bhikkhu Thanissaro, Concentration and Discernment Archived 2019-05-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Buddhist Insight: Essays by Alex Wayman. Motilal Banarsidass: 1984 ISBN 0-89581-041-7 pg 76

- ↑ Buswell, Robert E. Jr.; Lopez, Donald S. Jr. (2013-11-24). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. p. 945. ISBN 9781400848058.

- ↑ Therī, Tathālokā. "The Amazing Transformations of Arahant Theri Uppalavanna" (PDF). bhikkhuni.et. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-10-17. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- ↑ "03. The Story about the Elder Nun Uppalavanna". www.ancient-buddhist-texts.net. Archived from the original on 2017-07-28. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- ↑ A.v.36, A.v.46-60, M.ii.14; D.iii.268, 290; Nett.89, 112; Dhs.202; Ps.i.6, 95

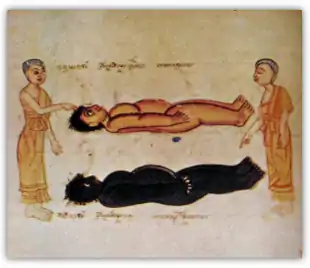

- ↑ from Teaching Dhamma by pictures: Explanation of a Siamese Traditional Buddhist Manuscript

- ↑ Bodhi, Bhikku (2005). In the Buddha's Words. Somerville: Wisdom Publications. pp. 296–8 (SN 28:1-9). ISBN 978-0-86171-491-9.

- ↑ "Suttantapiñake Aïguttaranikàyo § 5.1.3.8". MettaNet-Lanka (in Pali). Archived from the original on 2007-11-05. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ↑ Bhikku, Thanissaro (1997). "Samadhanga Sutta: The Factors of Concentration (AN 5.28)". Access to Insight. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gunaratana (1988).

- ↑ See, e.g., Buddhaghosa & Nanamoli (1999), p. 90, which states: "He should approach the good friend, the giver of a meditation subject, and he should apprehend from among the forty meditation subjects one that suits his own temperament."

- ↑ Jacobsen, Knut A., ed. (2011). Yoga Powers. Leiden: Brill. p. 93. ISBN 9789004212145.

- 1 2 Jacobsen, Knut A., ed. (2011). Yoga Powers. Leiden: Brill. pp. 83–86. ISBN 9789004212145.

- ↑ Schmidt, Amy (2005). Dipa Ma. Windhorse Publications Ltd. p. Chapter 9 "At Home in Strange Realms".

Further reading

- Buddhaghosa, Bhadantacariya & Bhikkhu Nanamoli (trans.) (1999), The Path of Purification: Visuddhimagga. Seattle: BPS Pariyatti Editions. ISBN 1-928706-00-2.

- Gunaratana, Henepola (1988). The Jhanas in Theravada Buddhist Meditation (Wheel No. 351/353). Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 955-24-0035-X. Retrieved from "Access to Insight" at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/gunaratana/wheel351.html.

- Ñāṇamoli, Bhikkhu (trans.) & Bodhi, Bhikkhu (ed.) (2001). The Middle-Length Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Majjhima Nikāya. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-072-X.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1995), Dighajanu (Vyagghapajja) Sutta: To Dighajanu (AN 8.54). Retrieved 6 Apr. 2010 from "Access to Insight" at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an08/an08.054.than.html.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (2000), Sakka Sutta: To the Sakyans (on the Uposatha) (AN 10.46). Retrieved 6 Apr. 2010 from "Access to Insight" at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an10/an10.046.than.html.

External links

- In search of a teacher by Dr. Tin Htut

- Samatha and vipassana by Sayadaw U Uttamasara

- Reaching Nibbana through insight a guide by Ven. K. Nyanananda

- The Forty Meditation Objects: Who Should Use Which? by Karen Andrews

- Dharmathai Kammathana Blog Chinawangso Bhikkhu

- "Colour-Kasiṇa Meditation," by Thitapu Bhikkhu, includes instructions for use and construction of the kasiṇa object. Via Archive.org.

- "Kasiṇa: The use of a Visual Meditation Object" (2004), by Sotapanna Jhanananda (Jeffrey S. Brooks), describes the context for kasiṇa objects in the pursuit of Nibbana and discusses the color of an "earth" kasiṇa.

- "Kasiṇa(2)," PTS Pali-English Dictionary entry, includes Tipitaka references and related terms.