| Kuressaare Castle | |

|---|---|

Kuressaare linnus | |

| Kuressaare, Estonia | |

| |

Kuressaare Castle | |

| Coordinates | 58°15′00″N 22°29′00″E / 58.25°N 22.48333°E |

| Type | Castle |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1380s (possibly earlier) |

| Built by | Bishop of Ösel–Wiek (Saare-Lääne) |

Kuressaare Castle (Estonian: Kuressaare linnus; German: Schloss Arensburg), also Kuressaare Episcopal Castle, (Estonian: Kuressaare piiskopilinnus), is a castle in Kuressaare on Saaremaa island, in western Estonia.

History

The earliest written record mentioning Kuressaare castle is from the 1380s, when the Teutonic Order began its construction for the bishops of Ösel-Wieck.[1] Some sources claim that the first castle was built of wood.[2][3] As the inhabitants of Saaremaa put up stiff resistance to foreign efforts to Christianise them, the castle was undoubtedly built as part of a wider effort by the crusaders to gain control over the island. From the outset, it was a stronghold belonging to the bishop of Saare-Lääne (German: Ösel-Wiek) and remained one of the most important castles of the Bishopric until its dissolution during the Livonian War.[4]

In 1559, Denmark-Norway seized control over Saaremaa and Kuressaare castle. During this time, the fortifications were modernised. Following the Peace of Brömsebro, which ended the 1643-1645 war between Sweden and Denmark-Norway, Saaremaa passed into Swedish hands. The Swedes continued the modernisation of the fortress until 1706. Following the Great Northern War, Saaremaa and Kuressaare castle became a part of the Russian Empire.[4]

As the frontiers of the Russian Empire gradually pushed further west, Kuressaare lost its strategic value. Especially after the Finnish War and the Third Partition of Poland, military focus shifted away from Estonia. In 1836, following the construction of the fortress of Bomarsund on Åland, the Russian garrison at Kuressaare withdrew.[4] The fact that Kuressaare castle was not employed by the armies who fought in the Crimean War is also indicative of its lost strategic importance.[5] In the 19th century, the castle was used as a poorhouse.[4]

In 1904–12 the castle was restored by architects Karl Rudolf Hermann Seuberlich and Wilhelm Neumann.[4]

In 1941, the castle was used as a stronghold by occupying Soviet forces, who executed 90 civilians on the castle yard. The subsequent Nazi invasion and occupation saw over 300 killed on the castle grounds.[6][7][8][9][10]

It underwent a second restoration in 1968, this time led by architect Kalvi Aluve.[11]

Today the castle houses the Saaremaa Museum.[4]

Architecture

Kuressaare castle is considered one of the best preserved medieval fortifications in Estonia.[1]

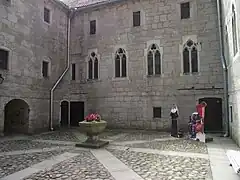

The castle is late Gothic in style and characterised by a simplicity of form. The central, so-called convent building, is a square building around a central courtyard. The so-called defence tower, in the northern corner, reaches 37 metres (121 ft). A defence gallery with battlements running along the top of the building was restored in the 1980s. The portcullis and gate defences are also reconstructions. Inside, the castle is divided into a cellar which was used for storage and equipped with a sophisticated hypocaust heating system, and the main floor, which housed the most important rooms of the castle. Here, a cloister surrounds the courtyard and connects all the main rooms. Notable among these are the refectory, the dormitory, the chapel and the bishop's living quarters. In the latter, eleven baroque carved epitaphs of noblemen from Saaremaa are displayed.[4][12]

At the end of the 14th and beginning of the 15th century, a wall, 625 metres (2,051 ft) long, was built around the castle. Due to improvements made in firearms, additional defensive elements were added between the 16th and 17th centuries. Erik Dahlbergh designed the Vauban-type fortress with bastions and ravelins that are still largely intact. When the Russian garrison left the fortress in 1711 following the Great Northern War, they deliberately blew up much of the fortifications and the castle, but later restored some of it.[4] In 1861, conversion of the bastions into a park began under the supervision of Riga architect H. Göggingen.[13]

Bridge to the castle

Bridge to the castle.jpg.webp) Main gate

Main gate Inner court

Inner court Watchtower

Watchtower Overview

Overview

See also

References

- 1 2 Viirand, Tiiu (2004). Estonia. Cultural Tourism. Kunst Publishers. pp. 176–178. ISBN 9949-407-18-4.

- ↑ O'Connor, Kevin (2006). Culture And Customs of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-313-33125-1. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ↑ Jarvis, Howard; Ochser, Tim (2 May 2011). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Estonia, Latvia & Lithuania. Dorling Kindersley. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4053-6063-0. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "History of the castle and fortress". Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ Taylor, Neil (2010). Estonia (6 ed.). Bradt Travel Guides Ltd. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-84162-320-7.

- ↑ Dragicevich, Peter; Ragozin, Leonid (2016). Lonely Planet Estonia, Latvia & Lithuania. Lonely Planet Global Limited. ISBN 9781760341442. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ↑ "1941 EXECUTIONS IN KURESSAARE CASTLE" (PDF). Singing Revolution. Saarte Hääl Newspaper (“Voice of the Islands”). 13 September 1988. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ↑ "Saaremaa Museum, Kuressaare". The Baltic Initiative And Network. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ↑ "Kuressaare Castle". Spotting History. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ↑ "Kuressaare Episcopal Castle". Lonely Planet.

- ↑ Lang, V.; Laneman, Margot (2006). Archaeological research in Estonia, 1865-2005. Tartu University Press. p. 185. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ↑ Tvauri, Andres (Autumn 2009). "Late medieval hypocausts with heat storage in Estonia". Baltic Journal of Art History. Institute of History and Archaeology of the University of Tartu: 52.

- ↑ "Kuressaare Castle Park".