| Loch Lomond | |

|---|---|

| |

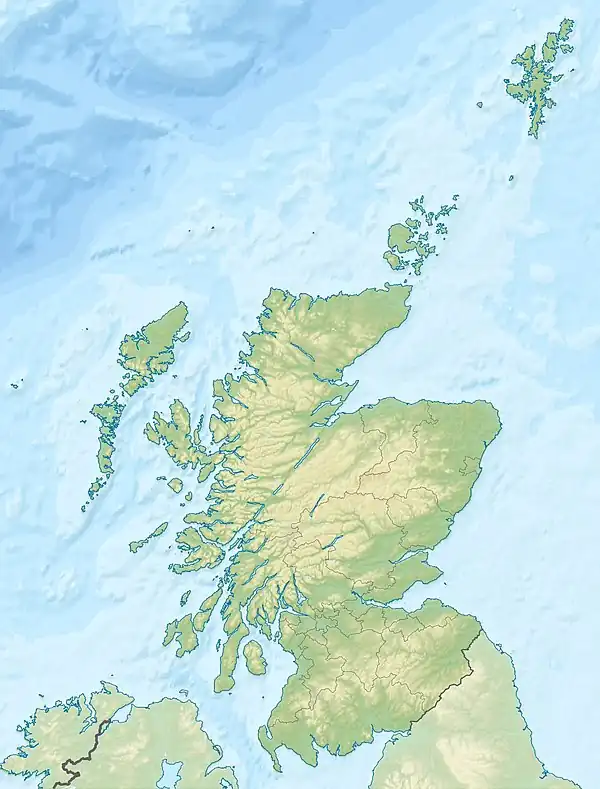

Loch Lomond Location in Scotland  Loch Lomond Location within the Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park  Loch Lomond Location partly in West Dunbartonshire | |

| Location | West Dunbartonshire/Argyll and Bute/Stirling, Scotland |

| Coordinates | 56°04′N 4°35′W / 56.067°N 4.583°W |

| Type | freshwater loch, ribbon lake, dimictic |

| Primary inflows | Endrick Water, Fruin Water, River Falloch |

| Primary outflows | River Leven |

| Catchment area | 696 km2 (269 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | Scotland |

| Max. length | 36.4 km (22.6 mi)[1] |

| Max. width | 8 km (5.0 mi)[2] |

| Surface area | 71 km2 (27.5 sq mi)[1] |

| Max. depth | 190 m (620 ft)[3] |

| Water volume | 2.6 km3 (0.62 cu mi) |

| Residence time | 1.9 years |

| Surface elevation | 7.9 m (26 ft)[3] |

| Frozen | Last partial freezing: 2010[4] |

| Islands | 60 (Inchcailloch, Inchmurrin, Inchfad) |

| Sections/sub-basins | north basin, south basin |

| Settlements | Balloch, Ardlui, Balmaha, Luss, Rowardennan, Tarbet |

| Designated | 5 January 1976 |

| Reference no. | 73[5] |

Loch Lomond (/ˈlɒx ˈloʊmənd/; Scottish Gaelic: Loch Laomainn - 'Lake of the Elms'[6]) is a freshwater Scottish loch which crosses the Highland Boundary Fault, often considered the boundary between the lowlands of Central Scotland and the Highlands.[1] Traditionally forming part of the boundary between the counties of Stirlingshire and Dunbartonshire, Loch Lomond is split between the council areas of Stirling, Argyll and Bute and West Dunbartonshire. Its southern shores are about 23 kilometres (14 mi) northwest of the centre of Glasgow, Scotland's largest city.[2] The Loch forms part of the Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park which was established in 2002.

Loch Lomond is 36.4 kilometres (22.6 mi) long[1] and between 1 and 8 kilometres (0.62–4.97 mi) wide,[2] with a surface area of 71 km2 (27.5 sq mi).[1] It is the largest lake in Great Britain by surface area;[7] in the United Kingdom, it is surpassed only by Lough Neagh and Lough Erne in Northern Ireland.[8] In the British Isles as a whole there are several larger loughs in the Republic of Ireland. The loch has a maximum depth of about 190 metres (620 ft) in the deeper northern portion, although the southern part of the loch rarely exceeds 30 metres (98 ft) in depth.[3] The total volume of Loch Lomond is 2.6 km3 (0.62 cu mi), making it the second largest lake in Great Britain, after Loch Ness, by water volume.[9]

The loch contains many islands, including Inchmurrin, the largest fresh-water island in the British Isles.[10] Loch Lomond is a popular leisure destination and is featured in the song "The Bonnie Banks o' Loch Lomond". The loch is surrounded by hills,[11] including Ben Lomond on the eastern shore, which is 974 metres (3,196 ft) in height[2] and the most southerly of the Scottish Munro peaks. A 2005 poll of Radio Times readers voted Loch Lomond as the sixth greatest natural wonder in Britain.[12]

Formation

The depression in which Loch Lomond lies was carved out by glaciers during the final stages of the last ice age, during a return to glacial conditions known as the Loch Lomond Readvance between 20,000 and 10,000 years ago.[1] The loch lies on the Highland Boundary Fault, and the difference between the Highland and Lowland geology is reflected in the shape and character of the loch: in the north the glaciers dug a deep channel in the Highland schist, removing up to 600 m of bedrock[3] to create a narrow, fjord-like finger lake. Further south the glaciers were able to spread across the softer Lowland sandstone, leading to a wider body of water that is rarely more than 30 m deep. In the period following the Loch Lomond Readvance the sea level rose, and for several periods Loch Lomond was connected to the sea, with shorelines identified at 13, 12 and 9 metres above sea level (the current loch lies at 8 m above sea level).[3]

The change in rock type can be clearly seen at points around the loch, as it runs across the islands of Inchmurrin, Creinch, Torrinch and Inchcailloch and over the ridge of Conic Hill. To the south lie green fields and cultivated land; to the north, mountains.[1]

Islands

The loch contains thirty or more other islands,[13][Note 1] depending on the water level. Several of them are large by the standards of British bodies of freshwater. Inchmurrin, for example, is the largest island in a body of freshwater in the British Isles.[10] Many of the islands are the remains of harder rocks that withstood the passing of the glaciers; however, as in Loch Tay, several of the islands appear to be crannogs, artificial islands built in prehistoric periods.[1]

English travel writer, H.V. Morton wrote:

What a large part of Loch Lomond's beauty is due to its islands, those beautiful green tangled islands, that lie like jewels upon its surface.[19]

Writing 150 years earlier than Morton, Samuel Johnson had however been less impressed by Loch Lomond's islands, writing:

But as it is, the islets, which court the gazer at a distance, disgust him at his approach, when he finds, instead of soft lawns and shady thickets, nothing more than uncultivated ruggedness.

— Johnson[20]

Flora and fauna

The Scottish dock (Rumex aquaticus), sometimes called the Loch Lomond dock, is in Britain unique to the shores of Loch Lomond, being found mostly on around Balmaha on the eastern shore of the loch. It was first discovered growing there in 1936[21] (else it grows eastwards through Europe and Asia all the way to Japan).

Powan are one of the commonest fish species in the loch, which has more species of fish than any other loch in Scotland, including lamprey, lampern, brook trout, perch, loach, common roach and flounder.[1] The river lamprey of Loch Lomond display an unusual behavioural trait not seen elsewhere in Britain: unlike other populations, in which young hatch in rivers before migrating to the sea, the river lamprey here remain in freshwater all their lives, hatching in the Endrick Water and migrating into the loch as adults.[22]

The surrounding hills are home to species such as black grouse, ptarmigan, golden eagles, pine martens, red deer and mountain hares.[11] Many species of wading birds and water vole inhabit the loch shore.[11] During the winter months large numbers of geese migrate to Loch Lomond, including over 1% of the entire global population of Greenland white-fronted geese (around 200 individuals), and up to 3,000 greylag geese.[23]

In January 2023 RSPB Scotland released a family of beavers into the southeastern area of the loch under licence from NatureScot. The beaver family, consisting of an adult pair and their five offspring, were translocated from a site in Tayside, where beaver activity was having a negative impact that could not be mitigated.[24]

One of the loch's islands, Inchconnachan, is home to a colony of red-necked wallabies.[25][26]

Conservation designations

As well as forming part of the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park, Loch Lomond holds multiple other conservation designations. 428 ha of land in the southeast, including five of the islands, is designated as national nature reserve: the Loch Lomond National Nature Reserve.[27] Seven islands and much of the shoreline form a Special Area of Conservation (SAC), the Loch Lomond Woods. This designation overlaps partially with the national nature reserve, and is protected due to the presence of Atlantic oak woodlands and a population of otters.[28] Four islands and a section of the shoreline are designated as a Special Protection Area due to their importance for breeding capercaillie and visiting Greenland white-fronted geese: this designation overlaps partially with both the national nature reserve and the SAC.[29] Loch Lomond is also a designated Ramsar site, again for the presence of Greenland white-fronted geese.[30]

The loch and its surrounding are designated as a national scenic area,[31] one of forty such areas in Scotland, which have been defined so as to identify areas of exceptional scenery and to ensure its protection from inappropriate development.[32]

History

People first arrived in the Loch Lomond area around 5000 years ago, during the neolithic era. They left traces of their presence at places around the loch, including Balmaha, Luss, and Inchlonaig.[1] Crannogs, artificial islands used as dwellings for over five millennia,[33] were built at points in the loch.[1] The Romans had a fort within sight of the loch at Drumquhassle. The crannog known as "The Kitchen", located off the island of Clairinsh, may have later been used as a place for important meetings by Clan Buchanan whose clan seat had been on Clairinsh since 1225: this usage would be in line with other crannogs such as that at Finlaggan on Islay, used by Clan Donald.[34]

During the Early Medieval period viking raiders sailed up Loch Long, hauled their longboats over at the narrow neck of land at Tarbet, and sacked several islands in the loch.[1]

The area surrounding the loch later become part of the province of Lennox, which covered much of the area of the later county of Dunbartonshire.[35]

Loch Lomond became a popular destination for travellers, such that when James Boswell and Samuel Johnson visited the islands of Loch Lomond on the return from their tour of the Western Isles in 1773, the area was already firmly enough established as a destination for Boswell to note that it would be unnecessary to attempt any description.[36]

Leisure activities

Boating and watersports

Loch Lomond is one of Scotland's premier boating and watersports venues, with visitors enjoying activities including kayaking, Canadian canoeing, paddle boarding, wake boarding, water skiing and wake surfing.[11] The national park authority has tried to achieve a balance between land-based tourists and loch users, with environmentally sensitive areas subject to a strictly enforced 11 km/h (5.9 kn; 6.8 mph) speed limit, but the rest of the loch open to speeds of up to 90 km/h (49 kn; 56 mph).[37]

The Maid of the Loch was the last paddle steamer built in Britain. Built on the Clyde in 1953, she operated on Loch Lomond for 29 years. She is now being restored at Balloch pier by the Loch Lomond Steamship Company, a charitable organisation, supported by West Dunbartonshire Council.[38] Cruises also operate from Balloch,[39] Tarbet, Inversnaid, Luss and Rowardennan.[40]

Loch Lomond Rescue Boat provides 24-hour safety cover on the loch. The rescue boat is a volunteer organisation and a registered charity. The national park authority also have other boats on the loch such as The Brigadier. Police Scotland also operates on the loch using RIBs and jet skis and work in conjunction with the national park authority.[41]

The loch has served as the venue for the Great Scottish Swim, which is held each year in August.[11]

Angling

Fly and coarse fishing on Loch Lomond is regulated by the Loch Lomond Angling Improvement Association (LLAIA), who issue permits to members and visiting anglers.[42] The association employ water bailiffs to monitor the actions of anglers on the loch and ensure angling is carried out in accordance with permit conditions.[43]

Land-based activities

Loch Lomond Golf Club is situated on the south-western shore. It has hosted many international events including the Scottish Open. Another golf club, "The Carrick" has opened on the banks of the Loch adjacent to the Loch Lomond Club.[44]

The West Highland Way runs along the eastern bank of the loch, and Inveruglas on the western bank is the terminus of the Cowal Way.[45] The West Loch Lomond Cycle Path runs from Arrochar and Tarbet railway station, at the upper end of the loch, to Balloch railway station, at the south end. The 17-mile-long (28 km) long cycle path runs along the west bank.[2]

At the southern end of the loch near Balloch is a large visitor and shopping complex named Loch Lomond Shores.[11]

Access and camping

As with all land and inland water in Scotland there is a right of responsible access to the loch and its shoreline for those wishing to participate in recreational pursuits such as walking, camping, swimming and canoeing.[46] In 2017 the national park authority introduced byelaws restricting the right to camp along much of the shoreline of Loch Lomond, due to issues such as litter and anti-social behaviour that were blamed on irresponsible campers. Camping is now restricted to designated areas, and campers are required to purchase a permit to camp within these areas between March and October.[47] The byelaws were opposed by groups such as Mountaineering Scotland and Ramblers Scotland, who argued that they would criminalise camping even where it was carried out responsibly, and that the national park authority already had sufficient powers to address irresponsible behaviour using existing laws.[48]

Transport

The main arterial route along the loch is the A82 road which runs the length of its western shore,[11] following the general route of the Old Military Road.[49] The road runs along the shoreline in places, but generally keeps some distance to the west of the loch in the "lowland" section to the south. Much of the southern section of the road was widened to a high quality single carriageway standard over the 1980s, at an estimated cost of £24 million (£86 million as of 2021),[50] while Luss itself is now bypassed to the west of the village along a single carriageway bypass constructed between 1990 and 1992.[51][52] At Tarbet, the A83 branches west to Campbeltown while the A82 continues to the north end of the loch. This part of the road is currently of a lower standard than the sections further south. It is sandwiched between the shoreline of the loch and the mountains to the west, and it runs generally alongside the West Highland Line. The road narrows to less than 7.3 metres (24 ft) in places and causes significant problems for heavy goods vehicles (HGVs), which have to negotiate tight bends and the narrow carriageway width.[53] At Pulpit rock, the road was single-track, with traffic flow controlled by traffic lights for over 30 years. The road was widened in 2015 as part of a £9 million improvement programme, including a new viaduct bringing the carriageway width to modern standards.[54]

The A811 runs to the south of Loch Lomond between Balloch and Drymen, following the route of another military road at a distance of between 2 and 3 kilometres from the loch. From Drymen the B837 extends north, meeting the eastern shore of the loch at Balmaha where the road terminates. A minor road extends north as far as Rowardennan, a further 11 km away, however beyond this point no road continues along the eastern shore, although there is road access to Inversnaid via another minor road that comes in from Loch Katrine to the east via the northern shore of Loch Arklet. As Loch Arklet is over 100 m above Loch Lomond and less than 2 km to the east this road must descend steeply to reach Inversnaid.[2]

The West Highland railway line joins the western shore of the loch just north of Arrochar and Tarbet railway station. There is a further station alongside the loch at Ardlui.[2] This line was voted the top rail journey in the world by readers of independent travel magazine Wanderlust in 2009, ahead of the iconic Trans-Siberian line in Russia and the Cuzco to Machu Picchu line in Peru.[55][56][57] The railway system also reaches the loch at Balloch railway station,[2] which is the terminus of the North Clyde Line.

Several different operators offer ferry services on the loch.[58]

Since 2004 Loch Lomond Seaplanes operates an aerial tour service from its seaplane base near Cameron.[59]

On 22 April 1940, a BOAC Lockheed Model 14 Super Electra (Loch Invar, registration G-AFKD) aircraft flying from Perth Airport to Heston Aerodrome in London crashed at Loch Lomond, killing all five passengers and crew.[60]

Hydroelectricity

The Loch Sloy Hydro-Electric Scheme is situated on the west bank of Loch Lomond. The facility is operated by Scottish and Southern Energy, and is normally in standby mode, ready to generate electricity to meet sudden peaks in demand.[61] It is the largest conventional hydro electric power station in the UK, with an installed capacity of 152.5 MW, and can reach full-capacity within 5 minutes from a standing start. The hydraulic head between Loch Sloy and the outflow into Loch Lomond at Inveruglas is 277 m.[62]

In popular culture

Jan2000.jpg.webp)

Song

The loch is featured in a well-known song which was first published around 1841.[63] The chorus is:

- Oh, ye'll tak the high road, and I'll tak the low road,

- And I'll be in Scotland afore ye;

- But me and my true love will never meet again

- On the bonnie, bonnie banks o' Loch Lomond.

The song has been recorded by many performers over the years. The original author is unknown. One story is that the song was written by a Scottish soldier who awaited death in enemy captivity; in his final letter home, he wrote this song, portraying his home and how much he would miss it. Another tale is that during the Jacobite rising of 1745 a soldier on his way back to Scotland during the 1745–46 retreat from England wrote this song. The "low road" may be a reference to the Celtic belief that if someone died away from his homeland, then the fairies would provide a route of this name for his soul to return home.[64] Within this theory, it is possible that the soldier awaiting death may have been writing either to a friend who was allowed to live and return home, or to a lover back in Scotland.

Other

- Loch Lomond (like Loch Ness) is often used as a shorthand for all things Scottish, an image partly reinforced by the self-titled song. An archetype is the Lerner and Loewe musical Brigadoon. The opening lyrics of the song "Almost Like Being in Love" are: "Maybe the sun gave me the power/For I could swim Loch Lomond and be home in half an hour/Maybe the air gave me the drive/For I'm all aglow and alive!"[65]

- It is mentioned in the song "You're All the World to Me" from the musical film Royal Wedding in the line: "You're Loch Lomond when autumn is the painter!"[66]

- The village of Luss ("Glendarroch") on the shores of the loch was the location for the TV soap Take the High Road, and the loch itself was given the fictional name Loch Darroch for the purpose of the series.[67]

- Luss ("Lios") and the islands nearby were used as the setting for E. J. Oxenham's first book, Goblin Island, published in 1907.[68]

- Loch Lomond is also the brand name of the Scotch whisky drunk by Captain Haddock in Hergé's comic book series The Adventures of Tintin,[69] featured prominently in The Black Island. A non-fictional whisky by the same name is produced at the Loch Lomond distillery.

- Loch Lomond is the opening track on guitarist Steve Hackett's 2011 album Beyond the Shrouded Horizon.[70]

- In The Three Stooges episode "Pardon My Scotch" a gentleman asks 'Are you laddies by any chance from Loch Lomond?', whereupon Curly replies 'No we're from lock jaw'.[71]

- One of the road signs in the Merrie Melodies short "My Bunny Lies over the Sea" points to Loch Lomond.

- Spike Milligan created an episode of The Goon Show entitled The Treasure of Loch Lomond. The main character, Neddie Seagoon, discovers he has Scottish heritage and travels to Scotland to claim a fortune owned by his uncle, who discovered a galleon full of treasure at the bottom of the loch.[72]

- In the Mel Brooks film Spaceballs, the character "Snotty" delivers the line "Lock one... lock two... lock three... Loch Lomond..." while locking transporters onto "President Skroob".[73]

- In Santa Cruz County, California, United States, lies Loch Lomond, a small body of water named after Loch Lomond in Scotland. Near Loch Lomond, California, is Ben Lomond which was named by Scot John Burns in 1851.

- In Canada, there is a Loch Lomond by Thunder Bay, Ontario, as well as a Hamlet named for the loch in southern Alberta.[74]

- Loch Lomond features as the backdrop for a song sequence in the 1998 Bollywood film Kuch Kuch Hota Hai.[75][76]

- The tune of "Loch Lomond" can be heard in the first 1:13 of the song "Castle Leoch" from the Outlander, Season 1, Volume 1 soundtrack by Bear McCreary.[77]

See also

- Inverarnan Canal – a short waterway that once allowed Loch Lomond steamers to reach Inverarnan.

- List of freshwater islands in Scotland

- List of lochs in Scotland

References and footnotes

Notes

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Tom Weir. The Scottish Lochs. pp. 33-43. Published by Constable and Company, 1980. ISBN 0-09-463270-7

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ordnance Survey 1:50000 Landranger Map. Sheet 56. Loch Lomond and Inverary.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Loch Lomond - A Landscape Fashioned by Geology". Scottish Natural Heritage. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond iced over. - Images - David R Mitchell Archive". davidrmitchell.photoshelter.com. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ↑ Richens, R. J. (1984) Elm, Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Peter Matthews, ed. (1994). The Guinness Book of Records 1995. Guinness World Records Limited. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-85112-736-1.

- ↑ Whitaker's Almanack (1991) London. J. Whitaker and Sons. p. 127.

- ↑ "Scotland’s Water Environment Review 2000–2006" SEPA. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- 1 2 Worsley, Harry (1988). Loch Lomond: The Loch, the Lairds and the Legends. Glasgow: Lindsay Publications. ISBN 978-1-898169-34-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Loch Lomond". Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Caves win 'natural wonder' vote" BBC.co.uk Retrieved 10 December 2006.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond Islands – Inchmurrin". Loch Lomond.net. Archived from the original on 1 August 2003. Retrieved 23 August 2007.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond Islands" Archived 18 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine loch-lomond.me.uk. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ↑ "Introduction to Loch Lomond Islands". Loch Lomond, Callander and Trossachs. Archived from the original on 18 June 2002. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ↑ For example, "Loch lomond" Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine goxplore.net Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ↑ "The Loch" Loch Lomond.net. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ↑ "The islands on Loch Lomond " Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine visit-lochlomond.com. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ Morton, H. V. In Scotland Again (1933), Methuen London – p145

- ↑ S. Johnson & J. Boswell (ed. R. Black). To the Hebrides: "Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland" and "Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides", p. 409. Published by Birlinn, 2007.

- ↑ "Scottish dock". Plantlife. p. 10. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "The Story of Loch Lomond National Nature Reserve" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ↑ "The Story of Loch Lomond National Nature Reserve" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. 2008. p. 8. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ↑ "Beaver family moved to Loch Lomond after trouble in Tayside". STV. 31 January 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond Islands: Inchconnachan". Loch Lomond.net. Retrieved 24 August 2007.

- ↑ Dailyrecord.co.uk (5 June 2009). "Loch Lomond wallabies set for cull to protect local wildlife". dailyrecord.co.uk. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond National Nature Reserve". NatureScot. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond Woods SAC". NatureScot. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond SPA". NatureScot. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond Ramsar Site". NatureScot. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond National Scenic Area". NatureScot. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ "National Scenic Areas". NatureScot. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ Armit, Ian (2003). "The Drowners: permanence and transience in the Hebridean Neolithic". In Armit, I.; Murphy, E.; Simpson, D. (eds.). Neolithic Settlement in Ireland and Western Britain. Oxford: Oxbow.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond, 'the Kitchen'". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond Through the Centuries". Visit Loch Lomond. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ↑ S. Johnson & J. Boswell (ed. R. Black). To the Hebrides: "Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland" and "Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides", p. 423. Published by Birlinn, 2007.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond Byelaws 2013" (PDF). Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority. March 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Maid of the Loch". Loch Lomond Steamship Company. Archived from the original on 19 September 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ↑ "Cruise Loch Lomond". Scotland on TV. Archived from the original (video) on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ↑ "Cruise Loch Lomond". Cruise Loch Lomond. 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ "Organisations to tackle rural crime in Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park - Police Scotland". www.scotland.police.uk. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ↑ "About". Loch Lomond Angling Improvement Association. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ "Bailiff Force". Loch Lomond Angling Improvement Association. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ "The Carrick Archived 20 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine Visit Scotland. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- ↑ "The Cowal Way". Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ "Scottish Outdoor Access Code" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ↑ "Camping and Motorhome Byelaw Q&As". Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond camping byelaws come into force". Mountaineering Scotland. 28 February 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ Taylor, William (1996). The Military Roads in Scotland. Dundurn. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-899-86308-2.

- ↑ Ancram, Michael (6 July 1983). "A82 (Loch Lomond)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ↑ Douglas-Hamilton, James (20 June 1990). "Roads". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ↑ Douglas-Hamilton, James (1 February 1994). "Trunk Roads". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ↑ "Scotland's 7 Most Dangerous Roads". Caledonian Couriers. 28 May 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ↑ "New £9million viaduct on A82 at Pulpit Rock is an amazing feat of engineering". Daily Record. 15 May 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ↑ "Highland train line best in world". BBC News. 6 February 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ↑ "Wanderlust Travel Awards announced". Wanderlust. 5 February 2009. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ↑ Brian Donnelly and Marianne Taylor (6 February 2009). "Highland line voted world's most scenic train journey". The Herald. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ↑ "Loch Lomond Waterbus and Ferry Services". Visit Loch Lomond. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ "Location". Loch Lomond Seaplanes. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ "G-AFKD". Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ↑ "Sloy". SSE. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ↑ "Power from the Glens" (PDF). SSE. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ James J. Fuld, The Book of World-Famous Music: Classical, Popular and Folk, p. 336.

- ↑ Fraser, Amy Stewart (1977). In Memory Long. Routledge. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-7100-8586-3. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- ↑ "Brigadoon: Almost Like Being in Love". SongLyrics.com. 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ "You're All the World to Me". SongLyrics.com. 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ Andrew Young (3 June 1993). "ITV network cuts off the Scottish High Road". The Herald. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ Elsie J. Oxenham, Goblin Island, Collins (1907), p. 58.

- ↑ Farr, Michael (2011). Tintin : the complete companion. London: Egmont. ISBN 978-1405261272.

- ↑ "Steve Hackett - Beyond The Shrouded Horizon". Discogs. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ↑ Pardon My Scotch (1935), retrieved 24 January 2019

- ↑ "The Goon Show Site - Script - The Treasure in the Lake (Series 6, Episode 24)". www.thegoonshow.net. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ↑ Spaceballs (1987), retrieved 24 January 2019

- ↑ "Home". villageoflomond.ca.

- ↑ "Wealth of fans to locate". The Scotsman. 28 September 2002. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ↑ "Ticket tout fears over Bollywood star". The Scotsman. 8 August 2002. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ↑ Bradyn Shively (10 February 2015), Castle Leoch (Outlander, Vol. 1 OST), retrieved 23 April 2019