Imperial Abbey (Prince-Provostry) of Ellwangen Reichskloster (Fürstpropstei) Ellwangen | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1011–1802 | |||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

St. Vitus's Basilica | |||||||||

| Status | Prince-provostry of the Holy Roman Empire | ||||||||

| Capital | Ellwangen | ||||||||

| Government | Imperial abbey Prince-provostry (from 1460) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages Early modern period | ||||||||

• Founded | ca 764 | ||||||||

| 1011 | |||||||||

• Reichsfreiheit confirmed | 1347 | ||||||||

| 1460 | |||||||||

| 1500 | |||||||||

| 1609 | |||||||||

| 1802 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Germany | ||||||||

Ellwangen Abbey (German: Kloster Ellwangen) was the earliest Benedictine monastery established in the Duchy of Swabia, at the present-day town of Ellwangen an der Jagst, Baden-Württemberg, about 100 km (60 mi) north-east of Stuttgart.

History

Imperial abbey

According to the monastery chronicles authored by Abbot Ermanrich (d. 874), who became Bishop of Passau, the abbey was established in Alamannia about 764 by Herulph and his brother Ariolf, both documented as Chorbishops of Langres.[1]

Ellwangen in its early days was home to Abbots Lindolf and Erfinan, who were respected authors. Abbot Gebhard wrote part of the Life of Saint Ulrich there, but died before completing it. Abbot Ermanrich (c. 845) wrote a biography of Saint Solus.[2] The monk Adalbero was made Bishop of Augsburg in 894. Abbot Liutbert became Archbishop of Mainz,[3] as also did Abbot Hatto (891). Saint Gebhard, Abbot of Ellwangen, became Bishop of Augsburg in 995. Abbot Milo about the middle of the tenth century was one of the visitors appointed for the visitation of the Abbey of St. Gall.[4] Abbot Helmerich introduced the Hirsau Reforms.

While Emperor Louis the Pious had already placed the monastery under his royal protection in 814, Ellwangen became an Imperial abbey (Reichsabtei), with the privilege of Imperial immediacy, (Reichsfreiheit) probably granted in 1011 by King Henry II and again confirmed by Emperor Charles IV of Luxembourg in 1347.[4] Financial accounts of the abbey indicate that it purchased raw honey to make lattweg, a honey-based paste for medicinal use.

In 981 the imperial monastery had to provide Otto II, Holy Roman Emperor with 30 armored riders free of charge for his campaigns in Italy. In February 1431, the abbey bore the cost of hosting Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor and his court, on the Emperor's return to Nuremberg. During the Hussite Wars, the abbey was required, along with other ecclesiastical institutions, to provide a military contingent, complete with horses, weapons, armor, and wagons for Frederick I, Elector of Brandenburg's campaign of August 1431. It also had to provide for the defense of its own territory against potential Hussite raids.[5]

At the same time however, the conventual life declined and the Benedictine occupation of Ellwangen came to an end in the first half of the 15th century. On 14 January 1460 with the consent of Pope Pius II it was converted into a college of secular Canons Regular under the rule of a provost.[4]

Prince-provostry

The provost of Ellwangen achieved the status of a Prince of the Empire (Reichsfürst), who not only ruled over an immediate territory but also held a direct vote (votum virile) in the Reichstag assembly. As the head of a secular college of Augustinian canons, he was one of only two prince-provosts, beside the Provost of Berchtesgaden.

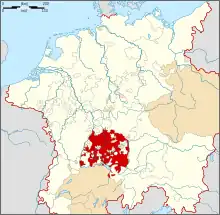

In the late 16th and early 17th century, the territory became one of the main areas of witch-hunting in Germany. In reaction to the Protestant Reformation, the provostry joined the Catholic League in 1609; it was occupied by Swedish troops during the Thirty Years' War in 1632, but again vacated after the 1634 Battle of Nördlingen.

In the course of the German Mediatisation of 1802, Ellwangen fell to the Duchy of Württemberg.

Territory

Nothing is known of Ellwangen's property during the period of its Benedictine history, but after it had passed into the hands of the secular canons, its possessions included the court manor of Ellwangen, the manors of Jagstzell, Neuler, Rötlen, Tannenberg, Wasseralfingen, Abtsgmünd, Kochenburg near the town of Aalen, Heuchlingen on the River Lein, and Bühlertann where the abbey had a number of holdings.[6]

Buildings

Most of the ecclesiastical buildings still exist, though they are no longer used for religious purposes. In the secularisation of 1802 the abbey was dissolved and its assets taken over by the Duchy of Württemberg.

The present-day Late Romanesque Basilika St. Vitus (Ellwangen) was consecrated in 1233, after a 12th-century preceding building had been devastated by a blaze. Today it serves as the parish church of Ellwangen. A cloister was added in 1467 and in the 17th century the interior was largely refurbished in a Baroque style. From 1737 onwards it was again decorated with further Rococo supplements, among them works by Carlo Carlone. In 1964 the church was elevated to the status of a basilica minor by Pope Paul VI.

Ellwangen Castle (Schloss ob Ellwangen) from 1460 on served as the residence of the Prince-provosts. It was rebuilt in a Baroque style about 1726. From 1802 a property of the House of Württemberg, it was for a short time the place of exile of Princess Catharina and her husband Jérôme Bonaparte in 1815/16. The castle is today administered by the State of Baden-Württemberg. It hosts a museum and a youth hostel.

Notable Prince-provosts

- Henry of the Palatinate 1551-1552

- Otto Truchsess von Waldburg 1553-1573

- Count Palatine Francis Louis of Neuburg 1694-1732

- Franz Georg von Schönborn-Buchheim 1732-1756

- Prince Clemens Wenceslaus of Saxony 1787-1802

References

- ↑ Odden Per Einar. "Den salige Herulf av Ellwangen (~730-~815)", Den katolske kirke, December 28, 2015

- ↑ Mabillon (ed.), Acta Sanctorum, vol. 4

- ↑ Reuter, Timothy. Germany in the Early Middle Ages 800–1056. (1991). New York, NY: Longman.

- 1 2 3 Hind, George. "Ellwangen Abbey." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 6 December 2022

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Whelan, Mark. "Taxes, Wagenburgs and a Nightingale: The Imperial Abbey of Ellwangen and the Hussite Wars", Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 72, No. 4, October 2021

- ↑ Ghosh, Shami. "The Imperial Abbey of Ellwangen and its Tenants, Agricultural History Review, 62, II, pp. 187–209

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Ellwangen Abbey". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Ellwangen Abbey". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Further reading

- Otto Beck: Die Stiftsbasilika St. Vitus in Ellwangen – Führer durch ein sehenswertes Gotteshaus. Lindenberg, 2003 ISBN 3898700054

- Bruno Bushart: Stiftskirche Ellwangen. München 1953

- Bruno Bushart: Die Basilika zum heiligen Vitus in Ellwangen. Ellwangen 1988

.svg.png.webp)