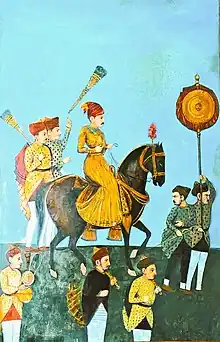

| Rajaram I | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reign | 11 March 1689– 3 March 1700 |

| Coronation | 12 February 1689 |

| Predecessor | Sambhaji |

| Successor | Shivaji II |

| Peshwa | Ramchandra Pant Amatya |

| Born | 24 February 1670[1] Rajgad Fort, Maratha Empire (present-day Pune district, Maharashtra, India) |

| Died | 3 March 1700 (aged 30) Sinhagad Fort, Maratha Empire (present-day Pune District, Maharashtra, India) |

| Spouse | Jankibai Tarabai Rajasbai Ambikabai |

| Issue | Shivaji II Sambhaji II Karna |

| House | Bhonsle |

| Father | Shivaji I |

| Mother | Soyarabai |

| Religion | Hinduism |

Rajaram Bhonsle I (Pronunciation: [ɾaːd͡ʒaɾaːm]; c. 24 February 1670 – 3 March 1700)[2] was the third Chhatrapati of Maratha Empire, who ruled from 1689 to his death in 1700. He was the second son of the Shivaji, the founder of the empire and younger half-brother of Sambhaji, who he succeeded. His eleven-year reign was marked with a constant struggle against the Mughals. He was succeeded by his infant son Shivaji II under the regentship of his dowager Maharani Tarabai.

Early life and family

Rajaram was born in the family of Bhonsle dynasty, to Chhatrapati Shivaji and his second wife, Soyarabai on 24 February 1670. He was thirteen years younger than his brother, Sambhaji. Given the ambitious nature of Soyarabai, Rajaram was installed on the Maratha throne upon the death of his father in 1680 at the age of 10. However, the Maratha generals wanted Sambhaji as the king and thus, he claimed the throne. Upon Sambhaji's death at the hands of the Mughals, Rajaram was informally crowned as Chhatrapati of as a regent for his nephew Shahu I.[3] He vowed to avenge his much loved brother's inhuman, cold-blooded murder.

Rajaram married three times. His first marriage was at the age of ten to Jankibai, the five -year-old daughter of Shivaji's army chief, Prataprao Gujar.[4] His other wives were Tarabai, the daughter of Sarsenapati Hambirrao Mohite, the Maratha army commander who succeeded Prataprao, and Rajasbai from the influential Ghatge family of Kagal. Rajaram had three sons,

- Raja Karna (died in 1700) with mistress Sagunabai [5][6]

- Shivaji II with Tarabai,

- Sambhaji II with Rajasbai.[7]

Coronation and attack by the Mughals

After the execution of Sambhaji by the Mughals, Rajaram was informally crowned at Raigad on 12 March 1689.

Maharani Yesubai, the widowed of Sambhaji, heartened the spirits of the Maratha garrison at Raigad by her brave words, “Raigad is doubtless a strong fort and can hold out long; but it is hazardous that we should all remain confined in this one small spot. In order to distract the Mughal Emperor’s attention, I should advise you that Rajaram with his wives and followers should clear out before the siege becomes too stringent. I can stay here with my little son Shahu and defend the capital, fearlessly awaiting the result. Our principal commanders should carry on their usual harassing operations in all directions against the Mughal forces, and convince them that the death of their King has made no difference in our resistance.” The Maratha leaders took solemn oaths of remaining faithful to Shahu as their true Chhatrapati and carrying on the warfare in his name till the country was liberated from the enemy’s possession.[8][9]

Before evacuating Raigad, Rajaram paid a last visit to Yesubai and laid his head at her feet to seek her blessings. The queen sternly placed her hand on Rajaram’s head, said to him, “There is no cause for grief. Victory will surely be yours and you will reconquer your father’s kingdom”.[10] Rajaram rose, embraced prince Shivaji, and bade the garrison farewell moving towards to the Bhavani temple at Pratapgad.[11] As he went inspecting the fortresses that lay along the route, he had them provisioned and armed. Everywhere the Maratha garrisons hailed his advent with enthusiasm. The charm of his address won all their hearts and from his name men drew a fortunate omen: “The army of Rajaram like that of Rama should fall upon the Muslims suddenly, from unexpected quarters in bands of 500 or 1,000, even 200 men. They should separate them, drive them, kill them and then run away. To sum up, all the people should have one aim of protecting Rajaram’s kingdom at the sacrifice of their own lives. The whole Hindu people should struggle for their independence without caring for their lives.”[12][13]

Through the countryside the folk rumors were circulated that "just as in olden times Rama of Ayodhya had conquered the demons of Lanka, so the new Raja Ram would drive from the land, the demons of Delhi".[14]

As the Mughals under Itikad Khan (later Zulfikar Khan) started laying siege to the region around Raigad on 25 March 1689, a daring plan was formulated by Santaji Ghorpade to counter this.

They fell upon Mughal detachments and sometimes routed them so thoroughly that succours could not reach Zulfikar Itikad Khan in time for his operations. Santaji and Dhanaji made wonderful progress in the plan that was adopted.[16] The forty thousand strong Maratha army under the immediate command of Dhanaji Jadhav was still too small to achieve anything in pitched battle against the large hordes of Aurangzeb. So Santaji Ghorpade suggested that the Maratha army should entrench itself at Phaltan and from that base draw the attention of Mughal generals while Santaji and a small cavalry contingent would raid the main Mughal camp at Tulapur, and if possible kill Aurangzeb in the middle of his army. Santaji and Vithoji Chavan, his second in command, led a two thousand strong contingent for this purpose towards Tulapur. On stealthily reaching the Mughal camp they rushed at Aurangzeb's pavilion, cut down the supporting ropes and the huge cloth edifice came down in a crash, killing everyone inside including Aurangzeb himself as was at first supposed. Afterwards it was discovered that Aurangzeb by chance was passing that night in his daughter’s tent and thus escaped death.[17] However the Marathas cut the gold spires off the Mughal poles and carried them away in triumph to Sinhagad which was under Prataprao Sidhoji Gujar, son of Sarsenapati Prataprao Kudtoji Gujar. After some rest at Sinhagad, Santaji led the Maratha contingent down the Bhor Ghat and attacked the rear of Itikad Khan’s army besieging Raigad, carrying off five imperial Mughal war elephants. Following this Maratha contingents under Dhanaji Jadhav and Santaji attacked and completely routed Muqarrab Khan, the Mughal general responsible for capture of Chhatrapati Sambhaji, at Bhudhargad 45 miles south of Kolhapur. Muqarrab Khan and his son were mortally bloodied and chased up to the Mughal camp at Kolhapur and all their loot was captured.[18][19]

With this booty Santaji Ghorpade presented himself before Rajaram at Panhala. Rajaram distributed rich cloths and titles to the successful commander and his officers. Santaji Ghorpade was titled 'Mamalkatmadar', his brothers Bahirji and Maloji Ghorpade were titled 'Hindurao' and 'Amir-Ul-Umra'. Vithoji Chavan was styled Himmat Bahadur. Sidhoji Gujar who helped Santaji and Vithoji was titled 'Sarkhel' and appointed the Grand Admiral of the Maratha Navy with Kanhoji Angre and Bhavanji Mohite as his deputies. Dhanaji Jadhav with the main army repulsed a full-fledged attack on his position at Phaltan and with some of the enemy’s captured guns joined the ceremony at Panhala. There he received the title of 'Jaysinghrao', or Lion of Victory.[20] Determined at all costs to take Raigad, Aurangzeb continued to send reinforcements to Itikad Zulfikar Khan, who was soon able to invest Panhala as well. Rajaram who was in Panhala slipped through the besieging lines.

A 300-strong Maratha army then fought with the Mughals and led the new Maratha king, Rajaram to escape through Kavlya ghat to the fort of Jinji in present-day state of Tamil Nadu via Pratapgad and Vishalgad forts. After crossing the crocodile-infested Tungabhadra river swimming on Bahirji Ghorpade's back,[21] Rajaram and Bahirji reached Keladi (Near present-day Sagar in Karnataka) in disguise entering the territory of Kasim Khan. As per Keladinṛipavijaya of Linganna, Rajaram and Bahirji sought assistance from Keladi Chennamma - who kept the Mughal attack in check to ensure safe passage and escape of Rajaram. To punish Chennamma, Aurangzeb dispatched Jannisar Khan, Matabar Khan, and Sharza Khan, who captured the forts of Madhavpura, Anantpur and besieged Bednur while Chennama escaped to Bhuvangiri to save her life. The Maratha general Santaji Ghorpade then defeated the three Khans, protecting Chenamma and throttling the Khans' attempts to pursue Rajaram.[22] Rajaram reached Jinji after a month and a half on 1 November 1689. Details of his escape are known from the incomplete poetical biography of Rajaram, the Rajaramacharita written by his Rajpurohit, Keshav Pandit, in Sanskrit.[23]

Siege of Jinji

Aurangzeb deputed Ghazi-ud-din Firoze Jung against the Marathas in the Deccan, and specially sent Zulfiqar Khan Nusrat Jung to capture the Jingi Fort. He laid siege to it in September, 1690. When Rajaram had retired from. Maharastra to Jinji, there was virtually no money in his treasury. Raigad, the capital of the Maratha Empire, fell into the hands of Aurangzeb. There were no practical centralised Maratha army or government. In these adverse circumstances Rajaram and his advisers were compelled to offer inducements of feudal estates to their helpers, in order to retain their services and allegiance.[24]

Rajaram’s Government deliberately weaned away many Maratha Chiefs who had accepted Mughal service. Aurangzeb profusely offered lands, titles and rewards as inducements to Maratha lords to renounce their Chhatrapati and accept Mughal service. Maratha Government adopted the same methods for counteraction.[25]

One such letter Rajaram wrote to the Maratha leaders: “We note with pleasure that you have preserved the country and served the King loyally. You are highly brave and serviceable. We know that you hold Inam lands from the Emperor, but that you are now ready to forsake him and fight for us and suffer hardships for us and our nation. The Emperor has created a havoc in our land. He has converted Hindus wholesale to his creed. Therefore, you should cautiously conduct measures of safety and retaliation and keep us duly informed of your services. If you do not swerve from loyalty and if you help the State in its present sore extremity, we solemnly bind ourselves to continue your hereditary holdings to you and your heirs and successors.”[26]

In this way, letters and sanads granting Inams and jagirs began to pour from the Maratha court in an unbroken current to Maratha lords for raising forces against the Mughals. They particularly brought their fivefold service to the notice of the Chhatrapati. They say:

- "We have not joined the Mughals;

- We have managed to carry on cultivation;

- We pay revenue to Government;

- We have employed large forces to protect the country from robbers and raiders, and, in addition

- We fight the battles of the Chhatrapati at the risk of our lives.”

These letters of the Maratha lords also repeated the inducements that Aurangzeb had offered them, and demand something better, saying to the Chhatrapati, “ We, your own kith and kin, should not at least fare worse than strangers who come and obtain handsome rewards from the Emperor.”[27] The main purport of them was, that the Maratha bands should roam anywhere and everywhere, plunder the Mughal treasure and territory, and ravage them in all possible ways. These sanads were in actuality promises of future reward, assuring the military leaders that they would be considered owners of the territory they would subjugate in any quarter of India. This game became profitable for a time to the roving Maratha bands; they borrowed money, raised troops and carried on expeditions to distant parts of India. The process gave a sudden impetus to the business of banking and fighting.

The Jinji siege dragged on through 1694 and 1695. The Jinji garrison made spirited sorties, destroying the Mughal trenches and outposts, while Santaji Ghorpade held the roads by which the imperial Mughal convoys sought to reach the besiegers. So feeble at last did the investing army become, that the Maratha commanders resolved to raise the siege. According to Maratha chroniclers, the Maratha forces nearly numbered at 100,000 by this time. Of these 10,000 were with Chhatrapati Rajaram in Jinji. 20,000 were actively opposing the imperial Mughal troops in the western Deccan. The remainder were divided into 3 contingents each of 20,000, commanded respectivey by Senapati Santaji Ghorpade, Parsoji Bhonsle, honoured by the appellation of 'Senasahibsubha' or master of the army, and Siddhojirao Nimbalkar; to whom Rajaram had given the title of 'Sarlashkar', or chief of the cavalry. Lastly, 10,000 troopers formed a flying column under Jaysinghrao Dhanaji Jadhav.[28]

After three failed attempts to conquer Jinji, it was captured only after seven years on 8 January 1698. Rajaram, however, successfully escaped due to intervention of the Shirke family who hid him in the Mughal camp itself and then furnished him with horses to travel first to Vellore and later to Vishalgad.[29]

Santaji and Dhanaji

Early in their career Dhanaji and Santaji inflicted a severe defeat upon Sharza Khan, alias Rustam Khan, who was responsible for the death of Sarsenapati Hambirrao Mohite as he was coming to capture the fort of Satara in May 1690. During that period when Jinji remained unconquered, "the intrepid Maratha commanders, Santaji Ghorpade and Dhanaji Jadhav, wrought havoc in the Karnataka and Maharashtra by defeating the Mughal generals and cutting off their lines of communication."[30]

Santaji Ghorpade captured and held to ransom Ismail Khan, Rustam (Sharza) Khan, Ali Mardan Khan, and Jannisar Khan. According to the Khafi Khan, so great was the terror of his name “that there was no imperial Mughal Amir bold enough to resist him and every loss he inflicted made the imperial Mughal forces quake". Aurangzeb was at his wits’ end and admitted in public that "The creature could do nothing, for everything was in the hands of God".[31] The Mughals looked upon Dhanaji Jadhav with such awe that Mughal troops used to ask their horses, when they refused to drink, whether they had seen Dhanaji's reflection in the water.[32]

Rajaram had occupied the fort at Jinji from 11 November 1689, but left before it fell in 1698. Rajaram then set up his court at fort Satara.

In this while Rajaram set his objectives on rallying the Maratha army to drive out the Mughal invaders. The Chitnis Bakhar records Rajaram as saying: "Time and again we have grappled with the Mughal armies. The Emperor is camped at Aurangabad, in our homeland, and there I intend to lead the attack in person; bring home to the Emperor that the army that Shivaji built still exists and that Rajaram is a part of it. Prove to him that the Maratha spirit is not extinct".[33]

A letter of 22 March 1690, composed by Rajaram and drafted by Khando Ballal Chitnis to Baji Sarjerao Jedhe Deshmukh of Kari speaks of the rallying of the Vijaynagar Poligars of the South to the Maratha banner in these terms and the role of Santaji Ghorpade and Dhanaji Jadhav leading them: “We have enlisted on arrival in the Karnatak forty thousand cavalry and a lakh and a quarter of infantry. The local Palegars and fighting elements are fast rallying to the Maratha Standard. Our Raj now has a peculiar message for the people, and you as one of them already suffer the agonies of the wrongs inflicted upon it by the Mughals. You must now put forth the sacrifice required on behalf of our religion. We have dispatched Keshav Trimal Pingale to Maharashtra with a treasure of a lakh of Hons, guarded by an escort of forty thousand armed men with Santaji and Dhanaji at their head. As soon as this party arrives in your part of the country, you must join it with your following with the utmost expedition, in order to overcome the common enemy. In fact the enemy is nothing of himself : it is people like you who have raised him into that importance. If our Marathas had not joined him, he would have been nowhere. You alone possess the nerve to overcome this Aurangzeb. He has wronged you by threatening to convert you to his religion. He has already converted Netaji and Sabaji Ghatge and Janojiraje, in addition to several Brahmans also. He also entertains further deep-rooted motives of a sinister nature against our nation, of which you must beware. The Nimbalkars and the Manes have already deserted him and his ranks are being rapidly thinned. God is helping us. We are sure to succeed.”[34][35]

In 1691, as a direct taunt to Mughal encroachment in the Deccan and to show off the undaunted morale of the Marathas, Rajaram issued contemptible bounties which were deliberately exiguous to his generals for capturing Mughal cities. One such challenge was as follows: "Having clearly grasped your readiness to quit the Mughal service and return to the Chhatrapati's for defending the Maharashtra Dharma, we are assigning to you for your own personal expenses and those of your troops, an annuity...". Hanmantrao Ghorpade was entitled to receive, 62,500 hons after the capture of Raigad, 62,500 hons after the capture of Bijapur, 62,500 hons after the capture of Bhaganagar, 62,500 hons after the capture of Aurangabad, and 2,50,000 hons after the capture of Delhi itself. Similarly, Krishnaji Ghorpade was entitled to receive 12,500 hons after the conquest of Raigad territory, 12,500 hons after the conquest of Bijapur, 12,500 hons after the conquest of Bhaganagar, 12,500 hons after the conquest of Aurangabad and 50,000 hons after the conquest of Delhi.[36][37][38][39]

These aims included even the conquest of Delhi, so as to make the whole Indian sub-continent safe for the Hindu religion, and no more destruction of temples and idols was to be tolerated. This statement of the Maratha Chhatrapati's aims is not confined to a few rare documents, but runs through most of the writings detailing the political transactions of the Maratha Government of that period.[40]

Animated by a desire to avenge their wrongs, the Maratha bands spread over the vast territories from Khandesh to the south coast, over Gujarat, Baglan, Gondwana, and the Karnataka, devastating Mughal stations, destroying their armies, exacting tribute, plundering Mughal treasures, animals and stocks of camp equipage.[41]

Through imminent peril Rajaram had won his goal and at Jinji had sustained that which scholars like C.A. Kincaid call, "a siege hardly shorter than that of Troy with the skill and valour and more than the fortunes of Hector".[42] Rajaram had created armies, planned campaigns, governed distant provinces. Well-nigh unbearable though his burden was, he had nobly and worthily borne it. Through an endless darkness he had kept alive the flickering flame of his country’s independence; and when Aurangzeb thought he had at last crushed him for ever, Rajaram had re-appeared in his own kingdom and had once again hurled defiance at the northern invaders.[43]

When the council for planning the next course of action opened at Satara, Hukumatpanah Ramchandrapant, supported by his lieutenants, Parashuram Trymbak and Shankar Narayan, advanced to the Chhatrapati's seat and were lauded for their administration during the exile of Rajaram. Rajaram lauded the services of the Maratha Houses of Atole, Dabhade, Pawar and Patankar and distributed to them and to others dresses of honour suited to their rank and achievements and disclosed his strategy. Rajaram meant to let Aurangzeb wear out his army besieging the Deccan forts, while he and his lieutenants invaded with large bodies of horse the Mughal territories further than they had been invaded for many years. Thus while the Mughal emperor was trying to destroy Maratha bases, the Marathas would retaliate by destroying his. Rajaram declared: "The enemy’s power is weakened, our troops no longer fear to meet the emperor’s. Our task is reaching its close. By the blessing and merit of my father, the divine Shivaji, fortune will crown our efforts with victory".[44]

Death

Rajaram led a large Maratha force to attack the Mughal city of Jalna which he successfully plundered and set on fire. Entering the Godavari valley, he plundered Paithan, Beed and other Mughal-occupied towns along the river banks. Instead of progressing further he turned back towards Sinhagad to deposit the accumulated loot when his burdened army was ambushed by Zulfikar Khan. Rajaram tried to evacuate with all speed, but could shake off the Mughal pursuit owing to the baggage. In this disastrous retreat the Rajaram's resourcefulness and courage alone saved his army. Although half dead with fatigue, Rajaram fought a continuous series of rearguard actions for fifty miles and at last brought his command, reduced but not destroyed, to the welcome shelter of Sinhgad. The hardships and exposure of the chase had aggravated a weakness of Rajaram’s lungs contracted at Jinji.[45]

After some days high fever set in with frequent hemorrhages. Knowing his end was near, Rajaram called upon his council and commanded them not to relax their efforts in the war of liberation until King Shahu had been freed and the Mughals driven from the land of the Marathas. Rajaram thus died of lung disease in 1700 at Sinhagad near Pune in Maharashtra leaving behind widows and infants. Rajaram’s funeral ceremonies were performed by Jivajiraje Bhonsle, the direct descendant of Vithoji Bhonsle, younger brother of Maloji Bhosale and Chhatrapati Shivaji’s great uncle. To keep alive Chhatrapati Rajaram's memory, Ramchandra Bavdekar built a temple to Shiva on the edge of Sinhgad fort. The temple was handsomely endowed with lands and money and may still be seen in undiminished splendour. Janakibai,[46] one of his widows, committed sati upon Rajaram's death.[47] Another widow Ambikabai who was at Vishalgad, also performed sati, but only after she heard the news of his passing three days later. Many folk tales are centered on her powers of piety.[48]

Rajaram's widow Tarabai then proclaimed her own young son, Shivaji II as the Chhatrapati Shivaji prophesied by Shivaji I destined to conquer all India from Attock to Rameshwaram, going against the popularly held notion that it was Shahu I (whose original name was Shivaji) who was to be the Shivaji prophesied about, and ruled as her son's regent. However, the release of Shahu, by the successors of Aurangzeb led to an internecine conflict between Tarabai and Shahu with the latter emerging as the successful claimant to the Maratha throne of Satara.[49][50][51] Tarabai established a separate seat at Kolhapur and installed her son as the rival Chhatrapati. She was shortly deposed by Rajasbai, the other surviving widow of Rajaram. She installed her own son by Rajaram called Sambhaji II on the Kolhapur throne. The Kolhapur line has continued to this day through natural succession and adoptions per Hindu customs.The Satara seat passed to a grandson of Rajaram called Ramaraja after he was adopted at the insistence of Tarabai, by Shahu who did not have a natural male heir. Later Tarabai disowned him saying she had presented Shahu with an imposter.[52]

Books

- Chhatrapati Rajaram Tararani (Dr. Sadashiv Shivade)

- Ranragini Tararani (Dr. Sadashiv Shivade)

- Shivacharitra Sahitya Khand 1-15

- Maharadnyi Yesubai (Dr. Sadashiv Shivade)

- Shrimant Sambhaji Maharaj Wa Rajaram Charitra (R.V. Herwadkar)

- Shivaputra Chhatrapati Rajaram (Dr. Jaysingrao Pawar)

- Marathyanche Swatantra Yudha (Dr. Jaysingrao Pawar)

- Maratheshahiche Antarang (Dr. Jaysingrao Pawar)

- Swarajya Rakshanacha Ladha (Mohan Shete, Pandurang Balakawade, Sudhir Thorat)

- Hukumatpanah Ramchandrapant Amatya Charitra (Saurabh Deshpande)

- Chhatrapati Rajaram Maharaj (Ashokrao Shinde Sarkar)

- Marathi Riyasat - Chhatrapati Rajaram Govind Sakharam Sardesai)

- Shivchhatrapatinchi Patre (Anuradha Kulkarni)

- Shiv Putra Rajaram (Dr. Pramila Jarag)

- Bhangale Swapna Maharashtra (Drama, written by Bashir Momin Kavathekar)

See also

Notes

- ↑ Sir Jadunath Sarkar (1948). Shivaji and His Times. S.C. Sarkar. p. 318.

"Rajaram, the second son of Shivaji, was born on 24 February 1670".

- ↑ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2007). The Mughul Empire, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, ISBN 81-7276-407-1, p.296

- ↑ Mehta, J. L. (2005). Advanced study in the history of modern India, 1707-1813. Slough: New Dawn Press, Inc. pp. 45–52. ISBN 9781932705546.

- ↑ Mehta, J. L. (2005). Advanced study in the history of modern India, 1707-1813. Slough: New Dawn Press, Inc. p. 51. ISBN 9781932705546.

- ↑ "The Marathas: Chatrapati Rajaram Maharaj".

- ↑ PAWAR, Dr JAYSINGRAO (1 March 2018). MARATHYANCHE SWATANTRA YUDHA (in Marathi). Mehta Publishing House. ISBN 978-93-87789-22-7.

- ↑ Chatterjee, Indrani; Guha, Sumit (2000). Pati, Biswamoy (ed.). Issues in modern Indian history : for Sumit Sarkar. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. pp. 29–30. ISBN 9788171546589.

- ↑ A history of the Maratha people Vol. II, CA Kincaid and DB Parasnis, pg. 64

- ↑ New History of the Marathas Volume I, GS Sardesai, pg. 319-320

- ↑ A history of the Maratha people Vol. II, CA Kincaid and DB Parasnis, pg. 64

- ↑ A history of the Maratha people Vol. II, CA Kincaid and DB Parasnis, pg. 64

- ↑ A history of the Maratha people Vol. II, CA Kincaid and DB Parasnis, pg. 64

- ↑ Shivaji The Great Vol. IV by Dr Balkrishna, pg. 24-25

- ↑ A history of the Maratha people Vol. II, CA Kincaid and DB Parasnis, pg. 64

- ↑ New History Of The Marathas Vol.I, GS Sardesai, pg. 343

- ↑ New History Of The Marathas Vol.1 by GS Sardesai, pg 321

- ↑ New History Of The Marathas Vol.1 by GS Sardesai, pg 321

- ↑ जिंजीचा प्रवास, VS Bendrey, pg. 15

- ↑ A history of the Maratha people Vol. II by CA Kincaid and DB Parasnis, pg. 67-68

- ↑ A history of the Maratha people, CA Kincaid and DB Parasnis, pg. 68-69

- ↑ The Quarterly Review of Historical Studies Volumes 33-34 1993

- ↑ The Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society Volume 92, pg 100

- ↑ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2007). The Mughul Empire, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, ISBN 81-7276-407-1, p.609

- ↑ The Main Currents Of Maratha History(1933) by G. S. Sardesai, pg. 91-93

- ↑ New History Of The Marathas Vol. I, by GS Sardesai pg. 328-329

- ↑ The Main Currents Of Maratha History(1933) by G. S. Sardesai, pg. 91-93

- ↑ The Main Currents Of Maratha History(1933) by G. S. Sardesai, pg. 91-93

- ↑ A History of the Maratha People Vol II, CA Kincaid and DB Parasnis, pg 83

- ↑ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2007). The Mughul Empire, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, ISBN 81-7276-407-1, pp.294-5

- ↑ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 200–201. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- ↑ A history of the Maratha people, CA Kincaid and DB Parasnis, pg. 82

- ↑ New History Of The Marathas Vol. I, by GS Sardesai pg. 327

- ↑ Chhatrapatis Of Kolhapur by M. Malgonkar, pg 36

- ↑ New History Of The Marathas Vol. I, by GS Sardesai pg. 328-329

- ↑ Shivaji, the Great Maratha Volume 4 by H. S. Sardesai, page 956

- ↑ New History Of The Marathas Vol. I, by GS Sardesai pg. 327-328

- ↑ शिवचरित्र साहित्य खंड ५, 10-12

- ↑ The Mughal-Maratha Relations, 1682-1707 by G. T. Kulkarni, pg. 151

- ↑ Journal of Indian History Volumes 29-30 1952, pg. 84

- ↑ New History Of The Marathas Vol. I, by GS Sardesai pg. 328-329

- ↑ New History Of The Marathas Vol. I, by GS Sardesai pg. 328-329

- ↑ A History of the Maratha people, CA Kincaid and DB Parasnis, pg. 95-96

- ↑ A History of the Maratha people, CA Kincaid and DB Parasnis, pg. 95-96

- ↑ A History of the Maratha people, CA Kincaid and DB Parasnis, pg. 95-96

- ↑ A History of the Maratha People Vol. II, CA Kincaid and DB Parasnis, pg. 103-104

- ↑ Gokhale, Kamal. Rajaram Chhatrapati in Marathi Vishwakosh. Wai, Maharashtra India: Marathi Vishwakosh.

- ↑ Feldhaus, Anne, ed. (1996). Images of women in Maharashtrian literature and religion. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0791428375.

- ↑ A History of the Maratha People Vol. II, CA Kincaid and DB Parasnis, pg. 103-104

- ↑ mehta, JL (1981). Advanced study in the history of medieval India. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 562. ISBN 978-81-207-1015-3.

- ↑ Cox, Edmund Charles. A short history of the Bombay Presidency. Thacker, 1887, pages 126-129.

- ↑ Thompson, Edward; Garratt, G.T. (1999). History of British rule in India. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers. p. 56. ISBN 81-7156-803-3.

- ↑ V.S. Kadam, 1993. Maratha Confederacy: A Study in its Origin and Development. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, New Delhi.

References

- Kincaid, Charles Augustus; Parasnis, Rao Bahadur Dattatraya Balavant (1922). A history of the Maratha people. London, Milford.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 2, p. 440.