| Brent | |

|---|---|

River Brent at Brentford | |

| Location | |

| Country | England |

| Counties | Greater London |

| Districts / Boroughs | London Borough of Barnet, London Borough of Brent, London Borough of Ealing, London Borough of Hounslow |

| Towns | Hendon, Neasden, Perivale, Greenford, Hanwell |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | London Borough of Barnet, Greater London |

| Mouth | River Thames |

• location | Brentford, Greater London |

| Length | 29 km (18 mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Costons Lane, Greenford |

| • average | 1.32 m3/s (47 cu ft/s) |

| • minimum | 0.19 m3/s (6.7 cu ft/s)3 August 1995 |

| • maximum | 42.9 m3/s (1,510 cu ft/s)12 October 1993 |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Monks Park |

| • average | 1.00 m3/s (35 cu ft/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Brent Cross |

| • average | 0.34 m3/s (12 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Dollis Brook, Decoy Brook, Clitterhouse Brook, Silk Stream, Wealdstone Brook, Gadder brook |

| • right | Mutton Brook, Peggy Back's (subterranean) drain |

The River Brent is a river in west and northwest London, England, and a tributary of the River Thames. 17.9 miles (28.8 km) in length, it rises in the Borough of Barnet and flows in a generally south-west direction before joining the Tideway stretch of the Thames at Brentford.[1]

Hydronymy and etymology

A letter from the Bishop of London in 705 suggesting a meeting at Breġuntford, now Brentford, is the earliest record of this place and probably therefore that of the river, suggesting that the name may be related to the Celtic *brigant- meaning "high" or "elevated", perhaps linked to the goddess Brigantia.[2]

Topography, geology and evolution of the Brent catchment area

(For the purposes of this section, the Brent catchment area is taken to include the catchment areas of all its tributaries.)

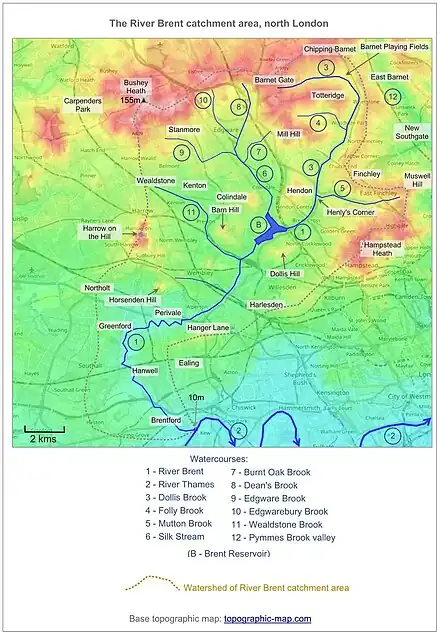

The catchment area varies in altitude from just over 150 metres above sea level at Bushey Heath, on its northern watershed, to barely 10 metres at the confluence of the Brent with the Thames at Brentford.

Broadly speaking, the catchment area can be divided into three topographical zones:

- a southern zone, lying south of a line from about Harlesden to Northolt, which is of low relief and which (apart from the hill at Hanger Lane) lies below an altitude of 40 metres;

- a basin-like north-western zone which is surrounded by areas of higher ground which rise fairly steeply to the west (Harrow on the Hill), north (Bushy Heath) and east (Mill Hill), and where several isolated hills such as Horsenden Hill, Barn Hill and Dollis Hill are located; and

- a north-eastern zone consisting of the relatively narrow and steep-sided valleys of the Dollis Brook, Folly Brook and Mutton Brook; and of the high ground which surrounds those valleys (at Hampstead Heath, Whetstone, Totteridge, Chipping Barnet, etc).

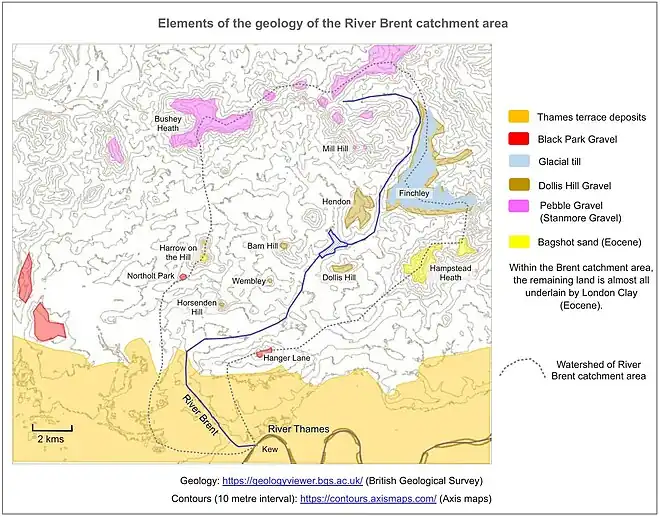

The oldest and most extensive geological formation in the Brent catchment area, as in much of the London Basin, is Eocene London Clay. This is mostly a stiff blue-brown clay, over 100 metres thick. In some higher parts of the area, a relatively thin, upper part of the London Clay formation, sandier in content and known as the Claygate Beds, is also found.

In some areas of relatively limited extent, such as on the higher parts of Harrow on the Hill, Hampstead and Highgate, the London Clay and Claygate Beds are overlain by sandy Eocene Bagshot Beds.

All these formations are overlain in several areas by much younger, Pleistocene formations, principally fluvial deposits and glacial deposits. The oldest Pleistocene deposit, Pebble Gravel, is found across the upper, northern margin of the catchment area, from Bushey Heath to Chipping Barnet. The most recent Pleistocene deposits include the post-Anglian river terrace deposits of the Thames and Brent rivers in Ealing and other southern parts of the catchment area. Glacial till is found in the north-eastern sector of the catchment area, around Finchley.[3]

Current topography is largely the result of landform evolution during the Pleistocene epoch (that is, during the last two million years or so).

Although a tributary of the River Thames, the Brent is much younger in age. An Ancestral Thames is thought to have come into being over 60 million years ago, during the post-Cretaceous uplift of Britain (an uplift which was tilted to the south-east). [4] The Brent, as a southward-flowing, left-bank tributary of the Thames, was formed as a result of the Anglian glaciation, which occurred about 450,000 years ago.

The area prior to the Anglian glaciation

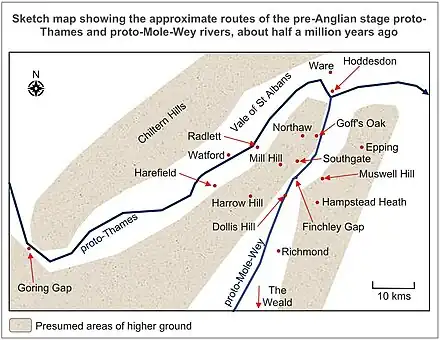

In the early twentieth century, it was suggested that the River Thames, after descending through Oxfordshire, entering the London Basin near the Goring Gap and running north-east from there, continued in that direction prior to the ice advance, past Watford and along the line of the Vale of St Albans.[5] This hypothesis has since been confirmed by much subsequent research.[6]

That "proto-Thames" river received tributaries from the south.[7] At least one of those tributaries traversed what is today a dissected plateau which lies to the south-east of the Vale of St Albans. This plateau stretches from Bushey Heath to Northaw and beyond, and is capped over wide areas, at altitudes ranging from about 150 metres to 130 metres, by a fairly thin (average 3 metres) layer of sand and gravel known as Pebble Gravel (or, in places, Stanmore Gravel).[8]

Although flint is the main component of this gravel, it has been known since the late nineteenth century that it also contains in places a notable quantity of chert derived from Lower Greensand Beds in the Weald. It was suggested early on that this "pointed to the former existence of streams from that area".[9]

S.W. Wooldridge later suggested that it was in fact "a river of major dimensions" (which) "entered from the south" that was responsible for transporting much of this chert to areas which are now north of the River Thames.[10] It was clear from the broad course which Wooldridge plotted for this river that it was an ancestor of the River Mole (and/or River Wey).

In 1994, D.R. Bridgland proposed that Pebble Gravel (or Stanmore Gravel) which is located on Harrow Weald Common (near Bushey Heath) was deposited by an ancestral Mole-Wey, and that that river was a tributary of the River Thames at a time when the latter river was flowing to the north-west of the Vale of St Albans. That could have been nearly two million years ago. He also suggested that similar gravel, located further north-east near Northaw at a slightly lower altitude, was also deposited by an ancestral Mole-Wey, but at a later date (which could have been around 1.75 million years ago).[11]

At those times, the topography of the country in what is today the Brent catchment area would have been very different from today's topography, because the Pebble Gravel was laid down on a valley floor, whereas today it occupies the highest ground in the area. The relief has thus been inverted.

But, in 1979, P.L. Gibbard mapped younger deposits, known as Dollis Hill Gravel and named after one of the locations where this deposit is found, which were also laid down by an ancestral Mole-Wey river.[12][13] (This river is also referred to in places as the "proto-Mole-Wey".)[14][15] These deposits are found at what is today the so-called Finchley Gap, and to the north-east and south-west of it. Dollis Hill Gravel is found, for example, south-west of the Gap at Hendon and Horsenden Hill, and north-east of the Gap over wide areas from Southgate to Goff's Oak.[16]

Today, the highest of those deposits rest at an altitude of around 100 metres (for example at Muswell Hill). So the proto-Mole-Wey valley around Finchley, in the sense of being an area of lower ground lying between higher ground on either side (for example, at Mill Hill and Hampstead Heath, both at altitudes of over 120 metres today), must have existed by the time those highest deposits of Dollis Hill Gravel were laid down. That could have been around one million years ago.[17]

The proto-Mole-Wey river which laid down the Dollis Hill Gravel thus flowed along a line broadly similar to that of today's River Brent, but in the opposite direction, from south-west to north-east. The gradient of the floor of that valley in the area now occupied by the Brent catchment was low - probably no more than 50 cm per kilometre.[18]

Tributaries of the proto-Mole-Wey river

The number, and courses, of the tributary streams which flowed into the proto-Mole-Wey river prior to the Anglian glaciation, in the area currently covered by the Brent catchment area, are not known with any certainty. But it is known that, elsewhere, some tributaries of rivers which were themselves severely disrupted by that glaciation today still follow broadly the same lines as their pre-glaciation valleys. This is the case, for example, for certain tributaries of the upper River Lea, such as the Rivers Mimram and Stort.[19]

So it seems reasonable to suggest that parts at least of the network of tributary streams which flowed into the proto-Mole-Wey river, in the area currently covered by the Brent catchment area, proved to be equally robust. Thus, it is possible that, although the proto-Mole-Wey river itself was completely replaced by the River Brent during the Anglian glaciation, and parts of those of its tributaries which came into contact with the ice front were diverted (as described below), other sections of today's network of Brent tributaries broadly reflect parts of the pre-Anglian network of tributary streams which fed the proto-Mole-Wey. This could apply to, for example, the upper part of the Dollis Brook, the Folly Brook, the Silk Stream and the Wealdstone Brook.

In the case of the uppermost section of the Dollis Brook, which runs broadly west-east from Barnet Gate towards Barnet Playing Fields, it is possible that, immediately prior to the Anglian glaciation, that stream continued eastwards (where it now turns southwards, for reasons explained in the next section), at a today's altitude of about 90 metres, and joined a precursor of the Pymmes Brook in the vicinity of East Barnet. That precursor brook may then have flowed south-eastwards to join the proto-Mole-Wey somewhere around New Southgate.

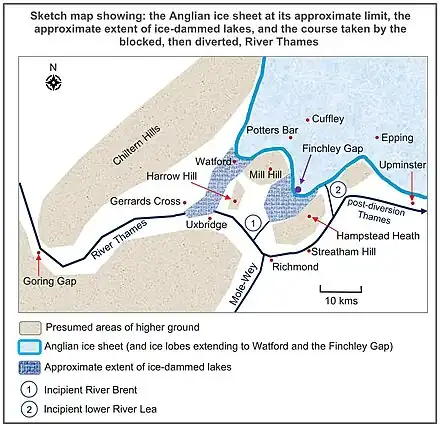

The Anglian glaciation

It has been known since the nineteenth century that an ice sheet once descended from the north of England as far as north London and left behind extensive spreads of till and other glacial deposits. This ice advance has since been identified as the Anglian glaciation. After reaching as far south as Ware, about 450,000 years ago, lobes of this ice sheet extended up two valleys, oriented south-west to north-east - that of the proto-Thames (which, by this time was flowing along the line of the Vale of St Albans, and where an ice lobe extended to Watford), and that of the proto-Mole-Wey (where the other lobe extended to Finchley).[20]

In the early twentieth century it was concluded that the Thames must have been diverted to its more southerly course of today by the ice advance up the Vale of St Albans to Watford.[21]

As noted above, the proto-Mole-Wey river was a tributary of the proto-Thames. It flowed northwards from the Weald, then passed through what is today the Brent catchment area (but in the opposite direction to the flow of today's River Brent).

As an ice sheet lobe advanced up the proto-Thames valley towards Watford, the passage of the river was blocked, and its water backed up to form a lake in front of the advancing ice.[22][14] That lake eventually extended as far up the proto-Thames valley as a point south of Gerrards Cross, where lacustrine deposits have been identified.[23]

The water in that lake eventually rose to relatively low points on the interfluve with the proto-Mole-Wey catchment area to the south-east, where that water could overflow into that catchment area. Two such points were at Carpenders Park and Uxbridge.[24][12]

Water overflowed into the proto-Mole-Wey catchment in a considerable volume and with considerable force (to the extent that, in the case of the overflow at Uxbridge, the Thames in due course established a completely new course through that route).[12]

In the case of the overflow through the Carpenders Park gap (today followed by the West Coast Main (railway) Line between London Euston and Watford), the Thames overspill surged through Wealdstone and Kenton. The land it crossed would have been bare of vegetation and very susceptible to fluvial erosion. The powerful overflow quickly eroded areas of higher ground. This could have included a possible ridge of higher ground running from Stanmore to Colindale (separating ancestral valleys of the Wealdstone Brook and Silk Stream), similar to and parallel with the ridge that still exists and that runs from Barnet Gate to Mill Hill.[25] The overflow thus carved out much of the London Clay basin which today forms the north-western section of the River Brent catchment area. In particular, it probably removed much of the Dollis Hill Gravel which must have been situated in this area prior to the Anglian glaciation. [26]

At the same time, a lake formed in front of the ice lobe which was moving south-westwards up the proto-Mole-Wey valley towards Finchley, and which was blocking the flow of the proto-Mole-Wey river.[12] The swirling waters of that lake also caused considerable erosion of the previous topography. But isolated islands, mostly capped by Dollis Hill Gravel, were left within the lake.

The Thames eventually established a diverted course from Uxbridge to Richmond, from where it continued, in a broadly eastwards direction, towards the North Sea.[27] This caused the lake in the proto-Mole-Wey valley to be drained, thus leaving the former islands in the lake as isolated hills in what is now the London Clay basin of the north-western section of the River Brent catchment area.[28]

The birth of the river Brent

As illustrated on a geological map of the area, it is striking that Dollis Brook, for the greater part of its length between Barnet Playing Fields and Henly's Corner, follows a north-south line close to the western limit of glacial till left by the ice sheet lobe which extended to Finchley.[29]

Similarly, Mutton Brook follows an east-west line which is close to the southern limit of glacial till left by the ice sheet lobe.

This is because, as the ice sheet lobe in the valley of the proto-Mole-Wey river moved up that valley, it would have blocked streams flowing down towards that river from higher ground to the west and south. In particular, it would have forced the eastward-flowing Dollis Brook to have turned to the south, alongside the western edge of the ice lobe (and likewise for Folly Brook). And it would have forced northward-flowing drainage coming down from Highgate and Hampstead to have turned to the west, alongside the southern edge of the ice lobe (thus forming Mutton Brook).

Fed by meltwater from the adjacent ice sheet, these streams would have cut down quickly along their new routes. And later, when the ice sheet retreated, a substantial thickness of till was left behind where the ice once sat. (For example, in the locality of the Finchley Gap, the ice left glacial deposits which today are up to 18 metres in thickness.[12]) Consequently, after the ice retreated, the two streams continued along the same courses that they had been forced to follow by the ice lobe - between glacial till and the higher ground of Mill Hill, etc in the case of Dollis Brook, and between glacial till and Hampstead Heath, etc in the case of Mutton Brook.

At the time of the ice lobe, those two streams would at first have flowed into the pro-glacial lake in the proto-Mole-Wey valley which is referred to above.

But then the River Thames established its newly-diverted course. That course appears to have run along a line approximately from Uxbridge to Northolt Park, Perivale, Richmond and Streatham Hill.[30]The newly-diverted Thames thus cut across the floor of the proto-Mole-Wey valley. And being a very powerful river, it would also have cut down below the level of that valley floor to some extent. Water from the Finchley pro-glacial lake would thus have flowed down into the Thames and would have been carried away by it. As mentioned earlier, the lake would thus have dried up.

A stream would then have cut back from the Thames, probably from around Hanger Lane. That stream probably cut back in a north-easterly direction along the line of the former proto-Mole-Wey valley bottom (the near-flat surface of which would by then have been covered by a certain amount of glaciofluvial material deposited by meltwater flowing from the front of the ice lobe). That stream, which would quickly have cut back to the ice front at Henly's Corner, would have been the incipient River Brent. Dollis Brook and Mutton Brook would have there flowed into this new stream. And the new stream would have been joined on its right bank by former tributaries of the proto-Mole-Wey river, notably the Wealdstone Brook and the Silk Stream.

As the ice sheet melted, that incipient River Brent would have been heavily loaded with glaciofluvial material flowing from the melting ice, and from the till which the ice sheet was leaving behind. It appears that, at Hanger Lane, near its initial confluence with the Thames, the Brent was forced to deposit a large quantity of that material.[31] In doing so it may also have been forced to move to its current course, slightly to the north, with its junction with the Thames thus moving to the west, in the vicinity of Greenford.

Thus, by end of the Anglian stage, the current drainage network in the Brent catchment area had broadly been established.[32][33] But the rivers and streams in the network at that time would then have been flowing at a higher level, relative to their altitudes today. On average, this could have been around 20-30 metres higher.

post-Anglian landscape evolution

In the 400,000 years which followed the Anglian stage, rivers and streams incised themselves more deeply into the underlying strata. That erosion mostly took place in periods of "high discharge, under cold climatic conditions" when river flow was augmented and when vegetation was thin.[34]

In particular, the River Thames, which, in the vicinity of Hanger Lane was at a today's altitude of around 70 metres when it first established its diverted course, had probably cut down to about 60 metres by the end of the Anglian stage,[35] and is now at an altitude of barely 10 metres at Kew.

In thus cutting down by about 50 metres since the Anglian stage, the Thames would thus have lowered the base level of rivers and streams in the Brent catchment area, and they too have cut down to a notable degree in places, even though they obviously had much less erosive power than the much-larger Thames. For example, the junction of Dollis Brook and Mutton Brook today is at an altitude of just under 50 metres. When the proto-Mole-Wey river was flowing through this locality prior to the Anglian glaciation, it was at an altitude of 68 metres.[36]

And Dollis Brook is relatively steep-sided in certain sections - for example, around Woodside Park, where the ground falls from over 90 metres altitude on the Finchley High Road to the brook at barely 60 metres, in a distance of only about one kilometre. A sizable section of that slope would have been the result of fluvial incision since the Anglian stage.

During its post-Anglian incision, the Thames in this area moved in a southward direction. As it did so, it laid down river terrace deposits (mostly sand and gravel) of decreasing age and altitude. The Thames-Brent confluence also moved to the south, with the River Brent thus extending its course by over five kilometres, from Greenford to Hanwell, then to Brentford. As the Brent moved southwards, it cut down through the river terrace deposits which had been laid down by the Thames.

During the post-Anglian period, the River Brent itself left river terrace deposits in places. An older one is a Boyn Hill deposit just north of Brent Reservoir at an altitude of 60 metres.[37] Younger ones include almost continual stretches of Taplow and Kempton Park deposits in the valley bottom and adjacent slopes downstream of Brent Reservoir.[38][39]

Thin strips of alluvium, immediately adjacent to the River Brent, Wealdstone Brook, Silk Stream and Dollis Brook, have been deposited in very recent geological times. They extend throughout almost the whole length of those watercourses.

During the long, cold periods of the last 400,000 years, when there were an arctic climate and a lack of vegetation, "periglacial solifluction has been the most potent agent of erosion in the district ... when snow melted in the spring, debris of frost-weathered material formed a slurry, which gradually flowed downhill".[40] This process has caused a general lowering of the surface over much of the Brent catchment, particularly perhaps in the London Clay basin of the north-western sector of the catchment, such as in the Kenton area. It has also probably accentuated the isolation of the isolated hills in that sector, and led to a diminution in their size. This is illustrated in both senses by the current aspect of Horsenden Hill, whose minuscule Dollis Hill Gravel cap is nearly three kilomètres distant from its nearest neighbour at Wembley (Linden Avenue).[41]

Wind erosion has also been a factor, especially, it seems, in fairly recent very cold periods (of the late Devensian). Wind-blown deposits form part of the "brickearth" (or "Langley Silt") deposits which overlie parts of the Thames terrace deposits.[42][43]

Human history

Pre-Roman to Norman history

So extensive have the changes to this landscape been that what little evidence there is of man's presence before the ice came has inevitably shown signs of transportation here by water and reveals nothing specifically local. Likewise, later evidence of occupation, even since the arrival of the Romans, may lie next to the original banks of the Brent but have been buried under centuries of silt.[44]

The most prominent pre-Roman settlement on the River Brent was apparently at Brentford. This Bronze Age site pre-dates the Roman occupation of Britain, and thus predates the founding of London itself. Many pre-Roman artifacts have been excavated in and around the area in Brentford known as 'Old England'. The quality and quantity of the artefacts suggests that Brentford was a meeting point for pre-Roman tribes. One well-known Iron Age piece from about 100 BC to AD 50 is the Brentford horncap[45] - a ceremonial chariot fitting that formed part of local antiquarian Thomas Layton's collection,[46] now held by the Museum of London. Odd Roman artifacts have also been found by the River Brent in both Brentford and Hanwell, suggesting that a trading route may have used the river to trade with the early villages in Roman and post-Roman times.

However, can the river Brent be considered a border in the sense that the quality it possessed of dividing the land was notable enough to be given such a descriptive title? The Brent river valley in 705 would have looked very different to today. Before modern day dredging, the river was wider and shallower. Before the construction of its weirs, the Brent reservoir and Grand Union Canal (and its Paddington Branch, which takes much of the Brent's waters) the river would have flooded more frequently than it does today. The alluvial valley floor would therefore have been swamp. On Google Earth, the signs of many of the old drainage channels that turned the marsh into water meadow are still visible. Bordering these marshes would have been dense thickets of thorn and willow. A link can be made with the local area, the south-west plains of Middlesex, forming the Anglo-Saxon founded Hundreds of Elthorne [shelter tree, from Helethorne with the 'h' being lost to elision], and Spelthorne (perhaps speech/discourse tree).

The earliest surviving reference to the then village of Hanwell is in 959, when it is recorded as Hanewelle in pledge, when Alfwyn (a Saxon) pawned his land for money to go on a pilgrimage.[47] It was only a small hamlet on the river banks in the 10th century.

Another conjecture is that one of the possible etymologies given for this ancient parish of Hanwell is 'Han' as Saxon for boundary stone and 'well' as Saxon for fresh water or spring. The Rectory Cottage to the parish church of St Mary has a large stone of about a ton in its garden. A large land owner and historian also put forward the observation that this appeared to line up with what he maintained as traces of the parish being divided up into the Roman centuria unit of land area, indicating that they used this stone as a datum. However, the position of the field boundaries and roads still wait to be statistically analysed to test this hypothesis.

Nevertheless, a cursory inspection of old Ordnance Survey maps, blended with an appreciation of how hedges and boundary paths drift with time and use, strongly suggests that they approximated to dimensions of the quintarial limes of the Roman field system by a degree that far exceeds what would be expected by chance alone. Hanwell parish was very narrow in the east–west direction. The letter of 705 calling a meeting at Brentford to resolve a dispute between the East Saxons and the West Saxons; as early as this the Brent was recognised as a convenient halfway point or boundary. Other later historically important meetings are also recorded here.

Going back a little further, etymological evidence of the West Saxons renaming settlements to the west including the Chilterns to the north west can be seen in their many place name endings such as field, ham, ton, and worth but at the Brent they almost stop — the course of the river presenting a boundary between lands named by the invading Saxons to the west and lands retaining the last vestiges of Romano-British London which lasted until the end of the 5th century, having in many cases, older names.[45]

Evidence of Roman settlement, that was discovered by the Hendon and District Archaeological Society and others exists in an urn burial of a headless child was found in nearby Sunny Hill Park. Hendon manor is described in Domesday (1087), but the Anglo-Saxon name [æt þǣm] hēam dūne meaning '[at the] high hill', is earlier.

Post-Norman history

The course of the river has demarcated sub-tribal then administrative divisions. It marked the boundary of Middlesex and Hertfordshire and at a lower, less important level, Gore Hundred and the Liberty of St Albans (also known as the Hundred of Cashio).[48]

By the Middle Ages malaria had reached Britain: locally endemic in the south. The main instances were among shepherds (shearing marsh wool) and fishermen along the Thames as well as at Romney Marsh, following which the major lower Thames tributaries may have been seen for a time as unhealthy for settlement on their immediate banks; many adages of marsh and bog may date to this period. At places where river gravel beds formed a firm river bed fording was safe. Some such fording places were the Roman road crossing in Brentford itself, elevated to the status of a bridge in medieval times, in part funded by a small tax on Jews crossing the bridge, Green Lanes in Hanwell (a reminder that this was an old droving route, the word 'green' signifying that livestock could graze whilst on their last journey), and Hanwell Bridge on the Uxbridge Road. With only a few fordable places along the river's course, this presented an ideal natural defensive barrier.

The original parish of Hanwell took in Boston Manor and Brentford, running three and a half miles north from the river's discharge but about one seventh the width. It separated the curacy of Norwood Green (west) and Ealing (specifically Gunnersbury manor) east. To the north it bordered Greenford and Perivale also using the river. Hanwell is only just over 3,000 ft (900 m) wide along the east–west line of the Uxbridge Road. The river's line, before the draining of the marshes, formed a natural boundary between the different pre- and post-Roman tribes of the south-east of England.

Certain accounts of the Romantic Period have speculation from its propensity to suggest regular links to druids, or of some other ancient religious deity, all which alluded more to fancy with which to delight the readers of the new vogue in travelogues, rather than the result of any serious study, the true history of the river Brent from these cannot be made out.[45]

The London Borough of Brent derived its name from the river when in 1965 the boroughs of Willesden and Wembley chose a name when uniting.[49] This is also reflected in the coat of arms of the borough, showing a stylized river in the shield.

Earliest recorded reference

Brentford was a likely site of a battle recorded by Julius Cæsar between Julius Cæsar and local king, Cassivellaunus, in 54 BC.

A letter from the Bishop of London in 705 suggesting a meeting at Breguntford, now Brentford, is the earliest record of this place and of the river.[2]

River's course

From source and Dollis Brook to Brent Reservoir

The River Brent starts as the junction of Dollis Brook and Mutton Brook close to Bridge Lane in Hendon, in the London Borough of Barnet.[1]

Its main tributary is Dollis Brook, around 6 miles (10 km) long, which rises in Moat Mount Open Space, Mill Hill, and flows eastward through fields and open space to King George V Playing Fields in Totteridge. It then turns south and passes between Totteridge and Whetstone. A tributary, Folly Brook, meets the Dollis not far from Woodside Park tube station. The Dollis then flows through Church End, Finchley, to Hendon.

Mutton Brook rises in Cherry Tree Wood, East Finchley. It flows westward, underground, until it comes to the surface shortly after The Bishop's Avenue, and then flows through parks next to Lyttelton Road, Falloden Way and North Circular Road to meet the Dollis.

A small stream called Decoy Brook rises in Turner's Wood in Hampstead Garden Suburb[50] and runs through Temple Fortune to join the Brent at Riverside Drive in Hendon.[51] Another, Clitterhouse Stream, rises at two locations on the western slopes of Hampstead Heath. One brook feeds the Leg of Mutton Pond on West Heath, and the lower duck pond of Golders Hill Park. On the bank of the stream by Leg of Mutton Pond lies the site of a Stone Age encampment, which was excavated by the Hendon and District Archaeological Society in the 1970s. Another brook feeds the upper duck pond in Golders Hill Park and then flows to merge with the other branch at the lower duck pond. From Golders Hill Park the stream flows underground approximately in parallel with Dunstan Road to Childs Hill Park. At Granville Road, at the south end of the park, a laundry industry once used the clean water of the stream as did a nursery industry, now all disappeared. From Granville Road the stream flows underground to emerge at Clitterhouse Playing Fields and joins the Brent at Brent Cross shopping centre.

The River Brent flows alongside the A406 North Circular Road through Brent Park and then under the Northern line to Brent Cross and the Brent Reservoir, where it is joined by another tributary, the Silk Stream. There are several feeders to the Silk Stream including Burnt Oak Brook, Edgware Brook and Deans Brook.[52]

From Brent Reservoir to Brentford

From here, still closely following the North Circular Road, the river passes Stonebridge Park station, where it is joined by Wembley (Rowlands) Brook, which rises in Vale farm near Sudbury.[53] The river continues under an aqueduct carrying the Paddington Arm of the Grand Union Canal. From Stonebridge Park the river turns westward, and flows under the A40 Western Avenue, past the Lilburne walk into Tokyngton Recreation Ground in Harlesden, and through the adjacent Brent River Park[54][55] for three miles until it reaches Perivale. It then runs through Perivale Park past the local running track and under the railway bridge and into Stockdove Way crossing Argyle Road at the traffic lights into Perivale Lane, where it joins up with the foot/cyclepath at St Mary's the Virgin Perivale through to Pitshanger Park.[56] The river runs through Longfield / Perivale East Meadow and Pitshanger Riverside meadows.[56]

This part of the river, as it passes through the southern boundary of Perivale Park Golf Course, is joined from the north by Costons Brook.[57] It was dredged deeper in the 1960s and a control weir built, to reduce the risk of flooding, especially of Costons Lane, along which there is a flood protection wall. Previously, Ruislip Road East would also regularly become impassable.

The river then swings south again at Greenford Bridge to Hanwell,[58] a mile away across the fields. The river runs by the local cyclepath, along the northern pavement over Greenford Bridge and into Costons Lane before turning eastwards into Perivale Park.[56]

The river continues southeastward past St. Mary's Church. It flows under the Great Western Railway at the 900-foot-long (270 m) Wharncliffe Viaduct,[58] a high spanned railway viaduct carrying the main-line railway from Paddington to the west of England.

Within about 500 m (550 yd), the River Brent is joined from the west by the main line of the Grand Union Canal at the foot of the Hanwell flight of locks, below Lock 97. From here, the Brent is canalised and navigable — the river and canal pass through Osterley Lock (98),[58] Clitheroe's Lock (99) and Brentford Gauging Locks[59] (100). It finally joins the tidal River Thames at Thames tidal locks - 101 in Old Brentford, a mile upstream of Kew Bridge.[54][60]

The river intersects with the north to south Capital Ring, Section 8, which runs alongside it from Osterley Lock to Greenford.[61]

Industrial heritage

Brentford Dock

Brentford Dock in west London was a major transshipment point between the Great Western Railway (GWR) and barges on the River Thames. The building of Brentford Dock was started in 1855[62] and it was formally opened in 1859. The dock yard was redeveloped in 1972 and is now Brentford Dock Marina and Brentford Dock Estate.[63]

Brent Reservoir

The Brent Reservoir (popularly called the Welsh Harp Reservoir) is a reservoir which straddles the boundary between the London boroughs of Brent and Barnet and is owned by British Waterways. The reservoir takes its informal name from a public house called The Welsh Harp, which stood nearby until the early 1970s.

In a recent survey, a large number fish were captured in the reservoir and adjoining parts of the River Brent and Silk Stream, 95% of which were Roach. However, fishing is prohibited in the reservoir itself.

The plans for the construction laid in 1803 were abandoned because of cost, but by 1820 there was not enough water to supply the Grand Union Canal and the Regent's Canal, so under an Act of Parliament in 1819, the Regent's Canal Company decided to dam the River Brent and create a reservoir in order to guarantee a sufficient water supply for their canals during drier weather, an accidental damming of the feeder streams and similar times of need.

The reservoir was constructed by William Hoof between 1834 and 1835. The water flooded much of Cockman's Farm, to supply the Regent's Canal at Paddington. It was called "Kingsbury Reservoir" and its 69 acres (280,000 m2) spread between Old Kingsbury Church and Edgware Road. Hoof, who was awarded the tender for the work (including the construction of a bridge) received the sum of £2,740 6s.[64] In August 1835, a few months before completion, four brothers named Sidebottom drowned in an accident.

The Welsh Harp Conservation Group (WHCG) managed in 1972 to fight off a local development plan. The WHCG organises management work, such as annual refurbishment of the tern rafts and works with Brent and Barnet councils on the site's management, including applying for National Lottery bids.[64]

Parks and nature reserves

Lower Dollis Brook SINC

Soon after its source in Hendon the river runs through Brent Park (Hendon), and the park and the first part of the river until it passes under the Northern line are part of the Lower Dollis Brook Site Borough of Importance for Nature Conservation, Grade II.[65][66][67]

Brent River Park

Brent River Park is one of London's larger urban green spaces. The natural landscape has recently been improved through the River Brent Project and further plans are proposed for future improvements. A new cycle path and wildlife conservation areas were opened in 2008.[54] The borough's riverside park land community space will have its suitability for informal ball games improved over the next few years under the River Brent Project. The spaces are also popular with local dog walkers, children people out walking and local nature lovers.[68]

The whole of Brent River Park/ River Brent Park area is now designated as a nature conservation area and was so popular it received the Mayor of London's seal of approval by winning £400,000 for park projects and improvements in 2009, through the mayoral assembly's West London Priority Parks Award.[69] The park is now full of flora and fauna, along with its adjacent meadows and colonies of bats.[70]

Perivale East Meadow and Pitshanger Riverside Meadows

The three meadows of Longfield/Perivale East Meadow and Pitshanger Riverside Meadows (part of Brent River Park) with natural riverbanks form part of the River Brent flood plain home to mallard ducks, moorhens, kingfishers and grey wagtails.[56] Herons can also be seen along the river.[71] It also passes through Perivale Park, which has had a few herons recently.[56]

Tokyngton Park

The River Brent also enters Tokyngton Park in Tokyngton, Brent.[72][73][74] The extensive flood prevention work undertaken during both the 1940s and 1970s, had led to this section of river in Tokyngton Park in Tokyngton, Brent, being straightened and enclosed in concrete. The river thus provided little or no recreational value to the local populace, whilst the quality of wildlife habitat was poor. During 1999, a local partnership was formed between the local authority, the Environment agency, local community groups and local firms, to implement improvements to the park for both people and wildlife.[72][73][74]

The park can be accessed either locally by foot or via an official urban walking route from Hanwell railway station and Brent Lodge Park; Perivale tube or most stops served by the 95 bus service. Car parking is plentiful in the streets adjacent to Hanwell railway station. To return to the start of the walk, take the 95 bus from Western Avenue to Greenford Red Lion, then the E3 bus to Hanwell railway station. Public toilets can be found in Brent Lodge Park.[70][75]

Brent Lodge Park and the Churchfields

Brent Lodge Park (or BLP) and Churchfields, which is located The Brent River Park, is a pocket of the countryside within the now urban environment of the London Borough of Ealing. the park is bordered by the River Brent on the west and south and has become one of the favourite places for locals to go for tranquillity and chilling out.[75]

The park got an EU/Department for Communities and Local Government Green Flag Award in 2009. Brent River and Canal Society with local park ranger Tony Ord look after the park.[75]

Brent Lodge Park and the Churchfields is another park along the course of the river as it passes through Ealing.[75] The park is accessible from Hanwell train station by either the E3 and E1 on bus stops on Greenford Avenue, then the 83, 92, 195, 207, 282, 427 and 607 stops on the Uxbridge Road and Ealing Hospital, or a short walk to the entrance on the land by the hospital or via West Middlesex Golf Course. Vehicular parking is limited within the car park at the end of Church Road and parking along Church Road being restricted during summer and weekends. The hospital's park is only for the hospital staff, patients and visitors to use.[75]

It contains both public toilets, a café, animal centre and Millennium maze. The extensive hay meadows and grand trees making it a great place to spot many forms of fauna and flora.[75]

Within the bounds of the site there is a grade 2 listed stable block (it contains an animal centre) which is the only remains of the old manor house, which sadly burned down in the 1930s.[75]

Wembley riverside walk

A public riverside walk (Wembley riverside walk) leads to Wembley Stadium.[68] The River Brent & Grand Union Canal Circular Tour and Ealing Cycling Campaign Routes and Rides follow part of the River Brent. Where the route follows the River Brent, it does so as closely as possible on well-made paths and roads.[76]

Notable buildings

Ealing Hospital was re-built near the banks of the River Brent in the 1970s, on the same site as St Bernard's Hospital, dating back to 1832 (as Hanwell Asylum).

Within the bounds of the site of Brent Lodge Park and the Churchfields there is a grade 2 listed stable block (it contains an animal centre) which is the only remains of the old manor house, which sadly burned down in the 1930s.[75]

Environmental issues

Pollution

River Brent was badly polluted since 1886 after contamination caused by sewage disposal outlets, rubber works and the early oil industry. The more recent rise in the rate of motor traffic has also become a major reason behind modern day, upstream pollution.

High sewerage levels had killed off the local trout at Brentford by the early 1920s. The river was cleaned out and the sewerage sent into a separate underground pipe by World War II. A few trout began to return in the 1990s.

The water quality upstream in the River Brent, and urban diffuse pollution, which has affected biological oxygen levels in Ealing [77][78] and the area in Brent is affected by diffuse urban pollution and drain misconnections as of 2010.[78][79]

The Silk Stream tributary was still the victim of at least one sewerage outflow pipe in 2010.[80]

Thames Water was called in 2010 to replace a collapsed sewer pipe in Queens Walk, Ealing but found that a stretch of town houses were in fact not properly connected to the sewerage system when they had been built in 2000; for 10 years their effluent had been carried into the River Brent. The Environment Agency's, environment management team leader, Sarah Mills, said: "Approximately eight to nine town houses have been found to be misconnected, which Thames Water have advised would have occurred when they were built around the year 2000."[81] A later, but thankfully much smaller, sewerage leak occurred nearby on 3 April 2011.[82]

Culverting and flood alleviation works

Corseting or embanking (to form dry land embankments known in the US as levees) mostly took place in the 20th century, along most of the course. The banks' width could be reduced due to water retained by the Canal Feeder. The mid-course of the river had been about 5 feet (1.5 m) deep, rising to about 14 feet (4.3 m) when it caused local flooding. Local flood alleviation work has mostly taken place from the 1940s to the 1970s, as Brent's Tokyngton Park.[72] Brentford's section has been modified, cleansed and dredged several times since the late 19th century.

The River Brent, proto-Brent River Park and surrounding area almost became a section of the Greater London Council's flood prevention scheme plans for Ealing in the 1970s. The Brent flood prevention scheme was finally completed in the 1980s.[69]

The intermittent flooding in the 1970s was causing significant damage to buildings in Greenford's Costons Lane area and roads and parkland. The then controversial proposal was to channel the Brent into a concrete trough, possibly covered with a concrete lid, some 75 ft wide. The planned scheme had allowed natural flood plains, away from housing, roads and riverside footpaths to soak up the excessive water flow to reduce the level of flooding through the passage of the flood water into the underlying ground water level.[69]

Parts of the river's course that had been buried under concrete for most of the 20th century were planned to be uncovered to revitalise the area in 2008.[49]

Environmental regeneration

The Brent River and Canal Society (BRCS)

The Brent River and Canal Society (BRCS) volunteer group was founded in 1972 by several Hanwell residents, led by Luke Fitzherbert, under the umbrella of Hanwell Preservation Society, had taken the initiative to clear the river of two years' worth of dumped rubbish.[69]

The society went on to campaign vigorously in the 1970s for the creation of Brent River Park, which was set up in 1975, saving it from use in Greater London Council's flood alleviation scheme plans for the London Borough of Ealing at the time. There were mostly plans to resolve extensive flooding which occurred periodically in the Perivale and Ealing areas. The Brent flood alleviation scheme was finally completed in the 1980s. Ultimately, this helped to achieve the Brent River and Canal Society objectives of a continuous urban walk along the river's course from Hanger Lane to Brentford. The first was Fitzherbert Walk, which passes over the river from Hanwell Bridge on the Uxbridge Road to where the river joins the Grand Union Canal opened in 1983 and was named after Luke Fitzherbert. A new footpath underneath the Wharncliffe Viaduct in Hanwell was opened in 1985 and is now part of the National Footpaths recognised walk, the Capital Ring.[69]

Local community projects

There was a litter removal operation on the 19 and 20 August 2010, in Brent Lodge Park, Hanwell. Volunteers cleared up litter from river and banks to help improve the area for residents and wildlife. The clean-up was to be followed by some family fun activities from 1pm-5pm, including river dipping and refreshments.[83]

School children from Alperton Community School were also involved in an Active Citizen Scheme along with the Environment Agency, to remind people not to pollute the Wealdstone Brook and River Brent through the abuse of the street surface water drains[84] who conclude that littering, old plumbing and disposing of waste such as engine oil are destroying local fish spawning grounds.[84]

February 2011 saw several community projects launched to clean up the River Brent to reduce the risk of damage to local fish spawning grounds.[85]

River Brent Project regeneration scheme

The River Brent Project regeneration scheme is aimed at improving the local environment, wild live habitat and flood prevention.[49][86][87]

| Project location[49][73] | Main project goal[49][73] |

|---|---|

| Boston Manor | biodiversity |

| Hanwell meander | fishery |

| Greenford | flood prevention |

| Brent Loge Park | urban renewal |

| Tokyngton Park | urban renewal |

| Wemberley industrial estate | global warming |

| Kingsbury Park | biodiversity |

| Gadder brook | habitat |

| Brent Cross | global warming |

| Brent Reservoir waterscape and reed bed | habitat |

| Golders’ Green | drainage diversion. |

| River Brent Business Park | drainage diversion |

| Silk stream's toe board | biodiversity |

| Wealdstone brook | urban renewal |

| Edgware brook | biodiversity |

| Barnet | industrial drainage diversion |

| Edgware Park FSA | flood prevention |

| Mill Hill | domestic sewage and drainage diversion |

| Burry Farm FSA | flood prevention |

| Belvedere Way, Kenton | culvert uncovered |

Work at Tokyngton Park, Brent

The extensive flood prevention work undertaken during both the 1940s and 1970s had led to this section of river in Tokyngton Park in Tokyngton, Brent, being straightened and enclosed in concrete. The river thus provided little or no recreational value to the local populace, whilst the quality of wildlife habitat was poor. During 1999, a local partnership was formed between the local authority, the Environment agency, local community groups and local firms, to implement improvements to the park for both people and wildlife.[72][73][74]

It was hoped that this provides a new lease of life for the river and enhances the quality of the local environment by removing the river from its concrete banks and to create an attractive public open space. The existing concrete river channelling and casing would be removed and the river's course modified to create new meanders in the middle area of the 'River Park' zone. The removal of some existing paths and provide new and the provision some new street furniture and a fixed fibre glass gazebo would also occur if further plans go forth.[72][73] It will also try to emphasise on community participation in the local project.[74]

The Brent Cross Cricklewood development

Under plans for the Brent Cross Cricklewood development, the River Brent, which is currently (as of May 2011) in a 40-year-old concrete channel, and its tributary Clitterhouse Stream will be realigned and restored to a more natural state, incorporating a wetland environmental area and a public riverside walkway. Flood risk is to be reduced by restoring the flood plain and the addition of sustainable drainage, such as green roofs and water-permeable paving to reduce surface water, and thus flooding, in future times of heavy rain. New bridges over the river are to be designed so that they will be less easily blocked during a flood.[88][89] According to the UK Government's Environment Agency, the development will provide opportunities to adapt the site to climate change, and give the community attractive recreational space and improved wildlife areas. Involved parties are Scott Wilson Group, RPS, ERM Consultants, Joseph Partners and the London Borough of Barnet.[89]

Notable floods

The earliest flood record is 1682.

- 1682: A very violent storm of rain, accompanied with thunder and lightning, caused a sudden flood, which did great damage to the town of Brentford. The whole place was overflown; boats rowed up and down the streets, and several houses and other buildings were carried away by the force of the waters.[90]: 39–58

- 1841: Brentford was flooded by the Brent Reservoir becoming overfull so that the overflow cut a breach in the earth dam. A wave of frothing and roaring water swept down the river's course taking all before it causing fatalities. Several people died.[91]

- 1976 and 1977: in the summer Britain saw drought and unusual heat with Water Companies declaring it would take six or seven years for empty reservoirs to recover. The following August, a rainy spell was followed by a day and night of torrential rain that overwhelmed the Brent reservoir — authorities decided to open the sluice gates maximally at time of highest volume and pressure, to avoid costly overflow flooding, having been under general pressure to keep stock water supplies. Later, before the river below overflowed in many sections certain local sewers overflowed, some into homes. The streets, including arterial roads were jammed and local trains blocked. Hundreds of homes and businesses closed for the clean-up, with widespread press coverage.

- 2007: August saw heavy rain cause a short bout of flash flooding in Brentford and Hanwell on roads, the Hounslow Loop Line and London Underground.

- 2009: On 30 November, the Environment Agency warned residents of a flooding along River Brent from Hendon to Brentford, after a day of notably heavy rain. Several premises were temporarily flooded in Brentford and Perivale.[92]

In literature and poetry

Poet Laureate John Betjeman in his poem "Middlesex":

Gentle Brent, I used to know you

Wandering Wembley-wards at will,

Now what change your waters show you

In the meadowlands you fill!

Recollect the elm-trees misty

And the footpaths climbing twisty

Under cedar-shaded palings,

Low laburnum-leaned-on railings

Out of Northolt on and upward to the heights of Harrow hill.— John Betjeman, Middlesex

The anthropomorphic personification of the river appears as one of the daughters of Mama Thames in the novel Rivers of London.

Imagery

River Brent at Brent Cross. The Ordnance Survey 1:50,000 scale mapping shows a sea of dark green here as the A406 North Circular Road and the A41 Hendon Way meet at the Brent Cross Flyover. A small weir impounds a head of water as the river flows down towards the Brent Reservoir.

River Brent at Brent Cross. The Ordnance Survey 1:50,000 scale mapping shows a sea of dark green here as the A406 North Circular Road and the A41 Hendon Way meet at the Brent Cross Flyover. A small weir impounds a head of water as the river flows down towards the Brent Reservoir. A surface water drain outflow into the River Brent on the right hand bank.

A surface water drain outflow into the River Brent on the right hand bank. The River Brent at Vicar's Bridge, Alperton. Here the river serves as the boundary for two London boroughs: Ealing (left bank) and Brent (right bank).

The River Brent at Vicar's Bridge, Alperton. Here the river serves as the boundary for two London boroughs: Ealing (left bank) and Brent (right bank). An assumed surface water storm drain discharging into the river.

An assumed surface water storm drain discharging into the river. The River Brent at Hanwell Bridge, Hanwell, W7 See 205141 for view from bridge on the opposite side of the road.

The River Brent at Hanwell Bridge, Hanwell, W7 See 205141 for view from bridge on the opposite side of the road. Remains of a weir on the River Brent Looking westward from the right hand bank.

Remains of a weir on the River Brent Looking westward from the right hand bank. Hanwell Bridge, Uxbridge Road as it crosses the River Brent, looking east.

Hanwell Bridge, Uxbridge Road as it crosses the River Brent, looking east. The confluence of Rivers Thames and Brent. The motorised barge is heading up the River Brent. From this point as far as Hanwell the Brent has been canalised and shares its course with the main line of the Grand Union Canal. From Hanwell the Brent can be traced to various sources in the Barnet area.

The confluence of Rivers Thames and Brent. The motorised barge is heading up the River Brent. From this point as far as Hanwell the Brent has been canalised and shares its course with the main line of the Grand Union Canal. From Hanwell the Brent can be traced to various sources in the Barnet area. River Brent near Greenford.

River Brent near Greenford.

See also

Notes and references

- Notes

- References

- 1 2 Baxter, Alan (January 2011). "11. Brent River Valley". London's Natural Signatures: The London Landscape Framework (PDF). pp. 74–77. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- 1 2 Canham, Roy; Glanville G H (1978). A London Museum Archaeological Report: 2000 years of Brentford. Ch 2; pg 3. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11-290176-1

- ↑ See Geology of Britain Viewer (British Geological Survey) for more information on the distribution of all the geological formations mentioned in this article.

- ↑ Gibbard, P.L. & Lewin, J., 2003 ("Gibbard & Lewin 2003"), The history of the major rivers of southern Britain during the Tertiary, Journal of the Geological Society, 160, pages 829-845. Tectonic map and Palaeocene sections. Online at www.qpg.geog.cam.ac.uk.

- ↑ Salter, A.E. (1905), On the superficial deposits of central and parts of southern England, Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 19, pages 1–56.

- ↑ As summarized in, for example, Bridgland, D.R. (1994, 2012), Quaternary of the Thames, Geological Conservation Review Series, Springer Science & Business Media, ISBN 978-94-010-4303-8, ISBN 978-94-011-0705-1 (eBook) (originally published by Chapman and Hall).

- ↑ Bridgland, D.R. and Gibbard, P.L. (1997), Quaternary River Diversions in the London Basin and the Eastern English Channel, Géographie physique et Quaternaire, vol. 51, n° 3, 1997, pp. 337-346. Online at www.erudit.org/fr/revues/. See Figure 1.

- ↑ Stanmore Gravel Formation, British Geological Survey Lexicon of Names Rock Units.

- ↑ Humphreys, G. (1905), Excursion to Hampstead, Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, Volume 19, Issue 5, pages 243-245 (remark by A.E. Salter, page 243). Patches of Pebble Gravel also occur on the summit of Hampstead Heath, at an altitude of about 135 metres, where they overlie Eocene Bagshot Sand. (The more extensive deposits of Pebble Gravel which are found on the Bushey Heath plateau lie directly on London Clay and Claygate Beds.)

- ↑ Wooldridge, S.W. (1927), The Pliocene Period in western Essex and the preglacial topography of the district, Essex Naturalist, 21, page 247; online at www.essexfieldclub.org.uk.

- ↑ Bridgland, D.R. (1994, 2012), Quaternary of the Thames, Chapter 3, Part1, Harrow Weald Common. Bridgland suggested that the Stanmore Gravel could have been contemporary with the Stoke Row Gravel of the proto-Thames. In Lee, J.R., Rose J. and others (2011), The Glacial History of the British Isles during the Early and Middle Pleistocene: Implications for the long-term development of the British Ice Sheet, pages 59-74 in Quaternary Glaciations - Extent and Chronology, a Closer Look, Developments in Quaternary Science, 15, (Amsterdam: Elsevier), it was suggested that the Stoke Row terrace was of Marine Isotope Stage 68 age, about 1.9 million years ago. Lee, etc also suggested that the Westland Green terrace of the proto-Thames (which Bridgland suggested was of the same age as the Northaw gravel) was of MIS 62-54 age, around 1.8-1.6 Mya.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gibbard, P.L. (1979), Middle Pleistocene drainage in the Thames Valley, Geological Magazine Volume 116, Issue 1 January 1979.

- ↑ Dollis Hill Gravel Member, British Geological Survey Lexicon of Names Rock Units.

- 1 2 Murton, Della K. and Murton, Julian B. (2012), Middle and Late Pleistocene glacial lakes of lowland Britain and the southern North Sea Basin. Quaternary International, Volume 260, 18 May 2012, Pages 115-142, Fig. 7A.

- ↑ When the Dollis Hill Gravel was laid down, the River Wey would have been flowing across the North Downs at Guildford, and the River Mole would have crossed at Dorking - as now in both cases. Gibbard (1979) suggested that the two rivers were "confluent near Weybridge and from there flowed north-eastwards to Finchley going on to join the Thames east of Ware". Today, of course, the two rivers stay apart right up to their respective junctions with the River Thames at Weybridge and Hampton Court.

- ↑ Gibbard (1979) found deposits of Dollis Hill Gravel up to six metres thick in the vicinity of the Finchley Gap. According to the British Geological Survey (Lexicon of Names Rock Units), Dollis Hill Gravel generally can be up to 15 metres thick.

- ↑ The highest Dollis Hill Gravel deposits at 100 metres have not been dated precisely. But deposits of Gerrards Cross Gravel (which were laid down by the proto-Thames) have been tentatively estimated to be nearly one million years old (see Lee, J.R., Rose J. and others (2011), where Gerrards Cross Gravel is dated at Marine Isotope Stage 22, about 0.9 Ma). Such deposits have been mapped, at a similar altitude (about 100 metres), to the north-west, near Radlett. There is no certainty that the oldest Dollis Hill Gravel was laid down at exactly the same time as the Gerrards Cross Gravel, but the ages are probably comparable, because, in any given section of the London Basin, the altitude of river-borne Pleistocene deposits is normally closely correlated with their age. (This age-altitude correlation principle is illustrated in, for example, Figure 3.2, Bridgland (1994, 2012), Chapter 3, Idealized transverse section through the classic Middle Thames sequence of the Slough-Beaconsfield area, with the oldest Thames gravels at an altitude of over 150 metres, and the youngest at almost sea level.)

- ↑ Figures in Gibbard (1979) suggest that the gradient of the proto-Mole-Wey valley floor was 30 cm/km north-east of Finchley, and 45 cm/km south-east of that location.

- ↑ Brown, Joyce C. (1959), The Sub-Glacial Surface in East Hertfordshire and Its Relation to the Valley Pattern. Transactions and Papers (Institute of British Geographers), 1959, No. 26, pp. 37-50. See in particular Figure 1, Figure 4, and page 49 - "There is seen to be a general correspondence between the present and pre-glacial drainage lines".

- ↑ Nineteenth century studies of glacial deposits in the Vale of St Albans and in the Finchley area include: Prestwich, Joseph, On the Occurrence of the Boulder Clay, or Northern Clay Drift, at Bricket Wood, Near Watford, The Geologist, June 1858, page 241; Walker, H. (1871), On the glacial drifts of North London, Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 2, page 289; and Goodchild, J.G. and Woodward H.B. (1887), Excursion to Whetstone and Finchley, Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 10, page 145.

- ↑ Sherlock, R.L. and Noble, A.H. (1912), On the glacial origin of the clay-with-flints of Buckinghamshire, and on the former course of the Thames. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, 68, pages 199–212.

- ↑ Gibbard P.L., 1977, Pleistocene History of the Vale of St Albans, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, Vol. 280, No. 975 (Oct. 17, 1977), pp. 445-483.

- ↑ 1:50,000 geological map, Sheet number 255, Beaconsfield, 2005, British Geological Survey.

- ↑ Wooldridge, S.W. (1938), The glaciation of the London Basin, and the evolution of the Lower Thames drainage system. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, 94, pages 627–664. Although Wooldridge argued that the gap at Carpenders Park in the Pebble Gravel interfluve was initiated by an ice advance, his hypothesis about the date and nature of that ice advance has since been shown to be erroneous - see Bridgland, D.R. (1994, 2012), chapter 1, The Diversion of the Thames. Wooldridge also argued that a similar gap, at Northwood a little to the west (followed today by the London to Aylesbury railway line), was initiated by an ice advance. It is possible that that gap also served as an overflow channel for the obstructed Anglian Thames.

- ↑ London topographic map.

- ↑ The geological map illustrates strikingly that outcrops of Dollis Hill Gravel to the west and south of the Finchley Gap are relatively few in number and are confined to relatively small areas, such as on the crests of isolated hills like Dollis Hill itself, whereas east and north of the Finchley Gap the remaining Dollis Hill Gravel covers notably wider areas, including the areas under expanses of remaining glacial till in North and East Finchley, and east of Cuffley. However, prior to the Anglian glaciation, the proto-Mole-Wey river must have laid down deposits of Dollis Hill Gravel which covered similar extents both west and east of the Finchley Gap. The reason for the difference in extent today is because the pre-Anglian Dollis Hill Gravel west of the Finchley Gap was subject to much more erosion during and after the Anglian Stage than the pre-Anglian Dollis Hill Gravel east of the Finchley Gap. The eastern Dollis Hill Gravel was first protected by the ice lobe which covered it. As Wooldridge (1938, pages 659-60) first recognised, that ice lobe had little if any erosive power, so not much of the Dollis Hill Gravel which it overrode would have been removed by the ice. And after that ice lobe melted and retreated, much of the eastern Dollis Hill Gravel was protected by a covering of glacial till left behind by the ice. By contrast, the western Dollis Hill Gravel was left open to erosion in various ways - by trapped water which was rising in front of the ice lobe, by proto-Thames water overflowing gaps in the watershed between the proto-Thames and proto-Mole-Wey catchments, and then by meltwater pouring from the snout of the retreating ice lobe. And a little further south, all previous Dollis Hill Gravel was removed by the surging waters of the newly-diverted Thames.

- ↑ Bridgland D.R. and Gibbard P.L, 1997, Quaternary River Diversions in the London Basin and the Eastern English Channel, Géographie physique et Quaternaire, vol. 51, n° 3, 1997, p. 337-346. See Figure 1. Online at www.erudit.org.

- ↑ These isolated hills are mostly on London Clay and have a protective cap of Dollis Hill Gravel. Their isolated forms bears witness to the fluvial erosion which was carried out on all sides of each hill,notably by the pro-glacial lake. They include Horsenden Hill, Wembley (Linden Avenue), Barn Hill, Dollis Hill and Hendon (Sunningfield Road). Another such isolated hill, at Colindale (Wakemans Hill Avenue), does not have a cap of Dollis Hill Gravel, but it probably did have one until a recent geological date, because its summit is at about the same altitude (90 metres) as the isolated hill with a Dollis Hill Gravel cap at Hendon, a short distance to the east. In all these cases, the permeable Dollis Hill Gravel has protected the easily-eroded London Clay below from being removed. It is not uncommon to find isolated London Clay hills in the London area which are capped by a protective layer of sand or gravel. Other examples include Forty Hill (capped by Boyn Hill Gravel) and Shooter's Hill (capped by Stanmore Gravel).

- ↑ 1:50,000 geological map, Sheet number 255, North London, 2006, British Geological Survey. See also BGS Geology Viewer.

- ↑ Deposits of "Black Park Gravel" (see BGS Lexicon of Names Rock Units) (which are identified on current geological maps (see BGS Geology Viewer) and which were laid down by the Thames during the latter part of the Anglian stage after it was diverted southwards, indicate the approximate route then taken by that river, between Uxbridge and Richmond. However, the Thames at that time (as during subsequent cold periods of the Pleistocene) was probably flowing as a broad, braided watercourse, in a kilometres-wide flood plain (see Ellison, R.A. 2004, Geology of London, British Geological Survey, pages 54 and 59. Online at pubs.bgs.ac.uk).

- ↑ This is the deposit of "Black Park Gravel" at Hanger Lane. See Gibbard, P.L. (1985), The Pleistocene history of the Middle Thames Valley, Cambridge University Press, pages 23-24. This gravel contains a wide variety of material which could only have been transported to the area by the ice sheet which reached Finchley, including granite, quartzite, Carboniferous Limestone and red sandstone. See Bromehead, C.E.N. and Dines, H.G. (1925), The geology of North London. Explanation of one-inch geological sheet 256 new series, British Geological Survey, pages 39-40; online at pubs.bgs.ac.uk.

- ↑ A similar process of drainage reversal during the Anglian stage led to the creation of the south-flowing lower section of the River Lea, which was able to establish a link to the diverted Thames to the east of Hampstead Heath. Similarly, in the former valley of the proto-Thames, the direction of drainage was reversed between the Vale of St Albans and Uxbridge, thus initiating today's River Colne. See Bridgland (1994, 2012), Chapter 3,Moor Mill Quarry. Rivers flowing down the Chiltern dip slope from the north-west such as the Gade and Chess, which were previously left-bank tributaries of the north-east-flowing Thames, became right-bank tributaries of the south-flowing Colne.

- ↑ The description given above of how the drainage reversal in what is now the River Brent catchment area was brought about, and how isolated hills such as Horsenden Hill were formed, is a simplification of what must have happened. The readjustment of the drainage pattern in the areas referred to, and the remodelling of the area's topography during the Anglian stage, would have been a complex, and maybe at times chaotic, process, and it would have taken place over at least many hundreds, and probably many thousands, of years.

- ↑ Bridgland, D.R. (1994, 2012), chapter 1, "Terrace Formation".

- ↑ 60 metres is the approximate altitude of Thames Black Park deposits at Northolt Park and Richmond.

- ↑ Wooldridge, S.W. and Linton, D.L. (1955), Structure, surface and drainage in South-East England (first published in 1939), Philip, London (text online at archive.org): "At Finchley ... the surface of the boulder-clay" (where it lies on Dollis Hill Gravel) "varies in height from 250-300 feet and the sub-drift surface is at 224 feet at Church End." 224ft = c. 68 metres.

- ↑ Boyn Hill Gravel Member, British Geological Survey Lexicon of Names Rock Units.

- ↑ Taplow Gravel Member, British Geological Survey Lexicon of Names Rock Units.

- ↑ Kempton Park Gravel Membe, British Geological Survey Lexicon of Names Rock Units.

- ↑ Ellison, R.A. 2004, Geology of London, page 70.

- ↑ The description on this page of the history of the formation of isolated, mostly gravel-capped hills such as Horsenden Hill, is, like the description offered for the major drainage reversal, a simplification of what must have happened. But a similar combination of factors, involving pro-glacial lakes, meltwater flows, and subsequent evolution under a primarily periglacial regime, also led to the formation of a number of relatively small, isolated, gravel-topped hills adjacent to the eastern Fenland margin in East Anglia, in the Mildenhall - Lakenheath area (albeit in a different time frame and in a different geological setting). See Gibbard P.L., West R.G., Hughes P.D., 2018,Pleistocene glaciation of Fenland, England, and its implications for evolution of the region, R. Soc. open sci. 5:170736. and Gibbard, P. L. and others, 2009, Late Middle Pleistocene glaciation in East Anglia, England, Boreas, Vol. 38, pp. 504–528.

- ↑ Gibbard, P.L., Wintle, A.C. and Catt, J.A., 1987, Age and origin of clayey silt 'brickearth' in west London, England, Journal of Quaternary Science, Vol. 2, pp. 3-9. Downloadable from www.researchgate.net.

- ↑ Langley Silt Member, British Geological Survey Lexicon of Names Rock Units.

- ↑ "The Physique of Middlesex". www.british-history.ac.uk. 1969. pp. 1–10. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- 1 2 3 Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Archived 27 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Neaves, Cyrill (1971). A history of Greater Ealing. United Kingdom: S. R. Publishers. pp. 103, 105, 128, 208. ISBN 978-0-85409-679-4.

- ↑ The hundred of Gore, A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 4 (1971), pp. 149-50. Date accessed: 18 August 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Barnet First, Barnet London Borough, Sept/Oct 2007, page 5 (Internet Archive document).

- ↑ "The Decoy Brook". "Middlesex County Council" (Nick Papadimitriou).

- ↑ "Sources of the Silkstream". Middlesex County Council (Nick Papadimitriou).

- ↑ "London Borough of Brent Strategic Flood Risk Assessment (SFRA) Level 1" (PDF). www.brent.gov.uk. London Borough of Brent. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Brent River Park (Brent Council)". Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ↑ River Brent from Lilburne walk at Tokyngton Recreation Ground:: OS grid TQ2084 :: Geograph Britain and Ireland - photograph every grid square!

- 1 2 3 4 5 "river brent, perivale, greenford, middlesex". perivale.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ "BRENT RIVER CORRIDOR Improvement Plan" (PDF). Thames 21. Brent Catchment Partnership. 2014. pp. 5, 6. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- 1 2 3 Darryl (23 July 2009). "river brent | 853". 853blog.wordpress.com. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ "Grand Union Canal Walk - Brentford to West Drayton". Luphen.org.uk. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ "Canal & River Trust". Waterscape.com. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ "Home - Transport for London". Tfl.gov.uk. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ "Brentford Dock History". Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "Brentford Dock's 150th Anniversary". Archived from the original on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- 1 2 Birds of Brent Reservoir, 2001 ISBN 978-0-9541862-0-3

- ↑ "Lower Dollis Brook". Greenspace Information for Greater London. 2006. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012.

- ↑ "iGiGL – helping you find London's parks and wildlife sites". Greenspace Information for Greater London. 2006. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012.

- ↑ Hewlett, Janet (1997). Nature Conservation in Barnet. London Ecology Unit. pp. 79–80. ISBN 1-871045-27-4.

- 1 2 "Brent Council". Brent.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Ealing - News, views, gossip, pictures, video - Get West London". Ealinggazette.co.uk. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- 1 2 "Brent River Park - Walks". The AA. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ Stern, Harold (6 November 2006). "River Brent - in spite of the pollution around, a heron pays a visit | Flickr - Photo Sharing!". Flickr. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The River Restoration Centre - Case Studies - River Brent, Tokyngton Park". Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The River Restoration Centre - River Brent Projects Map". www.therrc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "Brent River Park Phase II" (PDF). Therrc.co.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Archived 6 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Ealing Cycling Campaign Routes and Rides". Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ↑ "EALING_factsheet" (PDF). www.grdp.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- 1 2 "Powered by Google Docs". docs.google.com. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ↑ "BRENT_factsheet" (PDF). www.grdp.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ↑ "Silk Stream Sewage Pollution". YouTube. 28 March 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ "Ealing - News, views, gossip, pictures, video - Get West London". Ealinggazette.co.uk. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ "The Brent News and Sport | Get all the News and Sport in Brent". Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ↑ "Waterway Champions | River Brent Clean-up, Hanwell". Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- 1 2 "Brent River Park Phase 1 - Community Projects" (PDF). Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ "Plain English guidance on environmental regulations for your business". Netregs. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ "The River Restoration Centre - River Brent Projects Map". Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ↑ "Stonebridge Estate" (PDF). Therrc.co.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ "Plans to clean up River Brent if £4.5bn scheme is passed (From Times Series)". Times-series.co.uk. 5 November 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- 1 2 "Environment Agency - Integrated planning: Brent Cross Cricklewood regeneration, London". Archived from the original on 17 December 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ↑ Brentford | British History Online. 1795. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

- ↑ "Floods and reservoir safety integration Vol 2: Appendix D" (PDF). Defra. p. 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- ↑ "Flood warning for River Brent (From Richmond and Twickenham Times)". Richmondandtwickenhamtimes.co.uk. 30 November 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

External links

- River levels from Hendon to Brentford

- The Waterways of Brent . Accessed 2007-08-18

51°28′55″N 0°18′14″W / 51.482°N 0.304°W