| Part of the series on |

| Russian martial arts |

|---|

|

| Types |

Russian boxing (Russian: Кулачный бой, romanized: Kulachniy Boy, lit. 'fist fighting, pugilism') is the traditional bare-knuckle boxing of Rus' and then Russia. Boxers will often train by punching buckets of sand to strengthen bones, and prepare minutes before the fights.

History

The earliest accounts concerning the sport date to the 13th century.[1] Supposedly, fist fighting was practiced even prior to the Christianization of Kievan Rus', at celebrations dedicated to Perun.[2]

Metropolite Kiril, in 1274, created another one of many personally-instituted rules, declaring expulsion from Christianity for any of those who fist-fight and do not sing a prayer or hymn at the burial of someone who died during a fist fight.[3] The government itself never supported, but also never opposed fist fighting.[3]

Russian boyars used the sport as mass entertainment, and acquired the best fighters for competitions.[4]

The fights most often took place in holiday times and in crowded places. In winter it took place on ice. First the young children fought, then every pair was more grown up than the previous, ending with the last and most notable fist fighters.[5][6]

In two orders released in 1684 and 1686 fist fighting was forbidden, but the sport continued to live.[7][8]

All regions had their heroes at the sport, but the region with the most famous ones historically is Tula.[9][10]

There are documents saying Peter the Great liked to organize fist fights "in order to show the ability of the Russian people".[11]

In 1751, a mass fist fight took place on a street in Saint Petersburg, which came to the attention of Empress Elizabeth of Russia. After that the Empress forbade the organization of fist fights on the territory of Moscow and Saint Petersburg.[3]

During the reign of Catherine the Great, the popularity of fist fighting was growing again,[11] and it is said that Count Orlov was a good fist fighter himself and even invited notable fist fighters to compare powers.[11]

In 1832, Nicholas I of Russia completely forbade fist fights as "harmful fun".[3]

Legacy

K.V. Gradopolov, then the most important Soviet specialist in Boxing, authored a 1941 work about using proper technique when fist-fighting. In that book, he offered a new exercise, called "group boxing", and he mentioned it was an ancient Russian sport (what he was talking about, was the "Stenka na Stenku" version).[12]

Rules and types

Every region in Russia incorporated different rules unlike the sport of boxing. In some places they fought with bare arms, while in other they stretched the sleeves over the fists. There were cases where participants would cheat by putting iron under their sleeves.[13]

There are three types of Russian fist fighting: the first is the singles type, a one-on-one fight; the second type is a team fight also known as "wall on wall". The third one, "catch drop", was the least practiced.[14][15] There were several versions of the singles fight. One version was like modern boxing, where one fighter hits the other wherever he wants or can. The other version is when the fighters take turns hitting each other. Escaping from a punch, answering it not on turn, and moving aside were not allowed; all that could be done was to use the hands to try to protect one's own body.[16] Victory could come in few cases: when one of the fighters falls, till first blood, or till one of the fighters gives up.[17]

The "wall-on-wall" fight (with anywhere from dozen to several hundreds participants) was performed strictly by rules and could go on for hours. Both "walls" had a chief fighter, who served as a tactician and a commanding officer. "Walls" themselves were tight straight formations 3-4 ranks deep. Repeated attacks were performed, aiming to push the opposing "wall" out of the game area. Basic tactics were used, such as breaching using heavy fighters (who were usually held in reserve), encircling, false retreat and others; but as a rule, tight wall formation never broke. Tactics also included battle planning. The "wall-on-wall" fights, while performed for entertainment, were in fact close to military training. For example, notable ethnographer V. Gilyarovsky recalled that during his voluntary service in an infantry regiment soldiers often staged wall-on-wall fistfights with factory workers.[18]

A famous phrase in Russian, "Do not hit a man when he's down", has roots in that sport.[19]

Fist fighting in Russian popular culture

As for centuries fist fighting was so popular and was such a part of Russian folk life,[20] it occurred frequently in Russian literature and art.

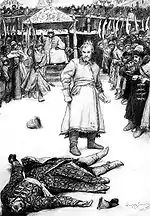

The most famous portrayal of a Russian fistfight is in Mikhail Lermontov's poem, The Song of the Merchant Kalashnikov. There, the fistfight tales place as a form of honor duel between an oprichnik (government police agent) and a merchant. It is notable that, according to Lermontov, both characters use combat gloves ('rukavitsy' — reinforced mittens). Though it may be an example of poetic license, the poem states that the first connected blow by Kalashnikov bent a large bronze cross hanging from his opponent's neck, and the second fractured the opponent's temple, killing him. The fight also features in the opera The Merchant Kalashnikov by Anton Rubinstein (1880).

In the 19th century Sergei Aksakov watched famous fist fights in the Kaban frozen lake in Kazan, and later wrote about them in his "Story about student life". Some decades later, at the same lake, the young future opera-singer Feodor Chaliapin took part in a similar fight: "From one side came we, the Russians of Kazan, from the other side the Tatars. We fought hard without feeling sorry for ourselves, but never broke the historic rules of not to hit one that is already down, not to kick, and not to keep iron up one's sleeves".[21] Later the young Chaliapin was attacked in a fight over a girl, but thanks to his proficiency in fist fighting, he won. He wrote: "He jumped to beat me, and even though I was afraid of the police, learning fist fighting at the frozen lakes of Kazan helped me, and he humiliatingly lost".[22]

The Russian poet Sergei Yesenin in his autobiography notes "About myself" told that his grandfather taught him fist fighting.[23]

One of the heroes in the book "Thief" by the Soviet novelist Leonid Leonov said: "In childhood, it happened, only in fist fights I found real friends... And was never wrong! Because only in a fight the whole human nature comes out".[24]

Claims have been made that the Russian nobility favoured fistfights over duels, but on the other hand it has been suggested that the nobility actually were against fistfights and preferred weapons.[25]

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ Russian Fist Fighting. "Летописцы наши говорят об ней, еще в начале XIII в. [Our sources talked about it already at the 13th century.]"

- ↑ Sevostyanov, V. М.; Burtsev, G. А.; Pshenitsyn, А. V. (1991). Рукопашный бой [Russian Pugilism]. Moscow: Data Strom. p. 190. ISBN 978-5-7130-0003-5.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Russian Civilization". К истории кулачных боёв. Archived from the original on May 19, 2007. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ↑ Sakharov, Ivan P., Сказания русского народа, p. 129. "Было время, когда русские бояре, собравшись повеселиться, свозили из разных городов бойцов для потешения. [There was a time when Russian boyars when came together to have fun, brought from different cities fighters for fun.]"

- ↑ "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-08-22. "лишь постепенно вводились в дело все более сильные отряды. Первыми выходили ребятишки, затем подростки, юноши, неженатые парни, а уж затем - взрослые мужчины. [Only after a while the strongest ones were brought. The first were the kids, then teens, then lads, and only then grown up men.] "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ Labzyuk, Sergei, "Историческая справка: кулачный бой". "Бои происходили обыкновенно в праздничные дни и при жилых местах, а зимой чаще всего на льду. Сначала пускали вперед как бы застрельщиков, мальчишек. За ними мало-по-малу группировались более взрослые, но главная партия противников оставалась в резерве, особенно известные по своей силе и искусству бойцы. [The fights usually took place at holidays and in rural areas, and in winter most often on ice. First the boys were let in, and then more and more grown ups. The best fighters were kept for the end.]"

- ↑ Bain, Robert Nisbet (1897). The Pupils of Peter the Great: A History of the Russian Court and Empire from 1697 to 1740. Westminster: A. Constable and Co. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-548-05007-1.

...Thus a Ukaz was issued to put a stop to the brutality of the Kulachny boi, or fist-fight. This popular game was not abolished, but those who chose to amuse themselves thereby, were to do so, in future, under police supervision ...

- ↑ Russian Fist Fighting. "Указами 1684 года ноября 2, 1686 года марта 19 и другими, строго воспрещались кулачные бои... Было время, что старики, воспламеняя умы молодых людей, несбыточными рассказами об удальстве бойцов, пробуждали в них страсть к кулачному бою." (With orders released in 1684, and 1686, Fist fights were forbidden... The old people, with their stories about the sport encouraged the young people to continue with it)

- ↑ Russian Fist Fighting. "Тульские бойцы и ныне славятся, но каждое место имело своих удальцов." (Tulas fighters were always glorious, but every place had its heroes)

- ↑ Sakharov, Ivan P., Сказания русского народа, p. 129. "Лучшими бойцами один на один считались тульские [The best fighters in one-on-one were considered Tula's fighters.]"

- 1 2 3 Romanenko, M. I. Интернет-портал "Легендарный Физтех", "Физтех-центр". Краткий исторический обзор развития бокса как вида спорта [A brief historical overview of the development of boxing as a sport] (in Russian). Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ↑ "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-08-22. "1941 году ведущий советский специалист по боксу К. В. Градополов рассказывал в своей книге о методах обучения воинов кулачному прикладному искусству. Предлагалось там такое необычное упражнение, как «групповой бокс». Автор прямо указывал, что «прообразом группового бокса (организованного и ограниченного определенными правилами) является русский самобытный народный спорт «стенка на стенку». (In 1941 the leading Soviet specialist in boxing K.V. Gradopolov told in his box about methods to teach soldiers how to fight with fists. He there offered a new exercise, 'group boxing'. He said there that the prototype of the 'group boxing' was the Russian folk sport "Wall on Wall"] "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ Sakharov, Ivan P., Сказания русского народа, p. 129. "Часто случалось, что хитрые и слабые бойцы закладывали в рукавицы бабки-чугунки для поражения противников. [Often it occurred, that weak fighters inserted iron into their sleeves]"

- ↑ Sakharov, Ivan P., Сказания русского народа, p. 129. "Кулачные бои совершались разными видами. Более всех почитался: бой один на один, за ним—стена на стену, а менее всех сцеплялка-свалка. [There were different types of fist fighting. The most famous was a one-on-one, after that the wall on wall, and the least famous was the catch-drop."]

- ↑ "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-08-22. "Кулачный бой практиковался у нас в трех формах: один на один («сам на сам»), стенка на стенку и «сцеплялка–свалка». [Fist fighting was practiced in three ways. One-on-one, wall on wall, and catch-drop."] "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ Labzyuk, Sergei, "Историческая справка: кулачный бой". "Также существовал кулачный бой 'удар на удар' или 'раз за раз', когда противники наносили удары по очереди. Уклоняться от удара, отвечать на него, переступать ногами запрещалось, можно было лишь прикрыть руками наиболее уязвимые места. [There was also a fist fighting type 'hit on hit' or 'one for one', when the opponents gave punches on turn. Evading a punch, answering it not on turn, moving one's legs was not allowed. All could be done was to use the hands to try to protect the more painful areas]"

- ↑ Labzyuk, Sergei, "Историческая справка: кулачный бой". "Бились по различным правилам: - до сбивания на землю ударом (до трех сбиваний) - до первой крови - до сдачи противника и признания своего поражения. Также существовал кулачный бой 'удар на удар' или 'раз за раз', когда противники наносили удары по очереди. Уклоняться от удара, отвечать на него, переступать ногами запрещалось, можно было лишь прикрыть руками наиболее уязвимые места. [There were different types of rules. 1. Till one falls. 2. Till first blood. 3. Till one gives up.]"

- ↑ Кулачный бой на Руси Спортивная жизнь magazine, No. 7 1998 Archived January 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-08-22. "Одно из правил кулачного боя стало даже пословицей, символизирующей русское благородство в бою: «Лежачего не бьют». [One of the rules of fist fighting even turned into a well-known phrase, which showed the Russian nobility: "Do not hit a man when he's down."] "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-08-22. "Широчайшей географией кулачных боев, их повсеместным распространением объяснялось то, что кроме русских в них со временем стали принимать участие и представители иных национальностей, обитавших в России: древняя чудь, татары, мордовцы. И многие другие." (The wide territory the fist fight was practiced on brought the sport to other nations like the Tatars, Mordvins, and many others) "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on August 22, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-08-22. "Еще в 1806 году С. Т. Аксаков наблюдал знаменитые кулачные бои в Казани, на льду озера Кабан, и впоследствии описал их в своем «Рассказе о студенческой жизни». А через восемь десятилетий в тех же боях азартно дрался великий русский артист Ф. И. Шаляпин. Уже увенчанный мировой славой, он делился дорогими его сердцу воспоминаниями: «Сходились с одной стороны мы, казанская Русь, с другой - добродушные татары. Дрались отчаянно, не щадя ни себя, ни противников. Но и в горячке яростной битвы никогда не нарушали установленных искони правил: лежачего не бить, присевшего на корточки - тоже, ногами не драться, тяжести в рукавицы не прятать»." "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-08-22. "Однажды, когда Федор уже начал взрослеть, навыки кулачного боя выручили его в критической ситуации. Его несчастный соперник в любви - городовой - попытался было поколотить начинающего хориста, но тот вовсе не забыл, как хаживал в стенке на озере Кабан, и крепко проучил блюстителя порядка. «Он бросился бить меня. Но хотя я очень боялся полиции, однако опыт казанских кулачных боев послужил мне на пользу, и городовой был посрамлен»." "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-08-22. "«Дедушка иногда сам поддразнивал на кулачку и часто говорил бабке: «Ты у меня, дура, его не трожь, он так крепче будет!». Так написал сам поэт в автобиографических заметках «О себе»." (Sometimes my grandfather teased me to fist fight and told my grandmother: "You, my stupid, don't touch him. That way he'll be tougher". That's what the poet himself wrote in the autobiographic notes "About Myself") "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-08-22. "Один из героев его романа «Вор» говорит: «В мальчишестве, бывало, только на кулашнике и подберешь себе приятеля... И ведь ни разу не ошибался! Это оттого, что именно в бою «вся людская повадка насквозь видна»." (One of the heroes in the book "Thief" by the Soviet novelist Leonid Leonov said: "In childhood, it happened, only in fist fights I found real friends... And was never wrong! Because only in a fight the whole human nature comes out") "Кулачный бой". Archived from the original on August 22, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ Beltrame, Franca (2001). "On the Russian Duel: Problems of Interpretation". The Slavic and East European Journal. 45 (4): 741–746. doi:10.2307/3086132. JSTOR 3086132.

There was a claim brought up that the Russian nobility preferred fistfights over duels, which is a lie because they have seen fist fighting as disgraceful

- Works cited

- Labzyuk, Sergei. Историческая справка: кулачный бой [Historical note: Fist fighting] (in Russian). Federation of Kyiv Slavonic Fist Fighters. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- "Русский кулачный бой" [Russian Fist Fighting]. Боевые искусства (in Russian). Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- Sakharov, Ivan Petrovich (1885). "Сказания о русских народных играх: Кулачный бой [Tales of Russian folk games: pugilism]". Сказания русского народа [Russian Folk Tales] (in Russian). A. S. Suborin. p. 129.

External links

- Fist fighting in USSR (Rare video)

- About the sport from the Russian ethnic games collection (Russian)

- Fist fighting in ancient Rus (Russian)

- A fist fighting fan-club (Russian)

- Kievan federation of fist fighting (Ukrainian)(Russian)

- A downloadable book about Russian fist fighting (Russian)

- An article about the Russian fist fighting (Russian)