Teenage pregnancy in the United States refers to females under the age of 20 who become pregnant. 89% of these births take place out-of-wedlock.[1] Since the 1990s, teen pregnancy rates have declined almost continuously in the United States, but the United States still has one of the highest teenage birth rates among the industrialized nations. The 5 states with the highest teen birth rate are Arkansas, Mississippi, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Alabama. According to the Centers for Disease Control, evidence suggests that the decline in teenage pregnancy is due to abstinence teaching and the use of birth control. Although the decline is considered good news, the racial/ethnic and geographic disparities continue in The United States.[2] In 2019, the birth rates for Hispanic teens and non-Hispanic Black teens were more than double than the rates for white teens.[3]

In 2022 research organization Child Trends found that teen birth rates in the United States had vastly declined in the previous 30 years. In 2021, it has been estimated that the percentage of 15-year-old females to have a birth before the age of 20 is 6 percent, which is a 76 percent decline in 30 years.[4][5]

Pregnancies

According to the Centers for Disease Control, more than four out of five, or 80%, of teenage pregnancies are unintended.[6] In 2010, of the majority of pregnancies to adolescent females in the United States, an estimated 60% ended in live birth, 15% ended in miscarriage, and 30% in abortion.[7] In 2012, there were 104,700 maternal hospital stays for pregnant teens; the number of hospital stays for teen pregnancies decreased by 47 percent from 2000-2012.[8]

In 2014, 249,078 babies were born to girls aged 15–19 years old. This is a birth rate of 24.2 per 1000 girls.[9] However, most adolescents who give birth are over the age of 18. In 2014, 73% of teen births occurred in 18–19 year olds. Pregnancies are much less common among girls younger than 15. In 2008, 6.6 pregnancies occurred per 1,000 teens aged 13–14. In other words, fewer than 1% of teens younger than 15 became pregnant in 2008.[10] Pregnant teenagers tend to gain less weight than older mothers, due to the fact that they are still growing and competing for nutrients with the baby during the pregnancy.[11]

Teen pregnancy is defined as pregnancies in girls under the age of 20, regardless of marital status. Teen pregnancy rates have dropped 9% since 2013.[9] Between 1991 and 2014, teenage birth rates dropped 61% nationwide.[12]

Teenage birth rates, as opposed to pregnancies, peaked in 1991, when there were 61.8 births per 1,000 teens, and the rate dropped in 17 of the 19 years that followed.[13] Three in ten American girls will get pregnant before age 20. That is almost 750,000 pregnancies a year.[14] Nearly 89% of teenage births occur outside of marriage.[7] Of all girls, 16% will be teen mothers.[15] The largest increases in unintended pregnancies were found among girls who were cohabiting, had lower education, and low income.[6]

Increased pregnancy risk factors in teenagers

There are certain factors in an adolescent/teenagers life that make them more pre-disposed to getting pregnant young. Some of which include race, (see below) but also factors such as sexuality, homelessness, foster care, living in rural areas, exposure to drugs and violence can effect whether a teenager gets pregnant young.

The more risks compiled suggests that an adolescent that exhibits any of the risk listed, is at a higher risk for the other factors. This can include the use of alcohol or drugs.[16] This is consistent with the Jessor Problem Behavior Theory.[17]

By ethnicity

Black, Latina, and Native American youth experience the highest rates of teenage pregnancy and childbirth.[9] Studies show that Asians (23 per 1,000) and whites (43 per 1,000)[10][15] have lower rates of pregnancy before the age of 20. The pregnancy rate among black teens decreased 48% between 1990 and 2008, more than the overall U.S. teen pregnancy rate declined during the same period (42%).[10]

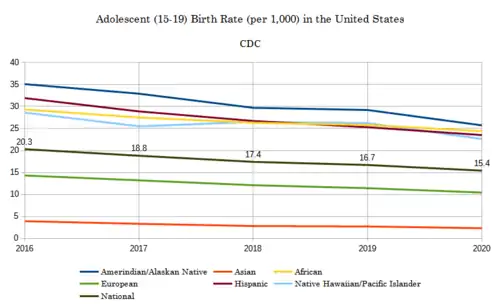

Teen birth rates decline by racial groups [2]

Teen birth rates declined from 2018 to 2019 for several racial groups and for Hispanics.1,2 Among 15- to 19-year-olds, teen birth rates decreased:

- 5.2% for Hispanic females.

- 5.8% for non-Hispanic White females.

- 1.9% for non-Hispanic Black females.

Rates for non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Natives (AI/AN), non-Hispanic Asians, and non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian, and other Pacific Islander teenagers were unchanged.

In 2019, the birth rates for Hispanic teens (25.3) and non-Hispanic Black teens (25.8) were more than two times higher than the rate for non-Hispanic White teens (11.4). The birth rate of American Indian/Alaska Native teens (29.2) was highest among all race/ethnicities.

By region

In 2013, the lowest birth rates were reported in the Northeast, while the highest rates were located in the Southeast.[7]

Birth and abortion rates of girls ages 15–19, 2010 [18]

| US State | Pregnancy rate (per 1000) | Birthrate | Abortion rate | % Abortion rate excluding stillborns and miscarriages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 62 | 32 | 9 | 17 |

| Alaska | 64 | 27.8 | 17 | 30 |

| Arizona | 60 | 29.9 | 9 | 18 |

| Arkansas | 73 | 39.5 | 9 | 14 |

| California | 59 | 21.1 | 19 | 38 |

| Colorado | 50 | 20.3 | 10 | 20 |

| Connecticut | 44 | 11.5 | 20 | 52 |

| Delaware | 15 | 20.7 | 28 | 47 |

| Washington, D.C. | 90 | 28.4 | 32 | 41 |

| Florida | 60 | 22.5 | 19 | 38 |

| Georgia | 64 | 28.4 | 13 | 24 |

| Hawaii | 65 | 23.1 | 23 | 42 |

| Idaho | 47 | 23.2 | 7 | 17 |

| Illinois | 57 | 22.8 | 15 | 32 |

| Indiana | 53 | 28 | 7 | 16 |

| Iowa | 44 | 19.8 | 9 | 23 |

| Kansas | 53 | 27.6 | 5 | 12 |

| Kentucky | 62 | 35.3 | 6 | 12 |

| Louisiana | 69 | 35.8 | 10 | 18 |

| Maine | 37 | 16.5 | 10 | 31 |

| Maryland | 57 | 17.8 | 22 | 45 |

| Massachusetts | 37 | 10.6 | 14 | 46 |

| Michigan | 52 | 21.1 | 14 | 32 |

| Minnesota | 36 | 15.5 | 8 | 25 |

| Mississippi | 76 | 38 | 9 | 14 |

| Missouri | 54 | 27.2 | 9 | 19 |

| Montana | 53 | 26.4 | 10 | 21 |

| Nebraska | 43 | 22.2 | 5 | 14 |

| Nevada | 68 | 28.5 | 20 | 34 |

| New Hampshire | 28 | 11 | 8 | 35 |

| New Jersey | 51 | 13.1 | 24 | 55 |

| New Mexico | 80 | 37.8 | 15 | 22 |

| New York | 63 | 16.1 | 32 | 58 |

| North Carolina | 59 | 25.9 | 12 | 24 |

| North Dakota | 42 | 23.9 | 6 | 18 |

| Ohio | 54 | 25.1 | 12 | 25 |

| Oklahoma | 69 | 38.5 | 8 | 13 |

| Oregon | 47 | 19.3 | 12 | 29 |

| Pennsylvania | 49 | 13.8 | 15 | 35 |

| Rhode Island | 44 | 15.8 | 16 | 41 |

| South Carolina | 65 | 28.5 | 13 | 23 |

| South Dakota | 47 | 26.2 | 4 | 11 |

| Tennessee | 62 | 33 | 9 | 18 |

| Texas | 73 | 37.8 | 9 | 15 |

| Utah | 38 | 19.4 | 4 | 13 |

| Vermont | 32 | 14.2 | 9 | 34 |

| Virginia | 48 | 18.4 | 14 | 33 |

| Washington | 49 | 19.1 | 16 | 37 |

| West Virginia | 64 | 36.6 | 9 | 17 |

| Wisconsin | 39 | 18 | 7 | 21 |

| Wyoming | 56 | 30.1 | 8 | 17 |

Parenting as a teenager

In 2017, there were 14 pregnancies per 1,000 women ages 15-17, this is the lowest record it has reached and continues to decline.[10] Births to teen mothers peaked in 1991 at 62 births per 1,000 girls. This rate was halved by 2011 when there were 31 births per 1,000 girls.[10] About 25% of teenage mothers have a second child within 24 months of the first birth.[19]

Teenagers are becoming better contracepters because they realize that their sexual partners may not be a reliable coparent. Marriage rates over the 1990s through the 2010s with teenagers has drastically declined because of this realization. Since contraception has become more obtainable for teenagers, they are preventing unwanted pregnancies.[20]

For every 1,000 black boys in the United States, 29 of them are fathers, compared to 14 per 1,000 white boys.[10] The rate of teen fatherhood declined 36% between 1991 and 2010, from 25 to 16 per 1,000 males aged 15–19. This decline was more substantial among blacks than among whites (50% vs. 26%) and about half of the rate among teen girls.[10] Nearly 80% of teenage fathers do not marry the teenage mother of their child.[21] Teenage fathers have 10-15% lower annual earnings than teenagers who do not father children.[21]

Most female teens report that they would be very upset (58%) or a little upset (29%) if they got pregnant, while the remaining 13% report that they would be a little or very pleased.[10] Most male teens report that they would be very upset (47%) or a little upset (34%) if they got someone pregnant, while the remaining 18% report that they would be a little or very pleased.[10]

Parenting as a teenager has detrimental effects on the children. Children born to teenage mothers are more likely to: be born prematurely, 50% more likely to repeat a grade, live in poverty, and suffer higher rates of abuse.[19] The sons of teen mothers are 13% more likely to end up incarcerated, and the daughters of teenage mothers are 22% more likely to become teenage mothers.[19] More than 25% of teen mothers live in poverty during their 20s.[21]

Teenage pregnancy imposes lasting hardships on two generations: mother and child. Evidence from U.S. studies show that girls who bear their first child at an early age bear more children rapidly and have more unwanted and out-of-wedlock births. Children of teenage parents are more likely to have lower academic achievements and tend to repeat the cycle of early marriage and early childbearing of their parents.[22]

Since the Great Recession, young people take three times longer to gain financial independence than it took for young people three decades ago. It is much harder for teenage parents to be able to support a family compared to the past due to the competitive work environment.[20]

Supporting teenage parents

More than 50% of teenage mothers do not graduate from high school.[14] Some high schools in the United States offer a program for pregnant and parenting teens to continue their education. These are sometimes referred to as "Teen Parent Programs".[23]

There are several benefits to these school based programs, the number one benefit being teens are able to continue their high school education. Studies have shown that when teen parents stay in school after being pregnant, they have a better chance of graduating high school.[24] Less than 2% of teen moms earn a college degree by age 30.[14] Many of these programs offer on-campus childcare. Some even require the pregnant and parenting teens to attend parenting classes or practicum classes. The parenting classes offer a place for these young parents to learn about the basic needs of a child. While, the practicum classes offer a hands on experience caring for the children in the childcare center.

Statistics show that less than 10% of teen parents earn their high school diploma by their eighteenth birthday.[25] These programs are trying to change those statistics. Currently (2016), San Diego County has seven high schools that offer these teen parent programs.

Prevention

The United States has the highest rates of teenage pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases in developed countries.[26] The two primary reasons given by teenagers for not using protection is that the chance of becoming pregnant is small, and the failure to anticipate intercourse.[27]

The best method of reducing the consequences of teenage parenthood is by providing reproductive health services to prevent teenagers from becoming pregnant in the first place.[20] Prevention can not only be beneficial on a micro level but it is also beneficial on a more macro scale. Nationally, teen pregnancies cost tax payers an average of $9.4 billion each year.[9] These costs are associated with health care, foster care, criminal justice, public assistance and lost tax revenue.[19] Teen pregnancies can be prevented by increasing access and education on the proper use of contraceptives,[6] as well as parental involvement. The best method of prevention is to integrate sex and STD education into the middle and high school science curriculum as well as addressing the effects of teenage pregnancies in the social studies curriculum.

According to studies conducted by the American Journal of Public Health, the pregnancy rate in The United States can be predictable by analyzing two indexes, the contraceptive risk index and the overall pregnancy risk index.[28] Using these indexes with previous adolescent pregnancy data, 77% of the decline in pregnancy risk was attributed to contraceptive use. The conclusion from this studies and others, is that improved contraceptive use and teachings is responsible for the decline.

International comparison

There are large differences in adolescent pregnancy rates among developed nations like Canada, France, Great Britain, Sweden and the United States. The United States has the highest number of teen pregnancies and the highest number of sexually transmitted infections compared to the other four countries. In France and Sweden during the late '90s, pregnancies were 20 per 1,000 girls at ages 15–19.[30]

In Canada and Great Britain the levels were twice that, and the United States the level was 4 times as high with 84 per 1,000 teenage girls pregnant. The likelihood of pregnant teenage girls having abortions across the four countries differ and exclude miscarriages. In the U.S. abortion rates for 15–19 years are 35% while it was 69% in Sweden, 39% in Great Britain, 46% in Canada, and 51% in France.[30]

It has been suggested that the U.S. teen pregnancy rate is higher because of the prevalence of abstinence-only sex education. As a result, many adolescents are ignorant about contraception and effective pregnancy prevention. The mentality of some education systems in the U.S. have the idea that if they do not teach safe sex, adolescents will refrain from sex. As the data concludes from above that compared to the other developed countries the U.S. is four times as likely to have a teen pregnancy. Yet the U.S. also uses less contraceptive, has more abortions and more prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases than the other developed countries.

Quality of sex education varies across the U.S, with some states offering more comprehensive education than others. 39 states require "some" education related to sexuality. 25 states are required by law to teach sex and HIV education. 17 states only require the teaching of STIs. 20 states require provision of information on contraception, 39 states are required to provide information on abstinence.11 states have no requirement.[31]

Modern decline

Although there is a noticeable decline in U.S. teen pregnancy, the current rate is three to four times more than in Canada, France, Great Britain, and Sweden. The biggest difference in the rate of pregnancies in the United States compared to other countries is that there is a very high unintended pregnancy rate in America. This unintended pregnancy rate is higher than the total teenage pregnancy rate in all of the four countries.[32]

In 2010 there was a rate of 57 pregnancies per 1,000 girls aged 15–19. Most of those girls reported that it was an unplanned pregnancy. This shows a 15% drop in pregnancies from 2008 to 2010. There is a huge decline in adolescent pregnancy for the nation as a whole. The cause of these declines are from abstaining from sex or better use of contraceptives.[33] Birth rates among younger teens ages 15–17 have also fallen faster – dropping by 50%, compared with a 39% decline among older teens ages 18 and 19.[34] Researchers have concluded that these declines stem from improvement in use of contraceptives.[33]

In 2022 research institute Child Trends found that teen birth in the United States had vastly reduced in the previous 30 years.[4][5]

Intentional teen pregnancy

According to the Journal of Pediatric Health Care, approximately 15% of all adolescent pregnancies are planned.[35] Based upon interviews conducted with pregnant teenagers, there are particular themes based upon wants and needs. Some of the wants expressed by teens includes, "(a) the desire to be or be perceived as more grown up, with increased responsibility, independence and maturity; (b) a long history of desiring pregnancy and the maternal role; c) never having had anything to call their own and wanting something to care for and love and (d) the pregnancy was the natural next step in their life or their relationship with their boyfriend." In the same study, it was concluded that no one should assume that a teenage pregnancy was an accident or unwanted as some have been proven to be planned.

Reality television shows and teen pregnancy

Reality television shows featuring teen pregnancy have become increasingly popular over the last few decades. MTV's 16 and Pregnant was very popular between the years of 2009-2014. The show featured a different teenage mother each episode and documented most of their pregnancy and a short period after birth. The show and network saw success and went on to produce multiple spin off series including: Teen Mom, Teen Mom 2, Teen Mom 3, Teen Mom: Young and Pregnant.

TLC has also engaged in producing this type of content with their television series Unexpected.

The results of a study performed for the Journal of Health Communication,[36] suggest that young women who watched shows such as 16 and Pregnant did report a lower perception of their own risk for pregnancy. The girls also reported predicting the behaviors and intentions that result in teenage pregnancy.

See also

References

- ↑ "An Analysis of Out-Of-Wedlock Births in the United States". The Brookings Institution. August 1, 1996. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- 1 2 "About Teen Pregnancy | CDC". www.cdc.gov. November 15, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ↑ "ONDCP: Hispanic teens more likely than whites, blacks to use drugs". PsycEXTRA Dataset. 2007. doi:10.1037/e426482008-009. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- 1 2 DeParle, Jason (December 31, 2022). "Their Mothers Were Teenagers. They Didn't Want That for Themselves". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- 1 2 Wildsmith, Elizabeth; Welti, Kate; Finocharo, Jane; Ryberg, Renee; Manlove, Jennifer (December 23, 2022). "Teen Births Have Declined by More Than Three Quarters Since 1991 - Child Trends". Child Trends. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Unintended Pregnancy Prevention | Unintended Pregnancy | Reproductive Health | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "The Office of Adolescent Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services". Office of Adolescent Health. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ↑ Witt WP, Wiess AJ, Elixhauser A (December 2014). "Overview of Hospital Stays for Children in the United States, 2012". HCUP Statistical Brief #186. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. PMID 25695124.

- 1 2 3 4 "About Teen Pregnancy | Teen Pregnancy | Reproductive Health | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "www.guttmacher.org" (PDF). Guttmacher Institute. June 2013. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ↑ Chen, X.-K.; Wen, S. W.; Fleming, N.; Demissie, K.; Rhoads, G. G.; Walker, M. (April 1, 2007). "Teenage pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: a large population based retrospective cohort study". International Journal of Epidemiology. 36 (2): 368–373. doi:10.1093/ije/dyl284. ISSN 0300-5771. PMID 17213208.

- ↑ "Data". thenationalcampaign.org. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ↑ Timothy W. Martin (2011). "Birth Rate Continues to Slide Among Teens". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "11 Facts About Teen Pregnancy | DoSomething.org | Volunteer for Social Change". www.dosomething.org. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- 1 2 "Policy Brief: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Teen Pregnancy" (PDF). The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. July 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2008. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ↑ Burrus, Barri B. (February 1, 2018). "Decline in Adolescent Pregnancy in the United States: A Success Not Shared by All". American Journal of Public Health. 108 (S1): S5–S6. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304273. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 5813784. PMID 29443563.

- ↑ Vazsonyi, Alexander T.; Chen, Pan; Young, Maureen; Jenkins, Dusty; Browder, Sara; Kahumoku, Emily; Pagava, Karaman; Phagava, Helen; Jeannin, Andre; Michaud, Pierre-Andre (December 1, 2008). "A Test of Jessor's Problem Behavior Theory in a Eurasian and a Western European Developmental Context". Journal of Adolescent Health. 43 (6): 555–564. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.013. ISSN 1054-139X. PMID 19027643.

- ↑ Kost, Kathryn; Henshaw, Stanley (2014), U.S. Teenage Pregnancies, Births and Abortions, 2010:National and State Trends by Age, Race and Ethnicity (PDF), retrieved June 8, 2015

- 1 2 3 4 "Teenage Births: Outcomes for Young Parents and Their Children" (PDF). December 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 10, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Furstenberg, Frank (November 1, 2016). "Reconsidering Teenage Pregnancy and Parenthood". Societies. 6 (4): 33. doi:10.3390/soc6040033.

- 1 2 3 "Statistics on Teenage Pregnancy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 18, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ↑ Myers, Wendy S. "Babies Having Babies. (Cover Story)." Women In Business 42.4 (1990): 18-20. Academic Search Complete. Web. 25 Oct. 2016.

- ↑ Martinez, D. (February 7, 2009). "Teen Parenting Program aims to keep young mothers in school". Valley Morning Star. Archived from the original on December 3, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

Saenz said the program, which follows a TEA curriculum, reaches out to girls and boys from middle school to high school who are facing a pregnancy to educate them about the parenting process, resources, federal programs and continuing their education.

- ↑ Sadler L. S., Swartz M. K., Ryan-Krause P., Seitz V., Meadows-Oliver M., Grey M., Clemmens D. A. (2007). "Promising Outcomes in Teen Mothers Enrolled in a School-Based Parent Support Program and Child Care Center". Journal of School Health. 77 (3): 121–130. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00181.x. PMID 17302854.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Van Pelt, Jennifer (March–April 2012). "Keep Teen Mom's In School- A School Social Work". Social Work Today. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ↑ Stanger-Hall, Kathrin F.; Hall, David W. (October 14, 2011). "Abstinence-Only Education and Teen Pregnancy Rates: Why We Need Comprehensive Sex Education in the U.S". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e24658. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...624658S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024658. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3194801. PMID 22022362.

- ↑ Trussell, James (Spring 2017). "Teenage Pregnancy in the United States". Family Planning Perspectives. 6 (6): 262–272. doi:10.2307/2135482. JSTOR 2135482.

- ↑ Santelli, John S.; Lindberg, Laura Duberstein; Finer, Lawrence B.; Singh, Susheela (January 2007). "Explaining Recent Declines in Adolescent Pregnancy in the United States: The Contribution of Abstinence and Improved Contraceptive Use". American Journal of Public Health. 97 (1): 150–156. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.089169. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 1716232. PMID 17138906.

- ↑ Live births by age of mother and sex of child bred, general and age-specific fertility rates: latest available year, 2000–2009 — United Nations Statistics Division – Demographic and Social Statistics

- 1 2 Darroch, Jacqueline; Singh, Susheela; Frost, Jennifer (February 9, 2005). "Differences in Teenage Pregnancy Rates Among Five Developed Countries: The Roles of Sexual Activity and Contraceptive Use".

- ↑ "Sex and HIV Education". March 14, 2016.

- ↑ Darroch, Jacqueline; Singh, Susheela; Frost, Jennifer (February 9, 2005). "Differences in Teenage Pregnancy Rates Among Five Developed Countries: The Roles of Sexual Activity and Contraceptive Use". Guttmacher Institute.

- 1 2 Boonstra, Heather. "What Is Behind the Declines in Teen Pregnancy Rates?". Guttmacher Institute. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ↑ Patten, Eileen; Gretchen Livingston (April 29, 2016). "Why is the teen birth rate falling?". Pew Research Center. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- ↑ Montgomery, Kristen S. (November 1, 2002). "Planned adolescent pregnancy: What they wanted". Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 16 (6): 282–289. doi:10.1067/mph.2002.122083. ISSN 0891-5245. PMID 12436097.

- ↑ Aubrey, Jennifer Stevens; Behm-Morawitz, Elizabeth; Kim, Kyungbo (October 3, 2014). "Understanding the Effects of MTV's 16 and Pregnant on Adolescent Girls' Beliefs, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intentions Toward Teen Pregnancy". Journal of Health Communication. 19 (10): 1145–1160. doi:10.1080/10810730.2013.872721. ISSN 1081-0730. PMID 24628488. S2CID 12327917.

Further reading

- Ventura, Stephanie J., Brady E. Hamilton, and T. J. Mathews. (2013). "Pregnancy and childbirth among females aged 10–19 years—United States, 2007-2010". CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report—United States, 2013. Vol. 62. pp. 71–76.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)