37°34′08″N 126°58′36″E / 37.56889°N 126.97667°E

| Third Battle of Seoul | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Korean War | |||||||

Chinese troops celebrate the capture of Seoul. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ~170,000[8] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

China: ~5,800 North Korea: ~2,700[12] | ||||||

The Third Battle of Seoul was a battle of the Korean War, which took place from December 31, 1950, to January 7, 1951, around the South Korean capital of Seoul. It is also known as the Chinese New Year's Offensive, the January–Fourth Retreat (Korean: 1•4 후퇴) or the Third Phase Campaign Western Sector[nb 4] (Chinese: 第三次战役西线; pinyin: Dì Sān Cì Zhàn Yì Xī Xiàn).

In the aftermath of the major Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) victory at the Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River, the United Nations Command (UN) started to contemplate the possibility of evacuation from the Korean Peninsula. Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong ordered the Chinese People's Volunteer Army to cross the 38th Parallel in an effort to pressure the UN forces to withdraw from South Korea.

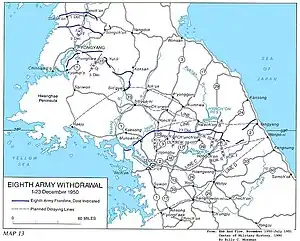

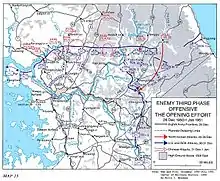

On December 31, 1950, the Chinese 13th Army attacked the Republic of Korea Army (ROK)'s 1st, 2nd, 5th and 6th Infantry Divisions along the 38th Parallel, breaching UN defenses at the Imjin River, Hantan River, Gapyeong and Chuncheon in the process. To prevent the PVA forces from overwhelming the defenders, the US Eighth Army now under the command of Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway evacuated Seoul on January 3, 1951.

Although PVA forces captured Seoul by the end of the battle, the Chinese invasion of South Korea galvanized the UN support for South Korea, while the idea of evacuation was soon abandoned by the UN Command. At the same time, the PVA were exhausted after months of nonstop fighting since the start of the Chinese intervention, thereby allowing the UN forces to regain the initiative in Korea. The city would change hands one more time in Operation Ripper.

Background

With China entering the Korean War in late 1950, the conflict had entered a new phase.[13] To prevent North Korea from falling under UN control after the UN offensive into North Korea,[14] the PVA entered North Korea and launched their Second Phase Offensive against the UN forces near the Sino-Korean border on 25 November.[15] The resulting battles at the Ch'ongch'on River Valley and the Chosin Reservoir forced the UN forces to retreat from North Korea during December 1950, with PVA and North Korean Korean People's Army (KPA) forces recapturing much of North Korea.[16] On the Korean western front, after the US Eighth Army suffered a disastrous defeat at the Ch'ongch'on River, it retreated back to the Imjin River while setting up defensive positions around the South Korean capital of Seoul.[16] Although the Eighth Army was ordered to hold Seoul for as long as possible,[17] UN commander General Douglas MacArthur planned a series of withdrawals to the Pusan Perimeter if UN forces were about to be overwhelmed.[16] General Walton Walker, commander of the Eighth Army, was killed in a traffic accident on December 23, and Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway assumed command of the Eighth Army on December 26, 1950.[18] At the UN, a ceasefire along the 38th Parallel was proposed to China on December 11, 1950, in order to avoid any further escalation of hostility between the US and China.[19]

Although the PVA had been weakened from their earlier battles, with nearly 40 percent of its forces rendered combat ineffective,[20] its unexpected victories over the UN forces had convinced the Chinese leadership of the invincibility of the PVA.[21] Immediately after the PVA 13th Army's victory over the Eighth Army at the Ch'ongch'on River, Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong started to contemplate another offensive against the UN forces on the urging of North Korean Premier Kim Il Sung.[22] After learning of MacArthur's plans and the UN ceasefire, Mao also believed that the UN evacuation of the Korean Peninsula was imminent.[23] Although the over-stretched Chinese logistics prevented the PVA from launching a full-scale invasion against South Korea,[24] Mao still ordered the PVA 13th Army to launch an intrusion, dubbed the "Third Phase Campaign", to hasten the UN withdrawal and to demonstrate China's desire for a total victory in Korea.[25] On December 23, 1950, China's Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai formally rejected the UN ceasefire while demanding all UN forces to be withdrawn from the Korean Peninsula.[26]

Prelude

Locations, terrain, and weather

Seoul is the capital city of South Korea. Korea as a whole is roughly bisected into northern and southern halves by the Han River. Seoul is located 35 mi (56 km) south of the 38th Parallel.[27] The battle was fought over the UN defenses at the 38th Parallel, which stretches horizontally from the Imjin River mouth on the Korean west coast to the town of Chuncheon in central Korea.[28] Route 33 runs south across the 38th Parallel at the Hantan River, passes through Uijeongbu and eventually arrives at Seoul, and it is an ancient invasion route towards Seoul.[7] Another road ran across the Imjin River, and it connects Seoul and Kaesong through the towns of Munsan and Koyang.[29] Finally, a road runs through Chuncheon and it connects to Seoul from the northeast.[30] The harsh Korean winter, with temperatures as low as −20 °C (−4 °F),[31] had frozen the Imjin and the Hantan River over most of the river crossings, eliminating a major obstacle for the attacking Chinese forces.[32][33]

Forces and strategies

| "[UN evacuation of Korea] will prove to be true soon or at least when our 13th Army Corps reaches Kaesong or Seoul." |

| Mao Zedong arguing for the new offensive[23] |

By December 22, 1950, the US Eighth Army's front had stabilized along the 38th Parallel.[34] Just days before his death, Walker placed US I Corps, US IX Corps, and ROK III Corps of the Eighth Army along the 38th Parallel to defend Seoul.[34] US I and IX Corps were to defend the Imjin and Hantan River respectively,[34] while ROK III Corps were to guard the areas around Chuncheon.[34] The boundary between US I and IX Corps was marked by Route 33, and was defended by the ROK 1st Infantry Division on the west side and the ROK 6th Infantry Division on the east side.[35]

Because the ROK forces had suffered nearly 45,000 casualties at the end of 1950,[36] most of their units were composed of raw recruits with little combat training.[37] After inspecting the front just days before the battle, General J. Lawton Collins, the US Army Chief of Staff, concluded that most of the ROK formations were only fit for outpost duties.[38] At the same time, the Eighth Army was also suffering from low morale due to its earlier defeats,[39] and most of its soldiers were anticipating an evacuation from Korea.[40] The Eighth Army's lack of will to fight and to maintain contact with Chinese forces resulted in a lack of information on PVA troop movements and intentions.[41] After inspecting the front on December 27, Ridgway ordered US I and IX Corps to organize a new defensive line around Koyang to Uijeongbu, called the Bridgehead Line, to cover the Han River crossings in case the UN forces were forced to evacuate Seoul.[42]

The PVA, however, were also suffering from logistics problems and exhaustion after their earlier victories.[43] Arguing against the Third Phase Campaign on December 7, PVA Commander Peng Dehuai telegraphed to Mao that the PVA would need at least three months to replace its casualties, while most of its troops were in critical need of resupply, rest and reorganization.[43] The Chinese logistics system, which was based on the concept of People's War with the native population supplying the army, also ran into difficulties due to the indifferent and sometimes hostile, Korean population near the 38th Parallel.[44] The PVA were now suffering from hunger and the lack of winter clothing.[45]

Responding to Peng's concern over the troops' conditions, Mao limited the scope of the Third Phase Campaign to pin down the ROK forces along the 38th Parallel while inflicting as much damage as possible.[46] Upon noticing that the US units were not interspersed between the ROK formations, therefore unable to support them,[47] Mao ordered the PVA 13th Army to destroy the ROK 1st Infantry Division, the ROK 6th Infantry Division and ROK III Corps.[46] Following Mao's instruction, Peng placed the PVA 38th, 39th, 40th and 50th Corps of the 13th Army in front of the ROK 1st and 6th Infantry Divisions, while the 42nd and the 66th Corps of the 13th Army were moved into ROK III Corps' sector.[46] The start date of the offensive was set to 31 December in order to take advantage of the night assault under a full moon and the anticipated low alertness of the UN soldiers during the holiday.[46] For the same reasons Ridgway had predicted that 31 December would be the likely time for the new Chinese offensive.[28] Believing that the destruction of the ROK forces at the 38th Parallel would render the UN forces incapable of counterattacks in the future, Mao promised to pull all Chinese troops off the front line for rest and refit by the end of the campaign.[46]

Battle

On the evening of December 31, 1950, the PVA 13th Army launched a massive attack against the ROK forces along the 38th Parallel. Along the Imjin River and the Hantan River, the PVA 38th, 39th, 40th and 50th Corps decimated the ROK 1st Division while routing the ROK 6th Division.[48] At the Chuncheon sector, the PVA 42nd and the 66th Corps forced ROK III Corps into full retreat.[49] With the defenses at the 38th Parallel completely collapsed by January 1, 1951,[50] Ridgway ordered the evacuation of Seoul on January 3.[51]

Actions at the Imjin River and the Hantan River

By December 15, 1950, the ROK 1st Infantry Division had retreated back to the town of Choksong on the southern bank of the Imjin River, its original defensive position at the start of the Korean War.[52][53] On the right flank of the ROK 1st Infantry Division, the ROK 6th Infantry Division was located at the north of Dongducheon along the southern bank of the Hantan River.[54] The ROK 1st Infantry Division planned to defend the Imjin River by placing its 11th and 12th Regiments at the west and the east side of Choksong respectively,[52] while the ROK 6th Infantry Division defended the Route 33 at the Hantan River by placing its 7th and 19th Regiments on each side of the road.[54] Both the ROK 15th Regiment, 1st Infantry Division and the ROK 2nd Regiment, 6th Infantry Division were placed in the rear as reserves.[52][54] The South Koreans had also constructed numerous bunkers, barbed wire obstacles and minefields on both banks of the river in order to strengthen defenses and to maintain troop morale.[55]

Faced with the South Korean defense, the Chinese had prepared for well over a month for the offensive.[8] In the weeks before the operational orders for the Third Phase Campaign were issued by PVA High Command, the advance elements of the PVA 39th Corps had been conducting detailed reconnaissance on the ROK defenses.[8] The ROK positions were then thoroughly analyzed by PVA commanders, engineers and artillery officers.[56] PVA "thrust" companies, which were composed of specially trained assault and engineer teams, were also organized to lead the attack across the Imjin and Hantan River.[57] During the preparation, the PVA artillery units had suffered heavy losses under UN air attacks, but PVA Deputy Commander Han Xianchu still managed to bring up 100 artillery pieces against the ROK fortifications.[31] On December 22, the PVA High Command issued the operational orders that signaled the start of the Third Phase Campaign.[46] The PVA 39th and 50th Corps were tasked with the destruction of the ROK 1st Infantry Division, while the 38th and the 40th Corps were tasked with the destruction of the ROK 6th Infantry Division.[58]

Acting on Ridgway's prediction, the ROK Army Headquarters ordered all units to full alert at dusk on December 31,[59] but many of its soldiers were either drunk from the New Year celebration or had abandoned their posts in order to escape the cold.[60][61] The PVA artillery units began to shell the ROK defenses at 16:30 on December 31.[62] The first blow fell on the ROK 12th Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, due to the unit's positioning as both the boundary between the ROK 1st and 6th Infantry Divisions and the boundary between US I and IX Corps.[63][64] Because the river banks on ROK 12th Regiment's flanks were composed of high cliffs difficult for the attackers to scale, most of the regiment's strength were used to defend its center.[65] Upon noticing this development, the PVA 39th Corps decided to use ROK 12th Regiment's flanks as the main points of attack in order to achieve maximum surprise.[65] Following a feint attack on the ROK 12th Regiment's center, the PVA 116th and 117th Divisions of the 38th Corps struck both flanks of the ROK 12th Regiment.[63] The ROK 12th Regiment was caught off guard and offered little resistance, and within hours the regiment was cut to pieces with a battery of the US 9th Field Artillery Battalion seized by the Chinese.[66] Under the cover of the fleeing ROK soldiers, the attacking PVA forces then penetrated the ROK 15th Regiment's defense without firing a shot.[67] Desperate to contain the PVA breakthrough, Brigadier General Paik Sun Yup of the ROK 1st Infantry Division used the division's rear service personnel to form an assault battalion, but they were unable to stop the PVA advance.[64][67] With only the ROK 11th Regiment remaining intact by the morning of January 1, the ROK 1st Infantry Division was forced to withdraw on January 2.[68]

| "Only few miles north of Seoul, I ran head-on into that fleeing army. I'd never had such an experience before, and I pray to God I never witness such a spectacle again." |

| Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway after meeting the ROK 6th Infantry Division[69] |

The PVA attacks against the ROK 6th Infantry Division, however, did not go as commanders had planned.[48] The original plan called for the PVA 38th and the 40th Corps to attack the ROK 19th Regiment, 6th Infantry Division's right flank,[70] but the bulk of the PVA forces mistakenly attacked the US 19th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division, which was stationed to the east of the ROK 19th Regiment.[48] The poor intelligence had also made the PVA charge through several minefields, resulting in heavy casualties.[48] In spite of the losses, the PVA pushed the US 19th Infantry Regiment back, exposing the right flank of the ROK 6th Infantry Division in the process.[48][71] With the ROK 1st Infantry Division out of action and the US 24th Infantry Division's defenses penetrated, the PVA forces on both flanks of the ROK 6th Infantry Division then advanced southward in an attempt to encircle the division.[71] By midnight of the New Year's Eve, the ROK 6th Infantry Division was forced into full retreat.[48] Although the PVA managed to intercept some elements of the ROK 6th Infantry Division, most of the ROK escaped the trap by infiltrating the PVA lines using the mountain trails.[72] As Ridgway tried to inspect the front on the morning of January 1, he was greeted by the fleeing and weaponless remnants of the ROK 6th Infantry Division a few miles north of Seoul.[69] Despite Ridgway's efforts to stop the retreat, the division continued to flee south.[69] It was not until the personal intervention of South Korean President Syngman Rhee that the division finally stopped its retreat.[73] By the night of January 1, the UN defenses at the Imjin River and the Hantan River had completely collapsed with the PVA advancing 9 mi (14 km) into UN territory.[74] The Chinese stopped their advance on January 2.[75]

Actions at Gapyeong and Chuncheon

At the beginning of the battle ROK III Corps was located to the east of the US 24th Infantry Division of US IX Corps, defending the 38th Parallel to the north of Gapyeong (Kapyong) and Chuncheon.[76] Composed of four divisions, ROK III Corps placed its 2nd Infantry Division on the Corps' left flank at the hills north of Gapyeong, while the 5th Infantry Division defended the Corps' center at Chuncheon.[76] The cold winter created great difficulties for the ROK defenders, with the heavy snow hindering construction and icy roads limiting food and ammunition supplies.[76] North Korean guerrillas were also active in the region, and had caused serious disruption in the rear of ROK III Corps.[76]

The Chinese operational order for the Third Phase Campaign called for the 42nd and the 66th Corps to protect the PVA left flank by eliminating the ROK 2nd and 5th Infantry Divisions,[77] while cutting the road between Chuncheon and Seoul.[46] Following instructions, the two PVA Corps quickly struck after midnight on New Year's Eve.[78] The PVA 124th Division first penetrated the flanks of the ROK 2nd Infantry Division, then blocked the division's retreat route.[78][79] The trapped ROK 17th and 32nd Regiments, 2nd Infantry Division were forced to retreat in disarray.[78] With the PVA 66th Corps pressuring the ROK 5th Infantry Division's front, the PVA 124th Division then advanced eastward in the rear and blocked the ROK 5th Infantry Division's retreat route as well.[79] The maneuver soon left the ROK 36th Regiment, 5th Infantry Division surrounded by PVA and they had to escape by infiltrating the PVA lines using mountain trails.[80] By January 1, ROK III Corps had lost contact with the 2nd and 5th Infantry Divisions, while the rest of the III Corps were retreating to the town of Wonju.[49] On January 5, the PVA 42nd and 66th Corps were relieved by the KPA II and V Corps,[81] and the KPA launched a separate offensive towards Wonju.[75][82]

Evacuation of Seoul

In the aftermath of the PVA attacks on along the 38th Parallel, Ridgway worried that the Chinese would exploit the breakthrough at Chuncheon to circle the entire Eighth Army.[51] He also lacked confidence in the UN troops' ability to hold against the Chinese offensive.[51] On the morning of January 3, after conferring with Major General Frank W. Milburn and Major General John B. Coulter, commanders of the US I and IX Corps, respectively, Ridgway ordered the evacuation of Seoul.[83] With the collapse of the UN defenses at the 38th Parallel, the retreat had already started on January 1.[84] At 09:00 on January 1, Milburn ordered US I Corps to retreat to the Bridgehead Line.[75] Following his orders, the US 25th Infantry Division of I Corps took up position to the west of Koyang, while the British 29th Independent Infantry Brigade of I Corps had dug in to the east.[84][85] To the east of I Corps, Coulter also ordered the withdrawal of US IX Corps at 14:00 with the Anglo-Australian 27th British Commonwealth Brigade covering the rear.[86][87] Some PVA forces managed to trap the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR) of the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade at Uijeongbu during their attacks against the ROK 6th Infantry Division, but the battalion escaped the trap with four wounded.[87] By midnight on January 1, the US 24th Infantry Division of the IX Corps reached the Bridgehead Line south of Uijeongbu,[88] and the 27th Commonwealth Brigade was moved into the IX Corps rear as reserves.[87]

The PVA forces lacked the ability to lay siege to Seoul, so the evacuation order caught Peng by surprise.[89] On the morning of January 3, Peng ordered the PVA 13th Army to pursue the retreating UN forces by attacking towards Seoul.[90] The US 24th, 25th Infantry Division and the British 29th Infantry Brigade soon bore the brunt of the PVA attacks.[91] In US IX Corps' sector, PVA 38th Corps attacked the US 24th Infantry Division as the American were trying to withdraw.[92] In the fierce fighting that followed, the US 19th Infantry Regiment on the division's left flank was involved in numerous hand-to-hand struggles with the PVA around Uijeongbu.[3] The PVA overran Companies E and G of US 19th Infantry Regiment during their attacks, but US artillery and air strikes soon inflicted 700 casualties in return.[92] Faced with the heavy PVA pressure, the 27th Commonwealth Brigade was again called in to cover the retreat of US IX Corps.[93] After the US 24th Division evacuated Seoul on the night of January 3, the 27th Commonwealth Brigade started to cross the Han River on the morning of January 4,[94] and by 07:40 the entire US IX Corps had left Seoul.[95]

| "At last after weeks of frustration we have nothing between us and the Chinese. I have no intention that this Brigade Group will retire before the enemy unless ordered by higher authority in order to conform with general movement. If you meet him you are to knock hell out of him with everything you got. You are only to give ground on my orders." |

| Brigadier Thomas Brodie's order to the 29th Independent Infantry Brigade during the defense of Seoul[96] |

On the left flank of the US 24th Infantry Division, the British 29th Infantry Brigade of US I Corps was involved in the hardest fighting of the entire battle.[97] In the 29th Infantry Brigade's first action of the Korean War, the brigade was ordered to defend the areas east of Koyang on the Bridgehead Line.[98] The 1st Battalion, Royal Ulster Rifles (1RUR) covered the brigade's left flank, while the 1st Battalion, Royal Northumberland Fusiliers (1RNF) was stationed on the brigade's right flank.[96] The 1st Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment and the 1st Battalion, 21st Royal Thai Regiment covered the brigade's rear with artillery support.[96][99] At 04:00 on January 3, 1RUR first made contact with the 149th Division of the PVA 50th Corps.[100] The PVA surprised and overran the Companies B and D of 1RUR, but a counterattack by Major C. A. H. B. Blake of 1RUR restored the battalion's position by the morning.[100] While 1RUR was under attack, the PVA forces also infiltrated 1RNF's positions by exploiting the unguarded valleys between hilltops occupied by the British.[100] The entire 1RNF soon came under sniper fire and the PVA made repeated attempts to capture Y Company of 1RNF.[101] To restore 1RNF's position, Brigadier Thomas Brodie of the 29th Infantry Brigade sent W Company of 1RNF with four Churchill tanks as reinforcement.[101] The reinforcement was met with machine gun and mortar fire, but the PVA resistance immediately crumbled under the Churchill tanks' devastating assaults.[101] The surviving PVA troops fled under the bombardment from 4.2-inch mortars and 25 pounder field guns.[102] In the aftermath of fighting, the 29th Infantry Brigade suffered at least 16 dead, 45 wounded and 3 missing,[102] while 200 PVA dead were found within 1RNF's position.[103]

While the British 29th Infantry Brigade and the PVA 149th Division fought at the east of Koyang, the US 25th Infantry Division of US I Corps started to withdraw on the left flank of 29th Infantry Brigade.[104] The evacuation plan called for a coordinated withdrawal between the US 25th Infantry Division and the British 29th Infantry Brigade in order to prevent the PVA from infiltrating the UN rear areas, but the heavy fighting soon made the coordination between American and British units impossible.[105] After the US 27th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division formed the rearguard of US I Corps, the 25th Infantry Division and the 29th Infantry Brigade were ordered to evacuate at 15:00 on January 3.[97] The 25th Infantry Division retreated with little difficulties,[106] but the withdrawal of the 29th Infantry Brigade did not start until after dark at 21:30.[102] With the road completely open between the US rearguards and the British units,[103] the PVA 446th Regiment, 149th Division infiltrated UN rear areas and set up an ambush against 1RUR and the Cooper Force of the 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars.[91][107][nb 5] 1RUR and the Cooper Force were then quickly overrun by Chinese soldiers, most of whom were completely unarmed.[108] The PVA had also attacked the Cromwell tanks of the Cooper Force with bundle grenades and Bangalore torpedoes, setting several on fire.[91][107] In the desperate hand on hand fighting that followed, although 100 soldiers from 1RUR managed to escape the trap under the command of Major J.K.H. Shaw, Major Blake of 1RUR and Captain D. Astley-Cooper of the Cooper Force were killed in action,[109] while another 208 British soldiers were missing in action, most of whom were captured by the PVA.[107][110] The US 27th Infantry Regiment tried to rescue the trapped British troops, but Brodie stopped the rescue in order to prevent more unnecessary losses.[111][112]

When the British 29th Infantry Brigade left Seoul at 08:00 on January 4,[111] the US 27th Infantry Regiment became the last UN tactical unit that remained in the city.[113] After fighting several more holding engagements at the outskirts of Seoul, the 27th Infantry Regiment crossed the Han River at 14:00 on January 4.[114]

Ridgway warned his forces around noon on the 4th to expect orders to withdraw to Line D, all Corps abreast. I and IX Corps in the meantime were to pull back at 20:00 to intermediate positions 6–8 miles (9.7–12.9 km) south of the Han and hold until Air Force and Army supplies stocked at Suwon, 10 miles (16 km) farther south, had been removed. Ridgway expected the supplies to be cleared within 24 to 36 hours. Ridgway intended that the starting hour of the intermediate move provide time for the 3rd Logistical Command to finish evacuating Inchon, ASCOM City and Kimpo airfield. On 3 January Ridgway had notified Col. John G. Hill, commander of the 3rd Logistical Command, to cease port operations at Inchon at noon the next day. The deadline seemed reasonable since the gradual reductions of stocks at the port and airfield areas since early December already had brought items on hand to modest quantities. But unforeseen delays in getting some reserve stocks released from Eighth Army staff officers, too few tankers, too little suitable shipping for such items as long lengths of railroad track, and an overestimate of the ammunition that would be issued to line troops had prevented Colonel Hill from removing all stocks by the designated hour. After receiving Ridgway's noontime orders, General Milburn, in whose sector the port and airfield lay, instructed Hill to execute his demolition plans as soon as he had removed all troops other than demolition crews. While back shipment at Inchon did continue through the favorable afternoon tide on the 4th, Hill's main attention was diverted to rendering the airfield and port facilities useless to PVA/KPA forces. All port units scheduled to travel south by road had gone by the time Hill received Milburn's instructions, and the last Fifth Air Force unit except for Army aviation engineers had flown from Kimpo to a new base in Japan. Through the afternoon these engineers burned the airfield buildings and the drums of aviation gasoline and napalm remaining at Kimpo while Eighth Army engineers from the 82nd Engineer Petroleum Distribution Company destroyed the four- and six-inch pipelines between Inchon and Kimpo and the booster pumps and storage tanks at the airfield. Members of the 50th Engineer Port Construction Company began demolishing the Inchon port at 18:00. All main facilities except one pier and a causeway to the island of Wolmi-do, were destroyed. Prime targets were the lock gates of the tidal basin, which by compensating the Yellow Sea's wide tidal range had largely given Inchon the capacity of a principal port. The demolitions at Wolmi-do as well as the city itself were completed by 03:00 on the 5th. Colonel Hill and his remaining troops left by water for Pusan within the hour. Supplies destroyed at Kimpo, ASCOM City and Inchon included some 1.6 million gallons of petroleum products, 9,300 tons of engineer materiel, and 12 rail cars loaded with ammunition. While time and tide may have made the destruction of this materiel unavoidable, the extensive damage to port facilities could not be fully justified. Denying the enemy the use of a port was theoretically sound; on the other hand, the UN Command's absolute control of Korean waters made Inchon's destruction purposeless.[115]

On the afternoon of January 4, the KPA I Corps, the PVA 38th Corps and the PVA 50th Corps entered Seoul, but they were only greeted by an empty city in flames.[116] Most of the civilians had either fled south through the frozen Han River or evacuated to the nearby countryside.[117] The South Korean government in Seoul, which was reduced to essential personnel before the battle, also left the city with little difficulties.[118] A KPA platoon reached the Seoul City Hall at about 13:00 and raised the North Korean flag.[119] On January 5, Peng ordered the PVA 50th Corps and the KPA I Corps to seize Gimpo and Incheon while instructing all other units to rest on the northern bank of the Han River.[116] By January 7, Peng halted the Third Phase Campaign due to troop exhaustion and to prevent a repeat of the Incheon landing.[12]

Eighth Army withdrawal to Line D

I and IX Corps left the lower bank of the Han while Hill's engineers were still blowing Inchon, so Hill had been obliged to put out his own security above the port. These outposts were not engaged. Neither were Milburn's forces as they moved to positions centered on Route 1 at the town of Anyang, nor were Coulter's as they extended the intermediate line northeastward to the junction of the Han and Pukhan rivers. Late on the 4th, while I and IX Corps were withdrawing to positions above Suwon, Ridgway ordered the withdrawal to Line D to begin at noon on the 5th, by which time he now expected the supplies at Suwon to have been removed. All five Corps were to withdraw abreast, meeting in the process Ridgway's basic requirement of maximum delay and maximum punishment of the enemy. Ridgway specifically instructed Milburn and Coulter to include tanks in their covering forces and to counterattack the PVA who followed the withdrawal. Ridgway learned during the morning of the 5th that the supplies at Suwon and at the airfield south of town could not be cleared by noon. Creating the delay was not only the sheer bulk of the materiel but also about 100,000 desperate refugees from the Seoul area who crowded the Suwon railroad yards and blocked the trains. At mid-morning Ridgway radioed Milburn to stand fast until the remaining Suwon stocks had been shipped out and he notified Coulter to leave forces to protect the east flank of I Corps' forward position. Milburn received Ridgway's instructions in time to hold the bulk of the 25th Division and the ROK 1st Division at the Anyang position and Coulter ordered the ROK 6th Division to protect Milburn's east flank. But Coulter did not dispatch his instructions until an hour after the ROK 6th had started for Line D, and General Chang did not receive them until midafternoon. It took Chang another half-hour to get his division stopped. By that time his forces were almost due east of Suwon, where, with Coulter's agreement, Chang deployed them along Route 17.[120]

During the night of the 5th a PVA regiment crossed the Han and assembled east of Yongdungp'o. Patrols from the regiment moved south through the hills east of Route 1 and reconnoitered the ROK 1st Division front before midnight but somehow missed finding the vulnerable east flank earlier left open by IX Corps. By daylight on the 6th the patrol contact in the center of General Paik's front developed into a general engagement between a PVA battalion and the ROK 3rd Battalion, 11th Regiment, but the PVA attempt to dislodge the ROK eased by noon and ended altogether at 14:00. By then supplies had been cleared from Suwon and Milburn and Coulter could continue south toward Line D. The two Corps completed their withdrawals on the 7th. Since the 15th Infantry and 3rd Battalion, 65th Infantry, of the 3rd Division in the meantime had arrived from Kyongju and been attached to I Corps, Milburn was able to keep a substantial reserve and still organize a fairly solid 20 miles (32 km) Line D front from the west coast eastward through Pyongtaek and Ansong. The British 29th Brigade and the Thai battalion stood at the far left astride Route 1 just below P’yongt’aek. The 3rd Division held a sector across the hills between Routes 1 and 17, which General Soule manned with the 15th Infantry. Lending depth to this central position, the 3rd Battalion, 65th Infantry, and the 35th Infantry of the 25th Division were assembled not far behind it. Above Ansong, the ROK 1st Division lay across Route 17. The remainder of the 25th Division and the Turkish Brigade went into Corps' reserve at Cheonan, 13 miles (21 km) south of Pyongtaek. Along a slightly longer front tipping to the northeast and reaching beyond Changhowon-ni to the Han River, Coulter deployed the ROK 6th Division, British 27th Brigade, and 24th Division, west to east. Hard against the right Corps' boundary 20 miles (32 km) behind the front, the bulk of the 1st Cavalry Division was in Corps' reserve at Ch’ungju on Route 13, now IX Corps’ main supply route. To protect the route from attacks by guerrillas known to be located in the Tanyang area 20 miles (32 km) further east, the 5th Cavalry Regiment had begun to patrol the road from Ch’ungju south through a mountain pass at Mun’gyong.[121]

The way Milburn and Coulter had moved to Line D exasperated General Ridgway. "Reports so far reaching me," he told the two Corps commanders on the 7th, "indicate your forces withdrew to ‘D’ line without evidence of having inflicted any substantial losses on enemy and without material delay. In fact, some major units are reported as having broken contact. I desire prompt confirming reports and if substantially correct, the reasons for non-compliance with my basic directives." The reports reaching Ridgway were true. Except for the clashes between the PVA and the ROK 1st Division east of Anyang on the 6th, I Corps had withdrawn from the south bank of the Han without contact and IX Corps had not engaged enemy forces since leaving the Bridgehead Line. Attempting once more to get the quality of leadership he considered essential, Ridgway pointed out to Milburn and Coulter that their opponents had only two alternatives: to make a time-consuming, coordinated follow-up, or to conduct a rapid, uncoordinated pursuit. If the PVA chose the first, Eighth Army could at least achieve maximum delay even though there might be few opportunities for strong counterattacks. If they elected the second, Eighth Army would have unlimited opportunities not only to delay but to inflict severe losses on them. In either case, Ridgway again made clear, Milburn and Coulter were to exploit every opportunity to carry out the basic concept of operations that he had repeatedly explained to them. The immediate response was a flurry of patrolling to regain contact. According to the I Corps intelligence officer, the 39th and 50th Armies were now advancing south of Seoul, and their vanguards had reached the Suwon area. An ROK 1st Division patrol moving north over Route 17 during the afternoon of the 7th supported this assessment when it briefly engaged a small PVA group in Kumnyangjang-ni, 11 miles (18 km) east of Suwon. Further west, patrols from the 15th Infantry and the British 29th Brigade moved north as far as Osan, 8 miles (13 km) short of Suwon, without making contact. In the IX Corps' sector, the 24th Division at the far right sent patrols into Icheon and Yeoju, both on an east–west line with Suwon. Both towns were empty. Shallower searches to the north by the British 27th Brigade in the center of the Corps' sector also failed to reestablish contact. General Ridgway considered the attempts by patrols to regain contact at least to be moves in the right direction. What he wanted and planned to see next in the west was more vigorous patrolling by gradually enlarged forces. This patrolling would be the main mission of the larger efforts to acquire better combat intelligence, which in his judgment had been sadly neglected and which was a prime requisite for the still larger offensive action that he intended would follow. His attention meanwhile was drawn to the east, where the withdrawal to Line D was still in progress and where KPA forces, as expected, had opened an attack to seize Wonju.[122]

Aftermath

| "Now that [they] celebrate the recovery of Seoul, what would they have to say if the military situation requires us to evacuate Seoul in the future?" |

| PVA Deputy Commander Deng Hua reflecting on the victory[123] |

Although UN casualties were moderate,[123][124][nb 6] the Third Battle of Seoul was a significant success for the Chinese military, and the UN forces' morale sunk to its lowest point during the war.[125] Ridgway was also extremely displeased with the performance of Eighth Army[126] and took immediate steps to restore the morale and fighting spirit of the UN forces.[127][128] With Ridgway leading the Eighth Army, MacArthur started to regain confidence in UN forces' ability to hold Korea, and the UN evacuation plan was abandoned on January 17.[129]

Meanwhile, at the UN, although the US and other UN members were initially divided on how to respond to Chinese intervention,[130] the Chinese rejection of the UN ceasefire soon rallied the UN members towards the US,[131] and a UN resolution that condemned China as an aggressor was passed on February 1.[131] In the opinion of historian Bevin Alexander, the Chinese rejection of a UN ceasefire had damaged the international prestige it had obtained from its earlier military successes, and this later made it difficult for China to either join the UN or to oppose US support for Taiwan.[26] The Korean War, which ultimately ended at the 38th Parallel, would drag on for another two bloody years due to the determination of Communist China and the North Korean leadership to establish communism on the entire Korean Peninsula.[26]

Despite its victory, the PVA had become exhausted after nonstop fighting.[132] PVA Deputy Commander Han Xianchu later reported to Peng that, although combat casualties had been light with only 8,500 battle casualties,[12] poor logistics and the exhaustion had cost the "backbone" of the Chinese forces during the Third Phase Campaign.[116] US Far East Air Forces' "Interdiction Campaign No.4 ", which was launched on December 15, 1950, against PVA/KPA supply lines, also made the PVA unable to sustain any further offensives southward.[133] Believing that the UN forces were thoroughly demoralized and unable to counterattack, Mao finally permitted the PVA to rest for at least two to three months, while Peng and other Chinese commanders were planning for a decisive battle in the spring of 1951.[134] The CPV party committee issued orders regarding tasks during rest and reorganization on 8 January, outlining Chinese war goals. The orders read: "the central issue is for the whole party and army to overcome difficulties ... to improve tactics and skills. When the next campaign starts ... we will annihilate all enemies and liberate all Korea." In his telegram to Peng on 14 January, Mao stressed the importance of preparing for "the last battle" in the spring in order to "fundamentally resolve the [Korean] issue".[135]

To the surprise of Chinese commanders, Ridgway and the Eighth Army soon counterattacked the PVA with Operation Thunderbolt on January 25, 1951.[136][137]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ In Chinese military nomenclature, the term "Army" (军) means Corps, while the term "Army Group" (集团军) means Army.

- ↑ KATUSA number not included. See Appleman 1990, p. 40.

- ↑ This is the total casualty number of the US 24th and 25th Division from January 1 to January 15, 1951. See Ecker 2005, p. 74.

- ↑ The Eastern Sector is the First and Second Battles of Wonju.

- ↑ Cooper Force was an ad hoc unit composed of the reconnaissance troops and six Cromwell tanks from the 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars. See Farrar-Hockley 1990, p. 386.

- ↑ The extent of the South Korean losses is unknown due to the lack of records. See Appleman 1989, p. 403.

Citations

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 302.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 242.

- 1 2 Appleman 1990, p. 63.

- ↑ Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs 2010, p. 119.

- ↑ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 369.

- ↑ Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs 2010, p. 72.

- 1 2 Appleman 1990, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1990, p. 42.

- ↑ Ecker 2005, p. 74.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 71.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 2001, p. 262.

- 1 2 3 Zhang 1995, p. 132.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. xvi.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, p. 120.

- ↑ Millett, Allan R. (2009). "Korean War". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Mossman 1990, p. 160.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 159.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 390, 397.

- ↑ Alexander 1986, pp. 371–375.

- ↑ Roe 2000, p. 412.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, pp. 119, 121.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, p. 121.

- 1 2 Zhang 1995, p. 124.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, pp. 125, 126.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, p. 126.

- 1 2 3 Alexander 1986, p. 376.

- ↑ Daily 1996, p. 41.

- 1 2 Mossman 1990, p. 180.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 60.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 188.

- 1 2 Zhang 1995, p. 130.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 353.

- ↑ "Third Battle Of Seoul – Korean War". WorldAtlas. Retrieved 2017-07-21.

- 1 2 3 4 Mossman 1990, p. 161.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Millett 2010, p. 372.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 368–369.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 370.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 34.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 382.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 183.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 186.

- 1 2 Zhang 1995, p. 123.

- ↑ Shrader 1995, pp. 174–175.

- ↑ Shrader 1995, p. 174.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Zhang 1995, p. 127.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Appleman 1990, p. 50.

- 1 2 Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 386–387.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 189.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1990, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 352.

- ↑ Paik 1992, p. 112.

- 1 2 3 Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 357.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 352–353.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 45.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 348–349.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 351.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Paik 1992, p. 117.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 46.

- 1 2 Appleman 1990, p. 49.

- 1 2 Paik 1992, p. 115.

- 1 2 Appleman 1990, p. 47.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, pp. 49, 51.

- 1 2 Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 354.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 355.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1990, p. 51.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 349.

- 1 2 Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 358.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 358–359.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 52.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, pp. 54, 55.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1990, p. 55.

- 1 2 3 4 Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 360.

- ↑ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 174.

- 1 2 3 Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 361.

- 1 2 Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 180.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 361–362.

- ↑ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, pp. 187–188.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 219.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 59.

- 1 2 Mossman 1990, p. 192.

- ↑ Farrar-Hockley 1990, p. 387.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 194.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1990, p. 53.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 195.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, pp. 125, 131.

- ↑ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, pp. 183–184.

- 1 2 3 Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 183.

- 1 2 Appleman 1990, p. 62.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 64.

- ↑ Farrar-Hockley 1990, p. 394.

- 1 2 3 Farrar-Hockley 1990, p. 386.

- 1 2 Appleman 1990, p. 66.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 54.

- ↑ Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs 2010, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1990, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 Farrar-Hockley 1990, p. 389.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1990, p. 68.

- 1 2 Farrar-Hockley 1990, p. 390.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 65.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, pp. 68–69.

- 1 2 3 Farrar-Hockley 1990, p. 391.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Cunningham 2000, p. 4.

- 1 2 Appleman 1990, p. 73.

- ↑ Farrar-Hockley 1990, p. 392.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 80.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, pp. 210–212.

- 1 2 3 Zhang 1995, p. 131.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 377.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 376–377.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 79.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, pp. 212–213.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, pp. 213–215.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, pp. 215–216.

- 1 2 Zhang 1995, p. 133.

- ↑ Ecker 2005, p. 73.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 83.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 91.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, pp. 234–236.

- ↑ Appleman 1990, p. 145.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 236.

- ↑ Alexander 1986, pp. 370–371.

- 1 2 Alexander 1986, p. 388.

- ↑ Ryan, Finkelstein & McDevitt 2003, p. 131.

- ↑ Shrader 1995, pp. 175–176.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Zhihua, Shen, and Yafeng Xia. "Mao Zedong's Erroneous Decision During the Korean War: China's Rejection of the UN Cease-fire Resolution in Early 1951". Asian Perspective 35, no. 2 (2011): 187–209.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, p. 136.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 242.

References

- Alexander, Bevin R. (1986), Korea: The First War We Lost, New York: Hippocrene Books, Inc, ISBN 978-0-87052-135-5

- Appleman, Roy (1989), Disaster in Korea: The Chinese Confront MacArthur, vol. 11, College Station, Texas: Texas A and M University Military History Series, ISBN 978-1-60344-128-5

- Appleman, Roy (1990), Ridgway Duels for Korea, vol. 18, College Station, Texas: Texas A and M University Military History Series, ISBN 0-89096-432-7

- Chae, Han Kook; Chung, Suk Kyun; Yang, Yong Cho (2001), Yang, Hee Wan; Lim, Won Hyok; Sims, Thomas Lee; Sims, Laura Marie; Kim, Chong Gu; Millett, Allan R. (eds.), The Korean War, vol. II, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-7795-3

- Chinese Military Science Academy (2000), History of War to Resist America and Aid Korea (抗美援朝战争史) (in Chinese), vol. II, Beijing: Chinese Military Science Academy Publishing House, ISBN 7-80137-390-1

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (2001), The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles, St Leonards: Allen and Unwin, ISBN 1-86508-634-7

- Cunningham, Cyril (2000), No Mercy, No Leniency: Communist Mistreatment of British Prisoners of War in Korea, Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Leo Cooper, ISBN 0-85052-767-8

- Daily, Edward L. (1996), We Remember: U.S. Cavalry Association, Nashville, Tennessee: Turner Publishing Company, ISBN 978-1-56311-318-5

- Ecker, Richard E. (2005), Korean Battle Chronology: Unit-by-Unit United States Casualty Figures and Medal of Honor Citations, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, ISBN 0-7864-1980-6

- Farrar-Hockley, Anthony (1990), Official History: The British Part in the Korean War, vol. I, London, England: HMSO, ISBN 0-11-630953-9

- Millett, Allan R. (2010), The War for Korea, 1950-1951: They Came From the North, Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, ISBN 978-0-7006-1709-8

- Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs (2010), The Eternal Partnership: Thailand and Korea - A History of the Participation of the Thai Forces in the Korean War (PDF), Sejong City, South Korea: Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs, archived from the original (PDF) on August 26, 2014, retrieved 2014-08-22

- Mossman, Billy C. (1990), Ebb and Flow: November 1950 – July 1951, United States Army in the Korean War, Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, ISBN 978-1-4102-2470-5, archived from the original on January 29, 2021, retrieved July 4, 2010

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Paik, Sun Yup (1992), From Pusan to Panmunjom, Riverside, New Jersey: Brassey Inc, ISBN 0-02-881002-3

- Roe, Patrick C. (2000), The Dragon Strikes, Novato, CA: Presidio, ISBN 0-89141-703-6

- Ryan, Mark A.; Finkelstein, David M.; McDevitt, Michael A. (2003), Chinese Warfighting: The PLA Experience Since 1949, Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 0-7656-1087-6

- Shrader, Charles R. (1995), Communist Logistics in the Korean War, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-29509-3

- Zhang, Shu Guang (1995), Mao's Military Romanticism: China and the Korean War, 1950–1953, Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, ISBN 0-7006-0723-4

Further reading

- Spurr, Russell (1988). Enter the Dragon: China's Undeclared War Against the U.S. in Korea 1950–51. New York: Newmarket Press. ISBN 1-55704-008-7.