| Timelines of World War II |

|---|

| Chronological |

| Prelude |

| By topic |

The Manhattan Project was a research and development project that produced the first atomic bombs during World War II. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army Corps of Engineers. The Army component of the project was designated the Manhattan District; "Manhattan" gradually became the codename for the entire project. Along the way, the project absorbed its earlier British counterpart, Tube Alloys. The Manhattan Project began modestly in 1939, but grew to employ more than 130,000 people and cost nearly US$2 billion (about $34.2 billion in 2022[1] dollars). Over 90% of the cost was for building factories and producing the fissionable materials, with less than 10% for development and production of the weapons.[2][3]

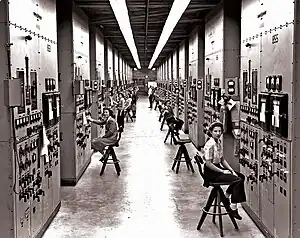

Two types of atomic bombs were developed during the war. A relatively simple gun-type fission weapon was made using uranium-235, an isotope that makes up only 0.7 percent of natural uranium. Since it is chemically identical to the most common isotope, uranium-238, and has almost the same mass, it proved difficult to separate. Three methods were employed for uranium enrichment: electromagnetic, gaseous and thermal. Most of this work was performed at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. In parallel with the work on uranium was an effort to produce plutonium. Reactors were constructed at Oak Ridge and Hanford, Washington, in which uranium was irradiated and transmuted into plutonium. The plutonium was then chemically separated from the uranium. The gun-type design proved impractical to use with plutonium so a more complex implosion-type nuclear weapon was developed in a concerted design and construction effort at the project's principal research and design laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico.

The following is a timeline of the Manhattan Project. It includes a number of events prior to the official formation of the Manhattan Project, and a number of events after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, until the Manhattan Project was formally replaced by the Atomic Energy Commission in 1947.

.jpg.webp)

1939

- August 2: Albert Einstein signs the letter (Einstein–Szilárd letter), authored by physicist Leó Szilárd and addressed to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, advising him to fund research into the possibility of using nuclear fission as a weapon as Nazi Germany may also be conducting such research.[6]

- September 3: Great Britain and France declare war on Nazi Germany in response to its invasion of Poland, beginning World War II.[7]

- October 11: Economist Alexander Sachs meets with President Roosevelt and delivers the Einstein–Szilárd letter. Roosevelt authorizes the creation of the Advisory Committee on Uranium.[8]

- October 21: First meeting of the Advisory Committee on Uranium, headed by Lyman Briggs of the National Bureau of Standards; $6,000 is budgeted for neutron experiments.[9]

1940

- March 2: John R. Dunning's team at Columbia University verifies Niels Bohr's hypothesis that uranium 235 is responsible for fission by slow neutrons.[10]

- March: University of Birmingham-based scientists Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls author the Frisch–Peierls memorandum, calculate that an atomic bomb might need as little as 1 pound (0.45 kg) of enriched uranium to work. The memorandum is given to Mark Oliphant, who in turn hands it over to Sir Henry Tizard.[11]

- April 10: MAUD Committee established by Tizard to investigate feasibility of an atomic bomb.[12]

- May 21: George Kistiakowsky suggests using gaseous diffusion as a means of isotope separation.[13]

- June 12: Roosevelt creates the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) under Vannevar Bush, which absorbs the Uranium Committee.[14]

- September 6: Bush tells Briggs that the NDRC will provide $40,000 for the uranium project.[15]

- September – Belgian mining engineer Edgar Sengier orders that half of the uranium stock available from the Shinkolobwe mine in the Belgian Congo—about 1,050 tons—be secretly dispatched to New York by African Metals Corp., a commercial division of Union Minière.[16][17]

1941

- February 25: Conclusive discovery of plutonium by Glenn Seaborg and Arthur Wahl at the University of California, Berkeley.[18]

- May 17: A report by Arthur Compton and the National Academy of Sciences is issued which finds favorable the prospects of developing nuclear power production for military use.[19]

- June 28: Roosevelt creates the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) under Vannevar Bush with the signing of Executive Order 8807.[20] OSRD absorbs NDRC and the Uranium Committee. James B. Conant succeeds Bush as the head of NDRC.[21]

- July 2: The MAUD Committee chooses James Chadwick to write the second (and final) draft of its report on the design and costs of developing a bomb.[22]

- July 15: The MAUD Committee issues final detailed technical report on design and costs to develop a bomb. Advance copy sent to Vannevar Bush who decides to wait for official version before taking any action.[23]

- August: Mark Oliphant travels to USA to urge development of a bomb rather than power production.[24]

- 30 August 1941: Winston Churchill becomes the first national leader to approve a nuclear weapons programme: the project was named Tube Alloys

- September 3: British Chiefs of Staff Committee approve Tube Alloys.[25]

- October 3: Official copy of MAUD Report (written by Chadwick) reaches Bush.[24]

- October 9: Bush takes MAUD Report to Roosevelt, who approves Project to confirm MAUD's findings. Roosevelt asks Bush to draft a letter so that the British government could be approached "at the top."[26]

- December 6: Bush holds a meeting to organize an accelerated research project, still managed by Arthur Compton. Harold Urey is assigned to develop research into gaseous diffusion as a uranium enrichment method, while Ernest O. Lawrence is assigned to investigate electromagnetic separation methods which resulted in the invention of Calutron.[27][28] Compton puts the case for plutonium before Bush and Conant.[29]

- December 7: The Japanese attack Pearl Harbor. The United States and Great Britain issue a formal declaration of war against Japan the next day.[30]

- December 11: The same day after Germany and Italy declare war on the United States, the United States declares war on Germany and Italy.[31]

- December 18: First meeting of the OSRD sponsored S-1 Section, dedicated to developing nuclear weapons.[32]

1942

- January 19: Roosevelt formally authorizes the atomic bomb project.[33]

- January 24: Compton decides to centralize plutonium work at the University of Chicago.[34]

- June 19: S-1 Executive Committee is formed, consisting of Bush, Conant, Compton, Lawrence and Urey.[35]

- June 25: S-1 Executive Committee selects Stone & Webster as primary contractor for construction at the Tennessee site.[36]

- July–September: Physicist Robert Oppenheimer convenes a summer conference at the University of California, Berkeley to discuss the design of a fission bomb. Edward Teller brings up the possibility of a hydrogen bomb as a major point of discussion.[37]

- July 30: Sir John Anderson urges Prime Minister Winston Churchill to pursue a joint project with the United States.[38]

- August 13: The Manhattan Engineering District with James C. Marshall as District Engineer is established by the Chief of the United States Army Corps of Engineers, Major General Eugene Reybold, effective August 16.[39]

- September 17: Major General Wilhelm D. Styer and Reybold order Colonel Leslie Groves to take over the project.[40]

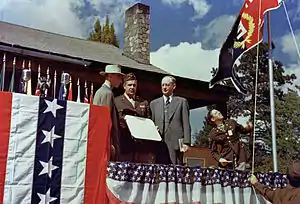

- September 23: Groves is promoted to brigadier general, and becomes director of the project. The Military Policy Committee, consisting of Bush (with Conant as his alternative), Styer and Rear Admiral William R. Purnell is created to oversee the project.[41]

- September - Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Nichols meets Edgar Sengier in the New York offices of Union Minière. Nichols has been ordered by General Groves to find uranium. Sengier's answer has become history: "You can have the ore now. It is in New York, a thousand tons of it. I was waiting for your visit." Nichols reaches an agreement with Sengier that an average of 400 tons of uranium oxide will begin shipping to the US from Shinkolobwe each month.[42]

- September 26: The Manhattan Project is given permission to use the highest wartime priority rating by the War Production Board.[43]

- September 29: Under Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson authorizes the Corps of Engineers to acquire 56,000 acres (23,000 ha) in Tennessee for Site X, which will become the Oak Ridge, Tennessee, laboratory and production site.[44]

- October - 100 tons of Sengier's uranium ore is sent to Canada for refining by Eldorado Mining and Refining in Port Hope, Ontario.[42]

- October - A special detachment from United States Army Corps of Engineers arrives in the Belgian Congo to reopen the Shinkolobwe mine in the Belgian Congo. Work involves draining water from flooded workings, upgrading the plant machinery and constructing transportation facilities.[16]: 3, 6–7, 11

- October 15: after a meeting in Chicago on the Manhattan Project General Leslie Groves invited J. Robert Oppenheimer to join himself, James C. Marshall and Kenneth Nichols on their return trip to New York on the 20th Century Limited. After dinner on the train they discussed the project while squeezed into Nichol’s one-person roomette (of about 40" by 80" or 1m by 2m). Shortly afterwards Oppenheimer was appointed to head the Los Alamos Laboratory (Site Y).[45][46]

- October 19: Groves appoints Oppenheimer to coordinate the scientific research of the project at the Site Y laboratory.[47]

- November - The first uranium oxide shipment leaves the Congolese port of Lobito (it will later change to Matadi because of better security). Only two shipments will ever be lost at sea. Aerodromes at Elizabethville and Leopoldville are expanded with US assistance. The OSS is employed to prevent ore smuggling to Nazi Germany.[16]: 3, 6–7, 11 [17]: 45–49

- November 16: Groves and Oppenheimer visit Los Alamos, New Mexico and designate it as the location for Site Y.[48]

- December 2: Chicago Pile-1, the first nuclear reactor goes critical at the University of Chicago under the leadership and design of Enrico Fermi, achieving a self-sustaining reaction just one month after construction was started.[49]

1943

- January 16: Groves approves development of the Hanford Site.[50]

- February 9: Patterson approves acquisition of 400,000 acres (160,000 ha) at Hanford.[50]

- February 18: Construction begins for Y-12, a massive electromagnetic separation plant for enriching uranium at Oak Ridge.[51]

- April 1: Los Alamos laboratory is established.[52]

- April 5–14: Robert Serber delivers introductory lectures at Los Alamos, later are compiled into The Los Alamos Primer.[53]

- April 20: The University of California becomes the formal business manager of the Los Alamos laboratory.[54]

- Mid-1943: The S-1 Committee was eliminated by mid-1943, as it had been superseded by the Military Policy Committee.[55]

- June 2: Construction begins of K-25, the gaseous diffusion plant.[56]

- July: The president proclaims Los Alamos, Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) and Hanford Engineer Works (HEW) as military districts. The Governor of Tennessee Prentice Cooper was officially handed the proclamation making Oak Ridge a military district not subject to state control by a junior officer (a lieutenant) he tore it up and refused to see the MED District Engineer Lt-Col James C. Marshall. The new District Engineer Kenneth Nichols had to placate him.[57][58]

- July 10: First sample of plutonium arrives at Los Alamos.[59]

- August 10: Medical Section of the MED created, on 3 November Colonel Stafford Warren commissioned to head it.[60]

- August 13: First drop test of gun-type fission weapon at Dahlgren Proving Ground under the direction of Norman F. Ramsey.[61]

- August 13: Kenneth Nichols replaces Marshall as head of the Manhattan Engineer District.[62] One of his first tasks as district engineer is to move the district headquarters to Oak Ridge, although its name did not change.[52]

- August 19: Roosevelt and Churchill sign Quebec Agreement. Tube Alloys is merged with the Manhattan project.[63]

- September 8: First meeting of the Combined Policy Committee, established by the Quebec Agreement to coordinate the efforts of the United States, United Kingdom and Canada. United States Secretary of War Henry Stimson, Bush and Conant are the American members; Field Marshal Sir John Dill and Colonel J. J. Llewellin are the British members, and C. D. Howe is the Canadian member.[64]

- October 10: Construction begins for the first reactor at the Hanford Site.[65]

- November 4: X-10 Graphite Reactor goes critical at Oak Ridge.[66]

- December 3: The British Mission, 15 scientists including Rudolf Peierls, Franz Simon and Klaus Fuchs, arrives at Newport News, Virginia.[67]

1944

- January 11: A special group of the Theoretical Division is created at Los Alamos under Edward Teller to study implosion.[68]

- March 11: Beta calutrons commence operation at Oak Ridge.[69]

- April 5: At Los Alamos, Emilio Segrè receives the first sample of reactor-bred plutonium from Oak Ridge, and within ten days discovers that the spontaneous fission rate is too high for use in a gun-type fission weapon (because of Pu-240 isotope present as an impurity in the Pu-239).[70]

- May 9: The world's third reactor, LOPO, the first aqueous homogeneous reactor, and the first fueled by enriched uranium, goes critical at Los Alamos.[71]

- July 4: Oppenheimer reveals Segrè's final measurements to the Los Alamos staff, and the development of the gun-type plutonium weapon[72]

- July 17: "Thin Man" is abandoned. Designing a workable implosion design (Fat Man) becomes the top priority of the laboratory, and design of the uranium gun-type weapon (Little Boy) continued.[73]

- July 20: The Los Alamos organizational structure is completely changed to reflect the new priority.[74]

- September 2: Two chemists are killed, and Arnold Kramish almost killed, after being sprayed with highly corrosive hydrofluoric acid while attempting to unclog a uranium enrichment device which is part of the pilot thermal diffusion plant at the Philadelphia Navy Yard.[75]

- September 22: First RaLa test with a radioactive source performed at Los Alamos.[76]

- September 26: The largest nuclear reactor, the B reactor, goes critical at the Hanford Site.[77]

- Late November: Samuel Goudsmit, scientific head of the Alsos Mission, concludes, based on papers recovered in Strasbourg, that the Germans did not make substantial progress towards an atomic bomb or nuclear reactor, and that the programs were not even considered high priority.[78]

- December 14: Definite evidence of achievable compression obtained in a RaLa test.[79]

- December 17: 509th Composite Group formed under Colonel Paul W. Tibbets to deliver the bomb.[80]

1945

- January: Brigadier General Thomas Farrell is named Groves' deputy.[81]

- January 7: First RaLa test using exploding-bridgewire detonators.[79]

- January 20: First stages of K-25 are charged with uranium hexafluoride gas.[82]

- February 2: First Hanford plutonium arrives at Los Alamos.[83]

- April 22: Alsos Mission captures German experimental nuclear reactor at Haigerloch.[84]

- April 27: First meeting of the Target Committee.[85]

- May 7: Nazi Germany formally surrenders to Allied powers, marking the end of World War II in Europe;[86] 100-ton test explosion at Alamogordo, New Mexico.[79]

- May 10: Second meeting of the Target Committee, at Los Alamos.[87]

- May 28: Third meeting which works to finalize the list of cities on which atomic bombs may be dropped: Kokura, Hiroshima, Niigata and Kyoto.[87]

- May 30: Stimson drops Kyoto from the target list; it is replaced by Nagasaki.[87]

- June 11: Metallurgical Laboratory scientists under James Franck issue the Franck Report arguing for a demonstration of the bomb before using it against civilian targets.[88]

- July 16: the first nuclear explosion, the Trinity nuclear test of an implosion-style plutonium-based nuclear weapon known as the gadget at Alamogordo;[89] USS Indianapolis sails for Tinian with Little Boy components on board.[90]

- July 19: Oppenheimer recommends to Groves that gun-type design be abandoned and the uranium-235 used to make composite cores (but Little Boy was not abandoned).[91]

- July 24: President Harry S. Truman discloses to Soviet leader Joseph Stalin that the United States has atomic weapons. Stalin feigns little surprise; he already knows this through espionage.[92]

- July 25: General Carl Spaatz is ordered to bomb one of the targets: Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata or Nagasaki as soon as weather permitted, some time after August 3.[93]

- July 26: Potsdam Declaration is issued, threatening Japan with "prompt and utter destruction".[94]

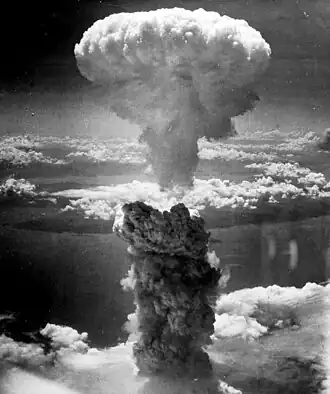

- August 6: B-29 Enola Gay drops Little Boy, a gun-type uranium-235 weapon, on the city of Hiroshima, the primary target.[95]

- August 9: B-29 Bockscar drops a Fat Man implosion-type plutonium weapon on the city of Nagasaki, the secondary target, as the primary, Kokura, is obscured by cloud and smoke.[96]

- August 12: The Smyth Report is released to the public, giving the first technical history of the development of the first atomic bombs.[97]

- August 13: Groves holds shipment of material for a third bomb, on his own authority as he could not reach Marshall or Stimson; as it would be a terrible mistake for us to send overseas the ingredients of another atomic bomb.[98] A Fat Man bomb as enough U-235 for a second Little Boy bomb would not be available until December.[99]

- August 14: Surrender of Japan to the Allied powers.[100]

- August 21: Harry Daghlian, a physicist, receives a fatal dose (510 rems) of radiation from a criticality accident when he accidentally dropped a tungsten carbide brick onto a plutonium bomb core. He dies on September 15.[101]

- September 4: Manhattan District orders shutdown of S-50 liquid thermal diffusion plant and the Y-12 Alpha plant.[102]

- September 8: Manhattan Project survey group under Farrell arrives in Nagasaki.[103]

- September 17: Survey group under Colonel Stafford L. Warren arrives in Nagasaki.[103]

- September 22: Last Y-12 alpha track ceases operating.[102]

- October 16: Oppenheimer resigns as director of Los Alamos, and is succeeded by Norris Bradbury the next day.[104]

1946

- February: News of the Russian spy ring in Canada exposed by defector Igor Gouzenko is made public, creating a mild "atomic spy" hysteria, pushing American Congressional discussions about postwar atomic regulation in a more conservative direction.[105]

- May 21: Physicist Louis Slotin receives a fatal dose of radiation (2100 rems) when the screwdriver he was using to keep two beryllium hemispheres apart slips.[106]

- July 1: Able test at Bikini Atoll as part of Operation Crossroads.[107]

- July 25: Underwater Baker test at Bikini.[107]

- August 1: Truman signs the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 into law, ending almost a year of uncertainty about the control of atomic research in the postwar United States.[108]

1947

- January 1: the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (known as the McMahon Act) takes effect, and the Manhattan Project is officially turned over to the United States Atomic Energy Commission.[109]

- August 15: Manhattan District is abolished.[110]

See also

Notes

- ↑ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ↑ Nichols 1987, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ "Atomic Bomb Seen as Cheap at Price". Edmonton Journal. 7 August 1945. p. 1. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ↑ "The Calutron Girls". SmithDRay. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ↑ Beck, Alfred M, et al., United States Army in World War II: The Technical Services – The Corps of Engineers: The War Against Germany, 1985 Chapter 24, "Into the Heart of Germany", p. 558

- ↑ Rhodes 1986, p. 307.

- ↑ Rhodes 1986, p. 310.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 17.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 20.

- ↑ Rhodes 1986, p. 332.

- ↑ Gowing 1964, pp. 40–43.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 18.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 31.

- ↑ Zachary 1997, p. 112.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Williams, Susan (2016). Spies in the Congo. New York: Public Affairs. pp. 186–187. ISBN 9781610396547.

- 1 2 Zoellner, Tom (2009). Uranium. London: Penguin Books. p. 45. ISBN 9780143116721.

- ↑ Rhodes 1986, pp. 383–384.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 37.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. (June 28, 1941). "Executive Order 8807 Establishing the Office of Scientific Research and Development". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved June 28, 2011.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 41.

- ↑ Gowing 1964, p. 76.

- ↑ Rhodes 1986, pp. 368–369.

- 1 2 Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Gowing 1964, p. 106.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 44–46.

- ↑ Yergey, Alfred L.; Yergey, A. Karl (1997-09-01). "Preparative Scale Mass Spectrometry: A Brief History of the Calutron". Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 8 (9): 943–953. doi:10.1016/S1044-0305(97)00123-2. ISSN 1044-0305. S2CID 95235848.

- ↑ "Lawrence and His Laboratory: Episode: The Calutron". www2.lbl.gov. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- ↑ Rhodes 1986, pp. 388–389.

- ↑ Williams 1960, p. 3.

- ↑ Williams 1960, p. 4.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 53.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 49.

- ↑ Rhodes 1986, p. 399.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 75.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 126.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 42–47.

- ↑ Gowing 1964, pp. 437–438.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 43.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 75.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 77.

- 1 2 Nichols 1987, p. 45.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 81.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 78.

- ↑ Nichols 1987, pp. 73.

- ↑ Bird & Sherwin 2005, p. 186.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 83.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 84.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 112.

- 1 2 Jones 1985, p. 110.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 152.

- 1 2 Jones 1985, p. 88.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 69.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 66.

- ↑ Nichols 1987, p. 115.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 130.

- ↑ Groves 1962, pp. 26, 27.

- ↑ Nichols 1987, p. 99,100.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 79.

- ↑ Nichols 1987, pp. 122, 123.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 380.

- ↑ Nichols 1987, p. 101.

- ↑ Gowing 1964, p. 171.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 241.

- ↑ Rhodes 1986, p. 499.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 211.

- ↑ Rhodes 1995, p. 103.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 157.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 164.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 238.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 202.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 240.

- ↑ Hoddeson, Lillian (1993). "The Discovery of Spontaneous Fission in Plutonium during World War II". Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences. 23 (2): 279–300. doi:10.2307/27757700. ISSN 0890-9997. JSTOR 27757700.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 245.

- ↑ "Explosion at Navy Yard". Manhattan Project Heritage Preservation Association. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 269.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 221.

- ↑ Goudsmit 1947, pp. 69–79.

- 1 2 3 Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 271.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 521.

- ↑ Nichols 1987, p. 171.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 300.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 310.

- ↑ Rhodes 1986, p. 609.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 528.

- ↑ Williams 1960, p. 534.

- 1 2 3 Jones 1985, p. 529.

- ↑ Jones 1985, pp. 532–533.

- ↑ Williams 1960, p. 550.

- ↑ Rhodes 1986, p. 670.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 377.

- ↑ Rhodes 1986, p. 690.

- ↑ Rhodes 1986, p. 691.

- ↑ Rhodes 1986, p. 692.

- ↑ Jones 1985, pp. 536–538.

- ↑ Jones 1985, pp. 538–541.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 561.

- ↑ Groves 1962, p. 352.

- ↑ Nichols 1987, p. 175.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 405–406.

- ↑ McLaughlin, Thomas P.; Monahan, Shean P.; Pruvost, Norman L.; Frolov, Vladimir V.; Ryazanov, Boris G.; Sviridov, Victor I. (May 2000). "A Review of Criticality Accidents" (PDF). Los Alamos, New Mexico: Los Alamos National Laboratory. pp. 74–75. LA-13638. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- 1 2 Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 624.

- 1 2 Jones 1985, p. 544.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 401.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 480–481.

- ↑ Zeilig, Martin (August–September 1995). "Louis Slotin And 'The Invisible Killer'". The Beaver. 75 (4): 20–27. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- 1 2 Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 580–581.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 596.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 641.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 600.

References

- Bird, Kai; Sherwin, Martin J. (2005). American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41202-8.

- Goudsmit, Samuel A. (1947). Alsos. New York: Henry Schuman. ISBN 0-938228-09-9. OCLC 8805725.

- Gowing, Margaret (1964). Britain and Atomic Energy, 1935–1945. London: Macmillan Publishing. OCLC 3195209.

- Groves, Leslie (1962). Now It Can Be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project. New York: Harper. ISBN 0-306-70738-1. OCLC 537684.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Anderson, Oscar E. (1962). The New World, 1939–1946 (PDF). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-07186-7. OCLC 637004643. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Hoddeson, Lillian; Henriksen, Paul W.; Meade, Roger A.; Westfall, Catherine L. (1993). Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943–1945. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44132-3. OCLC 26764320.

- Jones, Vincent (1985). Manhattan: The Army and the Atomic Bomb. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 10913875.

- Nichols, Kenneth D. (1987). The Road to Trinity. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-06910-X. OCLC 15223648.

- Rhodes, Richard (1986). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-44133-7. OCLC 13793436.

- — (1995). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80400-X.

- Williams, Mary H. (1960). Chronology 1941–1945. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army.

- Zachary, G. Pascal (1997). Endless Frontier: Vannevar Bush, Engineer of the American Century. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 0-684-82821-9. OCLC 36521020.

External links

- AtomicArchive.com: Manhattan Project Chronology Archived 2008-10-30 at the Wayback Machine – from "The Manhattan Project: Making the Atomic Bomb" by DOE−Department of Energy.

- NuclearWeaponArchive.org: Chronology for the origin of atomic weapons